Abstract

Background: Rheumatoid synovial fluid contains both soluble and insoluble immune complexes that can activate infiltrating immune cells such as neutrophils.

Objectives: To determine if these different complexes activate neutrophils through similar or different receptor signalling pathways. In particular, to determine the circumstances which result in the secretion of tissue damaging reactive oxygen metabolites and granule enzymes.

Methods: Blood neutrophils were incubated with synthetic soluble and insoluble immune complexes and the ability to generate reactive oxidants tested by luminescence or spectrophotometric assays that distinguished between intracellular and extracellular production. Degranulation of myeloperoxidase and lactoferrin was determined by western blotting. The roles of FcγRII (CD32) and FcγRIIIb (CD16) were determined by incubation with Fab/F(ab`)2 fragments before activation. The effect of cytokine priming was determined by incubation with GM-CSF.

Results: Insoluble immune complexes activated unprimed neutrophils, but most of the oxidants produced were intracellular. This activation required FcγRIIIb, but not FcγRII function. Soluble complexes failed to activate unprimed neutrophils but generated a rapid and extensive secretion of reactive oxygen metabolites when the cells were primed with granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF). This activity required both FcγRII and FcγRIIIb function. Insoluble immune complexes activated the release of granule enzymes from primed or unprimed neutrophils, but the kinetics of release did not parallel those of secretion of reactive oxygen metabolites. Only primed neutrophils released enzymes in response to soluble complexes.

Conclusions: Soluble and insoluble immune complexes activate neutrophils by separate receptor signalling pathways. Profound changes in neutrophil responsiveness to these complexes occur after cytokine priming.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (207.6 KB).

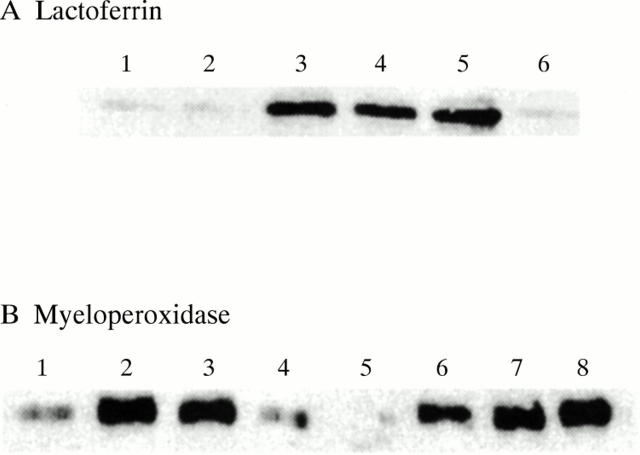

Figure 1 .

Activation of the neutrophil respiratory burst by immune complexes. (A and B) Neutrophils were incubated in HBSS at 5x105 cells/ml in medium that was supplemented with either 10 µM luminol or 10 µM isoluminol. (C) Cells were incubated at 106 cells/ml in HBSS supplemented with 75 µM cytochrome c. Neutrophils were incubated for 45 minutes in the absence (unprimed) or presence (primed) of GM-CSF (50 U/ml). They were then stimulated with either soluble or insoluble immune complexes, as described in "Materials and methods". Typical result of at least six separate experiments are shown.

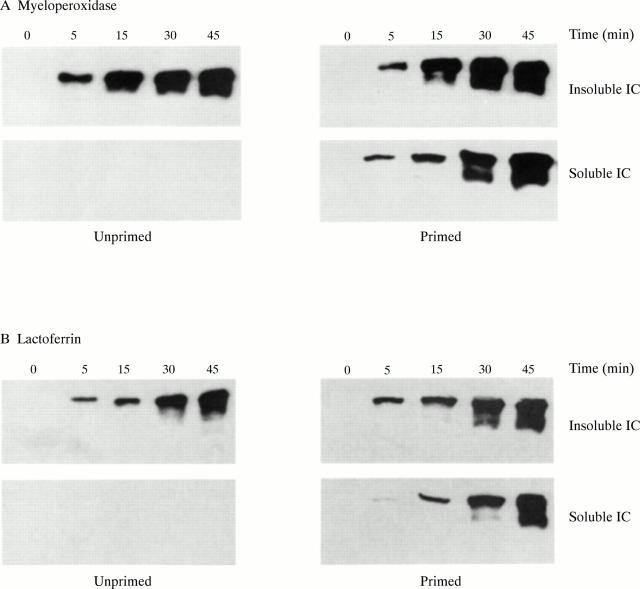

Figure 2 .

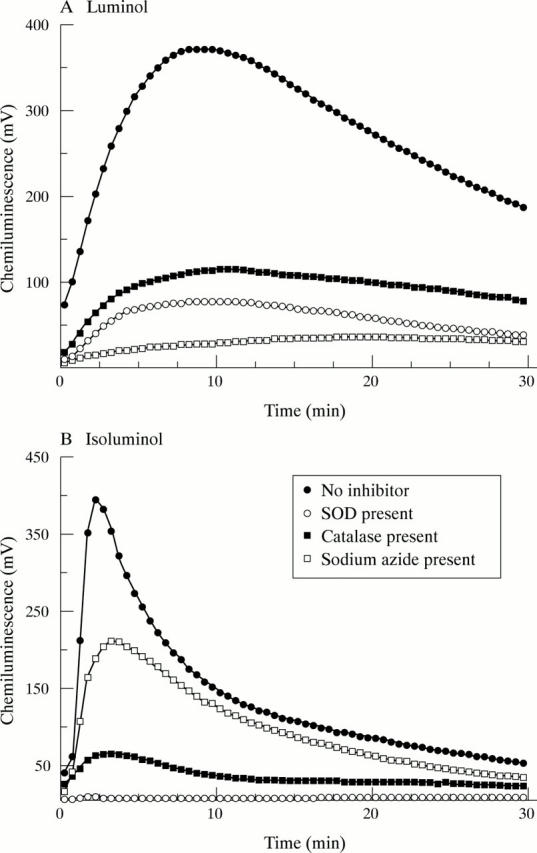

Effect of oxidant scavengers on chemiluminescence: activation by soluble immune complexes. GM-CSF primed neutrophils were incubated at 5x105 cells/ml in HBSS supplemented with either 10 µM luminol (A) or 10 µM isoluminol (B), in the absence or presence of SOD, catalase, or sodium azide, as described in "Materials and methods". At time zero, cells were stimulated by the addition of soluble immune complexes. Typical results of at least six separate experiments are shown.

Figure 3 .

Effect of oxidant scavengers on chemiluminescence: activation by insoluble immune complexes. GM-CSF primed neutrophils were incubated at 5x105 cells/ml in HBSS supplemented with either 10 µM luminol (A) or 10 µM isoluminol (B), in the absence or presence of SOD, catalase, or sodium azide, as described in "Materials and methods". At time zero, cells were stimulated by the addition of insoluble immune complexes. Typical results of at least six separate experiments are shown.

Figure 4 .

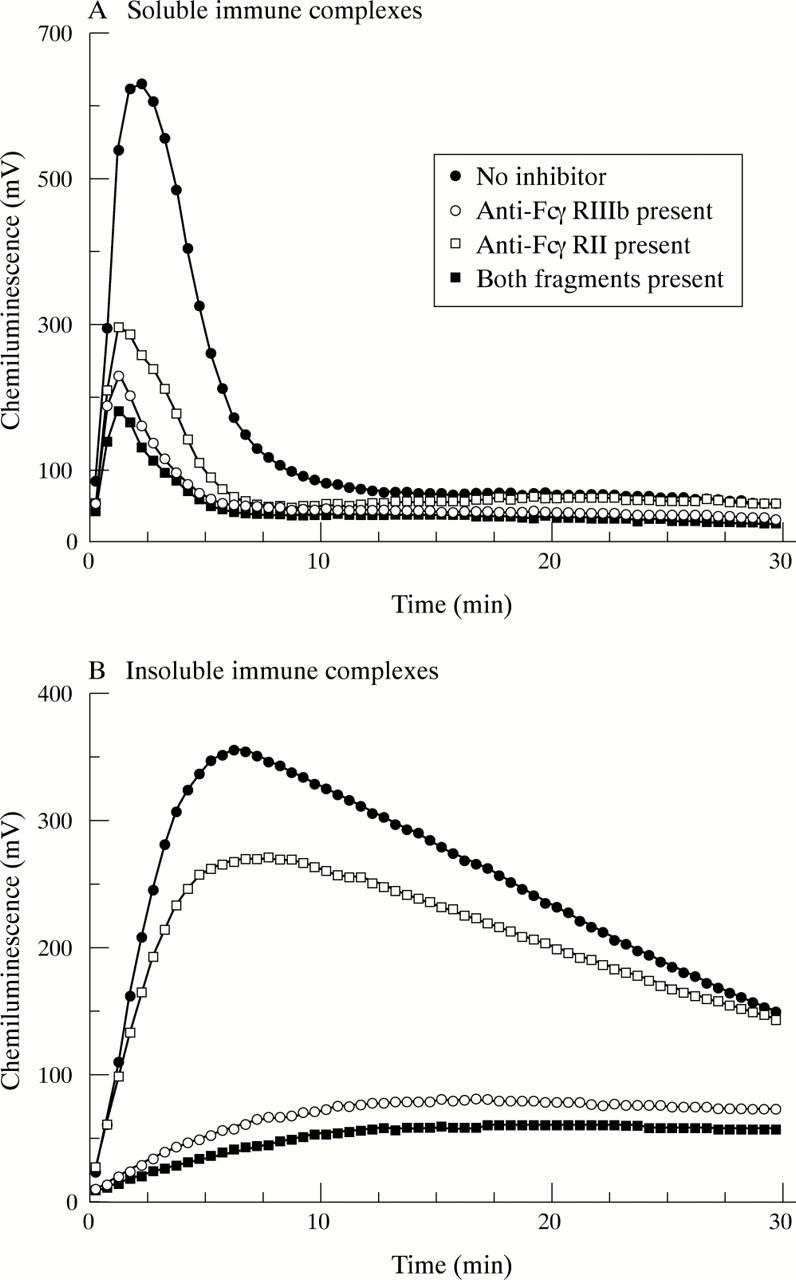

Effect of FcγR blocking on neutrophil activation by immune complexes. GM-CSF primed neutrophils were incubated in the absence or presence of either an F(ab`)2 fragment of 3G8 (anti-FcγRIIIb) or an Fab fragment of IV.3 (anti-FcγRII) or with both fragments, as described in "Materials and methods". Luminol chemiluminescence was then measured after the addition of either soluble (A) or insoluble (B) immune complexes. Typical results of at least six separate experiments are shown.

Figure 5 .

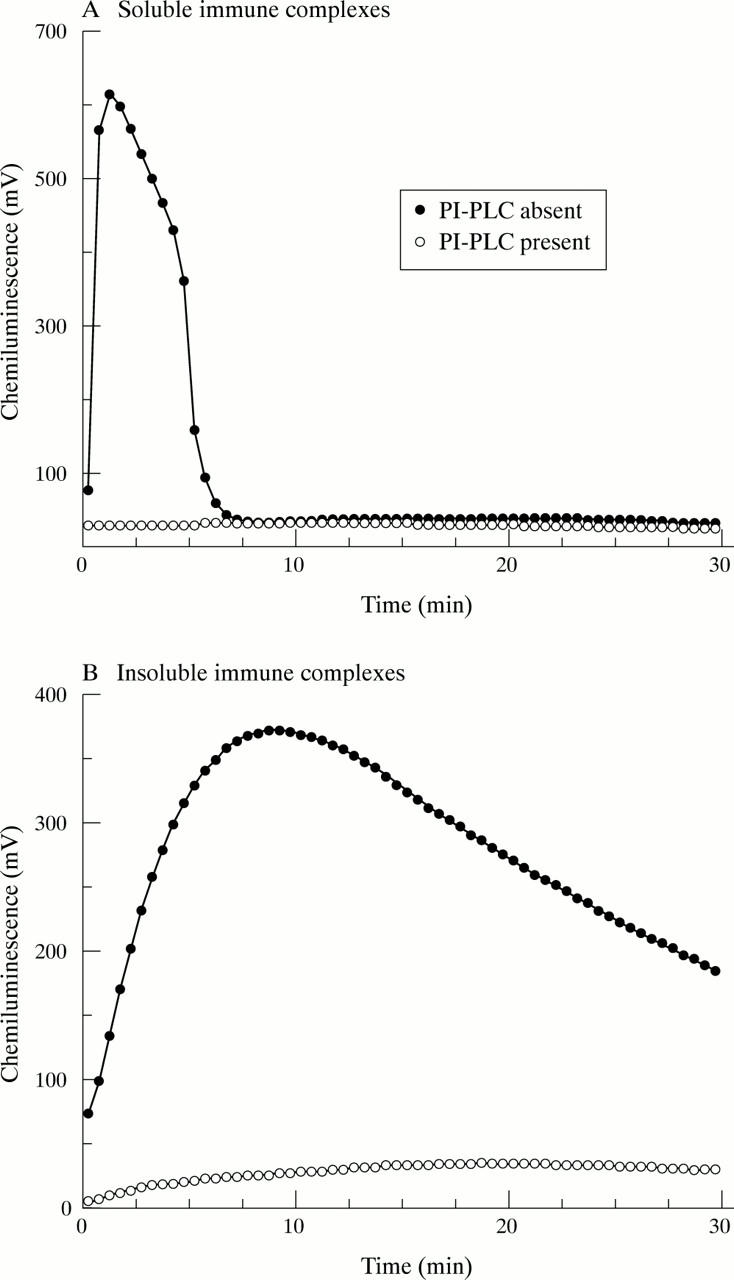

Effect of FcγRIIIb depletion on neutrophil activation by immune complexes. GM-CSF primed neutrophils were incubated in the absence or presence of PI-PLC as described in "Materials and methods". They were then stimulated by the addition of either soluble (A) or insoluble (B) immune complexes and luminol chemiluminescence measured. Typical results of at least six separate experiments are shown.

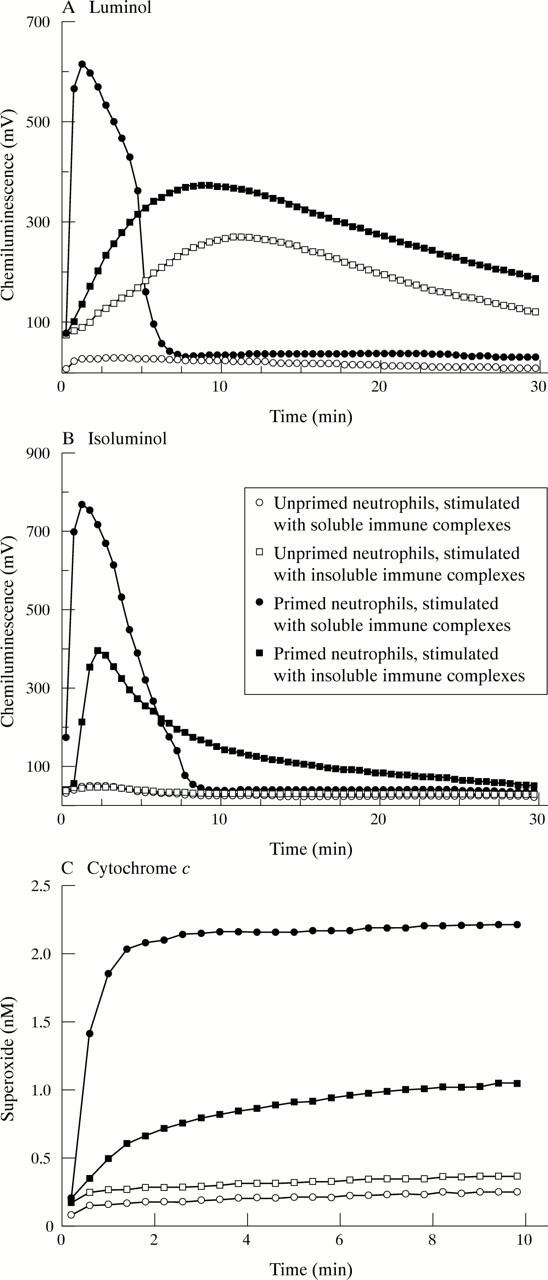

Figure 6 .

Activation of degranulation by immune complexes. Neutrophils were incubated in the presence and absence of GM-CSF and then stimulated for 45 minutes by the addition of either soluble or insoluble immune complexes. Cell-free supernatants were then analysed for the presence of either lactoferrin (A) or myeloperoxidase (B) by immunoblotting. In (A) samples were loaded as follows: 1, unprimed neutrophils, no additions; 2, unprimed neutrophils, soluble immune complexes; 3, unprimed neutrophils, insoluble immune complexes; 4, primed neutrophils, soluble immune complexes; 5, primed neutrophils insoluble immune complexes; 6, primed neutrophils no additions. In (B) samples were loaded as follows: 1–4, unprimed neutrophils; 5–8, primed neutrophils; 1, 5, control, no additions; 2, 6, phorbol myristate acetate (0.1 µg/ml); 3, 7, insoluble immune complexes; 4, 8, soluble immune complexes. Typical results of at least six separate experiments are shown.

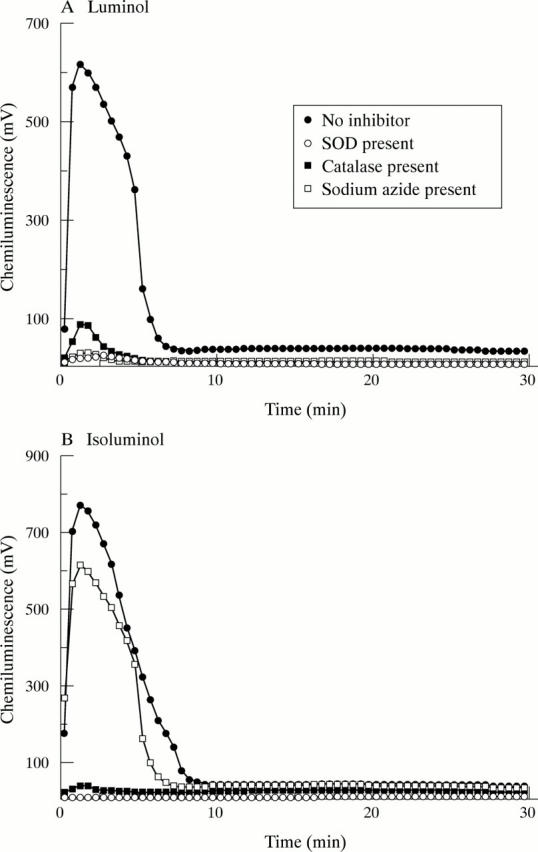

Figure 7 .

Time course of degranulation in response to immune complexes. Neutrophils were primed by incubation in the presence and absence of GM-CSF and then incubated in the absence (control, not shown) or presence of either insoluble or soluble immune complexes. At time intervals of up to 45 minutes, cell-free supernatants were tested for the presence of either myeloperoxidase (A) or lactoferrin (B) by western blotting. Typical results of at least three separate experiments are shown.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Albrecht D., Jungi T. W. Luminol-enhanced chemiluminescence induced in peripheral blood-derived human phagocytes: obligatory requirement of myeloperoxidase exocytosis by monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 1993 Oct;54(4):300–306. doi: 10.1002/jlb.54.4.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babior B. M., Kipnes R. S., Curnutte J. T. Biological defense mechanisms. The production by leukocytes of superoxide, a potential bactericidal agent. J Clin Invest. 1973 Mar;52(3):741–744. doi: 10.1172/JCI107236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babior B. M. Phagocytes and oxidative stress. Am J Med. 2000 Jul;109(1):33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00481-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauerová K., Bezek A. Role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in etiopathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Gen Physiol Biophys. 1999 Oct;18(Spec No):15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu A. D., McColl S. R. Differential expression of two major cytokines produced by neutrophils, interleukin-8 and the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, in neutrophils isolated from the synovial fluid and peripheral blood of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1994 Jun;37(6):855–859. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. A. Activation of the neutrophil respiratory burst oxidase. J Infect Dis. 1999 Mar;179 (Suppl 2):S309–S317. doi: 10.1086/513849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett-Torabi E., Fantone J. C. Soluble and insoluble immune complexes activate human neutrophil NADPH oxidase by distinct Fc gamma receptor-specific mechanisms. J Immunol. 1990 Nov 1;145(9):3026–3032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren C., Karlsson A. Respiratory burst in human neutrophils. J Immunol Methods. 1999 Dec 17;232(1-2):3–14. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(99)00146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dularay B., Elson C. J., Dieppe P. A. Enhanced oxidative response of polymorphonuclear leukocytes from synovial fluids of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmunity. 1988;1(3):159–169. doi: 10.3109/08916938808997161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S. W. Cell signalling by integrins and immunoglobulin receptors in primed neutrophils. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995 Sep;20(9):362–367. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S. W., Hallett M. B. Seeing the wood for the trees: the forgotten role of neutrophils in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Today. 1997 Jul;18(7):320–324. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S. W. Luminol- and lucigenin-dependent chemiluminescence of neutrophils: role of degranulation. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1987 Jan;22(1):35–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S. W., Nurcombe H. L., Hart C. A. Oxidative inactivation of myeloperoxidase released from human neutrophils. Biochem J. 1987 Aug 1;245(3):925–928. doi: 10.1042/bj2450925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S. W., Watson F., Gasmi L., Moulding D. A., Quayle J. A. Activation of human neutrophils by soluble immune complexes: role of Fc gamma RII and Fc gamma RIIIb in stimulation of the respiratory burst and elevation of intracellular Ca2+. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997 Dec 15;832:341–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb46262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards SW. The O-2 Generating NADPH Oxidase of Phagocytes: Structure and Methods of Detection. Methods. 1996 Jun;9(3):563–577. doi: 10.1006/meth.1996.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follin P., Briheim G., Sandstedt S., Dahlgren C. Human neutrophil chemiluminescence and f-Meth-Leu-Phe receptor exposure in bacterial infections. APMIS. 1989 Jul;97(7):585–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1989.tb00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follin P., Dahlgren C. Altered O2-/H2O2 production ratio by in vitro and in vivo primed human neutrophils. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990 Mar 30;167(3):970–976. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90618-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg I., Misgav R., Gibbs D. F., Varani J., Kohen R. Chemiluminescence in activated human neutrophils: role of buffers and scavengers. Inflammation. 1993 Jun;17(3):227–243. doi: 10.1007/BF00918987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallett M. B., Lloyds D. Neutrophil priming: the cellular signals that say 'amber' but not 'green'. Immunol Today. 1995 Jun;16(6):264–268. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettle A. J., Winterbourn C. C. Superoxide-dependent hydroxylation by myeloperoxidase. J Biol Chem. 1994 Jun 24;269(25):17146–17151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowanko I. C., Ferrante A., Clemente G., Youssef P. P., Smith M. Tumor necrosis factor priming of peripheral blood neutrophils from rheumatoid arthritis patients. J Clin Immunol. 1996 Jul;16(4):216–221. doi: 10.1007/BF01541227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyds D., Davies E. V., Williams B. D., Hallett M. B. Tyrosine phosphorylation in neutrophils from synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1996 Sep;35(9):846–852. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.9.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist H., Dahlgren C. Isoluminol-enhanced chemiluminescence: a sensitive method to study the release of superoxide anion from human neutrophils. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;20(6):785–792. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)02189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist H., Follin P., Khalfan L., Dahlgren C. Phorbol myristate acetate-induced NADPH oxidase activity in human neutrophils: only half the story has been told. J Leukoc Biol. 1996 Feb;59(2):270–279. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsukawa A., Yoshimura T., Maeda T., Takahashi T., Ohkawara S., Yoshinaga M. Analysis of the cytokine network among tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-1beta, interleukin-8, and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in monosodium urate crystal-induced rabbit arthritis. Lab Invest. 1998 May;78(5):559–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally J. A., Bell A. L. Myeloperoxidase-based chemiluminescence of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and monocytes. J Biolumin Chemilumin. 1996 Mar-Apr;11(2):99–106. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1271(199603)11:2<99::AID-BIO404>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miesel R., Hartung R., Kroeger H. Priming of NADPH oxidase by tumor necrosis factor alpha in patients with inflammatory and autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Inflammation. 1996 Aug;20(4):427–438. doi: 10.1007/BF01486744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr W., Menninger H. Polymorphonuclear granulocytes at the pannus-cartilage junction in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1980 Dec;23(12):1413–1414. doi: 10.1002/art.1780231224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurcombe H. L., Bucknall R. C., Edwards S. W. Neutrophils isolated from the synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: priming and activation in vivo. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991 Mar;50(3):147–153. doi: 10.1136/ard.50.3.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurcombe H. L., Edwards S. W. Role of myeloperoxidase in intracellular and extracellular chemiluminescence of neutrophils. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989 Jan;48(1):56–62. doi: 10.1136/ard.48.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillinger M. H., Abramson S. B. The neutrophil in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1995 Aug;21(3):691–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pricop L., Redecha P., Teillaud J. L., Frey J., Fridman W. H., Sautès-Fridman C., Salmon J. E. Differential modulation of stimulatory and inhibitory Fc gamma receptors on human monocytes by Th1 and Th2 cytokines. J Immunol. 2001 Jan 1;166(1):531–537. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quayle J. A., Watson F., Bucknall R. C., Edwards S. W. Neutrophils from the synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis express the high affinity immunoglobulin G receptor, Fc gamma RI (CD64): role of immune complexes and cytokines in induction of receptor expression. Immunology. 1997 Jun;91(2):266–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J. J., Watson F., Bucknall R. C., Edwards S. W. Stimulation of neutrophils by insoluble immunoglobulin aggregates from synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Clin Invest. 1992 May;22(5):314–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1992.tb01468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J. J., Watson F., Bucknall R. C., Edwards S. W. Stimulation of reactive oxidant production in neutrophils by soluble and insoluble immune complexes occurs via different receptors/signal transduction systems. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1994 Mar;8(3):249–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1994.tb00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J. J., Watson F., Phelan M., Bucknall R. C., Edwards S. W. Activation of neutrophils by soluble and insoluble immunoglobulin aggregates from synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1993 May;52(5):347–353. doi: 10.1136/ard.52.5.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J., Watson F., Bucknall R. C., Edwards S. W. Activation of neutrophil reactive-oxidant production by synovial fluid from patients with inflammatory joint disease. Soluble and insoluble immunoglobulin aggregates activate different pathways in primed and unprimed cells. Biochem J. 1992 Sep 1;286(Pt 2):345–351. doi: 10.1042/bj2860345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tak P. P., Smeets T. J., Daha M. R., Kluin P. M., Meijers K. A., Brand R., Meinders A. E., Breedveld F. C. Analysis of the synovial cell infiltrate in early rheumatoid synovial tissue in relation to local disease activity. Arthritis Rheum. 1997 Feb;40(2):217–225. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y., Kasahara T., Sawai T., Rikimaru A., Mukaida N., Matsushima K., Sasaki T. The participation of IL-8 in the synovial lesions at an early stage of rheumatoid arthritis. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1999 May;188(1):75–87. doi: 10.1620/tjem.188.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson F., Edwards S. W. Stimulation of primed neutrophils by soluble immune complexes: priming leads to enhanced intracellular Ca2+ elevations, activation of phospholipase D, and activation of the NADPH oxidase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998 Jun 29;247(3):819–826. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson F., Gasmi L., Edwards S. W. Stimulation of intracellular Ca2+ levels in human neutrophils by soluble immune complexes. Functional activation of FcgammaRIIIb during priming. J Biol Chem. 1997 Jul 18;272(29):17944–17951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.17944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lent P. L., van Vuuren A. J., Blom A. B., Holthuysen A. E., van de Putte L. B., van de Winkel J. G., van den Berg W. B. Role of Fc receptor gamma chain in inflammation and cartilage damage during experimental antigen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000 Apr;43(4):740–752. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200004)43:4<740::AID-ANR4>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meurs J., van Lent P., Holthuysen A., Lambrou D., Bayne E., Singer I., van den Berg W. Active matrix metalloproteinases are present in cartilage during immune complex-mediated arthritis: a pivotal role for stromelysin-1 in cartilage destruction. J Immunol. 1999 Nov 15;163(10):5633–5639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]