Abstract

This study examined both continuity and familial, intrapsychic, and environmental predictors of change in adolescent attachment security across a two-year period from mid- to late-adolescence. Assessments included the Adult Attachment Interview, observed mother-adolescent interactions, test-based data, and adolescent self-reports obtained from an ethnically and socio-economically diverse sample of moderately at-risk adolescents interviewed at ages 16 and 18. Substantial stability in security was identified. Beyond this stability, however, relative declines in attachment security were predicted by adolescents’ enmeshed, overpersonalizing behavior with their mothers, depressive symptoms, and poverty status. Results suggest that while security may trend upward for non-stressed adolescents, stressors that overwhelm the capacity for affect regulation and that are not easily assuaged by parents predict relative declines in security. over time.

Stability and Change in Attachment Security Across Adolescence

Given growing evidence of the importance of attachment security in adolescence and adulthood (Allen, Moore, Kuperminc, & Bell, 1998; Furman & Flanagan, 1997; Kobak, Sudler, & Gamble, 1991; van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 1996), one of the central questions in attachment research becomes understanding the sources of continuity and discontinuity in attachment security during this period. Bowlby (1980) describes the attachment system as being likely to display significant stability over time, but also as open to modification given certain types of environmental input. This study examined both continuity and predictors of change in levels of attachment security from mid- to late-adolescence.

Mid- to late-adolescence appears as a particularly important and promising time to examine continuities and predictors of change in attachment security. The cognitive and relational transformations of adolescence have the potential to significantly influence adolescents’ developing states of mind with respect to attachment, possibly leading to significant discontinuities over time in these states of mind (Allen & Land, 1999). In adolescence, only two preliminary, small-sample studies (e.g., each with fewer than 40 participants) with low-risk samples have assessed attachment stability in this period, reporting moderate stability from age 16 to 18 in a German sample (Zimmermann & Becker-Stoll, 2002), and from age 14 to 18 in an Italian sample (Ammaniti, Van IJzendoorn, Speranza, & Tambelli, 2000). Studies examining attachment stability are now clearly needed not only with larger samples, but also with the types of moderate-risk samples within which many of the links between attachment and functioning have been established.

Documenting the degree of actual continuity in attachment security across adolescence is only a first step in understanding the development of the attachment system during this period, however. Identifying predictors of future change in levels of attachment security is a critical next step toward building models explaining the linkages between adolescents’ psychosocial environments and their attachment security. Identifying predictors of change over time in attachment security plays a unique role in such model building: It can eliminate one of the major classes of confounding explanations for observed cross-sectional links between attachment and environmental factors--that these links may reflect the effect of security on the environmental factors rather than the reverse. Examining predictors of change thus provides one necessary (though not sufficient on its own) further step toward eliminating rival hypotheses to the important theoretical prediction that certain social-environmental factors are likely to causally influence attachment security over time.

This study examined the hypothesis that change in attachment security will be predicted by factors that affect adolescents’ capacity to develop their cognitive and emotional autonomy while maintaining key social relationships. Several researchers (Cummings & Davies, 1996; Kobak & Sceery, 1988) have posited that by adolescence, the attachment system can be productively viewed in part as an affect regulation system. The adolescent has an internal working model of self-in-relationship to others that guides both expectations and future behaviors in new situations so as to minimize distress and maximize felt security. These internal working models store and organize memories of past experiences and are thought to exist and operate largely at an automatic, preconscious level (Bowlby, 1980; Kobak & Sceery, 1988; Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985). Although these models are likely to be relatively stable, there are several circumstances under which they appear open to change as a result of experience.

First, as adolescents mature, they gain in autonomy, perspective-taking skills, and new relationship experiences, all of which provide opportunities to reconceptualize past attachment experiences (Allen & Land, 1999; Bowlby, 1988). In general, and absent major stressful experiences, the gradual increase in maturity and experience in new relationships that occurs during adolescence might be expected to produce a very gradual trend toward increasing security (as models become increasingly coherent and integrated) over time.

Bowlby (1973; 1980) also describes conditions under which the individual will begin to defensively exclude distressing information from awareness in ways that are likely to lead to the development of less secure working models of relationships over time. He notes that this is likely to occur when the individual is faced with experiences that arouse strong attachment needs that are not assuaged or that could create major conflicts with attachment figures. In particular, stressors that are uncontrollable are most likely to increase insecurity over time by challenging the attachment system with a stressor that cannot be readily managed by any response.

Stressors of sufficient magnitude to lead to increased insecurity appear particularly likely to occur around critical developmental tasks, where the stakes are highest for the individual. In early childhood, separation and parental rejection are primary issues around which stress may occur. In adolescence, threats to autonomy, relatedness and future competence as an adult are likely to present some of the strongest challenges to affect regulation systems (Allen & Hauser, 1996; Ryan & Deci, 2000). In contrast, external supports (e.g., from parents) might serve to buffer the effects of chronic negative stressors on the individual’s working models of attachment. This study examined a combination of relational, intrapsychic, and larger socio-environmental factors that are viewed as likely to predict future changes in security by creating or ameliorating stressful challenges to adolescents’ developing sense of autonomy and relatedness

Potential familial predictors of change in adolescent attachment security are suggested by cross-sectional findings of a link between security and signs that the adolescent is able to use the parent as a secure-base in daily interactions (Allen et al., 2003). The essence of this secure-base is that it allows the adolescent to autonomously explore emotional and cognitive independence within the context of a strong relationship with parents--an idea consistent with the definition of adult security as reflecting autonomy in thought together with valuing of attachment relationships (Main & Goldwyn, 1994). In adolescence, the parent-adolescent secure base appears to be specifically marked by a combination of mutual respect between parent and teen during disagreements, adolescent de-idealization of the parent, parental sensitivity, and parental supportiveness (Allen et al., 2003). These relationship characteristics may help the adolescent cognitively and emotionally step back and evaluate their relationship with parents while still remaining closely connected to them.

Conversely, enmeshed and overpersonalized parent-teen interactions that hinder the autonomy development process have been cross-sectionally linked to insecurity in attachment (Allen & Hauser, 1996; Dozier & Kobak, 1993). Such interactions present situations in which a fundamental developmental need, establishing autonomy, becomes in itself threatening to the quality of the parent-adolescent relationship. The “no-win” binds presented by such interaction styles (i.e., choosing between forsaking autonomy vs. threatening the relationship with the parent) may create stress and a sense of helplessness that overwhelms the attachment system and lead to defensive processing.

In addition to relational stressors, intrapsychic stressors may play an important role in the development of an adolescent’s attachment system. Depressive symptoms, with the hopelessness and despair that they embody, almost by definition overwhelm the individual’s affect regulation system and may thus lead to less adaptive forms of defensive processing. Indeed, Bowlby (1980) has described the process of functional breakdown of the attachment system in the face of uncontrollable aversive stressors as in many ways parallel to Seligman’s (1979) description of learned helplessness in depression. Depressive symptoms also create intense distress and correspondingly strong arousal of attachment needs, which not only aren’t easily assuaged by attachment figures, but which may lead to conflict with them (Daley & Hammen, 2002). These are precisely the conditions Bowlby (1980) has described as likely to lead to increased defensive processing and insecurity. Depressive symptoms have been cross-sectionally linked to attachment insecurity in adolescence and to inability to form secure relationships with one’s infant offspring as a parent (Allen, Moore et al., 1998; Cole-Detke & Kobak, 1996; Kobak et al., 1991; Radke-Yarrow, Cummings, Kuczynski, & Chapman, 1985), but have never been examined as possible predictors of the future development of more insecure states of mind regarding attachment.

Stressors within the broader psychosocial environment have also been frequently associated with attachment insecurity (Easterbrooks & Graham, 1999; van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 1996). Financial hardship, in particular, may reduce the capacity of the family system to respond to numerous stressors (e.g., to serve as a secure base for the adolescent), at the same time increasing the likelihood that such stressors will occur in the first place (Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz, & Simons, 1994; McElhaney & Allen, 2001; McLoyd, Jayaratne, Ceballo, & Borquez, 1994; Sampson & Laub, 1994). Such hardship has been shown to be a chronic irritant that substantially increases the frequency of stressful, aversive, and hostile interactions between family members (Conger et al., 1994). Because financial hardship typically affects both parents and adolescents, it may well leave the adolescent increasingly in need of support and comfort from primary attachment figures at a time when these figures are most stressed and least able to provide this support (Simons, Lorenz, Wu, & Conger, 1993). Again, this is almost exactly the situation that Bowlby (1980) describes as likely to lead to insecurity.

Finally, given intense interest in the intergenerational transmission of attachment patterns beyond childhood (Benoit & Parker, 1994), current maternal attachment status appears as a natural potential predictor of changing levels of adolescent attachment security. The little research that has been conducted thus far suggests that maternal attachment status is only weakly related to offspring attachment status by mid- to late-adolescence, and that such relations tend to be mediated via current qualities of parent-adolescent interactions (Allen et al., 2003). However, this research does not rule out the possibility that maternal attachment status may alter future patterns of family interaction over the course of adolescence, and thus predict the future development of adolescent security over time, regardless of its concurrent associations with adolescent security.

This study examined both levels of continuity and predictors of change over time in adolescent attachment security within an ethnically and socio-economically diverse sample of moderately at-risk adolescents, followed over a two-year period from mid- to late-adolescence. The sample was selected to allow assessments within a maximally meaningful range of psychosocial and family functioning, including adolescents and families functioning both adequately and poorly. The sample was thus designed to be consistent with the types of samples used in much of the basic attachment theory validation data linking security to psychosocial functioning.

After examining the stability of attachment security, this study independently assessed each of the specific classes of predictors identified above (family interaction characteristics, depressive symptoms, poverty status, and maternal attachment security) for their capacity to predict changes over time in levels of adolescent security relative to baseline levels of security. Finally, in an effort to begin to build a model of conjoint operation of the multiple potential predictors of changing attachment security in adolescence, this study examined the extent to which any identified predictors of changing levels of adolescent attachment security were redundant with one another vs. additive in their capacity to predict changing levels of security.

Method

Participants

Data were collected from 101 adolescents (49 male and 52 female) first interviewed in the ninth and tenth grade along with their mothers, and re-interviewed approximately two years later. These adolescents were a subset of 127 adolescents for whom attachment data were originally collected at baseline, 26 of whom did not complete a second attachment interview. Demographic data are presented for participants who were able to complete baseline and follow-up interviews. The mean ages of the adolescents at the two assessments were 15.9 years (s.d.= 0.8), and 18.1 years (s.d.=1.0), respectively. This adolescent sample was 64% European-American, 34% African-American, and 2% with other or unspecified backgrounds. Thirty percent of adolescents were living with both biological parents. The median family income was $25,000 (range was from less than $5,000 to greater than $60,000), and parents' median education level was a high school diploma with some training post high school, with a range from less than an eighth grade education to completion of an advanced degree.

Attrition analyses revealed that the subset of adolescents with attachment data available longitudinally did not differ from the larger sample on any of the demographic or substantive measures in this study, with the exception of overpersonalizing behavior in interactions with mothers, in which adolescents who did not receive the attachment interview at Time 2 had higher levels of overpersonalizing behavior at Time 1 than those who completed the Time 2 attachment interview.

Adolescents were recruited through public school systems serving rural, suburban and moderately urban populations. Ninth and tenth graders were selected for inclusion in the study based upon the presence of any of four possible academic risk factors, including failing a single course for a single marking period, any lifetime history of grade retention, 10 or more absences in one marking period, and any history of school suspension. These broad selection criteria were established to sample a sizeable range of adolescents who could be identified from academic records as having the potential for future social difficulties, including both adolescents already experiencing serious difficulties and those who are performing adequately with only occasional, minor problems. As intended, these very broad criteria identified approximately one-half of all 9th and 10th grade students who had at least one risk factor and were thus considered eligible for the study.

Procedure

After adolescents who met study criteria were identified, letters were sent to each family of a potential participant explaining the investigation as an ongoing study of the lives of teens and families. These initial explanatory letters were then followed by phone calls to families who indicated a willingness to be further contacted. If both the teen and the parent(s) agreed to participate in the study, the family was scheduled to come to our offices for two, three-hour sessions at each wave of the study. Adolescents and families were paid for participation at each interview. At each session, active, informed consent was obtained from parents and teens. In the initial introduction and throughout both sessions, confidentiality was assured to all family members, and adolescents were told that their parents would not be informed of any of the answers they provided. Participants’ data were protected by a Confidentiality Certificate issued by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which protected information from subpoena by federal, state, and local courts. Transportation and childcare were provided if necessary.

Attachment interviews were administered to adolescents at both the initial wave of data collection and at a follow-up wave of assessment two years after the initial interview, and, at just the initial wave of data collection, to mothers of these adolescents’ . All other assessments reported below are from the initial wave of data collection so as to focus on prospective predictors of changing levels of attachment security.

Measures

Adult Attachment Interview and Q-set (George, Kaplan, & Main, 1996; Kobak, Cole, Ferenz-Gillies, Fleming, & Gamble, 1993)

This structured interview probes individuals' descriptions of their childhood relationships with parents in both abstract terms and with requests for specific supporting memories. For example, subjects were asked to list five words describing their early childhood relationships with each parent, and then to describe specific episodes that reflected those words. Other questions focused upon specific instances of upset, separation, loss, trauma, and rejection. Finally, the interviewer asked participants to provide more integrative descriptions of changes in relationships with parents and the current state of those relationships. The interview consisted of 18 questions and lasted one hour on average. Slight adaptations to the adult version were made to make the questions more natural and easily understood for an adolescent population (Ward & Carlson, 1995). Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed for coding.

The AAI Q-set (Kobak et al., 1993) was designed to closely parallel the Adult Attachment Interview Classification System (Main & Goldwyn, 1998), but to yield continuous measures of qualities of attachment organization. Each rater read a transcript and provided a Q-sort description by assigning 100 items into nine categories ranging from most to least characteristic of the interview, using a forced distribution. All interviews were blindly rated by at least two raters with extensive training in both the Q-sort and the Adult Attachment Interview Classification System.

These Q-sorts were then compared with a dimensional prototype sort for secure vs. anxious interview strategies, with security reflecting the overall degree of coherence of discourse, the integration of episodic and semantic attachment memories, and a clear objective valuing of attachment. The individual correlation of the 100 items of an individual's Q-sort with a prototype sort for a maximally secure transcript was then used as that participant's security score (ranging from −1.00 to 1.00, with higher scores denoting greater security). The Spearman-Brown interrater reliabilities for the final security scale score were .84 and .85 for adolescents and their mothers respectively at Wave 1 and .88 for adolescents at Wave 2. Coding differences were resolved by averaging coders’ scores. Although this system was designed to yield continuous measures of qualities of attachment organization, rather than to replicate classifications from the Main & Goldwyn (1998) system, we also compared the adolescent scores we obtained at Time 1 to a subsample (N = 76) of adolescent AAI's that were classified by an independent coder with well-established reliability in classifying AAI's (U. Wartner). We did this by converting the Q-sort scales described above into classifications using an algorithm described by Kobak (1993). Using this approach, we obtained an 84% match for security vs. insecurity between the Q-sort method and the classification method (kappa = .68). Continuous measures of security were used in all analyses.

Autonomy and relatedness in disagreements

Adolescents and their mothers participated in a revealed differences task in which they discussed a family issue about which they disagreed. Typical topics of discussion included money (19%), grades (19%), household rules (17%), friends (14%), and brothers and sisters (10%); other possible areas included communication, plans for the future, alcohol and drugs, religion, and dating. These interactions were videotaped, and then transcribed.

Both the videotapes and transcripts were utilized to code the mother-adolescent interactions for behaviors exhibiting autonomy using the Autonomy and Relatedness Coding System (Allen, Hauser, Bell, McElhaney, & Tate, 1998). Concrete behavioral guidelines were utilized to code both mothers’ and adolescents’ individual speeches on one or more of 10 subscales. This study assessed the three scales derived from this system that have been previously linked to attachment security. The Dyadic Relatedness scale captures validating statements and displays of engagement and empathy with the other party and their statements. Behaviors are initially coded separately for mothers’ and adolescents’ and then combined (after standardizing) to yield a measure of dyadic relatedness, which has been found to be a cross-sectional correlate of adolescent security in this sample (Allen et al., 2003). Overpersonalizing behaviors reflected the extent to which an adolescent focused their arguments away from reasons underlying their position, and toward the personal characteristics of themselves or their mothers. These have been previously found to be predictive of future levels of passivity of thought processes, which is one marker of attachment insecurity (Allen & Hauser, 1996). Recanting behaviors reflected the extent to which an adolescent rapidly backed away from a disagreement without appearing to have been persuaded by his or her mother’s reasoning. This is also viewed as a measure of struggles with autonomy processes and has been related to passivity of thought processes in the Adult Attachment Interview (Allen & Hauser, 1996). Two trained coders coded each interaction and their codes were then summed and averaged. Inter-rater reliability was calculated using intraclass correlation coefficients as r’s = .86, .84, and .62 for dyadic displays of positive relatedness, adolescent overpersonalizing, and recanting behavior respectively, the first two of which are considered in the “excellent” range and the third of which is considered in the “good” range for this coefficient (Cicchetti & Sparrow, 1981).

Maternal attunement to adolescent self-perceptions

This measure assessed how well mothers’ understood their adolescents’ self-perceptions by asking them to estimate their adolescents’ actual responses to a widely used self-perception profile (Allen et al., 2003). Adolescents first completed 8 of the 9 scales (40 items) of the 45-item Adolescent Self-Perception Profile (Harter, 1988) (the job competence scale was omitted). For each item, two sentence-stems are presented side by side, for example: “Some teenagers find it hard to make friends,” but “For other teenagers it's pretty easy.” Adolescents were asked to decide which stem best described them and whether the statement was “sort of true” or “really true” for them. Mothers were then instructed to complete the exact same measure of Adolescent Self-Perceptions as closely as possible to how they thought their teen would fill out the measure, as a marker of the accuracy of their understanding of their teens’ likely reported self-perceptions. For each item, the absolute magnitude of mothers’ errors in their predictions of their adolescents’ responses was tallied (ranging from 0 to 3 points of error for each item). These errors were then summed and averaged to yield an average error score. We then reverse scored this average error score (by subtracting it from 3) to yield a measure of maternal attunement to adolescent self-perceptions, which has been previously found to be cross-sectionally linked to adolescent attachment security in this sample (Allen et al., 2003). The mean score for attunement, 2.18 (out of a possible 3), thus indicates that on average, mothers mis-estimated their teens’ scores by 0.82 points (out of a 3 point possible range of error). This attunement measure displayed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .83).

Adolescent deidealization of mother

Deidealization was assessed using the Mother-Father-Peer Scale (Epstein, 1983). This measure uses 5-point Likert items to assess perceived qualities of the adolescent’s relationship with mother, father, and peers. This study used scales from this instrument with respect to the relationship with mother. Deidealization was assessed from 7 items assessing presence or absence of unrealistically positive views of the childhood relationship with mother. Participants indicated the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with statements such as “When I was a child, my mother was an ideal person in every way.” These items were then summed (with stronger disagreement with idealized statements receiving higher scores) and averaged to yield a measure of adolescent deidealization of their mothers. Internal consistency for this measure was high (Cronbach’s α = .82).

Maternal supportiveness

This measure was obtained by standardizing and averaging scales from two measures that tap related aspects of the overall quality of the mother-adolescent relationship. The Mother-Father-Peer Scale (Epstein, 1983) uses ten items similar in format to those described above to assess maternal acceptance (e.g., “When I was a child, my mother gave me the feeling that she liked me as I was; she didn’t feel she had to make me over into someone else.”). Two scales from the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987) were used to assess adolescents' perceptions of the quality of communication and trust in their relationship with their mothers, each of which was assessed with eight 5-point Likert items. In spite of its title, this measure is not considered a proxy for security of attachment organization, and displays only a very weak relationship to other indices of attachment organization when considered in isolation (Crowell, Treboux, & Waters, 1993). The internal consistency of the sum of these three scales (acceptance, communication and trust) was high (Cronbach’s alpha = .87).

Depressive symptoms

Adolescents reported the degree of their depressive symptoms using the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck & Steer, 1987). This well-validated, 21-item inventory has been positively correlated with poor self-esteem, hopelessness, and negative cognitive attributions. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.84.

Family poverty status

Poverty status was assessed in terms of whether families reported income fell at or below 200% of the Federal poverty line (as determined by the Federal income-to-needs ratio that compares household income with number of persons in the household supported by this income). The 200% cut-off was chosen on the basis of past research on the effects of poverty that find significant effects on adolescent development when income falls below this level (Conger, Conger, & Elder, 1997; Hauser & Sweeney, 1997; Teachman, Paasch, Day, & Carver, 1997).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Means and standard deviations for all substantive variables are presented in Table 1. Initial analyses examined the role of gender, and racial/ethnic minority status as possible predictors of change in attachment security. Gender was unrelated to adolescents’ attachment security at either time point. Racial/ethnic minority status was linked to security at both time points, but was not predictive of change over time in security. No moderating effects of either of these demographic factors on the relationships examined in the primary analyses below were found, nor were any 3-way interactions found of minority status, gender and specific predictors in this study.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Attachment and Predictor Variables

| Mean

|

SD

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Attachment Security Age 16 (I) | .26 | .39 |

| Adolescent Attachment Security Age 18 (I) | .22 | .40 |

| Maternal Attachment Security (I) | .28 | .37 |

| Maternal Attunement to Teen (T) | −.80 | .27 |

| Maternal Supportiveness (A) | .16 | 2.64 |

| Dyadic Relatedness (O) | −.04 | 1.78 |

| Overpersonalizing Behavior | .70 | .87 |

| Recanting of Positions | 1.01 | .80 |

| Adolescent Deidealization (A) | 21.89 | 5.72 |

| Depressive Symptoms (A) | 8.88 | 9.03 |

| N / % | N / % | |

| Family Poverty Status | Below 200% of Pov. Line: | Above 200% of Pov. Line: |

| 41 / 40.6% | 60 / 59.4% |

Note: I – Coded from Interviews; T- Assessed via Test; A- Adolescent-reported; O – Observed;

Primary Analyses

Stability of attachment security over time in adolescence?

The overall level of attachment security in the sample as a whole did not change significantly over this two-year period, as indicated by the mean levels of security in Table 1, although considerable variability existed in levels of security for individual adolescents over time. For descriptive purposes, Table 2 presents the results of simple univariate correlations among the key variables of interest, including attachment security as assessed at each time point. Notably, there are numerous correlations with adolescent attachment security at various times, and significant stability (r = .61, p < .001) in attachment security over time. There were no moderating effects of adolescents’ gender, racial/ethnic minority status, or family income on this stability.

Table 2.

Univariate Correlations Between Attachment and Predictor Variables

| Teen Security 16 | Teen Security 18 | Maternal Security | Maternal Attunement | Maternal Supportiveess | Dyadic Relatedness | Over- personalizing Behavior | Recanting | Deideal- ization | Depressive Symptoms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teen Security (16) | --- | |||||||||

| Teen Security (18) | .61*** | --- | ||||||||

| Maternal Security | .27** | .19+ | --- | |||||||

| Maternal Attunement | .37*** | .32** | .05 | --- | ||||||

| Maternal Supportiveness | .32** | .38*** | .04 | .08 | --- | |||||

| Dyadic Relatedness | .46*** | .40*** | .34*** | .25* | .25 | --- | ||||

| Overpersonalizing Behavior | .09 | −.12 | .08 | −.01 | −.14 | −.01 | --- | |||

| Recanting of Positions | .13 | .00 | −.01 | .04 | .19+ | .15 | .12 | --- | ||

| Deidealization | .09 | .24* | .16 | −.06 | .60*** | .09 | −.09 | .22* | --- | |

| Depressive Symptoms | −.11 | −.31** | −.15 | −.02 | −.38*** | −.18+ | .02 | .13 | −.16 | --- |

| Poverty Status | −.25* | −.32** | −.21* | −.19+ | −.18+ | −.22* | −.27** | −.07 | .07 | .13 |

Note: p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

p < .10

Predictions from observed displays of autonomy and relatedness in family interactions

The remaining primary hypotheses of this study were addressed with a hierarchical regression strategy in which attachment security at age 18 was the dependent variable, and attachment security at age 16 was consistently entered as the first predictor, followed by other predictors of interest. This approach of predicting a future level of a variable while accounting for predictions from initial levels (e.g., accounting for stability) yields one marker of change in that variable: increases or decreases in its final state relative to predictions based upon initial levels (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). Different classes of predictors (e.g., family factors, depressive symptoms, etc.) were each examined separately so that relations to future security would not be obscured by confounds with other classes of predictors. To reduce the likelihood of Type I error, variables representing similar constructs were examined in blocks as predictors for each substantive question of interest below. Only if an overall block of similar variables was found to be predictive of future attachment security were individual variables then examined.

These analyses began by examining predictions of changes in levels of attachment security from age 16 to age 18 from three observational measures of qualities of autonomy and relatedness in adolescents’ interactions with their mothers around a disagreement at age 16 that have been previously linked to security cross-sectionally. These include: overall dyadic efforts at maintaining the relationship; overpersonalizing behavior on the part of the adolescent; and the adolescents’ recantation of their position without having been persuaded by the mother’s reasoning. Results are presented in Table 3, and indicate that adolescents’ who overpersonalized disagreements with their mothers had relatively lower levels of attachment security two years later, even after accounting for baseline levels of security. A trend level finding was also obtained suggesting that overall levels of dyadic relatedness in mother-adolescent discussions at age 16 predicted higher levels of future attachment security, after accounting for baseline levels of security.

Predictions from self-report and test-based measures of mother-teen relationships

Analyses next examined predictions of changes in levels of attachment security from age 16 to age 18 from three self-report and test-based measures that had been previously related to attachment security: adolescents’ reports of the quality of the mother-adolescent relationship, maternal attunement to the adolescent, and adolescent’s de-idealization of mother. Results are presented in Table 4, and indicate that only the overall quality of reported maternal supportiveness added to the prediction of attachment security at age 18 after accounting for levels of security age 16. This indicates that adolescents who reported that their mothers were more supportive at age 16 displayed relatively higher levels of security at age 18, even after accounting for baseline levels of security at 16.

Predictions from adolescent depressive symptoms

Analyses next examined predictions of changes in levels of attachment security from age 16 to age 18 from adolescents’ reported levels of depressive symptoms at age 16. Results indicate that even after accounting for the baseline effects of security at age 16, adolescents’ depressive symptoms at age 16 were predictive of relatively lower levels of security at age 18 (βdepression = −.25, p = .002, Partial R2 = .06, Total R2 = .43).

Predictions from family poverty status

Analyses next examined predictions of changes in levels of attachment security from age 16 to age 18 from family poverty status at age 16. Results indicate that even after accounting for the baseline effects of security at age 16, poverty status at age 16 was a significant predictor of relatively lower levels of security at age 18 (βpoverty = −.18, p = .03, Partial R2 = .03, Total R2 = .40).

Redundant vs. unique nature of predictors of changing attachment security

This question was addressed with hierarchical regression analyses to examine the extent to which the different predictors of relative changes in levels of attachment security identified above contributed unique vs. redundant variance to explaining these changes over a two-year period, and also to provide an estimate of the percentage of the total variance in change in attachment security that could be explained by these factors. Predictors were entered in order ranging from those least proximal to the current attachment relationships of the adolescent to those most proximal to these relationships. This approach provides the strictest test of the explanatory power of the more proximal family and individual factors that have been most closely theoretically tied to attachment security.

Thus, family poverty was entered first as a predictor, followed by levels of adolescent depressive symptoms, followed by a block of the three previously identified mother-adolescent relationship markers of security. These results, presented in Table 5, show that poverty status, adolescent depressive symptoms at age 16, and adolescents’ behavior overpersonalizing discussions each contributed significantly to explaining future levels of attachment security, even after accounting for baseline levels of security. In total, age 16 security accounted for 37% of the variance in security at age 18 (the stability factor), and the identified predictors accounted for an additional 15% of the variance in age 18 security. Overall, substantial variance in age 18 attachment security was predictable at age 16 (Multiple R = .72).

Table 5.

Predicting Attachment Security at Age 18 from Security, Poverty Status, Depression, and Family Interaction Qualities at Age 16

| β | ΔR2 | Total R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step I. | |||

| Security (Age 16) | .61*** | .37*** | .37*** |

| Step II. | |||

| Poverty Status (Age 16) | −.18* | .04* | .41*** |

| Step III. | |||

| Adolescent Depressive Symptoms (Age 16) | −.23** | .05** | .46*** |

| Step IV. | |||

| Dyadic Relatedness (Age 16) | .01 | ||

| Overpersonalizing Discussions (Age 16) | −.20** | ||

| Maternal Supportiveness (Age 16) | .16+ | ||

| Statistics for Step | .06** | .52*** | |

Note. p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05

p < .10.

weights are from variable’s entry into model.

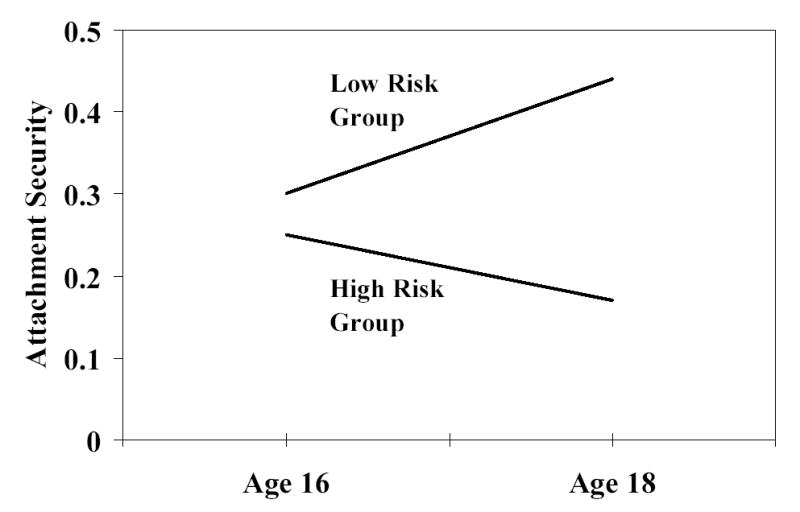

Post-hoc analyses: Overall patterns of change in security for youths with differing risk profiles

given the findings above, and more general interest in the question about how levels of attachment security might change across the lifespan, we next re-examined change from age 16 to age 18 in absolute levels of security by comparing youth who did vs. did not experience any of the risk factors identified in the final model above. To do this, we split our sample into two groups. One low-risk group consisted of youth who were not living in poverty and whose scores on measures of depression and overpersonalizing behavior were below the mean for the sample on those measures. Although this group was somewhat unusual relative to this overall moderate-risk sample (N= 20), it was deemed likely to represent a fairly normative, low-risk sample within the general population. A second, higher-risk group consisted of youths who were either in poverty or had scores above the mean on depression or overpersonalizing interactive behaviors (N=81). Figure 1 depicts the change in mean security scores for each of the two groups from age 16 to age 18. The higher-risk group significantly declined in levels of security from age 16 to age 18 (Mean (Age 16) = 0.25; Mean (Age 18) = 0.17 T (1,80) = 2.22, p = .03). The lower risk group, in contrast, displayed an equally large increase in levels of security over this same age span, though with a much smaller sample this increase displayed only trend level significance (Mean (Age 16) =0.30; Mean (Age 18) = 0.44 T (1,19) = 1.92 p =.07).

Figure 1.

Changing levels of security for youth with vs. without identified risk factors.

We also examined whether baseline levels of security might interact with any of the risk factors examined in predicting future levels of security, but no such interactions were obtained.

Finally, although adolescents’ racial/ethnic minority status was not related to change in attachment security over time, given that it was related to attachment at individual assessment points and was found to be related to one of the final predictors of this change (poverty status, r = .44, p < .001), extended analyses explored whether inclusion of the effects of minority status would have altered findings regarding poverty status reported. No significant changes in results were obtained when minority status was entered into predictive models either as a covariate or in interactions with adolescent family poverty status. Minority group membership was also not related to any of the other significant predictors of change in attachment security in the final model presented in Table 5.

Discussion

This study examined changes in adolescents’ attachment security over a two-year period, from age 16 to age 18. The picture that emerged was one of both significant stability but also of predictable changes in security over time. Across the sample as a whole, there were no net increases or decreases in levels of security during this period and individual levels of attachment security also displayed a moderate to high degree of continuity. Continuities were far from perfect, however. When discontinuities in individual adolescents’ levels of security occurred, future levels of attachment security were predicted (after accounting for baseline levels) by factors that stressed or supported adolescents’ capacities for affect regulation and for developing autonomy and relatedness in primary relationships. These predictions thus complement and qualify the initial global findings of little change in attachment security. Post-hoc analyses suggested that for individuals with one or more identified intrapsychic, familial, or environmental major stressors, significant declines in security occurred over the course of adolescence, whereas individuals with no risk factors at age 16 trended toward increasing security over the following two years. Taken together, these data provide the first available evidence regarding factors that might begin to explain processes of stability and change in individual differences in the organization of the attachment system across adolescence. Each of these findings is discussed in turn below, followed by consideration of the limitations of these data.

The initial finding that overall levels of security in the Adult Attachment Interview displayed substantial stability over a two-year period suggests that the internal organization of an individual’s state of mind regarding attachment has to some degree stabilized by mid-adolescence, even in an at-risk sample. The levels of stability achieved in the AAI (r = .61) over time in this study are comparable to the Kappa’s of .63 to .70 reported in longer term studies of attachment stability in adulthood (Benoit & Parker, 1994; Crowell, Treboux, & Waters, 2002).

The findings of significant overall stability in attachment security in this study do not, however, in any way mean that the attachment system has become impervious to change during adolescence. On the contrary, this study identified several constructs that reliably predicted changes in security over time. Several family relationship qualities were identified that predicted future levels of security even after accounting for initial levels of security. Adolescents who perceived their mothers as being more supportive during disagreements made relative gains in security over the following two years. Conversely, adolescents who at age 16 were observed to be caught up in overpersonalized, enmeshed discussions of disagreements with their mothers had relatively lower levels of security two years later, even after accounting for baseline levels of security and predictions from non-familial stressors. As in other attachment and family interaction studies of enmeshed and overpersonalizing behavior, the key element was the adolescent’s behavior, not the mother’s (Allen & Hauser, 1996). One explanation is that adolescents who engage in these strategies are struggling with autonomy issues in a highly confused way that is likely to leave them mentally and emotionally entangled in their relationships with their mothers. Such mental entanglement during a developmental period characterized by the need to establish autonomy seems likely to produce enormous emotional stress that obviously cannot be easily assuaged by parents (given their role in producing the stress). This unassuaged stress also seems unlikely to leave the adolescent positioned to engage in the thoughtful and balanced re-evaluation of parental relationships that is characteristic of secure/autonomous adults (Main & Goldwyn, 1994).

Although even longitudinal change studies cannot establish causal relationships, the focus of this study on identifying predictors of future attachment security after accounting for baseline levels of security is important, because it eliminates one set of potential causal pathways explaining the links between the predictors and security. For example, prior research has shown that family interaction patterns are linked to security in adolescence (Allen & Hauser, 1996; Allen et al., 2003; Dozier & Kobak, 1993). But one plausible explanation for these findings that could not be ruled out with cross-sectional data was that family interactions might simply reflect the adolescent’s current attachment state of mind (e.g, more secure adolescents might tend to perceive their mothers as being more supportive, in part because they were more secure and hence able to recognize their mothers’ support). The findings of this study, that low levels of overpersonalizing behavior in arguments and high levels of maternal support were predictive of future levels of security after accounting for current levels, makes it unlikely that these links simply reflect a past or concurrent influence of security on these behaviors. Although these findings clearly stop short of establishing that overpersonalizing behavior directly influences security, they do move beyond one of the major classes of confounding explanations for the link between such behavior and security.

In contrast, several other family measures that previously had been linked to security (e.g., adolescent’s de-idealization of their mothers, and maternal attunement to their adolescents) were not predictive of changes in relative levels of security in this study. It is possible that the previously observed cross-sectional relations between security and these family characteristics may have simply been due to the effects of security on these family behaviors, rather than the effects of these specific family behaviors on security. It should also be noted that maternal attachment security was not predictive of changing levels of adolescent security, consistent with prior findings suggesting that any effects of maternal attachment security are likely to be mediated via family interaction patterns (Allen et al., 2003).

Adolescent’s depressive symptoms were also found to predict relative decreases in levels of security over a two-year period. One explanation for this finding is that the strain of depression may create a stressor of such magnitude and persistence that it cannot be fully assuaged by attachment figures. Depression may thus overwhelm the adolescent emotionally and lead to more defensive coping and to insecurity (Bowlby, 1980). In addition, the impact of depression on close relationships is well documented (Hammen, 2000). It may be that the tension that is frequently characteristic of depressed individuals’ relationships may serve to confuse and overwhelm the adolescent at precisely those times when a clearer pattern of individuation from parents is most needed.

Poverty status in adolescence also appeared as a predictor of relative decreases in security, a finding consistent with its long-identified role as a risk factor likely to impinge on child and adolescent development within the family (Conger et al., 1994; McLoyd et al., 1994; Sampson & Laub, 1994). Stressors associated with poverty, ranging from frequent residence changes, to untreated medical problems, to lack of basic resources, all appear likely to severely challenge the adolescents’ affect regulation capacities while undermining parents’ capacity to provide support and comfort (Conger et al., 1994). Alternatively, the additional exposure to risks associated with poverty (e.g., high crime neighborhoods) may undermine autonomy-gaining processes within the family (McElhaney & Allen, 2001). This in turn may make it more difficult for an adolescent to develop a secure/autonomous stance with respect to attachment relationships.

Perhaps the most striking finding of this study was that poverty, depression, and overpersonalizing family interactions combined additively to predict future levels of attachment security, even after accounting for the substantial stability in this measure over a two-year period. All told, this combination of factors accounted for 15% of the variance in adolescent security at age 18, over and above the 37% of this variance that was already accounted for by prior levels of security. The resulting 52% of the variance in future attachment security that could be accounted for (Multiple R = .72) is strikingly close to the theoretical upper bound on predictions in security that is obtainable given the limits in the reliability (interrater r’s = .84 to .88 for adolescent security) of coding of this measure. Although these data are non-experimental, they raise the possibility that attachment security in mid-adolescence may be both relatively stable and also susceptible to change in systematic fashion from theoretically-related factors in the adolescent’s psychosocial environment.

It is noteworthy that the major classes of predictors of attachment security examined (familial, intrapsychic, and socioeconomic) each independently contributed to predictions of future security, suggesting that each in some way captured a unique facet of what is needed to understand future levels of security. What appears to tie these seemingly diverse predictors together is that each identified stressor has the potential to both emotionally overwhelm the adolescent while leaving them relatively unable to get support from attachment figures. Each does this in a different way, which may explain their unique predictions to future levels of attachment security. Enmeshed and overpersonalized family interactions create stress by threatening developing adolescent autonomy, but by their very nature they also make it difficult for parents to assuage this stress (as it’s the lack of autonomy from parents that is creating it). Similarly, depressive symptoms typically embody a sense of personal helplessness and convey great distress that also tend to undermine close relationships (Daley & Hammen, 2002; Hammen, Shih, Altman, & Brennan, 2003), as does poverty, albeit via different mechanisms (Conger et al., 1994). In short, when adolescents’, for whatever reason, no longer have a truly functional secure base relationship with a caregiver capable of helping them cope with stressors they face, then they appear at risk for decreasing attachment security over time.

From this perspective, the overall finding of no mean change in levels of security for the sample as a whole appears likely to be misleading. Given the findings discussed above, one may reasonably postulate several different pathways in the development of attachment representations within the sample over the course of adolescence (Sroufe, 1997). Adolescents who have relatively unproblematic family interactions, who are not depressed, and who are not living in poverty, appear to trend toward establishing greater cognitive and emotional autonomy in the context of valuing of attachment relationships--that is, they become more secure, as security is defined in adulthood (Main & Goldwyn, 1994). This would be consistent with the expectation that the cognitive gains and increasing emotional autonomy vis a vis parents that comes in late adolescence are likely to give the adolescent the chance to form increasingly coherent models of attachment relationships and increase their overall capacity to think autonomously about such relationships while still valuing them (Kobak & Cole, 1994). Alternatively, in keeping with findings of prior research on attachment stability at other points in the lifespan (Easterbrooks, Davidson, & Chazan, 1993; Easterbrooks & Graham, 1999; van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 1996; Vaughn, Egeland, Sroufe, & Waters, 1979; Weinfield, Sroufe, & Egeland, 2000), it appears that the presence of significant psychosocial stressors that influence adolescents’ developing autonomy may be sufficient to not only impair the development of increasing security/autonomy in attachment states of mind, but to actually undermine levels of security over the following years.

Although this study advances our understanding of the relation of both continuities and predictors of change in attachment security over the course of adolescence utilizing multiple methods and longitudinal data, there are nonetheless a number of limitations to these findings that bear consideration. First, this study sought to assess predictors of continuity and discontinuity in a moderately at-risk sample, for whom differences in levels of security and individual and family functioning would be most likely to be meaningful. Although this moderate risk sample parallels the types of samples in which many of the strongest relationships of attachment to psychosocial functioning have been previously reported, it should also be clear that the present results cannot be generalized to other populations without further replication.

Second, in this study there was a relation between adolescents’ racial/ethnic minority group membership and their attachment security that might have potentially confounded results, particularly given that minority group membership was also associated with one predictor--family poverty status. However, when analyses included minority group membership as either a covariate or moderating variable, it did not have any direct effect nor did it alter the effect of poverty status as a predictor of change in attachment security, thus indicating that the models presented in results did not differ significantly depending on youth’s racial/ethnic status. Finally, minority group status was not related to change in attachment security over time. The current results are thus consistent with the interpretation that adolescents’ minority group membership was not linked, directly or indirectly, to change in attachment security, although further research with samples that disentangled minority group membership from poverty status would be needed to clarify this issue further.

Third, to the extent that adolescent security is derived from experiences in multiple attachment relationships, understanding the role of other such relationships, such as the paternal relationship—which several studies suggest becomes increasingly important in adolescence (Phares, 1992; Phares & Compas, 1992)—will be important for future research to explore. Third, this study does not address the question of how the identified predictors may have led to changes in attachment security, whether via increases in adolescents’ defensive processing, as Bowlby has suggested, or via some other mechanisms. Finally, the Q-sort attachment methodology employed in this study, though strongly empirically linked to classifications using the Adult Attachment Interview Classification System, did not allow assessment of insecure/unresolved classifications. This does not invalidate the present findings, as unresolved attachment organization is a superordinate classification that coexists with an otherwise secure, dismissing, or preoccupied overall attachment organization. Similarly, this study focused upon overall security/insecurity, rather than specific insecure/dismissing or insecure/preoccupied manifestations of insecurity, in part as a result of sample size limitations. Future studies, particularly those with larger samples, might productively explore the role of these additional aspects of attachment organization in terms of its manifestations within the parent-adolescent relationship.

Table 3.

Predicting Adolescent Attachment Security at Age 18 from Security and Observed Family Interactions at Age 16

| β | ΔR2 | Total R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step I. | |||

| Security (Age 16) | .61*** | .37*** | .37*** |

| Step II. | |||

| Dyadic Relatedness (Age 16) | .15+ | ||

| Overpersonalizing Discussions (Age 16) | −.17* | ||

| Recanting Position (Age 16) | −.08 | ||

| Statistics for Step | .06*** | .43*** | |

Note. p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05

p < .10.

weights are from variable’s entry into model.

Table 4.

Predicting Attachment Security at Age 18 from Security and Self-Reports Regarding Family Relationships at Age 16

| β | ΔR2 | Total R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step I. | |||

| Security (Age 16) | .62*** | .39*** | .39*** |

| Step II. | |||

| Maternal Supportiveness (Age 16) | .25** | ||

| Maternal Attunement (Age 16) | .08 | ||

| De-idealization (Age 16) | −.13 | ||

| Statistics for Step | .05* | .44*** | |

Note. p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05

p < .10.

weights are from variable’s entry into model.

Acknowledgments

This study and its write-up were supported by grants from the William T. Grant Foundation and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH44934 & R01-MH58066). Correspondence concerning this study should be sent to the first author at Department of Psychology, University of Virginia, Box 400400, Charlottesville, VA 22904-4400 (Email: allen@virginia.edu).

Contributor Information

Joseph P. Allen, University of Virginia

Kathleen Boykin McElhaney, Davidson College.

Gabriel P. Kuperminc, Georgia State University

Kathleen M. Jodl, University of Michigan

References

- Allen JP, Hauser ST. Autonomy and relatedness in adolescent-family interactions as predictors of young adults' states of mind regarding attachment. Development & Psychopathology. 1996;8(4):793–809. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Hauser ST, Bell KL, McElhaney KB, Tate DC. University of Virginia; Charlottesville, VA: 1998. The autonomy and relatedness coding system. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Land D. Attachment in adolescence. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York, NY, USA: The Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 319–335. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, McElhaney KB, Land DJ, Kuperminc GP, Moore CM, O'Beirne-Kelley H, et al. A Secure Base in Adolescence: Markers of Attachment Security in the Mother-Adolescent Relationship. Child Development. 2003;74:292–307. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Moore C, Kuperminc G, Bell K. Attachment and adolescent psychosocial functioning. Child Development. 1998;69(5):1406–1419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammaniti M, Van IJzendoorn MH, Speranza AM, Tambelli R. Internal working models of attachment during late childhood and early adolescence: An exploration of stability and change. Attachment & Human Development. 2000;2(3):328–346. doi: 10.1080/14616730010001587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 1987;16(5):427–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02202939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. New York: The Psychological Corporation; 1987. Beck Depression Inventory Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit D, Parker KCH. Stability and transmission of attachment across three generations. Child Development. 1994;65:1444–1456. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. New York: Basic Books; 1973. Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. New York: Basic Books; 1980. Attachment and loss: Vol. 3: Loss, sadness and depression. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. New York: Basic Books; 1988. A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV, Sparrow SA. Developing criteria for establishing interrater reliability of specific items: Applications to assessment of adaptive behavior. American Journal of Mental Deficiency. 1981;86:127–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Cole-Detke H, Kobak R. Attachment processes in eating disorder and depression. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(2):282–290. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH. Family economic hardship and adolescent adjustment: Mediating and moderating processes. In: Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, editors. Consequences of growing up poor. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Ge X, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL. Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development. 1994;65 (2):541–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell JA, Treboux D, Waters E. Alternatives to the Adult Attachment Interview: Self-reports of attachment style and relationships with mothers and partners. Paper presented at the Biennial Meetings of the Society for Research in Child Development; New Orleans, Louisiana. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Crowell JA, Treboux D, Waters E. Stability of attachment representations: The transition to marriage. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(4):467–479. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.4.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies P. Emotional security as a regulatory process in normal development and the development of psychopathology. Development & Psychopathology. 1996;8(1):123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Daley SE, Hammen C. Depressive symptoms and close relationships during the transition to adulthood: Perspectives from dysphoric women, their best friends, and their romantic partners. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(1):129–141. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Kobak RR. Psychophysiology in attachment interviews: Converging evidence for deactivating strategies. Annual Progress in Child Psychiatry & Child Development. 1993:80–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrooks MA, Davidson CE, Chazan R. Psychosocial risk, attachment, and behavior problems among school-aged children. Development & Psychopathology. 1993;5(3):389–402. [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrooks MA, Graham CA. Security of attachment and parenting: Homeless and low-income housed mothers and infants. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1999;69 (3):337–346. doi: 10.1037/h0080408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein S. Amherst: Massachusetts; 1983. Scoring and Interpretation of the Mother-Father-Peer Scale. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Flanagan AS. The influence of earlier relationships on marriage: An attachment perspective. In: Halford WK, Markman HJ, editors. Clinical handbook of marriage and couples interventions. Chichester, England UK: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1997. pp. 179–202. [Google Scholar]

- George C, Kaplan N, Main M. third edition Department of Psychology, University of California; Berkeley: 1996. Adult Attachment Interview. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Interpersonal factors in an emerging developmental model of depression. In: Johnson SL, Hayes AM, Field TM, Schneiderman N, McCabe PM, editors. Stress, coping and depression. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. pp. 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Shih J, Altman T, Brennan PA. Interpersonal impairment and the prediction of depressive symptoms in adolescent children of depressed and nondepressed mothers. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(5):571–577. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046829.95464.E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Denver, Colorado: University of Denver; 1988. Manual for the self-perception profile for adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser RM, Sweeney MM. Does poverty in adolescence affect the life chances of high school graduates? In: Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, editors. Consequences of growing up poor. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Cole H. Attachment and meta-monitoring: Implications for adolescent autonomy and psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Disorders and dysfunctions of the self. Rochester Symposium on Developmental Psychopathology. Vol. 5. Rochester, NY, USA: University of Rochester Press; 1994. pp. 267–297. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Cole H, Ferenz-Gillies R, Fleming W, Gamble W. Attachment and emotion regulation during mother-teen problem-solving: A control theory analysis. Child Development. 1993;64:231–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Sceery A. Attachment in late adolescence: Working models, affect regulation and representations of self and others. Child Development. 1988;59:135–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Sudler N, Gamble W. Attachment and depressive symptoms during adolescence: A developmental pathways analysis. Development & Psychopathology. 1991;3 (4):461–474. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Goldwyn R. University of California; Berkeley: 1994. Adult attachment rating and classification system, Version 6.0. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Goldwyn R. University of California; Berkeley: 1998. Adult attachment scoring and classification system. Unpublished manuscript, Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J. Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. In: Bretherton I, Waters E, editors. Growing Points in Attachment Theory and Research, Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Vol. 50. 1985. pp. 66–104. Serial No. 209. [Google Scholar]

- McElhaney KB, Allen JP. Autonomy and Adolescent Social Functioning: The Moderating Effect of Risk. Child Development. 2001;72:220–231. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Jayaratne TE, Ceballo R, Borquez J. Unemployment and work interruption among African American single mothers: Effects on parenting and adolescent socioemotional functioning. Special Issue: Children and poverty. Child Development. 1994;65:562–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phares V. Where's Poppa? The relative lack of attention to the role of fathers in child and adolescent psychopathology. American Psychologist. 1992;47:656–664. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.5.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phares V, Compas BE. The role of fathers in child and adolescent psychopathology: Make room for daddy. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:387–412. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radke-Yarrow M, Cummings EM, Kuczynski L, Chapman M. Patterns of attachment in two- and three-year-olds in normal families and families with parental depression. Child Development. 1985;56(4):884–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist. 2000;55(1):68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Laub JH. Urban poverty and the family context of delinquency: A new look at structure and process in a classic study. Special Issue: Children and poverty. Child Development. 1994;65:523–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman ME, Abramson LY, Semmel A, von Baeyer C. Depressive attributional style. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1979;88(3):242–247. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.88.3.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Lorenz FO, Wu C-i, Conger RD. Social network and marital support as mediators and moderators of the impact of stress and depression on parental behavior. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29(2):368–381. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA. Psychopathology as an outcome of development. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:251–268. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497002046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teachman JD, Paasch KM, Day RD, Carver KP. Poverty during adolescence and subsequent educational attainment. In: Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, editors. Consequences of growing up poor. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. Attachment representations in mothers, fathers, adolescents, and clinical groups: A meta-analytic search for normative data. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(1):8–21. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn BE, Egeland BR, Sroufe LA, Waters E. Individual differences in infant-mother attachment at twelve and eighteen months: Stability and change in families under stress. Child Development. 1979;50(4):971–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinfield NS, Sroufe LA, Egeland B. Attachment from infancy to early adulthood in a high-risk sample: Continuity, discontinuity, and their correlates. Child Development. 2000;71:695–702. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P, Becker-Stoll F. Stability of attachment representations during adolescence: The influence of ego-identity status. Journal of Adolescence. 2002;25(1):107–124. doi: 10.1006/jado.2001.0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]