Abstract

Background: It has previously been shown that many osteoclast precursors are included in the granulation tissue within the pseudocapsule obtained at revision arthroplasty from hips with osteolysis. In vitro culture of only cells isolated from the granulation tissue has been previously shown to generate many mature osteoclasts.

Objective: To investigate the presence or otherwise of supporting cells, similar to stromal cells, which differentiate osteoclasts within the granulation tissue.

Methods: Cells isolated from the granulation tissue were cultured alone, and after four weeks fibroblast-like cells (granulation fibroblasts) remained. Rat non-adherent bone marrow cells (NA-BMCs) were co-cultured with the granulation fibroblasts with or without 1α,25(OH)2D3 (10-8 M) or heat treated ROS 17/2.8 cell conditioned medium (ht ROSCM), or both. Multinucleated cells (MNCs), which formed, were assessed by biochemical and functional characterisation of osteoclasts. Receptor activator of NFκB ligand (RANKL) was investigated by immunohistochemistry.

Results: Co-culture of NA-BMCs and granulation fibroblasts caused the formation of tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) positive MNCs, which had the calcitonin receptor (CTR), the Kat-1 antigen, which is specific to the surface of rat osteoclasts, and the ability to form pits in the presence of both 1α,25(OH)2D3 and ht ROSCM or in the presence of just ht ROSCM. RANKL was detected in fibroblast-like cells in the granulation tissue.

Conclusion: These data suggest that granulation fibroblasts support osteoclast differentiation, as do osteoblasts/stromal cells, and may play a part in aseptic loosening.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (242.9 KB).

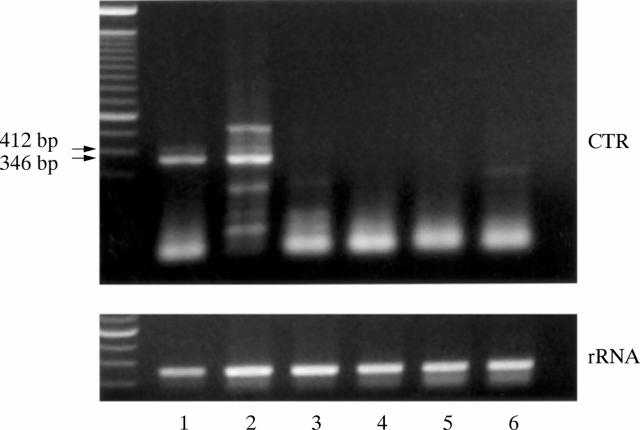

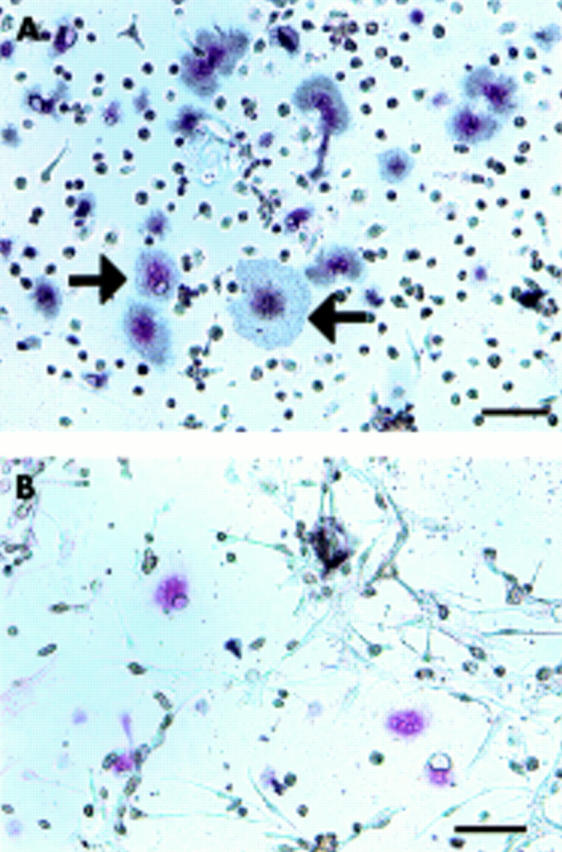

Figure 1 .

Preparation of granulation fibroblasts. Cells isolated from the granulation tissue staining for TRAP (A) after culture for one week and (B) after culture for four weeks. Bar = 10 µm. TRAP positive MNCs (arrow) appeared in the culture of the isolated cells from the granulation tissue after culture for one week (A). After culture for four weeks, neither TRAP positive mononuclear cells nor MNCs were seen, only the granulation fibroblasts remaining in the culture (B).

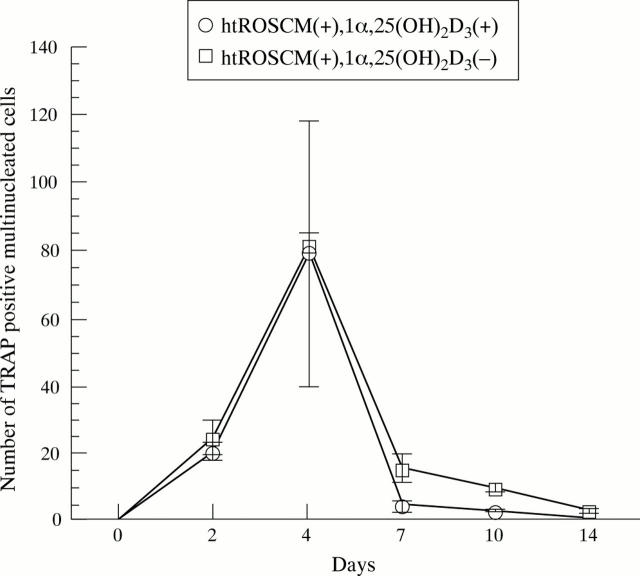

Figure 2 .

Expression of CTR mRNA in granulation fibroblasts. Expression of CTR mRNA by RT-PCR (50 cycle). Lane 1, giant cell tumour tissue (positive control); lane 2, granulation tissue; lane 3–6, granulation fibroblast culture (lane 3, with no supplementation; lane 4, with 1α,25 (OH)2D3; lane 5, with ht ROSCM; lane 6, with 1α,25 (OH)2D3 and ht ROSCM). Giant cell tumour tissue and granulation tissue showed two signals (346 bp and 412 bp) of CTR, but the culture of granulation fibroblasts alone did not show any signal under any of the conditions.

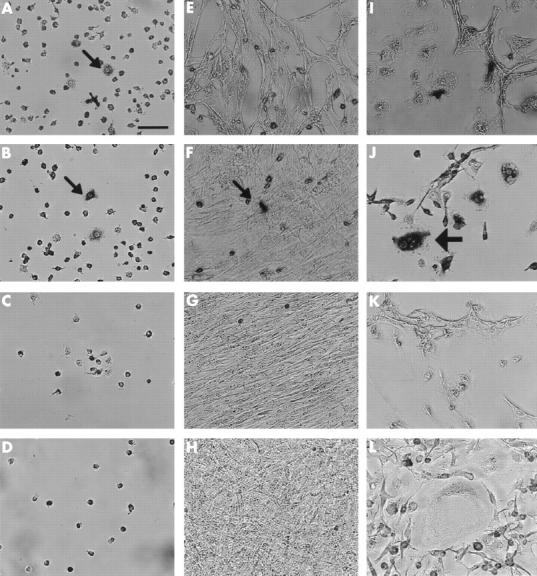

Figure 3 .

Stromal cell-like activity of granulation fibroblasts. Three different groups of cells were cultured; NA-BMCs alone (A–D), NA-BMCs and skin fibroblasts (E–H), NA-BMCs and granulation fibroblasts (I–L). This figure shows cultured cells stained by TRAP on day 2 (A, E, I), day 4 (B, F, J), day 7 (C, G, K), or day 14 (D, H, L). Bar = 10 µm. In the culture of NA-BMCs alone and NA-BMCs and skin fibroblasts, TRAP positive mononuclear cells (small arrows) survived until day 4 (A, B, F). Only in the culture of NA-BMCs and granulation fibroblasts, could we observe TRAP positive MNCs (large arrows) (J).

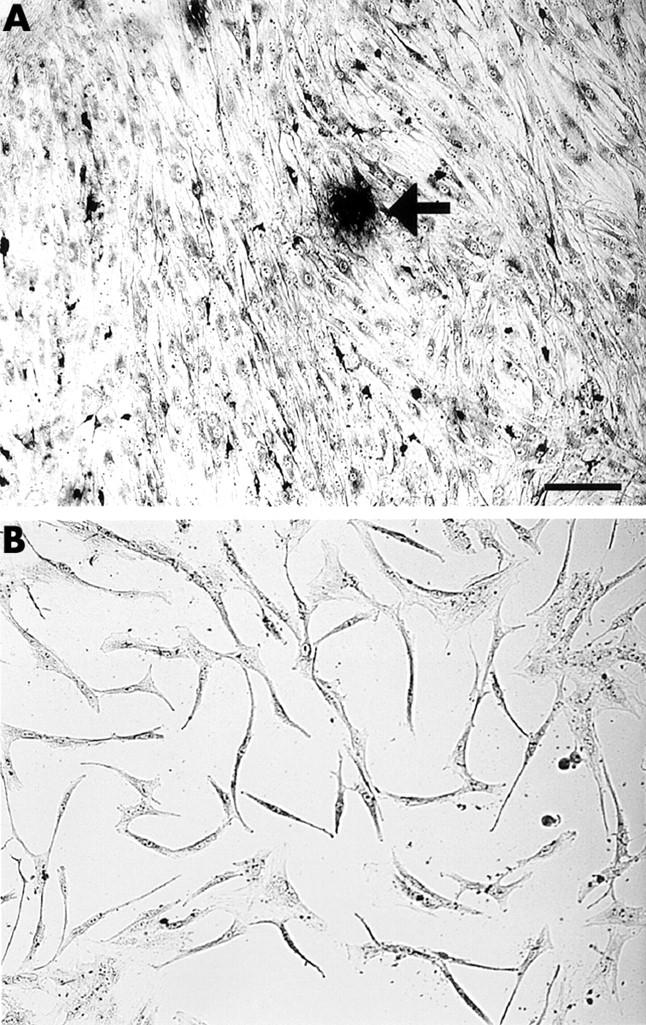

Figure 4 .

Effect of 1α,25(OH)2D3 supplementation on the number of TRAP positive MNCs. In the co-culture of NA-BMCs and granulation fibroblasts in the presence of 1α,25(OH)2D3 and ht ROSCM or in the presence of just ht ROSCM, TRAP positive MNCs appeared at two days and the number of TRAP positive MNCs increased until four days, reaching a maximum, before decreasing with time until the end of the co-culture. There was no significant difference in the number of TRAP positive MNCs (in the presence of just ht ROSCM compared with the presence of 1α,25(OH)2D3 and ht ROSCM).

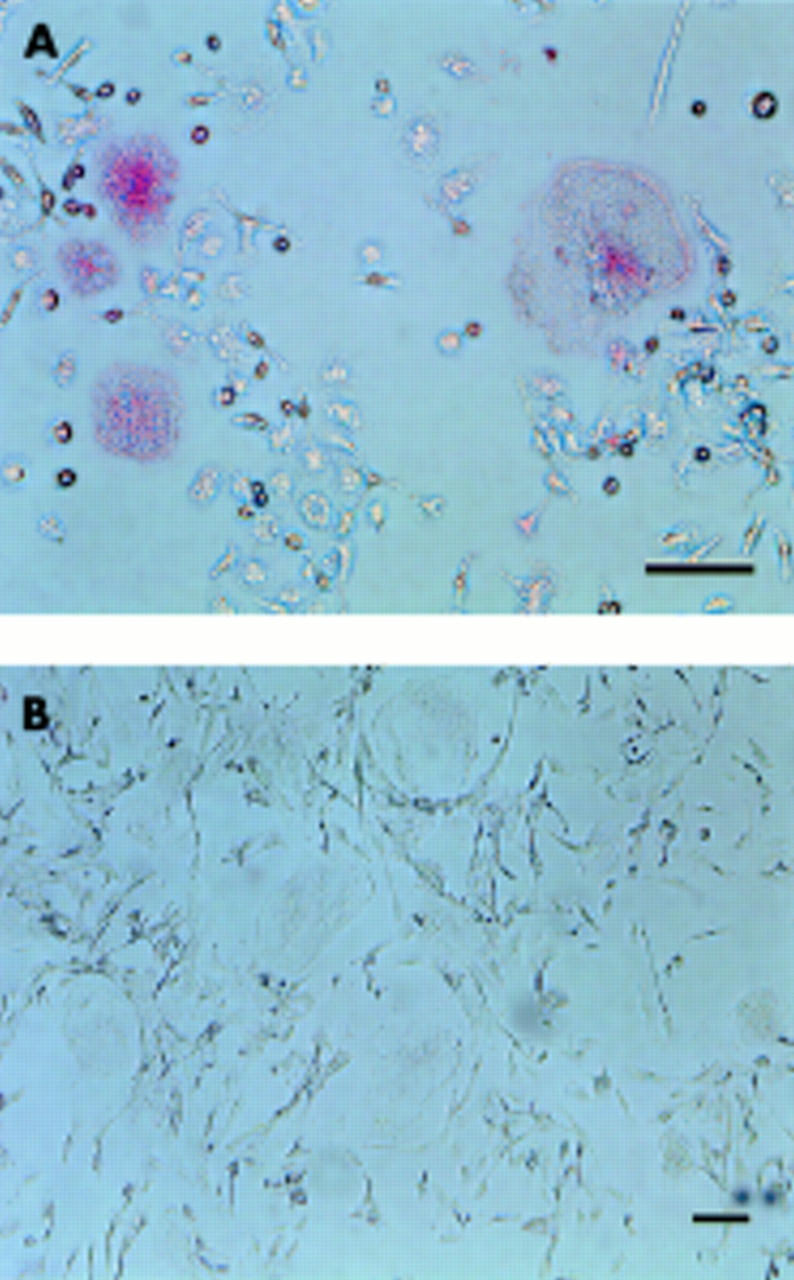

Figure 5 .

Presence of CTR on the TRAP positive MNCs formed. The cells cultured with 1α,25(OH)2D3 and ht ROSCM for four days were incubated with [125I]sCT for one hour, either without (A) or with (B) an excess amount of unlabelled sCT, followed by slight staining for TRAP. Bar = 10 µm. Grains were seen over TRAP positive MNCs (black arrow) and TRAP positive mononuclear cells (A). No grains were detected over TRAP positive MNCs or TRAP positive mononuclear cells in the same culture system when the cultured cells were incubated with an excess amount of unlabelled sCT (B).

Figure 6 .

Immunostaining by mAb Kat-1. The cultured cells (A) and human osteoclast-like cells from the giant cell tumour (B) which had been cultured for four days were stained with mAb Kat-1 followed by detection, using an ABC-AP kit. Bar = 10 µm. The MNCs formed were stained with mAb Kat-1 (A). Human osteoclast-like cells were unreactive with mAb Kat-1 (B).

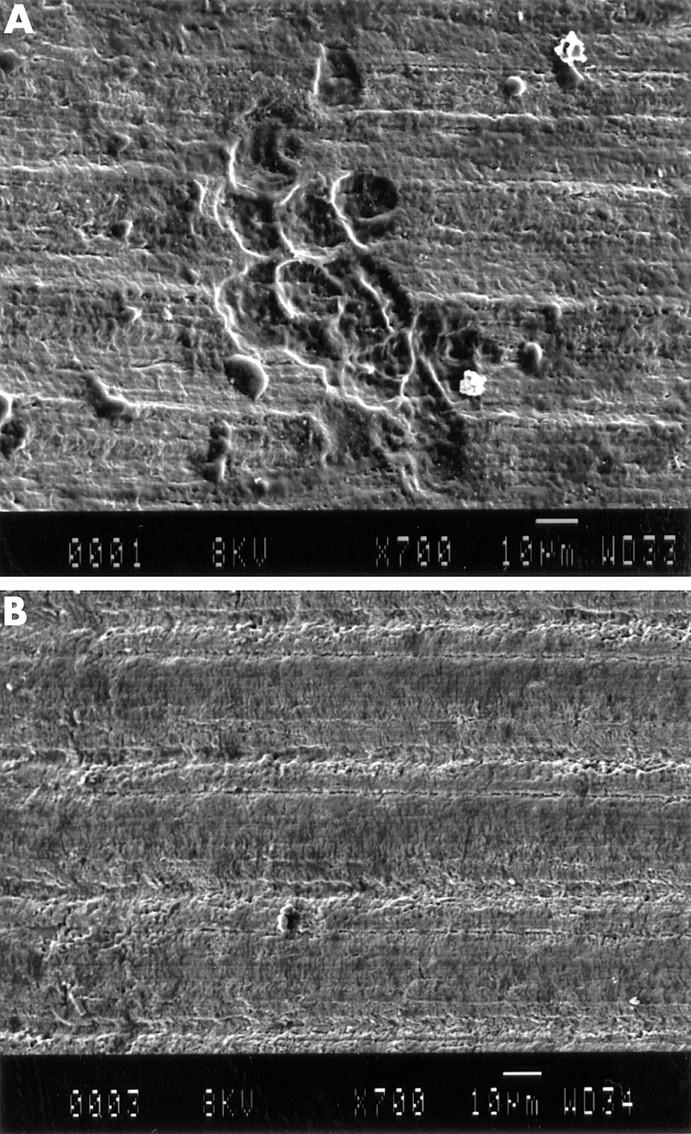

Figure 7 .

Pit formation by SEM. The cultured cells (A) and NA-BMCs alone (B) were cultured on a dentine slice for seven days. Pits were formed by the cultured cells (A). In the culture of NA-BMCs, pits were not seen (B).

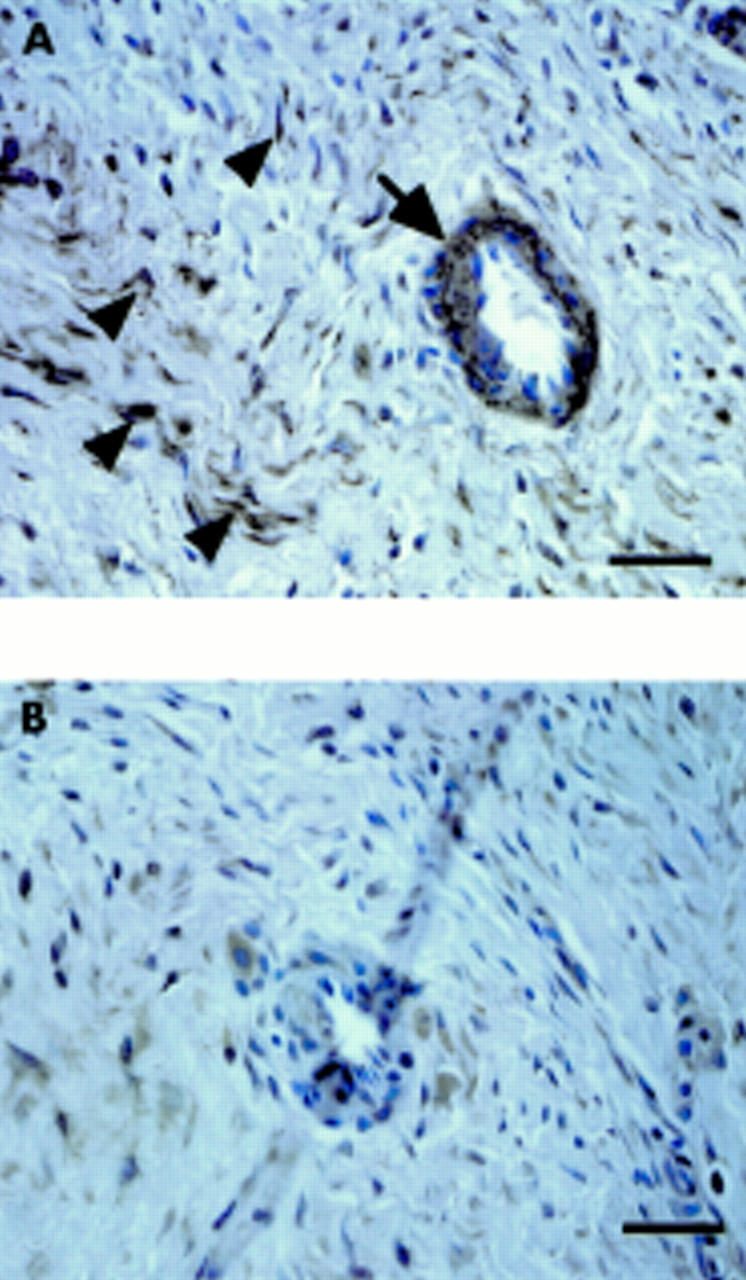

Figure 8 .

Localisation of RANKL in the granulation tissues. The granulation tissues inside the pseudocapsule were immunostained by anti-RANKL antibody (A) and control (B). Bar = 10 µm. RANKL was localised at vascular cells (arrow) and fibroblast like cells (arrow heads).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Collier F. M., Huang W. H., Holloway W. R., Hodge J. M., Gillespie M. T., Daniels L. L., Zheng M. H., Nicholson G. C. Osteoclasts from human giant cell tumors of bone lack estrogen receptors. Endocrinology. 1998 Mar;139(3):1258–1267. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.3.5825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring S. R., Jasty M., Roelke M. S., Rourke C. M., Bringhurst F. R., Harris W. H. Formation of a synovial-like membrane at the bone-cement interface. Its role in bone resorption and implant loosening after total hip replacement. Arthritis Rheum. 1986 Jul;29(7):836–842. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring S. R., Schiller A. L., Roelke M., Rourke C. M., O'Neil D. A., Harris W. H. The synovial-like membrane at the bone-cement interface in loose total hip replacements and its proposed role in bone lysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983 Jun;65(5):575–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman S. B., Chin R. C., Chiou S. S., Lee J. S. Suppression of prostaglandin E2 synthesis in the membrane surrounding particulate polymethylmethacrylate in the rabbit tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991 Oct;(271):300–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman S. B., Chin R. C., Chiou S. S., Schurman D. J., Woolson S. T., Masada M. P. A clinical-pathologic-biochemical study of the membrane surrounding loosened and nonloosened total hip arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989 Jul;(244):182–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman S. B., Chin R. C., Magee F. P. Prostaglandin E2 production by the membrane surrounding loose and fixated cemented tibial hemiarthroplasties in the rabbit knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992 Nov;(284):283–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman S. B., Davidson J. A., Song Y., Martial N., Fornasier V. L. Histomorphological reaction of bone to different concentrations of phagocytosable particles of high-density polyethylene and Ti-6Al-4V alloy in vivo. Biomaterials. 1996 Oct;17(20):1943–1947. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)00013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman S. B., Huie P., Song Y., Schurman D., Maloney W., Woolson S., Sibley R. Cellular profile and cytokine production at prosthetic interfaces. Study of tissues retrieved from revised hip and knee replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998 May;80(3):531–539. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.80b3.8158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman S. B., Lind M., Song Y., Smith R. L. In vitro, in vivo, and tissue retrieval studies on particulate debris. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998 Jul;(352):25–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itonaga I., Sabokbar A., Murray D. W., Athanasou N. A. Effect of osteoprotegerin and osteoprotegerin ligand on osteoclast formation by arthroplasty membrane derived macrophages. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000 Jan;59(1):26–31. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimi E., Nakamura I., Amano H., Taguchi Y., Tsurukai T., Tamura M., Takahashi N., Suda T. Osteoclast function is activated by osteoblastic cells through a mechanism involving cell-to-cell contact. Endocrinology. 1996 Aug;137(8):2187–2190. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.8.8754795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiranek W. A., Machado M., Jasty M., Jevsevar D., Wolfe H. J., Goldring S. R., Goldberg M. J., Harris W. H. Production of cytokines around loosened cemented acetabular components. Analysis with immunohistochemical techniques and in situ hybridization. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993 Jun;75(6):863–879. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199306000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukita A., Kukita T., Hata K., Kurisu K., Kohashi O. Heat-treated osteoblastic cell (ROS17/2.8)-conditioned medium induces the formation of osteoclast-like cells. Bone Miner. 1993 Nov;23(2):113–127. doi: 10.1016/s0169-6009(08)80048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukita A., Kukita T., Shin J. H., Kohashi O. Induction of mononuclear precursor cells with osteoclastic phenotypes in a rat bone marrow culture system depleted of stromal cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993 Nov 15;196(3):1383–1389. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukita T., Kukita A., Nagata K., Maeda H., Kurisu K., Watanabe T., Iijima T. Novel cell-surface Ag expressed on rat osteoclasts regulating the function of the calcitonin receptor. J Immunol. 1994 Dec 1;153(11):5265–5273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey D. L., Timms E., Tan H. L., Kelley M. J., Dunstan C. R., Burgess T., Elliott R., Colombero A., Elliott G., Scully S. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell. 1998 Apr 17;93(2):165–176. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder L., Lindberg L., Carlsson A. Aseptic loosening of hip prostheses. A histologic and enzyme histochemical study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983 May;(175):93–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreschini O., Fiorito S., Magrini L., Margheritini F., Romanini L. Markers of connective tissue activation in aseptic hip prosthetic loosening. J Arthroplasty. 1997 Sep;12(6):695–703. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(97)90144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray D. W., Rushton N. Macrophages stimulate bone resorption when they phagocytose particles. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990 Nov;72(6):988–992. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B6.2246303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray D. W., Rushton N. Mediators of bone resorption around implants. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992 Aug;(281):295–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey R., Quinn J. M., Sabokbar A., Athanasou N. A. Bisphosphonate inhibition of bone resorption induced by particulate biomaterial-associated macrophages. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996 Jun;67(3):221–228. doi: 10.3109/17453679608994677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey R., Quinn J., Joyner C., Murray D. W., Triffitt J. T., Athanasou N. A. Arthroplasty implant biomaterial particle associated macrophages differentiate into lacunar bone resorbing cells. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996 Jun;55(6):388–395. doi: 10.1136/ard.55.6.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollice P. F., Silverton S. F., Horowitz S. M. Polymethylmethacrylate-stimulated macrophages increase rat osteoclast precursor recruitment through their effect on osteoblasts in vitro. J Orthop Res. 1995 May;13(3):325–334. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100130305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn J. M., Athanasou N. A. Tumour infiltrating macrophages are capable of bone resorption. J Cell Sci. 1992 Mar;101(Pt 3):681–686. doi: 10.1242/jcs.101.3.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn J. M., Sabokbar A., Athanasou N. A. Cells of the mononuclear phagocyte series differentiate into osteoclastic lacunar bone resorbing cells. J Pathol. 1996 May;179(1):106–111. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199605)179:1<106::AID-PATH535>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn J., Joyner C., Triffitt J. T., Athanasou N. A. Polymethylmethacrylate-induced inflammatory macrophages resorb bone. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992 Sep;74(5):652–658. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B5.1527108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabokbar A., Fujikawa Y., Brett J., Murray D. W., Athanasou N. A. Increased osteoclastic differentiation by PMMA particle-associated macrophages. Inhibitory effect by interleukin 4 and leukemia inhibitory factor. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996 Dec;67(6):593–598. doi: 10.3109/17453679608997763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabokbar A., Fujikawa Y., Murray D. W., Athanasou N. A. Bisphosphonates in bone cement inhibit PMMA particle induced bone resorption. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998 Oct;57(10):614–618. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.10.614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabokbar A., Fujikawa Y., Murray D. W., Athanasou N. A. Radio-opaque agents in bone cement increase bone resorption. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997 Jan;79(1):129–134. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.79b1.6966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabokbar A., Fujikawa Y., Neale S., Murray D. W., Athanasou N. A. Human arthroplasty derived macrophages differentiate into osteoclastic bone resorbing cells. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997 Jul;56(7):414–420. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.7.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santavirta S., Konttinen Y. T., Bergroth V., Eskola A., Tallroth K., Lindholm T. S. Aggressive granulomatous lesions associated with hip arthroplasty. Immunopathological studies. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990 Feb;72(2):252–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santavirta S., Konttinen Y. T., Hoikka V., Eskola A. Immunopathological response to loose cementless acetabular components. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991 Jan;73(1):38–42. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B1.1991772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santavirta S., Pajamäki J., Eskola A., Konttinen Y. T., Lindholm T. Proliferative cell response to loosening of total hip replacements: a cytofluorographic cell cycle analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1991;111(1):43–46. doi: 10.1007/BF00390193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santavirta S., Xu J. W., Hietanen J., Ceponis A., Sorsa T., Kontio R., Konttinen Y. T. Activation of periprosthetic connective tissue in aseptic loosening of total hip replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998 Jul;(352):16–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuto T., Jimi E., Kukita T., Hirata M., Koga T. Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced osteoclast-like cell formation in mouse bone marrow cultures. Endocrinology. 1994 Feb;134(2):831–837. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.2.8299579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonet W. S., Lacey D. L., Dunstan C. R., Kelley M., Chang M. S., Lüthy R., Nguyen H. Q., Wooden S., Bennett L., Boone T. Osteoprotegerin: a novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell. 1997 Apr 18;89(2):309–319. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N., Akatsu T., Udagawa N., Sasaki T., Yamaguchi A., Moseley J. M., Martin T. J., Suda T. Osteoblastic cells are involved in osteoclast formation. Endocrinology. 1988 Nov;123(5):2600–2602. doi: 10.1210/endo-123-5-2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K., Iwakuma T., Harimaya K., Sato H., Iwamoto Y. EWS-Fli1 antisense oligodeoxynucleotide inhibits proliferation of human Ewing's sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor cells. J Clin Invest. 1997 Jan 15;99(2):239–247. doi: 10.1172/JCI119152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda E., Goto M., Mochizuki S., Yano K., Kobayashi F., Morinaga T., Higashio K. Isolation of a novel cytokine from human fibroblasts that specifically inhibits osteoclastogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997 May 8;234(1):137–142. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Ferguson D. J., Quinn J. M., Simpson A. H., Athanasou N. A. Biomaterial particle phagocytosis by bone-resorbing osteoclasts. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997 Sep;79(5):849–856. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.79b5.7780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Ferguson D. J., Quinn J. M., Simpson A. H., Athanasou N. A. Osteoclasts are capable of particle phagocytosis and bone resorption. J Pathol. 1997 May;182(1):92–98. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199705)182:1<92::AID-PATH813>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willert H. G., Semlitsch M. Reactions of the articular capsule to wear products of artificial joint prostheses. J Biomed Mater Res. 1977 Mar;11(2):157–164. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820110202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J., Glant T. T., Lark M. W., Mikecz K., Jacobs J. J., Hutchinson N. I., Hoerrner L. A., Kuettner K. E., Galante J. O. The potential role of fibroblasts in periprosthetic osteolysis: fibroblast response to titanium particles. J Bone Miner Res. 1995 Sep;10(9):1417–1427. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650100920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda H., Shima N., Nakagawa N., Yamaguchi K., Kinosaki M., Mochizuki S., Tomoyasu A., Yano K., Goto M., Murakami A. Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998 Mar 31;95(7):3597–3602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]