Abstract

Condensed Abstract

Preclinical studies suggest that retinoids have the potential to inhibit the development of lung cancer while they have disappointed in clinical trials. The current study shows that the retinoids 9-Cis-retinoic acid and 13-Cis-retinoic acid stimulate via cAMP/PKA-dependent signaling the proliferation of human lung adenocarcinoma cells and small airway epithelial cells while inhibiting the proliferation of small cell lung carcinoma cells and large airway epithelial cells.

Background

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide. A diet rich in fruit and vegetables has been shown to reduce the lung cancer risk. However, clinical trials with beta-carotene and retinoids have disappointed, resulted in increased mortality from lung cancer and cardiovascular disease.

Methods

We have investigated the effects of the two major retinol metabolites, 9-cis-retinoic acid (9-Cis-RA), and 13-cis-retinoic acid (13-Cis-RA), on cell proliferation (MTT assays), intracellular cAMP (cAMP immunoassays), PKA activation (non-radioactive PKA activation assays), and ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Western blots) in immortalized human small airway epithelial cells, HPL1D, a human lung adenocarcinoma cell line, NCI-H322, immortalized human bronchial epithelial cells, BEAS-2B, and in the human small cell lung carcinoma cell line, NCI-H69.

Results

Both retinoids increased intracellular cAMP and PKA activation in all cell lines. In BEAS-2B and NCI-H69 cells, the stimulation of cAMP/PKA reduced the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and inhibited cell proliferation whereas phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and cell proliferation were increased in HPL1D and NCI-H322 cells.

Conclusions

Our data have identified a novel mechanism of action of 9-Cis-RA and 13-Cis-RA: activation of PKA in response to increased cAMP. The observed stimulation of cAMP/PKA may inhibit the development of small cell lung carcinoma and other tumors derived from large airway epithelia whereas it may selectively promote the development of lung tumors derived from small airway epithelial cells, such as adenocarcinoma.

Keywords: retinoid signaling, PKA, ERK1/2, lung adenocarcinoma, small cell lung carcinoma , small airway epithelial cell, large airway epithelial cell

List of Abbreviations: RA: Retinoic acid; cAMP: Cyclic Adenosine monophosphate; PKA: Protein Kinase-A; MTT: 3-(4,5-dimethyle thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide; ERK1/2: Extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2; ATBC: Alpha-tocopherol, beta-carotene trial; CARET: Beta-carotene and Retinoid e=Efficacy trial; NNK: 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone; CREB: cAMP response element binding protein; EGFR: Epidermal growth factor receptor; PKC: Protein kinase-C; DMSO: Dimethyl sulfoxide; ANOVA: Analysis of variance; IBMX: Isobutyl-1- methylxanthine; PBS: Phosphate buffered saline; EDTA: Ethylene-diamine tetraacetic acid

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide (1, 2). Adenocarcinoma and small cell carcinoma are among the most common histological types of lung cancer. Adenocarcinoma is thought to be derived from epithelial cells that line the peripheral small airways, whereas small cell carcinoma is thought to be mainly derived from epithelial cells that line centrally located large airways (3). The high mortality rate of this family of malignancies is caused by a frequent lack of responsiveness to existing therapeutic strategies and the absence of effective diagnostic tools for the early detection of premalignant lesions. Efforts to prevent the development of overt lung cancer in individuals at risk due to exposure to cigarette smoke and occupational risk factors have therefore been a major focus of lung cancer research during the past two decades. Epidemiological studies have shown that a diet rich in fruit and vegetables reduces the lung cancer risk (4, 5). Vitamin A (retinol), its natural precursor, beta-carotene, the metabolites 9-cis retinoic acid (9-Cis-RA) and 13-cis retinoic acid (13-Cis-RA) formed from retinol and commonly referred to as retinoids, as well as synthetic retinoids have thus been extensively tested in preclinical and clinical studies. Preclinical studies have shown in vivo and in vitro inhibition of chemically induced carcinogenesis by retinoids or the pro-vitamin β-carotene (6–9). In addition, vitamin A-deficiency was reported to cause squamous cell metaplasia in cultured respiratory epithelium of hamsters and this change was reversed by in vitro treatment with retinoids (10, 11). However, this family of chemopreventive agents has failed in clinical trials (12–14). An α-tocopherol, β-carotene supplementation trial (ATBC) and a chemoprevention trial with β-carotene and retinoids (β-carotene and retinoid efficacy “CARET” trial) were conducted in the 1990s in populations at risk for the development of lung cancer because of previous or current exposure to smoking or asbestos (12–14). Both trials had to be discontinued due to an increase in lung cancer incidence (28%) and mortality (46%) and a 26% increase in cardiovascular mortality in the CARET trial and an 18% increase in lung cancer incidence and 8% increase in cardiovascular mortality in the β-carotene group of the ATBC trial. Conclusive explanations for these unfortunate outcomes have not been provided to date.

Lung adenocarcinomas induced in hamsters by the tobacco-specific nitrosamine, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK), derive from the epithelial lining cells of small peripheral airways and express the CC10 protein characteristic for bronchiolar Clara cells(15, 16). It has recently been shown that these tumors over-expressed β-adrenergic receptors (β-ARs) and their downstream effectors, protein kinase A (PKA) and the phosphorylated transcription factor CREB, while simultaneously over-expressing phosphorylated epidermal grow factor receptor (EGFR)-specific tyrosine kinases and their downstream effectors (16), phosphorylated extracellular signal regulated kinases (ERK1/2) (16). These findings suggested a potential cross talk between signaling involving cAMP/PKA/CREB and the EGFR signaling cascade in human lung adenocarcinomas of small airway epithelial cell origin (17). In vitro studies with the human lung adenocarcinoma cell line, NCI-H322, which expresses the Clara cell-specific CC10 protein, and with the immortalized cell line, HPL1D, established from human peripheral small airway epithelial cells and also expressing the CC10 protein, showed that β 1 -adrenergic signaling induced by NNK or a classic β 1 -adrenergic receptor agonist caused a significant stimulation of DNA synthesis in both cell lines. This effect was further increased by transient overexpression of the β 1 -adrenergic receptor and inhibited by pretreatment of the cells with a β 1 -adrenergic receptor antagonist, an inhibitor of PKA, or an inhibitor of EGFR specific tyrosine kinases (17). Transactivation of the EGFR was suggested by NNK-induced phosphorylation of the EGFR at four specific tyrosine kinase sites that was blocked by a β 1 -adrenergic receptor antagonist or an inhibitor of PKA (17). In addition, it has been shown that the pro-vitamin, beta-carotene, as well as vitamin A itself (retinol) increased the intracellular concentration of cAMP in NCI-H322 and HPL1D cells and that this response triggered the activation of ERK1/2 and cell proliferation in a PKA-dependent manner (18). By contrast, the proliferation of the immortalized cell line, BEAS-2B, established from human epithelial lining cells of large centrally located airways, was inhibited by β-carotene and retinol (19). Furthermore, it has been shown that cell lines derived from human small cell lung carcinoma are stimulated by autocrine loops initiated by serotonergic and neuropeptide signaling and involving the activation of protein kinase C (PKC), Raf and ERK1/2 downstream (20–23). The phosphodiesterase inhibitor, theophylline, inhibited these mitogenic loops via increase of intracellular cAMP in vitro and has therefore been proposed as a potential therapeutic agent for small cell lung carcinoma (24).

In the current study, we have investigated the effects of the two major retinol metabolites, 9-cis-retinoic acid (9-Cis-RA), and 13-cis-retinoic acid (13-Cis-RA), on cell number, intracellular cAMP, PKA activation, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in NCI-H322, HPL1D, BEAS-2B cells, and in the human small cell lung carcinoma cell line, NCI-H69. Our data provide evidence, for the first time, that both retinoids inhibit the growth of small cell lung carcinoma and large airway epithelial cells by stimulation of cAMP/PKA signaling while increasing the proliferation of lung adenocarcinoma and small airway epithelial cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and tissue culture

The human lung adenocarcinoma cell line with characteristics of Clara cells, NCI-H322 (Center for Applied Microbiology and Research (ECACC, Salisbury, Wiltshire, UK), and the human cell line, NCI-H69 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA), established from a centrally located small cell lung carcinoma, were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (American Type Culture Collection) supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 mM Hepes, 1mM sodium pyruvate, 2mM L-glutamine, 4500 mg/l glucose, and 1500mg/l sodium bicarbonate. The Simian virus 40 (SV40)-immortalized human cell line HPL1D, established from the epithelial lining cells of peripheral small airways, was a kind gift from Dr. Takahashi (25). These cells were maintained in F-12 (HAM; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) medium supplemented with 1% fetal calf serum, 15mM HEPES pH 7.3, 5 μg/ml insulin, 5 μg/ml transferrin, 10−7 M hydrocortisone, and 2x10−10 M triiodothyronine (Cambrex, Walkersville, MD). The SV40/adenovirus/12 hybrid virus immortalized cell line, BEAS-2B (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD), established from epithelial lining cells of human large centrally located airways, was maintained in bronchial epithelial cell basal medium (BEBM) supplemented with 2 ml bovine pituitary extract, 0,5 ml insulin, 0.5 ml hydrocortisone, 0.5 ml retinoic acid, 0.5 ml transferrin, 0.5 ml triiodothyronine, 0.5 ml epinephrine, and 0.5 ml human epidermal growth factor. All tested cell lines were maintained in antibiotic-free medium in an environment of 5% CO2. Assays with NCI-H322 cells were conducted in low-serum (0.1% fetal bovine serum) RPMI medium while assays with HPLD1 or BEAS-2B cells were conducted in their basal media without supplements.

Assessment of cell proliferation by MTT assay

We have previously established that activation of ERK1/2 in a β 1 -adrenergic receptor and PKA-dependent manner stimulates DNA synthesis in NCI-H322 and HPL1D cells (17) while DNA synthesis in small cell lung carcinoma cells was stimulated by nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-mediated and Raf-1-dependent activation of ERK1/2 (20, 21). In the current study, we used the colorimetric 3-(4, 5-dimethyle thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (Sigma) as previously described (2) to assess the effects of 9-Cis-RA and 13-Cis-RA (Sigma, St Louis) on these mitogenic signaling cascades. The MTT test is based on the NADH-dependent enzymatic reduction of the tetrazolium salt MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazoliumbromide] in metabolically active cells but not in dead cells, thus measuring the number of viable cells. While both cell proliferation and apoptosis regulate viable cell numbers, the investigated signaling pathways have been clearly linked with DNA synthesis indicative of cell proliferation in previous experiments with the cell lines under study (17, 20, 21). Cells that grow as monolayers (NCI-H322, HPL1D, BEAS-2B) were seeded into 6-well tissue culture plates (Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) at a density of 50,000 cells per well in their respective complete media and left to grow at 37°C for 5 hours. NCI-H322 cells were then switched to fresh phenol red-free low serum (0.1% FBS) RPMI medium while HPL1D or BEAS-2B cells were switched to their respective basal media without additives. NCI-H69 cells, which grow as floating cell aggregates, were seeded in phenol red-free, low serum RPMI medium. The retinoids, 9-Cis-RA or 13-Cis-RA, dissolved in DMSO, were added to the wells to yield the final concentrations specified in the figure legends and incubated for 48 or72 hours as specified in the figure legends. Preliminary tests with DMSO treated versus untreated cells indicated that DMSO had no effect in the MTT assay (data not shown). Cells treated with DMSO alone therefore served as controls. Pre-incubation of cells with an inhibitor of adenylate cyclase (SQ22536) or of PKA (H89) at the concentrations specified in the figure legends was for 10 minutes. Three hours before the end of the incubation time, 100 μl of 3-(4, 5-dimethyl thiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (0.5 mg/ml) dissolved in phenol red-free medium was added to allow for the metabolic conversion of the MTT substrate to blue formazan. The media were replaced with isopropanol, and optical density at 570 nm was determined using an ELISA reader.

Data are expressed as mean values and standard errors of four samples per treatment group. Each experiment was repeated twice and yielded similar data. The viability of cells under the exposure conditions used was monitored by trypan blue dye exclusion.

CAMP Immunoassay

Cells from adherent monolayers (NCI-H322, HPL1D, BEAS-2B) were plated at 4X105 cells per well in their respective complete media in 6-well plates and grown until 65-70 % confluence. The medium was changed to low serum (0.1% FBS), phenol red-free RPMI (NCI-H322), basal F-12 (HPL1D), or BEBM (BEAS-2B) medium for 24 hours, washed with 1X PBS. NCI-H69 cells were plated at 4X105 cells/well in low serum (0.1% FBS) phenol red-free RPMI medium in 6-well plates. The retinoids, 9-Cis-RA (20nM) or 13-Cis-RA (20nM), dissolved in DMSO and IBM (1mM) were added to each well for 10 or 30 min. After 3 washes with 1X PBS, cells were treated with 0.1 M HCL for 20 min, then, lysed by sonication. After centrifugation, samples were analyzed for cAMP levels using a direct cyclic AMP enzyme immunoassay kit according to the manufacturer instructions (Assay Designs Inc, Ann Arbor, Mi). Briefly, the assay utilizes p-nitrophenyl phosphate as a substrate and a polyclonal antibody to cAMP that binds to the cAMP in sample. Reactions were stopped with trisodium phosphate and color intensity was measured at 405 nm. Data are expressed as mean values and standard errors of triplicate samples per treatment group. The experiments were repeated twice with each repetition yielding similar data.

PKA Activation Assay

Following incubation of cells with 9-Cis-RA or 13-Cis-RA in DMSO for 5 minutes to 2 hours as at the concentrations specified in the figure legends, PKA activity was assayed in cell lysates using a Pep Tag assay for non-radioactive detection of activated PKA (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA), following the instruction of the manufacturer. This assay utilizes fluorescent substrate for PKA that changes the peptide’s net charge upon phosphorylation of PKA, thus allowing the phosphorylated peptide to migrate to the positive electrode, while the non-phosphorylated peptide migrates to the negative electrode. Briefly, reaction mixtures containing a brightly colored fluorescent peptag A1 peptide (0.4 μg/ml), peptide protection, peptag PKA reaction, and PKA activator solutions were incubated on ice for five minutes followed by one minute at 30°C. Samples were then added, and the mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 30° minutes, heated to 95° C for 10 minutes, and loaded onto 0.8% agarose gel in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). The protein kinase A activity in the samples was determined by examining the gel under UV light. Following inversion of the images to yield the bands black and the background grey, the density of each band was quantitatively assessed by image analysis using NIH Scion image analysis software. Five densitometric readings per band were taken and mean values and standard errors were calculated. Each experiment was repeated once with similar results.

Assessment of total proteins and phosphorylated proteins by Western blotting

To assess the effects of 9-Cis-RA or 13-Cis-RA on the expression and phosphorylation of the mitogen activated protein kinases ERK1/2, 500,000 cells were seeded into culture vessels (100 cm2) containing their respective growth media. When the adherent cells had reached 60–65% confluence, they were rinsed one time with 1X PBS and serum-starved (0.1%FBS) for 24 hours. NCI-H69 cells were directly seeded into low serum (0.1% FBS) medium. Following removal of the media and replacement with fresh low-serum media, 9-Cis-RA or 13-Cis-RA (dissolved in DMSO) was added to the culture vessels and cells were incubated from five minutes to one hour at the concentrations detailed in the figure legends. Cells exposed to the retinoid vehicle (DMSO) served as controls. The cultured cells then were washed once with cold PBS, lysed in 20 mM Tris-base, 200 mM NaCl, 1 M sodium fluoride. 0.5 M EDTA, 100 mM Na3VO4, 100 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1μl pepstatin, 1 μl leupeptin, 1 μl aprotinin, and 0.25 % NP-40. Protein samples were denatured by heating to 95°C for five minutes, separated on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel, and transferred to nitrocellulose. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in 1X tris-buffered saline tween-20, and then incubated over night at 4°C with primary antibodies at a 1:1000 dilution (rabbit polyclonal for total ERK1/2, rabbit polyclonal for Thr202/Tyr204 phosphorylated Erk1/2 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA). Five densitometric readings per band (NIH Scion image analysis software) were taken and mean values and standard errors were calculated. Each experiment was repeated twice and yielded similar data.

Statistical Evaluation of Data

Statistical analysis of all data was by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test, and two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Results

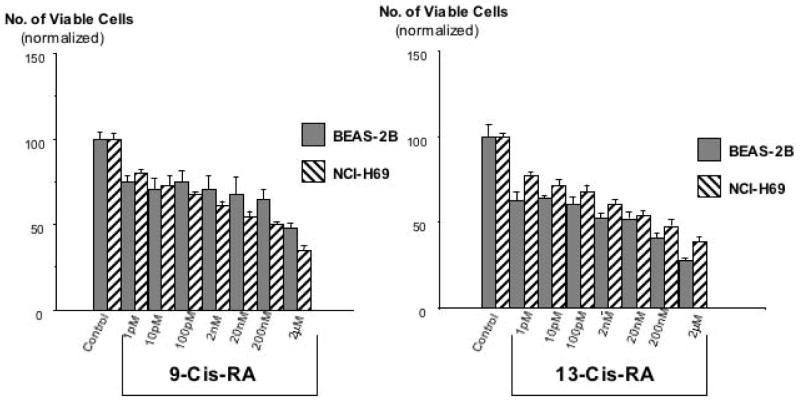

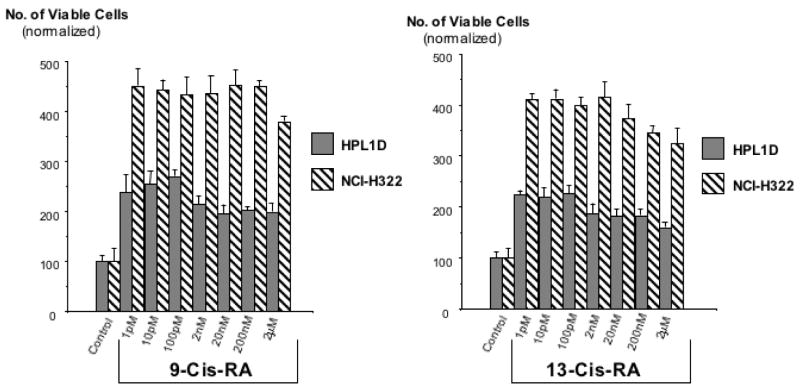

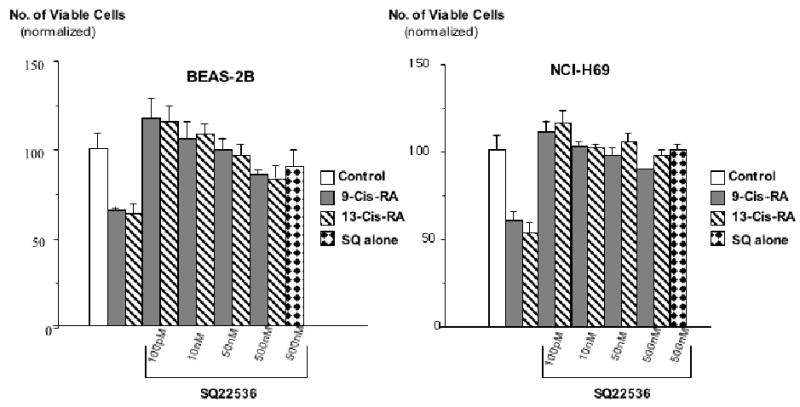

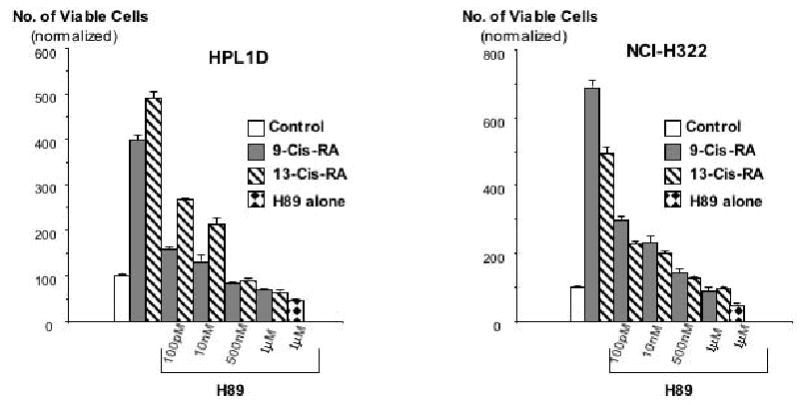

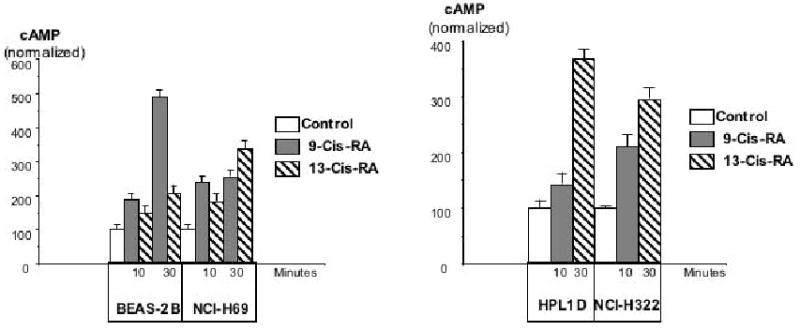

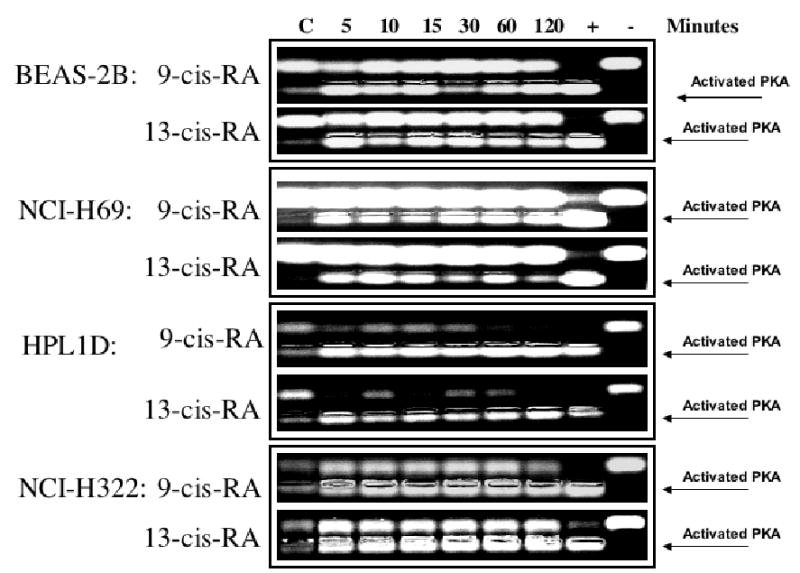

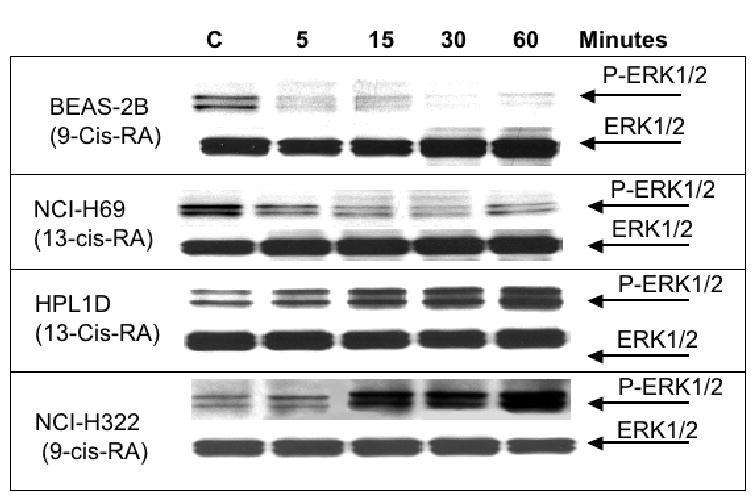

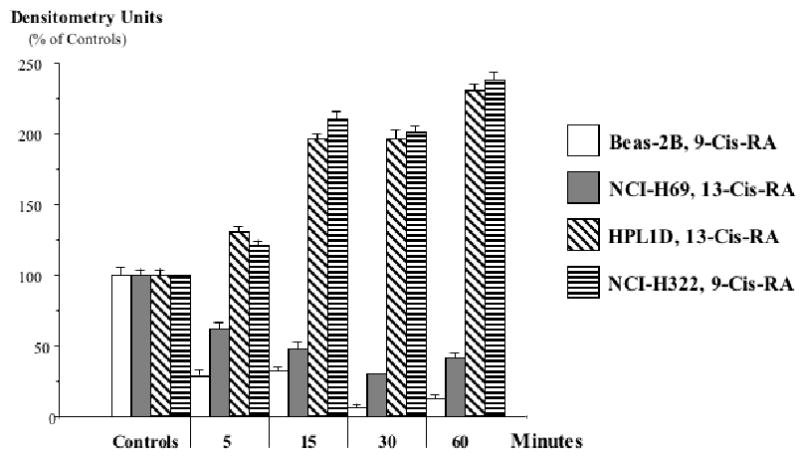

Analysis of cell proliferation by MTT assays revealed significant (p<0.001) and concentration-dependent growth inhibiting effects of 9-Cis-RA and 13-Cis-RA after 72 hours of incubation at concentrations from 1 pM to 2 μM in the large airway epithelial cells, BEAS-2B, and in the small cell lung carcinoma cells, NCI-H69 (Figure 1). Maximum inhibition of proliferation (35% of controls with 9-Cis-RA; 38.5% of controls with 13-Cis-RA) was observed with the highest concentration (2 μM) of each retinoid in NCI-H69 cells. BEAS-2B cells were similarly responsive, with 9-Cis-RA reducing cell proliferation to 48% of the controls and 13-Cis-RA to 27.5% of controls at the2 μM concentration (Figure 1). The MTT assays with the small airway epithelial cells, HPL1D, and the adenocarcinoma cells, NCI-H322, used incubation periods with the retinoids of 48 hours to accommodate for the faster basal growth rate of these cells. Contrary to BEAS-2B and NCI-H69 cells, each of these cell lines responded with a significant (p<0.001) increase in cell proliferation to both retinoids at all concentrations (1 pM to 2 μM) tested (Figure 2). This effect was particularly prominent in the adenocarcinoma cells, which showed up to 4.5-fold increased numbers of viable cells when exposed to 9-Cis-RA and up to 4.3-fold increase when exposed to 13-Cis-RA (Figure 2). Interestingly, stimulation of cell proliferation was highest in response to the lower concentrations of the retinoids in both cell lines. The inhibitor of adenylase cyclase, SQ22536, or the inhibitor of PKA, H89, each significantly reduced the observed responses to both retinoids in all four-cell lines. As exemplified in Figure 3, the reduction in cell proliferation observed in BEAS-2B and NCI-H69 cells in response to either of the two retinoids (20 nM) was thus completely blocked (p < 0.001) by SQ22536 at all concentrations tested (100pM-500nM). On the other hand, the inhibition of cell proliferation by either retinoid (20nM) in HPL1D and NCI-H322 cells was significantly (p<0.001) reduced in a concentration-dependent manner (exemplified with H89 in Figure 4), with complete abrogation of the effect observed at the highest inhibitor concentration (1μM). Collectively, these findings suggest that cAMP/PKA signaling mediated both, the growth inhibiting and the growth stimulating responses to 9-Cis and 13-Cis-RA in our four cell lines. This interpretation was supported by the results of the cAMP immunoassays (Figure 5) and the PKA activation assays (Figure 6). Each of the four cell lines demonstrated significant (p<0.001) increases in intracellular cAMP after 10 and 30 minutes of exposure to 9-Cis-RA (20nM) or 13-Cis-RA (20nM), with peak values in all cell lines at the 30-minute time interval (Figure 5). In accord with these findings, PKA was activated by 9-Cis-RA and 13-Cis-RA in all four-cell lines after 5–120 minutes of exposure as evidenced by migration of the phosphorylated peptide to the positive electrode (Figure 6). Western blots which monitored the expression of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated ERK1/2 proteins over time in response to 9-Cis-RA (20nM) or 13-Cis-RA (20nM) revealed a pronounced reduction in the intensity of P-ERK1/2 bands in BEAS-2B and NCI-H69 cells exposed to either retinoid at all time intervals (5–60 minutes; exemplified in Figure 7). By contrast, the bands for P-ERK1/2 increased in size and density in HPL1D and NCI-H322 cells when exposed to 9-or-13-Cis-RA (shown in Figure 7). Densitometric analysis of the bands followed by statistical evaluation of these data confirmed a highly significant (p<0.001) reduction in densitometry readings of BEAS-2B and NCI-H69 cells at all time intervals tested (Figure 8). By contrast, densitometry readings for HPL1D and NCI-H322 cells increased significantly (p<0.001) at all time intervals (Figure 8). The observed decrease in p-ERK1/2 in BEAS-2B and NCI-H69 cells is in accord with the inhibition of cell proliferation observed in the MTT assays in response to both retinoids (Figure 1). Conversely, the observed increase in p-ERK1/2 in HPL1D and NCI-H322 cells correlates with the stimulation of cell proliferation by both retinoids observed in these cells (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Results of MTT assays for the assessment of cell proliferation in the human large airway epithelial cells, BEAS-2B, and the human small cell lung carcinoma cells, NCI-H69, after exposure for 72 hours to 9-Cis-RA or 13-Cis-RA. Both cell lines responded with a concentration-dependent reduction in cell numbers. The observed responses were highly significant (P<0.001) at all retinoid concentrations tested. Data are mean values and standard errors of four samples per treatment group. Each assay was repeated twice and yielded similar data.

Figure 2.

Results of MTT assay for the assessment of cell proliferation in the human small airway epithelial cells, HPL1D, and the human lung adenocarcinoma cells, NCI-H322 after exposure for 48 hours to 9-Cis-RA or 13-Cis-RA. Both cell lines responded with an increase in cell numbers. The observed responses were highly significant (P<0.001) at all retinoid concentrations tested. Data are mean values and standard errors of four samples per treatment group. Each assay was repeated twice with similar results.

Figure 3.

Results of MTT assays, illustrating the effects of pre-incubation (10 minutes) with the adenylate cyclase inhibitor, SQ22536, on the response of large airway epithelial cells BEAS-2B and small cell lung carcinoma cells NCI-H69 cells to 9-Cis-RA or 13-Cis-RA. The retinoid-induced reduction of cell proliferation was completely abrogated by all concentrations of SQ22536 in both cell lines. These effects of SQ22536 were highly significant (P<0.001). Data are mean values and standard errors of four samples per treatment group. Each assay was repeated twice and yielded similar results.

Figure 4.

Results of MTT assays, illustrating the effects of pre-incubation (20 minutes) with the PKA inhibitor, H89, on the responses of small airway epithelial cells HPL1D and lung adenocarcinoma cells NCI-H322 to 9-Cis-RA or 13-Cis-RA. The retinoid-induced stimulation of cell proliferation was inhibited by H89 in a concentration-dependent manner. These effects of H89 were highly significant (P<0.001). Data are mean values and standard errors of four samples per treatment group. Each assay was repeated twice and yielded similar results.

Figure 5.

Effects of 9-Cis-RA or 13-Cis-RA on intracellular cAMP as assessed by a cAMP immunoassay in large airway epithelial cells BEAS-2B, small cell lung carcinoma cells NCI-H69, small airway epithelial cells HPL1D, or lung adenocarcinoma cells NCI-H322 after 10 and 30 minutes of incubation. Each retinoid significantly (P<0.001) increased the concentration of cAMP in each cell line. Data are mean values and standard errors of triplicate samples per treatment group. Each assay was repeated twice and yielded similar results.

Figure 6.

PKA activation over time in response to 9-Cis-RA or 13-Cis-RA in large airway epithelial cells BEAS-2B, small cell lung carcinoma cells NCI-H69, small airway epithelial cells HPL1D, and lung adenocarcinoma cells NCI-H322 as assessed by a non-radioactive PKA activation assay. Each retinoid activated PKA in each cell line at all time intervals tested.

Figure 7.

Western blot, indicating the effects of 9-Cis-RA or 13-Cis-RA on the expression of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated ERK1/2 proteins. Each retinoid decreased the expression of P-ERKL1/2 in large airway epithelial cells BEAS-2B and small cell lung carcinoma cells NCI-H69. By contrast, small airway epithelial cells HPL1D and lung adenocarcinoma cells NCI-H322 responded with an increase in P-ERK1/2 expression.

Figure 8.

Quantitative assessment by densitometry of P-ERK1/2 expression in the Western blots of Figure 7. The observed decrease in P-ERK1/2 caused by 9-Cis-RA or 13-Cis-RA in large airway epithelial cells BEAS-2B and small cell lung carcinoma cells NCI-H69 was highly significant (p<0.001) at all time intervals tested, as was the increase in P-ERK1/2 expression observed in small airway epithelial cells HPL1D and lung adenocarcinoma cells NCI-H322. Data are mean values and standard errors of five densitometric readings per band.

Discussion

Our data show, for the first time, that the retinoids, 9-Cis-RA and 13-Cis-RA, increase intracellular cAMP, resulting in the activation of PKA. Our data further document that this novel mechanism of action results in the inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation and cell proliferation in some cell types (in our study BEAS-2B and NCI-H69) while yielding the opposite effects (increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation and cell proliferation) in other cells including HPL1D and NCI-H322 cells in our experiments. ERK1/2-mediated cell proliferation is stimulated in numerous cell types by a variety of growth factors. It has thus been shown that serotonergic and neuropeptide autocrine growth factors activate protein kinase C, Raf-1, ERK1/2 and c-myc in human small cell lung carcinoma cell lines, including NCI-H69 (20–23). It has also been shown that the cell cycle in BEAS-2B cells is regulated by the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway (26), which includes the activation of ERK1/2 downstream of tyrosine kinases and ras. In addition, the EGFR pathway is frequently over-expressed in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung (27, 28), a cancer type thought to arise from large airway epithelial cells. Theophylline, which increases intracellular cAMP by inhibiting the enzyme phosphodiesterase, was reported to inhibit the in vitro growth of human small cell lung carcinoma cell lines (24). In fact, phosphodiesterase inhibitors have been proposed as anti-cancer drugs (29). On the other hand, recent studies have shown that DNA synthesis in HPL1D and NCI-H322 cells is stimulated by cAMP/PKA signaling following binding of NNK to β-adrenergic receptors (17). This response involved the transactivation of EGFR-specific tyrosine kinase sites, resulting in the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (17). In addition, it has been shown that beta-carotene and retinol increased intracellular cAMP by an as yet undetermined mechanism, resulting in an inhibition of proliferation in BEAS-2B cells while stimulating the growth of HPL1D and NCI-H322 cells (18). In accord with these in vitro findings, studies in hamsters have shown that theophylline inhibited the development of neuroendocrine lung tumors with features of small cell lung carcinoma induced by NNK in animals with hyperoxic lung injury whereas it promoted the development of adenocarcinomas derived from bronchiolar Clara cells induced by NNK in healthy animals (30). In addition, the NNK-induced adenocarcinomas over-expressed β-adrenergic receptors and their effectors, PKA, phosphorylated CREB, while at the same time over-expressing the EGFR and its effectors, phosphorylated EGFR tyrosine kinases, Raf-1, and phosphorylated ERK1/2 (16).

While the mechanism(s) of how the retinoids increase intracellular cAMP remain to be determined, our data suggest that the observed stimulation of cAMP/PKA signaling may inhibit the development of small cell lung carcinoma and other malignancies derived from large airway epithelial cells whereas they may selectively promote the development of lung tumors derived from small airway epithelial cells, such as adenocarcinoma. The unfortunate outcomes of the ATBC and CARET trials support this hypothesis in that both trials not only caused increased lung cancer mortality, but additionally increased mortality from cardiovascular disease (12, 14). It is well established that increased β-adrenergic signaling via cAMP/PKA is an important factor in the etiology of cardiovascular disease. In fact, β-AR antagonists (beta-blockers) are at the forefront of cardiovascular therapeutics (31). Hence, it appears that the retinoid-induced stimulation of cAMP/PKA signaling reported by us not only contributed to the increased lung cancer burden but also to the increased cardiovascular mortality in the ATBC and CARET trials.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants RO1 CA088809 and RO1-CA096128 with the National Cancer Institute.

References

- 1.Weir HK, Thun MJ, Hankey BF, Ries LA, Howe HL, Wingo PA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2000, featuring the uses of surveillance data for cancer prevention and control. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1276–1299. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ezzati M, Henley SJ, Lopez AD, Thun MJ. Role of smoking in global and regional cancer epidemiology: current patterns and data needs. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:963–971. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garber ME, Troyanskaya OG, Schluens K, Petersen S, Thaesler Z, Pacyna-Gengelbach M, et al. Diversity of gene expression in adenocarcinoma of the lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13784–13789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241500798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith-Warner SA, Spiegelman D, Yaun SS, Albanes D, Beeson WL, van den Brandt PA, et al. Fruits, vegetables and lung cancer: a pooled analysis of cohort studies. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:1001–1011. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller AB, Altenburg HP, Bueno-de-Mesquita B, Boshuizen HC, Agudo A, Berrino F, et al. Fruits and vegetables and lung cancer: findings from the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:269–276. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langenfeld J, Lonardo F, Kiyokawa H, Passalaris T, Ahn MJ, Rusch V, et al. Inhibited transformation of immortalized human bronchial epithelial cells by retinoic acid is linked to cyclin E down-regulation. Oncogene. 1996;13:1983–1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moon RC, Rao KV, Detrisac CJ, Kelloff GJ. Hamster lung cancer model of carcinogenesis and chemoprevention. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1992;320:55–61. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-3468-6_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sporn MB, Dunlop NM, Newton DL, Smith JM. Prevention of chemical carcinogenesis by vitamin A and its synthetic analogs (retinoids) Fed Proc. 1976;35:1332–1338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sporn MB, Newton DL. Chemoprevention of cancer with retinoids. Fed Proc. 1979;38:2528–2534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris CC, Sporn MB, Kaufman DG, Smith JM, Jackson FE, Saffiotti U. Histogenesis of squamous metaplasia in the hamster tracheal epithelium caused by vitamin A deficiency or benzo[a]pyrene-Ferric oxide. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1972;48:743–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clamon GH, Sporn MB, Smith JM, Saffiotti U. Alpha- and beta-retinyl acetate reverse metaplasias of vitamin A deficiency in hamster trachea in organ culture. Nature. 1974;250:64–66. doi: 10.1038/250064a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The effect of vitamin E beta carotene on the incidence of lung cancer and other cancers in male smokers. The Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta Carotene Cancer Prevention Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1029–1035. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404143301501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen V, Khuri FR. Chemoprevention of lung cancer. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2004;10:279–283. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000129754.97392.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omenn GS, Goodman GE, Thornquist MD, Balmes J, Cullen MR, Glass A, et al. Effects of a combination of beta carotene and vitamin A on lung cancer and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1150–1155. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605023341802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuller HM, Witschi HP, Nylen E, Joshi PA, Correa E, Becker KL. Pathobiology of lung tumors induced in hamsters by 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone and the modulating effect of hyperoxia. Cancer Res. 1990;50:1960–1965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuller HM, Cekanova M. NNK-induced hamster lung adenocarcinomas over-express beta2-adrenergic and EGFR signaling pathways. Lung Cancer. 2005;49:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laag EM, Majidi M, Cekanova M, Masi T, Takahashi T, Schuller HM. NNK activates ERK1/2 and CREB/ATF-1 via beta-AR and EGFR signaling in human lung adenocarcinoma and small airway epithelial cells. Int J Cancer. 2006 doi: 10.1002/ijc.21987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Wadei HA, Takahashi T, Schuller HM. Growth stimulation of human pulmonary adenocarcinoma cells and small airway epithelial cells by beta-carotene via activation of cAMP, PKA, CREB and ERK1/2. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1370–1380. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Wadei HAN, Takahashi T, Schuller HM. Growth stimulation of human pulmonary adenocarcinoma cells and small airway epitheial cells by beta-carotene via activation of cAMP, PKA, CREB, and ERK1/2. Int J Cancer. 2006 doi: 10.1002/ijc.21537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jull BA, Plummer HK, 3rd, Schuller HM. Nicotinic receptor-mediated activation by the tobacco-specific nitrosamine NNK of a Raf-1/MAP kinase pathway, resulting in phosphorylation of c-myc in human small cell lung carcinoma cells and pulmonary neuroendocrine cells. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2001;127:707–717. doi: 10.1007/s004320100289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cattaneo MG, Codignola A, Vicentini LM, Clementi F, Sher E. Nicotine stimulates a serotonergic autocrine loop in human small-cell lung carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5566–5568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Codignola A, Tarroni P, Cattaneo MG, Vicentini LM, Clementi F, Sher E. Serotonin release and cell proliferation are under the control of alpha-bungarotoxin-sensitive nicotinic receptors in small-cell lung carcinoma cell lines. FEBS Lett. 1994;342:286–290. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80518-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heasley LE. Autocrine and paracrine signaling through neuropeptide receptors in human cancer. Oncogene. 2001;20:1563–1569. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shafer SH, Phelps SH, Williams CL. Reduced DNA synthesis and cell viability in small cell lung carcinoma by treatment with cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;56:1229–1236. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masuda A, Kondo M, Saito T, Yatabe Y, Kobayashi T, Okamoto M, et al. Establishment of human peripheral lung epithelial cell lines (HPL1) retaining differentiated characteristics and responsiveness to epidermal growth factor, hepatocyte growth factor, and transforming growth factor beta1. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4898–4904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petty WJ, Dragnev KH, Memoli VA, Ma Y, Desai NB, Biddle A, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibition represses cyclin D1 in aerodigestive tract cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7547–7554. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muller KM. Histological classification and histogenesis of lung cancer. Eur J Respir Dis. 1984;65:4–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Copin MC, Devisme L, Buisine MP, Marquette CH, Wurtz A, Aubert JP, et al. From normal respiratory mucosa to epidermoid carcinoma: expression of human mucin genes. Int J Cancer. 2000;86:162–168. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000415)86:2<162::aid-ijc3>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirsch L, Dantes A, Suh BS, Yoshida Y, Hosokawa K, Tajima K, et al. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors as anti-cancer drugs. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:981–988. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schuller HM, Porter B, Riechert A, Walker K, Schmoyer R. Neuroendocrine lung carcinogenesis in hamsters is inhibited by green tea or theophylline while the development of adenocarcinomas is promoted: implications for chemoprevention in smokers. Lung Cancer. 2004;45:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaplan JR, Manuck SB. Antiatherogenic effects of beta-adrenergic blocking agents: theoretical, experimental, and epidemiologic considerations. Am Heart J. 1994;128:1316–1328. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90254-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]