Abstract

In the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942, circadian timing is transmitted from the KaiABC-based central oscillator to the transcription factor RpaA via the KaiC-interacting histidine kinase SasA to activate transcription, thereby generating rhythmic circadian gene expression. However, KaiC can also repress circadian gene expression, including its own. The mechanism and significance of this negative feedback regulation have been unclear. Here, we report a novel gene, labA (low-amplitude and bright), that is required for negative feedback regulation of KaiC. Disruption of labA abolished transcriptional repression caused by overexpression of KaiC and elevated the trough levels of circadian gene expression, resulting in a low-amplitude phenotype. In contrast, overexpression of labA significantly lowered circadian gene expression. Furthermore, genetic analysis indicated that labA and sasA function in parallel pathways to regulate kaiBC expression, whereas rpaA functions downstream from labA for kaiBC expression. These results suggest that temporal information from the KaiABC-based oscillator diverges into a LabA-dependent negative pathway and a SasA-dependent positive pathway, and then converges onto RpaA to generate robust circadian gene expression. It is likely that quantitative information of KaiC is transmitted to RpaA through LabA, whereas SasA mediates the state of the KaiABC-based oscillator.

Keywords: Circadian clock, cyanobacteria, KaiC, labA, RpaA, SasA

The circadian clock is an endogenous timing system that controls various biological activities with a period of ∼24 h. Most organisms use self-sustained oscillation to coordinate with and adapt to daily environmental changes. KaiA, KaiB, and KaiC have been identified as essential components for circadian oscillation in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 (hereafter Synechococcus). KaiC, an autokinase and autophosphatase, is the central component of the cyanobacterial circadian clock and interacts with KaiA and KaiB (Ishiura et al. 1998; Iwasaki et al. 1999; Nishiwaki et al. 2000; Taniguchi et al. 2001). KaiA enhances the autokinase activity of KaiC (Iwasaki et al. 2002; Williams et al. 2002; Uzumaki et al. 2004) and/or inhibits its autophosphatase activity (Kitayama et al. 2003; Xu et al. 2003), while KaiB attenuates the activity of KaiA (Williams et al. 2002; Kitayama et al. 2003; Xu et al. 2003). KaiC phosphorylation oscillates with a period of ∼24 h when the three recombinant Kai proteins are incubated in vitro in the presence of ATP (Nakajima et al. 2005). This oscillation period is refractory to changes in temperature, an important feature of circadian rhythms (Nakajima et al. 2005). Thus, Kai-based chemical oscillation is thought to be the basic circadian timing loop in Synechococcus (Nakajima et al. 2005; Tomita et al. 2005).

KaiC also interacts with a sensory histidine kinase, SasA (Iwasaki et al. 2000). Autophosphorylation of SasA is enhanced in response to KaiC binding (Smith and Williams 2006; Takai et al. 2006), and this phosphate group is then transferred to the putative DNA-binding protein RpaA (Takai et al. 2006). Inactivation of either sasA or rpaA dramatically reduces circadian gene expression (Iwasaki et al. 2000; Takai et al. 2006). Thus, the KaiC–SasA–RpaA pathway is likely to be a major positive pathway for circadian gene expression (Takai et al. 2006).

Notably, overexpression of KaiC strongly represses its own expression in a dose-dependent manner (negative feedback regulation) (Ishiura et al. 1998; Nishiwaki et al. 2004). In addition, most promoters in Synechococcus are clock-controlled (Liu et al. 1995) and are repressed to trough levels by KaiC overexpression (Nakahira et al. 2004). Transcriptional and translational oscillatory (TTO) processes involving negative feedback regulation of clock genes are thought to be essential for generating the basic circadian timing loop in most model organisms. In Synechococcus, negative feedback regulation of KaiC is important for circadian clock function, even though TTO processes are not necessary for circadian oscillation of KaiC phosphorylation (Nakajima et al. 2005; Tomita et al. 2005). It is thought that coupling of the KaiC phosphorylation cycle and the transcription–translation feedback process amplifies and stabilizes oscillation and mediates rhythmic physiological outputs (Tomita et al. 2005). However, the significance of negative feedback regulation of KaiC in the cyanobacterial circadian clock system has not been fully evaluated, because the mechanism of this feedback regulation is still unclear.

Here, we report a novel gene called labA (low-amplitude and bright) that is required for negative feedback regulation of KaiC. We demonstrate that labA and sasA cooperatively modulate rpaA function and cellular metabolism. In addition, we discuss the physiological roles of feedback regulation of KaiC in the cyanobacterial circadian clock system.

Results

Identification of a novel gene required for negative feedback regulation of KaiC

We previously generated transgenic Synechococcus reporter strains in which the Vibrio harveyi luciferase gene was placed under the control of the kaiBC promoter (PkaiBC∷luxAB) and kaiC was placed under the control of an isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible promoter (Ptrc∷kaiC) (Ishiura et al. 1998; Iwasaki et al. 2002; Nakahira et al. 2004). In these strains, continuous IPTG-induced overexpression of kaiC results in complete repression of luciferase expression via negative feedback inhibition of the kaiBC promoter (Fig. 1A; Ishiura et al. 1998; Iwasaki et al. 2002; Nakahira et al. 2004).

Figure 1.

Identification of labA as a gene required for negative feedback regulation of KaiC. (A) Bioluminescence traces of labA mutants in the kaiC-overexpressing PkaiBC∷luxAB reporter strain. Cells were grown on agar plates, and their bioluminescence rhythms were measured under LL after entrainment with two LD cycles. IPTG (1 mM) or water was added at hour 24 in LL (LL 24). (Top panel) Bioluminescence rhythm of the parental reporter strain OX-kaiC(Ω)/NUC42. (Middle panel) Original labA mutant (Mutant 1) isolated from screen. (Bottom panel) labA mutant generated using pDlabA(Kmr) [OX-kaiC(Ω)/labA−(Km)/NUC42]. (Red trace) Bioluminescence of cells treated with 1 mM IPTG; (black trace) bioluminescence of cells treated with water. The arrow indicates the timing of the addition of IPTG (or water). (B) Nucleotide sequence around the labA locus and deduced amino acid sequence of LabA. Transposon insertion sites of the three original mutants (Mutant 1–Mutant 3) are underlined (the transposon insertion created a 9-bp target site sequence duplication). The HpaI site used to generate pDlabA(Kmr) or pDlabA(Ω) is boxed (see Materials and Methods). The arrow indicates the start site of the downstream ORF, Synpcc7942_1892/syc2203_c. (C) Sequence comparison of LabA and LabA-related proteins from cyanobacterial species (PCC 7942, S. elongatus PCC 7942; PCC 7120, Nostoc sp. PCC 7120; PCC 7421, Gloeobacter violaceus PCC 7421; PCC 6803, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803; BP-1, Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1).

To identify novel factors involved in the negative feedback regulation of KaiC, we searched for mutants that were defective in their PkaiBC∷luxAB reporter gene response to overexpression of KaiC. We randomly mutagenized the PkaiBC∷luxAB reporter strain carrying the Ptrc∷kaiC transgene [OX-kaiC(Ω)/NUC42] by transposon insertion and monitored the bioluminescence of individual colonies of transformants in the presence of IPTG. We screened ∼20,000 colonies and isolated three independent mutants that expressed the luxAB reporter gene even in the presence of IPTG. In these mutants, KaiC was overexpressed at high enough levels to disturb circadian rhythms, but the level of bioluminescence progressively increased and remained elevated, suggesting that feedback regulation of KaiC was abolished (Fig. 1A). In the absence of IPTG, mutants showed moderate, low-amplitude rhythms with higher trough levels of bioluminescence (Fig. 1A). Moreover, the average bioluminescence intensity of the mutant lines was 10–20 times higher than that of the parental reporter strain (“bright” phenotype) (Fig. 1A).

To determine what genes were altered in these mutants, we recovered kanamycin-resistant genomic fragments from mutant cells, and DNA regions flanking the transposons were sequenced. The three mutants carried independent transposon insertions in the same 561-base-pair (bp) putative ORF encoding a conserved hypothetical protein (locus tag; Synpcc7942_1891/Syc2204_c) with no known functional motifs or domains (Fig. 1B). We confirmed that the mutant phenotype could be reproduced by inserting a kanamycin resistance gene cassette (Kmr) into the HpaI site of the ORF [OX-kaiC(Ω)/labA−(Km)/NUC42] (Fig. 1A,B). We named this gene labA after the phenotype of the mutants. LabA-related protein sequences are found not only in cyanobacteria (Fig. 1C), but also in various prokaryotic organisms, including some archaea (Supplementary Fig. S1A).

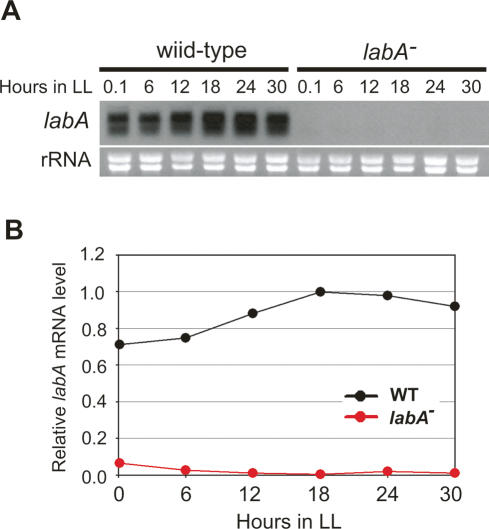

We next examined the levels of labA transcript in a wild-type PkaiBC∷luxAB reporter strain (NUC42) by Northern blotting (Fig. 2). As a negative control, we constructed a labA mutant without the Ptrc∷kaiC transgene [labA−(Km)/NUC42] by transforming NUC42 with pDlabA(Kmr). After release from a 12-h dark period, labA transcripts accumulated gradually under continuous light exposure (LL 0.1–18) and plateaued after LL 18, whereas no transcript was detected in the labA mutant (Fig. 2). These results suggest that the accumulation of labA transcripts showed little rhythmicity.

Figure 2.

Identification of labA transcripts. (A) NUC42 (wild-type) and labA-disrupted NUC42 [labA−(Km)/NUC42] strains were cultured in BG-11M medium, and cells were collected every 6 h after entrainment with LD cycles. Total RNA (5 μg) was separated by electrophoresis, and labA transcript was detected by Northern blotting using a DIG-labeled labA-specific probe. An image of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) stained with ethidium bromide is shown in parallel. (B) Densitometric data of the blot are also shown.

Characterization of labA mutant

To confirm that the “low-amplitude and bright” phenotype was not caused by the presence of the Ptrc∷kaiC transgene, we monitored the bioluminescence rhythm of labA−(Km)/NUC42 cells (Supplementary Fig. S2A). Disruption of labA increased the trough levels of bioluminescence, resulting in a low-amplitude rhythm with broad peaks (Supplementary Fig. S2A). In addition, the maximum bioluminescence intensity in the labA mutant was about sevenfold higher than that of the parental wild-type reporter strain (Supplementary Fig. S2A). These results demonstrate that the phenotype we observed in labA mutants was independent of the Ptrc∷kaiC transgene.

To evaluate whether or not loss of labA affects expression at other promoters, we inactivated labA in the PpsbAI∷luxAB reporter strain AMC149 (Kondo et al. 1993). psbAI encodes a photosystem II protein, and its promoter drives expression with a robust circadian rhythm (Fig. 3A; Kondo et al. 1993). We found that labA mutants on an AMC149 background [labA−(Km)/AMC149] exhibited a severe, low-amplitude rhythm with distorted waveforms, and the maximum bioluminescence intensity of the labA mutant was ∼12-fold higher than that of the parental wild-type reporter strain (Fig. 3A), indicating that the labA mutation can affect expression at various promoters.

Figure 3.

Characterization of labA mutants generated by pDlabA(Kmr). (A,B) Bioluminescence rhythms of labA mutants. labA was inactivated in PpsbAI∷luxAB (A) or PkaiBC∷luc (B) reporter strains, and bioluminescence was monitored after entrainment with two LD cycles. The red and black traces in each panel show the bioluminescence rhythms of labA mutant and wild-type cells, respectively. (C) Fluctuation of kaiBC transcript in labA mutant [labA−(Km)/NUC42] cells detected by Northern blotting. (Panel a) Samples were prepared as described in Figure 2A except for the additional sampling at LL 9, and kaiBC transcript was detected by Northern blotting using a DIG-labeled kaiBC-specific probe. (Panel b) Densitometric data from three independent experiments. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. (D) Accumulation profile of KaiC protein in the labA mutant [labA−(Km)/NUC42]. Cells were collected as described in Figure 2A, and total cellular proteins were prepared. Two micrograms of total cellular protein were loaded per lane, and KaiC was detected with anti-KaiC antiserum. The upper and lower bands correspond to phosphorylated KaiC (P-KaiC) and nonphosphorylated KaiC (NP-KaiC), respectively. (E) Slow-growth phenotype of the labA mutant. Colonies were grown in LL (40 μE m−2 sec−1) at 30°C for 6 d.

The increased bioluminescence in labA mutants suggested that labA might play a role in bacterial luciferase reactions. To test this possibility, we generated labA mutants in which the firefly luciferase (luc) gene was placed under the control of the PkaiBC promoter (AMC541 strain). Interestingly, the average bioluminescence intensity per colony of labA−(Km)/AMC541 was comparable to that of the parental AMC541 strain, in spite of the fact that disruption of labA caused low-amplitude rhythms with higher trough levels and broader peaks (Fig. 3B). In other words, the bright phenotype of labA was not observed in the AMC541 reporter strain. Similar results were obtained using a railroad-worm luciferase reporter strain, labA−(Km)/PkaiRE (Supplementary Fig. S2B). The bacterial luciferase luxAB requires oxygen, reduced flavin mononucleotide (FMNH2), and n-decanal as substrates to generate bioluminescence, whereas firefly and railroad-worm luciferase require ATP and luciferin instead of FMNH2 and n-decanal. In our experiments, luciferin and n-decanal were provided exogenously, whereas ATP and FMNH2 were derived from endogenous sources. Thus, a plausible explanation for the extreme bright phenotype when bacterial luciferase was used as a reporter is that FMNH2 may accumulate to high levels in the labA mutants, implying that labA may be involved in FMNH2-related metabolism as well as in circadian gene expression. It was previously shown that disruption of opcA, which regulates the level of endogenous FMNH2, affects the bioluminescence rhythm of luxAB reporter strains (Min and Golden 2000). However, since the bioluminescence waveform of labA−(Km)/NUC42 cells was similar to that of labA−(Km)/AMC541 cells (Fig. 3B; Supplementary Fig. S2A), whatever causes the bright phenotype does not affect the bioluminescence waveforms in luxAB reporter strains. The labA mutants also showed a slow-growth phenotype on agar plates (Fig. 3E), suggesting that labA is involved in cellular metabolism. It should be noted that the labA mutant did not exhibit slow growth in liquid culture (data not shown), indicating that this phenotype is dependent on culture conditions. The phenotypes in the mutants were not due to polar effects on the ORF downstream from the labA locus (locus tag; Synpcc7942_1892/syc2203_c) (see also Fig. 1B), because inactivation of Synpcc7942_1892/syc2203_c did not phenocopy our original mutants (data not shown). In addition, transgenic expression of labA in labA mutants was able to rescue the mutant phenotype (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Low-amplitude rhythms were also observed in the labA mutant by Northern blotting for kaiBC transcript (Fig. 3C). The average accumulation level of the kaiBC transcript in the labA mutant was also increased, probably due to the higher trough level of transcriptional oscillation (Fig. 3C). Western blotting confirmed that KaiC was expressed at higher levels in the labA mutant than in wild-type cells, although the circadian phosphorylation–dephosphorylation cycle of KaiC was still sustained in the mutant (Figs. 3D, 5E [below]). These results are consistent with the fact that negative feedback regulation of KaiC was abolished in labA mutants.

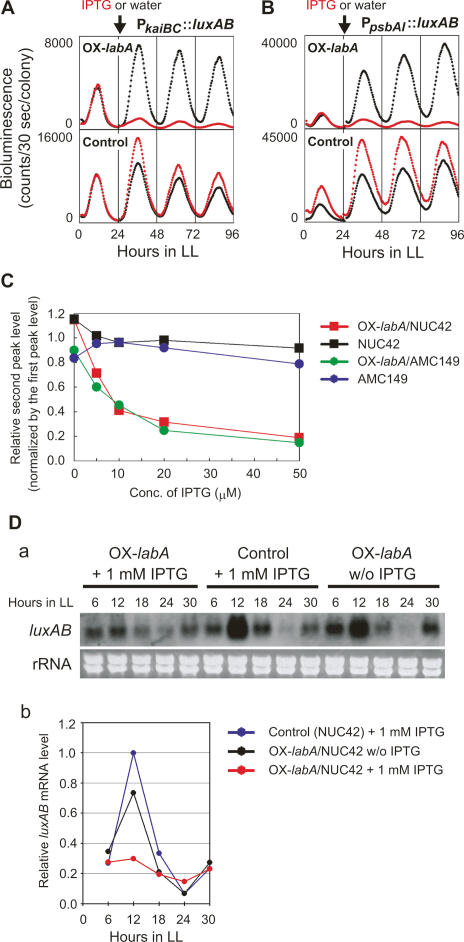

Effects of labA overexpression on circadian gene expression

To further analyze the function of labA, we examined the effect of labA overexpression on circadian gene expression in reporter strains carrying an IPTG-inducible Ptrc∷labA transgene. Overexpression of labA induced by 1 mM IPTG significantly reduced the amplitude of the bioluminescence waveforms in the PkaiBC∷luxAB reporter strain (OX-labA/NUC42) (Fig. 4A). This effect was dose-dependent and did not affect the period of the bioluminescence rhythm (Fig. 4C). Similar results were obtained from experiments with the PpsbAI∷luxAB reporter strain (OX-labA/AMC149) (Fig. 4B,C).

Figure 4.

labA overexpression reduces circadian gene expression. (A–C) Effects of labA overexpression on bioluminescence rhythms of luxAB reporter strains. OX-labA/NUC42 (A), OX-labA/AMC149 (B), and parental reporter strains (Control) were exposed to 1 mM IPTG (red trace) or water (black trace). Arrows indicate the timing of the addition of IPTG (or water). (C) Dose-dependent effects on bioluminescence rhythms in OX-labA/NUC42 and OX-labA/AMC149 reporter strains. Parental strains NUC42 and AMC149 were assayed in parallel. Bioluminescence rhythm was monitored in LL after entrainment with two LD cycles, and various concentrations of IPTG were added to samples around LL 24. The bioluminescence intensity of the second peak (just following IPTG addition) was normalized with that of the first peak (before IPTG treatment), and the ratio value (relative second peak level) was plotted. (D) Expression of the luxAB reporter gene in OX-labA/NUC42. (Panel a) OX-labA/NUC42 and control NUC42 cells were cultured with or without 1 mM IPTG and sampled every 6 h. Five micrograms of total RNA were loaded per lane, and luxAB transcript was directly detected by Northern blotting using a DIG-labeled luxAB-specific probe. Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) stained with ethidium bromide is shown in parallel. (Panel b) Densitometric data of the blot are also shown.

To confirm that labA overexpression lowers the reporter gene expression, we examined the expression level of luxAB transcripts in OX-labA/NUC42 by Northern blotting. Cells were cultured in BG-11M liquid medium with or without 1 mM IPTG and sampled after entrainment by 12 h light/12 h dark (LD) cycles. The transcript of luxAB was subsequently detected by using a luxAB-specific probe. IPTG-induced overexpression of labA reduced expression of luxAB transcript, but the circadian oscillation of luxAB transcript was sustained (Fig. 4D). These results are consistent with those shown in Figure 4A, suggesting that labA represses circadian gene expression in a dose-dependent manner.

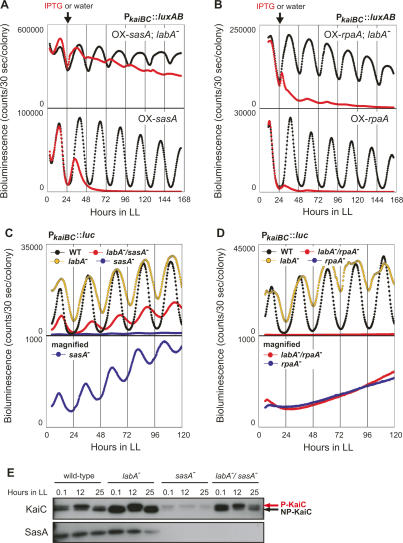

Cooperative modulation of circadian gene expression by labA and sasA through rpaA

The KaiC-interacting sensory histidine kinase SasA and its cognate response regulator RpaA are involved in the output pathways of the cyanobacterial circadian clock (Iwasaki et al. 2000; Takai et al. 2006). Inactivation of either sasA or rpaA dramatically decreases circadian gene expression (Fig. 5C,D; Iwasaki et al. 2000; Takai et al. 2006), indicating their positive regulatory roles in circadian gene expression. However, continuous overexpression of either sasA or rpaA also repressed kaiBC expression (Fig. 5A,B; Iwasaki et al. 2000). To assess whether mutations in labA affect transcriptional repression by sasA or rpaA, we generated labA mutants carrying the PkaiBC∷luxAB reporter and either the Ptrc∷sasA (OX-sasA/NUC42) or Ptrc∷rpaA transgene (OX-rpaA/NUC42) and monitored their bioluminescence rhythms in the presence of 1 mM IPTG. As shown in Figure 5A, loss of labA function attenuated (not abolished) the negative effect of sasA overexpression, suggesting the additive effect of labA and sasA. However, this labA disruption did not substantially affect the negative effect of rpaA overexpression (Fig. 5B).

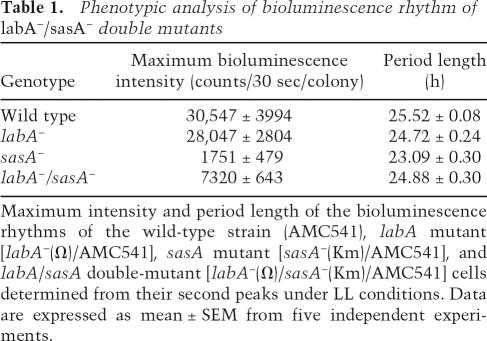

To further investigate the relationship between LabA and the SasA–RpaA pathway, we generated labA/sasA or labA/rpaA double mutants on a PkaiBC∷luc (AMC541) background. The sasA single mutant [sasA−(Km)/AMC541] exhibited a low-amplitude and short-period phenotype, as previously described (Fig. 5C; Table 1; Iwasaki et al. 2000). However, the level of the bioluminescence of the labA/sasA double mutant [labA−(Ω)/sasA−(Km)/AMC541] was significantly higher than that of sasA single mutants [sasA−(Km)/AMC541] and lower than that of labA single mutants [labA−(Ω)/AMC541], indicating that the labA mutation suppressed the low-amplitude phenotype of the sasA mutant (Fig. 5C; Table 1). The level of KaiC protein was also examined by Western blotting analysis (Fig. 5E). In the sasA mutant [sasA−(Km)/AMC541], the level of KaiC was significantly reduced, as previously reported (Fig. 5E; Iwasaki et al. 2000; Takai et al. 2006). In the labA/sasA double mutant [labA−(Ω)/sasA−(Km)/AMC541], the level of KaiC was restored (Fig. 5E). The additive effect of compound mutations on circadian gene expression suggests that labA and sasA are involved in different output pathways.

Table 1.

Phenotypic analysis of bioluminescence rhythm of labA−/sasA− double mutants

Maximum intensity and period length of the bioluminescence rhythms of the wild-type strain (AMC541), labA mutant [labA−(Ω)/AMC541], sasA mutant [sasA−(Km)/AMC541], and labA/sasA double-mutant [labA−(Ω)/sasA−(Km)/AMC541] cells determined from their second peaks under LL conditions. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM from five independent experiments.

It should be noted that the labA mutation also suppressed the short-period phenotype of the sasA mutant (Fig. 5C; Table 1). In the sasA mutant, phosphorylated KaiC was dominant at all the time points tested, as previously reported (Fig. 5E; Takai et al. 2006), whereas the circadian KaiC phosphorylation cycle was restored in the labA/sasA double mutant (Fig. 5E), probably due to restored kaiBC expression (Fig. 5C; Table 1). This restored KaiC phosphorylation cycle likely contributed to the suppression of the short-period phenotype of the sasA mutant.

We also examined the bioluminescence of labA/rpaA double mutants [labA−(Ω)/rpaA−(Km)/AMC541]. We found that the phenotype of the labA/rpaA double mutant was similar to that of the rpaA single mutant [rpaA−(Km)/AMC541], indicating that rpaA was epistatic to labA (Fig. 5D). These data are consistent with our earlier finding that the labA mutation could not suppress the rpaA overexpression phenotype (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that labA and rpaA function in the same transcriptional regulation pathway.

Suppression of slow-growth phenotype of the sasA mutant by labA mutation

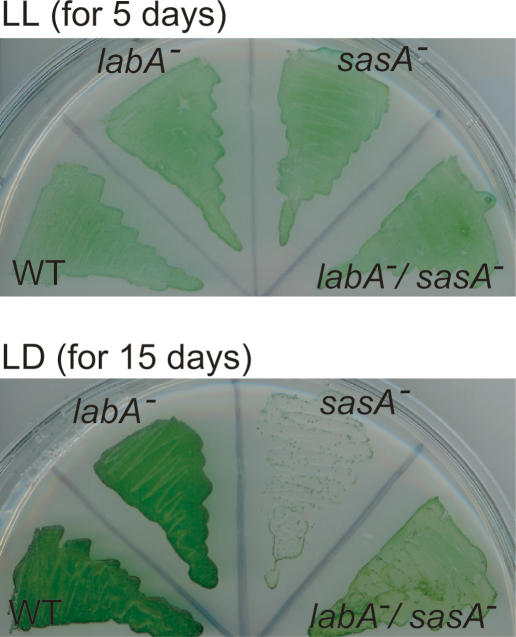

The sasA mutation causes a slow-growth phenotype under LD conditions (Iwasaki et al. 2000). We examined the effect of labA mutation on the slow-growth phenotype of the sasA mutant. On agar plates, the sasA mutant and the labA/sasA double mutant grew well under LL conditions (Fig. 6; Iwasaki et al. 2000). It should be noted that the slow-growth phenotype of labA mutants in this figure was obscured because the high-density cell cultures were plated and the growth was at saturation level in the conditions. Under LD conditions, the sasA mutant [sasA−(Km)/AMC541] showed a slow-growth phenotype (Fig. 6; Iwasaki et al. 2000), whereas labA/sasA double-mutant cells grew slower than wild-type cells (data not shown) but much faster than sasA mutant cells (Fig. 6). These results indicate that the labA mutation partially suppresses the slow-growth phenotype of sasA mutants under LD conditions.

Figure 6.

The labA mutation suppressed the slow-growth phenotype of the sasA mutant under LD conditions. Cultures of wild-type (AMC541), labA mutant [labA−(Ω)/AMC541], sasA mutant [sasA−(Km)/AMC541], and labA/sasA double mutant [labA−(Ω)/sasA−(Km)/AMC541] were streaked onto BG-11M agar plates and incubated under LL or LD cycle conditions at 30°C for 5 d (for LL) or 15 d (for LD). Note that the slow-growth phenotype of the labA mutant was obscured in these experiments because the growth was at saturation level.

Discussion

In this study, we have identified labA as a novel cyanobacterial gene that modulates circadian gene expression. Disruption of labA increased the trough levels of circadian gene expression, resulting in a low-amplitude phenotype (Figs. 1A, 3A–C, 5A–D; Supplementary Fig. S2). In addition, overexpression of labA significantly reduced circadian gene expression (Fig. 4). Thus, we conclude that labA acts as an inhibitor of circadian gene expression. Moreover, mutations in labA abolished transcriptional repression by overexpression of KaiC (Fig. 1A), suggesting that negative feedback regulation of KaiC is mediated by LabA. Overexpression of a mutant version of KaiC that cannot be phosphorylated fails to repress kaiBC promoter activity (Nishiwaki et al. 2004), suggesting that phosphorylated KaiC is involved in feedback regulation. Therefore, LabA is likely to function downstream from phosphorylated KaiC as a negative output path of the Kai-based central oscillator.

The SasA–RpaA two-component system is also involved in the output pathway that causes global gene expression to reflect circadian oscillation (Takai et al. 2006). This phospho-relay can be modulated by the state of the Kai-based oscillator. Our epistasis analysis strongly suggested that labA and sasA are involved in different output pathways of the circadian clock, whereas labA and rpaA function in the same transcriptional regulation pathway (Fig. 5). The labA mutation did not substantially interfere with transcriptional repression produced by rpaA overexpression (Fig. 5B), suggesting that rpaA functions downstream from labA. The inhibitory role of labA in circadian gene expression suggests that LabA might function as a “brake” on RpaA, whereas SasA acts as an “accelerator” of RpaA (Takai et al. 2006). In other words, RpaA is likely to receive temporal information from the circadian clock through at least two pathways: the LabA-dependent negative pathway and the SasA-dependent positive pathway. Since the labA/sasA double mutant did show circadian gene expression (Fig. 5C), there are likely additional circadian pathways that regulate RpaA. Because LabA did not interact with any Kai proteins, SasA, or RpaA in our yeast two-hybrid assays (Y. Taniguchi, unpubl.), LabA may interact indirectly with these clock-related proteins through yet unknown binding partners in cyanobacterial cells. The molecular partner of LabA remains to be elucidated.

Physiological roles of LabA in the circadian clock system

Previous work suggested a model for the cyanobacterial circadian clock system in which the KaiC phosphorylation cycle is coupled to a transcriptional–translational feedback loop (Tomita et al. 2005). Thus, LabA is likely to affect the entire circadian clock system through feedback regulation of KaiC (Fig. 1A).

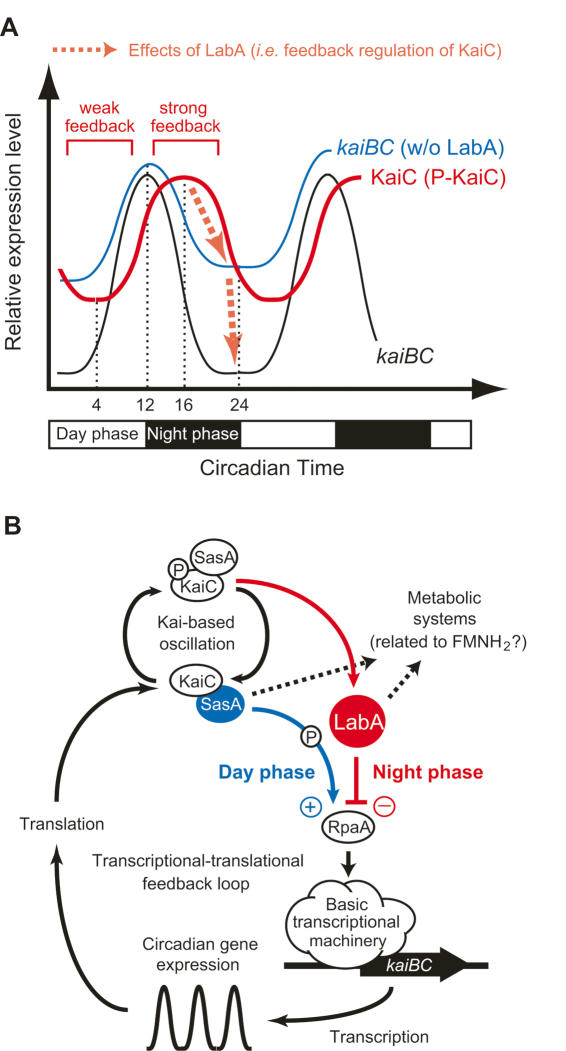

What are the physiological roles of LabA in this system? Our data show that LabA increases the peak/trough ratio of circadian gene expression via transcriptional repression. Earlier work suggested that the SasA–RpaA pathway is likely to be activated mainly in the subjective-day phase (Takai et al. 2006). Because the peak of SasA–RpaA phosphorylation in vitro occurs 4–8 h prior to that of phosphorylated KaiC, changes in its amount itself may not be the primary factor for the circadian regulation of this pathway (Takai et al. 2006). Consistent with this SasA–RpaA phosphorylation, kaiBC transcript fluctuates in vivo with a peak at circadian time (CT) 9–12 (subjective dusk) and a trough at CT 0 (subjective dawn) (Figs. 3C, 7A; Ishiura et al. 1998; Iwasaki et al. 2000; Imai et al. 2004; Takai et al. 2006). The fluctuation in KaiC protein and KaiC phosphorylation is shifted later in phase relative to that of kaiBC transcript. On the other hand, LabA is a key component for the feedback regulation responding to the amounts of (probably phosphorylated) KaiC (Fig. 1A).

Figure 7.

Models for LabA function in the transcriptional–translational feedback loop of the cyanobacterial circadian clock system. (A) Fluctuation of LabA activity relative to changes in the level of KaiC (probably phosphorylated). Profiles of kaiBC mRNA (black trace) and KaiC protein (red trace) abundance in cyanobacterial cells are depicted. In the labA mutant, kaiBC expression exhibited a low-amplitude rhythm due to lack of KaiC–LabA-dependent transcriptional repression during the subjective night phase (blue trace). (B) A possible model for LabA functions in the cyanobacterial circadian clock system. Details are described in the text.

Thus, we propose that transcriptional inhibition caused by LabA oscillates according to changes in the amount of phosphorylated KaiC. Total levels of KaiC and KaiC phosphorylation oscillate with a peak at CT 15–16 (subjective night) and a trough at CT 4 (subjective morning) (Figs. 3D, 7A; Xu et al. 2000; Iwasaki et al. 2002; Kitayama et al. 2003). Accordingly, KaiC-LabA is likely to strongly repress RpaA activity during subjective night, when KaiC is abundant, and to lower the trough level of transcriptional oscillation (Fig. 7A). During the subjective day, when KaiC levels are low, KaiC-LabA repressive activity is likely to be lower (Fig. 7A). The low-amplitude phenotype of labA mutants is consistent with this model (Fig. 7A). The LabA-dependent negative pathway, which appears to be regulated by the amount of clock components, presumably functions in harmony with the SasA-dependent positive pathway, which is regulated by the post-translational state of the Kai-based chemical oscillator. In our model, this system produces a phase difference between LabA and SasA activity that amplifies circadian oscillation (Fig. 7A). In addition, our data suggest that the level of LabA can determine at least in part the expression level of clock-controlled genes (Fig. 4C), presumably by modulating feedback regulation of KaiC. The balance between the positive activity of SasA and the negative activity of LabA is likely to be important for determining the amplitude of the circadian oscillation of clock-controlled genes.

LabA and the cellular metabolic/redox system

LabA also appears to be involved in the cellular redox/metabolic system, since labA mutants showed slower colony growth on agar plates (Fig. 3E). The extreme bright phenotype of labA mutant in the luxAB reporter strains implies excessive accumulation of FMNH2, an endogenous substrate for bacterial luciferase (Figs. 1A, 3A, 5A,B; Supplementary Fig. S2A). The circadian clock is able to affect cellular metabolic/redox states via transcriptional regulation, but since changes in kai gene expression did not substantially affect cellular growth rate on agar plates (Ishiura et al. 1998; Iwasaki et al. 2000; Nakahira et al. 2004), changes in clock gene expression in labA mutants may not explain the slow-growth phenotype in these cells. Through its regulation of both transcription and cellular metabolism, LabA may play a role in adaptation to light/dark alternation, since the labA mutation suppressed the slow-growth phenotype of the sasA mutant under LD conditions (Fig. 6). LabA and SasA might cooperatively modulate the cellular redox/metabolic system to adapt the daily light/dark alternation.

A model for cyanobacterial circadian gene expression system

We propose a model for LabA function in the cyanobacterial circadian clock system (Fig. 7B). First, Kai proteins generate the basic timing loop by regulating Kai-based chemical oscillation (Nakajima et al. 2005). Following its interaction with KaiC (Iwasaki et al. 2000), SasA is autophosphorylated and activates the putative transcription factor RpaA (Takai et al. 2006). It is presumed that RpaA controls circadian gene expression globally through the basic transcriptional machinery (Takai et al. 2006). The SasA–RpaA pathway appears to be activated by Kai proteins mainly during the subjective day phase (Takai et al. 2006), and the rhythmic activation of RpaA through KaiC–SasA generates the minimal transcriptional rhythm. Concurrently, KaiC represses RpaA function through the LabA-dependent pathway, mainly during the subjective night phase. LabA and SasA also cooperatively modulate the cellular redox/metabolic system. This KaiC–LabA–RpaA pathway model is largely based on our genetic analysis, and the molecular mechanism of this signal transduction pathway remains to be solved.

It is interesting to note that the key transcriptional factors crucial for circadian rhythm are likely to be regulated both positively and negatively by the circadian clock in other organisms. For instance, in Neurospora, the activity of the key circadian transcriptional activator White Collar Complex (WCC) is suppressed by the clock protein FRQ in the nucleus during morning/midday phase, whereas WCC accumulation is supported by cytosolic FRQ during evening phase (Brunner and Schafmeier 2006; Schafmeier et al. 2006). In mammals, CLOCK/BMAL1 heterodimers cooperate with coactivators such as p300/CREB-binding protein to activate transcription (Etchegaray et al. 2003), and with CRYPTOCHROME to repress transcription (Kondratov et al. 2006). These regulatory functions likely converge on the C terminus of BMAL1 to produce the appropriate balance of transcriptional activation and suppression (Kiyohara et al. 2006). Thus, the basic framework of transcriptional control by the circadian clock may be conserved and may contribute to the robustness of circadian clock systems.

LabA and the DUF88/COG1432 domain family

At present, no known domain/motif has been found in LabA. According to the Conserved Domain Database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Marchler-Bauer et al. 2003), the entire coding sequence of LabA belongs to the uncharacterized DUF88/COG1432 domain family (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Although many genes belonging to this family have been found in the genome of various prokaryotic species, their function and biochemical properties are unknown. To our knowledge, this is the first study that describes the functional characterization of a member of this family. Interestingly, a BLAST search (Altschul et al. 1990) revealed that a protein encoded by a putative ORF, MCA1614 of Methylococcus capsulatus, possesses a DUF88/COG1432 domain at the N-terminal region and a putative DNA/RNA-binding domain at the C-terminal region (Supplementary Fig. S1B). This implies that the DUF88/COG1432 domain has regulatory role(s) for protein functions. Biochemical characterization of LabA will be crucial for elucidating the mechanism by which LabA functions in the cyanobacterial circadian clock system.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and media

Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 was used as the background strain for the cyanobacterial reporter strains in this study. The NUC42 (PkaiBC∷luxAB) (Nishimura et al. 2002), AMC149 (PpsbAI∷luxAB) (Kondo et al. 1993), and PkaiRE (PkaiBC∷PxhRE) (Kitayama et al. 2004) reporter strains were constructed in previous studies. The firefly luciferase reporter strain, AMC541 [PkaiBC∷luc reporter inserted into NSII (CmR)], was a kind gift from Dr. S.S. Golden (Texas A&M University, College Station, TX) (Ditty et al. 2003). The PkaiBC∷luxAB reporter strain (NUC42) carrying the Ptrc∷kaiC transgene (OX-kaiC/NUC42) was described previously (Iwasaki et al. 2002). The PkaiBC∷luxAB reporter strain (NUC42) carrying the Ptrc∷sasA transgene (OX-sasA/NUC42) was provided by H. Iwasaki (Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan) (Iwasaki et al. 2000). The other cyanobacterial strains described were constructed in this study. Generation of the PkaiBC∷luxAB reporter strain carrying the Ptrc∷rpaA transgene (OX-rpaA/NUC42) is described in the Supplemental Material.

Cyanobacterial cells were grown in modified BG-11 medium (BG-11M) (Bustos and Golden 1991) or on BG-11M plates containing 1.5% Bacto Agar (Difco) at 30°C under continuous illumination (LL) of 40 μE m−2 sec−1 from white fluorescent lamps. Transformation of Synechococcus was described previously (Porter 1988; Kutsuna et al. 1998). For construction and propagation of plasmids, the Escherichia coli strains DH5α or TOP10 (Invitrogen) were used. E. coli cells were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar plate containing appropriate antibiotics.

Screening using transposon mutagenesis

To permit screening for a transposon carrying the kanamycin-resistance gene, the Kmr gene of OX-kaiC/NUC42 was disrupted by an Ω cassette. A plasmid carrying the Kmr gene (pACYC177) was digested with HindIII and PstI, and the Ω cassette was inserted. OX-kaiC/NUC42 was transformed with the resulting plasmid, and eight spectinomycin-resistant clones were selected. Among them, a kanamycin-sensitive clone [OX-kaiC(Ω)/NUC42] was used for further experiments. Sau3AI-digested genomic DNA from Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 was subcloned into the BamHI site of pBR322-inv-omega (the average insert size was ∼6.5 kb). This genomic library was mutagenized with the EZ∷TN <KAN-2> Insertion Kit (Epicentre) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. OX-kaiC(Ω)/NUC42 cells (2.5 OD730) were transformed with 0.5 μg of the mutagenized genomic library, and plated onto 20 BG-11M agar plates containing 5 μg/mL kanamycin. The bioluminescence rhythm of kanamycin-resistant clones (∼20,000 colonies) was monitored by a CCD camera apparatus (Kondo et al. 1994) in the presence of 1 mM IPTG. Among these, we picked 29 luminous colonies and confirmed their phenotypes again (IPTG was added at the third day of the assay). Finally, 10 confirmed clones were selected for further analysis. Genomic DNA purified from the clones was digested with EcoRI and subcloned into pBluescript II. DH5α was transformed with the ligation mixture, and kanamycin-resistant clones were selected. Plasmid was prepared from them, and regions flanking the transposons were sequenced with KAN-2 FP-1 primer and KAN-2 RP-1 primer (included in the EZ∷TN <KAN-2> Insertion Kit). The sequence of labA has been deposited in the DDBJ/GenBank/EMBL databases (accession no. AB281186).

Disruption of labA

A fragment containing the labA ORF was amplified by PCR using two primers: 5′-GACAACCCAGTTGGTAATTGCG-3′ and 5′-GGGCAAAAGGCCAATCGGTGAC-3′. The PCR product was subcloned into pGEM-T (Promega), and a Kmr or Ω cassette was inserted into the HpaI site of the labA gene to construct pDlabA(Kmr) or pDlabA(Ω), respectively (Fig. 1B). AMC149, NUC42, AMC541, PkaiRE, OX-kaiC(Ω)/NUC42, OX-sasA/NUC42, and OX-rpaA/NUC42 were transformed with pDlabA(Kmr) or pDlabA(Ω), and the transformants were selected in 25 μg/mL kanamycin or 40 μg/mL spectinomycin, respectively. The cells were checked by PCR to confirm labA disruption (data not shown). We monitored the bioluminescence rhythm of the cells essentially as described previously (Iwasaki et al. 1999). For entrainment of the circadian rhythm, cells were exposed to two LD cycles. For insect luciferase reporter strains, luciferin instead of n-decanal was added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM immediately before the assay. Addition of IPTG (for Figs. 1A, 5A,B) was performed as described previously (Ishiura et al. 1998).

Disruption of sasA and rpaA

pDsasA, a construct to disrupt the sasA gene, and an inactivation cassette to disrupt the rpaA gene were described previously (Iwasaki et al. 2000; Takai et al. 2006). AMC541 and labA−(Ω)/AMC541 were transformed with either construct, and mutants were selected in 25 μg/mL kanamycin. The bioluminescence assay was performed as described above.

Assaying the growth phenotype

For Figure 3E, cells were cultured in BG-11M medium under LL conditions (40 μE m−2 sec−1) with shaking for 6 d. The cultures were diluted with BG-11M medium, and 10 μL of each culture were spotted onto a BG-11M agar plate. After growing under the LL conditions at 30°C for 6 d, colonies were photographed. For Figure 6, the cyanobacterial liquid cultures grown under the LL conditions for several days were diluted to OD730 = 0.2, and aliquots (10 μL) were streaked onto BG-11M agar plates and incubated at 30°C under LL or LD conditions for 5 d or 15 d, respectively.

Overexpression of labA

To construct an IPTG-inducible labA vector, we performed PCR using two primers: 5′-CAAGACTCCATGGCATTTCGC CCTAGTCG-3′ (the NcoI site is underlined) and 5′-GTT GATGGGATCCAGGCTCATGCCGGAGC-3′ (the BamHI site is underlined). The PCR product was inserted into the NcoI–BamHI site of p322Ptrc (Kutsuna et al. 1998) to obtain p322Ptrc∷labA. p322Ptrc∷labA was digested with BglII, and the shorter fragment carrying lacIq-Ptrc∷labA was subcloned into the BamHI site of the pTS2KC targeting vector (Kutsuna et al. 1998) to obtain pOX-labA. NUC42 and AMC149 were transformed with pOX-labA, and kanamycin-resistant clones were obtained (the resulting strains were OX-labA/NUC42 and OX-labA/AMC149, respectively). For the complementation experiment in Supplementary Figure S3, labA-disrupted NUC42 [NUC42 transformed with pDlabA(Ω)] was transformed with pOX-labA. The bioluminescence assay and the addition of IPTG were performed as described previously (Ishiura et al. 1998). IPTG-dependent overexpression of labA was confirmed by Northern blotting (data not shown).

Northern and Western blotting analyses

Cells were precultured in BG-11M medium with aeration for four LD cycles and then transferred to a continuous culture system to maintain an OD730 of 0.2. The culture was additionally exposed to a 12-h dark pulse, and then returned to LL (40 μE m−2 sec−1 at 30°C with aeration). For labA overexpression, NUC42 and OX-labA/NUC42 were cultured with or without 1 mM IPTG in a continuous culture system as described above. Sampling was performed under the LL conditions every 3 or 6 h, and harvested cells were immediately frozen at −80°C. RNA preparation and Northern blotting analysis were performed as described previously (Ishiura et al. 1998; Kutsuna et al. 1998). Five micrograms of total RNA were loaded per lane. Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probes were prepared using the DIG DNA Labeling Mix (Roche). To prepare a probe for labA, two primers—5′-CAAGACTCCATGGCATTTCGCCCTAGT CG-3′ and 5′-GTTGATGGGATCCAGGCTCATGCCGGAG C-3′—were used. For the luxAB probe, 5′-GGGGACTGCT TTTTTGTACAAACTTGATGAAATTTGGAAACTTCCTTCT CAC-3′ and 5′-GGGGACAACTTTGTATAGAAAAGTTGT TACGAGTGGTATTTGACGATG-3′ were used. Preparation of kaiBC probe was described previously (Ishiura et al. 1998). Western blotting analysis (2 μg of total protein per lane) was performed as described previously (Nishiwaki et al. 2004). All experiments were performed two or three times.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Kondo laboratorty, especially Dr. Y. Nakahira for the mutagenized genomic library, Dr. H. Iwasaki for sasA-related materials and technical instructions, Dr. J. Tomita and Dr. M. Nakajima for technical instructions, Y. Murayama for Northern blotting, H. Kondo and T. Nishikawa for technical support, and Dr. M. Mutsuda and Dr. K. Yagita for valuable comments on this work. We also thank Dr. S.S. Golden (Texas A&M University) for providing AMC541. This research was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (15GS0308 to T.K. and T.O.), and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (17370088 to T.O.). Analysis of DNA sequences was conducted in conjunction with the Life Research Support Center at Akita Prefectural University.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1488107

References

- Altschul S.F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J., Lipman D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner M., Schafmeier T., Schafmeier T. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of the circadian clock of cyanobacteria and Neurospora. Genes & Dev. 2006;20:1061–1074. doi: 10.1101/gad.1410406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustos S.A., Golden S.S., Golden S.S. Expression of the psbDII gene in Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942 requires sequences downstream of the transcription start site. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:7525–7533. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.23.7525-7533.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditty J.L., Williams S.B., Golden S.S., Williams S.B., Golden S.S., Golden S.S. A cyanobacterial circadian timing mechanism. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2003;37:513–543. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.142716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etchegaray J.P., Lee C., Wade P.A., Reppert S.M., Lee C., Wade P.A., Reppert S.M., Wade P.A., Reppert S.M., Reppert S.M. Rhythmic histone acetylation underlies transcription in the mammalian circadian clock. Nature. 2003;421:177–182. doi: 10.1038/nature01314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K., Nishiwaki T., Kondo T., Iwasaki H., Nishiwaki T., Kondo T., Iwasaki H., Kondo T., Iwasaki H., Iwasaki H. Circadian rhythms in the synthesis and degradation of a master clock protein KaiC in cyanobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:36534–36539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405861200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiura M., Kutsuna K., Aoki S., Iwasaki H., Andersson C.R., Tanabe A., Golden S.S., Johnson C.H., Kondo T., Kutsuna K., Aoki S., Iwasaki H., Andersson C.R., Tanabe A., Golden S.S., Johnson C.H., Kondo T., Aoki S., Iwasaki H., Andersson C.R., Tanabe A., Golden S.S., Johnson C.H., Kondo T., Iwasaki H., Andersson C.R., Tanabe A., Golden S.S., Johnson C.H., Kondo T., Andersson C.R., Tanabe A., Golden S.S., Johnson C.H., Kondo T., Tanabe A., Golden S.S., Johnson C.H., Kondo T., Golden S.S., Johnson C.H., Kondo T., Johnson C.H., Kondo T., Kondo T. Expression of a gene cluster kaiABC as a circadian feedback process in cyanobacteria. Science. 1998;281:1519–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki H., Taniguchi Y., Ishiura M., Kondo T., Taniguchi Y., Ishiura M., Kondo T., Ishiura M., Kondo T., Kondo T. Physical interactions among circadian clock proteins KaiA, KaiB and KaiC in cyanobacteria. EMBO J. 1999;18:1137–1145. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki H., Williams S.B., Kitayama Y., Ishiura M., Golden S.S., Kondo T., Williams S.B., Kitayama Y., Ishiura M., Golden S.S., Kondo T., Kitayama Y., Ishiura M., Golden S.S., Kondo T., Ishiura M., Golden S.S., Kondo T., Golden S.S., Kondo T., Kondo T. A KaiC-interacting sensory histidine kinase, SasA, necessary to sustain robust circadian oscillation in cyanobacteria. Cell. 2000;101:223–233. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80832-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki H., Nishiwaki T., Kitayama Y., Nakajima M., Kondo T., Nishiwaki T., Kitayama Y., Nakajima M., Kondo T., Kitayama Y., Nakajima M., Kondo T., Nakajima M., Kondo T., Kondo T. KaiA-stimulated KaiC phosphorylation in circadian timing loops in cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002;99:15788–15793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222467299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama Y., Iwasaki H., Nishiwaki T., Kondo T., Iwasaki H., Nishiwaki T., Kondo T., Nishiwaki T., Kondo T., Kondo T. KaiB functions as an attenuator of KaiC phosphorylation in the cyanobacterial clock system. EMBO J. 2003;22:2127–2134. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama Y., Kondo T., Nakahira Y., Nishimura H., Ohmiya Y., Oyama T., Kondo T., Nakahira Y., Nishimura H., Ohmiya Y., Oyama T., Nakahira Y., Nishimura H., Ohmiya Y., Oyama T., Nishimura H., Ohmiya Y., Oyama T., Ohmiya Y., Oyama T., Oyama T. An in vivo dual-reporter system of cyanobacteria using two railroad-worm luciferases with different color emissions. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;45:109–113. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyohara Y.B., Tagao S., Tamanini F., Morita A., Sugisawa Y., Yasuda M., Yamanaka I., Ueda H.R., van der Horst G.T., Kondo T., Tagao S., Tamanini F., Morita A., Sugisawa Y., Yasuda M., Yamanaka I., Ueda H.R., van der Horst G.T., Kondo T., Tamanini F., Morita A., Sugisawa Y., Yasuda M., Yamanaka I., Ueda H.R., van der Horst G.T., Kondo T., Morita A., Sugisawa Y., Yasuda M., Yamanaka I., Ueda H.R., van der Horst G.T., Kondo T., Sugisawa Y., Yasuda M., Yamanaka I., Ueda H.R., van der Horst G.T., Kondo T., Yasuda M., Yamanaka I., Ueda H.R., van der Horst G.T., Kondo T., Yamanaka I., Ueda H.R., van der Horst G.T., Kondo T., Ueda H.R., van der Horst G.T., Kondo T., van der Horst G.T., Kondo T., Kondo T., et al. The BMAL1 C terminus regulates the circadian transcription feedback loop. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103:10074–10079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601416103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T., Strayer C.A., Kulkarni R.D., Taylor W., Ishiura M., Golden S.S., Johnson C.H., Strayer C.A., Kulkarni R.D., Taylor W., Ishiura M., Golden S.S., Johnson C.H., Kulkarni R.D., Taylor W., Ishiura M., Golden S.S., Johnson C.H., Taylor W., Ishiura M., Golden S.S., Johnson C.H., Ishiura M., Golden S.S., Johnson C.H., Golden S.S., Johnson C.H., Johnson C.H. Circadian rhythms in prokaryotes: Luciferase as a reporter of circadian gene expression in cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1993;90:5672–5676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T., Tsinoremas N.F., Golden S.S., Johnson C.H., Kutsuna S., Ishiura M., Tsinoremas N.F., Golden S.S., Johnson C.H., Kutsuna S., Ishiura M., Golden S.S., Johnson C.H., Kutsuna S., Ishiura M., Johnson C.H., Kutsuna S., Ishiura M., Kutsuna S., Ishiura M., Ishiura M. Circadian clock mutants of cyanobacteria. Science. 1994;266:1233–1236. doi: 10.1126/science.7973706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondratov R.V., Shamanna R.K., Kondratova A.A., Gorbacheva V.Y., Antoch M.P., Shamanna R.K., Kondratova A.A., Gorbacheva V.Y., Antoch M.P., Kondratova A.A., Gorbacheva V.Y., Antoch M.P., Gorbacheva V.Y., Antoch M.P., Antoch M.P. Dual role of the CLOCK/BMAL1 circadian complex in transcriptional regulation. FASEB J. 2006;20:530–532. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5321fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutsuna S., Kondo T., Aoki S., Ishiura M., Kondo T., Aoki S., Ishiura M., Aoki S., Ishiura M., Ishiura M. A period-extender gene, pex, that extends the period of the circadian clock in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:2167–2174. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.2167-2174.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Tsinoremas N.F., Johnson C.H., Lebedeva N.V., Golden S.S., Ishiura M., Kondo T., Tsinoremas N.F., Johnson C.H., Lebedeva N.V., Golden S.S., Ishiura M., Kondo T., Johnson C.H., Lebedeva N.V., Golden S.S., Ishiura M., Kondo T., Lebedeva N.V., Golden S.S., Ishiura M., Kondo T., Golden S.S., Ishiura M., Kondo T., Ishiura M., Kondo T., Kondo T. Circadian orchestration of gene expression in cyanobacteria. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:1469–1478. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.12.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A., Anderson J.B., DeWeese-Scott C., Fedorova N.D., Geer L.Y., He S., Hurwitz D.I., Jackson J.D., Jacobs A.R., Lanczycki C.J., Anderson J.B., DeWeese-Scott C., Fedorova N.D., Geer L.Y., He S., Hurwitz D.I., Jackson J.D., Jacobs A.R., Lanczycki C.J., DeWeese-Scott C., Fedorova N.D., Geer L.Y., He S., Hurwitz D.I., Jackson J.D., Jacobs A.R., Lanczycki C.J., Fedorova N.D., Geer L.Y., He S., Hurwitz D.I., Jackson J.D., Jacobs A.R., Lanczycki C.J., Geer L.Y., He S., Hurwitz D.I., Jackson J.D., Jacobs A.R., Lanczycki C.J., He S., Hurwitz D.I., Jackson J.D., Jacobs A.R., Lanczycki C.J., Hurwitz D.I., Jackson J.D., Jacobs A.R., Lanczycki C.J., Jackson J.D., Jacobs A.R., Lanczycki C.J., Jacobs A.R., Lanczycki C.J., Lanczycki C.J., et al. CDD: A curated Entrez database of conserved domain alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:383–387. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min H., Golden S.S., Golden S.S. A new circadian class 2 gene, opcA, whose product is important for reductant production at night in Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:6214–6221. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.21.6214-6221.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahira Y., Katayama M., Miyashita H., Kutsuna S., Iwasaki H., Oyama T., Kondo T., Katayama M., Miyashita H., Kutsuna S., Iwasaki H., Oyama T., Kondo T., Miyashita H., Kutsuna S., Iwasaki H., Oyama T., Kondo T., Kutsuna S., Iwasaki H., Oyama T., Kondo T., Iwasaki H., Oyama T., Kondo T., Oyama T., Kondo T., Kondo T. Global gene repression by KaiC as a master process of prokaryotic circadian system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004;101:881–885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307411100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M., Imai K., Ito H., Nishiwaki T., Murayama Y., Iwasaki H., Oyama T., Kondo T., Imai K., Ito H., Nishiwaki T., Murayama Y., Iwasaki H., Oyama T., Kondo T., Ito H., Nishiwaki T., Murayama Y., Iwasaki H., Oyama T., Kondo T., Nishiwaki T., Murayama Y., Iwasaki H., Oyama T., Kondo T., Murayama Y., Iwasaki H., Oyama T., Kondo T., Iwasaki H., Oyama T., Kondo T., Oyama T., Kondo T., Kondo T. Reconstitution of circadian oscillation of cyanobacterial KaiC phosphorylation in vitro. Science. 2005;308:414–415. doi: 10.1126/science.1108451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura H., Nakahira Y., Imai K., Tsuruhara A., Kondo H., Hayashi H., Hirai M., Saito H., Kondo T., Nakahira Y., Imai K., Tsuruhara A., Kondo H., Hayashi H., Hirai M., Saito H., Kondo T., Imai K., Tsuruhara A., Kondo H., Hayashi H., Hirai M., Saito H., Kondo T., Tsuruhara A., Kondo H., Hayashi H., Hirai M., Saito H., Kondo T., Kondo H., Hayashi H., Hirai M., Saito H., Kondo T., Hayashi H., Hirai M., Saito H., Kondo T., Hirai M., Saito H., Kondo T., Saito H., Kondo T., Kondo T. Mutations in KaiA, a clock protein, extend the period of circadian rhythm in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. Microbiology. 2002;148:2903–2909. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-9-2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiwaki T., Iwasaki H., Ishiura M., Kondo T., Iwasaki H., Ishiura M., Kondo T., Ishiura M., Kondo T., Kondo T. Nucleotide binding and autophosphorylation of the clock protein KaiC as a circadian timing process of cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000;97:495–499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiwaki T., Satomi Y., Nakajima M., Lee C., Kiyohara R., Kageyama H., Kitayama Y., Temamoto M., Yamaguchi A., Hijikata A., Satomi Y., Nakajima M., Lee C., Kiyohara R., Kageyama H., Kitayama Y., Temamoto M., Yamaguchi A., Hijikata A., Nakajima M., Lee C., Kiyohara R., Kageyama H., Kitayama Y., Temamoto M., Yamaguchi A., Hijikata A., Lee C., Kiyohara R., Kageyama H., Kitayama Y., Temamoto M., Yamaguchi A., Hijikata A., Kiyohara R., Kageyama H., Kitayama Y., Temamoto M., Yamaguchi A., Hijikata A., Kageyama H., Kitayama Y., Temamoto M., Yamaguchi A., Hijikata A., Kitayama Y., Temamoto M., Yamaguchi A., Hijikata A., Temamoto M., Yamaguchi A., Hijikata A., Yamaguchi A., Hijikata A., Hijikata A., et al. Role of KaiC phosphorylation in the circadian clock system of Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004;101:13927–13932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403906101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter R.D. DNA transformation. Methods Enzymol. 1988;167:703–712. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)67081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafmeier T., Kaldi K., Diernfellner A., Mohr C., Brunner M., Kaldi K., Diernfellner A., Mohr C., Brunner M., Diernfellner A., Mohr C., Brunner M., Mohr C., Brunner M., Brunner M. Phosphorylation-dependent maturation of Neurospora circadian clock protein from a nuclear repressor toward a cytoplasmic activator. Genes & Dev. 2006;20:297–306. doi: 10.1101/gad.360906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R.M., Williams S.B., Williams S.B. Circadian rhythms in gene transcription imparted by chromosome compaction in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103:8564–8569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508696103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai N., Nakajima M., Oyama T., Kito R., Sugita C., Sugita M., Kondo T., Iwasaki H., Nakajima M., Oyama T., Kito R., Sugita C., Sugita M., Kondo T., Iwasaki H., Oyama T., Kito R., Sugita C., Sugita M., Kondo T., Iwasaki H., Kito R., Sugita C., Sugita M., Kondo T., Iwasaki H., Sugita C., Sugita M., Kondo T., Iwasaki H., Sugita M., Kondo T., Iwasaki H., Kondo T., Iwasaki H., Iwasaki H. A KaiC-associating SasA–RpaA two-component regulatory system as a major circadian timing mediator in cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103:12109–12114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602955103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi Y., Yamaguchi A., Hijikata A., Iwasaki H., Kamagata K., Ishiura M., Go M., Kondo T., Yamaguchi A., Hijikata A., Iwasaki H., Kamagata K., Ishiura M., Go M., Kondo T., Hijikata A., Iwasaki H., Kamagata K., Ishiura M., Go M., Kondo T., Iwasaki H., Kamagata K., Ishiura M., Go M., Kondo T., Kamagata K., Ishiura M., Go M., Kondo T., Ishiura M., Go M., Kondo T., Go M., Kondo T., Kondo T. Two KaiA-binding domains of cyanobacterial circadian clock protein KaiC. FEBS Lett. 2001;496:86–90. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita J., Nakajima M., Kondo T., Iwasaki H., Nakajima M., Kondo T., Iwasaki H., Kondo T., Iwasaki H., Iwasaki H. No transcription–translation feedback in circadian rhythm of KaiC phosphorylation. Science. 2005;307:251–254. doi: 10.1126/science.1102540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzumaki T., Fujita M., Nakatsu T., Hayashi F., Shibata H., Itoh N., Kato H., Ishiura M., Fujita M., Nakatsu T., Hayashi F., Shibata H., Itoh N., Kato H., Ishiura M., Nakatsu T., Hayashi F., Shibata H., Itoh N., Kato H., Ishiura M., Hayashi F., Shibata H., Itoh N., Kato H., Ishiura M., Shibata H., Itoh N., Kato H., Ishiura M., Itoh N., Kato H., Ishiura M., Kato H., Ishiura M., Ishiura M. Crystal structure of the C-terminal clock-oscillator domain of the cyanobacterial KaiA protein. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:623–631. doi: 10.1038/nsmb781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S.B., Vakonakis I., Golden S.S., LiWang A.C., Vakonakis I., Golden S.S., LiWang A.C., Golden S.S., LiWang A.C., LiWang A.C. Structure and function from the circadian clock protein KaiA of Synechococcus elongatus: A potential clock input mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002;99:15357–15362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232517099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Mori T., Johnson C.H., Mori T., Johnson C.H., Johnson C.H. Circadian clock-protein expression in cyanobacteria: Rhythms and phase setting. EMBO J. 2000;19:3349–3357. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Mori T., Johnson C.H., Mori T., Johnson C.H., Johnson C.H. Cyanobacterial circadian clockwork: Roles of KaiA, KaiB and the kaiBC promoter in regulating KaiC. EMBO J. 2003;22:2117–2126. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]