Abstract

OBJECTIVE—Molecular biology techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and ligase chain reaction (LCR) are routinely used in research for detection of C trachomatis DNA in synovial samples, and these methods are now in use in some clinical laboratories. This study aimed at determining the method best suited to molecular diagnosis of C trachomatis by examining four standard DNA preparation methods using chlamydia spiked synovial tissue and chlamydia infected monocytes. METHODS—Synovial tissue from a chlamydia negative patient with rheumatoid arthritis was spiked with defined numbers of C trachomatis elementary bodies (EB). Purified human peripheral monocytes from normal donors were infected with the organism at a multiplicity of infection 1:1 in vitro and harvested after four days. DNA was prepared from all samples by four methods: (1) QIAmp tissue kit; (2) homogenisation in 65°C phenol; (3) incubation at 97°C; (4) proteinase K digestion at 97°C. DNA from methods 1 and 2 was subjected to PCR using two different primer sets, each targeting the C trachomatis omp1 gene. LCR was done on DNA prepared by each method. RESULTS—In synovial tissue samples spiked with EB, and in monocytes persistently infected with the organism, preparation of template using the QIAmp tissue kit (method 1) and the hot phenol extraction technique (method 2) allowed sensitive detection of C trachomatis DNA. These methods also produced template from both sample types for LCR. DNA prepared by heat denaturation (method 3) allowed only low sensitivity chlamydia detection in LCR and did not work at all for PCR. Proteinase K digestion plus heat denaturation (method 4) gave template that did not allow amplification in either PCR or LCR assays. CONCLUSIONS—The sensitivity of detection for C trachomatis DNA in synovial tissue by PCR and LCR depends strongly on the method used for preparation of the amplification template. LCR targeting the multicopy chlamydial plasmid and two nested PCR assay systems targeting the single copy omp1 gene showed roughly equivalent sensitivity. Importantly, template preparation method and the specific PCR primer system used for screening must be optimised in relation to one another for highest sensitivity.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (149.7 KB).

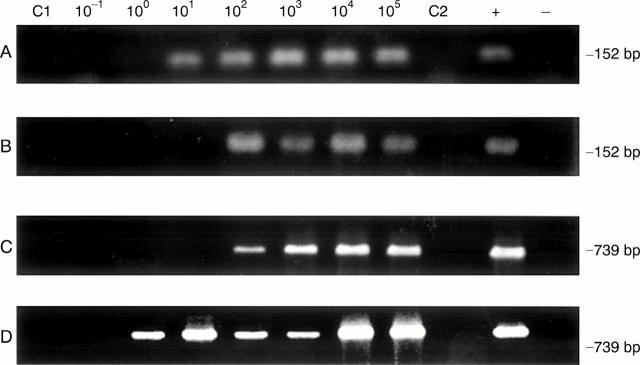

Figure 1 .

Representative polymerase chain reaction sensitivities in detection of C trachomatis in synovial tissue samples spiked with elementary bodies (EB) using template DNA prepared by the QIAmp tissue kit (method 1) and homogenisation in hot phenol (method 2), with set 1 and set 2 primers. (A) DNA preparation method 1 with primer set 1; (B) DNA preparation method 2 with primer set 1; (C) DNA preparation method 1 with primer set 2; (D) DNA preparation method 2 with primer set 2. Assays were performed as given in "Methods"; amplification product size in base pairs (bp) is given at the right. In each panel lanes C1 and C2 used template DNA from synovial tissue of the patient with rheumatoid arthritis without added EB, and primer sets 1 and 2, respectively. The positive (+) control and negative (−) control lanes contained pure EB DNA and water only, respectively, as amplification template.

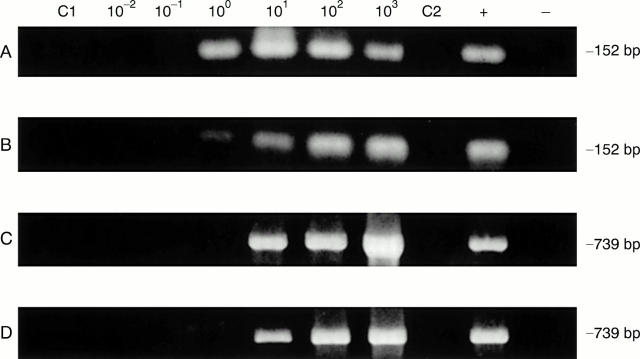

Figure 2 .

Representative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) sensitivities in detection of C trachomatis using chlamydia infected monocytes in synovial tissue samples and template DNA prepared by the QIAmp tissue kit (method 1) as well as homogenisation in hot phenol (method 2), with set 1 and set 2 primers. (A) DNA preparation method 1 with primer set 1; (B) DNA preparation method 2 with primer set 1; (C) DNA preparation method 1 with primer set 2; (D) DNA preparation method 2 with primer set 2. Assays were performed as given in "Methods"; amplification product size in base pairs (bp) is given at right. In each panel lanes C1 and C2 PCR was done using the set 1 and set 2 primers, respectively, and template DNA from synovial tissue of the patient with rheumatoid arthritis without added EB. The positive (+) control and negative (−) control lanes contained pure EB DNA and water only, respectively, as amplification template.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bas S., Griffais R., Kvien T. K., Glennås A., Melby K., Vischer T. L. Amplification of plasmid and chromosome Chlamydia DNA in synovial fluid of patients with reactive arthritis and undifferentiated seronegative oligoarthropathies. Arthritis Rheum. 1995 Jul;38(7):1005–1013. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bas S., Ninet B., Delaspre O., Vischer T. L. Evaluation of commercially available tests for Chlamydia nucleic acid detection in synovial fluid of patients. Br J Rheumatol. 1997 Feb;36(2):198–202. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/36.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler A. M., Schumacher H. R., Jr, Whittum-Hudson J. A., Salameh W. A., Hudson A. P. Case report: in situ hybridization for detection of inapparent infection with Chlamydia trachomatis in synovial tissue of a patient with Reiter's syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 1995 Nov;310(5):206–213. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199511000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler A. M., Whittum-Hudson J. A., Nanagara R., Schumacher H. R., Hudson A. P. Intracellular location of inapparently infecting Chlamydia in synovial tissue from patients with Reiter's syndrome. Immunol Res. 1994;13(2-3):163–171. doi: 10.1007/BF02918277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo L., Coutlee F., Yolken R. H., Quinn T., Viscidi R. P. Diagnosis of Chlamydia trachomatis cervical infection by detection of amplified DNA with an enzyme immunoassay. J Clin Microbiol. 1990 Sep;28(9):1968–1973. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.1968-1973.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branigan P. J., Gérard H. C., Hudson A. P., Schumacher H. R., Jr, Pando J. Comparison of synovial tissue and synovial fluid as the source of nucleic acids for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis by polymerase chain reaction. Arthritis Rheum. 1996 Oct;39(10):1740–1746. doi: 10.1002/art.1780391018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon F. B., Quan A. L., Steinman T. I., Philip R. N. Chlamydial isolates from Reiter's syndrome. Br J Vener Dis. 1973 Aug;49(4):376–380. doi: 10.1136/sti.49.4.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gérard H. C., Branigan P. J., Schumacher H. R., Jr, Hudson A. P. Synovial Chlamydia trachomatis in patients with reactive arthritis/Reiter's syndrome are viable but show aberrant gene expression. J Rheumatol. 1998 Apr;25(4):734–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gérard H. C., Köhler L., Branigan P. J., Zeidler H., Schumacher H. R., Hudson A. P. Viability and gene expression in Chlamydia trachomatis during persistent infection of cultured human monocytes. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1998 Oct;187(2):115–120. doi: 10.1007/s004300050082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gérard H. C., Whittum-Hudson J. A., Hudson A. P. Genes required for assembly and function of the protein synthetic system in Chlamydia trachomatis are expressed early in elementary to reticulate body transformation. Mol Gen Genet. 1997 Aug;255(6):637–642. doi: 10.1007/s004380050538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler L., Nettelnbreker E., Hudson A. P., Ott N., Gérard H. C., Branigan P. J., Schumacher H. R., Drommer W., Zeidler H. Ultrastructural and molecular analyses of the persistence of Chlamydia trachomatis (serovar K) in human monocytes. Microb Pathog. 1997 Mar;22(3):133–142. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler L., Zeidler H., Hudson A. P. Aetiological agents: their molecular biology and phagocyte-host interaction. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1998 Nov;12(4):589–609. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3579(98)80039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers J. G., Nietfeld L., Dreses-Werringloer U., Koehler L., Wollenhaupt J., Zeidler H., Hammer M. Optimised sample preparation of synovial fluid for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis DNA by polymerase chain reaction. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999 Feb;58(2):103–108. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.2.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers J. G., Scharmann K., Wollenhaupt J., Nettelnbreker E., Hopf S., Zeidler H. Sensitivities of PCR, MicroTrak, ChlamydiaEIA, IDEIA, and PACE 2 for purified Chlamydia trachomatis elementary bodies in urine, peripheral blood, peripheral blood leukocytes, and synovial fluid. J Clin Microbiol. 1995 Dec;33(12):3186–3190. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3186-3190.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole E. S., Highton J., Wilkins R. J., Lamont I. L. A search for Chlamydia trachomatis in synovial fluids from patients with reactive arthritis using the polymerase chain reaction and antigen detection methods. Br J Rheumatol. 1992 Jan;31(1):31–34. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/31.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz E., Nettelnbreker E., Zeidler H., Hammer M., Manor E., Wollenhaupt J. Intracellular persistence of chlamydial major outer-membrane protein, lipopolysaccharide and ribosomal RNA after non-productive infection of human monocytes with Chlamydia trachomatis serovar K. J Med Microbiol. 1993 Apr;38(4):278–285. doi: 10.1099/00222615-38-4-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher H. R., Jr, Kulka J. P. Needle biopsy of the synovial membrane--experience with the Parker-Pearson technic. N Engl J Med. 1972 Feb 24;286(8):416–419. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197202242860807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson N. Z., Kingsley G. H., Jones H. W., Sieper J., Braun J., Ward M. E. The detection of DNA from a range of bacterial species in the joints of patients with a variety of arthritides using a nested, broad-range polymerase chain reaction. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999 Mar;38(3):260–266. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson N. Z., Kingsley G. H., Sieper J., Braun J., Ward M. E. Lack of correlation between the detection of Chlamydia trachomatis DNA in synovial fluid from patients with a range of rheumatic diseases and the presence of an antichlamydial immune response. Arthritis Rheum. 1998 May;41(5):845–854. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<845::AID-ART11>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]