Abstract

We have investigated the role of ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels in an experimental model of a delayed phase of vascular hyporeactivity induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in rats.

After 24 h, from LPS treatment, in anaesthetized rats the bolus injection of phenylephrine (PE) produced an increase in mean arterial pressure (MAP) significantly (P<0.05) reduced in LPS-treated rats compared to the vehicle-treated rats. This reduction was prevented by pre-treatment of rats with glibenclamide (GLB), a selective inhibitor of KATP channels.

GLB administration did not affect the MAP in vehicle-treated rats but produced an increase of MAP in rats treated with LPS.

Cromakalim (CRK), a selective KATP channel opener, produced a reduction of MAP that was significantly (P<0.05) higher in LPS- than in vehicle-treated rats. In contrast, the hypotension induced by glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) in LPS-treated rats was not distinguishable from that produced in vehicle-treated rats.

Experiments in vitro were conducted on aorta rings collected from rats treated with vehicle or LPS 24 h before sacrifice. The concentration-dependent curve to PE was statistically (P<0.005) reduced in aorta rings collected from LPS- compared to vehicle-treated rats. This difference was totally abolished by tetraethylammonium (TEA), a non-selective inhibitor of K+ channels.

CRK produced a relaxation of PE precontracted aorta rings higher in rings from LPS- than in vehicle-treated rats. GLB inhibited CRK-induced relaxation in both tissues, abolishing the observed differences.

In conclusion, our results indicate an involvement of KATP channels to the hyporesponsiveness of vascular tissue after 24 h from a single injection of LPS in rats. We can presume an increase in the activity of KATP channels on vascular smooth muscle cells but we cannot exclude an increase of KATP channel number probably due to the gene expression activation.

Keywords: KATP channels, cromakalim, glibenclamide, arterial blood pressure, tetraethylammonium, L-NAME, LPS

Introduction

Loss of vascular responsiveness to vasoconstrictor agents develops following a bacterial LPS-injection in animal models and may be an important factor contributing to eventual circulatory collapse. Vascular hyporeactivity can be observed both in vivo (Schaller et al., 1985) and ex vivo in vessels isolated from LPS-treated animals (Wakabayashi et al., 1987). A decrease in responses to a variety of contracting agents has been shown, including those which do not act via a receptorial pathway (Parratt, 1989).

LPS activates many cell types and when it is administered to the whole animal a variety of factors are released, which may be the cause of vascular hyporeactivity. A relevant role has been ascribed to tumour necrosis factor (Bentler, 1990), platelet activating factor (Etienne et al., 1986), prostacyclin (Halushka et al., 1985), complement-derived C5a anaphylatoxin (Smedegard et al., 1989) and nitric oxide (NO; Thiemermann & Vane, 1990; Kosaka et al., 1992). But the inhibitors of these agents are abroad in the resolution of septic shock that remains a frequently fatal disorder (Parrillo et al., 1990). The hypotension and the vascular hyporeactivity, observed in LPS-induced shock, has biphasic behaviour. An early phase (0–90 min) in which a direct release of vasorelaxant mediators is observed and a delayed phase (1.5–24 h) where the increase of vasorelaxant mediator release occurs on account of inducible enzyme isoform expression, like group II extracellular phospholipase A2 (Nakano & Arita, 1990), cyclo-oxygenase 2 and the inducible nitric oxide synthase (Swierkosz et al., 1995).

Many works report about mediators and their related enzymes that are involved in the LPS-induced vascular hyporeactivity, but few works are addressed to the observation of any change in membrane receptors or channels, which could be involved. The identification of KATP channels on vascular smooth muscle as regulators of membrane potential, contribute to the comprehension of vascular tone regulation (Standen et al., 1989). The opening of KATP channels in the cell membrane of smooth muscle cells of the microcirculation arterioles (resistance vessels) increases K+ efflux, which cause membrane potential hyperpolarization (see Nelson & Quayle, 1995). Recently it has been shown, that GLB, a specific inhibitor of KATP channels, administered in the early phase of endotoxemia, 30 min in the dog (Landry & Oliver, 1992) and 60 min in the rat (Wu et al., 1995) after LPS injection, caused vasoconstriction and restoration of blood pressure. Since in endotoxemia, induced by LPS, the vascular response is time-dependent, this study takes into account the probable involvement of KATP channels in the delayed phase (24 h) of LPS-induced hyporeactivity.

Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats (Charles River, Italy) were housed in an environment with controlled temperature (21–24°C) and lighting (12 : 12 h light-darkness cycle). Standard laboratory chow and drinking water were provided ad libitum. A period of 7 days was allowed for acclimatization of rats before any experimental manipulation was undertaken. At the time of the experiments, the body weight ranged from 200–300 g. All the experiments were conducted according to guidelines established by the U.B.C. Animal Care Committee.

Rats were divided in two groups in a random block design and treated 24 h before experiments with LPS (8×106 u kg−1) or vehicle (NaCl 0.9%, w v−1).

Measurement of haemodynamic changes in vivo

Tracheotomy was performed in rats under urethane anaesthesia (1 g kg−1 i.p.) and carotid artery, jugular vein and trachea were dissected. A polyethylene cannula (PE-50) was placed in the internal jugular vein and in the left carotid artery for administration of drugs and blood pressure monitoring respectively. The PE-50 catheter inserted into the left carotid artery was connected to a Bentley 800 Trantec (Basile, Comerio, Italy) for blood pressure monitoring. The line was filled with heparinized saline (5 units ml−1) to maintain patency. Blood pressure was recorded using the Thermal Arraycorder WR 7400 (Graphtec, Tokyo) recorder. The ECG and the heart rate (HR) were recorded by means of an electrocardiograph (Cardiette®, Elettronica Trentina, Trento, Italy). After 30 min of stabilization, drugs were administered via jugular vein.

PE (10, 30 and 100 μg kg−1 i.v.) was administered in bolus with an interval of 5 min in vehicle- or LPS-treated rats. GLB (40 mg kg−1 i.p.) was administered 1 h before PE injection.

CRK (150 μg kg−1 i.v.) or GTN (500 μg kg−1 i.v.) was administered in bolus in vehicle- or LPS-treated rats. GLB (40 mg kg−1 i.p.) or of NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester infusion (L-NAME; 3 μg kg−1 min−1 i.v.) were administered 60 and 30 min before CRK injection respectively. The dose of GLB was experimentally determined as the dose that produced a reduction of 50% of CRK-induced hypotension (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Reduction of MAP induced by cromakalim (150 μg kg−1 i.v.; CRK) or glyceryl trinitrate (500 μg kg−1 i.v.; GTN) in rats treated with vehicle or lipopolysaccharide (8×106 u kg−1 i.p.; LPS) 24 h before the experiment. Effect of glibenclamide (40 mg kg−1 i.p.; GLB) or L-NAME (3 μg kg−1 min−1) on CRK-induced reduction of MAP. Results are expressed as per cent of basal MAP and shown as mean±s.e.mean of 5–7 animals. *P<0.05 vs vehicle alone, **P<0.01 vs vehicle alone, ***P<0.001 vs vehicle alone, ΦP<0.05 vs LPS alone and ΦΦP<0.001 vs LPS alone.

Mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) was calculated according to the formula reported by Smith & Kampine (1984). Changes in MAP were expressed as per cent variation of basal value. The value of MAP just before drug administration was taken as basal value. One or two tailed Student's t-test was used for comparison of paired or unpaired data. The differences were recognized as statistically significant when P<0.05.

Organ bath experiments

After 24 h from LPS or vehicle treatment, rats were sacrificed by cervical dislocation after exposure to CO2 and their thoracic aorta were excised and carefully cleaned of connective tissue, cut in rings (2–3 mm) and the endothelium gently removed. The rings were then hooked in 2.5 ml water jacketed organ baths filled with thermostated (37°C) and gassed (95% O2 and 5% CO2) Krebs solution with the following composition (mM): NaCl, 115.3; KCl, 4.9; CaCl2, 1.46; MgSO4, 1.2; KH2PO4, 1.2; NaHCO3, 25.0 and glucose, 11.1. Rings were connected to isometric force transducers (model 7002, Basile, Comerio, Italy) and change in tension recorded continuously using a polygraph linearcorder (WR3310, Graphtec, Japan). Tissues were preloaded with 0.5 g and allowed equilibrating for at least 90 min, during this time Krebs solution was changed about each 15 min. After equilibration, tissues were either used for an ascending PE concentration-response study of contraction, in which cumulative additions of PE (1 nM–3 μM, in 0.5 log units) were added to tissue bath or for a descending CRK (from 10 nM–100 μM, in 0.5 log units) or GTN (1 nM–1 μM, in 0.5 log units) concentration-response study of relaxation on PE (1 μM) precontracted tissue.

For contracting study, the inhibitor GLB (30 μM) or L-NAME (100 μM) was added to the organ bath 15 min before starting PE concentration-response curve, whereas TEA (10 mM) was added 1 h before. For relaxing study, the inhibitor GLB (30 μM) or L-NAME was added to the organ bath on the stable tone induced by PE 1 μM 15 min before CRK adding.

For contracting responses results are expressed in dyne mg−1 of fresh tissue as mean±s.e.mean. For relaxing responses results are expressed in per cent of relaxation as mean±s.e.mean. All curves were compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and values of P<0.05 were taken as significant.

Drugs

All salts for Krebs solution were purchased from Carlo Erba (Milan, Italy). PE, GLB, TEA hydrochloride, L-NAME, lipopolysaccharide (from Escherichia coli, serotype 0127:B8), CRK, were purchased from Sigma (Milan, Italy). GTN (Venitrin®) was purchased from ASTRA Farmaceutici. For in vivo study CRK was suspended in polyethylenglycol (0.5 ml kg−1 of animal, i.v.) and GLB was dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide (0.5 ml kg−1 i.p.). For in vitro study either CRK or GLB were dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide and its maximum adding to the organ bath was of 1.5% (v v−1). All other drugs were dissolved in normal saline (NaCl 0.9% w v−1).

Results

In vivo experiment

After 24 h from LPS (8×106 u kg−1 i.p.) treatment, animals did not show any statistical (P>0.05, n=12) variation of MAP and HR (101±6 mmHg and 394±44 beats min−1 for vehicle treated and 99±5 mmHg and 409±32 beats min−1 for LPS treated rats). Bolus injection of PE (10, 30 and 100 μg kg−1 i.v.) produced an increase in MAP that resulted significantly (P<0.05; n=9) reduced in LPS-treated rats at doses of 30 and 100 μg kg−1 compared to the vehicle treated rats (Figure 1). This reduction in PE response in LPS-treated rats was completely abolished by pretreatment with GLB (40 mg kg−1 i.v.) which did not affect the response to PE in vehicle treated rats (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Changes in MAP induced by phenylephrine (10, 30 and 100 μg kg−1 i.v.; PE) in rats treated 24 h before with vehicle or lipopolysaccharide (8×106 u kg−1 i.p.; LPS) and effect of glibenclamide (40 mg kg−1 i.p.; GLB) administered 1 h before the contracting agent. Results are expressed as per cent of basal MAP and shown as mean±s.e.mean of 9–12 animals; *P<0.05 vs vehicle ΦP<0.05 vs LPS+GLB and ΦΦP<0.01 vs LPS+GLB.

GLB (40 mg kg−1 i.p.), by itself, when administered in vehicle-treated rats did not produce any variation of basal MAP. Variations of basal MAP (95±9 mmHg; n=6) were of 0.4±2.5, 0.3±4.6 and −2.2±3.4% at 15, 30 and 60 min respectively. In contrast, in LPS-treated rats the administration of GLB produced a statistically significant (P<0.05, n=7) increase in MAP of 6.9±0.8, 7.2±2.6 and 7.8±2.4% at 15, 30 and 60 min, respectively from a basal MAP value of 93±7 mmHg (Figure 2). No variation in HR between two groups was observed after GLB treatment (340±21 beats min−1 for vehicle- and 357±25 beats min−1 for LPS-treated rats).

Figure 2.

Effect of glibenclamide (40 mg kg−1 i.p.; GLB) on MAP in rats treated with either vehicle of lipopolysaccharide (8×106 u kg−1 i.p.; LPS) 24 h before the experiment. Results are expressed as per cent of basal MAP and shown as mean±s.e.mean of 6–7 animals; *P<0.05.

CRK administration (150 μg kg−1 i.v.) in LPS treated rats produced a reduction of MAP which was statistically (P<0.05; n=5) significantly deeper than in vehicle treated group (Figure 3). No variations in HR were observed after CRK administration (375±26 beats min−1 for vehicle- and 405±26 beats min−1 for LPS-treated rats). Pretreatment with GLB (40 mg kg−1 i.p.), 1 h before CRK administration, antagonized, with equal extends in both groups, the hypotensive action of the KATP channel opener, abolishing the observed differences betwen groups (Figure 3). Pretreatment with L-NAME (3 μg kg−1 min−1 i.v.) produced a further significant (P<0.05 vs LPS-treated rats and P<0.01 vs vehicle-treated rats) increase of CRK induced hypotension (Figure 3) in LPS, but not in vehicle-treated rats.

To verify if this increase in the hypotensive effect of CRK was a specific effect of KATP channel opener or related to an increased capability of vascular smooth cells to relax, we also tested GTN. The reduction of MAP induced by GTN (500 μg kg−1 i.v.; n=6) administration in LPS-treated rats (n=6) was similar to those produced in vehicle-treated rats (P>0.05; n=5; Figure 3).

In vitro experiments

Effect of KATP channel inhibitors on rat aorta hyporeactivity to PE

The contraction-related increase in vascular tone induced by PE (from 1 nM–3 μM) was significantly (P<0.001) reduced in aorta rings obtained from rats treated with LPS (n=6) 24 h before sacrifice, compared to rings obtained from vehicle-treated rats (n=4; Figure 4a). GLB addition (30 and 100 μM) to the organ bath produced a statistically significant (P<0.05 and P<0.001; n=3–4 respectively) inhibition of increase in vascular tone induced by PE of aorta rings dissected from both vehicle- and LPS-treated rats in a concentration dependent manner (Figure 4a). Since GLB impaired the contractility to PE in both tissues, we tested TEA, the non-selective inhibitor of K+ channels. TEA (10 mM) did not modify the concentration-response curve to PE of vehicle-treated rats (Figure 4b); but it reverted the hyporeactivity to PE in aorta rings from LPS treated rats.

Figure 4.

Effect of glibenclamide (30 and 100 μM; GLB; (a), tetraethylammonium (10 mM; TEA; (b) or NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (100 μM; L-NAME; (c) on concentration-response curve to phenylephrine (1 nM–3 μM; PE) of aorta rings collected from lipopolysaccharide (8×106 u kg−1 i.p.; LPS) or vehicle treated rats 24 h before experiment. Results are expressed as mean±s.e.mean of 12 aorta rings. Curves were compared by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and following results were obtained: (a) vehicle vs LPS P<0.001, vehicle vs vehicle+GLB 30 μM P<0.05, vehicle vs vehicle+GLB 100 μM P<0.001, LPS vs LPS+GLB 30 μM P<0.05, LPS vs LPS+GLB 100 μM P<0.001; (b) vehicle vs LPS P<0.001, vehicle vs vehicle+TEA P>0.05, LPS vs LPS+TEA P<0.001, vehicle vs LPS+TEA P>0.05; (c) vehicle vs LPS P<0.001, vehicle vs vehicle+L-NAME P=0.05, LPS vs LPS+L-NAME P<0.001, vehicle+L-NAME vs LPS+L-NAME P<0.01.

The addition of L-NAME (100 μM) to the organ bath, 15 min before PE concentration-response curve, produced an increase in the response of α1 adrenoceptors in both tissues (Figure 4c).

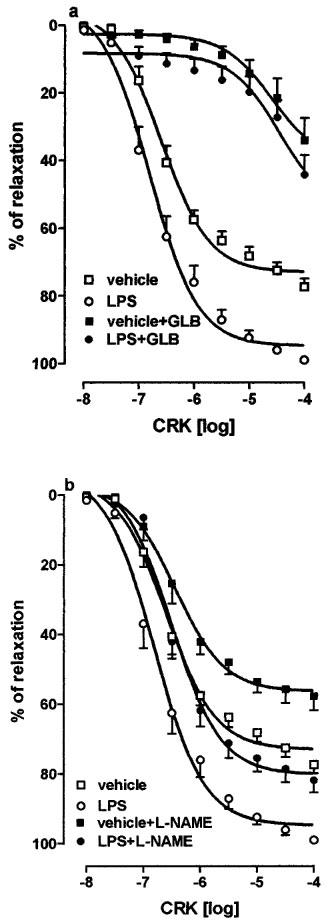

Effect of CRK on aorta rings

CRK (from 10 nM–100 μM), added to the organ bath on rat aorta rings precontracted with PE (1 μM), produced a relaxation in a cumulative concentration-dependent manner. This relaxation was statistically (P<0.001) higher in aorta rings collected from LPS- (n=6) than in vehicle-treated (n=5) rats (Figure 5). No differences at all, between two groups, were observed when the relaxation of aorta rings was induced with GTN (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Effect of glibenclamide (30 μM; GLB, (a) or NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (100 μM; L-NAME; (b) on cromakalim (10 nM–100 μM; CRK) induced vasorelaxation of phenylephrine (1 μM) precontracted aorta rings, collected from vehicle or lipopolysaccharide (8×106 u kg−1 i.p.; LPS) treated rats 24 h before experiment. Results are expressed as mean±s.e.mean of 12 aorta rings. Curves were compared by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and following results were obtained: (a) vehicle vs LPS P<0.001, vehicle vs vehicle+GLB P<0.001, LPS vs LPS+GLB P<0.001, vehicle+GLB vs LPS+GLB P>0.05; (b) vehicle vs LPS P<0.001, vehicle vs vehicle+L-NAME P=0.001, LPS vs LPS+L-NAME P<0.001, vehicle+L-NAME vs LPS+L-NAME P<0.001.

GLB (30 μM) added to the organ bath on PE-induced contraction did not modify the tone of the vessel (data not shown), but it inhibited (P<0.001) relaxation of vascular smooth muscle induced by CRK (Figure 5a) in both tissues, abolishing the differences between rings from vehicle- and LPS-treated rats (P>0.65, n=6).

The presence of NO synthase inhibitor, L-NAME (100 μM), into organ bath decreased PE-induced contraction, from 192.5±15.6 to 256.7±27.9 dyne mg−1 of tissue, in aorta rings from vehicle treated rats and, from 114.1±9.4 to 163.2±13.5 dyne mg−1 of tissue, in aorta rings from LPS treated rats. The presence of L-NAME in the organ bath reduced in equal extents the CRK-induced relaxation in both tissues (Figure 5b).

Discussion

KATP channels are present in almost all tissues as well as in vascular smooth muscle (Standen et al., 1989; Kovacs & Nelson, 1991; Nelson & Quayle, 1995). The change in potassium conductance of the smooth muscle cell membrane produces a relaxation of blood vessels. Several, chemically different, agents are K+ channel openers and they act as potent vasodilators. These events attribute a relevant role of KATP channels in the regulation of vascular tone and their action can be implicated in several pathological events (see Nelson & Quayle, 1995).

It has been shown that hypotension and fall in peripheral vascular resistance, which occur in the early phase of septic shock, are at least in great part due to activation of KATP channels in vascular smooth muscle, indeed, the administration of GLB, at maximum peak of LPS-induced hypotension in dogs (about 30 min; Landry & Oliver, 1992) or after 60 min from LPS injection in rats (Wu et al., 1995) was able to revert instantaneously the endotoxic shock. In this study we demonstrate that after 24 h from LPS treatment is still observed a vascular hyporeactivity that could be, in part, due to the involvement of KATP channels on vascular smooth muscle. Even though a significant reduction in MAP was not observed in rats after 24 h from LPS treatment, a significant reduction to the contracting agent PE was observed. This reduction in PE-induced contraction was abolished by pretreatment with GLB, a specific KATP channel antagonist (Beech et al., 1993). In addition, the administration in vivo of GLB in LPS-treated rats produced a significant increase in MAP, this effect was not detected in vehicle treated rats.

A further proof of the increase in KATP channel activity, in LPS treated rats, was due by the administration of CRK, a selective activator of KATP channels (Nelson & Quayle, 1995). The administration of CRK in anaesthetized LPS-treated rats produced a reduction of MAP significantly higher than in vehicle-treated rats. This difference can be ascribed only to the major activation of KATP channels but not to the reduced reactivity versus contracting agents in LPS-treated rats (Bigaud et al., 1990), since it was totally blocked by pretreatment with GLB. Furthermore, the difference in fall MAP was not observed using GTN, a donor of NO, which acts directly on terminal effector: the guanylate cyclase.

Since LPS treatment produces a myriad of mediators in vivo, which can activate and/or interfere with KATP channels, we performed in vitro experiments collecting aorta from ex vivo LPS-treated rats. Also in vitro, as well as in vivo, a hyporeactivity to PE of aorta rings from LPS-treated rat was observed. The hyporeactivity to PE was totally abolished by TEA administration, which did not modify the adrenergic α1-induced contraction in aorta rings from vehicle-treated rats. This drug, at used concentration, is able to inhibit either KCa and KATP channels (Nelson & Quayle, 1995), for this reason we cannot exclude also a participation of KCa channels to the observed vascular hyporeactivity 24 h after LPS treatment. Results obtained with GLB were excluded from computation since GLB by itself inhibited, in concentration-dependent manner, the contraction induced by PE in both tissues (Figure 4a). The mechanism by which GLB inhibited in vitro the contraction induced by α1 adrenergic agonist must be elucidated. Probably, the observed effect of GLB on aorta rings in vitro could mask the increase in tension to contracting agents induced by inhibition of KATP channels in aorta rings from LPS-treated rats. This could be the reason of KATP channel exclusion from endotoxic vascular hyporeactivity measured in vitro by some authors (Wu et al., 1995; Taguchi et al., 1996; Hall et al., 1996), although they operated at different observation time and experimental condition.

Also in vitro, CRK, in a concentration-dependent manner, showed a statistical significant increase of relaxation in aorta rings from ex vivo LPS- compared to vehicle-treated rats. This observed increase was abolished, as well as the relaxation, by adding GLB to the organ bath. In this case GLB was added on the stable state of PE-induced contraction without change of the tone (data not shown).

There is plentiful evidence that an enhanced formation of NO, principally by calcium independent inducible isoform of NO synthase, contributes to hypotension and hyporeactivity to endogenous and exogenous vasoconstrictor agents in septic shock (Thiemermann, 1994). Furthermore, it has been shown that NO, besides acting on its direct effector, can activate KATP channels inducing a hyperpolarization of membrane (Miyoshi et al., 1994; Murphy & Brayden, 1995). We can exclude NO participation because L-NAME treatment, in vitro, did not revert the hyporeactivity to PE and it reduced with equal extent the relaxation of rat aorta rings induced by CRK in both LPS- or vehicle-treated rats. Pretreatment with L-NAME in vivo did not increase MAP in LPS- compared to vehicle-treated rats. Furthermore, the hypotension induced by CRK in L-NAME pretreated rats was increased in LPS, but not in vehicle, treated rats. This increased potency to CRK observed in vivo, in presence of NO synthase inhibitor, may result in reduced KATP channels activation by endogenous NO, produced by endothelial constitutive NO synthase, and therefore there will be more channels available for KATP channel opener to interact with (McCulloch & Randall, 1996). However, an involvement of NO can also be excluded by the fact that the activity of inducible isoform of NO synthase, after a single injection of LPS, is maximal within approximately 6 h and returns to baseline within 24 h (Mitchell et al., 1993; Thiemermann, 1994).

We can also exclude, in LPS treated rats, an increase in capability of vascular smooth muscle to relax, since GTN, the direct vasodilator, did not produce a significant increase in hypotension compared to vehicle-treated rats.

These results, either in vivo or in vitro, indicate that the hyporeactivity, observed 24 h after LPS treatment in rats, could be due to the major activation of KATP channels, which convey in hyperpolarization of smooth muscle membrane, counteract the action of contracting agents on vascular tissue. In conclusion, our results show that there is still an involvement of KATP channels to the hyporesponsiveness of vascular tissue after 24 h from a single injection of LPS in rats. LPS is known to stimulate the synthesis and release of several cytokines, enzymes and biological mediators (Giroir, 1993; Thiemermann, 1994; Swierkosz et al., 1995) having hypotensive activity. The myriad of endocellular mediators released by LPS could explain the KATP channel hyperactivity observed in LPS-treated rats. However, we cannot exclude an increase of KATP channel number induced by gene expression activation.

Abbreviations

- CRK

cromakalim

- GLB

glibenclamide

- GTN

glyceryl trinitrate

- HR

heart rate

- K+

potassium

- KATP

ATP-sensitive potassium channels

- KCa

calcium-sensitive potassium channels

- L-NAME

NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- NO

nitric oxide

- PE

phenylephrine

- TEA

tetraethylammonium

References

- BEECH D.J., ZHANG H., NAKAO K., BOLTON T.B. K+ channel activation by nucleotide diphosphates and its inhibition by glibenclamide in vascular smooth muscle cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;110:573–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13849.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENTLER B.Cachetin/Tumor necrosis factor and lymphotoxin Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology Peptide Growth Factors and Their Receptor II 1990Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 39–70.ed. Sporn, M.B. & Roberts, A.B. pp [Google Scholar]

- BIGAUD M., JOULOU-SCHAEFFER G., PARRATT J.R., STOCLET J. Endotoxin-induced impairment of vascular smooth muscle contractions elicited by different mechanisms. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1990;190:185–192. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)94125-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ETIENNE A., HECQUET C., SOULARD C., TOUVAY F., CLOSTRE F., BRAQUET P. The relative role of PAF-acether and eicosanoids in septic shock. Pharmacol. Res. Commun. 1986;18 Suppl:71–79. doi: 10.1016/0031-6989(86)90040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIROIR B.P. Mediators of septic shock: New approaches for interrupting the endogenous inflammatory cascade. Crit. Care Med. 1993;25:780–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALL S., TURCATO S., CLAPP L. Abnormal activation of K+ channels underlies relaxation to bacterial lipopolysaccharide in rat aorta. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;224:184–190. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALUSHKA P.V., REINES H.D., BARROW S.E., BLAIR I.A., DOLLERY C.T., RAMBO W., COOK J.A., WISE W.C. Elevated plasma 6-keto-prostaglandin F1α in patients in septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 1985;13:451–453. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198506000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOSAKA H., WATANABE M., YOSHIHARA H., HIRADA N., SHIGA T. Detection of nitric oxide production in lipopolysaccharide-treated rats by ESR using carbon monoxide haemoglobin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992;184:1119–1124. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)90708-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOVACS R.J., NELSON M.T. ATP-sensitive K+ channels from aortic smooth muscle incorporated into planar lipid bilayers. Am. J. Physiol. 1991;26:H604–H609. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.2.H604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANDRY D.W., OLIVER J.A. The ATP-sensitive K+ channel mediates hypotension in endotoxemia and hypoxic lactic acidosis in dog. J. Clin. Invest. 1992;89:2071–2074. doi: 10.1172/JCI115820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCULLOCH A.I., RANDALL M.D. Modulation of vasorelaxant responses to potassium channel openers by basal nitric oxide in the rats isolated superior mesenteric arterial bed. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:859–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MITCHELL J.A., KOHLHAAS K.L., SORRENTINO R., WARNER T.D., MURAD F., VANE J.R. Induction by endotoxin of nitric oxide synthase in the rat mesentery: lack of effect on action of vasoconstrictors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;109:265–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIYOSHI H., NAKAYA Y., MORITOKI H. Nonendothelial-derived nitric oxide activates the ATP-sensitive K+ channel in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. FEBS Lett. 1994;345:47–49. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00417-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURPHY M.E., BRAYDEN J.E. Nitric oxide hyperpolarizes rabbit mesenteric arteries via ATP-sensitive potassium channels. J. Physiol. 1995;486:47–58. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKANO T., ARITA H. Enhanced expression of group II phospholipase A2 in the tissues of endotoxin shock in rats and its suppression by glucocorticoids. FEBS Lett. 1990;273:23–26. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81042-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NELSON M.T., QUAYLE J.M. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;268:C799–C822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARRILLO J.E., PARKER M.M., NATANSON C., SUFFREDINI A.F., DANNER R.L., CUNNION R.E., OGNIBENE F.P. Septic shock in humans. Advances in the understanding of pathogenesis, cardiovascular dysfunction, and therapy. Ann. Intern. Med. 1990;113:227–242. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-3-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARRATT J.R.Alterations in vascular reactivity in sepsis and endotoxaemia Update in Intensive Care 19898Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 299–312.ed. Vincent J.L. pp [Google Scholar]

- SCHALLER M.D., WAEBER B., NUSSBERGER J., BRUNNER H.R. Angiotensin II, vasopressin, and sympathetic activity in conscious rat with endotoxemia. Am. J. Physiol. 1985;249:H1086–H1092. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.249.6.H1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMEDEGÅRD G., CUI L.X., HUGLI T.E. Endotoxin-induced shock in the rat. A role for C5a. Am. J. Pathol. 1989;135:489–497. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH J.J., KAMPINE J.P.Pressure and flow in the arterial and venous systems Circulatory Physiology 1984Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins; 90–109.(II edn.). ed. Smith, J.J. & Kampine, J.P. pp [Google Scholar]

- STANDEN N.B., QUAYLE J.M., DAVIES N.W., BRAYDEN J.E., HUANG Y., NELSON M.T. Hyperpolarizing vasodilators activate ATP-sensitive K+ channels in arterial smooth muscle. Science. 1989;245:177–180. doi: 10.1126/science.2501869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SWIERKOSZ T.A., MITCHELL J.A., WARNER T.D., BOTTING R.M., VANE J.R. Co-induction of nitric oxide synthase and cyclo-oxygenase: interactions between nitric oxide and prostanoids. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;114:1335–1342. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13353.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAGUCHI H., HEISTAD D.D., CHU Y., RIOS C.D., OOBOSHI H., FARACI F.M. Vascular expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase is associated with activation of Ca++- dependent K+ channels. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;279:1514–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THIEMERMANN C. The role of L-arginine: nitric oxide pathway in circulatory shock. Adv. Pharmacol. 1994;28:45–79. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60493-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THIEMERMANN C., VANE J.R. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis reduces the hypotension induced by bacterial lipopolysaccharides in the rat in vivo. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1990;182:591–595. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90062-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAKABAYASHI I., HATAKE K., KAKISHITA E., NAGAI K. Diminution of contractile response of the aorta from endotoxin-injected rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1987;141:117–122. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(87)90417-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU C.C., THIEMERMANN C., VANE J.R. Glibenclamide-induced inhibition of the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in cultured macrophages and in the anaesthetised rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;114:1273–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13343.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]