Abstract

The evidence for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) playing a role in prostate carcinogenesis comes mainly from associations between reported PAH exposures and prostate cancer in epidemiologic studies. Associations between prostate cancer and DNA repair genotypes and phenotypes have also been reported, lending further credence to a PAH-induced carcinogenesis pathway in prostate cancer. Recent work that demonstrates the human prostate has metabolic enzyme activity necessary for PAH activation and will form DNA adducts upon exposure to PAH further supports PAH carcinogenesis. We have demonstrated the presence of PAH-DNA adducts in prostate cancer cases, but further validation of this biomarker as a carcinogenic agent in human prostate is needed.

Keywords: DNA damage, Benzo(a)pyrene, Immunohistochemistry, DNA repair

1. Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) are large aromatic planar compounds that comprise a class of over 200 chemicals with three or more benzene rings and are ubiquitous in the environment. PAH result from incomplete combustion processes [1] and occur naturally as a result of forest fires and in coal, peat, crude oil, and shale oils [2]. Human exposure to carcinogenic PAH can come from our diet by consumption of foods such as grilled meats, leafy vegetables and grains [3,4], tobacco smoke [5], and in various occupational settings [6].

Scientific evidence supportive of the carcinogenic potential of PAH goes back as early as 1775, when the British surgeon Sir Percival Pott demonstrated a correlation between the exposure of chimney sweeps to soot and the incidence of scrotal cancer [7]. In the prostate, the carcinogenic potential of PAH has long been known through in vitro studies of mouse prostate cells [8]. Likewise, the importance of metabolic activation of PAH to induce transformation in prostate cells was also demonstrated some time ago [9]. Interestingly, in vivo induction of prostate cancer from PAH exposure has only recently been demonstrated, albeit in an indirect fashion. Guttenplan et al. [10] administered benzo[a]pyrene to mice through gavage for 9 months and found induction of prostate mutagenesis.

2. Epidemiologic studies of PAH exposures and prostate cancer

Occupational PAH exposure is associated with PAH-DNA adduct formation in lymphocytes [11, 12], and notably the epidemiologic evidence for a link between PAH and prostate carcinogenesis comes mainly through occupational studies [13]. An occupational study of fatal prostate in the motor vehicle industry cancer found an association with work in core and mold making jobs and metal melting and pouring jobs [14]. The high temperature associated with mold and core making and casting processes often results in the emission of several pyrolysis-induced PAH, including benzo[a]-pyrene. In three separate studies that examined specific occupational exposures, two found modest associations with selected PAH sources [15,16], while the third found no association with PAH-related exposures [17]. Three case-control studies have found an elevated prostate cancer risk for exposure to diesel fumes [16,18,19]. However, other studies have failed to find a prostate cancer association between jobs with potential exposures to diesel or engine exhaust [20–22]. Timing of exposure may be important; with PAH exposures that occur years before disease onset potentially having a greater impact upon prostate carcinogenesis. The highest elevated standard mortality ratio (SMR) for prostate cancer in Swedish chimney sweeps, who are occupationally exposed to high levels of PAH, was with at least 10 years of occupational exposure (the SMR remained elevated for 20–29 and 30+ years of exposure) and at least 20 years since the first exposure [23].

In terms of the relationship between the two other main sources of PAH, diet and smoking, and prostate cancer, the epidemiologic evidence is modest at best. While there appears to be an association between meat consumption and prostate cancer [24], no studies have attempted to measure PAH content through diet (either as result of meat preparation or as constituents of other food stuffs) in relation to prostate cancer risk. The relationship between smoking and prostate cancer has been extensively studied, but no clear association between the two is apparent [25]. Whatever risk smoking may confer towards prostate cancer, it is modest and likely restricted to individuals with other prostate cancer risk factors that can potentially interact with tobacco to produce a carcinogenic effect in the prostate. For instance, several studies have found that smokers with genotypes for the detoxifying enzymes of glutathione-S-transferases that confer lower enzyme activity may be at increased risk for prostate cancer [26,27].

3. PAH metabolism

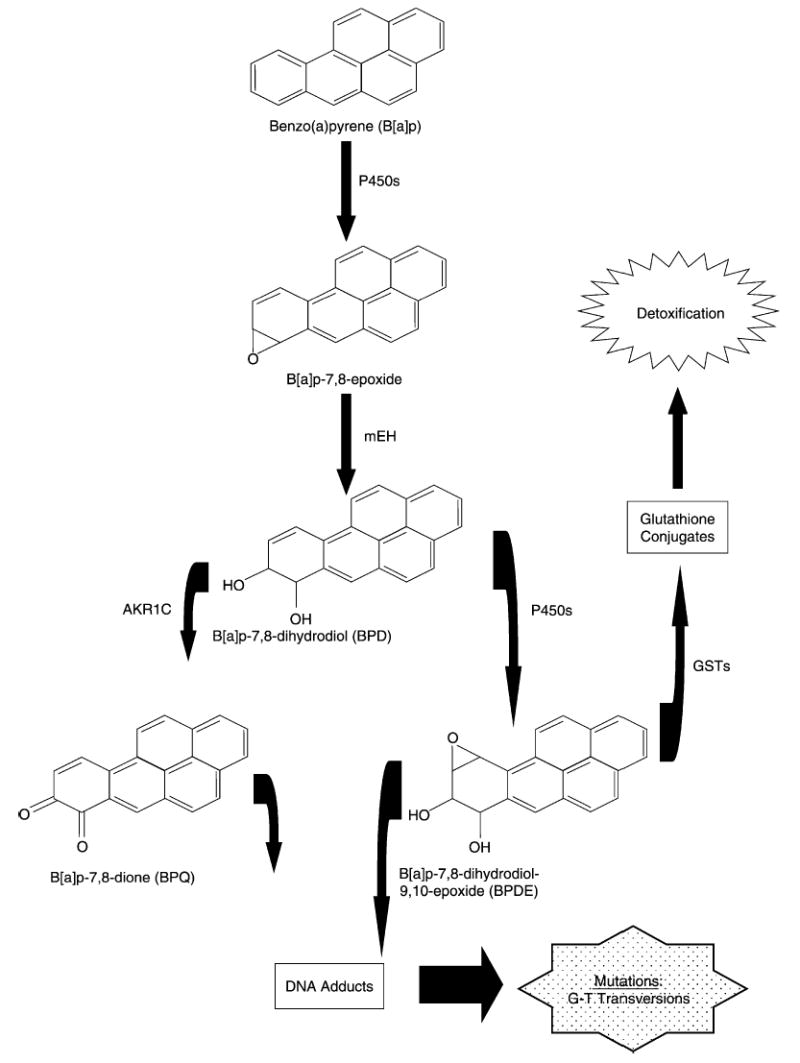

PAH are metabolized in the liver and other tissues by the cytochrome P450 enzyme system into reactive electrophiles [28]. These reactive species are then detoxified and made water soluble through phase II conjugation with glutathione or glucuronic acid [29]. However, the reactive electrophilic PAH species can also bind to cellular macromolecules such as DNA, forming what are known as PAH-DNA adducts. We shall use the common prototype PAH, the five-benzene-ring compound, benzo(a)pyrene, B[a]p, to illustrate the general mechanisms involved in PAH-DNA adduct formation. B[a]p is initially oxidized to an epoxide (e.g. b(a)p-7,8-epoxide) by cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP1A1 or CYP1B1 [4] (Fig. 1). Although both of these enzymes are expressed in the prostate (Table 1), hormonal factors such as androgen dependency may affect which isozyme is actually invoked [30]. Other factors that may contribute to enzyme selectivity include genetic polymorphisms in enzymes and their inducers (e.g. aryl hydrocarbon receptor, AhR), promoter methylation [31], competition and the presence of inhibitors [32]. Interestingly, CYP1B1, which also catalyzes the hydroxylation of estrogens, has a higher expression in the prostate peripheral zone (where most cancers arise, compared with the transition zone [33]; and, is overexpressed in prostate carcinoma and prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia [34]. After the epoxide (b(a)p-7,8-epoxide) is formed, it may be further metabolized by microsomal epoxide hydrolase (mEH), which is also expressed in the prostate (Table 1), to form a dihydrodiol (b(a)p-7,8-dihydrodiol, BPD) (Fig. 1). This dihydrodiol sits at the fulcrum between two critical subpathways, both of which may create metabolites that can damage DNA. The most common route involves metabolism of the dihydrodiol (BPD) by CYP1A1, CYP1A2 or CYP1B1 [35] to form a diol-epoxide (b(a)p-7,8-dihydrodiol-9,10-epoxide, BPDE), which may covalently bind to DNA forming a BPDE-DNA adduct [36]. Of the four possible diastereomers of BPDE, the (+)-anti-BPDE is the most abundant [37], mutagenic [38], and tumorogenic [39]. Alternatively, the dihydrodiol (BPD) may be metabolized by enzymes in the aldo-keto reductase 1C (AKR1C) family to form a catechol intermediate, which may be subsequently autooxidized to an ortho-quinone (b(a)p-7,8-dione, BPQ) [40]. Expression of AKR1C family isozymes has been observed in prostate cells [41]; however, these enzymes are also charged with metabolizing steroid hormones such as progesterone and dihydrotestoster-one (DHT). BPQ may exert its action directly by binding to DNA or indirectly through formation of reactive oxygen species [42]. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the potentially damaging diol-epoxide intermediates can be ‘detoxified’ and made more water soluble for subsequent excretion via renal/hepatic routes through conjugation by enzymes in the glutathione-S-transferase (GST) superfamily. There are four main classes of GSTs: (1) α (GSTA); (2) μ (GSTM); (3) π (GSTP); and (4) θ (GSTT) [43]. All of these are expressed in the prostate (Table 1); however, since conjugation requires both the binding of glutathione and the GST enzyme [44], the stereochemistry may affect which isozyme more efficiently conjugates each PAH diol-epoxide. For example, the catalytic efficiency of GSTM1 is substantially greater than that of GSTP1 for the (+)-anti-BPDE enantiomer [45]. Other factors including genetic polymorphisms and promotor methylation may also affect enzyme activity. In particular, promoter methylation of GSTP1 [46] and GSTM1 [47] has been shown to silence or diminish, respectively, enzyme activity in prostate cancer cells.

Fig. 1.

Enzymatic conversion pathways of benzo[a]pyrene catalyzed by cytochrome P450s (P450s) and the aldo-keto reductase 1C (AKR1C) into activated compounds BPQ and BPDE that can bind with the 2-amino group of deoxyguanosine to form DNA adducts. Also depicted is the detoxification pathway catalyzed by glutathione-S-transferases (GSTs).

Table 1.

Selected metabolic enzymes that act on PAH substrates and show activity in the prostate

| Enzyme | Activity level toward PAH substrates | Activity level in prostate | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP1A1 | +++ | ++ | Associations between exon 7 polymorphisms and PAH-DNA adduct levels in white blood cells |

| CYP1A2 | ++ | ++ | Induced in prostate tumor cells by B[a]p |

| CYP1B1 | +++ | +++ | Coding polymorphisms associated with prostate cancer risk |

| CYP2C9 | + | ++ | Active in both normal and neoplastic prostate |

| CYP3A4 | + | + | Highly variable expression in humans |

| meH | +++ | ++ | Highly expressed in prostate cancer; key enzyme in activation of B[a]p |

| GSTT1 | + | ++ | Not expressed in prostate cancer; null genotype does not appear to influence PAH metabolites |

| GSTM1 | +++ | ++ | Null genotype may influence PAH-DNA adduct levels; evidence for promoter methylation in prostate cancer |

| GSTP1 | ++ | +++ | Stereo-specific activities toward B[a]p; methylation of promoter region inactivates gene in prostate cancer |

| GSTA1 | ++ | + | Increased activity associated with inflammation |

+low; ++, moderate; +++, high.

Classically for the highly reactive (+)-anti-benzopyrenediol-epoxide, stable adduct formation occurs at the 2-amino group of deoxyguanosine [48]. Alternately, unstable PAH-DNA adducts can be formed via p450 mediated one-electron oxidation, but these adducts quickly depurinate leading to apurinic sites in DNA [49]. While it is not clear which type of adducts, stable or unstable, have a greater role in carcinogenesis, both kinds likely have some carcinogenic potential [50,51]. Adduct formation is thought to be a necessary but not sufficient step in PAH-induced carcinogenesis, but it is likely to be directly relevant to the ability of PAH to cause mutations and cancer [52]. If an adduct forms and is not repaired, a mutation in the DNA code can occur during cell division, propagating the damage in successive generations of the cell [53]. If a mutation occurs in a critical gene, such as a proto-oncogene, tumor suppresser gene or DNA caretaker gene, this damage can represent one of the hits in the multi-hit model of carcinogenesis. For example, if the BPDE-and BPQ-DNA adducts are not repaired they may cause irreversible G to T transversions [54] and B[a]p has been shown to preferentially form adducts with DNA bases in the p53 tumor suppresser gene that are the ‘hot spots’ for mutations in lung cancer [55]. Furthermore, levels of G to T transversions in p53 in breast [56] and lung tumors [57] are higher than in non-tumor tissue and among smokers compared to non-smokers [58]. However, studies evaluating the potential role of PAH-induced G to T transversions in tumor suppressors or proto-oncogenes in prostate cancer are lacking.

4. DNA damage and repair in prostate carcinogenesis

If the carcinogenic potential of PAH comes mainly from its ability to form DNA adducts, then DNA repair capacity should influence prostate cancer risk. Several recent studies have found that germ line mutations and polymorphisms in DNA-damage response genes, including OGG1, XRCC1, and CHEK2, have been associated with prostate cancer risk [59–61]. We examined the XRCC1 codon 399 and XPD codons 312 and 751 polymorphisms in relation to prostate cancer risk and found that only the XPD codon 312 Asn allele showed a modest association with increased prostate cancer risk [60]. However, when both the XPD codon 312 Asn and XRCC1 codon 399 Gln alleles were present in their homozygous states, the risk for prostate cancer increased 4.8-fold. While mechanistically genetic interactions are thought to be more likely between genes involved in the same biologic pathways, it is not unprecedented to find an increased joint effect between genes acting in different pathways. In the case of XRCC1 (involved in the base excision repair (BER) pathway) and XPD (involved in the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway), because DNA damage caused by a mixture of environmental exposures may require both the BER or NER pathways, our results suggested that a reduction in the efficiencies of only one of these pathways may not increase disease risk to the same extent as when both pathways are compromised. Genetic variation in both XRCC1 [62] and XPD [63] has been linked to DNA adduct levels in blood.

Other evidence that the NER pathway is important in prostate cancer comes from a study that directly measured NER capacity using a plasmid-based host reactivation assay. Hu et al. [64] showed that reduced NER capacity was associated with prostate cancer risk in a dose response fashion. Prostate tumor progression may also be influenced by aberrant DNA repair as there is discordance between expression and function of DNA repair genes in malignant prostate cancer cells [65]. Human prostate epithelial cells can activate B[a]p and increasing concentrations of B[a]p result in increasing DNA damage [66]. Overall, it appears that PAH can induce DNA damage in prostate cells and DNA repair capacity is related to prostate cancer susceptibility, but what is lacking is an intermediate biomarker in the PAH-prostate carcinogenesis pathway indicative of a biologically effective dose of PAH exposure that will initiate the carcinogenesis process.

5. Measuring DNA adducts and DNA adduct formation in prostate cancer

The methodology to measure DNA adducts in humans has become more reliable in recent years, with a level of sensitivity that allows detection of background carcinogenic adduct levels in environmentally exposed persons. Typically, PAH-DNA adducts in human tissues and cells can be detected with as little as one DNA adduct per 109 nucleotides in 5–100 μg of DNA [67]. A number of methods exist to measure PAH-DNA adducts, each with its own performance characteristics and intended target compound(s). These methods include, but are not limited to, a high performance liquid chromatography technique that specifically measures the B[a]p tetrol [68], the 32P-postlabeling method that measures aromatic DNA adducts including PAH [69], and immuno methods (ELISA and immunohistochemistry) that measure PAH-DNA adducts as a class of chemicals [70].

Of available techniques, only the immunohistochemical approach is suitable for the measurement of PAH-DNA adducts in formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissue. The assay uses standard immuno-peroxidase techniques and a monoclonal antibody (5D11) that detects PAH-DNA adducts [71]. The advantages of this assay are that it can be used on very small tissue samples, can evaluate adduct levels in adjacent morphologic structures in the same tissue, and has good sensitivity and specificity for measuring DNA adducts [72]. The disadvantage of this assay is that procedures to convert staining intensity scores to quantified adduct levels (e.g. adducts per 108 nucleotides) have not been established [70], but in terms of quantifying DNA adduct burden there is little difference in the variability of the immunohistochemical approach compared with assays that measure adducts per nucleotide [73]. Although the 5D11 antibody was raised against B[a]p-diol-epoxide (BPDE)-DNA adducts, it cross-reacts with other PAH that form diol-epoxide adducts [70]. Humans are exposed to complex mixtures of PAH and multiple adduct species are likely to be present in human tissues. Immunohistochemical assays for PAH-DNA adducts, including several that have used the 5D11 antibody, have previously demonstrated the ability to reflect differences in environmental exposures to PAH [74,75]. Studies using immunohistochemistry with the 5D11 antibody and cells treated with BPDE have also shown an excellent correlation between treatment dose and staining intensity [75].

An important methodologic issue in measuring PAH-DNA adducts in tissue samples concerns the histologic variability across a sample and the concomitant measurement variation. To arrive at a single PAH-DNA adduct measurement, typically a technician has to sample and score 50–100 individual cells in several high power fields. In breast tissue, intraclass correlation analyses have shown that scoring procedures for PAH-DNA adduct levels are reliable [76] with intraclass correlation coefficients of 0.82 in tumor tissue, 0.93 in non-tumor tissue, and 0.74 in benign tissue. Despite this high reliability, the technician can have a significant effect on scoring [76].

The averaging of two independent measurements produces higher test–retest reliability than a lone measurement. In our study of PAH-DNA adducts in prostate [77], single reviewers had correlations of 53–58% for tumor cells and 73–74% for non-tumor cells, but a reliability study of 59 samples that both technicians scored twice resulted in reliability estimates of 83% for both tumor and non-tumor cells. The reliability of a lone scorer in the analyses of breast cells was as high or higher (82% for tumor, 93% for non-tumor) than a reliability estimate that used the average of two independent scores in prostate cells. This suggests that immunohistochemical staining intensity is more difficult to consistently score in prostate than in breast, which probably reflects the more complex histology of prostate in comparison with breast, and would suggest that a scoring protocol using an immunohistochemical technique in prostate cells should involve at least two technicians.

These reliability findings are important in light of the nascence of PAH-DNA adduct studies in prostate compared with similar research in lymphocytes, lung and breast tissue. The few studies that have quantified PAH-DNA adducts in prostate are summarized in Table 2. Two separate in vitro studies of human prostate cells from the same group demonstrated the induction of B[a]p-DNA adduct formation in prostate cells [32,78]. Interestingly, B[a]p-DNA adducts were still measurable by 32P-postlabeling for up to 14 days following a 24-h exposure to 50 mM B[a]p [78]. Only two other studies have demonstrated the formation of PAH-DNA adducts in prostate cells, and both of these were done in animal models [79,80]. Our recent report of the distribution of PAH-DNA adducts in prostates of prostate cancer cases was the first to show variation of PAH-DNA adducts in a human study population [77].

Table 2.

Studies that have detected PAH-DNA adducts in prostate cells

| Study | Adduct type | Method | Cell type | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rybicki et al. [60,77] | B[a]p | IH | Human paraffin embedded malignant tissue | Adduct levels lower in tumor compared with adjacent normal cells |

| Martin et al. [78] | B[a]p | 32P | Human fresh benign tissue after surgery | Correlation between amount of B[a]p administered and single strand DNA breakage |

| Williams et al. [31] | B[a]p | 32P | Human fresh benign tissue after surgery | Cells seeded in culture with B[a]p and PhIP, higher levels of PhIP adducts observed |

| Ramesh et al. [79] | B[a]p | 32P | Rat | Of lung, prostate, testis and liver, only lung had higher adduct levels than prostate |

| Feng et al. [80] | C8-2-aminoflourene | 32P | Hamster | Adduct levels not dependent on slow/fast acetylator status |

IH, immunohistochemistry; 32P, 32P postlabeling.

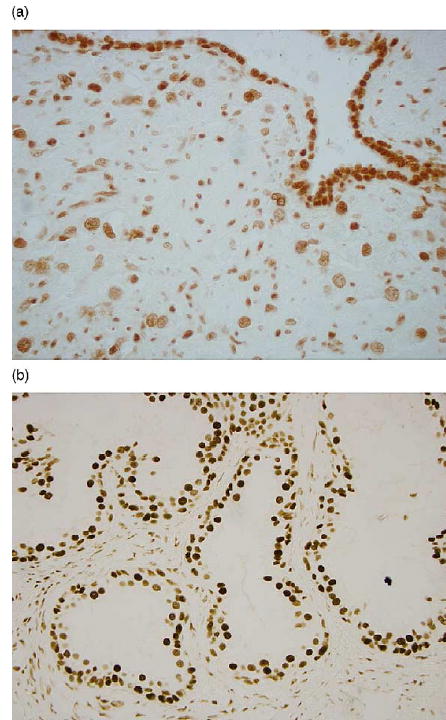

In 130 paired samples of non-tumor and tumor prostate cells from recently diagnosed prostate cancer cases, we found two separate normal distributions of PAH-DNA adducts where the mean level of adducts in non-tumor cells was 0.126 optical density (OD) units higher than that in tumor cells (O.299 vs. 0.173). The study sample variance for PAH-DNA adduct levels in non-tumor cells was also greater than that of adduct levels in tumor cells (0.0030 OD vs. 0.0014 OD). Despite these differences, a strong correlation between paired adduct levels in the two cell types was found (r = 0.56; P < 0.0001). The clinical variables we found significantly associated with PAH-DNA adduct levels in tumor cells included primary Gleason grade, tumor volume and log-transformed prostate-specific antigen (PSA) at time of diagnosis. Tumors with a primary Gleason grade of 5 had significantly lower PAH-DNA adduct levels than tumor cells with a primary Gleason grade of 3 or 4 (P < 0.0001 for both). Tumors that involved 10% or less of the prostate gland had significantly higher PAH-DNA adduct levels than tumors that involved 15–20% of the prostate gland (P = 0.004). PSA levels were inversely associated with PAH-DNA adduct levels in tumor cells (P = 0.009). Interestingly, increasing primary Gleason grade was associated with increasing PAH-DNA adduct levels in adjacent non-tumor cells (P = 0.008). Fig. 2(a) depicts the contrast in staining intensity for PAH-DNA adducts in prostate epithelial cells with respect cell histology. In general, non-tumor cells stain with greater intensity than tumor cells. Overall, our findings suggest that PAH-DNA adduct levels in the prostate are in flux during prostate carcinogenesis, but our cross-sectional study is limited and cannot directly address whether DNA adduct formation in benign prostate predisposes to a later increased risk for prostate cancer. We have conducted pilot studies demonstrating that PAH-DNA adducts can be detected in normal prostate cells of specimens retrieved from men without a prostate cancer diagnosis (Fig. 2(b)). Whether pre-cancer PAH-DNA adducts predispose to prostate cancer will require a large prospective study; ideally in a cohort of men with archived benign prostate tissue who can be followed for development of prostate cancer. Only one biomarker study of PAH-DNA adduct formation prior to cancer onset has been conducted, but that study examined lung cancer and was limited to relating cancer risk to PAH-DNA adduct formation in lymphocytes [81].

Fig. 2.

(a) 5D11 monoclonal antibody staining of epithelial prostate normal and tumor cells in a tissue section removed from a prostatectomy sample. (b) 5D11 monoclonal antibody staining of epithelial prostate normal cells in a tissue section removed from a needle prostate biopsy of a patient without prostate cancer.

6. PAH-DNA adduct distribution throughout the prostate

Since most prostate adenocarcinoma arises from the peripheral zone of the prostate, it would be of interest to know the distribution of PAH-DNA adduct levels throughout the prostate gland. Therefore, we conducted a pilot study in 54 prostatectomy specimens to determine if PAH-DNA adduct concentrations in normal cells differed significantly among the three zonal regions in the prostate. In each subject’s prostatectomy specimen, slides from multiple blocks were examined so that three zones of the prostate, peripheral, transitional and central, could be studied. Mean adduct levels in the three different regions were very similar: central = 0.20 ± 0.05 OD; transition = 0.21 ± 0.05 OD; peripheral = 0.21 ± 0.05 OD. To determine whether these means were significantly different from each other, three separate paired t-tests were performed. The mean difference between the different zonal regions were as follows: central vs. transition: 0.012 ± 0.046 OD (P = 0.06); central vs. peripheral: 0.012 ± 0.049 OD (P = 0.08); transition vs. peripheral: 3.7 × 10−6 ± 0.055 OD (P = 0.99). Our results demonstrated that PAH-DNA adducts are homogeneous throughout the normal cells of the prostate.

7. Conclusions

While the carcinogenic potential of PAH in the human prostate has long been suspected based on animal studies and epidemiologic associations between prostate cancer risk and occupations with PAH exposures, biomarker studies confirming this etiologic pathway have been lacking. Recent work with prostate tissue that has shown the presence of the metabolic enzyme activity necessary for PAH activation and the formation of DNA adducts upon exposure to PAH supports the biologic feasibility of PAH carcinogenesis. The detection and quantification of PAH-DNA adduct formation in the PAH prostate carcinogenesis pathway is key, since it substantiates a well-established mechanism of environmental genotoxicity through DNA damage that can lead to carcinogenic mutations [55]. Our demonstration of PAH-DNA adducts in prostate cancer cases [77] supports the notion that PAH carcinogenesis in the prostate is initiated through DNA adduct formation, but it fails to establish a temporal relationship between adduct formation and cancer onset. The ultimate importance of PAH-DNA adduct formation in prostate carcinogenesis will require validation of this biomarker as a true agent of effect through human follow-up studies that can establish a temporal relationship between the two.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Christine Neslund-Dudas for contributing to the literature review for this manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 ES011126 and RO1 ES011126-S1.

References

- 1.Yang SK, Silverman BD, editors. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Carcinogenesis: Structure-activity Relationships. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tolbert PE. Oils and cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:386–405. doi: 10.1023/a:1018409422050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips DH. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the diet. Mutat Res. 1999;443:139–147. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(99)00016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimada T, Yamazaki H, Foroozesh M, Hopkins NE, Alworth WL, Guengerich FP. Selectivity of polycyclic inhibitors for human cytochrome P450s 1A1, 1A2, and 1B1. Chem Res Toxicol. 1998;11:1048–1056. doi: 10.1021/tx980090+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scherer G, Frank S, Riedel K, Meger-Kossien I, Renner T. Biomonitoring of exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons of nonoccupationally exposed persons. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:373–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schoket B. Monitoring occupational exposure to carcinogens. IARC Sci Publ. 1993:341–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potter M. Percivall Pott’s contribution to cancer research. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1963;10:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen TT, Heidelberger C. Quantitative studies on the malignant transformation of mouse prostate cells by carcinogenic hydrocarbons in vitro. Int J Cancer. 1969;4:166–178. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910040207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grover PL, Sims P, Huberman E, Marquardt H, Kuroki T, Heidelberger C. In vitro transformation of rodent cells by K-region derivatives of polycyclic hydrocarbons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:1098–1101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.6.1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guttenplan JB, Chen M, Kosinska W, Thompson S, Zhao Z, Cohen LA. Effects of a lycopene-rich diet on spontaneous and benzo[a]pyrene-induced mutagenesis in prostate, colon and lungs of the lacZ mouse. Cancer Lett. 2001;164:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00705-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ovrebo S, Haugen A, Hemminki K, Szyfter K, Drablos PA, Skogland M. Studies of biomarkers in aluminum workers occupationally exposed to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Cancer Detect Prev. 1995;19:258–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pavanello S, Siwinska E, Mielzynska D, Clonfero E. GSTM1 null genotype as a risk factor for anti-BPDE-DNA adduct formation in mononuclear white blood cells of coke-oven workers. Mutat Res. 2004;558:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2003.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parent ME, Siemiatycki J. Occupation and prostate cancer. Epidemiol Rev. 2001;23:138–143. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a000779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown DA, Delzell E. Motor vehicle manufacturing and prostate cancer. Am J Ind Med. 2000;38:59–70. doi: 10.1002/1097-0274(200007)38:1<59::aid-ajim7>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nadon L, Siemiatycki J, Dewar R, Krewski D, Gerin M. Cancer risk due to occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Am J Ind Med. 1995;28:303–324. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aronson KJ, Siemiatycki J, Dewar R, Gerin M. Occupational risk factors for prostate cancer: results from a case-control study in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:363–373. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Gulden JW, Kolk JJ, Verbeek AL. Work environment and prostate cancer risk. Prostate. 1995;27:250–257. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990270504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seidler A, Heiskel H, Bickeboller R, Elsner G. Association between diesel exposure at work and prostate cancer. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1998;24:486–494. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siemiatycki J, Wacholder S, Richardson L, Dewar R, Gerin M. Discovering carcinogens in the occupational environment. Methods of data collection and analysis of a large case-referent monitoring system. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1987;13:486–492. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elghany NA, Schumacher MC, Slattery ML, West DW, Lee JS. Occupation, cadmium exposure, and prostate cancer. Epidemiology. 1990;1:107–115. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199003000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen ES. A follow-up study on the mortality of truck drivers. Am J Ind Med. 1993;23:811–821. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700230514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boffetta P, Stellman SD, Garfinkel L. Diesel exhaust exposure and mortality among males in the American Cancer Society prospective study. Am J Ind Med. 1988;14:403–415. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700140405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evanoff BA, Gustavsson P, Hogstedt C. Mortality and incidence of cancer in a cohort of Swedish chimney sweeps: an extended follow up study. Br J Ind Med. 1993;50:450–459. doi: 10.1136/oem.50.5.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolonel LN. Fat, meat, and prostate cancer. Epidemiol Rev. 2001;23:72–81. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a000798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hickey K, Do KA, Green A. Smoking and prostate cancer. Epidemiol Rev. 2001;23:115–125. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a000776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Autrup JL, Thomassen LH, Olsen JH, Wolf H, Autrup H. Glutathione S-transferases as risk factors in prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1999;8:525–532. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199912000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mao GE, Morris G, Lu QY, Cao W, Reuter VE, Cordon-Cardo C, et al. Glutathione S-transferase P1 Ile105Val polymorphism, cigarette smoking and prostate cancer. Cancer Detect Prev. 2004;28:368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller EC, Miller JA. Mechanisms of chemical carcinogenesis. Cancer. 1981;47:1055–1064. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810301)47:5+<1055::aid-cncr2820471302>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sipes IG, Gandolfi AJ. Biotransformation of toxicants. In: Amdur M, Doull J, Klaassen C, editors. Casarett and Doull’s Toxicology: The Basic Science of Poisons. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1991. pp. 88–126. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sterling KM, Jr, Cutroneo KR. Constitutive and inducible expression of cytochromes P4501A (CYP1A1 and CYP1A2) in normal prostate and prostate cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2004;91:423–429. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Widschwendter M, Siegmund KD, Muller HM, Fiegl H, Marth C, Muller-Holzner E, et al. Association of breast cancer DNA methylation profiles with hormone receptor status and response to tamoxifen. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3807–3813. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams JA, Martin FL, Muir GH, Hewer A, Grover PL, Phillips DH. Metabolic activation of carcinogens and expression of various cytochromes P450 in human prostate tissue. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1683–1689. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.9.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ragavan N, Hewitt R, Cooper LJ, Ashton KM, Hindley AC, Nicholson CM, et al. CYP1B1 expression in prostate is higher in the peripheral than in the transition zone. Cancer Lett. 2004;215:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carnell DM, Smith RE, Daley FM, Barber PR, Hoskin PJ, Wilson GD, et al. Target validation of cytochrome P450 CYP1B1 in prostate carcinoma with protein expression in associated hyperplastic and premalignant tissue. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:500–509. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimada T, Hayes CL, Yamazaki H, Amin S, Hecht SS, Guengerich FP, Sutter TR. Activation of chemically diverse procarcinogens by human cytochrome P-450 1B1. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2979–2984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sims P, Grover PL, Swaisland A, Pal K, Hewer A. Metabolic activation of benzo(a)pyrene proceeds by a diol-epoxide. Nature. 1974;252:326–328. doi: 10.1038/252326a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang SK, McCourt DW, Roller PP, Gelboin HV. Enzymatic conversion of benzo(a)pyrene leading predominantly to the diol-epoxide r-7,t-8-dihydroxy-t-9,10-oxy-7,8,9, 10-tetrahydrobenzo(a)pyrene through a single enantiomer of r-7, t-8-dihydroxy-7,8-dihydrobenzo(a)pyrene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:2594–2598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.8.2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wood AW, Chang RL, Levin W, Thakker DR, Yagi H, Sayer JM, et al. Mutagenicity of the enantiomers of the diastereomeric bay-region benzo(c)phenanthrene 3,4-diol-1,2-epoxides in bacterial and mammalian cells. Cancer Res. 1984;44:2320–2324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levin W, Chang RL, Wood AW, Thakker DR, Yagi H, Jerina DM, Conney AH. Tumorigenicity of optical isomers of the diastereomeric bay-region 3,4-diol-1,2-epoxides of benzo(c)phenanthrene in murine tumor models. Cancer Res. 1986;46:2257–2261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burczynski ME, Penning TM. Genotoxic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon ortho-quinones generated by aldo-keto reductases induce CYP1A1 via nuclear translocation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Cancer Res. 2000;60:908–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Penning TM, Burczynski ME, Jez JM, Hung CF, Lin HK, Ma H, et al. Human 3alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase isoforms (AKR1C1-AKR1C4) of the aldo-keto reductase superfamily: functional plasticity and tissue distribution reveals roles in the inactivation and formation of male and female sex hormones. Biochem J. 2000;351:67–77. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flowers L, Bleczinski WF, Burczynski ME, Harvey RG, Penning TM. Disposition and biological activity of benzo[a] pyrene-7,8-dione. A genotoxic metabolite generated by dihydrodiol dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13664–13672. doi: 10.1021/bi961077w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayes JD, Pulford DJ. The glutathione S-transferase supergene family: regulation of GST and the contribution of the isoenzymes to cancer chemoprotection and drug resistance. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;30:445–600. doi: 10.3109/10409239509083491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mannervik B, Widersten M. Human glutathione transferases: classification tissue distribution, structure and functional properties. In: Pacifici GM, Fracchia GN, editors. Advances in Drug Metabolism in Man. European Commission; Brussels/Luxembourg: 1995. pp. 408–459. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sundberg K, Widersten M, Seidel A, Mannervik B, Jernstrom B. Glutathione conjugation of bay- and fjord-region diol epoxides of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by glutathione transferases M1-1 and P1-1. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:1221–1227. doi: 10.1021/tx970099w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jeronimo C, Usadel H, Henrique R, Oliveira J, Lopes C, Nelson WG, Sidransky D. Quantitation of GSTP1 methylation in non-neoplastic prostatic tissue and organ-confined prostate adenocarcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1747–1752. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.22.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lodygin D, Epanchintsev A, Menssen A, Diebold J, Hermeking H. Functional epigenomics identifies genes frequently silenced in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4218–4227. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weinstein IB, Jeffrey AM, Jennette KW, Blobstein SH, Harvey RG, Harris C, et al. Benzo(a)pyrene diol epoxides as intermediates in nucleic acid binding in vitro and in vivo. Science. 1976;193:592–595. doi: 10.1126/science.959820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cavalieri EL, Rogan EG, Devanesan PD, Cremonesi P, Cerny RL, Gross ML, Bodell WJ. Binding of benzo[a] pyrene to DNA by cytochrome P-450 catalyzed one-electron oxidation in rat liver microsomes and nuclei. Biochemistry. 1990;29:4820–4827. doi: 10.1021/bi00472a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Melendez-Colon VJ, Luch A, Seidel A, Baird WM. Cancer initiation by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons results from formation of stable DNA adducts rather than apurinic sites. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:1885–1891. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.10.1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cavalieri EL, Rogan EG, Chakravarti D. Initiation of cancer and other diseases by catechol ortho-quinones: a unifying mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:665–681. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8456-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Poirier MC, Weston A. Human DNA adduct measurements: state of the art. Environ Health Perspect. 1996;104:883–893. doi: 10.1289/ehp.96104s5883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gupta RC, Reddy MV, Randerath K. 32P-postlabeling analysis of non-radioactive aromatic carcinogen-DNA adducts. Carcinogenesis. 1982;3:1081–1092. doi: 10.1093/carcin/3.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bolton JL, Trush MA, Penning TM, Dryhurst G, Monks TJ. Role of quinones in toxicology. Chem Res Toxicol. 2000;13:135–160. doi: 10.1021/tx9902082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Denissenko M, Pao A, Tang M, Pfiefer G. Preferential formation of benzo[a]pyrene adducts at lung cancer mutational hotspots in p53. Science. 1996;274:430–432. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5286.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gunther T, Schneider-Stock R, Rys J, Niezabitowski A, Roessner A. p53 gene mutations and expression of p53 and mdm2 proteins in invasive breast carcinoma. A comparative analysis with clinico-pathological factors. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1997;123:388–394. doi: 10.1007/BF01240122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hollstein M, Shomer B, Greenblatt M, Soussi T, Hovig E, Montesano R, Harris CC. Somatic point mutations in the p53 gene of human tumors and cell lines: updated compilation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:141–146. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hainaut P, Pfeifer GP. Patterns of p53 G→T transversions in lung cancers reflect the primary mutagenic signature of DNA-damage by tobacco smoke. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:367–374. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu J, Zheng SL, Turner A, Isaacs SD, Wiley KE, Hawkins GA, et al. Associations between hOGG1 sequence variants and prostate cancer susceptibility. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2253–2257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rybicki BA, Conti DV, Moreira A, Cicek M, Casey G, Witte JS. DNA repair gene XRCC1 and XPD polymorphisms and risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:23–29. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-03-0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Gils CH, Bostick RM, Stern MC, Taylor JA. Differences in base excision repair capacity may modulate the effect of dietary antioxidant intake on prostate cancer risk: an example of polymorphisms in the XRCC1 gene. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:1279–1284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lunn RM, Langlois RG, Hsieh LL, Thompson CL, Bell DA. XRCC1 polymorphisms: effects on aflatoxin B1-DNA adducts and glycophorin a variant frequency. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2557–2561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tang D, Cho S, Rundle A, Chen S, Phillips D, Zhou J, et al. Polymorphisms in the DNA repair enzyme XPD are associated with increased levels of PAH-DNA adducts in a case-control study of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;75:159–166. doi: 10.1023/a:1019693504183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hu JJ, Hall MC, Grossman L, Hedayati M, McCullough DL, Lohman K, Case LD. Deficient nucleotide excision repair capacity enhances human prostate cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1197–1201. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fan R, Kumaravel TS, Jalali F, Marrano P, Squire JA, Bristow RG. Defective DNA strand break repair after DNA damage in prostate cancer cells: implications for genetic instability and prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8526–8533. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kooiman GG, Martin FL, Williams JA, Grover PL, Phillips DH, Muir GH. The influence of dietary and environmental factors on prostate cancer risk. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2000;3:256–258. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Poirier MC. Chemical-induced DNA damage and human cancer risk. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:630–637. doi: 10.1038/nrc1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alexandrov K, Margarita R, Geneste O, Castegnaro M, Camus AM, Petruzzelli S, et al. An inproved fluorometric assay for dosimetry of benzo(a)pyrene diol-epoxide-DNA adducts in smokers’ lung: comparisons with total bulky adducts and aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase activity. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6248–6253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gupta R, Earley K. 32P-adduct assay: comparative recoveries of structurally diverse DNA adducts in the various enhancement procedures. Carcinogenesis. 1988;9:1687–1693. doi: 10.1093/carcin/9.9.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Santella R. Immunological methods for detection of carcinogen-DNA damage in humans. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:733–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rundle A, Tang D, Hibshoosh H, Estabrook A, Schnabel F, Cao W, et al. The relationship between genetic damage from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in breast tissue and breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1281–1289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Romano G, Sgambato A, Boninsegna A, Flamini G, Curigliano G, Yang Q, et al. Evaluation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts in exfoliated oral cells by an immunohistochemical assay. Cancer Epidemiol Bio-markers Prev. 1999;8:91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Phillips DH, Farmer PB, Beland FA, Nath RG, Poirier MC, Reddy MV, Turteltaub KW. Methods of DNA adduct determination and their application to testing compounds for genotoxicity. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2000;35:222–233. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2280(2000)35:3<222::aid-em9>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Motykiewicz G, Malusecka E, Grzybowska E, Chorazy M, Zhang YJ, Perera FP, Santella RM. Immunohistochemical quantitation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts in human lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1417–1422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zenzes MT, Puy LA, Bielecki R, Reed TE. Detection of benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide-DNA adducts in embryos from smoking couples: evidence for transmission by spermatozoa. Mol Hum Reprod. 1999;5:125–131. doi: 10.1093/molehr/5.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rundle A, Tang D, Hibshoosh H, Schnabel F, Kelly A, Levine R, et al. Molecular epidemiologic studies of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts and breast cancer. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2002;39:201–207. doi: 10.1002/em.10048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rybicki BA, Rundle A, Savera AT, Sankey SS, Tang D. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8854–8859. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Martin FL, Cole KJ, Muir GH, Kooiman GG, Williams JA, Sherwood RA, et al. Primary cultures of prostate cells and their ability to activate carcinogens. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2002;5:96–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ramesh A, Inyang F, Knuckles ME. Modulation of adult rat benzo(a)pyrene (BaP) metabolism and DNA adduct formation by neonatal diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2004;56:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Feng Y, Jiang W, Hein DW. 2-Aminofluorene-DNA adduct levels in tumor-target and nontarget organs of rapid and slow acetylator Syrian hamsters congenic at the NAT2 locus. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1996;141:248–255. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tang D, Phillips DH, Stampfer M, Mooney LA, Hsu Y, Cho S, et al. Association between carcinogen-DNA adducts in white blood cells and lung cancer risk in the physicians health study. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6708–6712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]