Abstract

Objectives: To describe the impact of musculoskeletal pain (MP); to compare management of MP by the population and by primary care physicians; and to identify misconceptions about treatment.

Methods: 5803 people with MP and 1483 primary care physicians, randomly selected, in eight European countries were interviewed by telephone. A structured questionnaire was used to ask about usual management of MP and perceived benefits and risks of treatment. Current health status (SF-12) was also assessed.

Results: From primary care physicians' perceptions, MP appears to be well managed. All presenting patients are offered some form of treatment, 90% or more doctors are trying to improve patients' quality of life, and most are aware and concerned about the risks of treatment with NSAIDs. From a population perspective, up to 27% of people with pain do not seek medical help and of those who do, several wait months/years before seeing a doctor. 55% or fewer patients who have seen a doctor are currently receiving prescription treatment for their pain. Communication between doctors and patients is poor; few patients are given information about their condition; and many have misconceptions about treatment.

Conclusions: Management of MP is similar across eight European countries, but there is discordance between physician and patient perspectives of care. Some people with pain have never sought medical help despite being in constant/daily pain. Those who do seek help receive little written information or explanation and many have misperceptions about the benefits and risks of treatment that limit their ability to actively participate in decisions about their care.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (248.3 KB).

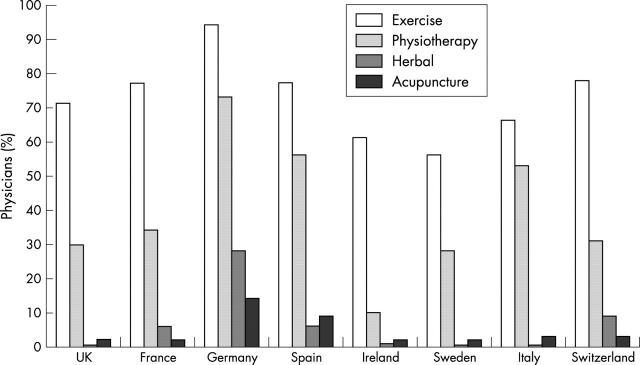

Figure 1 .

Percentage of primary care physicians in each country who recommend non-pharmacological interventions to all or most patients with MP.

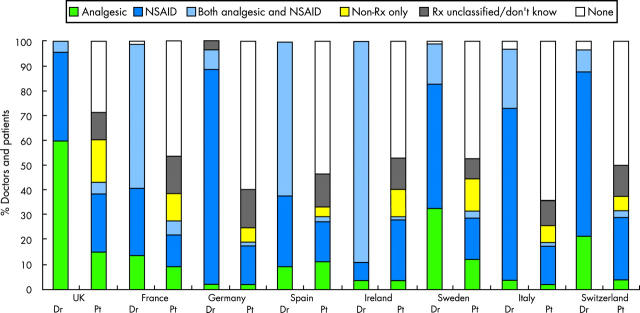

Figure 2 .

Bar chart showing drugs prescribed as first line treatment by primary care physicians and drugs currently taken by patients with MP. The physician bars (Dr) show the percentage of primary care physicians who prescribe analgesics alone, NSAIDs alone, or both NSAIDs and analgesics as first line pharmacological treatment. The patient bars (Pt) show the percentage of patients who take analgesics alone, NSAIDs alone, a combination of analgesics and NSAIDs, non-prescription (non-Rx) drugs alone, unclassified prescription drugs, or no medication.

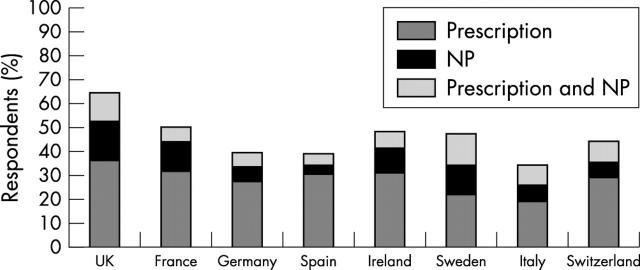

Figure 3 .

Bar chart showing the percentage of people with MP in each country who currently take drugs for pain and the type of drug taken (prescription only, non-prescription (NP), or combined prescription and NP drugs).

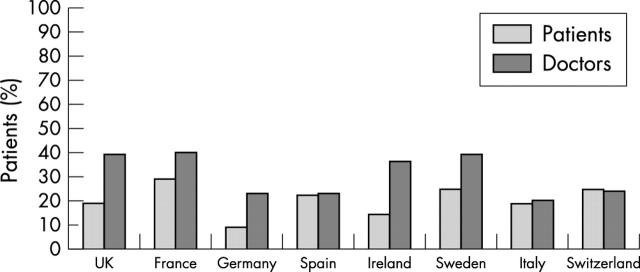

Figure 4 .

Bar chart showing the percentage of patients taking NSAIDs who think that their treatment is not at all or only a little effective in managing their pain. The doctors' data represent the percentage of patients whom primary care physicians think will require a change in their treatment because of lack of efficacy.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barlow J. H., Turner A. P., Wright C. C. A randomized controlled study of the Arthritis Self-Management Programme in the UK. Health Educ Res. 2000 Dec;15(6):665–680. doi: 10.1093/her/15.6.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker M. H., Maiman L. A. Strategies for enhancing patient compliance. J Community Health. 1980 Winter;6(2):113–135. doi: 10.1007/BF01318980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkanovic E., Hurwicz M. L., Lachenbruch P. A. Concordant and discrepant views of patients' physical functioning. Arthritis Care Res. 1995 Jun;8(2):94–101. doi: 10.1002/art.1790080207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr A. Barriers to the effectiveness of any intervention in OA. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2001 Oct;15(4):645–656. doi: 10.1053/berh.2001.0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan J. L., Blake D. R. Patient non-compliance: deviance or reasoned decision-making? Soc Sci Med. 1992 Mar;34(5):507–513. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90206-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin J. S., Black S. A., Satish S. Aging versus disease: the opinions of older black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white Americans about the causes and treatment of common medical conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999 Aug;47(8):973–979. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne R., Weinman J. Patients' beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999 Dec;47(6):555–567. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan S. H., Greenfield S., Ware J. E., Jr Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care. 1989 Mar;27(3 Suppl):S110–S127. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwoh C. K., Ibrahim S. A. Rheumatology patient and physician concordance with respect to important health and symptom status outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2001 Aug;45(4):372–377. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200108)45:4<372::AID-ART350>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwoh C. K., O'Connor G. T., Regan-Smith M. G., Olmstead E. M., Brown L. A., Burnett J. B., Hochman R. F., King K., Morgan G. J. Concordance between clinician and patient assessment of physical and mental health status. J Rheumatol. 1992 Jul;19(7):1031–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K. R., Mazonson P. D., Holman H. R. Evidence suggesting that health education for self-management in patients with chronic arthritis has sustained health benefits while reducing health care costs. Arthritis Rheum. 1993 Apr;36(4):439–446. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K. R., Sobel D. S., Stewart A. L., Brown B. W., Jr, Bandura A., Ritter P., Gonzalez V. M., Laurent D. D., Holman H. R. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Med Care. 1999 Jan;37(1):5–14. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199901000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memel D. S., Kirwan J. R., Sharp D. J., Hehir M. General practitioners miss disability and anxiety as well as depression in their patients with osteoarthritis. Br J Gen Pract. 2000 Aug;50(457):645–648. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäntyselkä P., Kumpusalo E., Ahonen R., Takala J. Patients' versus general practitioners' assessments of pain intensity in primary care patients with non-cancer pain. Br J Gen Pract. 2001 Dec;51(473):995–997. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neville C., Clarke A. E., Joseph L., Belisle P., Ferland D., Fortin P. R. Learning from discordance in patient and physician global assessments of systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity. J Rheumatol. 2000 Mar;27(3):675–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendleton A., Arden N., Dougados M., Doherty M., Bannwarth B., Bijlsma J. W., Cluzeau F., Cooper C., Dieppe P. A., Günther K. P. EULAR recommendations for the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a task force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2000 Dec;59(12):936–944. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.12.936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakalys J. A. Illness behavior in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 1997 Aug;10(4):229–237. doi: 10.1002/art.1790100404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Almazor M. E., Conner-Spady B., Kendall C. J., Russell A. S., Skeith K. Lack of congruence in the ratings of patients' health status by patients and their physicians. Med Decis Making. 2001 Mar-Apr;21(2):113–121. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0102100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J., Jr, Kosinski M., Keller S. D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996 Mar;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White K. P., Harth M. The occurrence and impact of generalized pain. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 1999 Sep;13(3):379–389. doi: 10.1053/berh.1999.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf A. D., Akesson K. Understanding the burden of musculoskeletal conditions. The burden is huge and not reflected in national health priorities. BMJ. 2001 May 5;322(7294):1079–1080. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf A. D. The bone and joint decade 2000-2010. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000 Feb;59(2):81–82. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.2.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]