Abstract

In this study, the mechanism of nicotine-induced hippocampal acetylcholine (ACh) release in awake, freely moving rats was examined using in vivo microdialysis.

Systemic administration of nicotine (0.4 mg kg−1, s.c.) increased the levels of ACh in hippocampal dialysates.

The nicotine-induced hippocampal ACh release was sensitive to the pretreatment of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) antagonists mecamylamine (3.0 mg kg−1, s.c.) and dihydro-β-erythrodine (DHβE; 4.0 mg kg−1, s.c.) as well as systemic administration of the dopamine (DA) D1 receptor antagonist SCH-23390 (R-(+)-7-chloro-8-hydroxy-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-benzazepine; 0.3 mg kg−1, s.c.).

Local perfusion of mecamylamine (100 μM), DHβE (100 μM) or SCH-23390 (10 μM) through microdialysis probe did not increase basal hippocampal ACh release.

Hippocampal ACh release elicited by systemic administration of nicotine (0.4 mg kg−1, s.c.) was antagonized by local perfusion of SCH-23390 (10 μM), but not by MEC (100 μM) or DHβE (100 μM).

Direct perfusion of nicotine (1 mM, but not 0.1 mM) increased hippocampal ACh levels; however, this effect was relatively insensitive to blockade by co-perfusion of either mecamylamine (100 μM) or SCH-23390 (10 μM).

These results suggest that nicotine-induced hippocampal ACh release occurs by two distinct mechanisms: (1) activation of nAChRs outside the hippocampus leading to DA release and subsequent ACh release involving a permissive DA synapse, and (2) direct action of nicotine within the hippocampus leading to ACh release via non-DA-ergic mechanism.

Keywords: Nicotine, hippocampal ACh release, microdialysis, SCH-23390, mecamylamine, neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

Introduction

Hippocampus receives its cholinergic innervation via the septo-hippocampal pathway and the release of ACh in this region has been postulated to be important in memory processes (Bartus et al., 1982). Decrements in the cholinergic function have long been recognized as an important component in Alzheimer's disease, with a reduction in choline acetyltransferase levels, the key enzyme in ACh synthesis, correlating with the severity of cognitive impairment (Perry et al., 1978; Wilcock et al., 1982). A better understanding of the regulation of ACh release in the central nervous system in general, and the hippocampal formation in particular, may lead to more effective therapies for the treatment of diseases involving decreased cholinergic function.

Hippocampal ACh release is modulated by a variety of synaptic inputs including the cholinergic, dopaminergic, serotonergic, histaminergic, and GABAergic systems (Day & Fibiger, 1994; Izumi et al., 1994; Mochizuki et al., 1994; Dazzi et al., 1995). The dopaminergic modulation of hippocampal ACh release has received considerable interest. Dopaminergic projections originating in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) innervate both the septal region and the hippocampus (Robinson et al., 1979; Scatton et al., 1980; Verney et al., 1985), providing an opportunity for DA-mediated effects at both ends of the septo-hippocampal pathway. Indeed, systemic administration of DA releasing agents as well as DA receptor agonists has been shown to cause an increase in ACh in hippocampal dialysates (Day & Fibiger, 1994; Imperato et al., 1993; Hersi et al., 1995). The proposed mechanism for this phenomenon involves activation of DA receptors. The precise role for DA receptor subtypes in the regulation of hippocampal ACh release appears to be controversial. Results from Day & Fibiger (1994) and Hersi et al. (1995) suggests a predominant role for D1 receptors while the results from Imperato et al. (1993) suggests the involvement of both D1 and D2 receptors. Septal application of dopaminergic antagonists increases cholinergic activity in the hippocampus (Robinson et al., 1979; Durkin et al., 1986), suggesting dopaminergic regulation of the septo-hippocampal pathway at the level of the cell body, possibly acting through gamna-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic interneurons (Wood, 1985). In addition to the effects of DA receptor antagonists in the septal region, direct hippocampal infusion of D1, but not D2, receptor agonists increased ACh levels in hippocampal dialysates (Hersi et al., 1995), suggesting an additional locus of action for dopamine is within the cholinergic terminal fields in the hippocampus. Thus, the dopaminergic regulation of hippocampal ACh release suggests that pharmacological agents that affect dopaminergic pathways may modulate hippocampal ACh release in vivo.

Nicotine, the prototypical agonist acting via the neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) is active in a variety of rodent and primate models of learning and memory (Levin, 1992; Buccafusco & Jackson, 1991), and improves cognitive function in Alzheimer's disease (Wilson et al., 1995). Nicotine-induced neurotransmitter release plays a major role in its behavioural effects such as the locomotor activity, improved vigilance and cognition enhancement (Wonnacott, 1997). Of particular relevance to the cognition enhancing effects of nicotine, among others, is the release of ACh and DA in relevant brain regions.

The nAChR regulation of DA release from striatum, nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex is extensively characterized in vitro (Sacaan et al., 1995; Clarke & Reuben, 1996) and in vivo (Mitsud et al., 1998; Nissel et al., 1994a,1994b; Imperato et al., 1986; Summers et al., 1994; 1997; Marshal et al., 1997). In addition, nicotine at behaviourally active doses (0.2–0.8 mg kg−1, s.c.) is known to increase norepinephrine (NE) and DA release from rat hippocampus (Brazell et al., 1991; Mitchell, 1993).

Nicotine is also known to regulate ACh release in hippocampus and cortex in vitro (Araujo et al., 1988; Wilkie et al., 1993; 1996; Rowell & Winkler, 1984; Beani et al., 1985; Meyer et al., 1987) and in vivo (Nordberg et al., 1989; Toide & Arima, 1989; Summers et al., 1994; 1997; Quirion et al., 1994; Tani et al., 1998). In in vitro assays employing synaptosomes or slices, nicotinic agonists have been shown to modulate ACh release from both the rat hippocampus and cortex. Nicotine-induced ACh release from hippocampal slices was sensitive to mecamylamine, d-tubocurarine and dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE), but not to tetrodotoxin, suggesting localization of the neuronal nAChRs on the cholinergic nerve terminals. The synaptosomal ACh release studies also support the localization of nAChRs on presynaptic terminals. In contrast to the hippocampus, other lines of evidence suggest either an indirect action or no effect for nicotine on ACh release in cortical synaptosomes (Meyer et al., 1987; Rowell & Winkler, 1984; Beani et al., 1985).

The pharmacology and the site of action of nAChR-mediated ACh release in hippocampus in vivo are yet to be fully characterized. Based on the knowledge that nicotine can induce the release of both DA and ACh in vivo, and that DA (D1) receptor activation results in the release of ACh in vivo, we speculated that nicotine-evoked DA release in vivo may contribute to nicotine-induced ACh release in the hippocampus. In the present study, the role DA in nicotine-induced hippocampal ACh release was examined. In addition, potential sites of action for nicotine-induced hippocampal ACh release were also investigated by systemic injection or local perfusion of nicotine into the hippocampus combined with perfusion of selected nAChR and DA antagonists directly into the hippocampus.

Methods

Chemicals

Mecamylamine HCl, DHβE HCl, SCH-23390 HCl and tetrodotoxin were obtained from Research Biochemical Inc. (RBI, Natick, MA, U.S.A.). (−)-Nicotine dihydrogen tartrate was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co, (Sigma, St Louis, MO, U.S.A.). All other chemicals were of the highest purity commercially available. All doses refer to mg kg−1, free base.

Animals

Male Sprague Dawley rats (160–200 g) were purchased from Harlan (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). All animals were housed in SIBIA Neurosciences, Inc. Vivarium. Rats were housed in plastic cages (3–4 rats per cage) with bedding. Animals were given free access to food and water throughout the study. Temperature and relative humidity were maintained at 22–24°C and 50–55%, respectively.

Microdialysis probes

The microdialysis probe assembly was constructed using the parts of the Push Pull Cannula System (Part No. C311GP/SPC; Plastics One, Roanoke, VA, U.S.A.) comprised of a stainless steel cannula (20G) attached to a plastic housing, a probe holder and a securing nut assembly. The stainless steel guide cannula were cut to 2 mm length and attached to the assembly. The loop-type dialysis probes attached to fused silica tubing and housed in a rigid shaft were purchased from ESA Inc. These probes had a 2 mm long semi-permeable membrane with a molecular weight cut-off of 6000 D. The probes were gently inserted into the probe assembly such that the entire length of the microdialysis membrane extends beyond the guide cannula. The fused silica tubing was secured to the plastic housing with an epoxy resin and allowed to cure for 24 h after which the guide cannula was removed.

Surgery

Rats were anaesthetized with isoflurane and mounted in a Kopf stereotaxic apparatus. The incisor bar was set at −3.3 mm (Paxinos & Watson, 1986). A midline incision was made to expose the skull and a hole was drilled at the following coordinates: AP, −3.5 mm and ML, 2.0 mm, (Paxinos & Watson, 1986). A 2.0 mm long stainless steel guide cannula, was inserted into the hole and was secured to the skull by three small machine screws anchored together by dental cement. A dummy cannula was inserted into the guide cannula to prevent clogging. The animals were removed from the sterotaxic frame and single housed for 3–7 days with free access to food and water.

Microdialysis experiments

On the day of the experiment, the rats were briefly anaesthetized with isoflurane and the dummy cannulae were removed. A microdialysis probe prepared as described above was inserted into the guide cannula. Under these conditions, the microdialysis probe extended 2 mm beneath the guide cannula. The animal was placed in a plastic bowl with a harness around its neck (CMA 120; CMA Microdialysis, Acton, MA, U.S.A.). The microdialysis probe was connected to a syringe pump through which a salt solution representing the ionic concentration of the cerebrospinal fluid (artificial CSF (in mM); NaCl 145; KCl 2.7; MgCl2 1.0 and CaCl2 1.2; pH 7.4; Moghaddam & Bunney, 1989) was pumped at a rate of 1.0 μl min−1. The cholinesterase inhibitor, neostigmine was included in the artificial CSF at a concentration of 100 nM. Twenty-minute fractions were collected and automatically injected on to a reverse-phase polymeric HPLC column via a sample loop and an auto-injector. The on-line microdialysis comprised of the following components: a CMA/100 microsyringe pump connected to a CMA/111 syringe selector.

HPLC methodology

The mobile phase (100 mM disodium hydrogen phosphate; 2.0 mM 1-octane sulphonic acid sodium salt; 0.005% reagent MB [ESA Inc. Chelmsford, MA, U.S.A.], pH=8.00 with phosphoric acid) was pumped using pump (ESA Model 580) through a polymeric reverse phase column (ACH-3, ESA Inc.) at a flow rate of 0.8 ml min−1. The effluent from the column was passed through an enzyme reactor containing immobilized acetylcholinesterase and choline oxidase (ACH-SPR, ESA Inc.). The HPLC column and the enzyme reactor were maintained at a constant temperature of 35°C. Acetylcholine and choline in microdialysis samples were converted into hydrogen peroxide which was detected by amperometric oxidation in an analytical cell containing a glassy carbon target electrode and a palladium reference electrode (ESA Model 5041). The oxidation potential was 250 mV and a Coulochem detector (ESA Model 5200A) detected the signal. The retention times for choline and acetylcholine under these conditions were 4 and 6 min respectively. The limit of detection for acetylcholine was less than 20 fmole on column.

Compound administration

On the day of the experiment, following insertion of the dialysis probe, 10–12 fractions were collected to establish baseline ACh release. Rats were then injected with test compound and samples were collected until the levels of ACh in the dialysate samples returned to baseline (3–5 h). The time of injection of test compounds is denoted by an arrow in the figures. When antagonists are examined, they were given 20 min before the injection of nicotine or saline as appropriate. For parenteral injection, compounds were dissolved in saline and the pH of the solution was adjusted by the addition of NaOH. Rats were injected subcutaneously with test compounds in a volume of 1.0 ml kg−1. For direct perfusion, the compounds were dissolved in artificial CSF, pH checked and adjusted as necessary, and perfused at a rate of 1 μl min−1. A horizontal line in the figures denotes the duration of the perfusion.

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed for statistical significance using two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Newman Keul's post hoc test of drug-treated animals vs the saline control or antagonist treatment (Graph Pad Prizm, San Diego, CA, U.S.A. and Sigma Stat Software, Jandel, San Rafel, CA, U.S.A.). Significance was considered to be a P value of <0.05. The effects of pharmacological treatments on ACh release were also assessed by determining the area under the curve (AUC) measurements. Increases in ACh levels above the baseline release, i.e., percentage change from baseline data starting from the time of the first injection (−20 min or zero min) until the levels reached the pre-injection basal release, were used in the calculation of AUC using the trapezoidal rule (Graph Pad Prizm). The baseline is defined as the average release in three fractions (20 min each) prior to the first injection and this was equated to 100%. The differences in AUC values following various pharmacological challenges were assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by appropriate post hoc analysis (Dunnett's or Neuman-Keul's tests).

Results

Systemic administration of nicotine and antagonists

Three to four hours following the implantation of the dialysis probes, hippocampal ACh release reached a stable baseline. The basal ACh release under these conditions appeared to have a synaptic origin as evidenced by a marked attenuation of the basal release by the inclusion of tetrodotoxin (1 μM) or the removal of extracellular calcium from the aCSF (>99% attenuation in both cases, data not shown).

Under the conditions employed, the average basal level of ACh in the hippocampal dialysates was 187±26 fmoles per 20 min (mean±s.e.mean, n=19). Subcutaneous administration of saline (1 ml kg−1) caused a transient increase in the ACh levels in hippocampal dialysates (F(1,10)=7.4, P<0.01; Figure 1) and this increase lasted for up to 20 min (P<0.05 vs pre-treatment basal release, Dunnett's test). In preliminary studies, nicotine (0.2, 0.4 and 0.7 mg kg−1, s.c.) showed a bell-shaped dose response relationship at increasing hippocampal ACh release (data not shown). Nicotine (0.4 mg kg−1, s.c.) induced a reliable and statistically significant increase in the levels of ACh in hippocampal dialysates versus saline control (F[12,81]=2.5, P=0.0077). The peak increase (i.e., maximum statistically significant effect) of 213% of baseline was observed at 40 min post-injection, and the increase in ACh levels persisted for at least 120 min post-injection (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of saline and nicotine (NIC) on ACh levels in hippocampal dialysates. Nicotine (0.4 mg kg−1, n=5) or saline (n=4) was administered subcutaneously at time=0 and the ACh levels in the dialysates determined as described in Methods. The data represent the mean±s.e.mean of the groups. +P<0.05 vs pretreatment baseline (saline; one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test), *P<0.05 for the effect of nicotine vs the saline control (two-way ANOVA). The arrow indicates the time of injection (zero min).

For experiments designed to test the pharmacological sensitivity of nicotine (0.4 mg kg−1, s.c.)-induced hippocampal ACh release, antagonists were given 20 min prior to s.c. injection of nicotine. Control groups of animals received two injections of saline and this resulted in a modest increase in hippocampal ACh levels (F(1,12)=2.35, P=0.0252) as compared to pre-injection baseline. However, post hoc analysis did not indicate significant differences between the pre-injection baseline and ACh release from 0–120 min post-injection. Injection of nicotine (0.4 mg kg−1, s.c.) following a saline injection resulted in a statistically significant increase in ACh levels (Figure 2). Pretreatment with the noncompetitive nAChR antagonist mecamylamine (3.0 mg kg−1, s.c.), attenuated the effect of systemic nicotine administration (F[14,19]=2.36, P=0.005; Figure 2). The increase in ACh levels in hippocampal dialysates induced by mecamylamine alone (3.0 mg kg−1, s.c.) was not different from a saline injection (data not shown).

Figure 2.

The pharmacology of nicotine (NIC)-induced hippocampal ACh release. Rats were given saline or various antagonists 20 min prior to s.c. injection of nicotine (0.4 mg kg−1) or saline. Arrows (−20 and zero min) denote the injection times. Values represent mean±s.e.mean (n=6–7; saline+saline, n=7; saline+nicotine, n=6; mecamyalime (MEC; 3.0 mg kg−1)+nicotine, n=6; DHβE (3.0 mg kg−1)+nicotine, n=7; SCH-23390 (0.3 mg kg−1)+nicotine, n=6). *P<0.05 for the effect of saline/nicotine vs the saline/saline response (two-way ANOVA); +P<0.05 for the effect of antagonist/nicotine vs the saline/nicotine response (two-way ANOVA).

The pretreatment with the competitive nAChR antagonist DHβE (4 mg kg−1, s.c.), also antagonized the ACh release induced by nicotine (0.4 mg kg−1; F[14,160]=3.16, P=0.0002; Figure 2). DHβE, when administered alone, caused an increase in ACh levels; however, this increase was not statistically different from a saline injection (data not shown).

In addition to the attenuating effects of the nAChR antagonists, the dopamine D1 receptor antagonist SCH-23390 (0.3 mg kg−1, s.c.), also attenuated the effect of systemic nicotine administration (Figure 2, F[14,148]=4.28, P<0.0001). SCH-23390 administered alone did not alter the basal ACh release and in addition, the injection of SCH-23390 did not elicit a transient increase in ACh release normally seen with saline injection (data not shown).

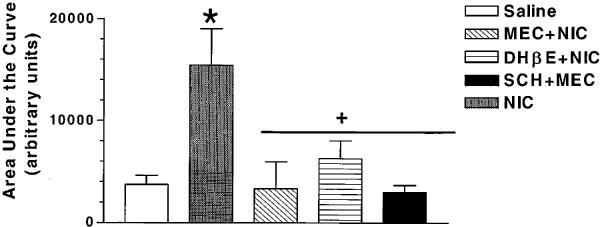

The area under the curve estimates of ACh release (Figure 3) shows a similar profile. Nicotine injection produced significant increase in AUC over saline injection and this was significantly reversed by all three antagonists examined (F(4,19)=5.25, P=0.0051). The post hoc Neuman-Keul's test indicated no significant differences among the three antagonists in their abilities to attenuate NIC-induced ACh release. In addition, there were no differences in AUC values obtained by saline+saline treatment vs antagonist+NIC injection (P>0.05).

Figure 3.

Summary of effects of mecamylamine (MEC), DHβE or SCH-23390 on nicotine (NIC)-induced ACh release from rat hippocampus. The area under curve values were determined using the trapezoidal rule and the values represent arbitrary units (mean±s.e.mean, n=6–7). *P<0.05 vs saline+saline response, +P<0.05 vs saline+nicotine response (ANOVA followed by Neuman-Keul's test).

Systemic administration of nicotine with local perfusion of antagonists

To characterize the site and the mechanism of nicotine-induced hippocampal ACh release, MEC, DHβE or SCH-23390 were perfused locally, while nicotine (0.4 mg kg−1) was given by s.c. injection. The perfusion of the antagonists was initiated 20 min before the s.c. injection of nicotine and continued for up to 200 min. Initial studies were conducted to determine the optimum concentration for the antagonists for these studies. Mecamyaline and DHβE, each at 100 μM concentration, and SCH-23390 at 10 μM concentration did not affect the basal ACh release from hippocampus (Figure 4). Higher concentrations of either mecamylamine (1 mM) or SCH-23390 (100 μM) per se increased the levels of ACh in the perfusates (data not shown). Direct perfusion of mecamylamine (100 μM) did not significantly attenuate the nicotine-induced ACh increase in the dialysis perfusates (F(15,126)=1.49, P=0.11; Figure 4). Similarly direct perfusion of DHβE (100 μM) also did not attenuate nicotine's effect (F(11,72)=1.69, P=0.093). Although ACh levels at 100, 120 and 140 min following s.c. injection of nicotine with a local perfusion of DHβE (100 μM) appeared to be lower than those seen with nicotine alone, two-way ANOVA did not reveal any overall significant differences between the time course profiles of nicotine alone vs nicotine+DHβE (F(11,72)=1.69, P>0.05). In contrast, local perfusion of SCH-23390 (10 μM) significantly inhibited the effect of subcutaneous nicotine administration on hippocampal ACh release (F(14,148)=4,28, P<0.0001; Figure 4). The area under the curve measurements further support these observations (Figure 5; F[4,20]=6.4, P<0.01). Post hoc Dunnett's test indicated significant effect of SCH-23390 (P<0.05), but not of MEC or DHβE.

Figure 4.

Effects of local perfusion of various antagonists on increases in ACh levels in hippocampal dialysates induced by s.c. injection of nicotine (NIC, 0.4 mg kg−1). The perfusion of antagonists mecamylamine (MEC, 100 μM, n=5), DHβE (100 μM, n=4) or SCH-23390 (10 μM, n=4)) was initiated 20 min before the s.c. injection of nicotine (n=5). The arrows indicate the times of injection (−20 and zero min). Values represent mean±s.e.mean, n=5–6). *P<0.05 antagonist+nicotine vs nicotine+aCSF response. The horizontal line indicates the duration of perfusion and the arrows indicate the initiation and termination of the perfusion.

Figure 5.

Summary of the effects of local perfusion of mecamylamine (MEC), DHβE or SCH-23390 on nicotine (NIC, 0.4 mg kg−1, s.c.)-induced hippocampal ACh release. The area under curve values expressed as arbitrary units (mean±s.e.mean, n=5–6) were determined using the trapezoidal rule. *P<0.05 vs saline+aCSF response, +P<0.05 vs nicotine+aCSF response.

Local perfusion of nicotine and antagonists

To determine if the effect of nicotine on hippocampal ACh release is mediated via nAChRs within the hippocampus, nicotine was perfused into the sampling area via the microdialysis probe. Nicotine at a concentration of 1 mM in the perfusion solution increased levels of ACh in the hippocampal perfusate (F(1,10)=9, P<0.05) with a peak increase of 180±17% of baseline (mean±s.e.mean; Figure 6). Significant increases in ACh levels were noted soon after the initiation of the perfusion (i.e., 20 min), persisted throughout the perfusion and returned to baseline levels soon after the removal of nicotine from the aCSF. The ACh levels decreased to baseline soon after the removal of nicotine from the aCSF; however, these changes were not statistically significant (post hoc Neuman-Keul's test). Nicotine at a lower concentration (100 μM) failed to cause an increase in ACh levels in the perfusate (data not shown). The effects of the antagonists on the nicotine-induced increases in ACh levels from the hippocampal perfusates were examined by co-perfusion of MEC (100 μM) or SCH-23390 (10 μM) with nicotine (1 mM). Neither of the antagonists had any significant effect on nicotine induced increase in ACh levels in the dialysates (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The effects of local perfusion of various antagonists on ACh release elicited by local perfusion of nicotine (NIC, 1 mM, n=7). The antagonists mecamylamine (MEC, 100 μM, n=5), or SCH-23390 (10 μM, n=4) were co-perfused with nicotine in aCSF. Values represent mean±s.e.mean. The horizontal line denotes the duration of perfusion and the arrows indicate the initiation and termination of perfusion.

Discussion

In recent years, the beneficial effects of nicotine on attention, learning and memory have been reported (Levin, 1992; Wilson et al., 1995). Despite the putative role of ACh in cognitive processes the effects of nicotine on cholinergic systems has received little attention. The aim of the present study was to understand the mechanism by which nicotine increases hippocampal levels of ACh in vivo.

In the present study, we demonstrated nicotine-induced hippocampal ACh release in vivo following subcutaneous injection. These results are consistent with those reported by Toide & Arima (1989) and Tani et al. (1998). Further, we extended these studies by demonstrating the sensitivity of nicotine-evoked hippocampal ACh to subcutaneously administered MEC and DHβE, two antagonists of nAChRs. These results unequivocally implicate nAChRs in this response. These observations also support similar conclusions by Tani et al. (1998). Alpha-bungarotoxin-sensitive nAChRs are another potential target for nicotine's actions. However, this subtype does not appear to be involved in nicotine-induced ACh release in the hippocampus as evidenced by a lack of effect of a selective alpha-bungarotoxin-sensitive nAChR antagonist, methyllycaconitine on nicotine-induced hippocampal ACh release and by a lack of effect of 3(2,4-dimethoxybenzlidine)-anabaseine (GTS-21), a ligand known to have agonist activity at the alpha-bungatotoxin-sensitive nAChRs (De Fiebre et al., 1995), on hippocampal ACh release (Tani et al., 1998).

Since nicotine is known to release DA within the hippocampus (Brazell et al., 1991) which in turn can increase ACh release, we hypothesized that nicotine-evoked DA release may contribute, in part, to the hippocampal ACh release. The sensitivity of nicotine-evoked ACh release to subcutaneously injected SCH-23390 clearly supports this hypothesis. SCH-23390 (10 μM), which attenuated the nicotine-induced ACh release, did not affect basal ACh release suggesting a lack of tonic regulation of ACh release by D1 receptors. Therefore, SCH-23390 is unlikely to attenuate nicotine-induced ACh release by a tonic-inhibitory mechanism. SCH-23390 at higher concentrations (100 μM) per se increased ACh release, and this may be unrelated to its D1 receptor antagonism as SCH-23390 is known to interact with other receptors such as the serotonergic receptors at higher concentrations (McQuade et al., 1988). Interestingly, the magnitude of the attenuation by SCH-23390 of nicotine-evoked ACh release was similar to that seen with nAChR antagonists, MEC or DHβE suggesting that the DA release and DA (D1) receptor activation are critical events in the nAChR-mediated ACh release in vivo.

Increases in hippocampal ACh levels following the systemic injection of nicotine might result from the activation of nAChRs within or outside the hipocampus. To elucidate the site of action of nicotine, two sets of studies were conducted: (1) subcutaneous injection of nicotine preceded by local perfusion of nAChR antagonists and D1 antagonist; and (2) co-perfusion of selected antagonists along with nicotine through a microdialysis probe into the hippocampus. For both of these experimental conditions, we used concentrations of antagonists that were devoid of intrinsic effects on hippocampal ACh release. Pretreatment with SCH-23390 (10 μM) attenuated hippocampal ACh release response due to systemic nicotine administration while the putative nAChR antagonists, MEC and DHβE were ineffective, each applied at a concentration of 100 μM. The possibility that the nicotinic antagonists were applied at concentrations below their minimum effective concentrations to block nAChRs and/or that the antagonists did not diffuse sufficiently across the dialysis membranes exists. Nissel et al. (1994a) and Marshall et al. (1997) have shown that perfusion of MEC (100 μM) through microdialysis probes attenuates DA release in nucleus accumbens or striatum elicited by a systemic injection or local perfusion of nicotine. Mitchell (1993) demonstrated that MEC (25 μM) perfused into the hippocampus via a microdialysis probe attenuated NE release in the hippocampus elicited by co-perfusion of nicotine. These data suggest that the concentrations employed in the present investigation are in the effective concentration range known to antagonize nicotine-evoked neurotransmitter release in vivo using microdialysis techniques. At higher concentrations (>100 μM), MEC per se increased ACh release. Similarly, Nissel et al. (1994a) also observed increases in DA release in the rat nucleus accumbens with a perfusion of MEC (1 mM). Therefore, the sensitivity of nicotine-evoked ACh release to higher concentrations of MEC could not be examined unequivocally. The relative lack of effect of nAChR antagonists on ACh release evoked by a systemic injection of nicotine, tend to suggest that nicotine's site of action lies outside of the hippocampus. The sensitivity of hippocampal ACh release evoked by a systemic injection of nicotine to SCH-23390 suggests that hippocampal ACh release evoked systemic nicotine requires local DA release and D1 receptor activation.

To delineate if hippocampal nAChRs are involved in nicotine-induced ACh release in vivo, nicotine (1000 μM) was directly perfused with or without MEC (100 μM) or SCH-23390 (10 μM). Local perfusion of nicotine at 1 mM concentration, but not 0.1 mM, increased hippocampal ACh levels. Marshall et al. (1997) and Nissel et al. (1994a,1994b) have reported nicotine-evoked increases in DA levels in striatum, nucleus accumbens or frontal cortex in the similar concentration range. Increases in hippocampal ACh release following direct perfusion of nicotine suggest a local action within the hippocampus. However, the pharmacology of ACh release evoked by direct perfusion of nicotine appears to be different from that seen with systemic administration in that the response was insensitive to co-perfusion of MEC (100 μM) or SCH-23390 (10 μM). A higher concentration of SCH-23390 (100 μM) per se increased hippocampal ACh release, hence this concentration could not be used in the antagonism experiments. However, it must be noted that the concentration of SCH-23390 (10 μM), used in these experiments, was fully efficacious at attenuating ACh release elicited by the systemic injection of nicotine (see above and Figure 4). Therefore, the results from the local perfusion experiments suggest that nicotine can elicit ACh release within the hippocampus through a non-dopaminergic mechanism. In addition, the relative lack of effect of nAChR antagonists argues against the involvement of nAChRs. In microdialysis experiments, nicotine-induced DA release that is insensitive to co-perfused MEC was observed in rat striatum, nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex (Marshall et al., 1997) and this phenomenon appeared to be dependent on the concentration of nicotine used. In addition, regional differences in MEC sensitivity were noted in that nicotine-evoked DA release in the striatum and nucleus accumbens showed a greater MEC sensitivity than DA release in the prefrontal cortex. Recently, Fu et al. (1999) reported nicotine-induced hippocampal NE release that is insensitive to local perfusion of MEC or DHβE (Fu et al., 1999). Additional studies are needed to delineate the pharmacology of the nicotine-induced neurotransmitter release that is insensitive to putative nAChR antagonists.

Taken together, the systemic and local administration studies suggest that nicotine-induced hippocampal ACh release involves two distinct mechanisms, one that involves an extra-hippocampal site of nAChR activation leading to hippocampal DA release and subsequent D1 receptor activation, the second mechanism that involves non-DA-ergic mechanism. Nicotine-induced hippocampal norepinephrine release in vivo is also known involve an extra-hippocampal site, presumably the noradrenergic cell bodies originating from the locus coereleus (Mitchell, 1993).

Since the hippocampal formation receives its DA-ergic inputs from the VTA (Bischoff et al., 1979; Scatton et al., 1980), the nicotine-induced hippocampal ACh release may be mediated, in part, via the activation of nAChRs located in the VTA. Dopaminergic (D1 receptor) regulation of hippocampal ACh release is established from anatomical and functional studies as summarized below. Hippocampal D1 receptors have been localized to the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus and the dorsal hippocampus (Dawson et al., 1986; Grilli et al., 1988; Tiberi et al., 1991). Significant loss of hippocampal D1 receptors with a concomitant loss of choline acetyltransferase activity (ChAT) after fimbriaectomy (Hersi et al., 1995) suggests that a subpopulation of the D1 receptors are presynaptically localized on the cholinergic afferents. Direct perfusion of SKF-38393, a selective D1 receptor agonist, into the hippocampus, but not septum, has been shown to increase ACh levels (Hersi et al., 1995). Brazell et al. (1991) reported that nicotine at behaviourally active doses (0.2–0.8 mg kg−1, s.c.) increases both NE and DA in the rat hippocampus. These observations, taken together, further support the involvement of nAChR activation of VTA-hippocampal DA-ergic pathway, DA release, D1 receptor activation in nicotine-induced hippocampal ACh release in vivo.

In summary, in the present investigation, we have demonstrated a unique pharmacology for nicotine-induced hippocampal ACh release. The effect of nicotine is both intra- and extra-hippocampal, with the latter apparently having predominance after systemic administration of nicotine. A possible mechanism is via activation of nAChRs located on the DA soma in the VTA resulting in hippocampal DA release and subsequent activation of D1 receptors, culminating in the release of ACh within the hippocampus thus involving a permissive DA synapse.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lucia Correa, Michael Keegan and Emily Santori for their excellent technical assistance. The authors acknowledge discussions with Dr H.C. Fibiger during the course of the investigation. Preliminary results of this work have been presented in an abstract form. Proceedings of the 7th international conference on in vivo methods. Tenerife, Spain (1996). pp 162–163.

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- DA

dopamine

- DHβE

dihydro-β-erythrodine

- nAChR

neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- SCH-23390

R-(+)-7-chloro-8-hydroxy-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-benzazepine

References

- ARAUJO D.M., LAPCHACK P.A., COLLIER B., QUIRION R. Characterization of N-[3H]methylcarbamylcholine binding sites and effect on N-methylcarbamylcholine on acetylcholine release in rat brain. J. Neurochem. 1988;51:292–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb04869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARTUS R.T., DEAN R.L., BEER B., LIPPA A.S. The cholinergic hypothesis of geriatric memory dysfunction. Science. 1982;217:408–417. doi: 10.1126/science.7046051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEANI L., BIANCHI C., NILSSON L., NORDBERG A., ROMANELLI L., SIVILOTTI L. The effects of nicotine and cytisine on [3H]acetylcholine release from cortical slices of guinea-pig brain. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1985;331:293–296. doi: 10.1007/BF00634252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BISCHOFF S., SCATTON B., KORF J. Biochemical evidence for neurotransmitter role of dopamine in the rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 1979;165:161–165. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRAZELL M.P., MITCHELL S.N., GRAY J.A. Effect of acute administration of nicotine on in vivo release of noradrenaline in the hippocampus of freely moving rats: a dose-response and antagonist study. Neuropharmacology. 1991;30:823–833. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(91)90116-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUCCAFUSCO J.J., JACKSON W.J. Beneficial effects of nicotine administered prior to delayed matching to sample task in the young and aged monkeys. Neurobiol. Aging. 1991;12:233–238. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(91)90102-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLARKE P.B.S., RUBEN M. Release of [3H]-noradrenaline from rat hippocampal synaptosomes by nicotine : mediation by different nicotinic receptor subtypes from striatal [3H]-dopamine release. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:595–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15232.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAWSON T.M., GEHLERT D.R., MCCABE R.T., BARNETT A., WAMSLEY J.K. D1 dopamine receptors in the rat brain: a quantitative autoradiographic analysis. J. Neurosci. 1986;6:2352–2365. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-08-02352.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAY J.C., FIBIGER H.C. Dopaminergic regulation of septohippocampal cholinergic neurons. J. Neurochem. 1994;63:2086–2092. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63062086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAZZI L., MOTZO C., IMPERATO A., SERRA M., GESSA G.L., BIGGIO G. Modulation of basal and stress induced release of acetylcholine and dopamine rat brain by abecarnil and imidazenil, two anxioselective γ-aminobutyric acidA receptor modulators. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;273:241–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEFIEBRE C.M., MEYER E.M., HENRY J.C., MURASKIN S.I., KEM W.R., PAPKE R.L. Characterization of a series of anabaseine-derived compounds reveals that 3-(4)-dimethylaminocinnamylidine derivative is a selective agonist at neuronal nicotinic α7/125-I-α-bungatoxin subtypes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;47:164–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DURKIN T., GALEY D., MICHEAU J., BESLON H., JAFFARD R. The effects of intraseptal injection of haloperidol in vivo on hippocampal cholinergic function in the mouse. Brain Res. 1986;376:420–424. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FU Y., MATTA S.G., SHARP B.M. Local a-bungarotoxin-sensitive nicotinic receptors modulate hippocampal norepinephrine release by systemic nicotine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;289:133–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRILLI M., NISOLI E., MEMO M., MISSALE C., SPANO P. Pharmacological characterization of D1 and D2 dopamine receptors in rat limbocortical areas II: dorsal hippocampus. Neurosci. Lett. 1988;87:253–258. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90457-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERSI A.I., RICHARD J.W., GAUDREAU P., QUIRION R. Local modulation of hippocampal acetylcholine release by dopamine D1 receptors: A combined receptor autoradiography and in vivo dialysis study. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:7150–7157. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07150.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IMPERATO A., MULAS A., DI CHIARA G. Nicotine preferentially stimulates dopamine release in the limbic system of freely moving rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1986;132:337–338. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90629-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IMPERATO A., OBINU C.M., DI CHIARA G. Stimulation of both dopamine D1 and D2 receptors facilitates in vivo acetylcholine release in the hippocampus. Brain Res. 1993;618:341–345. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IZUMU J., WASHIZUKA M., MIURA N., HIRAGA Y., IKEDA Y. Hippocampal serotonin 5-HT1A receptor enhances acetylcholine release in conscious rats. J. Neurochem. 1994;62:1804–1808. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62051804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVIN E.D. Nicotinic systems and cognitive function. Psychopharmacology. 1992;108:417–431. doi: 10.1007/BF02247415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARSHALL D.L., REDFERN P.H., WONNACOTT S. Presynaptic nicotinic modulation of dopamine release in the three ascending pathways studied by in vivo microdialysis: comparison of naïve and chronic nicotine treated rats. J. Neurochem. 1997;68:1511–1519. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68041511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCQUADE R.D., FORD D., DUFFY R.A., CHIPKIN R.E., IORIO L.C., BARNETT A. Serotonergic component of SCH23390: in vitro and in vivo binding analyses. Life Sci. 1988;43:1861–1869. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(88)80003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEYER E.M., ARENDASH G.W., JUDKINS J.H., YING L., WADE C., KEM W.R. Effects of nucleus basalis lesions on the muscarinic and nicotinic modulation of [3H]acetylcholine release in the rat cortex. J. Neurochem. 1987;49:1758–1762. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb02433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIFSUD J.C., HERNANDEZ L., HOBEL B.G. Nicotine infused into the nucleus accumbens increases synaptic dopamine as measured by in vivo microdialysis. Brain Res. 1989;478:365–367. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91518-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MITCHELL S.N. Role of the locus coeruleus in the noradrenergic response to a systemic administration of nicotine. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32:937–949. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90058-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOCHIZIUKI T., OKAKURA-MOCHIZUKI K., HORII A., YAMAMOTO Y., YAMATODANI A. Histaminergic modulation of hippocampal acetylcholine release in vivo. J. Neurochem. 1994;62:2275–2282. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62062275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOGHADDAM B., BUNNEY B.S. Ionic composition of microdialysis perfusing solution alters the pharmacological responsiveness and basal outflow of striatal dopamine. J. Neurochem. 1989;53:652–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb07383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NISELL M., NOMIKOS G.G., SVENSSON T.H. Systemic nicotine-induced dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens is regulated by nicotinic receptors in the ventral tegmental area. Synapse. 1994a;16:36–44. doi: 10.1002/syn.890160105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NISELL M., NOMIKOS G.G., SVENSON T.H. Infusion of nicotine in the ventral tegmental area or nucleus accumbens of the rat differentially affects accumbal dopamine release. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1994b;75:348–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1994.tb00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NORDBERG A., ROMANELLI L., SUNDWALL A., BIANCHI C., BEANI L. Effect of acute and chronic nicotine treatment on cortical acetylcholine release and on nicotinic receptors in rats and guinea pigs. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1989;98:71–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb16864.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAXINOS G., WATSON C. The Rat Brain is Stereotaxic Coordinates 1986Academic Press: London; 2nd edn [Google Scholar]

- PERRY E.K., TOMLINSON B.E., BLESSED G., BERGMANN K., GIBSON P.H., PERRY R.H. Correlation of cholinergic abnormalities with senile plaques and mental test scores in senile dementia. Br. Med. J. 1978;2:1457–1459. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6150.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUIRION R., RICHARD J., WILSON A. Muscarinic and nicotinic modulation of cortical acetylcholine release monitored by in vivo microdialysis in freely moving adult rats. Synapse. 1994;17:92–100. doi: 10.1002/syn.890170205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBINSON S.E., MALTHE-SORRENSON D., WOOD P.L., COMMINIONG J. Dopaminergic control of the septal-hippocampal pathway. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1979;208:476–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROWELL P.P., WINKLER D.L. Nicotinic stimulation of [3H]acetylcholine release from mouse cerebral cortical synaptosomes. J. Neurochem. 1984;43:1593–1598. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb06083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SACCAN A.I., DUNLOP J.L., LLOYD G.K. Pharmacological characterization of neuronal acetylcholine gated ion channel-receptor mediated hippocampal norepinephrine and striatal dopamine release from rat brain slices. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;274:224–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCATTON B., SIMON H., LE MOAL M., BISCHOFF S. Origin of dopaminergic innervation of the rat hippocampal formation. Neurosci. Lett. 1980;18:125–131. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(80)90314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUMMERS K.L., CUADRA G., NARITOKU D., GIACOBINI E. Effects of nicotine on levels of acetylcholine and biogenic amines in rat cortex. Drug Dev. Res. 1994;31:108–119. [Google Scholar]

- SUMMERS K.L., KEM W.R., GIACOBINI E. Nicotinic agonist modulation of neurotransmitter levels in the rat prefrontal cortex. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1997;74:139–146. doi: 10.1254/jjp.74.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANI Y., SAITO K., IMOTO M., OHNO T. Pharmacological characterization of nicotinic receptor-mediated acetylcholine release in the rat brain: an in vivo microdialysis study. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;351:181–188. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TIBERI M., JARVIE K.R., SILVIA C., FALARDEAU P., GINGRICH J.A., GODINOT N., BERTRAND L., YANG-FENG T.L., FREMEAU R.T., CARON M.G. Cloning, molecular characterization and chromosomal assignment of a gene encoding a second D1 dopamine receptor subtype: differential expression pattern in rat brain compared with the D1A subtype. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:7491–7495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOIDE K., ARIMA T. Effects of cholinergic drugs on extracellular levels of acetylcholine and choline in rat cortex, hippocampus and striatum studied by brain dialysis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1989;173:133–141. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90510-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERNEY C., BAULAC M., BERGER B., ALVAREZ C. Morphological evidence for a dopaminergic terminal field in the hippocampal formation of young and adult rat. Neuroscience. 1985;14:1039–1052. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90275-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILCOCK G.K., ESIRI M.M., BOWEN D.M., SMITH C.C. Alzheimer's disease: correlation of cortical choline acetyltransferase activity with the severity of dementia and histological abnormalities. J. Neurol. Sci. 1982;57:407–417. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(82)90045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILKIE G.I., HUTSON P.H., STEPHENS M.W., WHITING P., WONNACOTT S. Hippocampal nicotinic autoreceptors modulate acetylcholine release. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1993;21:429–431. doi: 10.1042/bst0210429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILKIE G.I., HUTSON P., SULLIVAN J.P., WONNACOTT S. Pharmacological characterization of a nicotinic autoreceptor in rat hippocampal synaptosomes. Neurochem. Res. 1996;21:1141–1148. doi: 10.1007/BF02532425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILSON A.L., LANGLEY L.K., MONLEY J., BAUER T., ROTTUNDA S., MCFALLS E., KOVERA C., MCCARTEN J.R. Nicotine Patches in Alzheimer's disease: pilot study on learning, memory and safety. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1995;51:509–514. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)00043-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WONNACOTT S. Presynaptic nicotinic ACh receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:92–98. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOOD P.L. Pharmacological evaluation of GABAergic and glutaminergic inputs into the nucleus basalis-cortical and septohippocampal cholinergic projections. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1985;64:325–328. doi: 10.1139/y86-053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]