Abstract

We have mutated a conserved leucine in the putative membrane-spanning domain to serine in human GABAA β2 and investigated the actions of a number of GABAA agonists, antagonists and modulators on human α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s compared to wild type α1β2γ2s GABAA receptors, expressed in Xenopus oocytes.

The mutation resulted in smaller maximum currents to γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) compared to α1β2γ2s receptors, and large leak currents resulting from spontaneous channel opening. As reported, this mutation significantly decreased the GABA EC50 (110 fold), and reduced desensitization. Muscimol and the partial agonists 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[5,4-c]pyridin-3-ol (THIP) and piperidine-4-sulphonic acid (P4S) also displayed a decrease in EC50.

In addition to competitively shifting GABA concentration response curves, the antagonists bicuculline and SR95531 both inhibited the spontaneous channel activity on α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s receptors, with different degrees of maximum inhibition.

The effects of a range of allosteric modulators, including benzodiazepines and anaesthetics were examined on a submaximal GABA concentration (EC20). Compared to wild type, none of these modulators potentiated the EC20 response of α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s receptors, however they all directly activated the receptor in the absence of GABA.

To conclude, the above mutation resulted in receptors which exhibit a degree of spontaneous activity, and are more sensitive to agonists. Benzodiazepines and other agents modulate constitutive activity, but positive modulation of GABA is lost. The competitive antagonists bicuculline and SR95531 can also act as allosteric channel modulators through the same GABA binding site.

Keywords: GABAA receptor, benzodiazepine, oocyte, ion-channel, modulator, leucine, inverse agonist

Introduction

GABAA receptors form part of the ligand-gated ion-channel superfamily, comprising other anion channels such as glycine receptors, as well as cation channels, such as the nicotinic acetylcholine and 5HT3 receptors. These receptors all share a common physical structure thought to consist of four transmembrane (TM) domains, a large N-terminal domain and an intracellular loop between putative TM3 and TM4. Most are multimeric receptors formed from at least two to four different subunits, which can have dramatic effects on the pharmacology of individual receptor subtypes. The GABAA receptors form the major mechanism for synaptic inhibition in the central nervous system, and are ubiquitously spread throughout the brain. They are made up from α, β γ, δ and ε subunits (see Sieghart, 1995; McKernan & Whiting, 1996; Whiting et al., 1995; 1997) which assemble into a presumed pentameric arrangement to form a transmembrane pore, which gates chloride on receptor activation.

The high affinity binding of radiolabelled agonists for ligand-gated ion channels usually contrasts with the relatively low functional affinity they have at the receptor and this has recently been compared on recombinant GABAA receptors (Ebert et al., 1997). The binding affinity (pKi) for GABA agonists such as muscimol, GABA, and 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[5,4-c]pyridin-3-ol (THIP) is generally two to three orders of magnitude higher than the pEC50's measured electrophysiologically (Ebert et al., 1997). One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that [3H]-muscimol binding is measuring the intrinsic affinity of the agonist for its receptor binding-site, whereas the functional measure reflects activation of the entire receptor/ion channel complex, including the transduction process, probability of channel opening and desensitization.

Some evidence for this hypothesis comes from mutation of a conserved leucine in the putative membrane-spanning domain of several gated ion channels. Changes to this residue result in up to 1000 fold increased agonist sensitivity (Labarca et al., 1995; Chang et al., 1996), which would bring the functional EC50 close to the affinity measured by ligand binding. α1β2γ2 receptors are thought to be the most abundant receptor combination in the central nervous system (McKernan & Whiting, 1996). We have used this combination, and mutated the conserved leucine in human GABAA β2 to serine, and determined the consequences of this mutation on the actions of a number of GABAA agonists, antagonists and allosteric modulators compared to wild type α1β2γ2s GABAA receptors, expressed in Xenopus oocytes. A preliminary account of some of this work has been presented in abstract form (Thompson et al., 1998).

Methods

Oocyte expression

Adult female Xenopus laevis were anaesthetized by immersion in a 0.4% solution of 3-aminobenzoic acid ethylester for 30–45 min (or until unresponsive). Ovary tissue was removed via a small abdominal incision and Stage V and Stage VI oocytes were isolated with fine forceps. After mild collagenase treatment to remove follicle cells (Type IA, 0.5 mg ml−1, for 6 mins), the oocyte nuclei were directly injected with 10–20 nl of injection buffer (in mM: NaCl 88, KCl 1, HEPES 15, at pH 7, filtered through nitro-cellulose) containing different combinations of human GABAA subunit cDNAs (20 ng μl−1) engineered into the expression vector pCDM8 or pcDNAI/Amp. Following incubation for 24–72 h, oocytes were placed in a 50 μl bath and perfused at 4–6 ml min−1 with modified Barth's medium (MBS) consisting of (in mM) NaCl 88, KCl 1, HEPES 10, MgSO4 0.82, Ca(NO3)2 0.33, CaCl2 0.91, NaHCO3 2.4, at pH 7.5. Cells were impaled with two 1–3 MΩ electrodes containing 2 M KCl and voltage-clamped between −40 and −70 mV.

Experimental design

In all experiments drugs were applied in the perfusate until the peak of the response was observed. Non-cumulative concentration-response curves to agonists were constructed with an interval of 3 min between each agonist application.

Curves were fitted using a non-linear square-fitting program to the equation f(x)=BMAX/[1+(EC50/x)n] where x is the drug concentration, EC50 is the concentration of drug eliciting a half-maximal response and n is the Hill coefficient. The effects of GABAA receptor modulators were examined on control GABA EC20 responses with a preapplication time of 30 s.

Drugs

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA, Sigma), muscimol (Sigma, Poole, U.K.), 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[5,4-c]pyridin-3-ol hydrochloride (THIP, Tocris, Bristol, U.K.) and piperidine-4-sulphonic acid (P4S, Sigma, Poole, U.K.) were prepared as a 1 M stock solutions in MBS. Stock solutions of flunitrazepam (10 mM, Sigma, Poole, U.K.), methyl 6,7-dimethoxy-4-ethyl-b-carboline-3-carboxylate (DMCM, 10 mM, Research Biochemicals International, Poole, U.K.), methyl-β-carboline-3- carboxylate (β-CCM, 10 mM Research Biochemicals International, Poole, U.K.), CL218,872 (100 mM, Lederle, NS, U.S.A.), Ro15-1788 (10 mM, synthesized by the Chemistry Department at MSD, Harlow, Essex, U.K.), zolpidem (10 mM, Research Biochemicals International, Poole, U.K.), 5α-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one (10 mM, Sigma, Poole, U.K.), loreclezole (100 mM, a kind gift from Janssen, Burse, Belgium), SR95531 (100 mM, Research Biochemicals International, Poole, U.K.) picrotoxin (100 mM, Sigma, Poole, U.K.), bicuculline methiodide (100 mM, Sigma, Poole, U.K.) were prepared in 100% dimethylsulphoxide. Pentobarbitone was obtained from Rhône Mérieux, Harlow, U.K. (Sagatal for injection containing 60 mg ml−1 pentobarbitone sodium) and 2,6-diisopropyl phenol (propofol) was obtained from Aldrich, Poole, U.K. both were supplied as solutions. The concentrates were diluted into MBS. The maximal final vehicle concentration of DMSO was 0.3% v v−1 which had no effect alone or on GABA currents.

Data analysis

All data are shown as means±s.e.mean. Differences between means were evaluated by Student's t-test and considered significant if P<0.05.

Results

Changes in gating and response to agonists

Significantly smaller currents to a maximum concentration of GABA were observed in α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s receptors (92.5±6.3 nA n=62) compared to α1β2γ2s (2164±304 nA n=17). The mutant receptors also displayed a greater leak current (between 200–400 nA) compared to the wild type (between 30–100 nA), when voltage-clamped at −70 mV. Current-voltage plots of the required holding current in α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s revealed this leak current to have a reversal potential of −28.5±3.9 mV (n=4). This leak current was compared to that in oocytes expressing wild type receptors (Figure 1), and suggested a significant proportion of the receptors were spontaneously open. This current was in most cases larger than the GABA elicited current when clamped at −70 mV, (223±25 nA (n=15) vs 85±8 nA (n=15)) and could be blocked by picrotoxin. Interestingly, this constitutive activity showed a very slow drift to less negative holding current as can be seen in Figures 5, 6 and 7, the reason for this is unknown. One possible explanation could be the slow redistribution of chloride through the open channels when clamped at −70 mV. The current voltage relationship for GABA revealed a reversal potential of −26.3±3.9 mV (n=4) for α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s which was not significantly different from −21.3±4.23 mV (n=5) for α1β2γ2s. β2ΔL259S when expressed alone did not result in constitutively active channels suggesting that the subunit alone cannot form functional ion channels.

Figure 1.

Current-voltage plots for the leak currents present in oocytes expressing α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s (n=4) and wild type α1β2γ2s receptors (n=4). The current voltage relationship for the GABA current on α1β2γ2s receptors (n=4) determined by applying the GABA EC50 concentration at different holding potentials is included for comparison. Reversal potentials were not significantly different and corresponded with ECl in oocytes.

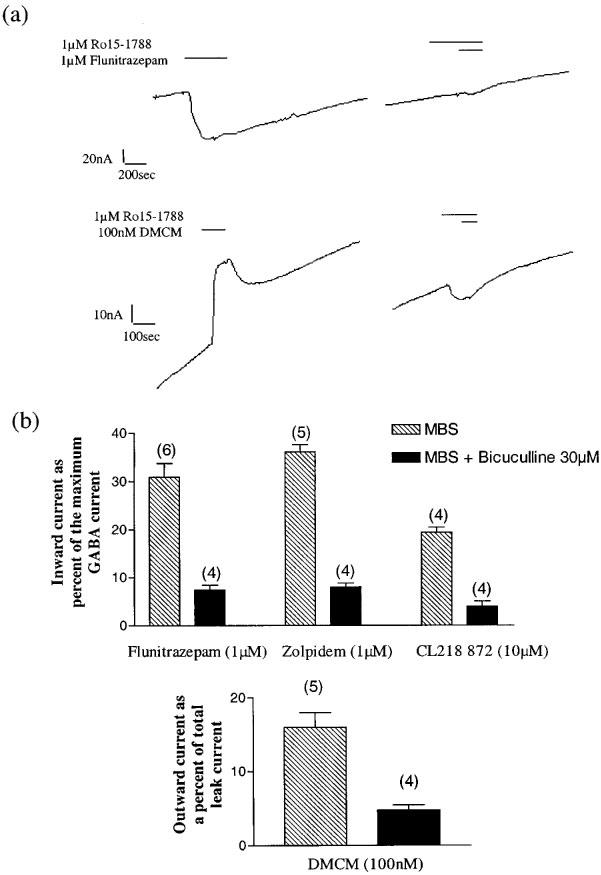

Figure 5.

(a) Directly activated currents on α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s receptors elicited by both flunitrazepam (1 μM) and DMCM (100 nM) are completely inhibited by co-application of 1 μM Ro15-1788. The apparent inward current to Ro15-1788 following DMCM is most likely due to the very slow dissociation of previously applied DMCM, as no currents were observed when Ro15-1788 was applied alone. Data represents a typical recording from at least four oocytes. (b) Directly activated currents by flunitrazepam (1 μM), zolpidem (1 μM) and CL218,872 (10 μM) are inhibited by co-application of 30 μM bicuculline (P<0.001). Inward currents were normalized to maximum GABA currents. Drugs were applied in either standard saline solution (MBS) or 30 μM bicuculline. The direct outward currents elicited by DMCM (100 nM), here normalized to the full blockade seen with picrotoxin, are also blocked by 30 μM bicuculline (P<0.005). Data represents mean±s.e.mean of the n numbers indicated above each bar.

Figure 6.

Potentiation of the GABA EC20 response by the benzodiazepine ligands, flunitrazepam (1 μM), zolpidem (1 μM) and CL218,872 (10 μM), and inhibition by DMCM on wild type α1β2γ2s receptors and on oocytes expressing α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s in the presence of 30 μM bicuculline to block the constitutive channel activity. Data represents the mean±s.e.mean from the number of oocytes indicated above each bar. Potentiation by flunitrazepam, zolpidem and CL218,872 were all significantly different (P<0.05) between the two receptors, while inhibition by the inverse agonists DMCM and β-CCM were not significantly different.

Figure 7.

(a) Concentration-response curves for the direct receptor activation of wild type α1β2γ2s (n=9) receptors or α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s (n=4) receptors by pentobarbitone. Data is expressed relative to a maximum GABA evoked current, and represents the mean±s.e.mean. For α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s, the curve was fitted through points up to 100 μM only. (b) Effects of 3 and 100 μM pentobarbitone on a GABA EC20 response in either wild type α1β2γ2s receptors or α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s receptors.

As previously reported, this mutation decreased the GABA EC50 (110 fold) resulting in mean EC50 values of 182±61 nM (n=6) on α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s compared to 20±3 μM on α1β2γ2s (n=7) (Figure 2a). The full agonist muscimol also exhibited a leftward shift in EC50 with a value of 0.1±0.03 μM (n=4) on α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s receptors compared to 3.8±0.9 μM (n=4) on α1β2γ2s (data not shown). The partial agonists THIP and piperidine-4-sulphonic acid P4S also displayed a similar decrease in EC50 (90 and 70 fold respectively). The constrained GABA analogue THIP, had efficacy of 79±2% (n=4) on wild type, and this was unchanged on the mutant receptor (74±10% (n=4)) (Figure 2b). P4S however, which had a lower efficacy of 37±5% on α1β2γ2, showed a significant increase in its maximum efficacy on the mutant α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s (71±3% (n=4), P<0.001) (Figure 2c), suggesting that mutation at the ion channel gate can influence the efficacy of some GABA partial agonists.

Figure 2.

Concentration-response curves to (a) GABA, (b) THIP and (c) P4S on oocytes expressing α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s and wild type α1β2γ2s GABAA receptors. Data points are the means±s.e.mean of four or more oocytes.

There were also marked differences in the rate of desensitization of GABAA receptors containing the β2ΔL247S mutant. The desensitization following maximum GABA concentrations was fitted best in both wild type and mutant by a single exponential curve. The mutation slowed the rate of desensitization (t½) from 49.7±10.2 s (n=4) in wild type to 143±17.5 s in the mutant receptor (n=4).

Differences in antagonist behaviour

The non-competitive GABAA antagonist picrotoxin (100 μM) produced apparent outward currents (+181±17 nA, n=41) in the absence of GABA, suggesting block of the spontaneously open channels or leak current measured when voltage-clamped at −70 mV. The competitive antagonists bicuculline and SR95531 also both produced apparent outward currents on α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s receptors. The degree of block of constitutive activity to increasing concentrations of competitive antagonists bicuculline and SR95531 were normalized to the outward current produced by picrotoxin, which presumably reflected complete block of all channels. Bicuculline produced a maximum inhibition of 85±4% (n=4), while SR95531 only produced a maximal inhibition of 13±1% (n=4) (Figure 3a). The pIC50's of 5.5±0.09 (n=4) for bicuculline and 6.8±0.05 (n=4) for SR95531 correlate well with the pKi's for competitive antagonism of wild type α1β2γ2 GABA receptors (Ebert et al., 1997). The block of constitutive activity by bicuculline could be reversed by co-application by SR95531 (Figure 3b), showing for the first time, the competitive nature of these compounds. In addition to producing a block of the leak current, the two antagonists also competitively shifted GABA concentration response curves to the right, as would be expected. The pKi's derived from this shift for SR95531 and bicuculline were 6.9±0.06 (n=4) and 5.0±0.09 (n=4) respectively, similar to those at blocking spontaneously open channels, and similar to wild type α1β2γ2 receptors (SR95531, 6.5±0.02 (n=4), and bicuculline, 5.6±0.05 (n=4)).

Figure 3.

(a) Concentration-response curves for the inhibitory effect of bicuculline and SR95531 on the leak conductance present in oocytes expressing α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s receptors. The outward currents to the competitive antagonists were normalized to the outward current produced by 100 μM picrotoxin, which reflected complete block of all channels. Bicuculline produced a maximum inhibition of 85±4% (n=4), while SR95531 only produced a maximal inhibition of 13±1% (n=4). (b) Outward currents on α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s receptors elicited by 30 μM bicuculline could be inhibited by co-application of 10 μM SR95531, demonstrating the competitive nature of these two antagonists. The outward current to 100 μM picrotoxin on the same cell is shown for comparison.

Allosteric modulation by benzodiazepines

Five benzodiazepine site ligands were selected for the study, reflecting structurally diverse compounds, as well as differing levels of intrinsic efficacy, ranging from full agonists such as flunitrazepam, through partial agonist such as CL218,872 to the inverse agonist, DMCM. The modulation of submaximal GABA concentrations (EC20) by maximally effective concentrations of each compound were examined. While exhibiting no direct effects, but marked modulation of GABA currents on wild type α1β2γ2s receptors, the EC20 response of α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s receptors was not potentiated by any of these modulators, however they all produced apparent direct effects in the absence of GABA (Figure 4). The benzodiazepine inverse agonists DMCM and β-CCM, produced outward currents in the absence of GABA, but again did not modulate the GABA EC20. These direct effects of benzodiazepines were blocked by the benzodiazepine antagonist Ro15-1788 (1 μM), and by 30 μM bicuculline (Figure 5), suggesting that these currents resulted from modulating the constitutively active channels already present. Using 30 μM bicuculline the constitutive activity could be blocked, however this did not restore the potentiation of GABA currents by benzodiazepine agonists (Figure 6). Interestingly, it did restore the inverse modulation of the GABA EC20 by DMCM and β-CCM (Figure 6).

Figure 4.

Effects of four benzodiazepine modulators with differing efficacy on wild type α1β2γ2s receptors and α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s receptors. The figure illustrates (a) the full agonist flunitrazepam, (b) the partial agonist CL-218,872, (c) the α1-selective full agonist zolpidem and (d) the full inverse agonist DMCM. The compounds are all benzodiazepine ligands and as well as representing the range of efficacies also show structural diversity. On α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s receptors these benzodiazepines all produced currents in the absence of GABA, agonists producing inward currents while the inverse agonist DMCM produced an outward current. Data represent typical recordings from four or more oocytes.

Allosteric modulation via anaesthetic and other binding sites on the receptor

The barbiturate pentobarbitone potentiates the wild type receptor at concentrations between 10 and 100 μM, and at higher concentrations directly activates the receptor. At the α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s receptors, concentration response curves for the direct activation by pentobarbitone showed a significant, (P<0.001) 10 fold decrease in EC50 compared to wild type (Figure 7a), hence the leftward shift seen with agonists was not restricted to those active at the GABA binding site. This is unlike the effects of mutations in the N-terminal GABA binding domains, which do not affect pentobarbitone activation (Amin & Weiss, 1993). The potentiation of the GABA EC20 response observed in wild type receptors with pentobarbitone was absent in the mutant, and as can be seen from Figure 7b, 3 μM pentobarbitone was equally ineffective at potentiating a GABA EC20. This suggests that there is not a corresponding shift in EC50 for potentiation on α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s. Similar to benzodiazepine modulation, potentiation by pentobarbitone was not restored when constitutive activity was inhibited using 30 μM bicuculline (data not shown). While pentobarbitone produced the largest direct activation on α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s receptors (79±6% of maximum GABA, n=4), this was compromised by the marked inhibition seen at concentrations over 100 μM.

The neuroactive steroid 5α-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one potentiated α1β2γ2s GABAA receptors at 1 μM with no marked direct activation. In contrast large direct currents (36±4% of maximum GABA, n=4) were observed on α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s receptors (Figure 8a), and no modulation of the GABA EC20. Similar results were obtained with the β2/3-subunit selective compound loreclezole (10 μM) (Figure 8b) which produced the smallest direct current (12±1% of maximum GABA, n=4) on α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s receptors. The anaesthetic compound propofol (10 μM) produced a very marked direct current (49.5±3.9% of maximum GABA, n=4) (Figure 8c), reducing the effect of any further GABA receptor activation by coapplication of GABA in the presence of propofol.

Figure 8.

Effects of other GABAA receptor allosteric modulators on wild type α1β2γ2s receptors and α1β2ΔL259Sγ2s receptors. The figure illustrates typical modulation of the EC20 response to GABA by (a) the steroid 5α-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one (1 μM) (b) loreclezole (10 μM) and (c) the anaesthetic compound propofol (10 μM). The traces represent data from at least four different experiments on each modulator.

Discussion

The structure of the putative transmembrane domain 2 (TM2) of the GABAA receptor is thought to be close to that of other members of the ligand-gated ion-channel family. Studies using the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor have demonstrated that the 9′ leucine appears to be an important residue forming the ion channel gate. Mutation of this residue increases apparent acetylcholine sensitivity and reduces desensitization. In studies on multimeric receptors mutation of each individual subunit confers approximately a 10 fold increase in agonist sensitivity (Labarca et al., 1995; Filatov & White, 1995). This appears to be the case for GABA receptors also (Chang et al., 1996), and has been utilized to determine receptor stoichiometry. Here, we have studied the effects of this mutation in more detail, and have demonstrated that as well as increasing GABA sensitivity, mutation of the 9′ leucine to serine produces corresponding increased sensitivity to partial agonists and an increased efficacy for P4S. As well as increasing sensitivity to activation by GABA, other allosteric compounds, which directly operate the channel such as pentobarbitone, are also more potent, with a corresponding increase in efficacy. This supports the hypothesis that the agonist binding-site itself is not affected by this mutation. It was apparent that the mutation caused a dramatic decrease in receptor desensitization in response to GABA. This observation is also common to studies on other ligand gated ion channels mutated at this position. The nicotinic α7 (Revah et al., 1991; Bertrand et al., 1992), muscle nicotinic receptors (Labarca et al., 1995), and 5HT-3 receptors (Yakel et al., 1993) all show reduced desensitization when the corresponding leucine mutation is made. This observation would support the hypothesis that a normally desensitized state of the receptor becomes conducting when leucine is mutated to a serine.

In addition to increased sensitivity to agonists, the mutant channels produced marked spontaneous openings, reflected in large leak currents, which reversed at the same potential as GABA, and were blocked by the non-competitive inhibitor picrotoxin. This spontaneous channel activity is similar to that seen on expression of GABAA β1 homomeric receptors (Sigel et al., 1989; Krishek et al., 1996), which are also sensitive to picrotoxin, and has also been reported for equivalent mutations in the GABA ρ1 receptor (Pan et al., 1997; Chang & Weiss, 1998). On injection of the GABAA β2ΔL259S alone, no currents were observed to GABA, and no leak conductances were present, suggesting that unlike β1 and ρ1 this construct did not form homomeric channels. Unlike ρ1, the α1β2ΔL259Sγ2 receptor did not exhibit inhibition of constitutive opening by low concentrations of GABA. Mutation of the β1Leu259 to Thr has been reported to cause constitutive channel opening when expressed with α1 in Sf9 cells, but in this case GABA did not activate the receptor, and unlike the results here were not blocked by picrotoxin or bicuculline (Tierney et al., 1996). The equivalent mutation in the α1 subunit did result in GABA currents when expressed with β1, but in contrast to Chang et al. (1996) no decrease in EC50 was reported.

It was apparent that the mutation of this residue dramatically affected the level of receptor expression. Maximum currents to GABA were significantly reduced with receptors containing the mutant β-subunit. This was consistent with the findings of Tierney et al. (1996) and Chang et al. (1996) who also described a decrease in expressed receptor following L'9T in either the α1 in β1 subunit. It is, however, unlike that found with equivalent mutants in the nicotinic receptor where no reduction in current size was observed (Bertrand et al., 1992).

In order to demonstrate that antagonist affinity remained unchanged by this mutation, we compared the competitive antagonists bicuculline and SR95531. Both these compounds produced shifts of the GABA concentration response curve to the right as expected, with pKi's of 5.0 and 6.9 respectively, similar to that on wild type receptors. In contrast to wild type receptors, however bicuculline produce marked outward currents on the mutant receptors, inhibiting the constitutively active channels. The IC50 for this effect corresponded exactly with its pKi, suggesting this action to be via the same site. SR95531 showed only partial inhibition of the constitutive channel activity, and antagonized the effect of bicuculline, indicating that this compound has less inverse activity than bicuculline and competes at the same site. This suggests bicuculline is acting as an allosteric inhibitor or inverse agonist at the GABA site, confirming the hypothesis previously suggested by Ueno et al. (1997) who showed allosteric inhibition of pentobarbitone currents by bicuculline on rat α1β2γ2 GABAA receptors. The levels of inverse activity for bicuculline and SR95531 on receptors containing β2ΔL259S correlate well with that shown on wild type pentobarbitone gated currents, providing further evidence that bicuculline can allosterically inhibit channel activity.

The GABAA receptor is notable for its sensitivity to modulation by benzodiazepines. We compared the action of several ligands with different intrinsic efficacy at the benzodiazepine site, and found that modulation of the GABA EC20 response was lost for both agonist and inverse agonists following mutation of β2L259. It was clear however, that these compounds maintained activity at the binding site, as all compounds showed apparent direct activation of the receptor, with efficacy correlating with that at the benzodiazepine site, including outward currents in response to the inverse agonist DMCM. All these responses were completely inhibited by flumazenil, suggesting that the BZ site remained unaffected by the mutation. This is in agreement with the hypothesis that the BZ binding site is located at the α/γ interface (Sigel & Buhr, 1997; Wingrove et al., 1997). One possible explanation for these BZ mediated currents is that the spontaneous channel activity is being modulated by benzodiazepines, producing apparent BZ activated currents. This appears to be the case, as blocking the spontaneous activity with bicuculline, and applying benzodiazepines significantly reduces the benzodiazepine-mediated currents. It does not, however, restore the potentiation of GABA-mediated currents, suggesting that the abolition of allosteric modulation is not due to the presence of constitutively open channels. Interestingly the negative modulation by two inverse agonists, DMCM and β-CCM, is observable in the presence of bicuculline, which indicates that it is only the positive allosteric modulation that is affected.

The majority of anaesthetics exhibit marked potentiation of GABAA receptors and at high concentrations directly activate the receptor (Thompson et al., 1996; Pistis et al., 1997). Here we have studied the effects of pentobarbitone, propofol and the anaesthetic steroid 5α-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one, as well as the β2/3-subunit selective modulator loreclezole (Wafford et al., 1994). As well as abolishing benzodiazepine modulation the mutation also abrogates potentiation by any of these modulators, but again the presence of constitutively active channels reveals apparent direct effects with these compounds, most prominent with pentobarbitone, where the EC50 is decreased by 10 fold. As a consequence 100 μM pentobarbitone alone produces almost a saturating response, overwhelming any additional GABA mediated response, resulting in an apparent decrease in GABA modulation. Reducing the concentration of pentobarbitone to one that did not directly activate the receptor produced no potentiation, demonstrating that the EC50 for potentiation was not shifted in parallel with that for direct activation. In contrast loreclezole produced only a small direct current (12% of maximum GABA) but did not potentiate GABA. Similar experiments performed in the presence of bicuculline to abolish constitutive activity did not restore anaesthetic potentiation.

The current hypothesis on the role of this leucine in ligand-gated ion channel activity is that it lies at the most constricted position in the channel, where the transmembrane-lining helices are kinked (Unwin, 1995). As the channel is likely to be pentameric the equivalent residues from each subunit line up to form a cluster that can be translocated on agonist binding to the open channel conformation, and back again on channel closure. The introduction of a polar side chain in serine or threonine destabilizes the cluster, reducing the channel closure rate and favours the open conformation. This hypothesis explains the reduced desensitization and constitutively open channels. Other evidence from cysteine substitution experiments in nicotinic (Akabas et al., 1994) and GABAA receptors (Xu & Akabas, 1996) suggests that the gate may be more cytoplasmic than the 9′ residue, based on modification of residues C-terminal to the leucine.

Here we show that this mutation dramatically affects allosteric coupling of GABA activation to modulatory sites on the GABAA receptor that is not due to the presence of constitutive open channels. As the GABA EC50 is shifted to the left, increasing the likelihood of channel opening, it approaches that measured by radioligand binding or the highest achievable affinity. If the mechanism of allosteric potentiation is to increase channel activity either by increasing channel opening frequency or mean open time, there must be a limit beyond which no further leftward shift is possible. This window could be defined as that between the functional EC50 and that measured by radioligand binding. By making this mutation, and shifting the receptor EC50 closer to the intrinsic binding affinity, it is likely that no further shift is possible and positive allosteric potentiation is reduced. If this is the case then positive allosteric modulators would be inactive but negative allosteric modulation would still be possible. This does appear to be the case with the inverse agonists DMCM and β-CCM, which in the presence of bicuculline produce an effect identical to the wild type receptor, although it does not explain the lack of effect of DMCM in the absence of bicuculline.

There has been much speculation on the role played by the conserved leucine. One possible explanation is that a normally desensitized receptor state becomes conducting in the mutant, and authors have identified additional conductance states in the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor containing this mutant (Revah et al., 1991; Bertrand et al., 1992). This explanation however, does not fit with recent observations of agonist induced closure of constitutively open channels (Pan et al., 1997; Chang & Weiss, 1998). The evidence here and from others does suggest that it dramatically affects the activation and desensitization of the receptor through any binding-site which can open the channel. It also shifts the receptor into a state that can no longer be positively modulated by allosteric agonists, while these compounds are clearly still binding to their respective sites. Further studies into the kinetics and single-channel properties of these channels will reveal more about the relationship between receptor binding and transduction to open channels.

Abbreviations

- BZ

benzodiazepine

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulphonic acid

- THIP

4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[5,4-c]pyridin-3-ol

- P4S

piperidine-4-sulphonic acid

- TM

transmembrane-spanning region

- DMCM

dimethoxy-4-ethyl-β-carboline-3-carboxylate

References

- AKABAS M.H., KAUFMANN C., ARCHDEACON P., KARLIN A. Identification of acetylcholine receptor channel-lining residues in the entire M2 segment of the α-subunit. Neuron. 1994;13:919–927. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90257-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AMIN J., WEISS D.S. GABAA receptor needs two homologous domains of the β subunit for activation by GABA but not by pentobarbital. Nature. 1993;366:565–569. doi: 10.1038/366565a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERTRAND D., DEVILLIERS-THIERY A., REVAH F., GALZI J.-L., HUSSY N., MULLE C., BERTRAND S., BALLIVET M., CHANGEUX J.-P. Unconventional pharmacology of a neuronal nicotinic receptor mutated in the channel domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:1261–1265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANG Y., WANG R., BAROT S., WEISS D.S. Stoichiometry of a recombinant GABAA receptor. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:5415–5424. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-17-05415.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANG Y., WEISS D.S. Substitutions of the highly conserved M2 leucine create spontaneously opening ρ1 γ-aminobutyric acid receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:511–523. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EBERT B., THOMPSON S.A., SUONATSOU K., MCKERNAN R., KROGSGAARD-LARSEN P., WAFFORD K.A. Differences in agonist/antagonist binding affinity and receptor transduction using recombinant human γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;52:1150–1156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FILATOV G.N., WHITE M. The role of conserved leucines in the M2 domain of the acetylcholine receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;48:379–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRISHEK B.J., MOSS S.J., SMART T.G. Homomeric beta 1 gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor-ion channels: evaluation of pharmacological and physiological properties. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;49:494–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LABARCA C., NOWAK M., ZHANG H., TANG L., DESHPANDE P., LESTER H. Channel gating governed symmetrically by conserved leucine residues in the M2 domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature. 1995;376:514–516. doi: 10.1038/376514a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCKERNAN R.M., WHITING P.J. Which GABAA-receptor subtypes really occur in the brain. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:139–143. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)80023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAN Z.-H., ZHANG D., ZHANG X., LIPTON S.L. Agonist-induced closure of constitutively open γ-aminobutyric acid channels with mutated M2 domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:6490–6495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PISTIS M., BELELLI D., PETERS J.A., LAMBERT J.J. The interaction of general anaesthetics with recombinant GABAA and glycine receptors expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes: a comparative study. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:1707–1719. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REVAH F., BERTRAND D., GALZI J.-L., DEVILLIERS-THIERY A., MULLE C., HUSSY N., BERTRAND S., BALLIVET M., CHANGEUX J.-P. Mutations in the channel domain alter desensitization of a neuronal nicotinic receptor. Nature. 1991;353:846–849. doi: 10.1038/353846a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIEGHART W. Structure and pharmacology of γ-aminobutyric acid A receptor subtypes. Pharmacol. Rev. 1995;47:181–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIGEL E., BAUR R., MALHERBE P., MOHLER H. The rat beta 1-subunit of the GABAA receptor forms a picrotoxin-sensitive anion channel open in the absence of GABA. FEBS Lett. 1989;257:377–379. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81576-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIGEL E., BUHR A. The benzodiazepine binding site of GABAA receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1997;18:425–429. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMPSON S.A., WHITING P.J., WAFFORD K.A. Alpha subunits influence the action of pentobarbital on recombinant GABAA receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:521–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15221.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMPSON S.A., SMITH M.Z., WINGROVE P.B., WHITING P.J., WAFFORD K.A. A channel mutant of GABAA receptors reveals changes in allosteric modulation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;123 suppl:196P. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TIERNEY M.L., BIRNIR B., PILLAI N.P., CLEMENTS J.D., HOWITT S.M., COX G.B., GAGE P.W. Effects of mutating leucine to threonine in the M2 segment of α1 and β1 subunits of the GABAA α1β1 receptors. J. Membrane Biol. 1996;154:11–21. doi: 10.1007/s002329900128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UENO S., BRACAMONTES J., ZORUMSKI C., WEISS D.S., STEINBACH J.H. Bicuculline and gabazine are allosteric inhibitors of channel opening of the GABAA receptor. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:625–634. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00625.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNWIN N. Acetylcholine receptor channel imaged in the open state. Nature. 1995;373:37–43. doi: 10.1038/373037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAFFORD K.A., BAIN C.J., QUIRK K., MCKERNAN R.M., WINGROVE P.B., WHITING P.J., KEMP J.A. A novel allosteric modulatory site on the GABAA receptor β subunit. Neuron. 1994;12:775–782. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITING P.J., MCALLISTER G., VASILATIS D., BONNERT T.P., HEAVENS R., SMITH D., HEWSON L., O'DONNELL R., RIGBY M.R., SIRINATHSINGHJI D.J.S., MARSHALL G., THOMPSON S.A., WAFFORD K.A. Neuronal restricted RNA splicing regulates the expression of a novel GABA-A receptor subunit conferring atypical functional properties. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:5027–5037. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05027.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITING P.J., MCKERNAN R.M., WAFFORD K.A.Structure and pharmacology of vertebrate GABAA receptor subtypes International Review of Neurology 199538Academic Press: Burlington, MA, U.S.A.95–138.In: Bradley R.J. & Harris R.A. (eds) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WINGROVE P.B., THOMPSON S.A., WAFFORD K.A., WHITING P.J. Key amino acids in the γ subunit of the γ-aminobutyric acidA receptor that determine ligand binding and modulation at the benzodiazepine site. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;52:874–881. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.5.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XU M., AKABAS M.H. Identification of channel-lining residues in the M2 membrane-spanning segment of the GABAA receptor α1 subunit. J. Gen. Physiol. 1996;107:195–205. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAKEL J.L., LAGRUTTA A., ADELMAN J.P., NORTH R.A. Single amino acid substitution affects desensitization of the 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptor expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:5030–5033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]