Abstract

The execution of apoptosis depends on the hierarchical activation of caspases. The initiator procaspases become autoproteolytically activated through a less understood process that is triggered by oligomerization. Procaspase-8, an initiator caspase recruited to death receptors, is activated through two cleavage events that proceed in a defined order to generate the large and small subunits of the mature protease. Here we show that dimerization of procaspase-8 produces enzymatically competent precursors through the stable homophilic interaction of the procaspase-8 protease domain. These dimers are also more susceptible to processing than individual procaspase-8 molecules, which leads to their cross-cleavage. The order of the two interdimer cleavage events is maintained by a sequential accessibility mechanism: the separation of the large and small subunits renders the region between the large subunit and prodomain susceptible to further cleavage. In addition, the activation process involves an alteration in the enzymatic properties of caspase-8; while procaspase-8 molecules specifically process one another, mature caspases only cleave effector caspases. These results reveal the key steps leading to the activation of procaspase-8 by oligomerization.

Keywords: apoptosis/caspase-8/CD95(Fas/APO-1)/interdimer cleavage/oligomerization

Introduction

Apoptosis is executed by caspases, a family of cysteine proteases that cleave proteins after aspartic acid residues (Thornberry and Lazebnik, 1998; Earnshaw et al., 1999; Nicholson, 1999; Chang and Yang, 2000; Hengartner, 2000). These proteases are synthesized as latent precursors consisting of an N-terminal prodomain of varying length and a signature C-terminal protease domain that can be further divided into the large and small subunits, which are found in mature caspases. During apoptosis, procaspases are sequentially activated through proteolytic processing at aspartic acid residues. Long prodomain-containing initiator caspases are autoproteolytically activated via a mechanism involving oligomerization. Active initiator caspases then process short prodomain-containing effector caspases, which in turn cleave a wide range of cellular proteins to dismantle cells. Such a caspase cascade ensures the quick generation of a massive amount of active caspases during apoptosis. However, caspase activation, particularly that of initiator caspases, needs to be tightly regulated in healthy cells to prevent accidental cell death. How this is achieved through oligomerization-induced activation of initiator caspases is not well understood.

A major mammalian apoptotic pathway is that mediated by a group of death receptors in the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily, which includes TNFR1, CD95 (Fas/APO-1) and death receptors (DR) 3–6. These receptors play crucial roles in the regulation of immune responses. CD95-mediated apoptosis, for example, is critical for the maintenance of peripheral immune tolerance and the elimination of cells infected by viruses (Ashkenazi and Dixit, 1998; Peter et al., 1998; Krammer, 2000; Siegel et al., 2000; Wajant, 2002). Upon binding to their corresponding trimeric ligands or agonistic antibodies, these receptors recruit an initiator procaspase, procaspase-8, to the membrane-associated death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) (Medema et al., 1997). The critical role of caspase-8 in death receptor-mediated apoptosis is underscored by the observation that cells deficient in caspase-8 are resistant to apoptosis mediated by these receptors (Juo et al., 1998; Varfolomeev et al., 1998). In addition, caspase-8 participates in apoptosis induced by expanded polyglutamine repeats, which are associated with various neurodegenerative diseases (Sanchez et al., 1999; Gervais et al., 2002).

The activation of procaspase-8 in the DISC is triggered by either its homo-oligomerization (Martin et al., 1998; Muzio et al., 1998; Yang et al., 1998a) or its hetero-oligomerization with a caspase-8-like proteolytically inactive molecule, c-FLIPL (Chang et al., 2002; Micheau et al., 2002). Active caspase-8 is then released into the cytosol, where it cleaves effector caspases such as caspase-3. The release of mature caspase-8 to the cytosol is critical for apoptosis indication (Martin et al., 1998). Full activation of procaspase-8 requires two cleavage events: one that separates the large and small subunits, and another that separates the large subunit and the prodomain. Because procaspase-8 binds to the DISC through its N-terminal prodomain, processing needs to proceed in a defined order, with the first cleavage occurring within the protease domain to separate the large and small subunits (Medema et al., 1997), to ensure that the processed and not the unprocessed protease domain is released into the cytosol. However, little is known about the mechanism by which this order of cleavage events is maintained.

Paradoxically, in addition to being an integral component of apoptotic cell death, caspase-8 is also required for the proliferation of lymphocytes. T cells lacking caspase-8 activity are not only resistant to apoptosis, but also fail to generate interleukin 2 and to proliferate (Chun et al., 2002; Salmena et al., 2003). The dual role of caspase-8 in cell proliferation and death may help to ensure that activated lymphocytes can be deleted after activation, a critical property of immune cells. The mechanism underlying this dual role of caspase-8 remains unknown.

In the present study, we address the mechanism of oligomerization-induced activation of procaspase-8 by using an inducible biochemical system for caspase-8 activation in combination with analyses of the DISC complex. We propose an ‘interdimer processing’ mechanism for caspase-8 activation, and discuss how this mechanism may be suited for the control of the caspase cascade as well as how it may explain the dual role of caspase-8 in proliferation and apoptosis.

Results

Inducible caspase-8 activation in vitro

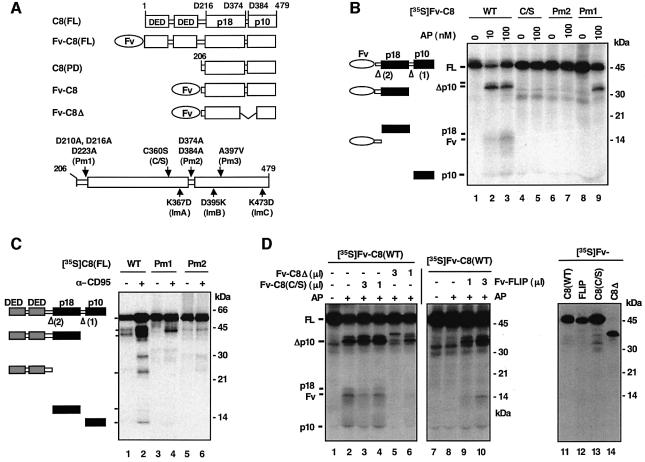

We have previously studied procaspase activation in a cell-free system based on FK506 binding protein (FKBP) mediated clustering of the zymogen molecules (Yang et al., 1998a,b). To establish the mechanism of oligomerization-induced caspase-8 activation, we first improved this system by using Fv, a derivative of FKBP. A divalent compound AP1903 and its close relative AP20187 bind with high affinity to Fv but not to FKBP, thereby minimizing the interference of endogenous FKBP and allowing for effective oligomerization (Clackson et al., 1998). As shown in Figure 1B, the addition of AP20187 to in vitro translated [35S]methionine-labeled Fv fusion of the caspase-8 protease domain, Fv-C8(WT), led to the self-processing of the zymogen and generation of mature caspase-8 subunits (lanes 2 and 3). Gel filtration analyses confirmed AP20187-induced formation of dimeric Fv-C8 proteins (data not shown). Activation of caspase-8 in this system faithfully mimics that which occurs in the DISC (Medema et al., 1997). The activation proceeds with the same order of cleavage events, with the first separating the large and small subunits, and the second separating the large subunit and prodomain. This was shown both by the effects of processing mutations that abolished each of these cleavage events and by the order of appearance of the processing intermediates (Figure 1B, lanes 7 and 9, and C, lanes 4 and 6).

Fig. 1. Oligomerization-induced caspase-8 activation in vitro. (A) Schematic representation of procaspase-8 and its fusions/mutations: C8(FL), full-length caspase-8; DED, death effector domain; p18 and p10, the large and small subunits that form mature caspase-8; D, cleave site aspartic acid residue; Fv-C8(FL), Fv fusion of full-length caspase-8; Fv, an FK506 binding protein 12 (FKBP12) derivative with the Phe36 to Val mutation; C8(PD), caspase-8 protease domain (amino acids 206–479); Fv-C8, Fv fusion of caspase-8 protein domain; Fv-C8Δ, Fv-C8 lacking amino acids 370–434. Shown on the bottom are various point mutations used in this work: Pm, processing mutant; Im, interface mutant. (B) Inducible activation of caspase-8 in vitro. In vitro translated 35S-labeled Fv-C8 proteins were treated with the indicated concentration of AP20187 (AP). WT, wild type. Reaction mixes were resolved by SDS–PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography. The deduced domain structures of the indicated bands are shown on the left. Arrowheads indicate cleavage sites and the numbers in parentheses mark the order of cleavage. Molecular weight standards are shown on the right. (C) Processing of caspase-8 in the CD95 death-inducing signaling complex (DISC). 35S-labeled full-length wild-type or mutant caspase-8 proteins were treated with CD95 complex isolated from SKW6.4 cells that were either unstimulated (–) or stimulated with an agnostic antibody anti-CD95 (+). Deduced domain structures and molecular weight standards are shown. (D) Effects of catalytic mutants on the processing of wild-type caspase-8. Left and middle panels: 1 µl of in vitro translated [35S]Fv-C8(WT) was treated with AP20187 for 4 h (lanes 1–6) or 2 h (lanes 7–10). In vitro translated non-radiolabeled Fv fusion proteins were added as indicated. Right panel, 1 µl of in vitro translated 35S-labeled proteins was analyzed by autoradiography to show the relative levels of protein expression (lanes 11–14).

The observation that oligomerization induces initiator caspase activation has led to the hypothesis that individual procaspase-8 molecules cleave one another upon oligomerization (Salvesen and Dixit, 1999), reminiscent of the cross-phosphorylation of individual receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) (Schlessinger, 2000). This model predicts that a protease-defective caspase-8 mutant should have a dominant-negative effect on the activation of wild-type caspase-8. To test this model, we examined two such mutants: one that contained the active site Cys360 to Ser mutation, but otherwise had an intact protease domain, and the other that lacked 65 amino acids of the protease domain (Fv-C8Δ; Figure 1A). While the deletion mutant robustly inhibited the processing of wild-type caspase-8 (Figure 1D, lanes 5 and 6), the point mutant only showed a minimal inhibitory effect (lanes 3 and 4). The latter result was consistent with a recent study (Chen et al., 2002). In addition, c-FLIPL, a caspase-8-like DISC component with no detectable caspase activity, was found to enhance rather than inhibit caspase-8 activation (Chang et al., 2002; Micheau et al., 2002) (Figure 1D, lanes 9 and 10). These results indicate that individual procaspase-8 molecules in close proximity are unlikely to cleave one another. Because both Fv-C8(C/S) and Fv-FLIPL maintain an intact protease/protease-like domain while Fv-C8Δ does not, it is possible that caspase-8 molecules become activated via association with each other through their protease domains.

Caspase-8 zymogen acquires proteolytic activity upon dimerization

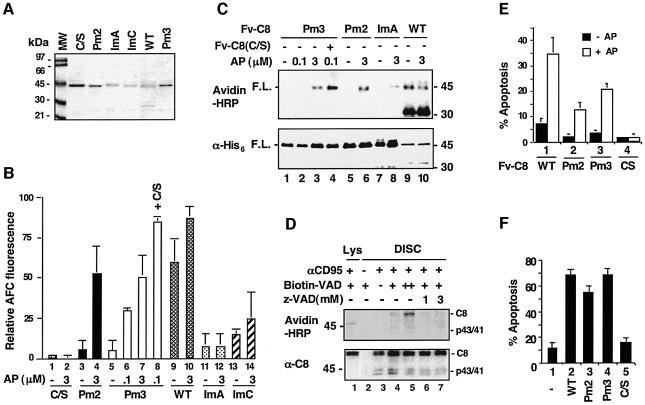

A mature caspase-8 molecule, like other active caspases, is a tetramer consisting of two large and two small subunits generated from two separate procaspase-8 molecules (Watt et al., 1999; Blanchard et al., 2000). Formation of a mature caspase-like structure by two unprocessed procaspases seems difficult due to structural constraints, but could become feasible upon forced dimerization like that occurring during apoptosis. To examine this possibility, we first determined whether dimerization enables procaspase-8 molecules to become enzymatically active without self-processing. Two non-processible caspase-8 mutations were used. The first mutation changed the processing site aspartic acids between the large and small subunits (Asp374 and Asp384) to alanines (processing mutation 2 or Pm2, Figure 1A–C). The second one harbored an Ala397 to Val (Pm3) mutation, which was identified through random PCR mutagenesis (see Materials and methods). Fv-C8(Pm2) and Fv-C8(Pm3) were expressed in bacteria and purified to homogeneity. When the recombinant proteins were treated with AP20187, they showed significant caspase activity, as assayed both by a fluorogenic caspase substrate (IETD-AFC) (Figure 2B, lane 4 versus 3 and lanes 6–8 versus 5) as well as by labeling proteins with a biotinylated active site-directed pan-caspase inhibitor (biotin-z-VAD) (Figure 2C, lanes 3 and 4 versus lane 1, and lane 6 versus lane 5). The latter assay confirmed that the caspase activity originated from full-length Fv fusion proteins instead of an aberrant processing product(s). To confirm that the full-length procaspase-8 molecules in the DISC are enzymatically active, we isolated the DISC complex from the CD95-sensitive SKW6.4 cells and treated it with biotin-VAD. The full-length procaspase-8 molecules as well as the processing intermediates in the DISC were labeled with the inhibitor, but the procaspase-8 molecules in the cytosol were not (Figure 2D). Together, these data show that dimerization induces significant enzymatic activity in the caspase-8 zymogen prior to processing.

Fig. 2. Dimerization-induced caspase activity in caspase-8 zymogen. (A) Recombinant Fv-C8 fusions. Purified Fv-C8 proteins (10 µl each) were resolved by SDS–PAGE and visualized by Coomassie staining. Fv-C8(WT) was partially processed during bacterial expression. The effects of dimerization on the protease activity of non-processible and interface caspase-8 mutants are shown in (B) and (C). (B) Fv-C8 proteins (50 ng each) were treated with AP20187 for 4 h and then tested for proteolysis of the fluorogenic substrate IETD-AFC. Lane 14 also contained 10 ng of Fv-C8(C/S). (C) Fv-C8 proteins (50 ng) were incubated with AP20187 (+) or vehicle (–) before being labeled with biotinylated VAD-fmk. Lane 4 contained 10 ng of Fv-C8(C/S). Reaction mixes were separated by SDS–PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with either avidin–HRP to detect the labeled species (top) or anti-His6 to detect proteins (bottom). (D) Procaspase-8 in the DISC complex is enzymatically active. CD95 complex from BJAB cells that were either stimulated (+) with anti-CD95 or unstimulated (–). Cell lysates (lys) and the DISC complex were treated with vehicle (–) or with 30 µM (+) or 100 µM (++) biotinylated VAD-fmk. Non-biotinylated z-VAD-fmk was included in the reaction as indicated. The reaction mixes were analyzed by immunoblotting with either avidin–HRP (top) or anti-caspase-8 C15 (bottom). The cell death activity of the caspase-8 precursor is shown in (E) and (F). HeLa cells were transfected with (E) 100 ng of plasmids expressing the indicated Fv-C8 proteins plus an EGFP expressing plasmid and treated with AP20187 (+) or vehicle (–), or (F) 1 µg of plasmids expressing the full-length caspase-8 proteins plus the EGFP plasmid. Apoptosis was scored among GFP-positive cells 18–24 h later.

To determine whether the activity of the caspase-8 zymogen was sufficient to induce cell death, Fv-C8(Pm2) and Fv-C8(Pm3) were transiently expressed in HeLa cells. In the presence, but not in the absence, of AP20187, Fv-C8(Pm2) and Fv-C8(Pm3) stimulated cell death to levels of ∼40 and 60%, respectively, of that caused by Fv-C8(WT) (Figure 2E, columns 2 and 3 versus column 1). In addition, when full-length caspase-8 proteins carrying the Pm2 and Pm3 mutations were introduced into HeLa cells, they caused significant cell death comparable to that induced by wild-type caspase-8 (Figure 2F). Upon overexpression in mammalian cells, procaspase-8 can self-associate through the prodomain. Thus, the dimerization-induced activity of procaspase-8 is sufficient for apoptosis induction upon overexpression.

Procaspase-8 activation requires stable association of the protease domain

We next assessed whether the stable association of the protease domains is required for caspase-8 activation. Analysis of the crystal structure of mature caspase-8 revealed amino acid residues at the interface of two p20:p10 heterodimers that contribute to the association of these dimers (Watt et al., 1999; Blanchard et al., 2000). We mutated three residues (Lys367, Asp395 and Lys473) to those of opposite charges, yielding interface mutation (Im) A to C (Figures 1A and 3A). The Im mutations were found to severely decrease the homophilic association of the procaspase-8 protease domain (Figure 3B, lanes 3–5). When the Fv-C8 fusions carrying these mutations were treated with AP20187, none of them underwent processing (Figure 3C, lanes 4, 6 and 8). Furthermore, recombinant Fv-C8 fusions harboring these mutations exhibited little activity even after AP20187 treatment (Figure 2B, lanes 12 and 14, Figure 2C, lane 8; data not shown). In addition, homodimers of these mutants were not able to process other procaspase-8 molecules (data not shown). To assess the effect of these interface mutations on the function of full-length caspase-8, we introduced the corresponding full-length mutants into caspase-8-deficient Jurkat cells. CD95-induced apoptosis in these cells was restored by wild-type caspase-8, but the interface mutants showed significantly reduced apoptosis (Figure 3D).

Fig. 3. Procaspase-8 activation requires stable association of the protease domain. (A) Crystal structure of the mature caspase-8 heterotetramer bound to the DEVD-CHO inhibitor (Blanchard et al., 2000) (courtesy of H.Blanchard et al.). Positions of Lys367, Asp395, Ala397 and Lys473, the N-terminus of p10 (Np10) and the C-terminus of p20 (Cp20) are indicated on one half of the tetrameric molecule. (B) Interface mutations that impair the homophilic interaction of the caspase-8 protease domain. Top and middle panels: 35S-labeled caspase-8 protease domains (each contains an HA tag) were mixed with non-radiolabeled protease domains (each contains a FLAG tag), as indicated. The mixes were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody M2 conjugated on agarose beads, and the bound proteins (top) and input proteins (middle) were analyzed by autoradiography. Bottom panel: in a parallel experiment, the immunoprecipitation was performed with non-radiolabeled HA-tagged proteins and 35S-labeled FLAG-tagged proteins. The bound FLAG tagged proteins were analyzed by autoradiography. The ImB mutant migrated faster than the other proteins on SDS–PAGE, probably caused by the change of a negatively charged residue to a positive one. (C) Defective processing of the caspase-8 interface mutants. the experiment was performed as in Figure 1B. (D) Full-length interface mutants failed to restore apoptosis in caspase-8-deficient cells. Caspase-8-deficient Jurkat cells were transfected with vector (–) or with constructs expressing either wild-type or mutant full-length caspase-8 proteins, plus pEGFP. Cells were treated with anti-CD95 and the percentage of apoptosis among GFP-positive cells was determined by annexin V staining. None of the interface mutations affected protein stability (data not shown). (E) Restoration of protease activity of interface mutants by c-FLIPL. [35S]Fv-C8(ImA) (lanes 1–3) or [35S]Fv-FLIP (lanes 4–6) was treated with AP20187 (+) or vehicle (–). An equal amount of non-radiolabeled proteins was included as indicated. Similar results were obtained for Fv-C8(ImB) and Fv-C8(ImC) (data not shown).

To rule out the possibility that these mutants were incapable of forming an active site, we heterodimerized each of them with the caspase-8 activator c-FLIPL. Owing to the 2-fold symmetry of a mature caspase complex, an interface mutation impairs two bonds while their heterodimerization with c-FLIPL restores one of them. When Fv-C8 containing the interface mutants were heterodimerized with Fv-FLIP, each of the mutants was able to process itself as well as c-FLIPL (Figure 3E; data not shown). Therefore, the interface mutant retained the ability to form an active site and specifically affected homophilic interaction of procaspase-8 protease domains. Together, these results show that the formation of an active intermediate structurally similar to that of the mature caspase is a requisite step in procaspase-8 activation.

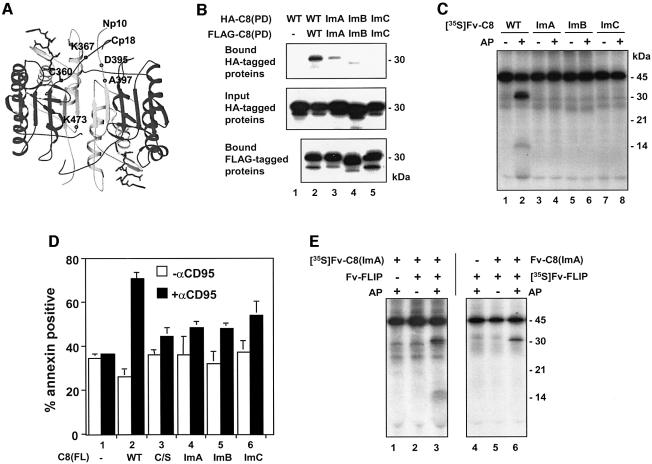

Dimerized procaspase-8 molecules serve as substrates for one another

We then wondered whether the next step in caspase-8 activation involves cleavage of individual or dimeric procaspase-8 molecules by the dimeric intermediate. Given that the CD95 ligand is a trimeric molecule and hence each DISC complex should in theory recruit three procaspase-8 molecules, it seems likely that the dimeric procaspase-8 intermediate would cleave the unpaired procaspase-8 molecule within the same DISC. However, favoring the interdimer cleavage mechanism is the observation that a higher order of oligomerization of receptors is often needed for effective apoptosis induction (Kischkel et al., 1995). To distinguish these two possibilities, we compared the processing of monomeric and dimeric Fv-C8(C/S) proteins by active procaspase-8 molecules. In an effort to generate sufficient amounts of active procaspase-8 independent of AP20187-induced dimerization, we found that fusion of full-length procaspase-8 to FKBP or Fv leads to spontaneous activation of the zymogen (Figure 4A). Activation of caspase-8 in this way, like AP20187-induced activation of Fv-C8, closely resembles that which occurs in the DISC in that it is autocatalytic in nature and proceeds in the same order of cleavage events (data not shown). The fusion proteins showed a significantly enhanced ability to self-associate through the prodomain (Figure 4B, lane 4 versus lane 2; data not shown), likely due to a conformational change caused by the FKBP/Fv moiety.

Fig. 4. Dimerization renders procaspase-8 molecules susceptible to cleavage. (A) Spontaneous activation of the FKBP and Fv fusion of full-length caspase-8. In vitro translated Fv-C8(FL) or Fv-C8(FL, C/S) was incubated at 30°C for the indicated duration before being analyzed by SDS–PAGE and autoradiography. Domain structures are shown on the left. Similar results were obtained for the FKBP fusion of caspase-8. (B) Stronger homophilic interaction of Fv-C8(FL). Left panel: mixes of [35S]Fv-C8 (FL) (lane 1 and 2) or [35S]C8(FL) (lanes 3 and 4) (containing an HA tag) with the corresponding non-radiolabeled proteins (+) (containing a FLAG tag) or control in vitro translation mix (–) were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG conjugated on agarose beads, and the bound (top) and input (bottom) proteins were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and autoradiography. Right panel: in a parallel experiment, the immunoprecipitation was carried out with non-radiolabeled HA-tagged proteins and 35S-labeled FLAG tagged proteins. (C) Dimerization enhances processing of Fv-C8(C/S) by FKBP-C8(FL). [35S]Fv-C8(C/S) was treated with the indicated non-radiolabeled FKBP fusion proteins in the presence (+) or absence (–) of AP20187. (D) Caspase-8 interface mutations abolished processing of Fv-C8 by FKBP-C8(FL). [35S]Fv-C8(C/S) or Fv-C8(ImA) was treated with FKBP-C8(FL). Similar results were obtained for Fv-C8(ImB) and Fv-C8(ImC) (data not shown). (E) Defective processing of the full-length caspase-8 interface mutants by the DISC. 35S-labeled full-length caspase-8 proteins were treated with the DISC complex as in Figure 1C.

When [35S]Fv-C8(C/S) was treated with FKBP-C8(FL), the processing of [35S]Fv-C8(C/S) was markedly enhanced upon addition of AP20187 (Figure 4C, lane 2 versus lane 1). Because AP20187 has nearly 1000-fold higher affinity to Fv than to FKBP (Clackson et al., 1998), it should induce the homodimerization of [35S]Fv-C8(C/S) but not of FKBP-C8(FL). Nor should it generate heterodimers of the two fusions. To ascertain this selectivity, we used FKBP-C8(PD), which contains only the procaspase-8 protease domain and does not undergo spontaneous self-processing, as a negative control. FKBP-C8(PD) did not cleave [35S]Fv-C8(C/S) in the presence of AP20187 (Figure 4C). However, when AP1510, a divalent ligand with similar affinity to Fv and FKBP (Clackson et al., 1998), was used, FKBP-C8(PD) strongly processed [35S]Fv-C8(C/S) (data not shown). The cleavage of Fv-C8(C/S) by FKBP-C8(FL) was due to the activity of the caspase-8 precursor because (i) as the self-processing of FKBP-C8(FL) proceeded, its ability to cleave Fv-C8(C/S) decreased (data not shown), and (ii) the mature caspase-8 protein could not process its own precursors (see below). Therefore oligomerization promotes cleavage among dimerized procaspase-8 intermediates.

To confirm that the homophilic association of the caspase-8 protease domain is required for its ability to be processed, we examined the processing of the interface mutants by the active caspase-8 precursor. When the Fv fusions of these mutants were treated with FKBP-C8(FL) in the presence of AP20187, none was processed (Figure 4D, lane 4; data not shown). Furthermore, when the full-length caspase-8 proteins harboring these mutations were treated with the DISC complex, the processing of the mutants was reduced compared with that of the wild-type protein (Figure 4E, lanes 4, 6 and 8). The residual processing was likely due to the heterodimerization of the mutants with the endogenous caspase-8 in the DISC. Thus, the interface mutants were defective not only as enzymes but also as substrates. Therefore, we conclude that procaspase-8 is activated by the cross-cleavage of dimerized zymogens.

Maintenance of the order of the two cleavage events that generate mature caspase-8

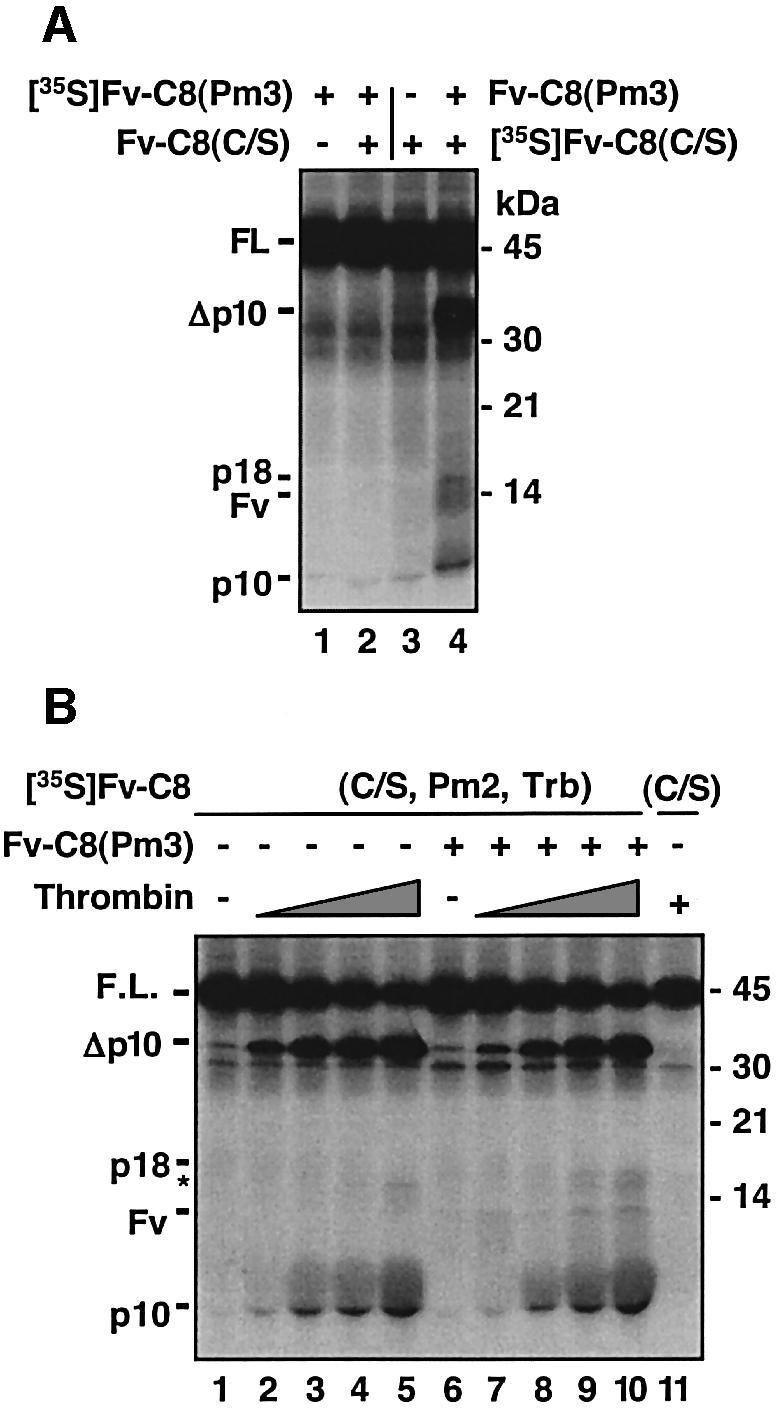

The two cleavage events that generate mature caspase-8 need to proceed in a defined order so that the processed rather than the unprocessed protease domain is released into the cytosol to activate effector caspases such as caspase-3. Two alternative models can explain how this order of events is achieved. First, the cleavage site between the large subunit and the prodomain might not be accessible to the active procaspase until the large and small subunits are separated (the sequential accessibility model). Secondly, the first cleavage might generate an intermediate product that specifically recognizes the second cleavage site (the sequential activity model). To distinguish between these possibilities, we first examined whether a non-processible mutant of caspase-8 could cleave Fv-C8(C/S). We found that Fv-C8(Pm2) was not suitable for this experiment because its activity was not high enough. The homophilic interaction of the protease domains of this non-processible mutant was weak compared with that of the wild-type protease domain (data not shown), likely due to the fact that one of the aspartic acids changed in this mutant, Asp374, also participates in the interaction between the two p18/p10 heterodimers (Watt et al., 1999; Blanchard et al., 2000). In comparison, the other non-processible mutant, Pm3, showed higher caspase activity, especially in the presence of Fv-C8(C/S) (Figure 2B and C), and also increased cyotoxicity (Figure 2E and F). When Fv-C8(C/S) was treated with Fv-C8(Pm3), it was processed to generate the signature mature caspase-8 subunits (Figure 5A, lane 4). This result indicates that the active procaspase-8 is able to process other precursors at both the region linking the large and small subunits and the region linking the prodomain and the large subunit.

Fig. 5. Sequential accessibility mechanism for maintaining the order of cleavage events. (A) A non-processible caspase-8 can process caspase-8(C/S) at both cleavage sites. The indicated combinations of 35S-labeled and non-radiolabeled proteins were treated with AP20187 or vehicle. (B) Severance of the large and small subunits allows for cleavage between the prodomain and the large subunit. [35S]Fv-C8(C/S, Pm2, Trb), which contains the indicated mutations and a thrombin cleavage site inserted between the large and small subunits, or Fv-C8(C/S) was treated with non-radiolabeled Fv-C8(Pm3) in the presence of AP20187. The mixes were incubated for 4 h at 30°C with increasing amounts of thrombin (0.36 × 10–4, 1.2 × 10–4, 3.6 × 10–4 and 12 × 10–4 U/µl), with 12 × 10–4 I/µl thrombin (+) or untreated (–) and analyzed by SDS–PAGE and autoradiography. The size of p18 was slightly larger than the wild-type p18 due to the cleavage at the thrombin site. The asterisk indicates a non-specific cleavage product.

To confirm that the separation of the large and small units renders the region between the large subunit and the prodomain accessible for cleavage, we introduced a thrombin cleavage site between the large and small subunits of Fv-C8(C/S, Pm2), which contained the indicated catalytic and processing mutations. When the resulting mutant, Fv-C8(C/S, Pm2, Trb), was treated with Fv-C8(A/V) in the presence of AP20187, the second cleavage that separates the prodomain and the large subunit occurred only after thrombin digestion that severed the large and small subunits (Figure 5B, lanes 7–10 versus lanes 2–5). Together, these results suggest that the site for the second cleavage is not accessible until the link between the large and small subunits is severed.

Change of substrate specificity during caspase-8 activation process

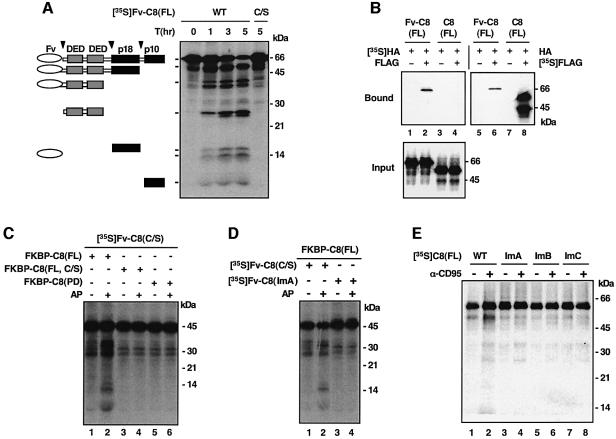

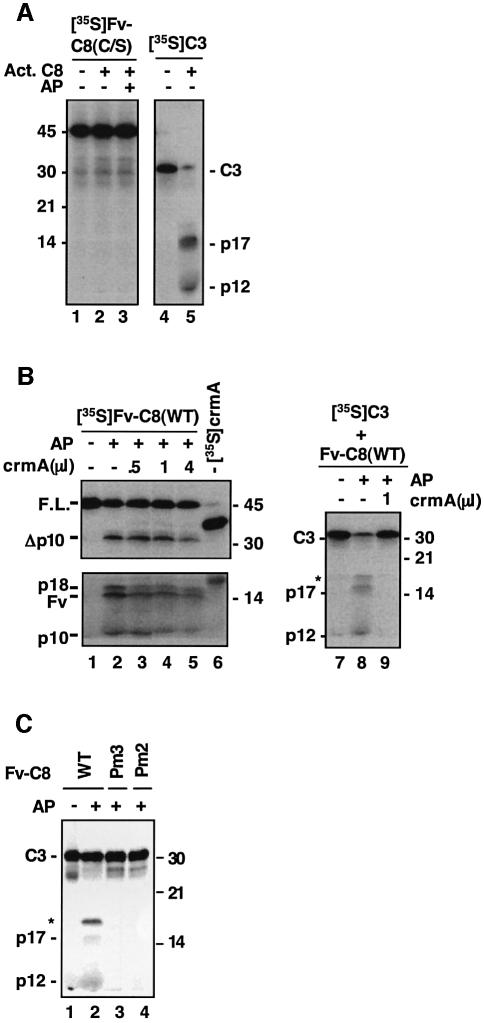

Although procaspase-8 molecules can readily process themselves, mature caspase-8 molecules cannot process their monomeric precursors (Medema et al., 1997; Kischkel et al., 2001). To determine whether this was due to the lack of dimerization of procaspase-8, we used mature caspase-8 to treat Fv-C8(C/S). No cleavage of Fv-C8(C/S) was observed regardless of whether AP20187 was added (Figure 6A, lanes 2 and 3 versus lane 1), although the same amount of mature caspase-8 processed procaspase-3 to near completion (Figure 6A, lane 5). Similarly, mature caspase-8 failed to process the procaspase-8 molecules in the DISC (data not shown). We next tested the effect of crmA, a potent inhibitor of mature caspase-8, on the AP20187-induced activation of Fv-C8(WT). crmA had only a minimal inhibitory effect on the activation process (Figure 6B, lanes 3–5 versus lane 2), even though it almost completely blocked the ability of the mature caspase-8 to cleave caspase-3 (lane 9 versus lane 8). Thus, the substrate specificities of the precursor and mature caspase-8 molecules appear to be different. To examine this possibility further, we tested the non-processible mutants (Pm2 and Pm3) for cleavage of caspase-3. Neither in vitro translated nor recombinant Fv-C8(Pm2) and Fv-C8(Pm3) could cleave caspase-3 (Figure 6C, lanes 3 and 4; data not shown), while Fv-C8(WT) could, as predicted. Together, these results show that the active procaspase-8 and mature caspase-8 proteins have distinct enzymatic characteristics. While the procaspase-8 dimers cleave one another but not effector procaspases, the mature caspase-8 molecules process effector procaspases but not their own precursors.

Fig. 6. Change of enzymatic characteristics during the activation of procaspase-8. (A) Individual and dimerized caspase-8 precursors cannot be processed by mature caspase-8. [35S]Fv-C8(C/S) or [35S]procaspase-3 (C3) was treated with active caspase-8 (20 ng/µl) and AP20187 as indicated. p17 and p12 are the large and small subunits of mature caspase-3, respectively. (B) The precursor and mature caspase-8 have different substrate specificities. Left panel: lanes 1–5, 1 µl of [35S]Fv-C8(C/S) was treated with AP20187 in the presence of the indicated amount of non-radiolabeled crmA; lane 6 contained 1 µl of 35S-labeled crmA to show the level of protein expression. Right panel: 1 µl of [35S]C3 was treated with Fv-C8 that had been previously treated with AP20187 (+) or with vehicle (–); 1 µl of crmA was included in the reaction as indicated. The asterisk indicates a band containing both the large subunit and the prodomain of caspase-3. (C) Active caspase-8 precursor does not process caspase-3. [35S]C3 was incubated with Fv-C8 proteins that were either pretreated with AP20187 (+) or untreated (–).

Discussion

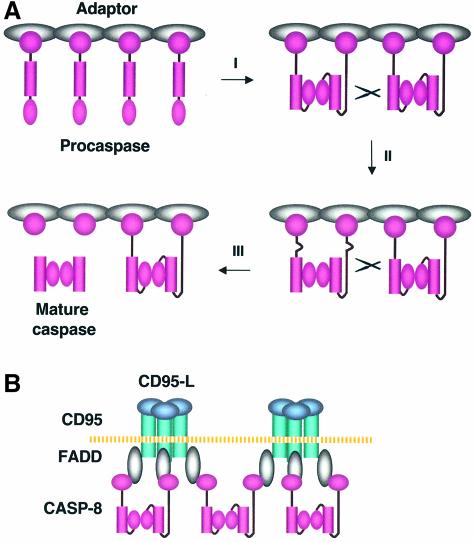

The mechanism of caspase activation is central to understanding apoptosis regulation. Here we propose an ‘interdimer processing’ model for the activation of procaspase-8, a prominent initiator caspase involved in multiple scenarios of apoptosis (Figure 7A). Upon oligomerization, individual procaspase-8 molecules associate with each other through their protease domains to form multiple procaspase dimers (step I). These dimers are not only proteolytically competent, but are also more susceptible to cleavage themselves, which results in their cross-cleavage (step II). Procaspase-8 activation involves two cleavage events: the separation of the large and small subunits, followed by the separation of the large subunit and prodomain. The order is maintained by a sequential accessibility mechanism; the region between the prodomain and large subunit is not susceptible to cleavage until the large and small subunits are separated (step III). Finally, during the activation process, caspase-8 undergoes a change in substrate specificity. While the precursor dimers specifically recognize one another, mature caspase-8 only activates the precursors of effector caspases.

Fig. 7. The ‘interdimer processing’ model for procaspase-8 activation. (A) Upon adaptor-mediated oligomerization, procaspase–8 molecules in the DISC form dimers through a stable interaction between their protease domains to become proteolytically active (I). These dimers are also susceptible to cleavage by other procaspase-8 dimers at the region linking the large and small subunits (II). The severance of the large and small subunits leads to a conformational change in the region between the prodomain and the large subunit, allowing this region to be subsequently cleaved. The resulting mature caspase-8 is released to the cytosol (III). (B) While two procaspase-8 molecules within a DISC complex form a dimer, the third one may associate with the unpaired caspase-8 from another DISC, allowing the appropriate alignment of these intermediates to facilitate cross-cleavage between the dimers.

Interdimer processing model of procaspase-8 activation

Recently, we and others have shown that the activation of procaspase-9, an initiator procaspase linked to the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway, requires homophilic interaction of its protease domain (Boatright et al., 2003; Chang et al., 2003), and others have reported that procaspase-8 forms dimers that are enzymatically active (Chen et al., 2002; Boatright et al., 2003; Donepudi et al., 2003). Here, by using an inducible system for caspase-8 activation, in combination with extensive mutagenesis as well as analyses of the full-length wild-type and mutant caspase-8 proteins in the endogenous DISC complex and during anti-APO-1-induced apoptosis, we demonstrate the physiological relevance of the dimerization-induced activity of procaspase-8. Necessary formation of an active intermediate by two precursor molecules distinguishes procaspase activation from the well-studied activation of receptor tyrosine kinases, even though both are mediated by induced proximity. Because the formation of a dimeric procaspase-8 intermediate does not require both partners to possess enzymatic activity, a catalytic mutant that can still associate with the wild-type protein [e.g. Fv-C8(C/S)] may not have a strong dominant-negative effect upon Fv-mediated heterodimerization, while mutants that do not have an intact protease domain (e.g. Fv-C8Δ) can potently inhibit caspase activation (Figure 1D). This unique mechanism of procaspase-8 activation allows for an intriguing mode of regulation: it can be both positively and negatively regulated by a proteolytically inactive caspase homolog c-FLIPL. At high levels of expression, c-FLIPL competes with caspase-8 for recruitment to the DISC, thereby inhibiting caspase-8 activation. However, at low levels of expression, c-FLIPL promotes caspase-8 activation through its protease-like domain, which strongly induces enzymatic activity in procaspase-8 via direct protein–protein interactions (Chang et al., 2002).

Interestingly, procaspase-8 dimers are preferred substrates for one another. A cardinal feature for the mechanism that controls the activation of the deadly and irreversible caspase cascade is to minimize the chance of accidental activation in healthy cells while still enabling massive activation when needed. The interdimer cleavage mechanism provides a remarkably simple way to achieve both safety and effectiveness for caspase activation. Because a procaspase dimer, rather than an individual procaspase molecule, has proteolytic activity, the possibility of accidental caspase activation is decreased. In addition, even if a procaspase dimer is formed by chance, it would have to encounter another dimer to trigger processing, further decreasing the possibility of spurious activation. On the other hand, the oligomerization of procaspases that occurs endogenously during apoptosis leads to the generation of multiple procaspase dimers in close proximity. With these dimers serving as both enzymes and substrates for one another, massive caspase activation can occur in a short period of time to ensure the demise of cells. The interdimer processing model represents not only a novel mechanism for the regulation of proteases, but also a new paradigm for oligomerization-induced signal transduction.

In death receptor-mediated apoptosis, the trimeric state of ligands theoretically enables up to three caspase-8 molecules to exist in the same DISC complex. However, two or more death receptor complexes need to be brought into close proximity to trigger cell death effectively (Kischkel et al., 1995). The cross-cleavage of precursor dimers explains why a higher order of procaspase-8 oligomerization is needed to induce apoptosis. Moreover, it is interesting to speculate that the function of the third procaspase-8 molecule in the DISC complex is to associate with another undimerized procaspase-8 molecule in an adjacent DISC complex, facilitating the proper alignment of procaspase-8 dimers for cross-cleavage (Figure 7B).

Maintenance of the order of cleavage events for the generation of mature caspase-8

Following the separation of the large and small subunits, the region linking the large subunit and the prodomain in procaspase-8 is cleaved. This two-step cleavage process for activation is shared by most caspases. It is imperative that the order of the cleavage events be enforced to ensure that fully processed caspase molecules, rather than partially processed molecules, are released from procaspase-activating complexes. In the case of caspase-8, because ligand-engaged DISC complexes are eventually internalized via the endosomal pathway (Algeciras-Schimnich et al., 2002), the release of mature caspase-8 also prevents it from being degraded. By using a non-processible mutant as well as introducing a heterologous cleavage site into procaspase-8, we have demonstrated a sequential accessibility mechanism that accounts for the ordered occurrence of the cleavage events (Figure 5).

Different substrate specificity of procaspase-8 and mature caspase-8

We have shown that procaspase-8 and mature caspase-8 have different enzymatic characteristics, which may have important implications. First, the inability of mature caspase-8 to process its own precursor suggests that the activation of initiator procaspases may be a limited event and may not trigger cell death under certain circumstances. To generate large amounts of initiator caspases for apoptosis induction, a prolonged presence of an apoptotic stimulus may be required. Alternatively, initiator procaspases may need to be further processed by mature effector caspases, creating a positive feedback loop, as exemplified by the processing of procaspase-9 by mature caspase-3 (Srinivasula et al., 1998). The limited activation of initiator caspases would thus allow for additional levels of apoptosis regulation.

Secondly, the different substrate specificities of procaspase-8 and mature caspase-8 may explain the paradoxical observation that caspase-8 is also required for cell proliferation. We propose a model in which the state of procaspase-8 oligomerization determines the fate of cells: higher orders of clustering may cause the complete processing of caspase-8 and the subsequent massive activation of effector caspases, ensuring the demise of the cell, while lower orders of clustering may cause only transient activation of procaspase-8 at the precursor level, which could disseminate a proliferative signal. Although overexpression of non-processible procaspase-8 mutants can kill cells (Figure 2E and F), the active procaspase-8 in the DISC may be subjected to downregulation through mechanisms such as the rapid internalization of the DISC complex. Consistent with our model are the different effects that crmA has on caspase-8 activation and cell fate. crmA has been shown to inhibit active caspase-8 and apoptosis but to have no effect on the processing of DISC-bound procaspase-8 (Medema et al., 1997). We show here that crmA does not inhibit the activation of procaspase-8. While T cells lacking caspase-8 activity fail to generate interleukin 2 and proliferate (Chun et al., 2002; Salmena et al., 2003), mice expressing crmA as a transgene in T cells do not manifest any defects in T-cell proliferation (Smith et al., 1996). Thus, we predict that it is not the activity of the DISC-released crmA-sensitive mature caspase-8 enzyme but rather the activity of the crmA-resistant active procaspase-8 that regulates T-cell proliferation.

Finally, as enzymes and as critical components for cell death, caspases are attractive targets for the therapeutic intervention of diseases associated with increased apoptosis, such as neurodegeneration and immunodeficiency (Nicholson, 2000). However, given that caspase-8 is also essential for cell proliferation, unselective inhibition of the activities of caspases may have detrimental effects. The possible differences in enzymatic properties between precursor and mature caspases should be explored to achieve a more potent and specific inhibition of apoptosis without affecting other cellular functions.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and reagents

The monoclonal antibodies against CD95 (anti-APO-1) and caspase-8 (C15) have been described previously (Scaffidi et al., 1999). The following reagents were obtained from the indicated sources: AP20187 and AP1510 (ARIAD Pharmaceuticals); biotin-VAD-fmk, Z-VAD-fmk, horseradish peroxidase–avidin (HRP–avidin) and Ac-IETD-AFC (Enzyme System Products); protein A–agarose (Life Technologies); Thrombin (Novagen); active caspase-8 (PharMingen); annexin V conjugated with phycoerythrin (Caltag); anti-(His)6 probe (H-15; Santa Cruz); and anti-FLAG M2–agarose beads (Sigma).

Expression constructs

Constructs for expression in mammalian cells and for in vitro translation were made in pRK5. Full-length caspase-8 proteins were fused with an HA tag at the N-terminus and with a FLAG tag at the C-terminus. The caspase-8 protein domains were tagged with six histidines at the N-terminus and with either a FLAG or an HA epitope at the COOH terminus, as indicated. Fv fusions of full-length caspase-8 and of the caspase-8 protease domain contained the c-Src myristoylation signal at the N-terminus for membrane targeting, a FLAG epitope tag at the C-terminus for protein detection and an HA tag (for the full-length caspase-8 fusions) or a five amino acid stretch (GGGGS) (for the caspase-8 protease domain fusions) between the Fv domain and the caspase-8 sequence to provide a flexible linker (Chang and Yang, 2003). The FKBP fusions of full-length caspase-8 and caspase-8 protease domain and the Fv fusion of c-FLIP were described previously (Yang et al., 1998a; Chang et al., 2002). Bacterial expression plasmids were made in pET28a (Novagen) with a C-terminal His6 tag. All point mutations were generated by overlap PCR and confirmed by sequencing. The caspase-8Δ mutation was generated by digesting the wild-type caspase-8 plasmids with AccI and XhoI and religating the plasmid. The Ala397 to Val mutation was identified through screening for non-processible mutants of the Fv-C8(WT) clones that were generated through PCR mutagenesis. Fv-C8(C/S, Pm2, Trb) contained the Cys360 to Ser mutation and the Asp374, 384 to Asp mutations, as well as a thrombin cleavage site LVPR↓GS to replace 377EQPYLE of caspase-8.

In vitro caspase-8 processing

Processing of Fv-caspase-8 proteins was performed essentially as described (Chang et al., 2002, 2003; Chang and Yang, 2003). When in vitro translated non-radiolabeled proteins were included, the total amounts of in vitro translation mix among different reactions were made constant by using the translation mix containing no DNA. The reaction was performed at 30°C for 4 h in the presence of 100 nM AP20187 unless indicated otherwise.

Cell death assay

HeLa cells seeded were transfected with Fv-caspase-8 plasmids or the full-length caspase-8 plus pEGFP-N3 (Clontech). The percentage of apoptosis was determined as described previously (Yang et al., 1998b). Caspase-8-deficient Jurkat cells (1 × 106) were transfected with 1 µg of full-length caspase-8 constructs plus 2 µg of pEGFP-N3 via Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) mediated gene transfer. After 18 h, the cells were treated with protein A (100 ng/ml) only or protein A plus anti-CD95 (1 µg/ml) for 20 h. Apoptosis among GFP-positive cells was analyzed by staining cells with annexin V on a FACScan using CELLQuest software (Becton-Dickinson).

Purification of Fv-C8 proteins and assay of caspase-8 activity

His6-tagged Fv-caspase-8 proteins were expressed in BL21 (DE3, LysS) cells and purified sequentially by a Ni-NTA column and a DEAE–Sepharose column. Caspase-8 activity was assayed using either a fluorogenic substrate IETD-AFC or a biotinylated VAD-fmk for labeling, as described (Chang et al., 2002).

DISC analysis and processing of caspase-8 by DISC

Immunoprecipitation of the CD95 DISC complex was carried out essentially as described (Scaffidi et al., 1999). To label enzymatically active products, the DISC complex was incubated with 100 µM biotinylated VAD-fmk in MDB buffer (Chang et al., 2002) in the presence or absence of the indicated amounts of non-biotinylated z-VAD-fmk. To label the cytosolic fraction, cell lysate from 1 × 107 SKW6.4 cells was incubated with 100 µM of biotinylated VAD-fmk in MDB buffer. For an in vitro cleavage assay, 10 µl of the CD95 complex from either anti-CD9-treated or untreated cells were incubated with 1 µl of in vitro translated 35S-labeled full-length caspase-8 in 30 µl of caspase assay buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.2, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% sucrose, 0.1% CHAPS, 0.3 mM dithiothreitol) for 18–20 h at 4°C.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank L.Gardner and R.Stratt for technical assistance, R.Stratt for excellent help with the manuscript preparation, Dr J.Blenis for the caspase-8-deficient cells, Dr S.Hu for reagents and ARIAD Pharmaceuticals for the FKBP dimerization system. D.W.C. was a postdoctoral appointee of an NCI training grant T32CA09140. This work was supported by NIH grants GM60911 and CA88868 to X.Y. and GM61712 to M.E.P.

References

- Algeciras-Schimnich A., Shen,L., Barnhart,B.C., Murmann,A.E., Burkhardt,J.K. and Peter,M.E. (2002) Molecular ordering of the initial signaling events of CD95. Mol. Cell. Biol., 22, 207–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi A. and Dixit,V.M. (1998) Death receptors: signaling and modulation. Science, 281, 1305–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard H., Donepudi,M., Tschopp,M., Kodandapani,L., Wu,J.C. and Grutter,M.G. (2000) Caspase-8 specificity probed at subsite S(4): crystal structure of the caspase-8-Z-DEVD-CHO complex. J. Mol. Biol., 302, 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boatright K.M. et al. (2003) A unified model for apical caspase activation. Mol. Cell, 11, 529–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang D.W. and Yang,X. (2003) Activation of procaspases by FK506 binding protein-mediated oligomerization. Sci. STKE, 2003, PL1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang D.W., Xing,Z., Pan,Y., Algeciras-Schimnich,A., Barnhart,B.C., Yaish-Ohad,S., Peter,M.E. and Yang,X. (2002) c-FLIP(L) is a dual function regulator for caspase-8 activation and CD95-mediated apoptosis. EMBO J., 21, 3704–3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang D.W., Ditsworth,D., Liu,H., Srinivasula,S.M., Alnemri,E.S. and Yang,X. (2003) Oligomerization is a general mechanism for the activation of apoptosis initiator and inflammatory procaspases. J. Biol. Chem., 278, 16466–16469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H.Y. and Yang,X. (2000) Proteases for cell suicide: functions and regulation of caspases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 64, 821–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Orozco,A., Spencer,D.M. and Wang,J. (2002) Activation of initiator caspases through a stable dimeric intermediate. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 50761–50767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun H.J. et al. (2002) Pleiotropic defects in lymphocyte activation caused by caspase-8 mutations lead to human immunodeficiency. Nature, 419, 395–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clackson T. et al. (1998) Redesigning an FKBP-ligand interface to generate chemical dimerizers with novel specificity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 10437–10442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donepudi M., Sweeney,A.M., Briand,C. and Grutter,M.G. (2003) Insights into the regulatory mechanism for caspase-8 activation. Mol. Cell, 11, 543–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw W.C., Martins,L.M. and Kaufmann,S.H. (1999) Mammalian caspases: structure, activation, substrates and functions during apoptosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 68, 383–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervais F.G. et al. (2002) Recruitment and activation of caspase-8 by the Huntingtin-interacting protein Hip-1 and a novel partner Hippi. Nat. Cell Biol., 4, 95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengartner M.O. (2000) The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature, 407, 770–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juo P., Kuo,C.J., Yuan,J. and Blenis,J. (1998) Essential requirement for caspase-8/FLICE in the initiation of the Fas-induced apoptotic cascade. Curr. Biol., 8, 1001–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kischkel F.C., Hellbardt,S.H., Behrmann,I., Germer,M., Pawlita,M., Krammer,P.H. and Peter,M.E. (1995) Cytotoxicity-dependent APO-1 (Fas/CD-95)-associated proteins form a death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) with the receptor. EMBO J., 14, 5579–5588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kischkel F.C. et al. (2001) Death receptor recruitment of endogenous caspase-10 and apoptosis initiation in the absence of caspase-8. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 46639–46646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krammer P.H. (2000) CD95’s deadly mission in the immune system. Nature, 407, 789–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D.A., Siegel,R.M., Zheng,L. and Lenardo,M.J. (1998) Membrane oligomerization and cleavage activates the caspase-8 (FLICE/MACHα1) death signal. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 4345–4349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medema J.P., Scaffidi,C., Kischkel,F.C., Shevchenko,A., Mann,M., Krammer,P.H. and Peter,M.E. (1997) FLICE is activated by association with the CD95 death-inducing signaling complex (DISC). EMBO J., 16, 2794–2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheau O., Thome,M., Schneider,P., Holler,N., Tschopp,J., Nicholson,D.W., Briand,C. and Grutter,M.G. (2002) The long form of FLIP is an activator of caspase-8 at the Fas death-inducing signaling complex. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 45162–45171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzio M., Stockwell,B.R., Stennicke,H.R., Salvesen,G.S. and Dixit,V.M. (1998) An induced proximity model of caspase-8 activation. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 2926–2930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson D.W. (1999) Caspase structure, proteolytic substrates and function during apoptotic cell death. Cell Death Differ., 6, 1028–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson D.W. (2000) From bench to clinic with apoptosis-based therapeutic agents. Nature, 407, 810–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter M.E., Scaffidi,C., Medema,J.P., Kischkel,F. and Krammer,P.H. (1998) The death receptors. In Kumar,S. (ed.), Apoptosis: Biology and Mechanisms. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany, pp. 25–63. [Google Scholar]

- Salmena L. et al. (2003) Essential role for caspase 8 in T-cell homeostasis and T-cell-mediated immunity. Genes Dev., 17, 883–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvesen G.S. and Dixit,V.M. (1999) Caspase activation: the induced-proximity model. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 10964–10967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez I., Xu,C.-J., Juo,P., Kakizaka,A., Blenis,J. and Yuan,J. (1999) Caspase-8 is required for cell death induced by expanded polyglutamine repeats. Neuron, 22, 623–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaffidi C., Schmitz,I., Krammer,P.H. and Peter,M.E. (1999) The role of c-FLIP in modulation of CD95-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 1541–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlessinger J. (2000) Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell, 103, 211–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R.M., Chan,F.K., Chun,H.J. and Lenardo,M.J. (2000) The multifaceted role of Fas signaling in immune cell homeostasis and autoimmunity. Nat. Immunol., 1, 469–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K.G., Strasser,A. and Vaux,D.L. (1996) CrmA expression in T lymphocytes of transgenic mice inhibits CD95 (Fas/APO-1)-transduced apoptosis, but does not cause lymphadenopathy or autoimmune disease. EMBO J., 15, 5167–5176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasula S.M., Ahmad,M., Fernandes-Alnemri,T. and Alnemri,E.S. (1998) Autoactivation of procaspase-9 by Apaf-1-mediated oligomerization. Mol. Cell, 1, 949–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry N.A. and Lazebnik,Y. (1998) Caspases: enemies within. Science, 281, 1312–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varfolomeev E.E. et al. (1998) Targeted disruption of the mouse caspase 8 gene ablates cell death induction by the TNF receptors, Fas/Apo1 and DR3 and is lethal prenatally. Immunity, 9, 267–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wajant H. (2002) The Fas signaling pathway: more than a paradigm. Science, 296, 1635–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt W., Koeplinger,K.A., Mildner,A.M., Heinrikson,R.L., Tomasselli,A.G. and Watenpaugh,K.D. (1999) The atomic-resolution structure of human caspase-8, a key activator of apoptosis. Structure Fold Des., 7, 1135–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Chang,H.Y. and Baltimore,D. (1998a) Autoproteolytic activation of pro-caspases by oligomerization. Mol. Cell, 1, 319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Chang,H.Y. and Baltimore,D. (1998b) Essential role of CED-4 oligomerization in CED-3 activation and apoptosis. Science, 281, 1355–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]