Abstract

OBJECTIVES—To compare objectively the shape of the intercondylar notch in human osteoarthritic and non-osteoarthritic femora. METHODS—A sample of 96 human femora from a large skeletal population were selected for study. These femora included subjects with evidence of late stage osteoarthritis (that is, with eburnation present) and subjects with no such evidence. The distal end of the femur, viewed axially, was recorded with a video camera, and digitised computer images were produced. The outline of the intercondylar notch was extracted and represented mathematically as two functions. A functional principal components analysis was used to identify important modes of shape variation. These variations in shape were compared between eburnated and non-eburnated femora. RESULTS—A statistically significant difference in the shape of the intercondylar notch was found between the two groups. The difference related mostly to the shape of the edge of the medial condyle: in the non-osteoarthritic group this tended to exhibit a concavity; in the osteoarthritic group it tended to be straight. CONCLUSIONS—This observed difference may be a predisposing factor to the development of osteoarthritis. The morphology of the intercondylar notch is related to the functioning of and possible damage to the cruciate ligaments, and damage to the cruciate ligaments is a known risk factor for osteoarthritis. Alternatively, this difference may be due to bony remodelling secondary to the onset of osteoarthritis, perhaps in response to altered biomechanics.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (144.9 KB).

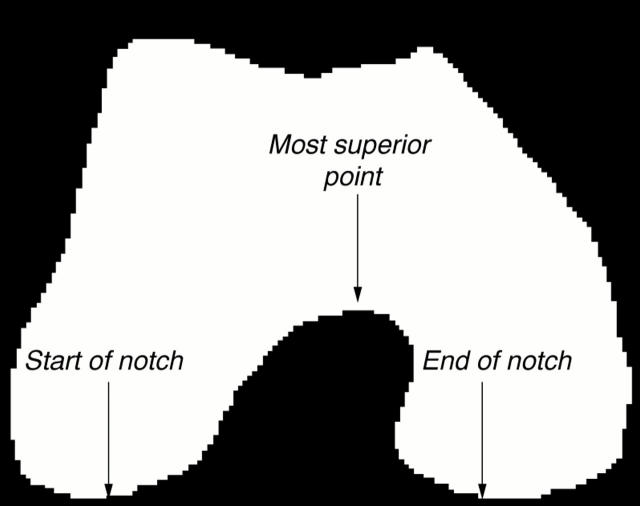

Figure 1 .

Example of digitised image.

Figure 2 .

Outline of the intercondylar notch.

Figure 3 .

Mean intercondylar notch shape.

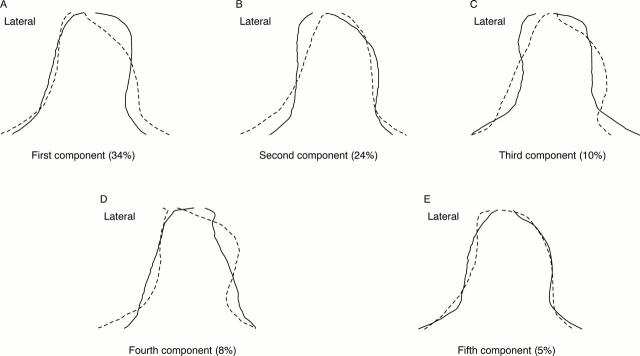

Figure 4 .

Illustration of first five principal components (with percentage of total variation). Solid line = mean + 2SDs of the principal component; dashed line = mean − 2SDs of the principal component.

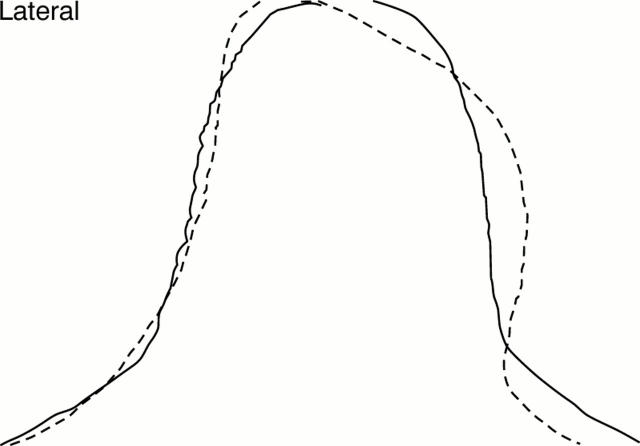

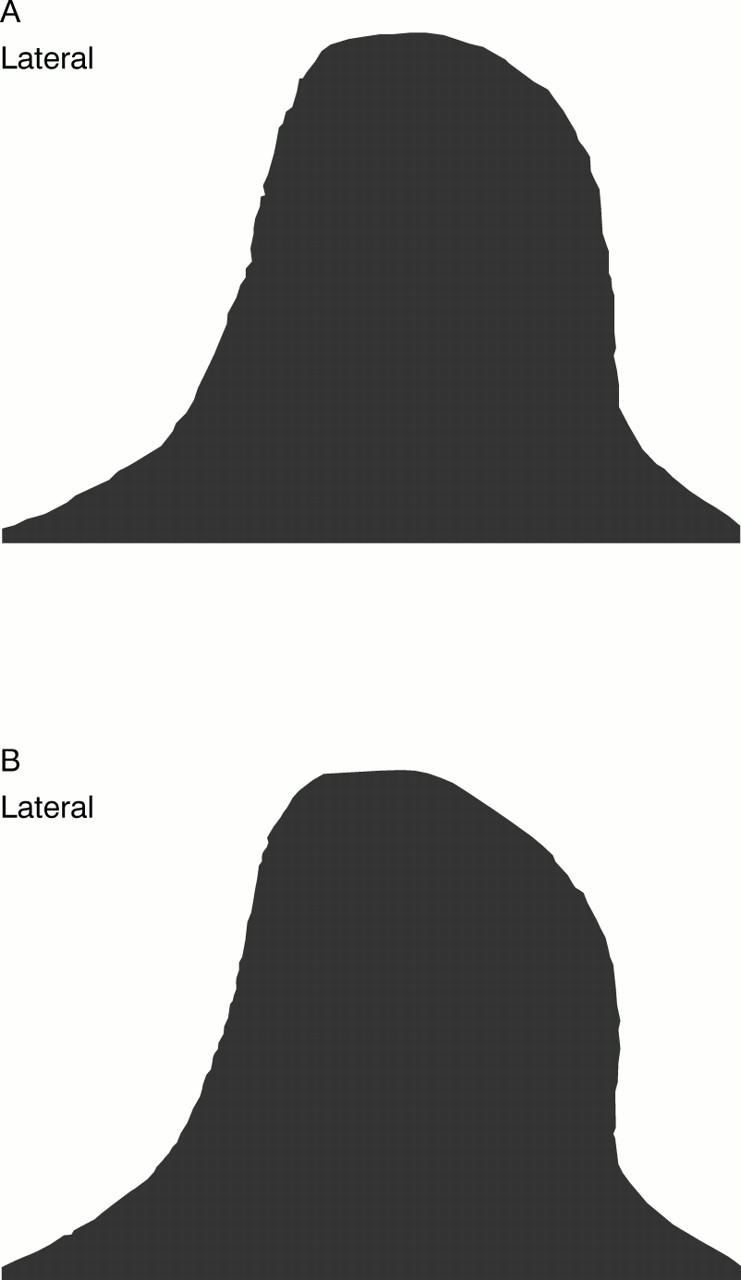

Figure 5 .

(A) Eburnated and (B) non-eburnated mean intercondylar notch shapes.

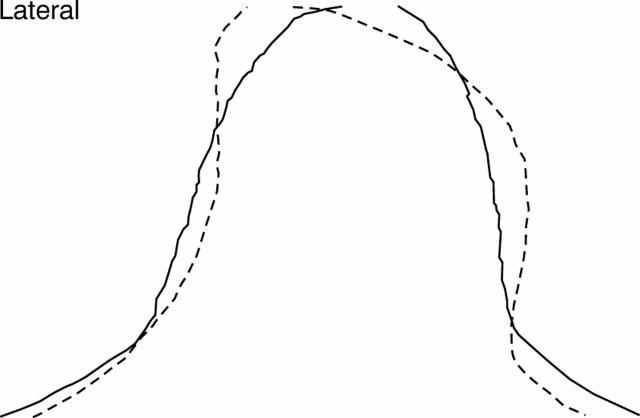

Figure 6 .

Illustration of discriminant function between eburnated and non-eburnated femora. Solid line = mean + 2SDs; dashed line = mean − 2SDs.

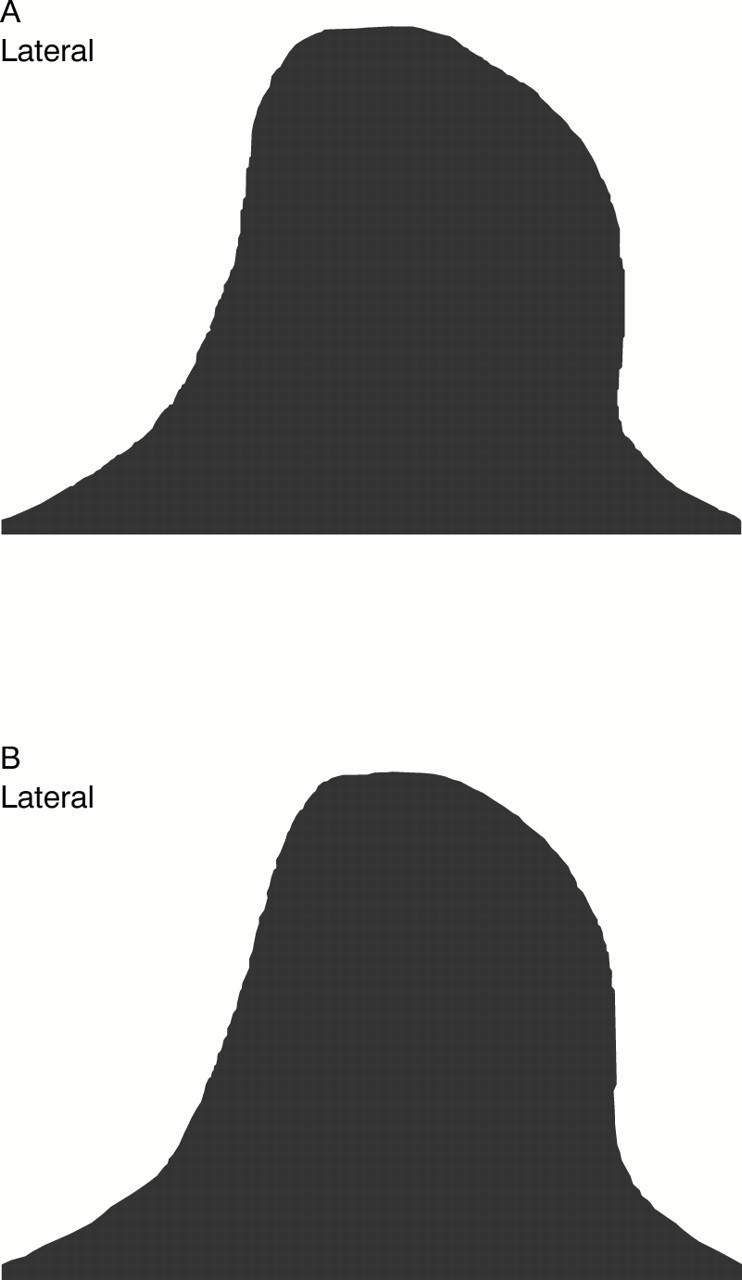

Figure 7 .

(A) Male and (B) female mean intercondylar notch shapes.

Figure 8 .

Illustration of discriminant function between men and women. Solid line = mean + 2SDs; dashed line = mean − 2SDs .

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson A. F., Lipscomb A. B., Liudahl K. J., Addlestone R. B. Analysis of the intercondylar notch by computed tomography. Am J Sports Med. 1987 Nov-Dec;15(6):547–552. doi: 10.1177/036354658701500605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt K. D., Braunstein E. M., Visco D. M., O'Connor B., Heck D., Albrecht M. Anterior (cranial) cruciate ligament transection in the dog: a bona fide model of osteoarthritis, not merely of cartilage injury and repair. J Rheumatol. 1991 Mar;18(3):436–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieppe P. Osteoarthritis: are we asking the wrong questions? Br J Rheumatol. 1984 Aug;23(3):161–163. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/23.3.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felson D. T., Zhang Y., Hannan M. T., Naimark A., Weissman B., Aliabadi P., Levy D. Risk factors for incident radiographic knee osteoarthritis in the elderly: the Framingham Study. Arthritis Rheum. 1997 Apr;40(4):728–733. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good L., Odensten M., Gillquist J. Intercondylar notch measurements with special reference to anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991 Feb;(263):185–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen K. Osteoarthrosis following insufficiency of the cruciate ligaments in man. A clinical study. Acta Orthop Scand. 1977;48(5):520–526. doi: 10.3109/17453677708989742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurmain R. D., Kilgore L. Skeletal evidence of osteoarthritis: a palaeopathological perspective. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995 Jun;54(6):443–450. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.6.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannus P., Järvinen M. Posttraumatic anterior cruciate ligament insufficiency as a cause of osteoarthritis in a knee joint. Clin Rheumatol. 1989 Jun;8(2):251–260. doi: 10.1007/BF02030082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaPrade R. F., Burnett Q. M., 2nd Femoral intercondylar notch stenosis and correlation to anterior cruciate ligament injuries. A prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 1994 Mar-Apr;22(2):198–203. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pond M. J., Nuki G. Experimentally-induced osteoarthritis in the dog. Ann Rheum Dis. 1973 Jul;32(4):387–388. doi: 10.1136/ard.32.4.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelbourne K. D., Davis T. J., Klootwyk T. E. The relationship between intercondylar notch width of the femur and the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament tears. A prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 1998 May-Jun;26(3):402–408. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260031001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepstone L., Rogers J., Kirwan J., Silverman B. The shape of the distal femur: a palaeopathological comparison of eburnated and non-eburnated femora. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999 Feb;58(2):72–78. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.2.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souryal T. O., Freeman T. R. Intercondylar notch size and anterior cruciate ligament injuries in athletes. A prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 1993 Jul-Aug;21(4):535–539. doi: 10.1177/036354659302100410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector T. D., Hart D. J., Doyle D. V. Incidence and progression of osteoarthritis in women with unilateral knee disease in the general population: the effect of obesity. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994 Sep;53(9):565–568. doi: 10.1136/ard.53.9.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitz C. C., Lind B. K., Sacks B. M. Symmetry of the femoral notch width index. Am J Sports Med. 1997 Sep-Oct;25(5):687–690. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada M., Tatsuo H., Baba H., Asamoto K., Nojyo Y. Femoral intercondylar notch measurements in osteoarthritic knees. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999 Jun;38(6):554–558. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.6.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Saase J. L., van Romunde L. K., Cats A., Vandenbroucke J. P., Valkenburg H. A. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis: Zoetermeer survey. Comparison of radiological osteoarthritis in a Dutch population with that in 10 other populations. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989 Apr;48(4):271–280. doi: 10.1136/ard.48.4.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]