Abstract

Background: Antibodies directed to proteins containing the non-standard amino acid citrulline, are extremely specific for rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Peptidylcitrulline can be generated by post-translational conversion of arginine residues. This process, citrullination, is catalysed by a group of calcium dependent peptidylarginine deiminase (PAD) enzymes.

Objective: To investigate the expression and activity of four isotypes of PAD in peripheral blood and synovial fluid cells of patients with RA.

Results: The data presented here show that citrullination of proteins by PAD enzymes is a process regulated at three levels: transcription—in peripheral blood PAD2 and PAD4 mRNAs are expressed predominantly in monocytes; PAD4 mRNA is not detectable in macrophages, translation—translation of PAD2 mRNA is subject to differentiation stage-specific regulation by its 3' UTR, and activation—the PAD proteins are only activated when sufficient Ca2+ is available. Such high Ca2+ concentrations are normally not present in living cells. In macrophages, which are abundant in the inflamed RA synovium, vimentin is specifically citrullinated after Ca2+ influx.

Conclusion: PAD2 and PAD4 are the most likely candidate PAD isotypes for the citrullination of synovial proteins in RA. Our results indicate that citrullinated vimentin is a candidate autoantigen in RA.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (533.6 KB).

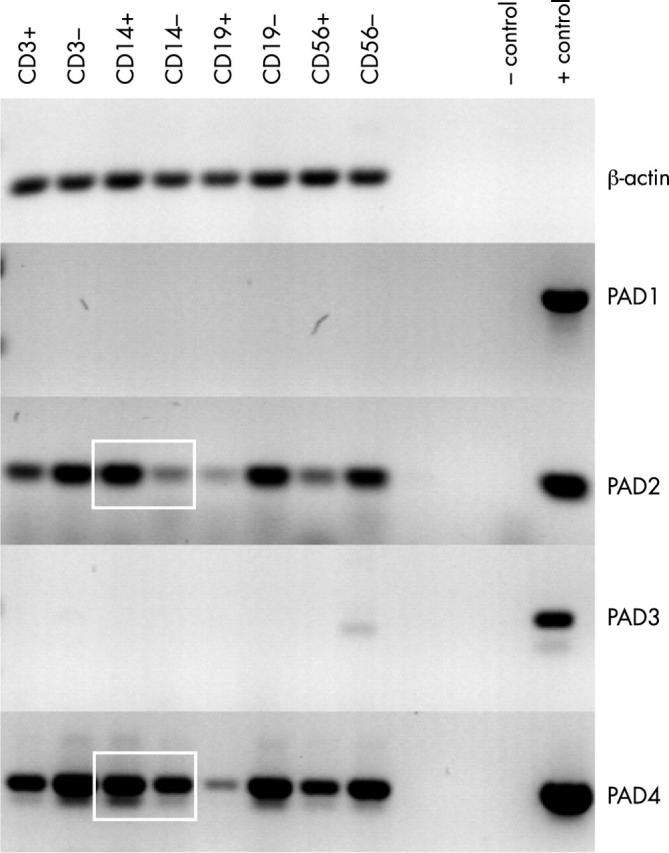

Figure 1 .

Messenger RNA expression of PAD isotypes in PBMCs. Total PBMCs from a healthy person were fractionated with MACS magnetic beads coated with either anti-CD3 (T cells), anti-CD14 (monocytes), anti-CD19 (B cells) or anti-CD56 (NK cells) for RNA isolation. Expression of PAD was analysed by RT-PCR. PAD1 and 3 were not detectable in any of the PBMC fractions. For PAD2 and PAD4, specific PCR products were produced in all fractions. In the case of CD3, CD19, and CD56, the cells that did not bind to the beads (CD3– CD19–, CD56–) showed higher expression than the cells that did bind (CD3+, CD19+, CD56+). In contrast, the cells that were bound by the anti-CD14 coated beads (CD14+, monocytes) showed higher PAD2 and PAD4 expression than the cells that did not bind the anti-CD14 coated beads (CD14–, all but the monocytes) as indicated by white squares. ß-Actin served as a control for mRNA input. Cloned cDNAs served as positive PCR controls, (no positive control included for ß-actin), PCR without template as negative control.

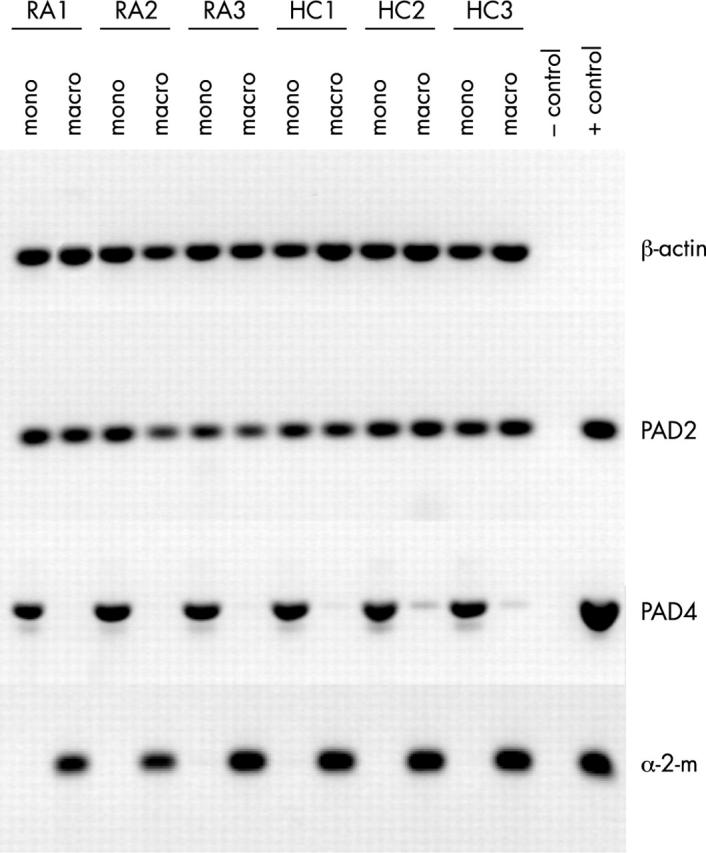

Figure 2 .

PAD4 mRNA is only expressed in monocytes, not in macrophages. RNA expression of PAD2 and PAD4 in freshly isolated monocytes (mono) from peripheral blood and in ex vivo differentiated macrophages (macro) of patients with RA (RA1–RA3) and healthy controls (HC1–HC3) was analysed by RT-PCR. ß-Actin served as a control for mRNA input, α2-macroglobulin (α-2-m) expression was analysed as a control for macrophage differentiation. Cloned cDNAs served as positive PCR controls, (no positive control included for ß-actin), PCR without template as negative control.

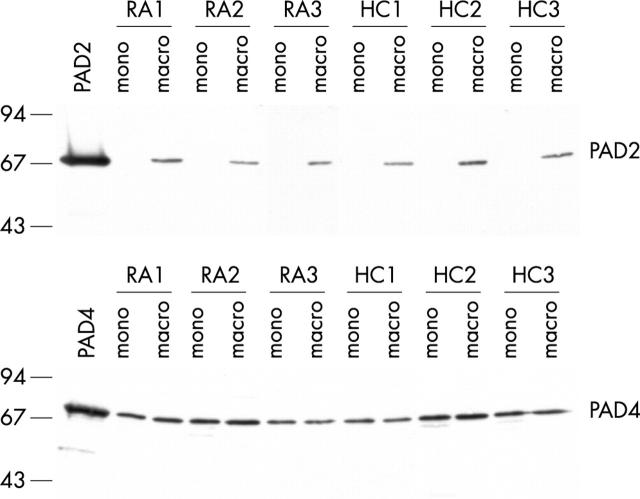

Figure 3 .

PAD2 protein is only expressed in macrophages. Protein expression of PAD2 and PAD4 in freshly isolated monocytes (mono) from peripheral blood and in ex vivo differentiated macrophages (macro) of patients with RA (RA1–RA3) and healthy controls (HC1–HC3) was analysed by western blotting. Recombinant PAD2 or PAD4 proteins are included as controls. Molecular weight markers (kDa) are indicated on the left.

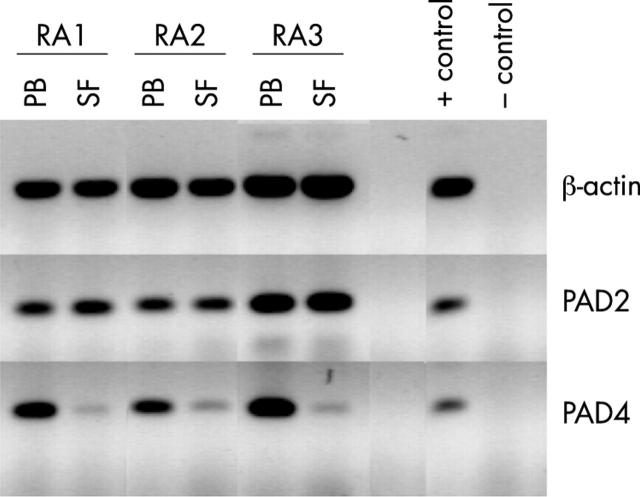

Figure 4 .

PAD4 mRNA is only present in PBMCs, not in SFMCs. Mononuclear cells were isolated from PB and SF samples of patients with RA. RNA expression of PAD2 and PAD4 was analysed by RT-PCR. ß-Actin served as a control for mRNA input. Cloned cDNAs served as positive PCR controls, (no positive control included for ß-actin), PCR without template as negative control.

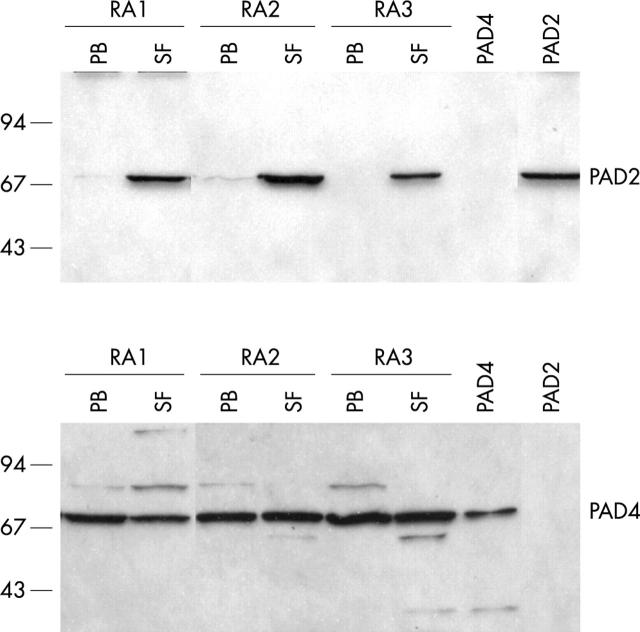

Figure 5 .

PAD2 protein is only expressed in SFMCs. Protein expression of PAD2 and PAD4 in mononuclear cells isolated from PB and SF samples of patients with RA was analysed by western blotting. Recombinant PAD2 and PAD4 proteins are included as controls. Molecular weight markers (kDa) are indicated on the left.

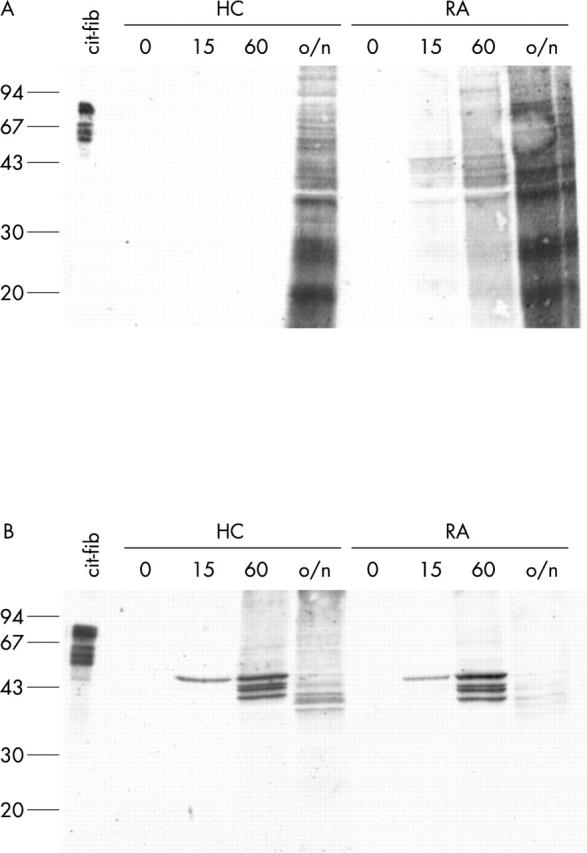

Figure 6 .

Citrullinated proteins are only generated after calcium influx. Monocytes (A) and macrophages (B) from a healthy control (HC) and a patient with RA were treated for 0, 15 minutes, 60 minutes, or overnight (o/n) with 1 µM ionomycin in the presence of 2 mM CaCl2. Extracts were analysed for the presence of citrullinated proteins by western blotting with anti-MC antibodies. In vitro citrullinated human fibrinogen (25 ng) is included as a positive control. Molecular weight markers (kDa) are indicated on the left.

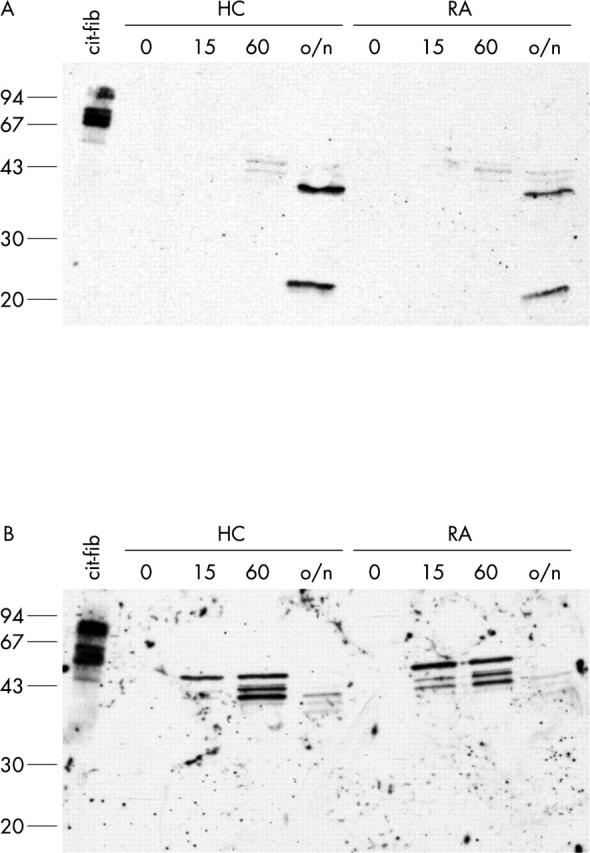

Figure 7 .

Vimentin is specifically citrullinated in calcium stimulated macrophages. Immunoprecipitated vimentin from monocytes (A) and macrophages (B) from a healthy control (HC) and a patient with RA, treated for 0, 15 minutes, 60 minutes, or overnight (o/n) with 1 µM ionomycin in the presence of 2 mM CaCl2, was stained with anti-MC antibodies. In vitro citrullinated human fibrinogen (25 ng) is included on the western blot as a positive control. Molecular weight markers (kDa) are indicated on the left.

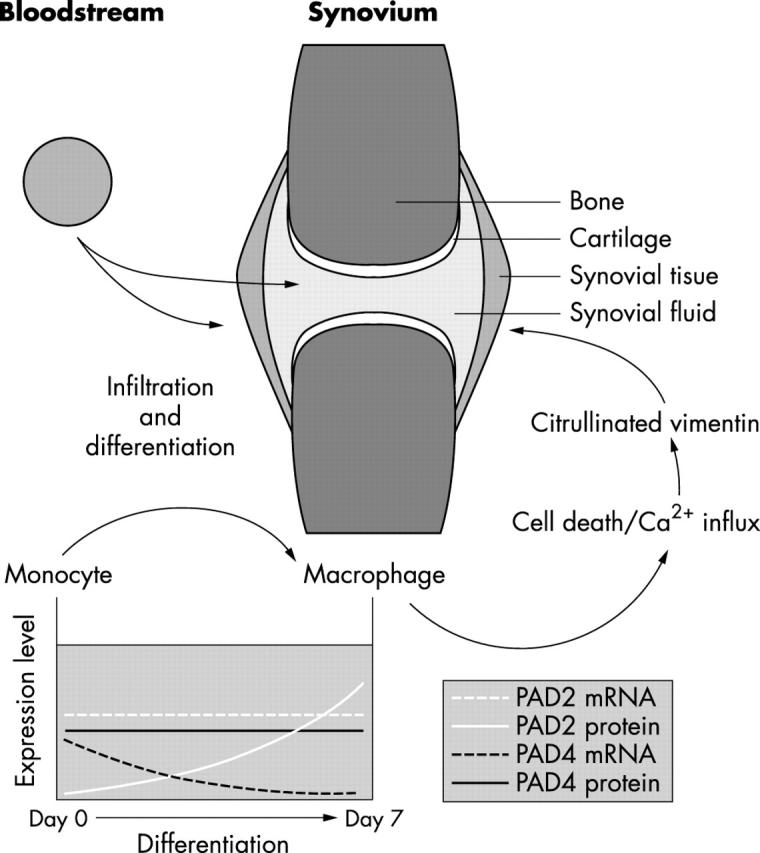

Figure 8 .

Model for synovial PAD infiltration. Many leucocytes infiltrate the inflamed synovium in RA. When monocytes from the PB enter the synovium, they will differentiate into macrophages. This differentiation process has several consequences for PAD expression: the mRNA expression of PAD4 is lost during differentiation, but the PAD4 protein levels remain unchanged, indicating that the enzyme is not rapidly degraded. For PAD2, the situation is different: the mRNA levels remain more or less the same, but the mRNA is only translated into PAD2 protein in the macrophages. The patterns of PAD expression are identical in patients with RA and healthy controls, but because of the large numbers of macrophages that can be found in the RA (and not in healthy) synovium, the amount of PAD enzyme in the RA synovium will be much higher than in healthy synovium. During apoptosis or necrosis of the PAD-containing macrophages, free intracellular Ca2+ levels are increased, resulting in activation of the PAD enzymes and citrullination of cellular proteins. In the macrophages, vimentin is specifically citrullinated after increase of cytoplasmic Ca2+. Furthermore, PAD enzymes may leak out of necrotic cells, causing the citrullination of extracellular proteins (for example, fibrin21).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Arnett F. C., Edworthy S. M., Bloch D. A., McShane D. J., Fries J. F., Cooper N. S., Healey L. A., Kaplan S. R., Liang M. H., Luthra H. S. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988 Mar;31(3):315–324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asaga H., Nakashima K., Senshu T., Ishigami A., Yamada M. Immunocytochemical localization of peptidylarginine deiminase in human eosinophils and neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol. 2001 Jul;70(1):46–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asaga H., Senshu T. Combined biochemical and immunocytochemical analyses of postmortem protein deimination in the rat spinal cord. Cell Biol Int. 1993 May;17(5):525–532. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1993.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asaga H., Yamada M., Senshu T. Selective deimination of vimentin in calcium ionophore-induced apoptosis of mouse peritoneal macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998 Feb 24;243(3):641–646. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizzaro N., Mazzanti G., Tonutti E., Villalta D., Tozzoli R. Diagnostic accuracy of the anti-citrulline antibody assay for rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Chem. 2001 Jun;47(6):1089–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byun Y., Chen F., Chang R., Trivedi M., Green K. J., Cryns V. L. Caspase cleavage of vimentin disrupts intermediate filaments and promotes apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2001 May;8(5):443–450. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L., Goodin R., Wood D., Moscarello M. A., Whitaker J. N. Rapid release and unusual stability of immunodominant peptide 45-89 from citrullinated myelin basic protein. Biochemistry. 1999 May 11;38(19):6157–6163. doi: 10.1021/bi982960s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutolo M., Sulli A., Barone A., Seriolo B., Accardo S. Macrophages, synovial tissue and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1993 May-Jun;11(3):331–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Després N., Boire G., Lopez-Longo F. J., Ménard H. A. The Sa system: a novel antigen-antibody system specific for rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1994 Jun;21(6):1027–1033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann M., Brennan F. M., Maini R. N. Rheumatoid arthritis. Cell. 1996 May 3;85(3):307–310. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrin Marina, Ishigami Akihito, Méchin Marie-Claire, Nachat Rachida, Valmary Séverine, Sebbag Mireille, Simon Michel, Senshu Tatsuo, Serre Guy. cDNA cloning, gene organization and expression analysis of human peptidylarginine deiminase type I. Biochem J. 2003 Feb 15;370(Pt 1):167–174. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara Teruki, Nakashima Katsuhiko, Hirano Hisashi, Senshu Tatsuo, Yamada Michiyuki. Deimination of arginine residues in nucleophosmin/B23 and histones in HL-60 granulocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002 Jan 25;290(3):979–983. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki M., Nishi Y., Nishizawa K., Matsuyama M., Sato C. Site-specific phosphorylation induces disassembly of vimentin filaments in vitro. Nature. 1987 Aug 13;328(6131):649–652. doi: 10.1038/328649a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki M., Takahara H., Nishi Y., Sugawara K., Sato C. Ca2+-dependent deimination-induced disassembly of intermediate filaments involves specific modification of the amino-terminal head domain. J Biol Chem. 1989 Oct 25;264(30):18119–18127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishigami Akihito, Ohsawa Takako, Asaga Hiroaki, Akiyama Kyoichi, Kuramoto Masashi, Maruyama Naoki. Human peptidylarginine deiminase type II: molecular cloning, gene organization, and expression in human skin. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002 Nov 1;407(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00516-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno T., Kawada A., Yamanouchi J., Yosida-Noro C., Yoshiki A., Shiraiwa M., Kusakabe M., Manabe M., Tezuka T., Takahara H. Human peptidylarginine deiminase type III: molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of the cDNA, properties of the recombinant enzyme, and immunohistochemical localization in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2000 Nov;115(5):813–823. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuno Reiko, Nagase Takahiro, Waki Mina, Ohara Osamu. HUGE: a database for human large proteins identified in the Kazusa cDNA sequencing project. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002 Jan 1;30(1):166–168. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroot E. J., de Jong B. A., van Leeuwen M. A., Swinkels H., van den Hoogen F. H., van't Hof M., van de Putte L. B., van Rijswijk M. H., van Venrooij W. J., van Riel P. L. The prognostic value of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000 Aug;43(8):1831–1835. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200008)43:8<1831::AID-ANR19>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisse J. R. Does rheumatoid factor always mean arthritis? Postgrad Med. 1993 Nov 1;94(6):133-4, 139. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1993.11945749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson-Bessière C., Sebbag M., Durieux J. J., Nogueira L., Vincent C., Girbal-Neuhauser E., Durroux R., Cantagrel A., Serre G. In the rheumatoid pannus, anti-filaggrin autoantibodies are produced by local plasma cells and constitute a higher proportion of IgG than in synovial fluid and serum. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000 Mar;119(3):544–552. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson-Bessière C., Sebbag M., Girbal-Neuhauser E., Nogueira L., Vincent C., Senshu T., Serre G. The major synovial targets of the rheumatoid arthritis-specific antifilaggrin autoantibodies are deiminated forms of the alpha- and beta-chains of fibrin. J Immunol. 2001 Mar 15;166(6):4177–4184. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.4177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder Barsanjit, Seshadri Vasudevan, Fox Paul L. Translational control by the 3'-UTR: the ends specify the means. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003 Feb;28(2):91–98. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer O., Labarre C., Dougados M., Goupille Ph, Cantagrel A., Dubois A., Nicaise-Roland P., Sibilia J., Combe B. Anticitrullinated protein/peptide antibody assays in early rheumatoid arthritis for predicting five year radiographic damage. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003 Feb;62(2):120–126. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.2.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi M., Manabe M., Kawamura Y., Kondo Y., Ishidoh K., Kominami E., Watanabe K., Asaga H., Senshu T., Ogawa H. Deimination of 70-kD nuclear protein during epidermal apoptotic events in vitro. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998 Nov;46(11):1303–1309. doi: 10.1177/002215549804601110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishima N. Changes in nuclear morphology during apoptosis correlate with vimentin cleavage by different caspases located either upstream or downstream of Bcl-2 action. Genes Cells. 1999 Jul;4(7):401–414. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1999.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ménard H. A., Lapointe E., Rochdi M. D., Zhou Z. J. Insights into rheumatoid arthritis derived from the Sa immune system. Arthritis Res. 2000 Aug 17;2(6):429–432. doi: 10.1186/ar122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller K., Dulku S., Hardwick S. J., Skepper J. N., Mitchinson M. J. Changes in vimentin in human macrophages during apoptosis induced by oxidised low density lipoprotein. Atherosclerosis. 2001 May;156(1):133–144. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00641-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIENHUIS R. L., MANDEMA E. A NEW SERUM FACTOR IN PATIENTS WITH RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS; THE ANTIPERINUCLEAR FACTOR. Ann Rheum Dis. 1964 Jul;23:302–305. doi: 10.1136/ard.23.4.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata S., Senshu T. Peptidylarginine deiminase in rat and mouse hemopoietic cells. Experientia. 1990 Jan 15;46(1):72–74. doi: 10.1007/BF01955420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima K., Hagiwara T., Ishigami A., Nagata S., Asaga H., Kuramoto M., Senshu T., Yamada M. Molecular characterization of peptidylarginine deiminase in HL-60 cells induced by retinoic acid and 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3). J Biol Chem. 1999 Sep 24;274(39):27786–27792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima Katsuhiko, Hagiwara Teruki, Yamada Michiyuki. Nuclear localization of peptidylarginine deiminase V and histone deimination in granulocytes. J Biol Chem. 2002 Oct 18;277(51):49562–49568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208795200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostareck D. H., Ostareck-Lederer A., Shatsky I. N., Hentze M. W. Lipoxygenase mRNA silencing in erythroid differentiation: The 3'UTR regulatory complex controls 60S ribosomal subunit joining. Cell. 2001 Jan 26;104(2):281–290. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostareck D. H., Ostareck-Lederer A., Wilm M., Thiele B. J., Mann M., Hentze M. W. mRNA silencing in erythroid differentiation: hnRNP K and hnRNP E1 regulate 15-lipoxygenase translation from the 3' end. Cell. 1997 May 16;89(4):597–606. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palosuo T., Tilvis R., Strandberg T., Aho K. Filaggrin related antibodies among the aged. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003 Mar;62(3):261–263. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.3.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reparon-Schuijt C. C., van Esch W. J., van Kooten C., Schellekens G. A., de Jong B. A., van Venrooij W. J., Breedveld F. C., Verweij C. L. Secretion of anti-citrulline-containing peptide antibody by B lymphocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001 Jan;44(1):41–47. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200101)44:1<41::AID-ANR6>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resing K. A., al-Alawi N., Blomquist C., Fleckman P., Dale B. A. Independent regulation of two cytoplasmic processing stages of the intermediate filament-associated protein filaggrin and role of Ca2+ in the second stage. J Biol Chem. 1993 Nov 25;268(33):25139–25145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodenburg R. J., Ganga A., van Lent P. L., van de Putte L. B., van Venrooij W. J. The antiinflammatory drug sulfasalazine inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha expression in macrophages by inducing apoptosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000 Sep;43(9):1941–1950. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200009)43:9<1941::AID-ANR4>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodenburg R. J., van den Hoogen F. H., van de Putte L. B., van Venrooij W. J. Peripheral blood monocytes of rheumatoid arthritis patients do not express elevated TNF alpha, IL-1beta, and IL-8 mRNA levels. A comparison of monocyte isolation procedures. J Immunol Methods. 1998 Dec 1;221(1-2):169–175. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00183-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers G., Winter B., McLaughlan C., Powell B., Nesci A. Hair follicle peptidylarginine deiminase. Exp Dermatol. 1999 Aug;8(4):362–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rus'd A. A., Ikejiri Y., Ono H., Yonekawa T., Shiraiwa M., Kawada A., Takahara H. Molecular cloning of cDNAs of mouse peptidylarginine deiminase type I, type III and type IV, and the expression pattern of type I in mouse. Eur J Biochem. 1999 Feb;259(3):660–669. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasamura Satoshi, Furukawa Ken-Ichi, Shiratori Miwa, Motomura Shigeru, Ohizumi Yasushi. Antisense-inhibition of plasma membrane Ca2+ pump induces apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2002 Oct;90(2):164–172. doi: 10.1254/jjp.90.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schellekens G. A., Visser H., de Jong B. A., van den Hoogen F. H., Hazes J. M., Breedveld F. C., van Venrooij W. J. The diagnostic properties of rheumatoid arthritis antibodies recognizing a cyclic citrullinated peptide. Arthritis Rheum. 2000 Jan;43(1):155–163. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<155::AID-ANR20>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schellekens G. A., de Jong B. A., van den Hoogen F. H., van de Putte L. B., van Venrooij W. J. Citrulline is an essential constituent of antigenic determinants recognized by rheumatoid arthritis-specific autoantibodies. J Clin Invest. 1998 Jan 1;101(1):273–281. doi: 10.1172/JCI1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab B. L., Guerini D., Didszun C., Bano D., Ferrando-May E., Fava E., Tam J., Xu D., Xanthoudakis S., Nicholson D. W. Cleavage of plasma membrane calcium pumps by caspases: a link between apoptosis and necrosis. Cell Death Differ. 2002 Aug;9(8):818–831. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebbag M., Simon M., Vincent C., Masson-Bessière C., Girbal E., Durieux J. J., Serre G. The antiperinuclear factor and the so-called antikeratin antibodies are the same rheumatoid arthritis-specific autoantibodies. J Clin Invest. 1995 Jun;95(6):2672–2679. doi: 10.1172/JCI117969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senshu T., Akiyama K., Kan S., Asaga H., Ishigami A., Manabe M. Detection of deiminated proteins in rat skin: probing with a monospecific antibody after modification of citrulline residues. J Invest Dermatol. 1995 Aug;105(2):163–169. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12317070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senshu T., Akiyama K., Nomura K. Identification of citrulline residues in the V subdomains of keratin K1 derived from the cornified layer of newborn mouse epidermis. Exp Dermatol. 1999 Oct;8(5):392–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1999.tb00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senshu T., Kan S., Ogawa H., Manabe M., Asaga H. Preferential deimination of keratin K1 and filaggrin during the terminal differentiation of human epidermis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996 Aug 23;225(3):712–719. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senshu T., Sato T., Inoue T., Akiyama K., Asaga H. Detection of citrulline residues in deiminated proteins on polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Anal Biochem. 1992 May 15;203(1):94–100. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90047-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon M., Girbal E., Sebbag M., Gomès-Daudrix V., Vincent C., Salama G., Serre G. The cytokeratin filament-aggregating protein filaggrin is the target of the so-called "antikeratin antibodies," autoantibodies specific for rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1993 Sep;92(3):1387–1393. doi: 10.1172/JCI116713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standart N., Jackson R. J. Regulation of translation by specific protein/mRNA interactions. Biochimie. 1994;76(9):867–879. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(94)90189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger K. Haploid spermatids exhibit translationally repressed mRNAs. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2001 May;203(5):323–334. doi: 10.1007/s004290100176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarcsa E., Marekov L. N., Mei G., Melino G., Lee S. C., Steinert P. M. Protein unfolding by peptidylarginine deiminase. Substrate specificity and structural relationships of the natural substrates trichohyalin and filaggrin. J Biol Chem. 1996 Nov 29;271(48):30709–30716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombal B., Denmeade S. R., Gillis J-M, Isaacs J. T. A supramicromolar elevation of intracellular free calcium ([Ca(2+)](i)) is consistently required to induce the execution phase of apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2002 May;9(5):561–573. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treiman M., Caspersen C., Christensen S. B. A tool coming of age: thapsigargin as an inhibitor of sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998 Apr;19(4):131–135. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida M., Takahara H., Minami N., Arai T., Kobayashi Y., Tsujimoto H., Fukazawa C., Sugawara K. cDNA nucleotide sequence and primary structure of mouse uterine peptidylarginine deiminase. Detection of a 3'-untranslated nucleotide sequence common to the mRNA of transiently expressed genes and rapid turnover of this enzyme's mRNA in the estrous cycle. Eur J Biochem. 1993 Aug 1;215(3):677–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urano Y., Watanabe K., Sakaki A., Arase S., Watanabe Y., Shigemi F., Takeda K., Akiyama K., Senshu T. Immunohistochemical demonstration of peptidylarginine deiminase in human sweat glands. Am J Dermatopathol. 1990 Jun;12(3):249–255. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199006000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasishta Anil. Diagnosing early-onset rheumatoid arthritis: the role of anti-CCP antibodies. Am Clin Lab. 2002 Aug-Sep;21(7):34–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vencovský J., Machácek S., Sedová L., Kafková J., Gatterová J., Pesáková V., Růzicková S. Autoantibodies can be prognostic markers of an erosive disease in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003 May;62(5):427–430. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.5.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser Henk, le Cessie Saskia, Vos Koen, Breedveld Ferdinand C., Hazes Johanna M. W. How to diagnose rheumatoid arthritis early: a prediction model for persistent (erosive) arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002 Feb;46(2):357–365. doi: 10.1002/art.10117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vossenaar Erik R., Nijenhuis Suzanne, Helsen Monique M. A., van der Heijden Annemarie, Senshu Tatsuo, van den Berg Wim B., van Venrooij Walther J., Joosten Leo A. B. Citrullination of synovial proteins in murine models of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003 Sep;48(9):2489–2500. doi: 10.1002/art.11229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vossenaar Erik R., Zendman Albert J. W., van Venrooij Walther J., Pruijn Ger J. M. PAD, a growing family of citrullinating enzymes: genes, features and involvement in disease. Bioessays. 2003 Nov;25(11):1106–1118. doi: 10.1002/bies.10357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K., Akiyama K., Hikichi K., Ohtsuka R., Okuyama A., Senshu T. Combined biochemical and immunochemical comparison of peptidylarginine deiminases present in various tissues. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988 Sep 8;966(3):375–383. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(88)90088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K., Senshu T. Isolation and characterization of cDNA clones encoding rat skeletal muscle peptidylarginine deiminase. J Biol Chem. 1989 Sep 15;264(26):15255–15260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young B. J., Mallya R. K., Leslie R. D., Clark C. J., Hamblin T. J. Anti-keratin antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. Br Med J. 1979 Jul 14;2(6182):97–99. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6182.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Boekel Martinus A. M., Vossenaar Erik R., van den Hoogen Frank H. J., van Venrooij Walther J. Autoantibody systems in rheumatoid arthritis: specificity, sensitivity and diagnostic value. Arthritis Res. 2001 Nov 6;4(2):87–93. doi: 10.1186/ar395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Venrooij W. J., Pruijn G. J. Citrullination: a small change for a protein with great consequences for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. 2000 May 24;2(4):249–251. doi: 10.1186/ar95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Venrooij W. J., Hazes J. M., Visser H. Anticitrullinated protein/peptide antibody and its role in the diagnosis and prognosis of early rheumatoid arthritis. Neth J Med. 2002 Nov;60(10):383–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]