Abstract

Recent evidence indicates that sildenafil may exert some central effects through enhancement of nitric oxide (NO)-mediated effects. NO is known to have modulatory effects on seizure threshold, raising the possibility that sildenafil may alter seizure susceptibility through NO-mediated mechanisms. This study was performed to examine whether sildenafil influences the threshold of clonic and/or generalized tonic seizures through modulation of nitric oxide (NO)–cGMP pathway.

The effect of sildenafil (1–40 mg kg−1) was investigated on clonic seizures induced by intravenous administration of GABA antagonists pentylenetetrazole (PTZ) and bicuculine and on generalized tonic seizures induced by intraperitoneal administration of high dose PTZ in male Swiss mice. The interaction of sildenafil-induced effects with NO–cGMP pathway was examined using nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor, N(G)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), NOS substrate L-arginine, NO donor, sodium nitroprusside (SNP) and guanylyl cyclase inhibitor methylene blue (MB).

Sildenafil induced a dose-dependent proconvulsant effect in both models of clonic, but not generalized tonic type of seizures. Pretreatment with either MB or L-NAME inhibited the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil, indicating the mediation of this effect by NO–cGMP pathway. In addition, a subeffective dose of sildenafil induced an additive proconvulsant effect when combined with either L-arginine or SNP.

Sildenafil induces a proconvulsant effect on clonic seizure threshold that interacts with both exogenously and endogenously released NO and may be linked to activation of NO–cGMP pathway.

Keywords: Sildenafil, clonic seizure threshold, pentylenetetrazole, bicuculine, nitric oxide, L-NAME, L-arginine, sodium nitroprusside, mice

Introduction

Sildenafil citrate is a drug widely used for male erectile dysfunction. It is a selective phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitor that enhances the effect of nitric oxide (NO) in the target tissues by inhibiting the cGMP degradation (Boolell et al., 1996; Jackson et al., 1999; Leung & Yip, 1999). In the corpus cavernosum, this increase in cGMP leads to the relaxation of the smooth muscle and with an increase in blood flow into the penis, it helps to alleviate erectile problems (Boolell et al., 1996; Jackson et al., 1999; Moreira et al., 2000). Sildenafil is shown to have no effect on the penis in the absence of sexual stimulation, when the concentrations of NO and cGMP are low (Moreira et al., 2000; Boyce & Umland, 2001).

Several direct effects of sildenafil administration on the CNS have been reported in both humans and rodents. These effects in human include dizziness, depression, insomnia, abnormal dreams and nervousness (Moreira et al., 2000; Milman & Arnold, 2002). Also recreational sildenafil use and its association with men's substance abuse behaviors have been reported (Crosby & Diclemente, 2004). Recent evidence from experimental animals suggest that activation of NO–cGMP pathway by sildenafil may lead to central effects including modulation of pain perception and anxiety behaviors (Mixcoatl-Zecuatl et al., 2000; Asomoza-Espinosa et al., 2001; Jain et al., 2001; Prickaerts et al., 2002; Volke et al., 2003; Kurt et al., 2004).

NO is a gaseous free radical, which is synthesized from the amino-acid L-arginine by nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and functions as a neuronal messenger and as a modulator of neurotransmitters in the brain (Moncada et al., 1991). NO is a potent stimulator of guanylyl cyclase, resulting in increased levels of cGMP (Snyder & Bredt, 1991). Several lines of evidence suggest NO as a modulator of seizure activity with diverse anticonvulsant (Starr & Starr, 1993; Theard et al., 1995; Tsuda et al., 1997) and proconvulsant (De Sarro et al., 1991; Osonoe et al., 1994; Van Leeuwen et al., 1995; Nidhi et al., 1999) effects based on the type of seizure, source of NO and other neurotransmitter systems involved. The important role of NO in modulation of seizure threshold raises the hypothesis that sildenafil may affect the seizure susceptibility through NO-dependent mechanisms. Interestingly, Gilad et al. (2002) have recently reported the occurrence of seizure attacks in two healthy men after using sildenafil.

The present study examined the possible effect of sildenafil on seizure susceptibility in three experimental models of seizure: (1) clonic seizures induced by intravenous administration of the GABA receptor antagonist pentylenetetrazole (PTZ) (2) clonic seizures induced by another GABA antagonist bicuculine and (3) generalized tonic seizures induced by intraperitoneal administration of a near maximal dose of PTZ (Löscher et al., 1991; Kupferberg, 2001). The induction of clonic seizures by intravenous infusion of PTZ represents a standard experimental model with both face and construct validity for petit-mal myoclonic seizure disorder (Swinyard & Kupferberg, 1985; Löscher et al., 1991). Intravenous bicuculine administration provides an alternative model for assessment of changes in clonic seizure threshold. In contrast to these two paradigms, generalized tonic-clonic seizures induced by near maximal intraperitoneal PTZ is a distinct model related to clinical grand-mal seizures (Löscher et al., 1991; Kupferberg, 2001). We also investigated the role of NO–cGMP pathway in the effect of sildenafil on seizure threshold by using NOS inhibitor, NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), NOS substrate L-arginine, NO donor, sodium nitroprusside (SNP) and guanylyl cyclase inhibitor methylene blue (MB).

Methods

Animals

Male Swiss mice weighing 24–33 g (Razi Institute, Karadj, Iran) were used in the study. The animals were housed in standard polycarbonate cages in a temperature-controlled room (24±2°C) with 12 h light/12 h dark cycle. Animals were acclimated at least 2 days before experiments with free access to food and water. The experiments were conducted between 09:00 and 15:00. All procedures were carried out in accordance with institutional guidelines for animal care and use and possible measures were undertaken to minimize the number of animals used and also to minimize animals' discomfort including immediate euthanasia after acute experiments. Groups consisted of five to seven animals and each animal was used only once.

Drugs

Sildenafil citrate (Vorin, India) was a generous gift from Poursina (Tehran, Iran). L-NAME, SNP, PTZ and bicuculine were purchased from Sigma (U.K.). L-arginine was purchased from Fluka (Switzerland). MB was a product of Hoechst (Germany). SNP was dissolved in distilled water. Other drugs were dissolved in saline solution. All drugs were injected to concentrations that the requisite doses were administered in a volume of 10 ml kg−1. Sildenafil citrate was injected subcutaneously; L-NAME, L-arginine and MB were injected intraperitoneally. Bicuculine was dissolved in warm 0.1 N HCL (0.2 mg ml−1), and the pH of the solution was adjusted to 5.5 with 1 N NaOH. PTZ was prepared in isotonic saline as 1% solution (10 mg ml−1) for intravenous injections (Swinyard & Kupferberg, 1985; Löscher et al., 1991) and as 850 mg 100−1 cm for intraperitoneal injections (Löscher & Lehmann, 1996; Homayoun et al., 2002a; Honar et al., 2004; Shafaroodi et al., 2004).

Seizure paradigms

Clonic seizure threshold

The clonic seizure threshold was determined by inserting a 30-gauge dental needle into the lateral tail vein of mouse (Löscher & Lehmann, 1996, Honar et al., 2004; Shafaroodi et al., 2004). The needle was then secured to the tail by a narrow piece of adhesive tape. With mouse moving freely, the PTZ solution or bicuculine solution was slowly infused into the tail vein at a constant rate of 0.5 ml min−1 using a Hamilton microsyringe, which was connected to the dental needle by polyethylene tubing. Infusion was halted when general clonus (forelimb clonus followed by full clonus of the body) was observed. Minimal dose of PTZ (mg kg−1 of mice weight) needed to induce general clonus was recorded as an index of clonic seizure threshold.

Generalized tonic seizure

In this model, PTZ (85 mg kg−1) was administered with a single intraperitoneal injection to evaluate the incidence and the latency for the onset of generalized tonic seizures and the incidence of death following seizures (Löscher & Lehmann, 1996; Homayoun et al., 2002a; Honar et al., 2004; Shafaroodi et al., 2004). The animals were observed for 30 min following PTZ injection.

Experiments

In experiment 1, animals received a subcutaneous injection of different doses of sildenafil citrate (1, 5, 10, 20 and 40 mg kg−1) 30 min before the determination of the threshold of clonic seizures induced by intravenous administration of PTZ solution. Control animals received the same volume of isotonic saline solution. The doses and time point were chosen according to pilot experiments and the study performed by Kurt et al. (2004). In experiment 2, sildenafil (10 mg kg−1) was administered to distinct groups of mice, 15, 30, 45 or 60 min before the determination of PTZ-induced clonic seizure threshold. Based on these two experiments, a dose of 10 mg kg−1 of sildenafil with a pretest injection interval of 30 min was used in subsequent experiments.

In experiment 3, animals received a subcutaneous injection of sildenafil (2.5, 5, 10 and 20 mg kg−1) or saline 30 min before the determination of bicuculine-induced clonic seizure threshold. To study the time-course of the effect of sildenafil on the bicuculine-induced seizure threshold, we performed experiment 4 in which sildenafil (20 mg kg−1, selected based on experiment 3) was injected 15, 30 and 45 min before bicuculine infusion to distinct groups of mice.

In experiments 5–10, we investigated the involvement of NO–cGMP pathway in the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil. In experiment 5, mice received intraperitoneal injections of either saline solution as controls or different doses of L-NAME (1, 5, 10 and 60 mg kg−1), MB (0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 1 and 2 mg kg−1), or L-Arginine (25, 50 and 100 mg kg−1), 45 min before measurement of PTZ-induced clonic seizure threshold. The doses were selected according to previous studies (Homayoun et al., 2002b, Kurt et al., 2004). According to the results of this experiment, the subthreshold doses of L-NAME (1 and 5 mg kg−1), MB (0.3, 0.5 and 1 mg kg−1), and L-arginine (25 and 50 mg kg−1) were chosen for the subsequent experiments.

In experiments 6 and 7, we studied the effect of pretreatment with L-NAME and MB, respectively, on the proconvulsant effect sildenafil in intravenous PTZ seizure paradigm. Experiments 8 and 9 were performed to study the effect of L-arginine and SNP on the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil. Experiment 10 tested the involvement of NO–cGMP pathway in the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil in intravenous bicuculine seizure paradigm. Table 1 represents the groups and injection protocols for the experiments 6–10. Drugs or vehicle were injected in separately grouped mice and seizure thresholds were measured 30 min after administration of the last treatment. The first injections in all these experiments were 15 min before second injection. The only exception was for the experiment 9, which was the combination treatment of SNP and sildenafil. In experiment 9, SNP (3 and 6 mg kg−1) was administered together with a subthreshold dose of sildenafil (5 mg kg−1). The dose of SNP was injected in two divided doses, one at the time of sildenfil injection and the other 15 min later. This procedure was used because of the short half-life of SNP and to lower the probability of death due to SNP as reported by others (Bujas-Bobanovic et al., 2000; Smith & Ogonowski 2003). Vehicle controls for this experiment were also injected by two doses of saline solution.

Table 1.

Groups and injection protocols for experiments 6–10

| First injection | Second injection | Seizure paradigm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 6 | Intravenous PTZ-induced clonic seizure threshold | ||

| Group 1 | Saline | Saline | |

| Group 2 | L-NAME 1 mg kg−1 | Saline | |

| Group 3 | L-NAME 5 mg kg−1 | Saline | |

| Group 4 | Saline | Sildenafil 10 mg kg−1 | |

| Group 5 | L-NAME 1 mg kg−1 | Sildenafil 10 mg kg−1 | |

| Group 6 | L-NAME 5 mg kg−1 | Sildenafil 10 mg kg−1 | |

| Experiment 7 | Intravenous PTZ-induced clonic seizure threshold | ||

| Group 1 | Saline | Saline | |

| Group 2 | MB 0.3 mg kg−1 | Saline | |

| Group 3 | MB 0.5 mg kg−1 | Saline | |

| Group 4 | MB 1 mg kg−1 | Saline | |

| Group 5 | Saline | Sildenafil 10 mg kg−1 | |

| Group 6 | MB 0.3 mg kg−1 | Sildenafil 10 mg kg−1 | |

| Group 7 | MB 0.5 mg kg−1 | Sildenafil 10 mg kg−1 | |

| Group 8 | MB 1 mg kg−1 | Sildenafil 10 mg kg−1 | |

| Experiment 8 | Intravenous PTZ-induced clonic seizure threshold | ||

| Group 1 | Saline | Saline | |

| Group 2 | L-Arginine 25 mg kg−1 | Saline | |

| Group 3 | L-Arginine 50 mg kg−1 | Saline | |

| Group 4 | Saline | Sildenafil 5 mg kg−1 | |

| Group 5 | L-Arginine 25 mg kg−1 | Sildenafil 5 mg kg−1 | |

| Group 6 | L-Arginine 50 mg kg−1 | Sildenafil 5 mg kg−1 | |

| Experiment 9 | Intravenous PTZ-induced clonic seizure threshold | ||

| Group 1 | Saline | Saline | |

| Group 2 | SNP 3 mg kg−1 | Saline | |

| Group 3 | SNP 6 mg kg−1 | Saline | |

| Group 4 | Saline | Sildenafil 5 mg kg−1 | |

| Group 5 | SNP 3 mg kg−1 | Sildenafil 5 mg kg−1 | |

| Group 6 | SNP 6 mg kg−1 | Sildenafil 5 mg kg−1 | |

| Experiment 10 | Intravenous bicuculine-induced clonic seizure threshold | ||

| Group 1 | Saline | Saline | |

| Group 2 | L-Arginine 50 mg kg−1 | Sildenafil 2.5 mg kg−1 | |

| Group 3 | Saline | Sildenafil 10 mg kg−1 | |

| Group 4 | MB 1 mg kg−1 | Sildenafil 10 mg kg−1 | |

| Group 5 | L-NAME 5 mg kg−1 | Sildenafil 10 mg kg−1 |

In experiment 11, we studied the effect of sildenafil (10 and 20 mg kg−1) on the rate and the latency of generalized tonic seizure and the rate of death induced by intraperitoneal administration of PTZ (85 mg kg−1). Sildenafil or vehicle was injected 30 min before PTZ.

Data analysis

Data of seizure thresholds are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) of clonic seizure thresholds in each experimental group. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc multiple comparisons were used to analyze the data where appropriate. In case of intraperitoneal PTZ paradigm, data of time latencies (seconds) for tonic seizures are expressed as medians (with 95% confidence intervals) and a nonparametric analysis based on median values (Kruskal–Wallis H test) was used for analysis. Incidences of tonic generalized seizures and death subsequent to intraperitoneal PTZ administration were compared between different groups using Pearson χ2 test. In all experiments, a P-value <0.05 was considered as the significance level between the groups.

Results

The effect of sildenafil on PTZ- or bicuculine-induced clonic seizure threshold

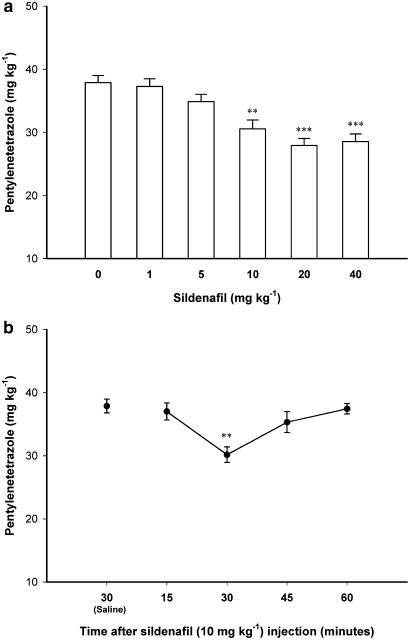

Figure 1a shows the effect of acute intraperitoneal administration of different doses of sildenafil (1, 5, 10, 20 and 40 mg kg−1) on PTZ-induced clonic seizure threshold. One-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect (F5, 30=13.218, P<0.001). Post hoc analysis showed a significant proconvulsant effect for sildenafil at doses of 10 and higher compared with saline-treated control animals. A dose of 10 mg kg−1 of sildenafil, which induced a significant proconvulsant effect, was chosen for further experiments to allow better detection of possible proconvulsant effects. Figure 1b shows the time-course of the proconvulsant effect of Sildenafil (10 mg kg−1). One-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect (F4, 22=6.912, P<0.01). Further post hoc analysis showed that sildenafil exerted a proconvulsant effect 30 min after administration (P<0.01, compared with saline-treated control group) and its effect vanished thereafter. The quick renormalization of seizure threshold may be related to fast pharmacokinetic of sildenafil in mice (Walker et al., 1999). In addition, the time course of effect of sildenafil is comparable to some other central effects of this drug (Jain et al., 2001; Araiza-Saldana et al., 2005).

Figure 1.

(a) The effect of different doses of sildenafil (0 (Saline), 1, 5, 10, 20 and 40 mg kg−1) on PTZ-induced clonic seizure threshold in mice. Sildenafil was injected subcutaneously 30 min before PTZ. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 compared with saline-treated control group. (b) The time-course of the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil (10 mg kg−1) on PTZ-induced clonic seizure threshold. Sildenafil was administered subcutaneously, 15, 30, 45 or 60 min before PTZ infusion. **P<0.01 compared with saline-treated group. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. Each group consisted of five to six animals.

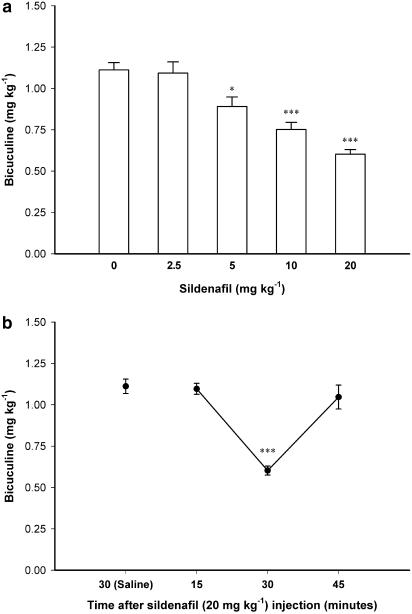

Figure 2a shows the effect of different doses of sildenafil (2.5, 5, 10 and 20 mg kg−1) on the threshold of bicucline-induced clonic seizures. One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc comparisons showed a proconvulsant effect for sildenafil in this model (F4, 24=20.463, P<0.001), which was significant with a dose of sildenafil as low as 5 mg kg−1 (P<0.05, compared with saline-treated control group). Figure 2b shows the time-course curve of the effect of sildenafil (20 mg kg−1) on the threshold of bicucline-induced clonic seizures. Analysis with one-way ANOVA (F3, 20=26.415, P<0.001) followed by Tukey's post hoc comparisons showed that the significant proconvulsant effect of sildenafil in bicucline-induced seizure model is observed at 30 min after sildenafil injection (P<0.001, compared with saline-treated controls) but not at 15 or 45 min which confirms the narrow time of action, already observed with PTZ.

Figure 2.

(a) The effect of different doses of sildenafil (0 (Saline), 2.5, 5, 10 and 20 mg kg−1) on the threshold of bicuculine-induced clonic seizures in mice. Sildenafil was injected subcutaneously, 30 min before bicuculine infusion. *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 in comparison with saline-treated control animals. (b) The time-course of the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil (20 mg kg−1) on the threshold of bicuculine-induced clonic seizures. Sildenafil was administered subcutaneously, 15, 30 or 45 min before bicuculine infusion. ***P<0.001 compared with saline-treated control group. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. Each group consisted of five to seven animals.

The effect of pretreatment with modulators of NO–cGMP pathway on the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil

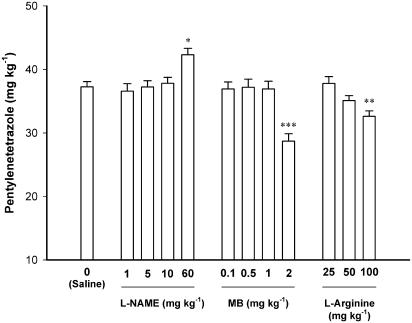

Figure 3 shows the effect of different doses of L-NAME (1, 5, 10 and 30 mg kg−1), MB (0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 1 and 2 mg kg−1), and L-arginine (25, 50 and 100 mg kg−1) on the threshold of PTZ-induced clonic seizure threshold. All the drugs were injected 45 minutes before PTZ-induced clonic seizure threshold determination. Comparison of the effect of different doses of L-NAME, MB, and L-Arginine with saline-treated controls using one-way ANOVA showed a significant qeffect for all these three agents [L-NAME (F4, 27=5.647, P<0.01), MB (F4, 24=11.406, P<0.001), and L-arginine (F3, 20=7.086, P<0.01)]. Post hoc comparisons showed that L-NAME with the highest dose used (60 mg kg−1) increased the threshold of clonic seizures when compared with saline-treated control animals (P<0.05). MB and L-arginine at the highest doses used (2 and 100 mg kg−1, respectively) decreased the PTZ-induced seizure threshold (P<0.001 and <0.01, respectively).

Figure 3.

Effects of L-NAME, MB, and L-arginine on the threshold of PTZ-induced clonic seizures in mice. All the drugs were injected 45 min before clonic seizure threshold examination. Controls animals received saline injections. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 compared with saline-treated animals. Each group consisted of five to seven mice.

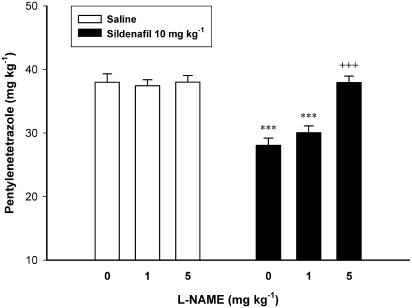

Figure 4 shows the effect of per se noneffective doses of L-NAME on the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil (10 mg kg−1). Two-way ANOVA with treatment 1 (L-NAME 1, 5 and 10 mg kg−1 or vehicle) as one factor and treatment 2 (sildenafil 10 mg kg−1 or vehicle) as second factor showed a significant effect for both treatment 1 (F2, 30=11.860, P<0.001) and treatment 2 (F1, 30=41.908, P<0.001), and a significant treatment 1 × treatment 2 interaction (F2, 30=10.933, P<0.001). Post hoc comparisons showed that L-NAME when administered before sildenafil dose-dependently inhibited the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil (P<0.001 in comparison with the group treated with saline before sildenafil).

Figure 4.

Effect of pretreatment with L-NAME on the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil in mice. L-NAME (0 (Saline), 1 or 5 mg kg−1) was injected 15 min before sildenafil (10 mg kg−1) or saline, which followed by PTZ-infusion 30 min later. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. ***P<0.001 compared with Saline/Saline group. +++P<0.001 compared with Saline/Sildenafil group. Each group consisted of five to seven mice.

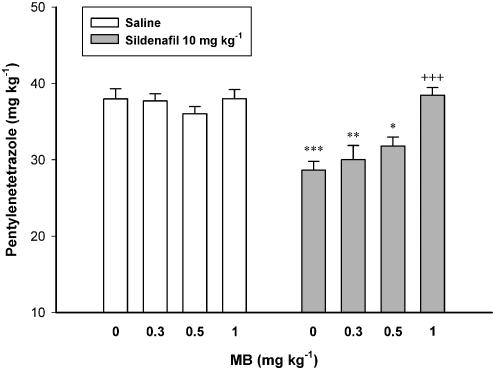

Figure 5 illustrates the effect of pretreatment with different subeffective doses of MB on the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil. Two-way ANOVA with treatment 1 (MB 0.3, 0.5 and 1 mg kg−1 or vehicle) as one factor and treatment 2 (sildenafil 10 mg kg−1 or vehicle) as second factor showed a significant effect for both treatment 1 (F3, 40=6.801, P<0.01) and treatment 2 (F1, 40=34.740, P<0.001), and a significant treatment 1 × treatment 2 interaction (F3, 40=6.153, P<0.01). Further analysis showed that MB dose-dependently inhibited the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil in intravenous PTZ seizure paradigm (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of MB on the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil in mice. MB (0 (Saline), 0.1, 0.3, 0.5 or 1 mg kg−1) was injected 15 min before sildenafil (10 mg kg−1) or saline, which followed by PTZ-infusion 30 min later. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 compared with Saline/Saline group. +++P<0.001 compared with Saline/Sildenafil group. Each group consisted of five to seven mice.

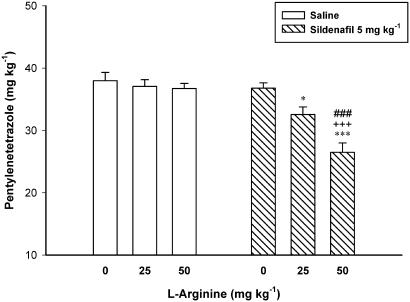

Figure 6 shows the effect of pretreatment with NO precursor L-arginine on the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil (5 mg kg−1). Two-way ANOVA with treatment 1 (L-arginine 25 and 50 mg kg−1 or vehicle) as one factor and treatment 2 (sildenafil 5, or vehicle) as second factor showed a significant effect for both treatment 1 (F2, 31=12.446, P<0.001) and treatment 2 (F1, 31=32.529, P<0.001), and a significant treatment 1 × treatment 2 interaction (F3, 31=7.776, P<0.01). Post hoc analysis showed that L-arginine with doses that did not affect seizure threshold was capable of inducing an additive/synergistic proconvulsant effect in combination with a subeffective 5 mg kg−1 dose of sildenafil.

Figure 6.

A subeffective dose of sildenafil induced an additive proconvulsant effect when combined with L-arginine. L-arginine (0 (Saline), 25 or 50 mg kg−1) was injected 15 min before sildenafil (5 mg kg−1) or saline, which followed by PTZ-infusion 30 min later. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 compared with Saline/Saline group, ###P<0.001 compared with L-arginine (50 mg kg−1)/Saline group, +++P<0.001 compared with Saline/Sildenafil group. Each group consisted of six to seven mice.

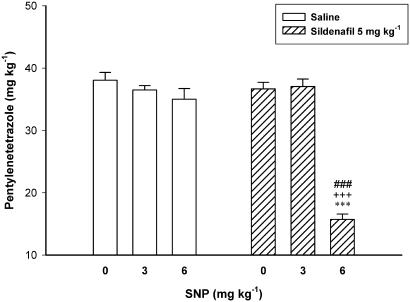

Figure 7 shows the effect of pretreatment with SNP on the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil. Two-way ANOVA with treatment 1 (SNP 0, 3 and 6 mg kg−1) as one factor and treatment 2 (sildenafil 0 and 5 mg kg−1) as second factor showed a significant effect for both treatment 1 (F2, 30=66.031, P<0.001) and treatment 2 (F1, 30=48.771, P<0.001), and a significant treatment 1 × treatment 2 interaction (F2, 30=43.248, P<0.01). Post hoc comparisons showed that SNP, which did not affect the seizure threshold at any doses by itself, caused a significant proconvulsant effect with dose of 6 mg kg−1 in combination with subthreshold 5 mg kg−1 dose of sildenafil (15.71±0.87 mg kg−1 vs 36.65±1.05 mg kg−1 for Saline/Sildenafil group, P<0.001). Two out of six animals treated with SNP (6 mg kg−1) plus sildenafil (5 mg kg−1) showed spontaneous myoclonic jerks before receiving PTZ in clonic seizure threshold exam. No deaths occurred in animals treated with SNP.

Figure 7.

Additive/synergistic proconvulsant effect of SNP and sildenafil in mice. SNP was injected in two divided doses, first of which together with sildenafil, 30 min before PTZ clonic seizure threshold examination and the rest 15 min later. Vehicle controls were also injected by two doses of saline solution. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. ***P<0.001 compared with Saline/Saline group. ###P<0.001 compared with SNP (6 mg kg−1)/Saline group. +++P<0.001 compared with Saline/Sildenafil group. Each group consisted of six to seven mice.

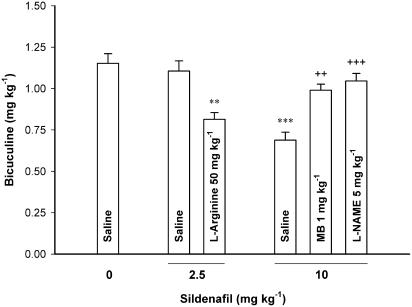

In bicuculine-induced seizure paradigm, the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil (10 mg kg−1) was blocked by pretreatment with L-NAME (5 mg kg−1) or MB (1 mg kg−1) (One-way ANOVA, F3, 22=16.246, P<0.001). The combination of the subeffective doses of L-arginine (50 mg kg−1) and sildenafil (2.5 mg kg−1) resulted in an additive/synergistic proconvulsant effect in bicuculine seizures (One-way ANOVA, F2, 18=11.331, P<0.01) (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

L-arginine potentiated while L-NAME or MB inhibited the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil in intravenous bicuculine seizure paradigm in mice. L-arginine (50 mg kg−1) or saline was injected 15 min before a subeffective dose of sildenafil (2.5 mg kg−1). Saline, L-NAME (5 mg kg−1) or MB (1 mg kg−1) was injected 15 min before an effective dose of sildenafil (10 mg kg−1). The threshold of bicuculine-induced clonic seizures was measured 30 min after sildenfil injection. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 compared with Saline/Saline group. ++P<0.01, +++P<0.001 compared with the group treated with Saline/Sildenafil (10 mg kg−1). Each group consisted of five to seven mice.

Effects of sildenafil citrate on generalized tonic seizure incidence and latency

Table 2 summarizes the effects of sildenafil (10 and 20 mg kg−1 or vehicle) on the incidence and latency of generalized tonic seizures induced by intraperitoneal PTZ (85 mg kg−1) administration. In vehicle-pretreated animals, tonic seizures followed by death occurred in 40% animals. There was no significant difference between the effects of sildenafil and vehicle on the incidence of tonic seizures and death or the latency of tonic seizures.

Table 2.

Effects of sildenafil on the latency and incidence of generalized tonic seizures

| Treatment | N | TSIa | TSLb | DIa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline | 15 | 6 (%40) | 428.0 (186.5, 669.4) | 6 (%40) |

| Sildenafil 10 mg kg−1 | 14 | 8 (%57) | 411.4 (170.2, 652.5) | 8 (%57) |

| Sildenafil 20 mg kg−1 | 15 | 8 (%53) | 379.4 (189.3, 569.4) | 8 (%53) |

The latency to the onset of tonic (TSL) generalized seizures as well as the incidence of tonic generalized seizures (TSI) and death (DI) was assessed following an intraperitoneal injection of 85 mg kg−1 PTZ. Saline or sildenafil (10 and 20 mg kg−1, subcutaneously) was administered 30 min before injection of PTZ. Seizure latencies (seconds after PTZ injection) are expressed as medians (with 95% confidence intervals) in each group. Tonic seizures in all mice led to death.

Pearson χ2, P>0.05.

Kruskal–Wallis H test, P>0.05.

Discussion

The present results indicate that sildenafil causes a dose-dependent decrease in the threshold of PTZ- and bicuculine-induced clonic seizures. This effect was specific to clonic type of seizures and did not generalize to tonic type of seizures induced by near maximal intraperitoneal PTZ administration. We also examined the possible role of NO–cGMP pathway in the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil and found evidence of interactions between NOS substrate L-Arginine, NO donor SNP and NOS inhibitor L-NAME and the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil. Together, this data suggest that the activation of NO–cGMP pathway plays a crucial role in the lowering of seizure threshold by sildenafil.

Sildenafil is known to selectively block PDE5 and enhance the NO-mediated effects by inhibiting cGMP degradation in target tissues, such as corpus cavernosum (Boolell et al., 1996; Jackson et al., 1999; Moreira et al., 2000). However, the extent and impact of central effects of sildenafil is largely unknown. Only recently, reports indicating some central effects of this drug have emerged from basic and clinical literature (Baratti & Boccia, 1999; Mixcoatl-Zecuatl et al., 2000; Moreira et al., 2000; Milman & Arnold, 2002; Gilad et al., 2002; Kurt et al., 2004). For example, several authors have described the modulation of antinociception by sildenafil in mechanistically distinct models of pain perception including tail-flick (spinal and supraspinal), hot plate (supraspinal) acetic acid writhing and formalin (peripheral) tests (Mixcoatl-Zecuatl et al., 2000; Asomoza-Espinosa et al., 2001; Jain et al., 2001; Ambriz-Tututi et al., 2005). In addition, Kurt et al. (2004) have reported that sildenafil causes an anxiogenic effect in the elevated plus maze in mice. Similarly, Volke et al. (2003) found a synergistic anxiogenic effect with the combination of sildenafil and NOS substrate L-arginine. The recent clinical evidence also suggest that sildenafil may have some central side effects (Gilad et al., 2002; Milman & Arnold, 2002). The mechanism of the reported central effects of sildenafil is not well understood but there are evidence that NO–cGMP pathway may play a role in the aforementioned central effects of sildenafil (Mixcoatl-Zecuatl et al., 2000; Asomoza-Espinosa et al., 2001; Jain et al., 2001; Volke et al., 2003; Kurt et al., 2004).

PTZ-induced chemical seizures provide a well-established paradigm for assessment of seizure susceptibility. PTZ binds to the picrotoxin site of the GABA receptor complex and blocks the GABA-mediated inhibition. This leads to a disinhibition of GABAergic transmission and a subsequent activation of excitatory transmission in major epileptogenic centers of forebrain like amygdale and piriform cortex (Gale, 1992; Kaputlu & Uzbay, 1997; Eells et al., 2004). In contrast to clonic seizures that are regulated by forebrain centers (Löscher & Schmidt, 1988; Eells et al., 2004), generalized tonic-clonic seizures are under brainstem regulation (Sarkisian, 2001; Eells et al., 2004). The clonic model is a more sensitive method for assessment of modulatory effects on convulsive tendency (Löscher et al., 1991; Löscher & Schmidt, 1988). Thus, the similar proconvulsant effects of sildenfil on PTZ- and bicuculine-induced clonic seizures suggest that this drug may influence the seizure-regulating centers of forebrain. Its lack of effect on measures of generalized tonic seizures would imply that these findings may have less relevance to grand mal type of seizures.

The present finding that the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil can be completely blocked by either NOS inhibitor L-NAME or guanylyl cyclase inhibitor MB, suggest direct evidence in favor of a NO-cGMP mediated modulation of seizure threshold by sildenafil. There is ample evidence that NO plays an important role in regulation of seizure threshold but the direction of its effects may depend on the type of seizure, source of NO and other neurotransmitter systems involved (De Sarro et al., 1991; Starr & Starr, 1993; Osonoe et al., 1994; Theard et al., 1995; Van Leeuwen et al., 1995; Tsuda et al., 1997; Nidhi et al., 1999). In chemical seizure paradigms induced by GABA antagonists, excessive release of NO, for example, after a large dose L-arginine administration, enhances the seizure susceptibility. This effect is likely a consequence of hyper-excitability caused by NO-induced cGMP synthesis (Garthwaite 1991). In addition, the endogenously released NO participates in the excitatory transmission through NMDA receptors (Manzoni et al., 1992) and strong blockade of NO synthesis, by high doses of NOS inhibitors, blocks the PTZ-induced seizures (present data, Homayoun et al., 2002b). Finally, NO may also reduce the activity of the inhibitory GABAergic receptors (Robello et al., 1996). In the present study, both NOS substrate and NO donor produced additive/synergistic interactions with the proconvulsant effect of sildenafil, further supporting the involvement of NO in this effect. The possibility that NO modulating drugs may alter the peak time of sildenafil effect should also be considered. However, this class of drugs shows similar interactions with sildenafil in other paradigms (Jain et al., 2001; Volke et al., 2003; Kurt et al., 2004). The present findings are also noteworthy in the context of possible proconvulsant interactions in patients taking both sildenafil and NO-releasing cardiovascular medications. Interestingly, a recent case report by Gilad et al. (2002) raised concerns about the proconvulsant side effects of sildenafil. While sildenafil is contraindicated in patients who are taking organic nitrates because of adverse cardiovascular consequences of its interaction with high nitrate levels (Leung & Yip, 1999), the present findings offer an additional reason for caution against simultaneous administration of sildenafil and NO-releasing drugs. It should be also noted that the effective dose range of sildenafil used in the present study in mice starts at doses of 5 and 10 mg kg−1 (for PTZ- and bicuculine-induced clonic seizures, respectively) that are higher than maximum clinical dose in man (approximately, 1.4 mg kg−1, Walker et al., 1999; Abbott et al., 2004). However, the elimination half live of sildenafil in mice is significantly less than man (<1 vs 2.4 h) and the mentioned doses are within the dose range that is considered devoid of any toxic effects in rodents (Abbott et al., 2004). Therefore, alteration of seizure threshold by sildenafil may have clinical relevance and warrants further investigation.

In conclusion, the present study is the first to report the proconvulsant effects of sildenafil in an experimental model of clonic seizure. Our findings suggest that NO–cGMP pathway may play a role in this increased susceptibility to seizures.

Abbreviations

- PTZ

pentylenetetrazole

References

- ABBOTT D., COMBY P., CHARUEL C., GRAEPEL P., HANTON G., LEBLANC B., LODOLA A., LONGEART L., PAULUS G., PETERS C., STADLER J. Preclinical safety profile of sildenafil. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2004;16:498–504. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AMBRIZ-TUTUTI M., VELAZQUEZ-ZAMORA D.A., URQUIZA-MARIN H., GRANADOS-SOTO V. Analysis of the mechanism underlying the peripheral antinociceptive action of sildenafil in the formalin test. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2005;512:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARAIZA-SALDANA C.I., REYES-GARCIA G., BERMUDEZ-OCANA D.Y., PEREZ-SEVERIANO F., GRANADOS-SOTO V. Effect of diabetes on the mechanisms of intrathecal antinociception of sildenafil in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2005;527:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASOMOZA-ESPINOSA R., ALONSO-LOPEZ R., MIXCOATL-ZECUATL T., AGUIRRE-BANUELOS P., TORRES-LOPEZ J.E., GRANADOS-SOTO V. Sildenafil increases diclofenac antinociception in the formalin test. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001;418:195–200. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00956-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARATTI C.M., BOCCIA M.M. Effects of sildenafil on long-term retention of an inhibitory avoidance response in mice. Behav. Pharmacol. 1999;10:731–737. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199912000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOOLELL M., ALLEN M.J., BALLARD S.A., GEPI-ATTEE S., MUIRHEAD G.J., NAYLOR A.M., OSTERLOH I.H., GINGELL C. Sildenafil: an orally active type 5 cyclic GMP-specific phosphodiesterase inhibitor for the treatment of penile erectile dysfunction. Int. J. Impot. Res. 1996;8:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOYCE E.G., UMLAND E.M. Sildenafil citrate: a therapeutic update. Clin. Ther. 2001;23:2–23. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUJAS-BOBANOVIC M., BIRD D.C., ROBERTSON H.A., DURSUN S.M. Blockade of phencyclidine-induced effects by a nitric oxide donor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:1005–1012. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CROSBY R., DICLEMENTE R.J. Use of recreational Viagra among men having sex with men. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2004;80:466–468. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.010496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE SARRO G.B., DONATO DI PAOLA E., DE SARRO A., VIDAL M.J. Role of nitric oxide in the genesis of excitatory amino acid-induced seizures from the deep prepiriform cortex. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 1991;5:503–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1991.tb00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EELLS J.B., CLOUGH R.W., BROWNING R.A., JOBE P.C. Comparative fos immunoreactivity in the brain after forebrain, brainstem, or combined seizures induced by electroshock, pentylenetetrazol, focally induced and audiogenic seizures in rats. Neuroscience. 2004;123:279–292. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALE K. Subcortical structures and pathways involved in convulsive seizure generation. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1992;9:264–277. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199204010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARTHWAITE J. Glutamate, nitric oxide and cell-cell signaling in the nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 1991;14:60–67. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90022-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILAD R., LAMPL Y., ESHEL Y., SADEH M. Tonic-clonic seizures in patients taking sildenafil. Brit. Med. J. 2002;325:869. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7369.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOMAYOUN H., KHAVANDGAR S., DEHPOUR A.R. Anticonvulsant effects of cyclosporin A on pentylenetetrazole-induced seizure and kindling: modulation by nitricoxidergic system. Brain Res. 2002a;939:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02533-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOMAYOUN H., KHAVANDGAR S., NAMIRANIAN K., GASKARI S.A., DEHPOUR A.R. The role of nitric oxide in anticonvulsant and proconvulsant effects of morphine in mice. Epilepsy Res. 2002b;48:33–41. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(01)00316-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HONAR H., RIAZI K., HOMAYOUN H., SADEGHIPOUR H., RASHIDI N., EBRAHIMKHANI M.R., MIRAZI N., DEHPOUR A.R. Ultra-low dose naltrexone potentiates the anticonvulsant effect of low dose morphine on clonic seizures. Neuroscience. 2004;129:733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JACKSON G., BENJAMIN N., JACKSON N., ALLEN M.J. Effects of sildenafil citrate on human hemodynamics. Am. J. Cardiol. 1999;83:13C–20C. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAIN N.K., PATIL C.S., SINGH A., KULKARNI S.K. Sildenafil-induced peripheral analgesia and activation of the nitric oxide-cyclic GMP pathway. Brain Res. 2001;909:170–178. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02673-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAPUTLU I., UZBAY T. L-NAME inhibits pentylenetetrazol and strychnine-induced seizures in mice. Brain Res. 1997;753:98–101. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01496-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUPFERBERG H. Animal models used in the screening of antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia. 2001;42 (Suppl 4):7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KURT M., BILGE S.S., AKSOZ E., KUKULA O., CELIK S., KESIM Y. Effect of sildenafil on anxiety in the plus-maze test in mice. Pol. J. Pharmacol. 2004;56:353–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEUNG L.S., YIP A.W.C. Sildenafil (Viagra®) and erectile dysfunction. Ann. Coll. Surg. 1999;4:99–102. [Google Scholar]

- LÖSCHER W., LEHMANN H. L-Deprenyl (selegiline) exerts anticonvulsant effects against different seizure types in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;277:1410–1417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LÖSCHER W., SCHMIDT D. Which animal models should be used in the search for new antiepileptic drugs? A proposal based on experimental and clinical considerations. Epilepsy Res. 1988;2:145–181. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(88)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LÖSCHER W., HONACK D., FASSBENDER C.P., NOLTING B. The role of technical, biological and pharmacological factors in the laboratory evaluation of anticonvulsant drugs: III. Pentylenetetrazole seizure models. Epilepsy Res. 1991;8:171–189. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(91)90062-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANZONI O., PREZEAU L., MARIN P., DESHAGER S., BOCKAERT J., FAGNI L. Nitric oxide-induced blockade of NMDA receptors. Neuron. 1992;8:653–662. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90087-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILMAN H.A., ARNOLD S.B. Neurologic, psychological, and aggressive disturbances with sildenafil. Ann. Pharmacother. 2002;36:1129–1134. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIXCOATL-ZECUATL T., AGUIRRE-BANUELOS P., GRANADOS-SOTO V. Sildenafil produces antinociception and increases morphine antinociception in the formalin test. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000;400:81–87. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00361-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONCADA S., PALMER R.M., HIGGS E.A. Nitric Oxide: Physiology, pathology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol. Rev. 1991;43:109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOREIRA S.G., JR, BRANNIGAN R.E., SPITZ A., OREJUELA F.J., LIPSHULTZ L.I., KIM E.D. Side-effect profile of sildenafil citrate (Viagra) in clinical practice. Urology. 2000;56:474–476. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00649-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIDHI G., BALAKRISHNAN S., PANDHI P. Role of nitric oxide in electroshock and pentylenetetrazole seizure threshold in rats. Meth. Find. Exp. Clin. Pharmacol. 1999;21:609–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OSONOE K., MORI N., SUZUKI K., OSONOE M. Antiepileptic effects of inhibitors of nitric oxide synthase examined in pentylenetetrazol-induced seizures in rats. Brain Res. 1994;663:338–340. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRICKAERTS J., VAN STAVEREN W.C., SIK A., MARKERINK-VAN ITTERSUM M., NIEWOHNER U., VAN DER STAAY F.J., BLOKLAND A., DE VENTE J. Effects of two selective phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, sildenafil and vardenafil, on object recognition memory and hippocampal cyclic GMP levels in the rat. Neuroscience. 2002;113:351–361. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00199-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBELLO M., AMICO C., BUCOSSI G., CUPELLO A., RAPALLINO M.V., THELLUNG S. Nitric oxide and GABAA receptor function in the rat cerebral cortex and cerebellar granule cells. Neuroscience. 1996;74:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARKISIAN M.R. Overview of the current animal models for human seizure and epileptic disorders. Epilepsy Behav. 2001;2:201–216. doi: 10.1006/ebeh.2001.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHAFAROODI H., SAMINI M., MOEZI L., HOMAYOUN H., SADEGHIPOUR H., TAVAKOLI S., HAJRASOULIHA A.R., DEHPOUR A.R. The interaction of cannabinoids and opioids on pentylenetetrazole-induced seizure threshold in mice. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:390–400. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH J.B., OGONOWSKI A.A. Behavioral effects of NMDA receptor agonists and antagonists in combination with nitric oxide-related compounds. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003;471:121–128. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01820-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SNYDER S.H., BREDT D.S. Nitric oxide as a neural messenger. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1991;12:125–128. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90526-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STARR M.S., STARR B.S. Paradoxical facilitation of pilocarpine-induced seizures in the mouse by MK-801 and the nitric oxide synthesis inhibitor L-NAME. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1993;45:321–325. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90246-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SWINYARD E.A., KUPFERBERG H.J. Antiepileptic drugs: detection, quantification, and evaluation. Fed. Proc. 1985;44:2629–2633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THEARD M.A., BAUGHMAN V.L., WANG Q., PELLIGRINO D.A., ALBRECHT R.F. The role of nitric oxide in modulating brain activity and blood flow during seizure. Neuroreport. 1995;6:921–924. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199504190-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSUDA M., SUZUKI T., MISAWA M. Aggravation of DMCM-induced seizure by nitric oxide synthase inhibitors in mice. Life Sci. 1997;60:PL339–PL343. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN LEEUWEN R., DE VRIES R., DZOLJIC M.R. 7-Nitroindazole, an inhibitor of neuronal nitric oxide synthase, attenuates pilocarpine-induced seizures. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;287:211–233. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00678-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VOLKE V., WEGENER G., VASAR E. Augmentation of the NO-cGMP cascade induces anxiogenic-like effect in mice. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2003;54:653–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALKER D.K., ACKLAND M.J., JAMES G.C., MUIRHEAD G.J., RANCE D.J., WASTALL P., WRIGHT P.A. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of sildenafil in mouse, rat, rabbit, dog and man. Xenobiotica. 1999;29:297–310. doi: 10.1080/004982599238687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]