Abstract

Connective tissue remodeling provides mammals with a rapid mechanism to repair wounds after injury. Inappropriate activation of this reparative process leads to scarring and fibrosis. Here, we studied the effects of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β blockade in vivo using the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-β inhibitor imatinib mesylate on tissue repair. After 7 days, healing of wounds was delayed with significantly reduced wound closure and concomitant reduction in myofibroblast frequency, expression of fibronectin ED-A, and collagen type I. Using a collagen type I transgenic reporter mouse, we showed that inhibiting PDGFR-β activation restricted the distribution of collagen-synthesizing cells to wound margins and dramatically reduced cell proliferation in vivo. By 14 days, treated wounds were fully closed. Blocking PDGFR-β signaling did not prevent the differentiation of myofibroblasts in vitro but potently inhibited fibroblast proliferation and migration. In addition, PDGFR-β inhibition in vivo was accompanied by abnormal microvascular morphogenesis reminiscent of that observed in PDGFR-β−/− mice with significantly reduced immunostaining of the pericyte marker NG2. Imatinib treatment also inhibited pericyte proliferation and migration in vitro. This study highlights the significance of PDGFR-β signaling for the recruitment, proliferation, and functional activities of fibro-blasts and pericytes during the early phases of wound healing.

Adult tissue repair is a complex process involving coordinated interactions between an array of cell types including leukocytes, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and epithelial cells. Despite the highly ordered sequence of events, the remodeling process is not functionally perfect because the end-product of repair is a scar.1,2 During wound healing, released growth factors promote a fundamental reprogramming of the fibroblast, resulting in dramatically increased synthesis, deposition, and formation of new connective tissue. Inappropriate activation of the repair process leads to excessive tissue scarring and fibrosis and forms the basis of many pathological disorders. Identifying the molecular cues that govern scar formation during wound healing is likely to have a significant impact on our understanding of pathological fibrosis.

One of the first growth factors deposited at the wound site by degranulating platelets is platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF).1 The three classic isoforms of PDGF exist as dimers and are composed of polypeptide A and B chains, forming the homodimers AA and BB and the heterodimer AB.3 Their physiological action is evoked by interaction with two specific cell receptor tyrosine kinases (α and β).4 Ligand binding results in receptor dimerization and autophosphorylation. The α receptor (PDGFR-α) binds all three PDGF isoforms, whereas the β receptor (PDGFR-β) preferentially binds PDGF BB.3 Recently, two new PDGF homodimers have been identified, PDGF-CC and PDGF-DD, which bind to PDGFR-α and PDGFR-β, respectively.5,6 Genetic analyses in mice have demonstrated that PDGF isoforms play critical roles in key aspects of mammalian embryogenesis.7,8 Analysis of PDGFR-α-, PDGF-A-, and PDGF-C-null mutants have demonstrate that PDGFR-α signaling is essential for palatogenesis and the correct patterning of somites and mesodermal tissue.9,10 PDGF-B- and PDGFR-β-null mutants die in utero from widespread hemorrhaging attributable to impaired recruitment of mural pericytes and smooth muscle cells to nascent blood vessels.11 In vitro systems have revealed the signal transduction pathways evoked by PDGF-α and -β receptors are similar, but they differ subtly with respect to interactions with specific SH2 domain proteins, which may explain their differential effects on target cells.12 Although both receptors evoke mitogenic signals, the β-receptor is the more potent transducer of cell motility.3 In contrast to PDGFR-β, stimulation of PDGFR-α inhibits chemotaxis of fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells.13 There are also differences between the receptors and their influence on the actin filament system. Both receptors stimulate edge ruffling and loss of stress fibers, but only the β-receptor mediates the formation of circular actin structures on the cell surface.12

Because of the embryonic lethality of PDGFR-β knockout mice,14 our understanding of the role of PDGFR-β in adult tissue repair and fibrosis has been based primarily on in vitro data and analyses involving the local administration of PDGF ligand.3 Cultured dermal fibroblasts lacking functional PDGFR-β show impaired mitosis and complete inhibition of migration with decreased phosphorylation of Akt, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2, and c-Jun NH2-terminal protein kinase (JNK), but not p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK).15 The addition of exogenous PDGF-BB increases fibroblast proliferation and migration into the wound, indirectly leading to both increased extracellular matrix production and wound tensile strength.16,17 In addition, overexpression of PDGFR-β within lesional connective tissue compartments has been noted in several fibrotic disorders including systemic sclerosis18 and dermal scarring.19 Although these analyses demonstrate that exogenous PDGF is capable of stimulating connective tissue cell proliferation in vivo and enhancing tissue repair, they do not tell us how the overexpression of endogenous PDGFR-β contributes to fibrogenesis. This has been partially addressed by studies of PDGFR-β chimeric mice, which have, however, provided tantalizing glimpses of the requirement for PDGFR-β expression by fibroblasts and microvascular cells during wound healing.20 Although these studies predict a requirement for PDGFR-β signaling in fibroblasts and endothelial cells during tissue repair, they provide no data on the precise functional role of PDGFR-β in vivo. To gain a greater appreciation of the role of endogenous PDGFR-β during adult tissue repair, we have assessed the functional consequences of selective inhibition of PDGFR-β in vivo using imatinib mesylate in excisional wound healing and in vitro using cultures of fibroblasts and pericytes.

Materials and Methods

Animals

In this study, we used a transgenic mouse line harboring a construct of the mouse collagen 1α2 promoter containing 17 kb 5′ of the transcription start site, including the far upstream enhancer region, fused to luciferase and β-galactosidase (LacZ) reporter genes.21

Wound-Healing Experiments

All animal protocols were approved by the local animal ethics committee at University College London. Six- to 8-week-old female mice were anesthetized with avertin (500 mg/kg). The dorsum was shaved and cleaned with alcohol. Four equidistant 4-mm full-thickness excisional wounds were made on either side of the midline of the mouse. Wound diameter was measured, and after sacrifice, wounds were photographed and harvested at days 3, 7, 10, and 14 after wounding and processed for histology, immunohistochemistry, and protein extraction. For PDGFR-β blockade, imatinib was prepared as previously described22 and administered intraperitoneally at 75 mg/kg per day.

Histology

Histological sections were prepared from wound tissue fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Four-μm sections were stained with either hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Masson’s trichrome. All sections were viewed on an Axioskop Mot Plus microscope with an Axiocam digital camera in combination with Axiovision software (Carl Zeiss, Welwyn Garden City, UK).

Antibodies

The monoclonal antibodies 1A4 against α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and 3E2 against ED-A FN were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The anti-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) antibody BU 1/75 was obtained from Abcam plc (Cambridge, UK). Anti-CD31 antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences Transduction Laboratories. Anti-NG2 antibody and anti-collagen type I antibodies were obtained from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA). NG2 is a membrane-spanning chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan that is expressed by microvascular pericytes.23 Biotinylated and Texas Red-conjugated antibodies were obtained from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA).

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry, wounds were excised and embedded in OCT and immediately snap-frozen in isopentane cooled by liquid nitrogen and subsequently stored at −70°C before cryosectioning. Serial frozen sections (5 μm) were cut on a cryostat, air-dried, and then stored at −80°C before use. Sections were fixed in ice-cold acetone and then blocked with normal serum from the appropriate species and incubated with primary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. Endogenous peroxidase was exhausted by incubation with H2O2 at room temperature for 15 minutes in the dark. After washing, sections were incubated with a biotinylated secondary antibody (7.5 μg/ml) diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 minutes, rinsed, and incubated with Vectastain avidin/biotin complex conjugated with horseradish peroxidase for 30 minutes (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK). After washing, sections were visualized using 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole. Sections were then washed in tap water, counterstained with hematoxylin, and aqueously mounted with Crystal-Mount (Biomeda, Foster City, CA). Sections were viewed and photographed on a Zeiss Axioskop 2 mot plus microscope. Controls included an exchange of primary antibodies with isotype-matched control antibodies.

BrdU Labeling

Mice were injected with 2 ml of BrdU-labeling reagent/100 g mouse weight i.p. (RPN 201; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Chalfont, St. Giles, UK) 2 hours before they were sacrificed. Skin samples were fixed, embedded, and sectioned as previously described. After dewaxing, the sections were microwaved in citrate buffer, pH 6, for 10 minutes and then placed in 4 N HCl for 30 minutes at 37°C. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C with an anti-BrdU antibody. Slides were then washed in PBS and incubated with a biotinylated anti-rat secondary antiserum, washed, and then treated as above with Vectastain avidin/biotin complex reagent. Sections were visualized with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole, counterstained, and mounted.

Terminal dUTP Nick-End Labeling (TUNEL) Staining of Tissue Sections

Paraffin-embedded sections were dewaxed and taken to water. Sections were then treated with freshly prepared proteinase K (20 μg/ml) for 15 minutes at room temperature. After 3 × 5-minute washes in PBS, the sections were incubated with a mixture of working-strength terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) and digoxigenin-labeled nucleotide triphosphates (Chemicon) for 1 hour at 37°C. The sections were then washed in PBS and incubated with a Texas Red-conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody for 30 minutes at room temperature. The sections were then washed in PBS and nuclear counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The number of apoptotic cell nuclei was then counted in 10 fields of vision (×40 objective) and calculated as a percentage of total cells per field of view as determined by DAPI staining.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were permeabilized for 5 minutes with 0.2% Triton X-100 (TX-100) in 3% paraformaldehyde and fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde/PBS for 10 minutes. The anti-α-SMA antibody was used to identify myofibroblasts. The cells were visualized with a secondary anti-mouse Texas Red conjugate and counterstained with DAPI to visualize cell nuclei.

Image Analysis

Images were captured using a ×40 Plan Neofluar lens (NA and so forth) and analyzed using KS400 software (Imaging Associates, Bicester, UK). After image capture and segmentation, the total number of immunopositive cells was expressed as a percentage of the total number of cells in each field of view. Significance was evaluated using the Student’s t-test with a P value of <0.05 considered as statistically significant.

β-Galactosidase Expression and Distribution

Levels of β-galactosidase transgene expression were assayed using a β-galactosidase chemiluminescent reporter gene assay system (TROPIX; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Wound tissue was weighed and homogenized according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The same samples were measured for protein content using the BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). To assess the spatial distribution of the β-galactosidase transgene, one sample of wound tissue from each animal was fixed with 0.2% glutaraldehyde, 2% formalin in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer, pH 7.3, containing 2 mmol/L MgCl2 and ethylene glycol bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid for 45 minutes. Samples were then washed three times for 30 minutes each in the same phosphate buffer with 0.1% sodium deoxycholate and 0.2% Nonidet P-40 and stained overnight at room temperature in the dark with 1 mg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyo-β-d-galactoside solution (X-gal) containing 5 mmol/L potassium ferrocyanide and 5 mmol/L potassium ferricyanide. For histological analysis, wound samples were then embedded in paraffin, and 4-μm sections were cut, dewaxed, and counterstained with eosin.

Cell Culture and Reagents

AG01518 foreskin fibroblasts (Coriell Institute for Medical Research, Camden, NJ) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, sodium pyruvate, and glutamine. Placental pericytes were isolated and identified as previously described.24 For serum starvation and treatments, cells were incubated in medium containing sodium pyruvate, glutamine, and serum replacement factor (Sigma), which was added to DMEM to generate a serum-free medium. To determine the effect of imatinib treatment on myofibroblast formation, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was added daily to the cells at a concentration of 2 ng/ml for 5 days. For inhibition experiments, cells were preincubated 30 minutes before the addition of TGF-β with imatinib at a concentration of 2 μmol/L.

In Vitro Wound Closure Assay

In vitro wound closure assays were performed by creating clear lines in a confluent cell monolayer with a sterile plastic pipette tip. The migration of the cells into the cleared spaces was monitored throughout time and photographed. To investigate cell migration, contraction of relaxed collagen gels was assessed. Twenty-four-well tissue culture plates were precoated with sterile 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS (2 ml/well) to prevent the gels from becoming bound to the plastic. Gel contraction assays were performed by allowing 2 ml of DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1.0 mg/ml bovine type I collagen (Vitrogen 100; Nutacon, Leimuiden, The Netherlands), and 8 × 104 fibroblasts/pericytes to form a gel for 3 hours at 37°C before releasing the gels from the dish. Contraction of the gel was quantified by loss of gel weight and decrease in gel diameter throughout a 24-hour period. The effect of imatinib on tethered gel contraction was assessed as previously described.25 In brief, the tissue culture plates were not precoated with bovine serum albumin, allowing the gels to adhere to the sides of the tissue culture dish. The gels were then treated with DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) or 10 ng/ml PDGF-BB. The gels were maintained for a period of 48 hours, allowing mechanical tension to develop. To initiate contraction, the gels were gently released from the culture dish using a sterile pipette tip and the contraction monitored throughout a 24-hour period. For inhibition experiments, cells were preincubated in the presence of imatinib mesylate for 30 minutes before initiation of the assay. Significance was evaluated using the Student’s t-test with a P value of <0.05 considered as statistically significant.

Cell Proliferation

Cell proliferation was assessed using a methylene blue assay.26 Cells were counted and plated at 1000 cells/well in a 96-well tissue culture plate. Cells were serum-starved for 48 hours and treated with PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml) for 48 hours. For inhibition experiments, cells were preincubated with imatinib at a concentration of 2 μmol/L for 30 minutes before the addition of PDGF-BB. At the end of the incubation period, cells were washed in PBS and fixed using 10% neutral buffered formalin. Plates were incubated with 100 ml of methylene blue, washed in 0.01 mol/L borate buffer, and absorbance was measured at 650 nm.

Results

Imatinib Treatment Impairs Wound Closure

Excisional wounds were made on the back of 6- to 8-week-old collagen transgenic mice (Figure 1A). After 3 days, the wound area of control mice was reduced by 40% of original size and 70% after 7 days (Figure 1, B and C). In contrast, imatinib-treated wounds were reduced by 20% after 3 days and 50% after 7 days (Figure 1, D and E). These differences were statistically significant between 3 and 7 days after wounding (P < 0.01) (Figure 1J). By day 10, the differences in wound area were no longer statistically significant, and by day 14, wounds had closed in both sets of animals.

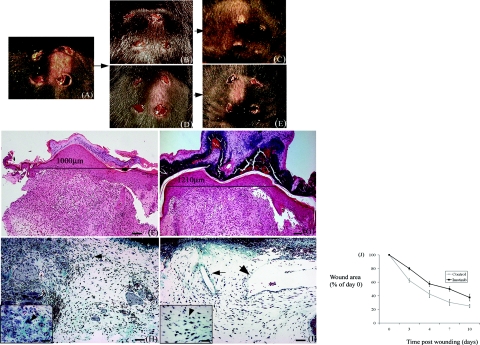

Figure 1.

Wound healing is impaired in mice treated with imatinib. A: Punch wounds (4 mm3) were made on the back of anesthetized mice. After 3 days, wound diameters are noticeably smaller in control animals (B) in comparison with imatinib-treated animals (D). After 7 days, wound diameters in control wounds (C) are clearly reduced compared with imatinib-treated wounds (E). Analysis of sections stained with H&E confirmed that after 7 days, distance between wound margins was greater in imatinib-treated animals (G) compared with control animals (F). Staining of sections with Masson’s trichrome confirmed that granulation tissue in treated animals was poorly formed and relatively hypocellular (I, arrows) compared with control animals (H, arrows). Granulation tissue in control animals was characterized by the formation of small blood vessels (H, inset, arrowhead), which were not present in imatinib-treated wounds (I, inset, arrowhead). Quantification of wound diameter throughout 10 days after injury. Results represent the mean ± SEM. Between 3 and 7 days after wounding, the difference in wound diameter was significant (P < 0.05). Scale bars = 100 μm (F, G); 50 μm (H, I); 10 μm (insets).

Histological analysis of sections stained with H&E confirmed that 7 days after wounding, imatinib-treated wounds displayed reduced wound contraction compared with controls (Figure 1, F and G). Wound morphology was assessed by Masson’s trichrome staining. In control animals after 3 days, wounds were characterized by cell migration from the wound margins and the formation of small blood vessels within the provisional wound matrix (Figure 1H). In contrast, the wound tissue in treated mice was relatively hypocellular, and blood vessels were abnormally large and distended (Figure 1I). At day 7, treated wounds were still significantly larger than controls with reduced cellular and microvascular density. After 14 days, treated wounds had contracted and were characterized by acellular scar tissue (unpublished data).

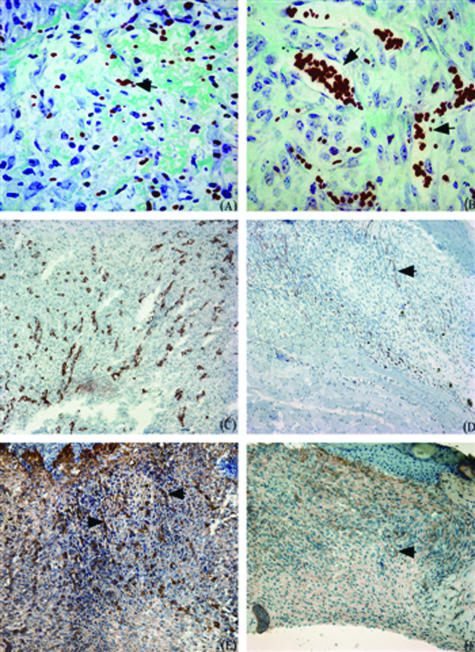

Reduced Cell Proliferation in Imatinib Mesylate-Treated Animals

BrdU incorporation was used to identify proliferating cells. In control animals, 3 days after wounding, the majority of BrdU-labeled cells were located at the wound margins and in the basal keratinocyte layer (Figure 2, A and C). The addition of imatinib resulted in a substantial decrease in BrdU incorporation after 3 days with little or no evidence of cell proliferation (Figure 2, B and D). In control animals, BrdU immunostaining was evident in pericytes (Figure 2C, inset) but was absent in pericytes of imatinib-treated wounds (Figure 2D, inset). After 7 days, in control animals, BrdU-labeled cells were more uniformly distributed throughout the granulation tissue (Figure 2E). In imatinib-treated wounds, BrdU-labeled cells were more evident than after 3 days and were located throughout the wound tissue; however, overall numbers were still reduced in comparison with control tissue (Figure 2F). Quantification of the number of positively stained cells using image analysis confirmed that the reduction in BrdU incorporation after 3 and 7 days was statistically significant (P < 0.005), (Figure 2G). The principal PDGF-BB-responsive cells in the dermis are fibroblasts and pericytes. Therefore, we used an in vitro approach to determine whether fibroblasts and pericytes were sensitive to imatinib treatment. PDGF-BB induced a robust mitogenic response in both cultured pericytes and fibroblasts (Figure 2, H and I). PDGF-BB-induced proliferation was significantly inhibited by imatinib treatment (P < 0.005), (Figure 2, H and I). Serum-induced mitogenesis of pericytes and fibroblasts was also significantly reduced by imatinib (Figure 2, H and I), confirming that PDGF-BB is a principal mitogenic serum factor for fibroblasts and pericytes.

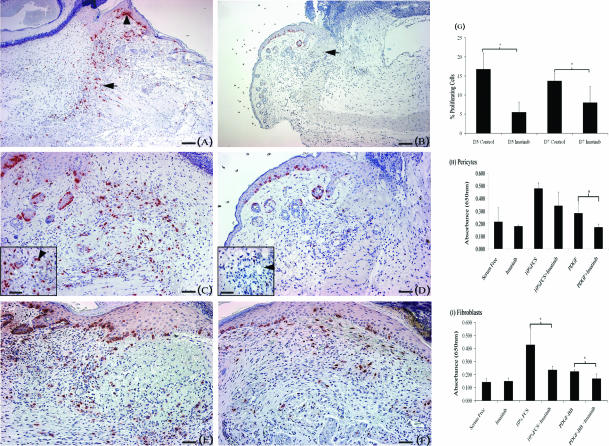

Figure 2.

Cell proliferation is inhibited in imatinib-treated mice. Mice were injected with BrdU 2 hours before sacrifice. Sections were subsequently stained with an anti-BrdU antibody. Three days after injury, immunostaining for BrdU was significantly increased in control animals (A, C) compared with treated animals (B, D). In control animals, BrdU immunostaining was predominant at the wound margins (A, arrow), which was significantly reduced in imatinib-treated animals (B, arrow). In control animals, BrdU immunostaining was present in pericytes (C, inset, arrowhead) in contrast to imatinib-treated animals (D, inset, arrowhead). E and F: After 7 days, BrdU immunostaining was present in the granulation tissue of both control and imatinib-treated animals. G: Quantification of BrdU-stained cells confirming that imatinib treatment produced a significant reduction in cell proliferation after 3 and 7 days. Results represent the mean ± SD. *P < 0.005. Inhibition of pericyte (H) and fibroblast (I) proliferation by imatinib was confirmed by in vitro analyses. Ten percent of FCS and PDGF-BB-induced stimulation of pericyte and fibroblast proliferation was inhibited by treatment with imatinib (2 μm). Results represent the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05. Scale bars = 100 μm (A, B); 50 μm (C–F); 10 μm (insets).

Imatinib Treatment Does Not Affect Apoptosis in Vivo

Imatinib treatment resulted in reduced cellularity in the granulation tissue. Therefore, the role of imatinib on apoptotic cell death was investigated to establish whether increased apoptotic cell death was responsible for the hypocellularity of imatinib-treated wounds. Analysis of day 7 wound sections by TUNEL staining demonstrated that apoptotic nuclei were evenly distributed throughout control (Figure 3A) and imatinib-treated wounds (Figure 3C). Counting of apoptotic cell nuclei revealed no significant difference between control and imatinib-treated wounds (Figure 3E). The number of cell nuclei in control and imatinib-treated wounds was counted in 10 fields of view (×40 objective) and compared. This confirmed that imatinib-treated wounds contained 10% fewer cells per field of view compared with control wounds.

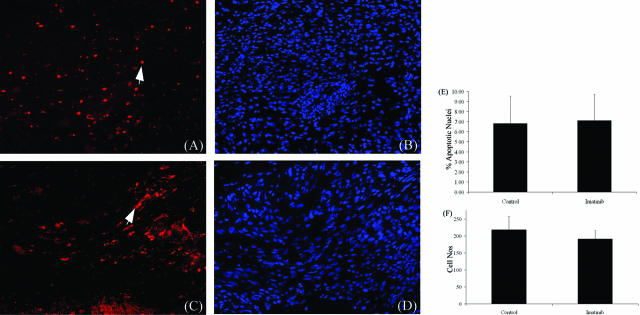

Figure 3.

Imatinib treatment does not affect apoptotic cell death in vivo. Apoptotic cell death in day 7 wounds was assessed by TUNEL staining. Apoptotic nuclei (arrows, red) were detected in both control (A) and imatinib-treated wounds (C). Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (B, D). Analysis of the percentage of apoptotic cell nuclei in control and imatinib-treated sections revealed no significant difference (E) (P = 0.8). Quantification of cell nuclei revealed 10% fewer cells in imatinib-treated wounds compared with controls (F). Data shown are mean ± SD. Original magnifications, ×20.

Imatinib Treatment Impairs Motility of Fibroblasts and Pericytes in Vitro

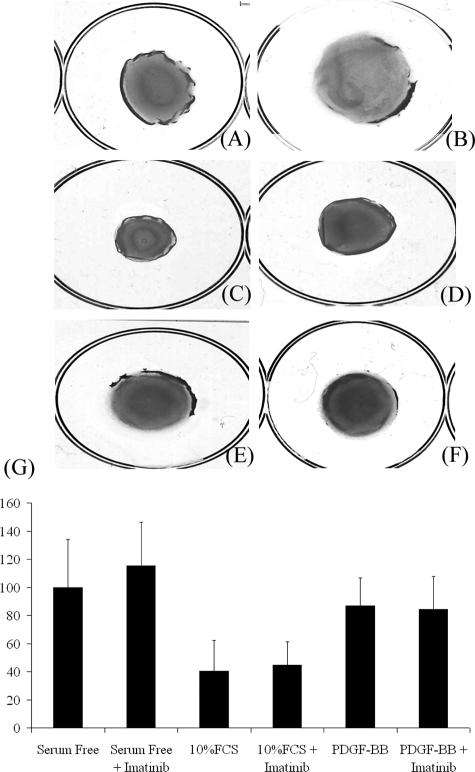

We hypothesized that the hypocellularity of imatinib-treated wounds was due in part to inhibition of PDGF-BB-mediated motility. To confirm this we performed a series of in vitro analyses investigating fibroblast and pericyte migration using scratch wounds and relaxed collagen gels. In response to PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml), both fibroblasts and pericytes had completely closed scratch wounds after 72 hours (Figure 4, D and H). The addition of imatinib resulted in marked inhibition of fibroblast and pericyte migration (Figure 4, E and I). Migration stimulated by DMEM containing 10% FCS (Figure 4, B and F) was also inhibited by imatinib treatment, indicating that PDGF-BB is a major serum factor in promoting pericyte and fibroblast migration (Figure 4, C and G). We assessed the ability of PDGF-BB to stimulate pericytes and fibroblasts to contract a relaxed collagen gel, a process dependent on the tractional forces of migrating cells. Cells were incubated for 24 hours in the presence or absence of PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml). Both cell types when incubated with PDGF-BB contracted their gels significantly more than cells incubated with vehicle alone (P < 0.05) (Figure 4I). PDGF-BB induced gel contraction was significantly inhibited by imatinib treatment, confirming the impairment of cell migration (P < 0.01) (Figure 4J).

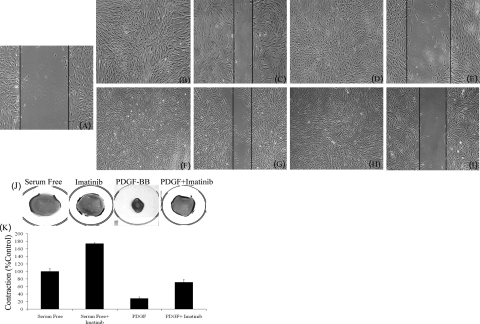

Figure 4.

Imatinib treatment impairs migration of pericytes and fibroblasts in vitro. A: Scratch wounds were made in confluent cell monolayers. In response to both 10% FCS and 10 ng/ml PDGF-BB, fibroblasts (B, D) and pericytes (F, H) completely fill a scratch wound after 72 hours. The addition of imatinib (2 μm) completely abrogates migration induced by both 10% FCS and PDGF-BB in fibroblasts (C, E) and pericytes (G, I). Impairment of cell migration was confirmed and quantified using free-floating collagen matrices. Representative images of pericyte-seeded gels are shown. Pericytes were seeded into a collagen gel matrix, and after gel polymerization, the gel was detached from the tissue culture plate and incubated in the presence or absence of PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml). J: Pericyte contraction of gels in response to PDGF-BB is inhibited in the presence of imatinib. K: Quantification of gel weight after contraction. Results represent the mean ± SD.

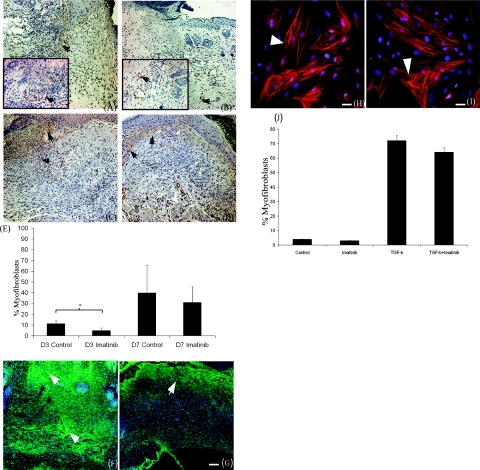

Imatinib Treatment Impairs Myofibroblast Formation in Vivo

PDGF-BB is known to be a potent mitogen for myofibroblasts,27 therefore we compared the expression of myofibroblast markers such as ED-A FN and α-SMA. At 3 days after wounding, myofibroblasts in treated wounds were significantly reduced in number compared with control animals (Figure 5, A and B). α-SMA immunostaining in imatinib-treated wounds was restricted predominantly to microvessels (Figure 3B), whereas in control animals, immunostaining was observed in interstitial myofibroblasts at the wound margins (Figure 5A). By 7 days after wounding, myofibroblasts had appeared in treated wounds and were primarily located at the epidermal-dermal junction and surrounding microvessels (Figure 5D). In control tissue, α-SMA-positive myofibroblasts appeared to be more uniformly distributed throughout the granulation tissue (Figure 5C). Using image analysis to count the number of positively stained cells, the reduction in myofibroblast numbers 3 days after wounding was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.01) (Figure 5E), whereas after 7 days, the reduction in myofibroblast numbers did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.13) (Figure 5E). By 14 days, α-SMA expressing myofibroblasts were no longer detectable in either control or imatinib-treated wounds (unpublished data). Imatinib treatment also resulted in decreased expression of the ED-A splice variant of fibronectin (ED-A FN). In treated wounds, ED-A FN was confined to the papillary dermal layer adjacent to the epidermis (Figure 5G). In contrast, ED-A FN was distributed throughout the granulation tissue in control wounds (Figure 5F). To investigate the mechanism by which imatinib treatment impaired myofibroblast formation, we treated dermal fibroblasts in vitro with TGF-β for 4 days to promote myofibroblast differentiation. After 4 days of treatment with TGF-β, 72% of the cells contained α-SMA+ve stress fibers (Figure 5H), compared with 4% of treated with vehicle alone (unpublished data). The addition of imatinib did not affect α-SMA stress fiber formation either qualitatively or quantitatively (Figure 5, I and J), suggesting that the reduction in myofibroblast numbers in vivo does not result from an inhibition of TGF-β-mediated myofibroblast formation.

Figure 5.

Imatinib treatment delays the appearance of myofibroblasts. A: Three days after injury, α-SMA immunostaining is present in myofibroblasts in the wound margins of control animals (arrow). B: In imatinib-treated animals, α-SMA immunostaining is restricted to microvessels (arrow). After 7 days, α-SMA immunostaining is present throughout the granulation tissue of control (C, arrows) and present in imatinib-treated wounds, particularly at the epidermal/dermal junction (D, arrows). Quantification of the number α-SMA-expressing myofibroblasts by image analysis confirmed a significant reduction in myofibroblast numbers in imatinib-treated animals 3 days after injury. E: After 7 days, myofibroblast numbers were still lower in imatinib-treated animals; however, the difference was not significant. Expression of ED-A FN was also reduced as a result of imatinib treatment (G, arrow) compared with control tissue (F, arrows). Results represent the mean ± SD. *P < 0.01. TGF-β (2 ng/ml) treatment of cultured fibroblasts produced prominent α-SMA stress fibers (H, arrowhead), which was not inhibited by imatinib treatment (I, arrowhead). J: Quantification of myofibroblast numbers after TGF-β and imatinib treatment. Results represent the mean ± SD. Scale bars = 50 μm (A–G); 25 μm (H, I).

Imatinib Mesylate Does Not Block Serum-Induced Contraction of Tethered Collagen Gels

We then assessed whether imatinib treatment affected the contraction of tethered collagen by fibroblasts. In this system, cells are subject to mechanical tension as the gels are attached to the culture dish. Using this system, the contraction of tethered collagen gels was stimulated by DMEM containing 10% FCS. However, treatment with PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml) was found to have no significant stimulatory effect (Figure 6). Serum-induced gel contraction was not inhibited by the actions of imatinib (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Imatinib mesylate does not block serum-induced contraction of tethered collagen gels. The ability of fibroblasts to contract tethered collagen lattices was assessed. Cells were seeded into tethered collagen gels. Mechanical tension was generated throughout a 48-hour period after which the gels were released. DMEM containing 10% FCS (C) stimulated contraction in comparison to serum-free DMEM (A) and PDGF-BB (10 ng/ml) (E). Imatinib did not affect contraction by serum-free DMEM (B), 10% FCS (D), and PDGF-BB (F). G: Quantification of gel weight after contraction. Results represent the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05.

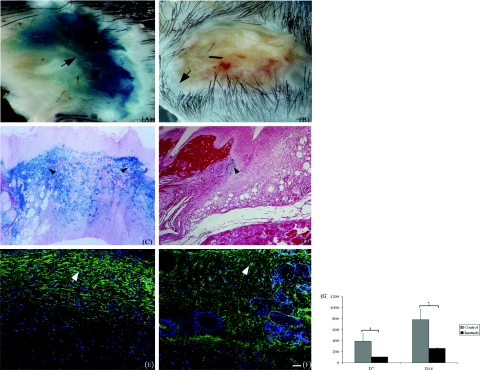

Imatinib Mesylate Treatment Results in Diminished Collagen Type I Biosynthesis

PDGF indirectly stimulates collagen type I biosynthesis by stimulating proliferation and migration of activated fibroblasts. To determine whether collagen type I biosynthesis was affected by blockade of PDGFR-β signaling, we used a transgenic mouse harboring a 17-kb fragment of the collagen 1α2 upstream enhancer fused to a β-galactosidase (Lac-Z) reporter gene.21 The expression profiles and distribution of the 17-kb fragment during adult wound healing have been previously defined and demonstrated to be a marker of endogenous gene expression.28 After 7 and 14 days, collagen transgene expres-sion was significantly reduced in treated animals (P < 0.01) (Figure 7G). In control samples, transgene-expressing cells were extensively located throughout day 7 granulation tissue (Figure 7, A and C). In treated wounds, transgene expression was noticeably less pronounced and was restricted to the wound margins (Figure 7, B and D). To confirm the reduction in collagen biosynthesis at the protein level, wound sections were probed with an antibody against collagen type I. After 14 days, expression of collagen type I was reduced in imatinib-treated wounds (Figure 7F) compared with control wounds (Figure 7E), mirroring the expression of the transgenic reporter construct.

Figure 7.

Collagen type I gene promoter activity is reduced in imatinib-treated animals. Seven days after injury, wounds were excised from mice and stained with 1 mg/ml X-gal. Control wounds show uniformly intense X-gal staining (A, arrow), whereas staining in tissue from imatinib-treated mice was significantly weaker and confined to the wound margins (B, arrow). C: In histological sections, X-gal staining could be observed in fibroblastic cells throughout the granulation tissue (arrowheads). D: In sections from imatinib-treated animals, relatively fewer blue cells were present and were restricted to the wound margins (arrowhead). G: Imatinib-mediated reduction in collagen transgene activity was confirmed by quantification of transgene activity in whole wounds. Results represent the mean ± SD. *P < 0.01. Immunofluorescence staining of 14-day-old wounds confirming that expression of collagen protein was concordantly reduced in imatinib-treated wounds (F, arrow) relative to control tissue (E, arrow). Scale bar = 50 μm.

Imatinib Mesylate Treatment Impairs Angiogenesis during Wound Healing

The importance of PDGFR-β in regulating pericyte recruitment during angiogenesis has been well documented.11 We therefore hypothesized that imatinib treatment would impair vascular formation during wound healing. Masson’s trichrome staining of wound sections demonstrated abnormal microvascular morphology as a result of imatinib treatment. Microvessels were fewer and were abnormally large and distended compared with those in control wounds (Figure 8, A and B). Moderately reduced neovascularization was confirmed by immunostaining for CD31, which was reduced in the granulation tissue of imatinib-treated wounds (Figure 8, C and D). Using an antibody against NG2, a marker for pericytes, reduced immunostaining was discovered in imatinib-treated wounds compared with control tissue (Figure 8, E and F). Interestingly, the degree of vascular disruption varied between wounds. The reasons for this are unclear.

Figure 8.

Imatinib treatment impairs angiogenesis during wound healing. Masson’s trichrome staining demonstrating the presence of abnormally dilated microvessels in day 7 granulation tissue of imatinib-treated animals (B, arrows) compared with normal microvascular architecture in control wounds (A, arrows). Cryosections from control and imatinib-treated wounds were stained with antibodies recognizing endothelial cells (CD31) and pericytes (NG2). In control wounds, 7 days after injury, immunostaining for both CD31 (C, arrows) and NG2 (E, arrows) was prominent throughout the granulation tissue. In imatinib-treated wounds, immunostaining for both CD31 (D, arrows) and NG2 (F, arrows) was comparatively reduced. Scale bar = 25 μm.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that imatinib impairs the onset of cutaneous wound healing and collagen biosynthesis in vivo and pericyte and fibroblast activation in vitro. Besides PDGFR-β, imatinib is also known to inhibit the c-abl and c-kit tyrosine kinases.29 Therefore, the possibility that inhibition of these kinases contributes to the impairment of wound healing and collagen biosynthesis cannot be excluded. However, although c-abl was recently identified as a potential mediator of TGF-β activity,30 in our current study we found imatinib to have no effect on the TGF-β-induced formation of myofibroblasts in vitro, nor were we able to detect in vivo any previously reported characteristics of impaired TGF-β signaling during wound healing such as accelerated re-epithelialization.31 Furthermore, to our knowledge, there is no evidence that c-kit directly mediates fibroblast and pericyte proliferation and migration, which taken together support our hypothesis that the effect of imatinib on these cells is attributable to PDGFR-β blockade. The effects of PDGFR-β signaling on mesenchymal cell proliferation and migration have been well documented in vitro.3 However, because of the embryonic lethality of both the PDGF-B chain and PDGFR-β-null mutants, much remains unknown regarding the postnatal role of PDGFR-β in vivo. The data presented in our current study clearly support the hypothesis that in vivo PDGFR-β is a key mitogen and motogen for both fibroblasts and pericytes during the early stages of tissue repair. Between 3 and 7 days after wounding, cell proliferation was significantly reduced in the granulation tissue of imatinib-treated wounds. In control tissue after 3 days, proliferating cells were located predominantly in the wound margins and in the basal epidermis. Reduced cell proliferation in imatinib-treated wounds was also associated with interstitial fibroblasts and microvascular cells.

A further aspect of imatinib treatment was a significant reduction in early wound closure. Wound closure is thought to be initiated by tractional forces generated by fibroblasts migrating into newly forming granulation tissue.32 As the wound closes, mechanical tension develops, which combined with the actions of TGF-β and ED-A FN induces the formation of myofibroblasts, which then contract the wound.33 Because the granulation tissue of imatinib-treated wounds was generally hypocellular compared with controls, it is plausible that the failure to initiate wound closure stems from inhibition of PDGFβR-mediated recruitment of fibroblasts into the wound. The subsequent reduction in tractional force generation could conceivably result in reduced wound closure. Using two independent assays of cell migration, scratch wound assays and contraction of relaxed collagen gels, we were able to show that the in vitro migration of pericytes and fibroblasts was impaired by imatinib treatment. Given that imatinib-treated wounds were hypocellular compared with control wounds, we also assessed the effect of imatinib treatment on apoptosis by TUNEL staining. There was no difference in the number of apoptotic nuclei in control and imatinib-treated wounds, indicating that reduced cell proliferation and migration were the principle causes of the reduced cell numbers in imatinib-treated wounds. This is in agreement with a recent analysis of synovial fibroblasts showing that imatinib blocked proliferation without affecting apoptosis.34

Imatinib treatment resulted in a reduction in the number of α-SMA-expressing myofibroblasts and reduced expression of ED-A FN, which is crucial for myofibroblast formation.35 After 3 days, α-SMA immunostaining, denoting the presence of myofibroblasts, was present in control tissue but absent in treated tissue. By 7 days, the number of myofibroblasts in treated wounds was still reduced; however, the difference was no longer statistically significant. During wound healing the differentiation of myofibroblasts from fibroblasts is stimulated by mechanical tension generated as wound margins are reapproximated.32,33 Therefore, a reduction in cell migration and recruitment would result in a smaller pool of cells from which myofibroblasts could be formed. Moreover, a loss of tractional forces would delay the generation of mechanical tension, which is an essential requirement for myofibroblast formation. We found that imatinib treatment had no effect on the TGF-β-mediated differentiation of myofibroblasts in vitro, supporting the idea imatinib reduces myofibroblast numbers by impairing fibroblast migration and proliferation rather than by affecting the process of myofibroblast differentiation from fibroblasts. It has been proposed that imatinib attenuates the fibrotic response by inhibiting TGF-β-mediated signaling via a novel non-Smad-dependent pathway.22,30 Although further studies are required to confirm this, our data demonstrate that the induction of the myofibroblast phenotype by TGF-β in vitro is not affected by imatinib treatment. We also studied the effects of imatinib on fibroblast contraction of tethered collagen gels. This system allows for the contraction of collagen matrices under mechanical tension and therefore models the contraction of granulation tissue by myofibroblasts. In our hands, PDGF-BB did not significantly promote tethered gel contraction by fibroblasts. However, cells incubated with 10% FCS produced a robust contraction that was not affected by imatinib. These results indicate that blockade of PDGFR-β blocks cell recruitment and the generation of tractional forces by migrating cells, which in turn impairs initial wound closure.

Another aspect of imatinib-treated wounds was reduced microvascular density and the presence of abnormally dilated and distended microvessels. Moreover, immunostaining for NG2, a pericyte marker,23 was reduced in imatinib-treated wounds. Similarly distended microvessels have been recorded in PDGFR-β and PDGF-B chain knockout mice14,36 with subsequent studies confirming that these microaneurysms were caused by a failure to adequately recruit pericytes to nascent capillaries.11,37 Using an in vitro approach, imatinib treatment was shown to impair significantly the migration and proliferation of cultured pericytes in response to both PDGF-BB and serum. Our findings mirror studies showing impaired microvascular formation in response to PDGFR-β inhibition in the vasculature of tumors.38,39 It was recently demonstrated that during tumor formation that the differentiation of pericytes from bone marrow-derived progenitor cells is PDGFR-β-dependent.40 Although this mechanism of pericyte recruitment has yet to be demonstrated in wound healing, it is clear that PDGFR-β signaling is central to the expansion and recruitment of resident pericytes in the adult.

Our studies also demonstrated that PDGFR-β inhibition results in reduced collagen biosynthesis during wound healing. The addition of exogenous PDGF-BB during excisional wound healing has been shown to increase the synthesis of provisional matrix components such as fibronectin and is thought to indirectly augment collagen biosynthesis by promoting the recruitment of fibroblasts.41 PDGF-BB has been shown to have no direct stimulatory affect on type I collagen gene expression in cultured fibroblasts.42 Therefore, the observed reduction in collagen biosynthesis resulting from imatinib treatment may stem directly from reduced fibroblast proliferation and recruitment.

The potential of PDGFR-β blockade as a potential anti-fibrotic strategy has been previously validated in studies of experimentally induced pulmonary and renal fibrosis.22,30,43 Interestingly, a number of studies have demonstrated that in fibrotic tissue increased PDGFR-β expression localizes to pericytes. Our data demonstrate that microvascular pericytes are a key target cell for PDGF-B during tissue repair, and further studies are merited to determine its precise functions in the development of fibrosis. In conclusion, we have shown that endogenous PDGFR-β signaling is critical in initiating the tissue repair process by stimulating the expansion and recruitment of fibroblasts and pericytes, and this may be significant in fibrotic disorders characterized by PDGFR-β overexpression.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to David Abraham, Centre for Rheumatology and Connective Tissue Disease, Department of Medicine (Hampstead Campus), Royal Free and University College Medical School, Rowland Hill St., London NW3 2PF, UK. E-mail: d.abraham@medsch.ucl.ac.uk.

Supported by The Arthritis Research Campaign, the Raynaud’s and Scleroderma Association, the Scleroderma Society, the Jean Shanks Foundation (UK), The Scleroderma Research and Development Action Committee, the Swedish Society for Medical Research, The Rosetrees Charitable Trust, and The British Skin Foundation.

References

- Martin P. Wound healing—aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science. 1997;276:75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayat A, McGrouther DA, Ferguson MW. Skin scarring. BMJ. 2003;326:88–92. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7380.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldin CH, Westermark B. Mechanism of action and in vivo role of platelet-derived growth factor. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1283–1316. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldin CH, Backstrom G, Ostman A, Hammacher A, Ronnstrand L, Rubin K, Nister M, Westermark B. Binding of different dimeric forms of PDGF to human fibroblasts: evidence for two separate receptor types. EMBO J. 1988;7:1387–1393. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02955.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Ponten A, Aase K, Karlsson L, Abramsson A, Uutela M, Backstrom G, Hellstrom M, Bostrom H, Li H, Soriano P, Betsholtz C, Heldin CH, Alitalo K, Ostman A, Eriksson U. PDGF-C is a new protease-activated ligand for the PDGF alpha-receptor. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:302–309. doi: 10.1038/35010579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsten E, Uutela M, Li X, Pietras K, Ostman A, Heldin CH, Alitalo K, Eriksson U. PDGF-D is a specific, protease-activated ligand for the PDGF beta-receptor. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:512–516. doi: 10.1038/35074588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betsholtz C. Insight into the physiological functions of PDGF through genetic studies in mice. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:215–228. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch RV, Soriano P. Roles of PDGF in animal development. Development. 2003;130:4769–4784. doi: 10.1242/dev.00721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. The PDGF alpha receptor is required for neural crest cell development and for normal patterning of the somites. Development. 1997;124:2691–2700. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.14.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding H, Wu X, Bostrom H, Kim I, Wong N, Tsoi B, O’Rourke M, Koh GY, Soriano P, Betsholtz C, Hart TC, Marazita ML, Field LL, Tam PP, Nagy A. A specific requirement for PDGF-C in palate formation and PDGFR-alpha signaling. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1111–1116. doi: 10.1038/ng1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellström M, Kaln M, Lindahl P, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Role of PDGF-B and PDGFR-beta in recruitment of vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes during embryonic blood vessel formation in the mouse. Development. 1999;126:3047–3055. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson A, Siegbahn A, Westermark B, Heldin CH, Claesson-Welsh L. PDGF alpha- and beta-receptors activate unique and common signal transduction pathways. EMBO J. 1992;11:543–550. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05085.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegbahn A, Hammacher A, Westermark B, Heldin CH. Differential effects of the various isoforms of platelet-derived growth factor on chemotaxis of fibroblasts, monocytes, and granulocytes. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:916–920. doi: 10.1172/JCI114519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Abnormal kidney development and hematological disorders in PDGF beta-receptor mutant mice. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1888–1896. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.16.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z, Sasaoka T, Fujimori T, Oya T, Ishii Y, Sabit H, Kawaguchi M, Kurotaki Y, Naito M, Wada T, Ishizawa S, Kobayashi M, Nabeshima Y, Sasahara M. Deletion of the PDGFR-beta gene affects key fibroblast functions important for wound healing. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9375–9389. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413081200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce GF, Mustoe TA, Lingelbach J, Masakowski VR, Griffin GL, Senior RM, Deuel TF. Platelet-derived growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta enhance tissue repair activities by unique mechanisms. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:429–440. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.1.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce GF, Mustoe TA, Senior RM, Reed J, Griffin GL, Thomason A, Deuel TF. In vivo incisional wound healing augmented by platelet-derived growth factor and recombinant c-sis gene homodimeric proteins. J Exp Med. 1988;167:974–987. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.3.974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkumar VS, Sundberg C, Abraham DJ, Rubin K, Black CM. Activation of microvascular pericytes in autoimmune Raynaud’s phenomenon and systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:930–941. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199905)42:5<930::AID-ANR11>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg C, Ivarsson M, Gerdin B, Rubin K. Pericytes as collagen-producing cells in excessive dermal scarring. Lab Invest. 1996;74:452–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby JR, Tappan KA, Seifert RA, Bowen-Pope DF. Chimera analysis reveals that fibroblasts and endothelial cells require platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta expression for participation in reactive connective tissue formation in adults but not during development. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1315–1321. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65384-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bou-Gharios G, Garrett LA, Rossert J, Niederreither K, Eberspaecher H, Smith C, Black C, Crombrugghe B. A potent far-upstream enhancer in the mouse pro alpha 2(I) collagen gene regulates expression of reporter genes in transgenic mice. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:1333–1344. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.5.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Wilkes MC, Leof EB, Hirschberg R. Imatinib mesylate blocks a non-Smad TGF-beta pathway and reduces renal fibrogenesis in vivo. FASEB J. 2005;19:1–11. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2370com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozerdem U, Monosov E, Stallcup WB. NG2 proteoglycan expression by pericytes in pathological microvasculature. Microvasc Res. 2002;63:129–134. doi: 10.1006/mvre.2001.2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivarsson M, Sundberg C, Farrokhnia N, Pertoft H, Rubin K, Gerdin B. Recruitment of type I collagen producing cells from the microvasculature in vitro. Exp Cell Res. 1996;229:336–349. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinnell F, Ho CH, Lin YC, Skuta G. Differences in the regulation of fibroblast contraction of floating versus stressed collagen matrices. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:918–923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver MH, Harrison NK, Bishop JE, Cole PJ, Laurent GJ. A rapid and convenient assay for counting cells cultured in microwell plates: application for assessment of growth factors. J Cell Sci. 1989;92:513–518. doi: 10.1242/jcs.92.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice AB, Ingram JL, Bonner JC. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase regulates growth factor-induced mitogenesis of rat pulmonary myofibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;27:759–765. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0070OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponticos M, Abraham D, Alexakis C, Lu QL, Black C, Partridge T, Bou-Gharios G. Col1a2 enhancer regulates collagen activity during development and in adult tissue repair. Matrix Biol. 2004;22:619–628. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchdunger E, Cioffi CL, Law N, Stover D, Ohno-Jones S, Druker BJ, Lydon NB. Abl protein-tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 inhibits in vitro signal transduction mediated by c-kit and platelet-derived growth factor receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295:139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels CE, Wilkes MC, Edens M, Kottom TJ, Murphy SJ, Limper AH, Leof EB. Imatinib mesylate inhibits the profibrogenic activity of TGF-beta and prevents bleomycin-mediated lung fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1308–1316. doi: 10.1172/JCI19603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft GS, Yang X, Glick AB, Weinstein M, Letterio JL, Mizel DE, Anzano M, Greenwell-Wild T, Wahl SM, Deng C, Roberts AB. Mice lacking Smad3 show accelerated wound healing and an impaired local inflammatory response. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:260–266. doi: 10.1038/12971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Hinz B, Chaponnier C, Brown RA. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:349–363. doi: 10.1038/nrm809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinz B, Mastrangelo D, Iselin CE, Chaponnier C, Gabbiani G. Mechanical tension controls granulation tissue contractile activity and myofibroblast differentiation. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1009–1020. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61776-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler C, Joutsiniemi S, Lindstedt KA, Juutilainen T, Kovanen PT, Eklund KK. Imatinib mesylate inhibits platelet derived growth factor stimulated proliferation of rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;347:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serini G, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Ropraz P, Geinoz A, Borsi L, Zardi L, Gabbiani G. The fibronectin domain ED-A is crucial for myofibroblastic phenotype induction by transforming growth factor-beta1. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:873–881. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.3.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levéen P, Pekny M, Gebre-Medhin S, Swolin B, Larsson E, Betsholtz C. Mice deficient for PDGF B show renal, cardiovascular, and hematological abnormalities. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1875–1887. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.16.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl P, Johansson BR, Leveen P, Betsholtz C. Pericyte loss and microaneurysm formation in PDGF-B-deficient mice. Science. 1997;277:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergers G, Song S, Meyer-Morse N, Bergsland E, Hanahan D. Benefits of targeting both pericytes and endothelial cells in the tumor vasculature with kinase inhibitors. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1287–1295. doi: 10.1172/JCI17929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen RM, Tseng WW, Davis DW, Liu W, Reinmuth N, Vellagas R, Wieczorek AA, Ogura Y, McConkey DJ, Drazan KE, Bucana CD, McMahon G, Ellis LM. Tyrosine kinase inhibition of multiple angiogenic growth factor receptors improves survival in mice bearing colon cancer liver metastases by inhibition of endothelial cell survival mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1464–1468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S, Ewald AJ, Stallcup W, Werb Z, Bergers G. PDGFRbeta(+) perivascular progenitor cells in tumours regulate pericyte differentiation and vascular survival. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:870–879. doi: 10.1038/ncb1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floege J, Eng E, Young BA, Alpers CE, Barrett TB, Bowen-Pope DF, Johnson RJ. Infusion of platelet-derived growth factor or basic fibroblast growth factor induces selective glomerular mesangial cell proliferation and matrix accumulation in rats. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2952–2962. doi: 10.1172/JCI116918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JG, Madtes DK, Raghu G. Effects of platelet-derived growth factor isoforms on human lung fibroblast proliferation and procollagen gene expression. Exp Lung Res. 1993;19:327–344. doi: 10.3109/01902149309064350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahi A, Li M, Ping G, Plathow C, Domhan S, Kiessling F, Lee LB, McMahon G, Grone HJ, Lipson KE, Huber PE. Inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor signaling attenuates pulmonary fibrosis. J Exp Med. 2005;201:925–935. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]