Abstract

OBJECTIVE—To identify clinical and serological differences of patients with reactive arthritis after infection with Lancefield group A β-haemolytic streptococci (GAS), compared with non-group A—that is, group C or G streptococci (NGAS:GCS/GGS), and a group of culture negative or unidentified streptococci (GUS). METHODS—A prospective study of consecutive patients with reactive arthritis after serologically or culture confirmed infection with β-haemolytic streptococci, presenting to the outpatient department of rheumatology from January 1992 until January 1998. Alternative causes for reactive arthritis were excluded. Main outcome measures were clinical and serological characteristics including antistreptolysine-O (ASO) and antideoxyribonuclease-B (antiDNase-B) antibody titres. RESULTS—41 patients (female/male ratio 22/19; mean (SD) age 38 (13) years) with reactive arthritis were included. Culture of throat swab was positive in 13 cases (32%): 6 (15%) GAS, 7 NGAS (17%), that is, 5 (12%) GCS, 2 (5%) GGS. In 28 cases throat culture remained negative resulting in a group of unidentified streptococci; antibiotic pre-treatment had been given by the general practitioner in 18 cases (64%). Arthritis was non-migratory, the number of arthritic joints in GAS and NGAS was similar, whereas in NGAS patients fewer joints were involved than in GUS: mean (SEM) 36 swollen joint index: 3.3 (1.0) in NGAS v 5.6 (1.0) in GUS (p<0.005); 28 swollen joint index: 2.9 (1.0) in NGAS v 4.3 (0.8) in GUS (p<0.05). Extra-articular manifestations—that is, erythema nodosum/ multiforme, AV conduction block or hepatitis—were observed after GAS or GUS infection, but not after NGAS infection. ASO and/or antiDNase-B rose significantly in all patients. The maximal titres for ASO and antiDNase-B in 41 PSRA patients were: mean (SEM) 1242 (232) U/l and 890 (100) U/l respectively; the maximal ASO titres were similar in the three groups: mean (SEM) 1125 (185) in GAS, 625 (160) in NGAS (GAS v NGAS: p=0.17), and 1430 (320) U/l in GUS (NGAS v GUS: p=0.10). AntiDNase-B titres were: mean (SEM) 1075 (180) in GAS, 375 (105) in NGAS (GAS v NGAS: p<0.01), and 995 (125) U/l in GUS (NGAS v GUS: p<0.005). ASO: antiDNase-B ratios were: mean (SEM) 0.89 (0.21) in GAS, 2.60 (0.76) in NGAS (GAS v NGAS: p<0.05), and 1.43 (0.28) in GUS (NGAS v GUS: p=0.12). CONCLUSION—Post-streptococcal reactive arthritis occurs not infrequently. Differentiation of PSRA based on the causative streptococcal strain is frequently thwarted by negative throat cultures. Sometimes extra-articular manifestations are present that exclude NGAS as the causative organism. Serologically, lower antiDNase-B titres may be indicative for primary NGAS infection; the ASO/antiDNase-B ratio may be of additive value for differentiation in cases of a negative throat culture: the higher ASO/antiDNase-B ratios suggesting primary NGAS infection. In reactive arthritis, serological monitoring consisting of a simultaneous titration of antiDNase-B and ASO, seems to be of clinical importance to trace GAS induced cases, especially when throat cultures remain negative.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (81.9 KB).

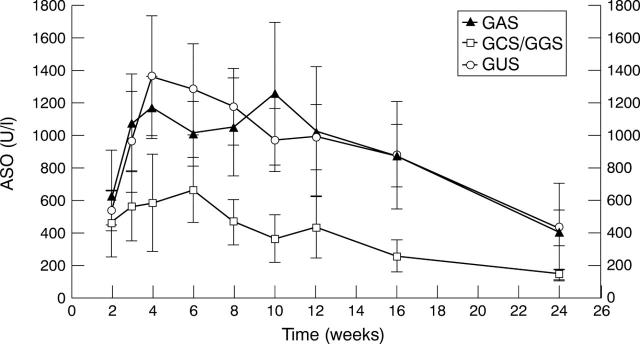

Figure 1 .

Antibody titres of ASO in the GAS (n=6), NGAS (n=7), and GUS induced (n=28) PSRA patients from week 2-24 after streptococcal throat infection. Data are means (SEM).

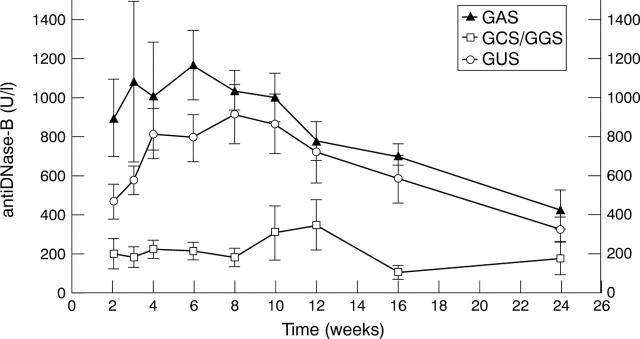

Figure 2 .

Antibody titres of antiDNase-B in the GAS- (n=6), NGAS (n=7), and GUS induced (n=28) PSRA patients from week 2-24 after streptococcal throat infection. Data are means (SEM).

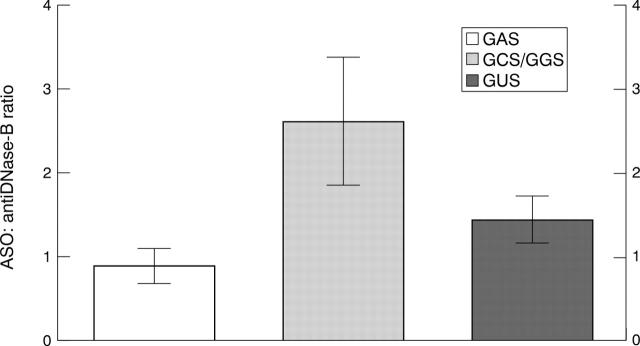

Figure 3 .

ASO: antiDNase B ratio in the GAS (n=6), NGAS (n=7), and GUS induced (n=28) PSRA patients. Data are means (SEM).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Arnold M. H., Tyndall A. Poststreptococcal reactive arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989 Aug;48(8):686–688. doi: 10.1136/ard.48.8.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEERMAN H. Erythema nodosum; a survey of some recent literature. Am J Med Sci. 1952 Apr;223(4):433–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnert A. L., Terry E. E., Persellin R. H. Acute rheumatic fever in adults. JAMA. 1975 Jun 2;232(9):925–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Dov I., Berry E. Acute rheumatic fever in adults over the age of 45 years: an analysis of 23 patients together with a review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1980 Nov;10(2):100–110. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(80)90003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisno A. L. Group A streptococcal infections and acute rheumatic fever. N Engl J Med. 1991 Sep 12;325(11):783–793. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199109123251106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deighton C. Beta haemolytic streptococci and reactive arthritis in adults. Ann Rheum Dis. 1993 Jun;52(6):475–482. doi: 10.1136/ard.52.6.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FEINSTEIN A. R., SPAGNUOLO M. The clinical patterns of acute rheumatic fever: a reapraisal. Medicine (Baltimore) 1962 Dec;41:279–305. doi: 10.1097/00005792-196212000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuer J., Spiera H. Acute rheumatic fever in adults: a resurgence in the Hasidic Jewish community. J Rheumatol. 1997 Feb;24(2):337–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaunt P. N., Seal D. V. Group G streptococcal infection of joints and joint prostheses. J Infect. 1986 Sep;13(2):115–123. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(86)92785-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homer C., Shulman S. T. Clinical aspects of acute rheumatic fever. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1991 Apr;29:2–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen T. L., Janssen M., de Jong A. J. Reactive arthritis associated with group C and group G beta-hemolytic streptococci. J Rheumatol. 1998 Jun;25(6):1126–1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen T. L., Janssen M., van Riel P. L. Grand rounds in rheumatology: acute rheumatic fever or post-streptococcal reactive arthritis: a clinical problem revisited. Br J Rheumatol. 1998 Mar;37(3):335–340. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch D. N., Holland C. D. Reactive arthritis, beta-haemolytic Streptococcus and Staphylococcus aureus. Br J Rheumatol. 1996 Sep;35(9):912–912. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.9.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NYDICK I., TANG J., STOLLERMAN G. H., WROBLEWSKI F., LADUE J. S. The influence of rheumatic fever on serum concentrations of the enzyme, glutamic oxalacetic transaminase. Circulation. 1955 Nov;12(5):795–806. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.12.5.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevoo M. L., van Riel P. L., van 't Hof M. A., van Rijswijk M. H., van Leeuwen M. A., Kuper H. H., van de Putte L. B. Validity and reliability of joint indices. A longitudinal study in patients with recent onset rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1993 Jul;32(7):589–594. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/32.7.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson S. J., Beeching N. J. Reactive arthritis complicating group G streptococcal septicaemia. J Infect. 1990 Mar;20(2):155–158. doi: 10.1016/0163-4453(90)93470-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos K. The diagnostic value of symptoms and signs in acute tonsillitis in children over the age of 10 and in adults. Scand J Infect Dis. 1985;17(3):259–267. doi: 10.3109/inf.1985.17.issue-3.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young L., Deighton C. M., Chuck A. J., Galloway A. Reactive arthritis and group G streptococcal pharyngitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992 Nov;51(11):1268–1268. doi: 10.1136/ard.51.11.1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]