Abstract

Signal transducer and activator of transcription (Stat)4 is a signaling molecule required for normal responses to interleukin-12 (IL-12) and is critically involved in inflammatory responses. We have isolated an alternatively spliced isoform of Stat4, termed Stat4β, which lacks 44 amino acids at the C-terminus, encompassing the putative transcriptional activation domain. To assess the in vivo roles of these Stat4 isoforms, we generated transgenic Stat4-deficient mice expressing Stat4α or Stat4β. Our results indicate that T-cell-specific expression of Stat4α or Stat4β can mediate many aspects of IL-12 signaling including the differentiation of Th1 cells. However, Stat4α is required for normal levels of IL-12-induced interferon-γ production from Th1 cells. Microarray analysis identified 98 genes induced by both Stat4 isoforms, 32 genes induced only by Stat4α and 29 genes induced only by Stat4β. Some induced genes correlate with specific functions including the ability of Stat4β, but not Stat4α, to mediate IL-12-stimulated proliferation. Thus, Stat4α and Stat4β have distinct roles in mediating responses to IL-12.

Keywords: IL-12/Stat4/T-helper cells/transcription

Introduction

Signal transducer and activator of transcription (Stat)4 plays a critical role in inflammatory immune responses. Stat4 is activated in response to interleukin-12 (IL-12) (Bacon et al., 1995; Jacobson et al., 1995), which promotes T-helper type 1 (Th1) cell development, interferon (IFN)-γ production and cell-mediated immune responses (Trinchieri, 1995). Gene targeting experiments have demonstrated the essential role of Stat4 in IL-12-mediated immune function (Kaplan et al., 1996; Thierfelder et al., 1996). Studies using Stat4-deficient mice have demonstrated the critical role of Stat4 in generating immune responses in inflammatory and infectious disease (Simpson et al., 1998; Holz et al., 1999; Stamm et al., 1999; Cai et al., 2000; Tarleton et al., 2000; Afanasyeva et al., 2001; Chitnis et al., 2001; Matsukawa et al., 2001; Tekkanat et al., 2001). Thus, Stat4 is a critical mediator of inflammatory responses to several cytokines.

STATs are a class of transcription factors that play a critical role in cellular growth, differentiation and immune responses. The seven STAT proteins are activated by various extracellular signals (reviewed in Darnell, 1997; O’Shea, 1997; Leonard and O’Shea, 1998). Analysis of IFN-α and IFN-γ signaling initially revealed the mechanism of STAT activation (Darnell, 1997). In unstimulated cells, STAT proteins are monomers present in the cytoplasm. After cytokine signaling and subsequent tyrosine phosphorylation of the receptor, STATs bind to the intracellular domain of the receptor and become tyrosine phosphorylated. This modification of the STATs occurs within minutes of cytokine stimulation, and begins to decline 1–2 h later. The phosphorylated STATs dimerize and then migrate to the nucleus where they regulate gene expression by binding to specific promoter elements.

Characterization of the STATs reveals several important functional domains (Darnell, 1997). The conserved N-terminal region of STATs is important for tetramer formation and cooperative DNA binding (Vinkemeier et al., 1996, 1998; Xu et al., 1996). This region has also been implicated in tyrosine phosphorylation of STATs in response to cytokine signaling (Murphy et al., 2000) and the inactivation of the tyrosine-phosphorylated Stat1 (Shuai et al., 1996). The STATs contain a novel DNA-binding domain located in the middle of the protein. The SH2 domain mediates interaction with the cytoplasmic region of cytokine receptor after ligand binding and is also required for STAT dimerization. The transcriptional activation domain of the STATs lies at the C-terminal end of the molecules (Wen et al., 1995; Mikita et al., 1996; Qureshi et al., 1996; Wang et al., 1996).

Stat1, Stat3 and Stat5 are each expressed in two alternatively spliced isoforms that vary at the C-terminal domain (Schindler et al., 1992; Schaefer et al., 1995; Wang et al., 1996, 2000). The full-length proteins are referred to as α, while the truncated forms are designated β. The β isoforms of Stat1, 3 and 5 have been shown to function as dominant-negative factors (Shuai et al., 1993; Caldenhoven et al., 1996; Wang et al., 2000). However, at some promoters, Stat3β activates transcription from composite elements in combination with c-jun and has roles distinct from those of Stat3α in vivo (Schaefer et al., 1995, 1997; Zhang et al., 1999; Yoo et al., 2002).

In this report, we show that the Stat4 gene is also expressed as an alternatively spliced isoform, Stat4β, which lacks 44 amino acids at the C-terminus. Alternatively spliced transcripts and protein for both Stat4 isoforms were detected in cell lines and primary cells. Using transgenic mice, we show that both Stat4α and Stat4β are able to activate transcription in primary cells though the isoforms have both overlapping and distinct roles in mediating the biological effects of IL-12.

Results

Isolation of Stat4β cDNA clones

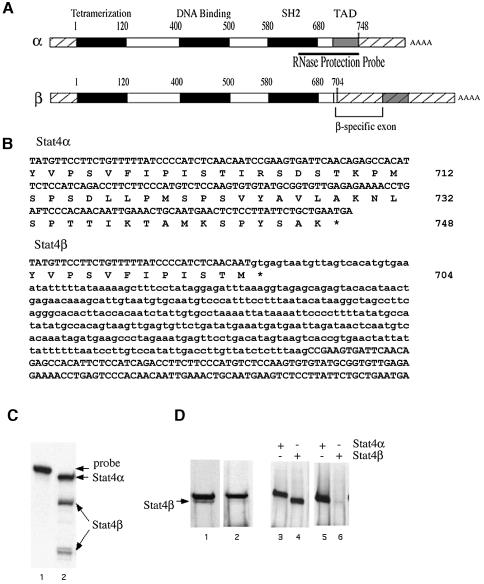

To determine whether Stat4 is expressed in different isoforms, a cDNA library prepared from human peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) was screened with a 900 bp probe derived from the 3′ end of the Stat4α cDNA. Several independent clones were isolated that contained a 369 bp insertion within the codon for amino acid 704 (Figure 1A and B). Inclusion of this sequence in the Stat4 message changes one residue and introduces a stop codon immediately downstream of the insertion point. The sequences at the borders of the Stat4β-specific region conform to the GT–AG rule for introns (Mount, 1982), indicating that this sequence corresponds to an intron that can be spliced out to generate the Stat4α isoform encoding 748 amino acids (Figure 1A and B). Inclusion of the β-specific sequence, on the other hand, generates the Stat4β isoform that encodes a protein of 704 amino acids, deleting the 44 C-terminal residues (Figure 1A and B). This cDNA clone is characteristic of a STAT β isoform because the insertion point corresponds exactly to the homologous residue in the Stat1 gene that is the site of alternative splicing for the Stat1β isoform (Yan et al., 1995).

Fig. 1. Cloning and expression of Stat4 isoforms. (A) Schematic representations of the Stat4α and Stat4β cDNAs are shown. The cross-hatched regions at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the cDNAs indicate the untranslated regions. The transcriptional activation domain (TAD) is denoted by a gray, shaded box, and the other functional domains are denoted by black regions. The numbers above the diagrams indicate the approximate positions in the amino acid sequence of the borders of these domains. The Stat4β form contains an additional exon indicated by the bracket. (B) DNA and protein sequences of the 3′ regions of the Stat4α and Stat4β cDNAs. The amino acid numbers are shown on the right. The β-specific sequence is indicated by lower case letters. Introduction of the β-specific exon introduces a stop codon, designated with an asterisk, just downstream of the splice junction at amino acid 704. (C) RNase protection was performed using a 400 nucleotide probe derived from the Stat4α cDNA (shown in A). The largest protected fragment of 400 nucleotides corresponds to the Stat4α mRNA. Hybridization to the Stat4β mRNA produces two smaller fragments of ∼260 and 140 nucleotides, corresponding to the regions upstream and downstream of the β-specific exon. (D) Nuclear extracts prepared from A139 cells were analyzed by western blot with antibodies specific for either the N- or the C-terminal regions of Stat4 (lanes 1 and 2, respectively). The specificity of the antibodies was confirmed by western blot analysis of extracts from COS cells that had been transiently transfected with Stat4α and Stat4β expression plasmids (2 µg) and immunoblotted with antibodies to the N-terminus (lanes 3 and 4) or the C-terminus (lanes 5 and 6) of Stat4. Experiments in (C) and (D) were performed at least three times.

Expression of Stat4β

RNase protection analysis demonstrated the expression of both Stat4 isoforms in A139 cells, a T-cell line expressing functional IL-12 receptors (Klein et al., 1996). The antisense RNA probe used in this assay was derived from Stat4α cDNA and spans the alternatively processed region (Figure 1A). Hybridization of the probe with RNA purified from A139 cells revealed three protected species (Figure 1C). The larger species of 400 nucleotides resulted from hybridization to Stat4α mRNA. Hybridization to the Stat4β transcript generated the two smaller fragments of ∼140 and 260 nucleotides, which correspond to the regions upstream and downstream of the β-specific exon (Figure 1A and C). This result indicates that both Stat4α and Stat4β transcripts are expressed in the A139 cell line. Similar results were obtained with human PBLs (unpublished data).

Protein expression of the Stat4 isoforms was examined by western blot analysis using nuclear extracts prepared from A139 cells. In this assay, anti-Stat4 antibodies specific for either the N-terminal region or the C-terminal domain were used. Two species of Stat4 were detected with the anti-N-terminal specific antibodies (Figure 1D, lane 1), while the anti-C-terminal specific antibodies recognized only the slower migrating species (Figure 1D, lane 2). Since the truncated Stat4β isoform would not be recognized by anti-C-terminal Stat4 antibodies, these results suggest that the slower migrating species corresponds to Stat4α while the faster migrating species corresponds to Stat4β. Expression of recombinant Stat4α and Stat4β by transient transfection in COS cells was included as a control for the specificity of the antibodies (Figure 1D, lanes 3–6). These data indicate that both Stat4 isoforms are expressed in human T cells.

Generation of Stat4α and Stat4β transgenic mice

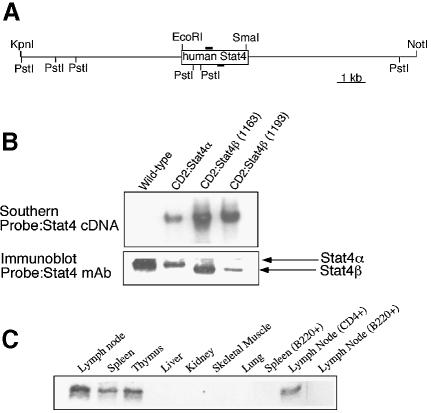

To determine the ability of Stat4β to activate gene expression in vivo, we generated transgenic mice expressing Stat4α or Stat4β cDNAs regulated by the CD2 locus control region (LCR). This expression vector directs T cell-specific expression (Zhumabekov et al., 1995). Several founders were analyzed and one Stat4α and two Stat4β transgenic lines were selected for extensive analysis. Transgene-positive mice were backcrossed with C57BL/6 Stat4-deficient mice to yield mice expressing transgenic Stat4α or Stat4β without any endogenous Stat4. Expression of transgenic Stat4α or Stat4β did not alter T-cell development as indicated by similar levels of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the thymus, spleen and lymph nodes of wild-type, Stat4–/– and Stat4α or Stat4β transgenic mice (unpublished data). Western analysis of total protein extracts from wild-type and transgenic mice examined the expression of Stat4α and Stat4β in primary T cells (Figure 2B). Importantly, the levels of Stat4α and Stat4β in the transgenic mice indicate that the proteins are not overexpressed relative to the endogenous level of Stat4. Analysis of the expression of Stat4 in transgenic mice demonstrated Stat4 in lymphoid tissues, primarily in T cells, with a much lower level of expression in B cells (Figure 2C).

Fig. 2. Generation of Stat4 transgenic mice. (A) Schematic of the Stat4 transgenic vector. (B) Expression of transgenic Stat4 was assessed by immunoblot using a monoclonal anti-Stat4. Note the slightly faster migration of Stat4β. (C) Total protein extracts from the indicated tissues from a CD2:Stat4β mouse were used for immunoblot analysis. Tissue extracts (50 µg/lane) were probed with a monoclonal anti-Stat4. Immunoblots are representative of 2–4 experiments.

Activation of Stat4 isoforms

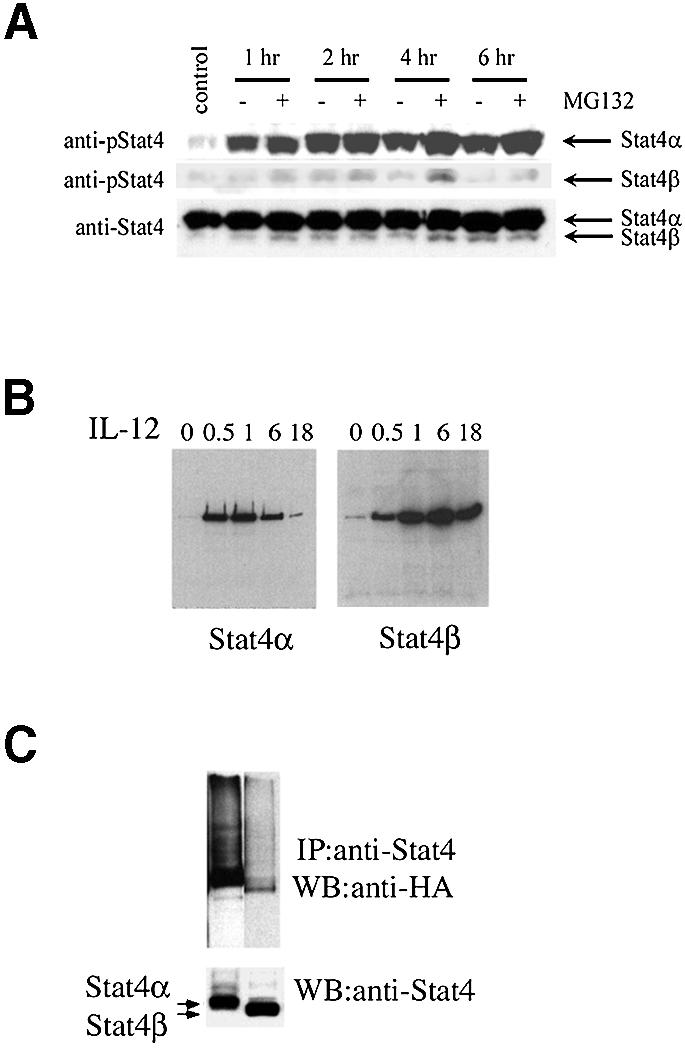

We then examined the tyrosine phosphorylation of the two isoforms following IL-12 treatment in A139 cells. In unstimulated cells, minimal tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat4 protein was observed (Figure 3A). Addition of IL-12 induced tyrosine phosphorylation of both Stat4α and Stat4β, peaking at 2 h and declining thereafter. Both Stat4 isoforms in transgenic mice were activated with kinetics similar to those seen in human cells; however, the Stat4β isoform maintained a high level of activation for a longer period of time (Figure 3B). To determine if degradation of the activated Stat4 proteins was different between the Stat4 isoforms, we treated cells with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 and examined the levels of phosphorylated Stat4. Similar to other studies (Wang et al., 2000), we found that phosphorylated Stat4 was stabilized by MG132 (Figure 3A). Interestingly, Stat4α appeared to be stabilized preferentially by proteasome inhibition while Stat4β was less affected (Figure 3A). We tested whether Stat4α or Stat4β could be ubiquitylated directly by co-transfecting Stat4 isoform-expressing plasmids with a hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged ubiquitin expression plasmid (Musti et al., 1997). Stat4α was found to be more readily ubiquitylated than Stat4β (Figure 3C). Thus, ubiquitin-mediated degradation may be one mechanism for differentially regulating Stat4 isoforms.

Fig. 3. Distinct activation kinetics of Stat4 isoforms. (A) A139 cells were incubated in the absence or presence of IL-12 (10 ng/ml) for the times indicated and in the presence or absence of 40 µM MG132 as indicated. Whole-cell extracts were prepared at the indicated time points. Extracts were resolved by SDS–PAGE, and then blotted with anti-phospho-Stat4 (upper panel). The middle panel represents a longer exposure of the upper panel to highlight Stat4β activation. The filter was then stripped and re-probed with monoclonal anti-Stat4 to demonstrate equal loading (lower panel). Results are representative of three experiments. (B) Nuclear extracts were prepared from splenocytes of Stat4 transgenic mice at the indicated times (h) after IL-12 treatment and analyzed for Stat4 DNA binding activity by DNA pull-down and western analysis. Results are representative of two experiments. (C) Ubiquitylation of Stat4α. COS7 cells were transfected with either Stat4α or Stat4β and an HA-tagged ubiquitin cloned in the pMT123 plasmid (2 µg of each plasmid). Cellular extracts harvested 48 h after transfection were immunoprecipitated with anti-Stat4 and the presence of ubiquitylated Stat4 was tested by western with anti-HA (upper panel). The same blot was stripped and re-probed with anti-Stat4 antibodies (lower panel). Data are representative of three experiments.

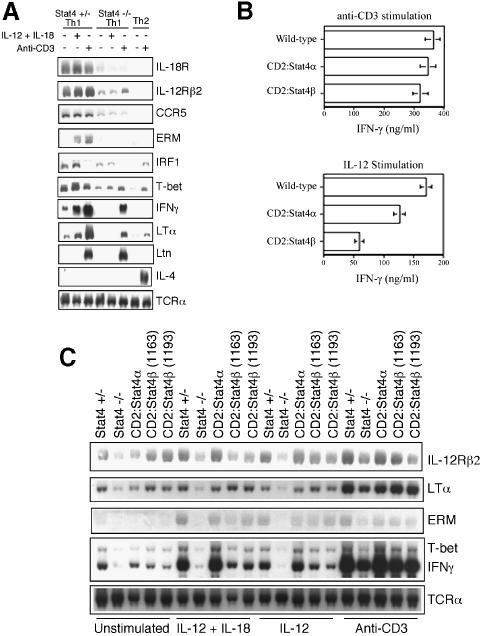

Stat4 isoform-dependent Th1 differentiation

We next wanted to examine further the ability of Stat4α and Stat4β to direct Th1 differentiation and activate IL-12-stimulated transcription in Th1 cells. To analyze gene expression, we first needed to verify target genes in the Stat4-dependent Th1 genetic program since some genes, known to be differentially expressed in Th1 versus Th2 cells, have not been carefully examined for their dependence on Stat4 in Th1 cells. Stat4 heterozygous or Stat4–/– CD4+ cells were differentiated under Th1 or Th2 conditions as indicated in Figure 4A, and either left unstimulated, or stimulated with IL-12 + IL-18 or anti-CD3 for 24 h followed by analysis of gene expression by northern blot. Expression of surface receptors including IL-18R, IL-12Rβ2 and CCR5 was greatly reduced in Stat4-deficient Th1 cultures (Lawless et al., 2000; Iwasaki et al., 2001) (Figure 4A), though expression was higher than in Th2 cells. Expression of the transcription factors ERM and T-bet was also absent or decreased in Stat4-deficient T cells, as previously observed (Ouyang et al., 1999; White et al., 2001). IFN-regulating factor-1 (IRF-1) expression was induced by IL-12 stimulation in Stat4-expressing cells, while induction was not observed in cells lacking Stat4, similar to previous reports in human cells (Coccia et al., 1999; Galon et al., 1999) (Figure 4A). IFN-γ is the hallmark cytokine secreted by Th1 cells, and its expression in response to IL-12 is known to be Stat4 dependent (Kaplan et al., 1996; Thierfelder et al., 1996; Lawless et al., 2000). In these experiments, expression of IFN-γ in response to IL-12 and IL-18 was strongly reduced in the Stat4–/– cells, while induction in Th1 polarized cells in response to anti-CD3 was also reduced, although to a lesser extent. This same pattern was observed for LTα (Figure 4A). However, not all Th1-specific genes are Stat4 dependent as we, and others, have previously demonstrated Lymphotactin (Ltn) and other genes to be expressed normally in Stat4-deficient Th1 cultures (Venkataraman et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2000b) (Figure 4A). As controls, we observed Th2-specific expression of IL-4, and equal expression of T-cell receptor (TCR) was observed in all genotypes and culture conditions. Thus, there are both Stat4-dependent and -independent aspects of the Th1 genetic program.

Fig. 4. Stat4β activates the Th1 genetic program. (A) Stat4+/– CD4+ cells were differentiated into Th1 or Th2 cells by activation with anti-CD3 in the presence of 2 ng/ml IL-12 + 10 µg/ml anti-IL-4 (Th1) or 10 ng/ml IL-4 + 10 µg/ml anti-IFN-γ (Th2). Stat4–/– CD4+ cells were differentiated into Th1 cells. After 6 days in culture, cells were left unstimulated or stimulated with 2 ng/ml IL-12 + 50 ng/ml IL-18 or 2 µg/ml plate-bound anti-CD3 for 24 h. RNA was then recovered and expression of the genes indicated was analyzed by northern blot. Results are representative of two experiments. (B) Wild-type CD2:Stat4α and CD2:Stat4β were differentiated and stimulated as in (A). Results are representative of 4–6 experiments. Supernatants were then recovered from cultures and IFN-γ levels were determined by ELISA. (C) Expression of the indicated genes was assayed by northern blot in Th1 cells derived from Stat4+/–, Stat4–/–, CD2:Stat4α and CD2:Stat4β mice. Cells were treated and RNA isolated as described in (A). Results are representative of three experiments.

To test the ability of Stat4α and Stat4β to induce Th1 differentiation, we purified CD4+ cells from wild-type, CD2:Stat4α and CD2:Stat4β mice and differentiated the cells in vitro to the Th1 phenotype by stimulating with anti-CD3 in the presence of IL-12 and anti-IL-4. After 6 days in culture, cells were washed and restimulated to examine IFN-γ production. Figure 4B demonstrates that stimulation of IFN-γ secretion in response to anti-CD3 is equivalent between wild-type and CD2:Stat4α, as previously observed (Broxmeyer et al., 2002). Importantly, IFN-γ production was comparable in CD2:Stat4β cultures following anti-CD3 stimulation. In contrast, stimulation of Th1 cultures with IL-12 demonstrated distinct functions of Stat4 isoforms. Stat4α transgenic cells secreted levels of IFN-γ comparable with control cells, while Stat4β cultures showed decreased IFN-γ secretion (Figure 4B). Thus, while both Stat4 isoforms can activate the Th1 differentiation program, they are not equivalent in direct activation of the IFN-γ gene.

To determine if other Th1-specific and Stat4-dependent genes are also expressed normally in CD2:Stat4β cells, we performed northern analysis of Th1 cultures from Stat4+/–, Stat4-deficient, CD2:Stat4α and two founder lines of CD2:Stat4β CD4+ cells left unstimulated or stimulated with IL-12 + IL-18, IL-12 alone or anti-CD3 for 24 h. Th1-specific expression of IL-12Rβ2, T-bet, ERM and LTα was observed to be similar between Stat4α- and Stat4β-expressing transgenic cells compared with Th1 cells (Figure 4C). However, IFN-γ mRNA levels were lower in cells from both Stat4β founder lines compared with either Stat4+/– or Stat4α transgenic Th1 cells (Figure 4C), which agrees with the data on IFN-γ secretion in Figure 4B. Thus, Stat4β can activate the Th1 genetic program and rescue the phenotype of Stat4-deficient Th1 cells. However, Stat4β is not as efficient as Stat4α in directly inducing IFN-γ gene expression.

Stat4 isoform-specific gene regulation

While a handful of genes have been identified as IL-12 inducible and Stat4 dependent, we wanted to determine if additional genes showed specific regulation by either Stat4α or Stat4β. Microarray analysis was performed using RNA isolated from CD2:Stat4α or CD2:Stat4β Th1 cells that were left unstimulated or stimulated with IL-12 for 18 h. Data are presented as fold induction of expression at 18 h over the expression in the unstimulated condition. Only genes that were induced >2-fold are listed. Ninety-eight genes were activated by both Stat4 isoforms (Table I). However, additional genes were induced specifically by either Stat4α (32 genes) or Stat4β (29 genes) (Tables II and III). Surprisingly, no gene expression was decreased by IL-12 treatment.

Table I. Genes induced by both Stat4α and Stat4β.

| Accession No. | Gene name | Fold induction |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stat4α | Stat4β | |||||

| Secreted factors and signal transduction | ||||||

| M32745 | TGF-β3 | 5.7 | 5.1 | |||

| AK013606 | Megakaryocyte-associated tyrosine kinase | 4.5 | 5.2 | |||

| AK008250 | Mucin 2 | 4.4 | 4.6 | |||

| AB018002 | Death-associated kinase 2 | 3.7 | 3.7 | |||

| AK017818 | RagD G protein | 3.6 | 3.7 | |||

| W74976 | Complement component 3 | 3.6 | 3.2 | |||

| AF132851 | Ras suppressor factor (RASSF) | 3.2 | 3.1 | |||

| BB264520 | JNK-interacting protein-3a (Jip3) homolog | 3.0 | 2.8 | |||

| AK005361 | Regulator of G protein signaling 16 (RGS16) | 2.9 | 2.8 | |||

| AK007774 | Latent TGF-β3-binding protein | 2.6 | 3.3 | |||

| AK018113 | Angiopoietin-related protein 2 precursor homolog | 2.6 | 2.7 | |||

| AK017187 | Serine/arginine-rich protein-specific kinase 1 (SRPK1) | 2.6 | 2.5 | |||

| AK016359 | ADP-ribosylation factor-like protein 5 (Arl5) homolog | 2.6 | 2.4 | |||

| AK010318 | Stanniocalcin 2 | 2.4 | 2.5 | |||

| AF061744 | FYN-binding protein | 2.4 | 2.5 | |||

| AK014991 | Death-associated protein 1 (DAP-1) homolog | 2.4 | 2.9 | |||

| AK002400 | ADP-ribosylation factor GTPase-activating protein 1 homolog | 2.4 | 2.4 | |||

| AF117340 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 1 | 2.4 | 2.4 | |||

| AK005456 | Tumor protein D52 | 2.3 | 2.4 | |||

| M33960 | Plasminogen activator inhibitor, type I | 2.1 | 2.0 | |||

| Cell cycle | ||||||

| AK003389 | Cyclin I | 2.6 | 2.7 | |||

| AK010928 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 | 2.6 | 2.8 | |||

| AK008585 | Cyclin ANIA-6B homolog | 2.2 | 2.2 | |||

| DNA/RNA metabolism and transcription factors | ||||||

| AK008707 | AF-9 homolog | 3.0 | 2.7 | |||

| AK011088 | G1-related zinc finger protein | 2.8 | 2.4 | |||

| AK007880 | Groucho-related protein | 2.8 | 2.7 | |||

| AK010506 | Pre-B-cell leukemia transcription factor 4 | 2.8 | 3.0 | |||

| AK004238 | Trif gene | 2.8 | 2.5 | |||

| AK017655 | Luc7 homolog | 2.7 | 2.6 | |||

| AI595019 | Suppressor of ty3 homolog (SUPT3H) homolog | 2.5 | 2.7 | |||

| AK012829 | Hypothetical nuclear factor SBBI22 (Zn finger) homolog | 2.5 | 2.9 | |||

| AK008242 | CBF1-interacting corepressor CIR homolog | 2.5 | 2.4 | |||

| AK017984 | Polycomb complex protein BMI-1 homolog | 2.4 | 2.3 | |||

| AF091234 | Btg-associated nuclear protein (BANP) | 2.2 | 2.2 | |||

| AK010477 | DNA polymerase δ smallest subunit P12 homolog | 2.1 | 2.1 | |||

| Cell surface receptors | ||||||

| AK018582 | G1-related zinc finger protein G1RP homolog sim to (GRAIL) | 4.6 | 5.4 | |||

| AK004650 | Plakophilin 2A homolog | 4.6 | 5.9 | |||

| L48015 | Activin A receptor, type II-like 1 | 4.3 | 4.3 | |||

| AK017275 | Melanoma antigen, family D, 1 | 3.7 | 4.2 | |||

| V01527 | Histocompatibility 2, class II antigen A, β1 | 3.4 | 4.0 | |||

| AK015705 | Transmembrane 4 superfamily member 9 | 3.4 | 3.4 | |||

| AF038572 | Jagged 2 | 3.1 | 3.0 | |||

| AK004539 | Receptor (calcitonin) activity-modifying protein 1 (RAMP1) | 2.7 | 3.0 | |||

| U03736 | Copper efflux ATPase homolog | 2.6 | 2.6 | |||

| AK010968 | Erythropoietin receptor | 2.6 | 2.6 | |||

| U06670 | Very low density lipoprotein receptor | 2.5 | 2.7 | |||

| L23423 | Integrin α7 | 2.5 | 2.4 | |||

| NM_010609 | Potassium channel, subfamily K, member 8 | 2.4 | 2.7 | |||

| AK010094 | Nitrophenylphosphatase homolog | 2.2 | 2.7 | |||

| L12120 | Interleukin 10 receptor α | 2.2 | 2.3 | |||

| X67469 | Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein | 2.2 | 2.2 | |||

| Vesicle formation and trafficking | ||||||

| L33726 | Fascin homolog 1 | 4.5 | 5.0 | |||

| BB222822 | Calpain 5 | 3.2 | 3.7 | |||

| AK011678 | Vesicle-associated membrane protein 4 | 2.4 | 2.8 | |||

| AK003515 | ER lumen protein-retaining receptor 2 (KDEL receptor 2) homolog | 2.4 | 2.1 | |||

| AJ272203 | Profilin 2 | 2.2 | 2.5 | |||

| AK004761 | Lysosomal apyrase-like protein (LALP70) homolog | 2.2 | 2.4 | |||

| AK011355 | Peroxisomal biogenesis factor 13 | 2.2 | 2.2 | |||

| Cellular metabolism | ||||||

| AK013167 | 1,4-α-glucan branching enzyme homolog | 4.2 | 4.8 | |||

| AK009667 | ERO1 | 4.6 | 4.7 | |||

| M74495 | Adenylosuccinate synthetase 1 | 4.0 | 3.5 | |||

| AK002783 | Acid phosphatase 6 | 3.3 | 4.0 | |||

| U16163 | Proline 4-hydroxylase, αII polypeptide | 3.7 | 3.5 | |||

| AF288783 | Glycogen phosphorylase | 3.7 | 3.3 | |||

| AK019539 | Lipin 1 | 3.3 | 3.1 | |||

| AI787918 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase homolog | 3.0 | 2.9 | |||

| NM_011961 | Procollagen lysine, 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 2 | 2.7 | 3.1 | |||

| AK012811 | F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 12 | 2.8 | 2.6 | |||

| AK012060 | Ubiquitin E3 ligase SMURF2 homolog | 2.8 | 2.6 | |||

| AK005680 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog | 2.7 | 2.5 | |||

| AK005077 | Aldolase 3, C isoform | 2.6 | 2.6 | |||

| L29123 | Ferredoxin 1 | 2.5 | 2.5 | |||

| AK012017 | Tripeptidyl peptidase II | 2.4 | 2.3 | |||

| AK004042 | Acetyl-coenzyme A synthetase 2 | 2.3 | 2.4 | |||

| AK002531 | Spermidine/spermine N1-acetyl transferase | 2.3 | 2.1 | |||

| BE573662 | Inducible 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase | 2.2 | 2.2 | |||

| Y00964 | Hexosaminidase B | 2.1 | 2.4 | |||

| Unknown | ||||||

| AK004548 | N-myc downstream regulated 1 | 3.7 | 4.0 | |||

| AK003295 | DJ434O11.1 (novel protein) homolog | 3.3 | 3.9 | |||

| AK012716 | P33ING2 homolog | 3.0 | 3.3 | |||

| AK009377 | Hypoxia-induced gene 2 | 3.0 | 2.8 | |||

| AF022992 | Period homolog | 3.0 | 3.1 | |||

| AK004851 | Gene 33 polypeptide homolog | 3.1 | 2.9 | |||

| BE573435 | Y029_human hypothetical protein KIAA0029 homolog | 3.0 | 2.9 | |||

| AK003156 | NPD017 homolog | 3.0 | 3.1 | |||

| AK009866 | PDZ domain-containing protein | 3.0 | 2.9 | |||

| AK003466 | Immediate early response 3 | 2.9 | 2.9 | |||

| AK016342 | Putative ovary-specific acidic protein homolog | 2.9 | 3.1 | |||

| AK011325 | Neighbor of A-kinase anchoring protein 95 | 2.4 | 2.1 | |||

| BE623294 | Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome candidate 1-like 1 protein homolog | 2.4 | 2.2 | |||

| AK017846 | PR-domain-containing protein 16 homolog | 2.3 | 2.6 | |||

| AK013649 | HDCMC04P homolog | 2.3 | 2.4 | |||

| AK003918 | Reticulocabin precursor homolog | 2.3 | 2.5 | |||

| AK018058 | BM024 homolog | 2.3 | 2.2 | |||

| AK014511 | RIS homolog | 2.2 | 2.9 | |||

| AW113965 | Z73359 human DNA homolog | 2.2 | 2.3 | |||

| AK014585 | SAD1 UNC-84 domain protein 1 homolog | 2.2 | 2.2 | |||

| AK014600 | Immunoglobulin domain-containing protein | 2.1 | 2.2 | |||

RNA from CD2:Stat4α or CD2:Stat4β Th1 cells was stimulated with or without IL-12 for 18 h. Fold induction is the expression at 18 h divided by expression in unstimulated cells and is the average of duplicate determinations. Average fold variation between the determinations was 0.23.

Table II. Genes induced specifically by Stat4α.

| Accession No. | Gene name | Fold induction |

|---|---|---|

| Secreted factors and signal transduction | ||

| S37052 | Vascular endothelial growth factor-3 | 2.6 |

| AK017251 | TBC domain-containing protein | 2.3 |

| AW318679 | MEK binding partner 1 | 2.1 |

| AW536752 | SH3-domain-binding protein 4 homolog | 2.1 |

| Cell cycle | ||

| AK004705 | RGC32, induced by complement activation in oligodendrocytes homolog | 2.2 |

| U10440 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (p27Kip1) | 2.2 |

| DNA/RNA metabolism and transcription factors | ||

| AK011431 | H3 histone, family 3B | 3.0 |

| AK002725 | Histone gene complex 2 | 2.6 |

| AK011560 | Histone 4 protein | 2.6 |

| AK011843 | RNA polymerase II | 2.4 |

| AK002387 | Zinc/ring finger, C3HC4 type-containing protein | 2.3 |

| AK009842 | Zinc finger protein 94 (ZFP-94) homolog | 2.3 |

| AK003001 | Activating transcription factor 4 (ATF-4) | 2.2 |

| AW681680 | Putative RNA helicase homolog | 2.2 |

| BE289038 | RelA-associated inhibitor homolog | 2.2 |

| AI385616 | Nuclear receptor ROR-α-1 homolog | 2.1 |

| AK012632 | Splicing factor 3b, subunit 1 | 2.0 |

| Cell surface receptors | ||

| AK019083 | Receptor (calcitonin) activity-modifying protein 2 | 2.3 |

| Cellular metabolism | ||

| AK002447 | Selenium-binding protein 1 | 7.4 |

| M75135 | Solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transporter), member 3 | 2.6 |

| M35021 | Heat shock protein, 70 kDa 1 | 2.5 |

| AK002455 | Acid sphingomyelinase-like phosphodiesterase 3a | 2.5 |

| AK003051 | Enolase 2, γ neuronal | 2.4 |

| AF045573 | Leucine-rich repeat (in FLII)-interacting protein 1 | 2.3 |

| AK009422 | 5-Formyltetrahydrofolate cyclo-ligase homolog | 2.2 |

| AK016474 | Autophagy 12 (APG12) homolog | 2.1 |

| AK003223 | Dolichol-phosphate-mannose synthase homolog | 2.1 |

| AF221525 | Cytochrome P450 | 2.1 |

| AI429813 | GTP-binding protein and M protein homolog | 2.0 |

| AK005798 | GAPDH homolog | 2.0 |

| Unknown | ||

| AK002594 | HSPC189 protein homolog | 2.3 |

| AK008415 | Protein X 013 homolog | 2.2 |

Table III. Genes induced specifically by Stat4β.

| Accession No. | Gene name | Fold induction |

|---|---|---|

| Secreted factors and signal transduction | ||

| AB041542 | Hypothetical serine/threonine protein kinase | 3.0 |

| AK004590 | SH3-domain GRB2-like B1 (endophilin) | 2.6 |

| Y17860 | Ganglioside-induced differentiation-associated-protein 10 | 2.2 |

| AF020526 | SH2-B PH domain-containing signaling mediator 1 | 2.1 |

| X95603 | Insulin-like 3 | 2.1 |

| AA475831 | Centaurin β1 homolog | 2.0 |

| DNA/RNA metabolism and transcription factors | ||

| Y14296 | Kruppel-like factor 9 | 2.3 |

| AK007317 | Host cell factor C1 (HCF) homolog | 2.2 |

| AK002324 | P34SEI-1/TRIP-Br1 | 2.2 |

| AK013443 | Hairy and enhancer of split 6 (Drosophila) | 2.1 |

| AK007492 | Transcription initiation factor IIE, β subunit (TFIIE-BETA) | 2.1 |

| Cell surface receptors | ||

| AK010239 | Frizzled homolog 7 (Drosophila) | 2.8 |

| C88843 | Kidney injury molecule-1 homolog | 2.1 |

| AK002332 | Basigin/CD147 | 2.1 |

| Vesicle formation and trafficking | ||

| AK010786 | Tubulin β chain (T BETA-15) homolog | 2.8 |

| M11686 | Keratin complex 1, acidic, gene 18 | 2.6 |

| AK003049 | Secretory granule neuroendocrine protein 1 | 2.5 |

| AK014595 | Coatomer protein complex, subunit γ1 | 2.3 |

| U58869 | Pantophysin | 2.2 |

| AK009735 | Adaptor protein complex AP-2, α2 subunit | 2.1 |

| Cellular metabolism | ||

| AK007983 | Metallothionein 1 | 3.3 |

| AK009903 | Aspartate-β-hydroxylase | 2.4 |

| AK003332 | Peroxiredoxin 6 | 2.3 |

| AK003930 | Serine (or cysteine) proteinase inhibitor | 2.1 |

| AF004106 | Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 | 2.1 |

| AK002740 | Voltage-dependent anion channel 1 | 2.1 |

| AI317339 | Inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain precursor homolog | 2.1 |

| AK012352 | Nucleoredoxin | 2.0 |

| Unknown | ||

| AK019405 | ALEX1 protein homolog | 2.2 |

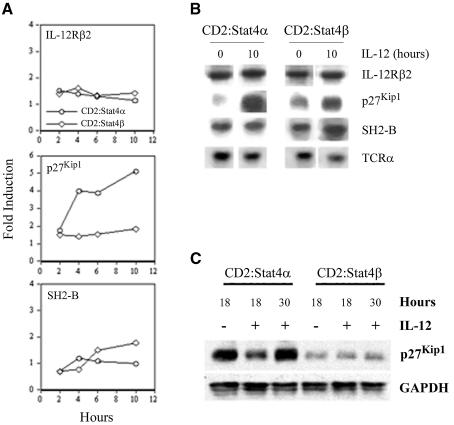

To verify these targets as IL-12-responsive genes and as differential targets of Stat4α and Stat4β, we performed northern analysis of RNA isolated from IL-12-stimulated activated T cells at several time points. We first examined induction of IL-12Rβ2, since it was expressed equally in Stat4α and Stat4β transgenic Th1 cells (Figure 4C). As previously observed (Lawless et al., 2000), there is a 1.5- to 2-fold induction of IL-12Rβ2 mRNA following IL-12 stimulation, and this induction is similar between Stat4α- and Stat4β-expressing cells (Figure 5A and B). The cell cycle inhibitor, p27Kip1, was shown to be activated specifically by Stat4α (Table II). Northern and western analysis confirmed this, showing an almost 5-fold induction over 10 h in Stat4α-expressing cells, with little induction in Stat4β-expressing cells (Figure 5A–C). Decreased p27Kip1 levels even in unstimulated CD2:Stat4β cells is reflected in the enhanced growth characteristics of these cells. In contrast, the SH2-B gene is induced 2-fold by 10 h in Stat4β-expressing cells, while it is not induced in Stat4α-expressing cells (Figure 5A and B).

Fig. 5. Differential gene activation by Stat4 isoforms. (A) Spleen cells CD2:Stat4α or CD2:Stat4β were activated with anti-CD3 for 72 h. Cells were then washed and incubated for the indicated time periods with 2 ng/ml IL-12. RNA was isolated, electrophoresed and transferred to nylon membrane. Membranes were hybridized sequentially with radiolabeled IL-12Rβ2, p27Kip1 and SH2-B cDNAs. The blot was stripped and re-probed with TCRα as a control for loading. Densitometry was performed following autoradiography, and expression was normalized to TCRα expression and is presented as the fold induction over expression of the genes in unstimulated cells. Results are representative of several different northern analyses. (B) Autoradiographs of northern analysis of the induction of genes analyzed in (A). (C) Western analysis of p27Kip1 levels in Stat4α and Stat4β transgenic Th1 cells. Protein extracts from cells incubated with or without 2 ng/ml IL-12 for the indicated times were resolved by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with monoclonal anti-p27Kip1 followed by stripping and probing with anti-GAPDH as a loading control. Results are representative of two experiments.

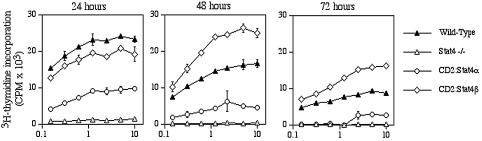

We have shown previously that p27Kip1 regulates cytokine-stimulated proliferation and that p27Kip1 deficiency partially rescues the inability of Stat4-deficient activated T cells to proliferate (Zhang et al., 2000a; Shen and Kaplan, 2002). Thus, if p27Kip1 is induced by Stat4α, but not Stat4β, we would expect that there would be differences in their proliferative responses to IL-12. To test this, wild-type, Stat4-deficient, CD2:Stat4α and CD2:Stat4β Th1 cells cultured as described above were stimulated with increasing doses of IL-12 and pulsed with tritiated thymidine at various time points. Cultures harvested at 24 h demonstrated similar proliferation between wild-type and Stat4β cells, while Stat4α cells showed considerably lower levels of proliferation and Stat4-deficient cells had a minimal proliferative response. Wild-type cell proliferation decreased at the 48 and 72 h time points, while, comparatively, Stat4β cells showed enhanced proliferation at these time points. Stat4α-expressing cells consistently showed diminished proliferative responses compared with wild-type or Stat4β-expressing cells. Thus, Stat4α-expressing cells, which induce p27Kip1 expression, demonstrate modest IL-12 proliferative responses. These results suggest that Stat4β is required for a normal proliferative response to IL-12.

Discussion

In this report, we have demonstrated that the Stat4 gene encodes a truncated isoform, Stat4β, which is created by alternative mRNA splicing. Thus, Stat4 is similar to STATs 1, 3, 5A and 5B in that it is expressed as an isoform that lacks the C-terminal domain. This region has been shown to be critical for transcriptional activation by Stat1 and Stat5. The Stat1β and Stat5β isoforms, which lack this C-terminal region, exhibit different transcriptional activities from their full-length α isoforms. Stat1β cannot mediate IFN-γ control of cell growth (Bromberg et al., 1996) and failed to promote the transcription of an IFN-γ-inducible reporter gene (Wen et al., 1995). Similarly, Stat5β isoforms act as dominant-negative factors to suppress genes that are normally activated by Stat5A (Wang et al., 1996). Based on these precedents, we expected that Stat4β might also function as a dominant-negative repressor of transcription. However, studies using transgenic mice that express either Stat4α or Stat4β demonstrate that Stat4β can activate many IL-12-inducible genes. Furthermore, there are distinct requirements for both isoforms of Stat4. For example, Stat4α is required for maximal induction of IL-12-induced IFN-γ production, while Stat4β is required for IL-12-stimulated proliferative responses.

The C-terminal ‘transactivation’ domain of Stat4 can activate transcription in a GAL4 fusion reporter assay (unpublished data), though only to a very low level. Thus, the mechanism for Stat4β-dependent gene transactivation is still unclear. Studies using a reporter with the Stat4-inducible element of the IRF-1 promoter (Coccia et al., 1999; Galon et al., 1999) demonstrate the importance of the adjacent CRE site and suggest that interactions with, or recruitment of, Jun or ATF family members at IL-12-inducible promoters may be important in mediating robust transcriptional activation (unpublished data). This is very similar to the mechanism of transcriptional activation by Stat3β, which interacts with Jun family members through the STAT N-terminal coiled-coil region (Schaefer et al., 1995, 1997; Zhang et al., 1999). Importantly, the biological effects of Stat4 are not mediated by heterodimerization with other STAT family members (unpublished data).

IL-12 has also been reported to activate p38 MAPK (Visconti et al., 2000; Zhang and Kaplan, 2000), which is involved in the phosphorylation of Stat4 Ser721, contained in the transactivation domain, to increase Stat4-dependent transactivation. Mutation of Ser721 reduced IL-12-dependent activation of a reporter gene in a transient transfection assay in Jurkat cells (Visconti et al., 2000). Reconstitution of Stat4 S721A into Stat4-deficient T cells recovered IL-12-stimulated proliferative responses but not IL-12-stimulated IFN-γ production or Th1 differentiation (Morinobu et al., 2002). The reliance on Ser721 phosphorylation for IFN-γ production agrees with our own data that the Stat4 C-terminal domain is required for IL-12-induced IFN-γ production (Figure 4). However, we observed normal Th1 differentiation, as assessed by anti-CD3-induced IFN-γ production as well as several other genes, in Stat4β transgenic mice. This differed from the result in Morinobu et al. (2002) that demonstrated little Th1 differentiation in Stat4 S721A-reconstituted Stat4-deficient cells. These data suggest that Stat4β and Stat4 S721A are not functionally equivalent and that the S721A mutation might even interfere with the ability of Stat4 to interact with other proteins to mediate transactivation, thus functioning as a dominant negative at some gene promoters. It may be interesting to compare these forms of Stat4 directly in the future.

There may be important differences in the activation of the Stat4 isoforms. In transgenic mice, Stat4β stays activated for a longer period of time than Stat4α, though this difference is not as clear in a human cell line. Consistent with this observation, the β isoforms of other STATs have been reported to remain activated longer than the α forms following tyrosine phosphorylation (Wang et al., 1996, 2000; Park et al., 2000). This may also result in altered DNA binding, since the β isoform of Stat3 forms more stable dimers resulting in enhanced DNA binding affinity (Park et al., 2000). The mechanism of the altered activation kinetics between the Stat4 isoforms is still unclear and may also be distinct in human and mouse cells. It may be due to the fact that Stat4α is more extensively ubiquitylated and sensitive to proteasome inhibition than Stat4β, allowing greater Stat4β accumulation within the cell (Figure 3). Alternatively, it could be a product of a unique biological function. For example, Stat4β, but not Stat4α, activates the expression of SH2-B (Figure 5), which has been shown to potentiate Janus kinase activation (Rui and Carter-Su, 1999; O’Brien et al., 2002). Altered kinetics could also be a result of differential inhibitor function such as altered SOCS activation or decreased interaction with a STAT phosphatase. The mechanism of altered activation of Stat4 isoforms may involve several of these possibilities, and more detailed experimentation will be required.

It is also interesting to speculate on the unique roles that each Stat4 isoform may have in vivo. While we have shown that there are functional differences between the isoforms in mice that express only one isoform, the regulation of genes and biological responses in cells that express both isoforms will be more complex. Stat4α is far more abundant than Stat4β, and has the property of being transiently activated. In contrast, Stat4β maintains activation for a longer period of time and may bind DNA more tightly, as discussed above. Thus, gene activation may be more Stat4α dependent at early time points, while Stat4β may be critical for sustained gene expression. Further analysis of gene induction kinetics in Stat4 isoform-expressing transgenic mice may help distinguish the roles of Stat4α and Stat4β in IL-12 responses.

Our analysis of the Stat4-activated transcriptome demonstrated both common and distinct roles for Stat4α and Stat4β in activating gene transcription (Tables I–III). Stat4α induces genes that interfere with the cell’s ability to proliferate, as we demonstrated in Figures 5 and 6. Stat4α also induces a splicing factor that might play a role in enhancing Stat4β production. Stat4β activates a panel of genes involved in vesicle formation that might increase secretion of cytokines or other regulatory factors. Stat4β also activates a distinct set of surface proteins that play a role in adhesion and inflammation. Biologically, we have shown that Stat4α is required for maximal IL-12-induced IFN-γ production, while Stat4β is required for normal IL-12-stimulated proliferative responses. Both isoforms mediate the induction of several IL-12-responsive genes as well as promoting Th1 differentiation. Thus, while Stat4 isoforms may have overlapping functions, each isoform is required for specific subsets of IL-12-stimulated biological responses. Furthermore, IL-23- or IFN-α-stimulated Stat4 activity (Cho et al., 1996; Oppmann et al., 2000; Nguyen et al., 2002) may reveal further distinct roles for each isoform. As the functions of more genes are identified, the unique roles that Stat4α and Stat4β play in the inflammatory response will become clearer.

Fig. 6. Differential requirements for Stat4 isoforms in IL-12-stimulated proliferation. Th1 cells from mice of the indicated genotypes were generated as described in Figure 5. Cells were plated in microtiter plates with the indicated concentration of IL-12 and in the presence of 5 µg/ml anti-IL-2. Cultures were pulsed with [3H]thymidine for the last 18 h of 24, 48 and 72 h time points. Cultures were then harvested and counted in a scintillation counter. Results are representative of at least six experiments with both activated T and Th1 cells.

Alternative splicing of STAT mRNAs appears to be a common mechanism to increase the diversity of gene regulation in response to cytokine signaling. Our results suggest that alternatively spliced forms of Stat4 regulate cytokine responses during T-cell activation and differentiation. Identification of more IL-12-inducible genes and characterization of their promoters will yield further insights into the mechanisms of Stat4 transcriptional activity.

Materials and methods

Isolation of a Stat4β cDNA clone

A randomly primed cDNA library derived from human PBLs was screened with a 900 bp probe from the 3′ end of the Stat4α cDNA. Construction of the library and conditions for hybridization and washing have been described previously (Hoey et al., 1995). Thirty-two positive clones were obtained from ∼1 × 106 recombinant phage. These clones were analyzed by DNA sequencing: 27 were identical to Stat4α, and five contained an insertion of 369 bp not present within the Stat4α clone. cDNAs encoding Stat4α and Stat4β were cloned into the pRK5 expression vector, which contains a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter and an N-terminal myc epitope.

Cell culture

COS7 cells were grown in Dulbeccos’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% fetal calf serum. A139 cells were grown in AIM-V/RPMI (1:1) + 10% serum + 10 ng/ml IL-2. Before stimulating A139 cells with IL-12, the cells were washed with acidic RPMI pH 6.4 and starved in RPMI + 2% serum for 6 h. Human PBLs were grown in RPMI + 10% serum + 2.5 µg/ml phytohemagglutinin-L (PHA; Boehringer-Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN).

RNase protection assay

Total RNA was prepared from A139 cells or human PBLs using the Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). The RNase protection assay was performed with 20 µg of total RNA as previously described (Williams et al., 1988). Antisense RNA probes for human Stat4 were synthesized with either T7 or T3 RNA polymerase and radiolabeled with [α-32P]CTP (Dupont). The labeled RNA probes were gel purified on a 6% polyacrylamide denaturing gel.

Immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis

Nuclear extracts from A139 and Stat4-transfected COS7 (2 µg of the indicated plasmid using calcium phosphate precipitation) cells were prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-Stat4 antiserum for 2 h at 4°C and then mixed with protein A–Sepharose beads (Pharmacia) for 1 h at 4°C. The samples were washed five times with 1 ml of TNT (200 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1% Triton) buffer containing phosphatase inhibitors (1 mM NaVO4 and 5 mM NaF) and Complete® (Boehringer Mannheim) protease inhibitor tablets. Immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by 7.5% SDS–PAGE and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore). Membranes were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and sequentially incubated with anti-phosphotyrosine (1:1000) or anti-STAT4 antibodies (1:1000) followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (1:5000, Amersham). Proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham). Mouse anti-phosphotyrosine antibody was purchased from Zymed Laboratories Inc. (PY-7E1). Anti-Stat4 antibodies were generated in rabbits by using purified, full-length Stat4α as the antigen. These antibodies recognize both Stat4α and Stat4β. In addition, anti-peptide antibodies specific against the N- (L18) and C-terminus (C20) of Stat4 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Generation of transgenic mice

The generation of Stat4-deficient mice has been described previously (Kaplan et al., 1996). The Stat4–/– mice were backcrossed eight generations to the C57BL/6 genetic background. The transgenic expression vector was generated by cloning human Stat4α or Stat4β cDNAs within the CD2 LCR (Zhumabekov et al., 1995). Stat4 transgenic mice (CD2:Stat4α and CD2:Stat4β) were generated by the Indiana University transgenic facility (on a C3H genetic background) and backcrossed two generations to C57BL/6 mice and 3–4 generations to Stat4–/– C57BL/6 mice. The controls were transgene-negative Stat4+/– mice or wild type C57BL/6 mice purchased from Harlan Bioproducts (Indianapolis, IN). Mice were genotyped for the presence of the transgene either by Southern blot using the Stat4 cDNA as a probe or by PCR (conditions available on request). The presence of wild-type and Stat4-targeted alleles was typed by PCR. Western analysis was performed using 100 µg of total cellular extract and anti-Stat4 monoclonal (BD Transduction Laboratories, San Diego CA).

T-cell differentiation, gene expression and proliferation analysis

Purified CD4+ cells of the indicated genotype were differentiated into Th1 and Th2 cells as described (Zhang et al., 2000b). Total RNA was isolated following treatment with the indicated stimuli for 24 h using Trizol (Life Technologies), run on a formaldehyde–agarose gel, transferred to a nylon membrane and hybridized to the indicated cDNAs. IFN-γ levels were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using specific monoclonal antibodies (BD Pharmingen). For analysis of proliferation, Th1 cells were incubated at 5 × 104/well in a round-bottom microtiter plate with the indicated concentration of IL-12. All cultures were incubated in the presence of anti-IL-2 (S4B6) at 5 µg/ml. Cultures were pulsed with 1 µCi of [3H]thymidine for the last 18 h of a 24, 48 or 72 h culture period. Cultures were harvested and samples counted by scintillation counter.

DNA binding assays

For DNA precipitation experiments, oligonucleotides corresponding to the IRF-1 STAT/CRE element (5′-AGCCTGATTTCCCCGAAATGACGGCACG-3′ and the complement) (Coccia et al., 1999; Galon et al., 1999) were biotinylated on one strand and coupled to streptavidin–agarose (Sigma, St Louis, MO) at a concentration of 1 µg/ml. The beads were equilibrated in 0.1 M KCl-HEMG (25 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol) plus 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), phosphatase inhibitors (1 mM NaVO4 and 5 mM NaF) and protease inhibitors. Activated T cells were stimulated with 2 ng/ml IL-12 for the indicated time points, and nuclear extracts were prepared using the Pierce Chemical Co. NE-PER reagents. Binding reactions were carried out in a volume of 1 ml of 0.1 M KCl-HEMG for 30 min at 4°C with 10 µg of poly(dIdC). The beads were washed three times with 0.5 ml of 0.1 M KCl-HEMG. Specifically bound proteins were eluted with SDS sample buffer and analyzed by western blot using a monoclonal anti-Stat4 (BD Transduction Labs).

Array analysis

Pooled Th1 cells from CD2:Stat4α and CD2:Stat4β cultures (two mice of each genotype) were stimulated with 2 ng/ml IL-12 for 6 or 18 h. Total RNA was isolated as described above and purified using the Qiagen Isolation Kit. Microarray analysis was carried out using arrays with ∼24 000 murine genes at Rosetta Inpharmatics fabricated using their ink-jet oligonucleotide synthesizer technology (Hughes et al., 2001). Data were analyzed with Tularik MicroArray eXplorer (TMAX) software, and an arbitrary level of 2-fold average induction was chosen for further analysis and presentation. The mean fold variation between duplicate runs of microarray analysis was 0.23.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank D.Bohmann for the HA-ubiquitin expression vector, J.Klein for the A139 cell line, C.Carter-Su for the SH2-B probe, Genetics Institute for murine IL-12, Sekar Venkataraman for critical comments on the manuscript, Victoria Lawless and India Oldham for technical assistance, and our colleagues in the lab for helpful discussions, particularly Todd Dubnicoff, Tom Mikita and Uli Schindler. This work was supported by NIH grant AI45515 to M.H.K.

References

- Afanasyeva M., Wang,Y., Kaya,Z., Stafford,E.A., Dohmen,K.M., Sadighi Akha,A.A. and Rose,N.R. (2001) Interleukin-12 receptor/STAT4 signaling is required for the development of autoimmune myocarditis in mice by an interferon-γ-independent pathway. Circulation, 104, 3145–3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon C.M., Petricoin,E.F.,III, Ortaldo,J.R., Rees,R.C., Larner,A.C., Johnston,J.A. and O’Shea,J.J. (1995) Interleukin 12 induces tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of Stat4 in human lymphocytes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 7307–7311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg J.F., Horvath,C.M., Wen,Z., Schreiber,R.D. and Darnell,J.E.J. (1996) Transcriptionally active Stat1 is required for the antiproliferative effects of both interferon α and γ. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 7673–7678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broxmeyer H.E. et al. (2002) Th1 cells regulate hematopoietic progenitor cell homeostasis by production of oncostatin M. Immunity, 16, 815–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai G., Radzanowski,T., Villegas,E.N., Kastelein,R. and Hunter,C.A. (2000) Identification of STAT4-dependent and independent mechanisms of resistance to Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol., 165, 2619–2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldenhoven E., van Dijk,T.B., Solari,R., Armstrong,J., Raaijmakers,J.A., Lammers,J.W., Koenderman,L. and de Groot,R.P. (1996) STAT3β, a splice variant of transcription factor STAT3, is a dominant negative regulator of transcription. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 13221–13227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitnis T., Najafian,N., Benou,C., Salama,A.D., Grusby,M.J., Sayegh,M.H. and Khoury,S.J. (2001) Effect of targeted disruption of STAT4 and STAT6 on the induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Clin. Invest., 108, 739–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S.S., Bacon,C.M., Sudarshan,C., Rees,R.C., Finbloom,D., Pine,R. and O’Shea,J.J. (1996) Activation of Stat4 by IL-12 and IFN-α: evidence for the involvement of ligand induced tyrosine and serine phosphorylation. J. Immunol., 157, 4781–4789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia E.M., Passini,N., Battistini,A., Pini,C., Sinigaglia,F. and Rogge,L. (1999) Interleukin-12 induces expression of interferon regulatory factor-1 via signal transducer and activator of transcription-4 in human T helper type 1 cells. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 6698–6703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell J.E.J. (1997) STATs and gene regulation. Science, 277, 1630–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galon J., Sudarshan,C., Ito,S., Finbloom,D. and O’Shea,J.J. (1999) IL-12 induces IFN regulating factor-1 (IRF-1) gene expression in human NK and T cells. J. Immunol., 162, 7256–7262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoey T., Sun,Y.L., Williamson,K. and Xu,X. (1995) Isolation of two new members of the NF-AT gene family and functional characterization of the NF-AT proteins. Immunity, 2, 461–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holz A., Bot,A., Coon,B., Wolfe,T., Grusby,M.J. and von Herrath,M.G. (1999) Disruption of the STAT4 signaling pathway protects from autoimmune diabetes while retaining antiviral immune competence. J. Immunol., 163, 5374–5382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T.R. et al. (2001) Expression profiling using microarrays fabricated by an ink-jet oligonucleotide synthesizer. Nat. Biotechnol., 19, 342–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki M., Mukai,T., Nakajima,C., Yang,Y.F., Gao,P., Yamaguchi,N., Tomura,M., Fujiwara,H. and Hamaoka,T. (2001) A mandatory role for STAT4 in IL-12 induction of mouse T cell CCR5. J. Immunol., 167, 6877–6883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N.G., Szabo,S.J., Weber-Nordt,R.M., Zhong,Z., Schreiber,R.D., Darnell,J.E.,Jr and Murphy,K.M. (1995) Interleukin 12 signaling in T helper type 1 (Th1) cells involves tyrosine phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcripton (Stat)3 and Stat4. J. Exp. Med., 181, 1755–1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan M.H., Sun,Y.-L., Hoey,T. and Grusby,M.J. (1996) Impaired IL-12 responses and enhanced development of Th2 cells in Stat4-deficient mice. Nature, 382, 174–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein J.L., Fickenscher,H., Holliday,J.E., Biesinger,B. and Fleckenstein,B. (1996) Herpesvirus saimiri immortalized γδ T cell line activated by IL-12. J. Immunol., 156, 2754–2760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawless V.A., Zhang,S., Ozes,O.N., Bruns,H.A., Oldham,I., Hoey,T., Grusby,M.J. and Kaplan,M.H. (2000) Stat4 regulates multiple components of IFN-γ-inducing signaling pathways. J. Immunol., 165, 6803–6808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard W.J. and O’Shea,J.J. (1998) Jaks and STATs: biological implications. Annu. Rev. Immunol., 16, 293–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsukawa A., Kaplan,M.H., Hogaboam,C.M., Lukacs,N.W. and Kunkel,S.L. (2001) Pivotal role of signal transducer and activator of transcription (Stat)4 and Stat6 in the innate immune response during sepsis. J. Exp. Med., 193, 679–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikita T., Campbell,D., Wu,P., Williamson,K. and Schindler,U. (1996) Requirements for interleukin-4-induced gene expression and functional characterization of Stat6. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 5811–5820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morinobu A., Gadina,M., Strober,W., Visconti,R., Fornace,A., Montagna,C., Feldman,G.M., Nishikomori,R. and O’Shea,J.J. (2002) STAT4 serine phosphorylation is critical for IL-12-induced IFN-γ production but not for cell proliferation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 12281–12286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mount S.M. (1982) A catalogue of splice junction sequences. Nucleic Acids Res., 10, 459–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy T.L., Geissal,E.D., Farrar,J.D. and Murphy,K.M. (2000) Role of the Stat4 N domain in receptor proximal tyrosine phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 7121–7131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musti A.M., Treier,M. and Bohmann,D. (1997) Reduced ubiquitin-dependent degradation of c-Jun after phosphorylation by MAP kinases. Science, 275, 400–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen K.B., Watford,W.T., Salomon,R., Hofmann,S.R., Pien,G.C., Morinobu,A., Gadina,M., O’Shea,J.J. and Biron,C.A. (2002) Critical role for STAT4 activation by type 1 interferons in the interferon-γ response to viral infection. Science, 297, 2063–2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien K.B., O’Shea,J.J. and Carter-Su,C. (2002) SH2-B family members differentially regulate JAK family tyrosine kinases. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 8673–8681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea J.J. (1997) Jaks, STATs, cytokine signal transduction and immunoregulation: are we there yet? Immunity, 7, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppmann B. et al. (2000) Novel p19 protein engages IL-12p40 to form a cytokine, IL-23, with biological activities similar as well as distinct from IL-12. Immunity, 13, 715–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang W., Jacobson,N.G., Bhattacharya,D., Gorham,J.D., Fenoglio,D., Sha,W.C., Murphy,T.L. and Murphy,K.M. (1999) The Ets transcription factor ERM is Th1-specific and induced by IL-12 through a Stat4-dependent pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 3888–3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park O.K., Schaefer,L.K., Wang,W. and Schaefer,T.S. (2000) Dimer stability as a determinant of differential DNA binding activity of Stat3 isoforms. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 32244–32249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi S.A., Leung,S., Kerr,I.M., Stark,G.R. and Darnell,J.E.,Jr (1996) Function of Stat2 protein in transcriptional activation by α interferon. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 288–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui L. and Carter-Su,C. (1999) Identification of SH2-bβ as a potent cytoplasmic activator of the tyrosine kinase Janus kinase 2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 7172–7177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer T.S., Sanders,L.K. and Nathans,D. (1995) Cooperative transcriptional activity of Jun and Stat3β, a short form of Stat3. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 9097–9101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer T.S., Sanders,L.K., Park,O.K. and Nathans,D. (1997) Functional differences between Stat3α and Stat3β. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 5307–5316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler C., Fu,X.Y., Improta,T., Aebersold,R. and Darnell,J.E.,Jr (1992) Proteins of transcription factor ISGF-3: one gene encodes the 91- and 84-kDa ISGF-3 proteins that are activated by interferon α. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 7836–7839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen R. and Kaplan,M.H. (2002) The homeostasis but not the differentiation of T cells is regulated by p27Kip1. J. Immunol., 169, 714–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuai K., Stark,G.R., Kerr,I.M. and Darnell,J.E.,Jr (1993) A single phosphotyrosine residue of Stat91 required for gene activation by interferon-γ. Science, 261, 1744–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuai K., Liao,J. and Song,M.M. (1996) Enhancement of antipro liferative activity of γ interferon by the specific inhibition of tyrosine dephosphorylation of Stat1. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 4932–4941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson S.J., Shah,S., Comiskey,M., de Jong,Y.P., Wang,B., Mizoguchi,E., Bhan,A.K. and Terhorst,C. (1998) T cell-mediated pathology in two models of experimental colitis depends predominantly on the interleukin 12/signal transducer and activator of transcription (Stat)-4 pathway, but is not conditional on interferon γ expression by T cells. J. Exp. Med., 187, 1225–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamm L.M., Satoskar,A.A., Ghosh,S.K., David,J.R. and Satoskar,A.R. (1999) STAT-4 mediated IL-12 signaling pathway is critical for the development of protective immunity in cutaneous leishmaniasis. Eur. J. Immunol., 29, 2524–2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarleton R.L., Grusby,M.J. and Zhang,L. (2000) Increased susceptibility of Stat4-deficient and enhanced resistance in Stat6-deficient mice to infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Immunol., 165, 1520–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekkanat K.K., Maassab,H., Berlin,A.A., Lincoln,P.M., Evanoff,H.L., Kaplan,M.H. and Lukacs,N.W. (2001) Role of interleukin-12 and stat-4 in the regulation of airway inflammation and hyperreactivity in respiratory syncytial virus infection. Am. J. Pathol., 159, 631–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thierfelder W.E. et al. (1996) Requirement for Stat4 in interleukin-12 mediated responses of natural killer and T cells. Nature, 382, 171–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinchieri G. (1995) Interleukin-12: a proinflammatory cytokine with immunoregulatory functions that bridge innate resistance and antigen-specific adaptive immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol., 13, 251–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataraman C., Schaefer,G. and Schindler,U. (2000) Cutting edge: Chandra, a novel four-transmembrane domain protein differentially expressed in helper type 1 lymphocytes. J. Immunol., 165, 632–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinkemeier U., Cohen,S.L., Moarefi,I., Chait,B.T., Kuriyan,J. and Darnell,J.E.,Jr (1996) DNA binding of in vitro activated Stat1α, Stat1β and truncated Stat1: interaction between NH2-terminal domains stabilizes binding of two dimers to tandem DNA sites. EMBO J., 15, 5616–5626. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinkemeier U., Moarefi,I., Darnell,J.E.,Jr. and Kuriyan,J. (1998) Structure of the amino-terminal protein interaction domain of STAT-4. Science, 279, 1048–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visconti R., Gadina,M., Chiariello,M., Chen,E.H., Stancato,L.F., Gutkind,J.S. and O’Shea,J.J. (2000) Importance of the MKK6/p38 pathway for interleukin-12-induced STAT4 serine phosphorylation and transcriptional activity. Blood, 96, 1844–1852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Stravopodis,D., Teglund,S., Kitazawa,J. and Ihle,J.N. (1996) Naturally occurring dominant negative variants of Stat5. Mol. Cell. Biol., 16, 6141–6148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Moriggl,R., Stravopodis,D., Carpino,N., Marine,J.C., Teglund,S., Feng,J. and Ihle,J.N. (2000) A small amphipathic α-helical region is required for transcriptional activities and proteasome-dependent turnover of the tyrosine-phosphorylated Stat5. EMBO J., 19, 392–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z., Zhong,Z. and Darnell,J.E.,Jr (1995) Maximal activation of transcription by Stat1 and Stat3 requires both tyrosine and serine phosphorylation. Cell, 82, 241–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White S.J., Underhill,G.H., Kaplan,M.H. and Kansas,G.S. (2001) Cutting edge: differential requirements for Stat4 in expression of glycosyltransferases responsible for selectin ligand formation in Th1 cells. J. Immunol., 167, 628–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams T., Admon,A., Luscher,B. and Tjian,R. (1988) Cloning and expression of AP-2, a cell-type-specific transcription factor that activates inducible enhancer elements. Genes Dev., 2, 1557–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Sun,Y.-L. and Hoey,T. (1996) Cooperative DNA binding and sequence-selective recognition conferred by the STAT amino-terminal domain. Science, 273, 794–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan R., Qureshi,S., Zhong,Z., Wen,Z. and Darnell,J.E.,Jr (1995) The genomic structure of the STAT genes: multiple exons in coincident sites in Stat1 and Stat2. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 459–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo J.Y., Huso,D.L., Nathans,D. and Desiderio,S. (2002) Specific ablation of Stat3β distorts the pattern of Stat3-responsive gene expression and impairs recovery from endotoxic shock. Cell, 108, 331–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. and Kaplan,M.H. (2000) The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for IL-12-induced IFN-γ expression. J. Immunol., 165, 1374–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Lawless,V.A. and Kaplan,M.H. (2000a) Cytokine-stimulated T lymphocyte proliferation is regulated by p27Kip1. J. Immunol., 165, 6270–6277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Lukacs,N.W., Lawless,V.A., Kunkel,S.L. and Kaplan,M.H. (2000b) Differential expression of chemokines in Th1 and Th2 cells is dependent on Stat6 but not Stat4. J. Immunol., 165, 10–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Wrzeszczynska,M.H., Horvath,C.M. and Darnell,J.E.,Jr (1999) Interacting regions in Stat3 and c-Jun that participate in cooperative transcriptional activation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 7138–7146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhumabekov T., Corbella,P., Tolaini,M. and Kioussis,D. (1995) Improved version of a human CD2 minigene based vector for T cell-specific expression in transgenic mice. J. Immunol. Methods, 185, 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]