Abstract

Increased autophagic vacuoles (AVs) occur in injured or degenerating neurons, under both developmental and pathological situations. Although regulation of starvation-induced autophagy has been extensively studied, less is known about autophagic responses to pathological damage. The neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) produces mitochondria-targeted injury, which contributes to parkinsonism induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydro-pyridine in mammals. Here, we demonstrate that MPP+ elicited increased autophagy in SH-SY5Y cells, as assessed by electron microscopy, immunofluorescence for the autophagy protein LC3/Atg8, LC3 electrophoretic mobility shift, mitochondrial degradation, and monodansylcadaverine staining for late AVs/autolysosomes. During nutrient deprivation, class III phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K) stimulates autophagy in concert with the autophagy-regulatory protein beclin 1/Atg6. Although PI3K inhibitors and RNA interference knockdown of beclin 1 effectively inhibited autophagy elicited by amino acid deprivation, neither reduced MPP+-induced autophagic stress. In contrast, inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase kinase reduced AV content, mitochondrial degradation, and cell death in MPP+-treated cells. RNA interference studies targeting core Atg proteins also reduced AV content and cell death. Likewise, in primary midbrain dopaminergic neurons, MPP+ elicited increased AV content, which was reversed by inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase kinase but not PI3K. These results implicate a role for extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) signaling upstream of MPP+-elicited autophagic stress. Moreover, pathological stimulation of beclin 1-independent autophagy is associated with neuronal cell death.

Alterations in cellular degradation are implicated in neurodegenerative diseases that include pathological hallmarks of ubiquitinated protein accumulation.1,2 Impaired proteasome function is described in genetic and sporadic Parkinson’s disease.3,4 Likewise, recent studies support a role for autophagy in Parkinson’s disease,5–8 Alzheimer’s disease,9,10 and Huntington’s disease,11–13 although mechanisms that regulate autophagic responses in pathological settings are not well understood.

Autophagy is the regulated process by which cytoplasmic constituents are targeted to lysosomes for degradation.14–16 Macroautophagy involves sequestration of proteins/organelles in double-membrane autophagosomes, followed by maturation to acidic single-membrane autophagosomes that fuse with lysosomes. Direct lysosomal delivery of cytoplasmic proteins can also occur through chaperone-mediated autophagy or lysosomal membrane invagination (microautophagy).17 Hereafter, the term “autophagy” will be used for macroautophagy and “autophagic vacuole” (AV) encompasses all stages of maturation from early autophagosome to secondary lysosome.

Autophagolysosomal alterations such as granulovacuolar degeneration and up-regulation of lysosomal enzymes are observed in Alzheimer’s disease,18,19 and increased nigral AVs are observed in Parkinson/Lewy body disease.8,20 Autophagy is elicited in several neurodegeneration models, contributing to degradation of mutant α-synuclein and huntingtin.6,13,21 Dysregulated autophagy may also contribute to developmental and pathological cell death,22–30 and autophagic processing of prion and β-amyloid precursor proteins has been implicated in dementia.31,32 Thus, a better understanding of autophagy regulation under different stress situations is needed.

Autophagy is classically elicited by nutrient deprivation, and much is known about starvation-induced autophagy. A series of autophagy genes (Atg) have recently been identified.33 Autophagy is initiated by conjugation of Atg12, Atg5, and Atg8/microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3) to the nascent autophagosome membrane. Upstream signals that regulate bulk phase starvation- or trophic deprivation-induced autophagy include Vps34, a class III PI3K, complexed with beclin 1 (Atg6).34,35 Less is known about the signaling regulation of autophagic responses during pathological neuronal injuries.

In this study, 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) was used to elicit mitochondria-targeted injury. MPP+ elicited a robust autophagic response in injured SH-SY5Y cells and primary dopaminergic neurons, which was not diminished by pharmacological and RNA interference treatments that inhibited starvation-induced autophagy. In contrast, inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinases reduced MPP+-elicited AVs, indicating that the upstream regulation of autophagic responses is context dependent. Under physiological conditions, limiting amounts of beclin 1 prevents harmful overactivation of autophagy.36 In this pathological model, stimulation of beclin 1-independent autophagy is associated with neuronal cell death.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Treatments

The SH-SY5Y cell line (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD), a human neuroblastoma cell line that expresses tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and dopamine transporter activities, was maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (BioWhittaker, Walkerville, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 15 mmol/L HEPES, and 2 mmol/L glutamine (BioWhittaker). SH-SY5Y cells were treated with either medium (vehicle control) or MPP+ (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at the LD50 concentration (2.5 mmol/L) for 24 to 48 hours.37,38 Some cultures also received dimethyl sulfoxide vehicle, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) kinase (MEK) inhibitors UO126 (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA) or PD98059 (Sigma), the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase inhibitor SP600125 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), the p38 inhibitor SB202190, 3-methyladenine (3-MA), wortmannin (WT), or LY294002 (Sigma). For amino acid deprivation studies, cells were washed three times and incubated in the presence or absence of amino acids in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C for 1 hour. Cell injury was measured using Alamar Blue (Biosource/Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) or MTS cell viability kits (Promega, Madison, WI), as previously described.39

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Cells grown in 35-mm dishes were fixed for at least 60 minutes in 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4°C. After fixation, cell monolayers were washed three times in PBS and then postfixed in aqueous 1% OsO4 and 1% K3Fe(CN)6 for 1 hour. After 3× PBS washes, the cultures were dehydrated through a graded series of 30 to 100% ethanol, infiltrated, and then embedded in Polybed 812 epoxy resin (Polysciences, Warrington, PA). Ultrathin (60-nm) sections were collected on copper grids and stained with 2% uranyl acetate in 50% methanol for 10 minutes, followed by 1% lead citrate for 7 minutes. Sections were photographed using a JEOL JEM 1210 transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Peabody, MA) at 80 kV.

Fluorescence Microscopy

For LC3 immunofluorescence, SH-SY5Y cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde and stained with rabbit anti-LC3 (1:2000)40 or mouse anti-mitochondrial antigen 60KD (clone 113-1; 1:100; BioGenex, San Ramon, CA), followed by incubation with Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (1:500; Jackson Immuno-Research Laboratories, West Grove, PA) or Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated antibody (1:500; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). After MPP+ or amino acid starvation, cells grown on coverslips were incubated with 0.05 mmol/L monodansylcadaverine (MDC) in Dulbecco’s PBS for 30 minutes at 37°C. The cells were washed three times with Dulbecco’s PBS and mounted on slides. MDC-labeled vacuoles were immediately imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus America Inc., Melville, NY) equipped with triple filter cube [4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, fluorescein isothiocyanate, tetramethylrhodamine B isothiocyanate (TRITC), excitation wavelength/emission filter 350 nm/470 nm; 490 nm/520 nm; 541 nm/572 nm, respectively].

Quantitative Image Analysis

MDC images were processed using MetaMorph image analysis software to quantify the size and number of MDC-positive L-AVs in SH-SY5Y cells. Individual cells or small groups of nonoverlapping cells were manually traced with the software. Discrete MDC-positive structures were identified by autothresholding and digitally scored for pixel area, and the number of MDC-positive structures was divided by the number of nuclei to derive the average number of AVs per cell. Based on the observation that each MDC-positive structure closely approximated a circle, the pixel areas were converted to average diameters using the formula: area = π(d/2),2 where d is diameter, to allow comparison with published diameters of AVs. More than 600 AVs were quantified. In another set of experiments, cells immunostained for mitochondria were analyzed to obtain the pixel area occupied by mitochondria.

Western Blot Analysis and Densitometry

Cell lysates were prepared using lysis buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and a protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail as previously described.41,42 Equal amounts of protein, as determined by Coomassie Plus Protein Assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL), were subjected to electrophoresis through 5 to 15% gradient polyacrylamide gels under reducing conditions, and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The membranes were blocked for 1 hour with 5% nonfat dry milk in 20 mmol/L potassium phosphate, and 150 mmol/L potassium chloride, pH 7.4 containing 0.3% (w/v) Tween 20 and then probed overnight at 4°C with mouse anti-phospho-ERK (1:1000 in phosphate-buffered saline/Tween 20; Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-MAP-LC3 (1:4000),40 mouse anti-p110 mitochondrial protein (1:500; Oncogen, Boston, MA), mouse anti-pyruvate dehydrogenase E2 subunit (1:2000; Molecular Probes), or mouse anti-beclin 1 (1:500; BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Jose, CA), followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated sheep-anti-mouse or rabbit IgG (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). Immunoreaction was detected using an ECL detection kit (Amersham). The membranes were stripped as previously described39,41 and reprobed with anti-β actin as a loading control (Sigma; 1:10,000). Densitometric analysis of blots was performed using the electrophoresis documentation and analysis system 120 (Kodak, Rochester, NY).39,43

RNA Interference

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) for human Atg proteins were synthesized by Ambion (Austin, TX), using previously published targeting sequences (5′-CAGTTTGGACAATCAATA-3′ for beclin 1 and 5′-GGAGUCACAGCUCUUCCUU-3′ for Atg7)26 or by Invitrogen (5′-GCCAGUGGGUUUGGAUCAA-3′ for Atg7, 5′-GGACGAAUUCCAACUUGUU-3′ for Atg5, and 5′-GAAGGCGCUUACAGCUCAA-3′ for LC3). Using fluorescent RNA oligonucleotides (Invitrogen), we found that 2 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 mediates efficient delivery of RNA to SH-SY5Y cells grown in six-well plates, without detectable toxicity. Efficacy and specificity of knockdown was assessed by Western blot, and functional efficacy assessed by LC3 Western blot for all siRNAs except si-LC3, for which MDC fluorescence was used. After optimization experiments, cells were transfected at 50% confluence with 10 nmol/L beclin 1 siRNA, 40 nmol/L LC3 or Atg5 siRNAs, 20 nmol/L Atg7 siRNA, or siControl Nontargeting siRNA Pool (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) 72 hours before amino acid deprivation or treatment with MPP+.

Microplate MDC Assay

After buffer or MPP+ treatment, the cells were incubated with 0.05 mmol/L MDC in PBS at 37°C for 10 minutes, washed with PBS, and collected in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100. Intracellular MDC was measured by fluorescence photometry (excitation wavelength, 335 nm, and emission filter, 525 nm) in a Spectromax M2 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). MDC intensity was normalized to the number of cell nuclei.44

Primary Mouse Midbrain Cultures

The ventral midbrain was dissected from 15-day C57BL/6 mouse embryos (Hilltop Laboratory Animals, Inc., Scottdale, PA), as described previously.45 In brief, cultures were plated in poly-l-lysine-coated 16-well chamber slides (Nunc Laboratory-Tek; Fisher Scientific, Agawam, MA) at a density of 2 × 105 cells/cm2. After 3 days, fresh medium containing 2 μmol/L cytosine arabinoside was applied for 72 hours to inhibit glial proliferation. At 7 days in vitro, MPP+ was administered at the LD50 concentration of 5 μmol/L, a condition that results in selective toxicity to TH immunoreactive neurons.45 Some cultures were simultaneously cotreated with the MEK inhibitor PD98059 (50 μmol/L), 3-MA (5 mmol/L), or WT (50 nmol/L).

Double-Label Immunofluorescence and Data Analysis

Primary cultures from the different treatment conditions were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked using Protein Blocking Solution (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Immunocytochemistry was performed by incubating with mouse anti-TH (1:4000; Calbiochem) and rabbit anti-MAP-LC3 (1:2000)40 at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with Cy3-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:500; Jackson Immuno-Research Laboratories) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:500; Molecular Probes) antibodies. The slides were observed using an Olympus Provis fluorescence microscope (Olympus America Inc.) equipped with the following filter cubes: fluorescein isothiocyanate (excitation 490 nm/emission 520 nm) and TRITC (excitation 541/emission 572 nm). The number of TH neurons was quantified in at least four wells per treatment condition. All TH neurons with a clear nuclear contour and neurites twice the length of the soma were scored as surviving neurons. LC3 immunohistochemistry resulted in two staining patterns: diffuse cytoplasmic staining (basal) and punctate staining (AV-related). The ratio of TH neurons expressing the two LC3 staining patterns was calculated by scoring 100 TH neurons per well.

Statistics

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. Two group comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test. Multiple group comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance and Fisher’s least significant difference. Values of P < 0.05 were defined as statistically significant.

Results

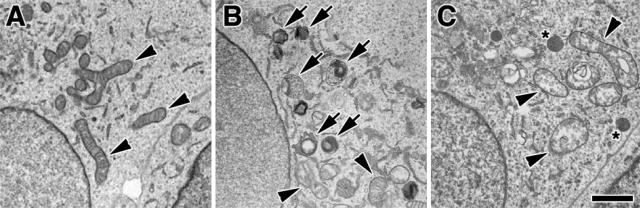

MPP+ Elicits Increased AVs in SH-SY5Y Cells

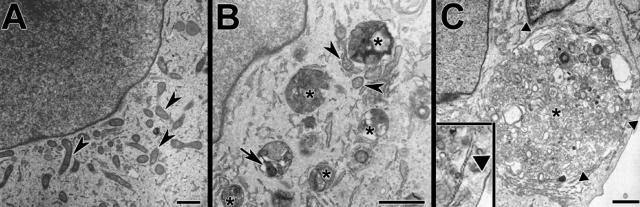

The ultrastructural features of MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells were examined using transmission electron microscopy. Compared with media-treated control cells, in which mitochondria represent the prominent cytoplasmic constituent when viewed at low magnification (Figure 1A), MPP+-treated cells showed few mitochondria. Instead, the toxin-treated cells exhibited abundant AVs at different stages of evolution (Figure 1, B and C). Most AVs were in the same size distribution as starvation-induced mammalian autophagosomes (0.5 to 1.5 μm in diameter)33; however, larger double- and single-membrane AVs were also occasionally observed (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

MPP+ elicits increased AVs in SH-SY5Y cells. In both control (A) and MPP+-treated cells (B and C), the nucleoplasm (top left) remains uncondensed. Mitochondria (arrowheads) are observed at higher density in the control cell. After MPP+ treatment (48 hours), there are numerous AVs (asterisks), some containing recognizable mitochondria (B, arrow). Large AVs were occasionally observed, and at earlier time points, early autophagosomes displayed double membranes (triangles; inset) enclosing disorganized organelles (24 hours; C). Scale bar = 1 μm.

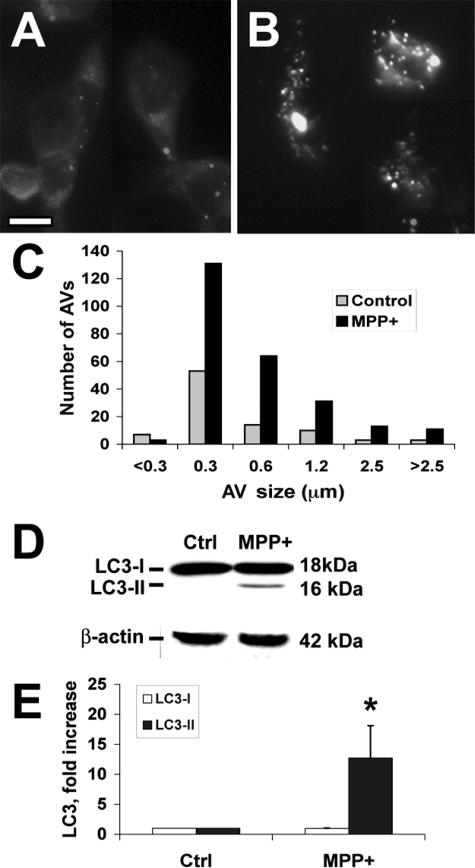

MDC is an autofluorescent dye shown empirically to localize to late AVs/lysosomes (L-AVs) but not endosomes.46 The dye is trapped in acidic, membrane-rich organelles and also exhibits increased fluorescence quantum yield in response to the compacted lipid bilayers present in L-AVs.47 MPP+ treatment increased both the average number of L-AVs per cell and the size distribution of L-AVs (Figure 2, A–C; Table 1). An increase in average L-AV size has also been reported in Purkinje cells subjected to trophic factor and potassium deprivation.27

Figure 2.

MPP+ elicits increased MDC-stained L-AVs and LC3-II recruitment. Control cells treated with media (A) or cells treated with MPP+ (B) for 48 hours were stained with MDC, revealing an increase in the number of L-AVs per cell. C: The size distribution of MDC stained structures was quantified using Metamorph software in 60 cells. D: Western blot analysis for LC3 is shown for a representative experiment. E: Band densitometry performed on four independent experiments reveals significant increases in the autophagosome membrane-associated form of LC3 (LC3-II). *P < 0.01 by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by posthoc multiple comparison testing. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Table 1.

Average Number and Size of L-AVs (±SEM): Effects of MPP+ and UO126

| No. per cell | Average size (μm) | |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 1.31 ± 0.33 | 0.86 ± 0.19 |

| MPP+ | 4.82 ± 1.15 | 3.25 ± 1.12 |

| Control/UO | 1.20 ± 0.44 | 0.77 ± 0.19 |

| MPP+/UO | 0.88 ± 0.25 | 0.92 ± 0.27 |

LC3 (Atg8) conjugation to the nascent AV membrane is required for initiation of autophagy. This is a ubiquitin-like reaction involving conjugation of LC3 to phosphatidylethanolamine.48 The shift from cytoplasmic (LC3-I) to the membrane-bound (LC3-II) form is accompanied by a shift to a faster migrating band detectable by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.49,50 MPP+ treatment elicited significantly increased levels of LC3-II in SH-SY5Y cells (Figure 2, D and E). Increased AVs could also be detected using immunohistochemical staining for LC3. The results derived from MDC staining and LC3 immunohistochemistry were equivalent (for example, see Figure 4 versus Figure 5).

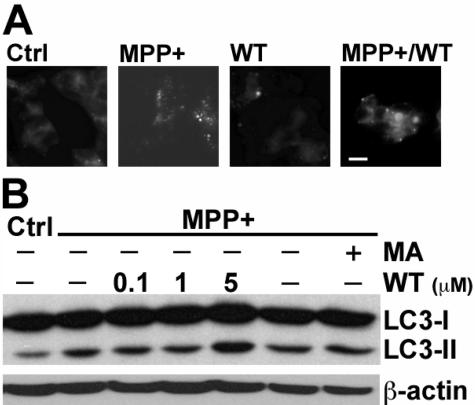

Figure 4.

Inhibitors of PI3K did not decrease MPP+-elicited AVs in SH-SY5Y cells. A: SH-SY5Y cells were treated with MPP+, WT (10 μmol/L), or a combination of MPP+ and wortmannin for 48 hours and then stained with MDC. Note that wortmannin did not block the MPP+-induced increase in granular MDC staining. B: Cells were treated with MPP+ in the presence or absence of the indicated doses of WT and in the presence or absence of 3-MA (MA, 5 mmol/L). Western blot analysis for LC3 shows that neither inhibitor blocked the MPP+-elicited increase in LC3-II. Scale bar = 10 μm.

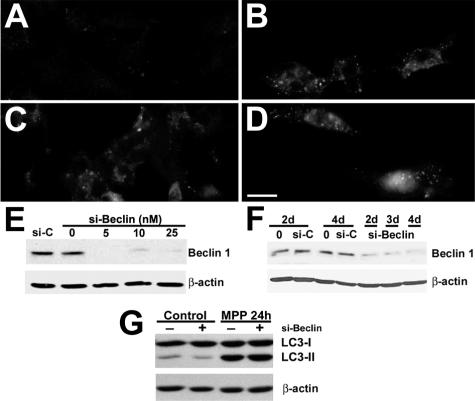

Figure 5.

RNA interference knockdown of beclin 1 expression did not decrease MPP+-elicited AVs. Untreated control SH-SY5Y cells (A), MPP+-treated cells (B), cells treated with control siRNA (10 nmol/L) 72 hours before MPP+ (C), and cells treated with siRNA directed against human beclin 1 (10 nmol/L) for 72 hours before MPP+ treatment (D) were immunostained for LC3 after 24 hours of MPP+. Neither control siRNA nor beclin 1 siRNA reduced MPP+-induced granular LC3 redistribution. E: Western blot analysis demonstrates reduction of beclin 1 expression at 72 hours after siRNA treatment compared with both control siRNA-treated cells (si-C) and transfection controls lacking siRNA (0). F: Similar levels of reduction were observed 48 to 96 hours after treatment with 10 nmol/L si-Beclin. G: LC3 Western blot analysis shows that beclin 1 siRNA did not reduce MPP+-induced LC3-II levels. Scale bar = 10 μm.

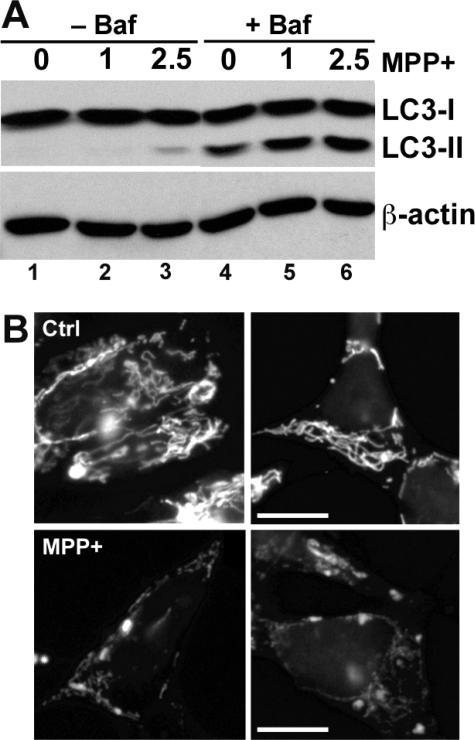

Increased AV Content in MPP+-Treated Cells Reflects Autophagy Induction

Because a portion of LC3-II remains in L-AVs until degraded, both AV formation and impaired AV degradation can contribute to increased AVs and LC3-II. A method to assess AV induction is to measure LC3-II levels in the presence of an inhibitor of AV fusion/degradation.51 MPP+ caused increased LC3-II compared with control cells in the presence of bafilomycin A1, an inhibitor of early AV acidification and fusion to lysosomes at doses ≥10 nmol/L52,53 (Figure 3A, compare lanes 5 and 6 with lane 4). The fact that bafilomycin A1 markedly increased LC3-II levels in MPP+-treated cells, compared with MPP+ treatment alone, also implies that degradation is intact after 24 hours of MPP+ treatment (Figure 3A, compare lanes 2 versus 5 and 3 versus 6).

Figure 3.

MPP+ induces autophagy and mitochondrial loss. A: SH-SY5Y cells were treated with two doses of MPP+ (mmol/L) in the presence or absence of bafilomycin A1 (10 nmol/L) to inhibit AV fusion to lysosomes and subsequent degradation. After 24 hours, cell lysates were analyzed for LC3 by Western blot, and the blots were stripped and reprobed for β-actin as a loading control. At this time point, there is ∼20% cell death at the 2.5-mmol/L dose and no cell death at the 1-mmol/L dose of MPP+. Bafilomycin increased LC3-II content in all treatment conditions, indicating intact degradation in the absence of bafilomycin. Moreover, cells treated with MPP+ in the presence of bafilomycin had more LC3-II than cells treated with media vehicle in the presence of bafilomycin, indicating induction of autophagy by MPP+. B: SH-SY5Y cells treated for 24 hours with 2.5 mmol/L MPP+ (bottom) show decreased immunostaining for the 60-kD mitochondrial complex IV protein80 compared with control media-treated cells (top). See also Figure 7E for quantitative image analysis and Figure 7D for Western blot analysis of mitochondrial matrix and membrane proteins. Scale bar = 10 μm.

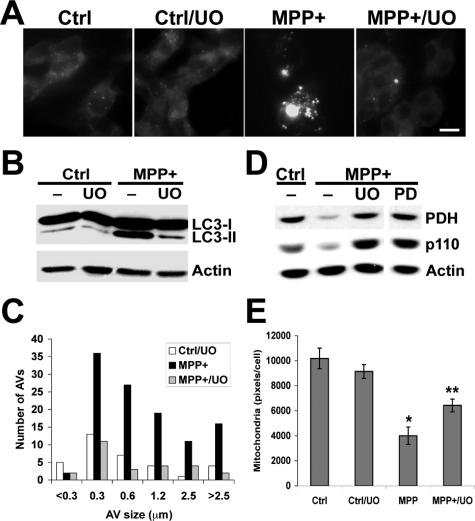

Autophagy is the primary mechanism for organelle degradation. Because the electron micrographs suggest disappearance of mitochondria from MPP+-treated cells (Figure 1), we measured mitochondrial content in control and MPP+-treated cells using immunofluorescence and Western blot analysis. These studies show fragmentation of mitochondria and reduction in mitochondrial pixel area in MPP+-treated cells (Figure 3B; see also Figure 7E for quantitative image analysis). MPP+ treatment also reduced the levels of the mitochondrial matrix protein pyruvate dehydrogenase and a mitochondrial membrane protein p11054 relative to β-actin and total protein (Figure 7D). Taken together with the bafilomycin data, these experiments indicate that MPP+ induces autophagic mitochondrial degradation.

Figure 7.

Effects of MEK inhibitors on MPP+-elicited autophagic responses. A: SH-SY5Y cells treated with MPP+ and/or UO126 were stained with MDC, revealing inhibition of the MPP+-induced increase in MDC-stained L-AVs by UO126. B: Cells treated with MPP+ in the presence or absence of the MEK inhibitor UO126 (UO; 10 μmol/L) were analyzed by LC3 Western blot, showing that UO126 effectively reduced the levels of MPP+-elicited LC3-II. Similar results were observed using the MEK inhibitor PD98059 (20 μmol/L; not illustrated). C: The size distribution of MDC stained L-AVs in 24 consecutive cells for each condition was quantified using Metamorph software. D: The effects of the MEK inhibitors UO126 and PD98059 on MPP+-induced loss of mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase and the p110 mitochondrial membrane protein were analyzed at 48 hours by Western blot. Equal amounts of total protein were loaded per lane, and the blot was reprobed for β-actin as a loading control. E: The effects of the MEK inhibitor UO126 on mitochondrial immunoreactivity in control and MPP+-treated cells were analyzed in 292 cells stained as in Figure 3B, using Metamorph software. *P < 0.05 versus control; **P < 0.05 versus MPP+ alone, ANOVA/Fisher’s LSD. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Classic Inhibitors of Amino Acid Deprivation-Associated Autophagy Do Not Inhibit the Autophagic Response Elicited by MPP+ Treatment

Pharmacological inhibitors of PI3Ks, including WT and 3-MA, are effective at inhibiting starvation-induced autophagy.55,56 However, neither 3-MA nor WT was able to inhibit the increase in AVs/L-AVs induced by MPP+ treatment (Figure 4). Although higher doses of these inhibitors can elicit apoptotic death, the doses used for 3-MA (5 mmol/L) and WT (50 nmol/L to 5 μmol/L) had no significant effect on basal SH-SY5Y viability.

In intestinal cells, it has been shown that class I and class III PI3Ks have differential effects on autophagy.57 Because lower doses of WT may be more selective at inhibiting autophagy, we tried a range of WT doses. None of these treatments was effective at reducing MPP+-elicited AVs/L-AVs (Figure 4B). For subsequent studies, 50- to 100-nmol/L doses were used.

Knockdown of Beclin 1 Expression Using RNA Interference Failed to Inhibit MPP+-Induced Autophagy

Beclin 1 associates with the class III PI3K to induce autophagy.34 As an alternative method to address the role of the class III PI3K pathway in regulating autophagic responses elicited during MPP+ injury, we used double-stranded siRNA for human beclin 126 to further investigate the potential role of this pathway in MPP+-elicited AVs. Beclin 1 siRNA reduced basal levels of LC3-II (Figure 5G, left); however, neither the negative control siRNA (Figure 5C) nor the human beclin 1 siRNA (Figure 5D) was able to attenuate the autophagic response elicited by MPP+, as assessed by LC3 immunofluorescence (Figure 5B), MDC staining (not illustrated), or LC3 gel shift (Figure 5G, right). Beclin 1 Western blots indicated effective knockdown of beclin 1 protein expression before and during MPP+ treatment, which was added 72 hours after siRNA transfection (Figure 5, E and F).

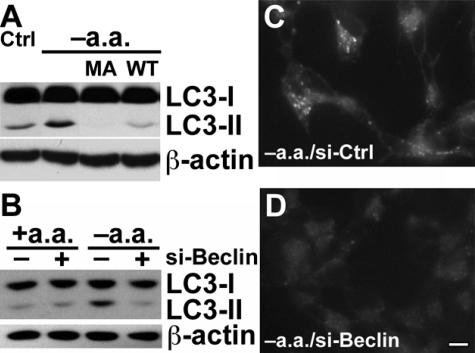

Regulatory Pathways for Amino Acid Deprivation Are Intact in SH-SY5Y Cells

Control experiments were performed to verify that the beclin 1/PI3K signaling pathway reported for starvation-induced autophagy is intact in SH-SY5Y cells. Deprivation of amino acids resulted in increased autophagy that was inhibited by 3-MA and WT (Figure 6A). Likewise, RNA interference studies demonstrated that the starvation-induced response required beclin 1 expression (Figure 6, B and D), whereas control siRNAs had no effect (Figure 6C). Thus, the differences in regulation of AV-associated responses probably reflect differences in the initiating stimuli.

Figure 6.

Starvation-induced autophagy is sensitive to PI3K inhibition and beclin 1 siRNA in SH-SY5Y cells. A: SH-SY5Y cells were washed and incubated in the presence or absence of amino acids for 1 hour and analyzed by LC3 Western blot. The ability of 3-MA (MA; 5 mmol/L) or of WT (0.1 μmol/L) to inhibit the LC3-II shift was evaluated. B: SH-SY5Y cells were treated with control siRNA or beclin 1 siRNA (10 nmol/L) for 3 days before being switched to either amino acid-containing or amino acid-deprived media for 1 hour and subjected to LC3 Western blot analysis. C and D: Amino acid-deprived SH-SY5Y cells that had previously been treated with either control siRNA (C) or beclin 1 siRNA (D) were stained with MDC. Scale bar = 10 μm.

The ERK Signaling Pathway Acts Upstream of Autophagy in SH-SY5Y Cells

In some cell types, autophagy is regulated by the ERK signaling pathway.58 Inhibitors of the upstream ERK kinase MEK effectively suppressed the autophagic response to MPP+ injury as assessed by MDC staining (Figure 7A), LC3 gel shift (Figure 7B), or LC3 immunofluorescence (not illustrated). In addition to reducing the average number of L-AVs per cell, MEK inhibition also reversed the MPP+-elicited change in the size distribution of L-AVs (Figure 7C; Table 1). Moreover, MEK inhibitors effectively blocked the MPP+-induced decrease in mitochondrial matrix and membrane proteins (Figure 7D) and significantly reduced the MPP+-elicited disappearance of mitochondrial immunofluorescence (Figure 7E).

The effect of MEK inhibitors on the MPP+-elicited AV response was also studied ultrastructurally. EM studies confirm a decrease in AV-like structures in cells cotreated with MPP+ and UO126 (Figure 8C) compared with those treated with MPP+ alone (Figure 8B). Moreover, swollen mitochondria were prominent in cells cotreated with MPP+ and UO126, suggesting that the effects of UO126 occurred downstream of the initial phase(s) of mitochondrial injury.

Figure 8.

UO126 reduces EM evidence of AVs in MPP+-treated cells. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with buffer (A), MPP+ (B), or MPP+ in the presence of the MEK inhibitor UO126 (C) for 24 hours. Mitochondria (arrowheads) are readily identified in both control (A) and MPP+/UO126-treated (C) cells, but AVs (arrows) are most prominent in cells treated with MPP+ alone (B). Although AVs in MPP+-treated cells displayed multiple membrane layers and/or heterogeneous contents (B, arrows), cells cotreated with MPP+ and UO126 contained occasional round, uniformly dense structures (C, asterisks) the significance of which is unclear but could represent highly condensed AVs or early lysosomes. C: Cotreatment with UO126 reduced AV-like structures but did not prevent MPP+-induced mitochondrial swelling. Scale bar = 1 μm.

Reagents That Reduce MPP+-Induced AVs also Conferred Protection from Cell Death

MEK inhibitors conferred significant protection from MPP+ toxicity (Figure 9A; Table 2).59 In contrast, neither pharmacological (3-MA and WT) nor siRNA inhibition of the beclin 1 pathway showed significant effects on cell death in SH-SY5Y cells (Table 2). Low doses of the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) inhibitor SP600125 (Table 2) were partially effective in reducing MPP+-induced cell death, LC3-II levels, and degradation of mitochondrial proteins, whereas a p38 inhibitor had no effect on MPP+ toxicity (not illustrated).

Figure 9.

MAP kinase inhibitors and Atg protein knockdown confer protection from MPP+ toxicity. A: Viability of vehicle control and MPP+-treated cells that were cotreated with different concentrations of the MEK inhibitor UO126 was assessed at 48 hours using the MTS assay. *P < 0.05 by ANOVA/Fisher’s LSD. B: SH-SY5Y cells were treated with MPP+ for increasing amounts of time before harvest for phospho-ERK and LC3 Western blot analysis. Blots were stripped and reprobed for β-actin as a loading control. C: SH-SY5Y cells were treated with MPP+ alone (M) or with UO126 (10 μmol/L) added at different intervals relative to MPP+ treatment. Data are expressed as percentage of buffer-treated control cells that did not receive MPP+ (C). *P < 0.05 versus MPP+ alone by ANOVA/Fisher’s LSD. D: Viability of si-Ctrl and LC3 siRNA-treated cells after 48 hours of MPP+ treatment. *P < 0.05 versus MPP+ alone, Student’s t-test. Inset: Cells treated with control siRNA or si-LC3 for 3 days before MPP+ treatment × 1 day were analyzed by Western blot for LC3 expression levels. Note reduction in both LC3-I levels and inhibition of MPP+-induced LC3-II shift in si-LC3-treated cells. E: Cells treated with control or LC3-directed siRNA for 3 days were treated with buffer or MPP+ for an additional 24 hours before fluorescent microplate analysis of intracellular MDC.44 The presence of si-LC3 reduced both basal and MPP+-induced MDC fluorescence. F: Viability of cells treated with control siRNA and siRNAs directed at Atg7 or Atg5 before MPP+ treatment × 48 h. *P < 0.05 versus MPP+ alone, ANOVA/Fisher’s LSD. Insets: Atg7 and Atg5 expression was monitored by Western blot relative to β-actin.

Table 2.

Effects of Signaling Inhibitors or siRNA Knockdown on MPP+ Toxicity

| Pathway | Inhibitor | % Protection versus MPP+ alone | SEM | n | AV response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEK/ERK | UO | 50.7* | 6.7 | 5 | Decrease |

| MEK/ERK | PD | 33.9* | 3.0 | 3 | Decrease |

| JNK | SP | 31.3* | 6.9 | 4 | Decrease |

| PI3K/beclin | MA | −11.5 | 14.0 | 4 | No change |

| PI3K/beclin | WT | 1.5 | 9.0 | 4 | No change |

| PI3K/beclin | si-Beclin | 3.0 | 13.4 | 2 | No change |

| Core machinery | si-LC3 | 29.0* | 3.7 | 3 | Decrease |

| Control siRNA | si-CTRL | 3.5 | 6.4 | 4 | No change |

Positive numbers indicate protection; negative numbers indicate exacerbation of MPP+ toxicity. Average ± SEM from n independent experiments. UO, UO126, 10 μmol/L (protection observed at 1 to 10 μmol/L); PD, PD98059, 20 μmol/L (protection observed at 1 to 100 μmol/L); SP, SP600125 (protection observed at 1 to 2 μmol/L, but not at 10 μmol/L or higher); MA, 3-methyladenine, 5 mmol/L (no protection observed at 1 to 10 mmol/L); WT, 50 nmol/L (no protection observed at 1 nmol/L to 10 μmol/L). LY294002 (20 μmol/L) and SB202190 (5 to 10 μmol/L) showed no effects on cell survival (not shown).

P < 0.05 versus si-Ctrl/vehicle by ANOVA/Fisher’s.

ERK Phosphorylation Precedes Increased LC3 Shift, and MEK Inhibitors Confer Protection If Added before LC3-II Accumulation

Time course experiments were performed to characterize further the relationship between ERK activation and the AV response in MPP+-treated cells. Increased phospho-ERK was observed beginning ∼8 hours after MPP+ administration, and increased LC3-II shift was observed by 16 hours (Figure 9B). Moreover, delayed protection assays revealed that UO126 added up to ∼12 hours after initiation of MPP+ injury conferred the same degree of protection as observed when UO126 was present at the beginning of the experiment (Figure 9C). However, if the UO126 was added >20 hours after MPP+ treatment, cell viability was not significantly different from cells treated with MPP+ alone. These results implicate AV responses downstream of the ERK pathway.

Reduced Expression of Core Atg Proteins Results in Reduced MPP+ Toxicity

To investigate the potential role of AV responses in MPP+ toxicity, we performed siRNA experiments to knockdown expression of LC3. Cells treated with siRNA for LC3 showed significant protection from MPP+ toxicity (Figure 9D), accompanied by ∼50% reduction in the levels of LC3-I, inhibition of the MPP+-induced LC3-II shift, and a 40% reduction in MPP+-induced increases in MDC fluorescence after correcting for siRNA-related suppression of basal MDC fluorescence (Figure 9E). Moreover, siRNA knockdown of Atg5 and Atg7, two other proteins involved in membrane conjugation necessary for initiating autophagy, also showed significant protection (Figure 9F), although to a lesser degree than that seen with UO126. The reduction in cell death was not due to reduction in MPP+-elicited caspase 3 activity nor were there inhibitory effects of the Atg siRNAs on ERK expression or proteasome activity (not illustrated).

MPP+ Elicits Increased AV Content in Primary Dopaminergic Neurons That Is Resistant to PI3K Inhibitors but Sensitive to MEK Inhibition

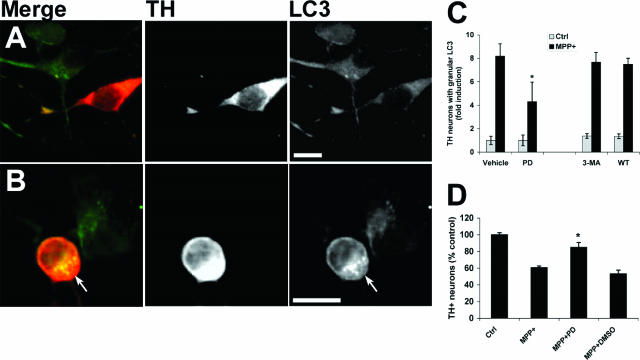

Primary mouse midbrain cultures were treated with MPP+ as previously described using a dose that caused selective injury to TH immunoreactive dopaminergic neurons.45 Double-label immunofluorescence for TH and LC3 showed that MPP+ elicited the appearance of granular LC3 staining in TH neurons (Figure 10B, arrow), indicative of autophagy,50,60 whereas noninjured, non-TH neurons retained a light, diffuse staining pattern similar to control cultures (Figure 10A). MEK inhibition resulted in significant reduction in TH immunoreactive cells displaying LC3-labeled AVs, compared with MPP+ treatment alone (Figure 10C). In contrast, neither 3-MA nor WT decreased the MPP+-elicited autophagic response. As observed in SH-SY5Y cells, MEK inhibition conferred protection from MPP+ in primary midbrain TH neurons (Figure 10D).

Figure 10.

MPP+ elicits increased AV content in primary dopaminergic neurons that is blocked by MEK inhibition but not by inhibitors of PI3K. Primary mouse midbrain cultures were treated with media (A) or 5 μmol/L MPP+ (B) for 24 hours. Cultures were double immunolabeled for LC3 (green channel) and TH (red channel). In control cultures, LC3 immunofluorescence produces a diffuse cytoplasmic pattern in both TH+ and non-TH neurons (A). MPP+ treatment causes development of granular LC3 immunofluorescence in the TH+ neuron (B, arrow). C: Primary midbrain cultures were treated with MPP+ in the presence or absence of the MEK inhibitor PD98059 (PD), 3-MA, or WT for 24 hours before fixation and LC3 immunocytochemistry. The percentage of TH+ neurons showing granular LC3 staining was determined and normalized to Ctrl/Vehicle cultures. Results show the mean (±SEM) from three independent cultures. *P < 0.05 for MPP+/PD versus MPP+/Vehicle by ANOVA/Fisher’s LSD. D: Primary midbrain cultures were treated with MPP+ for 48 hours in the presence or absence of PD98059, and the numbers of TH neurons were determined as described in Materials and Methods. *P < 0.05 versus MPP+ alone. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Discussion

Although autophagy has been most intensively studied in response to limiting nutrient or trophic factor status, a growing body of literature implicates autophagy-related processes in neurological injury and disease mechanisms. Under these circumstances, the AV response may be triggered by damage to proteins or organelles. We found that a robust AV response is elicited in the MPP+ model of mitochondria-targeted neuronal injury. In both SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells and in primary mouse dopaminergic midbrain neurons, the MPP+-induced AV response was resistant to inhibitors of a major starvation-induced autophagy signaling pathway involving beclin 1 and PI3K. In contrast, MEK inhibition reversed the AV increase and mitochondrial loss elicited by MPP+ (Figures 7, 8, and 10), implicating ERK/MAPK signaling in regulating MPP+-elicited autophagy. Moreover, Atg protein siRNA data indicate that pathological stimulation of beclin 1-independent autophagy is associated with neuronal cell death.

One potential explanation for differences in the effects of PI3K inhibitors on starvation- versus injury-induced autophagy may relate to the relative balance of class I versus class III PI3K activities within a given cell type or in a given context. In intestinal carcinoma cells, class I and class III PI3K have opposing effects on autophagy—the class III pathway promotes autophagy, whereas the class I pathway inhibits autophagy.57 In situations where the class I PI3Ks are not activated, the inhibitory effects of PI3K inhibitors on autophagy predominate. However, under injury situations involving high class I PI3K activity, effects of inhibiting both pathways may cancel each other out in terms of autophagy induction. Although 3-MA was originally described as a specific inhibitor of autophagy,56 it also inhibits the class I PI3K pathway (J.-H. Zhu and C.T. Chu, unpublished observation). In HT-29 carcinoma cells, 50 nmol/L WT is more effective at inhibiting autophagy than micromolar doses, perhaps reflecting the contribution of conflicting pathways (P. Codogno, INSERM, Châtenay-Malabry, France, personal communication). In this context, it is interesting to note that the highest WT dose resulted in a slight increase in LC3-II levels (Figure 4B).

The beclin 1 siRNA studies, however, suggest that mechanisms other than simply concurrent inhibition of opposing pathways may also account for the difference in regulation of starvation- and injury-induced autophagy. Direct association between beclin 1 and class III PI3K is essential for the autophagy-promoting effects of this pathway.34 Haploinsufficiency of beclin 1 expression levels is sufficient to inhibit autophagy in vivo and in vitro.61,62 As expected, beclin 1 siRNA effectively reduced starvation-induced autophagy (Figure 6). However, despite effective knockdown of beclin 1 protein expression throughout the duration of MPP+ treatment, MPP+-elicited AVs/L-AVs were unaffected by beclin 1 siRNA treatment, as assessed by MDC staining, LC3 immunofluorescence, and LC3-II gel shift. Together with the wortmannin studies, these results implicate the existence of class III PI3K/beclin 1-independent mechanisms of autophagy.

Although starvation- and trophic factor deprivation-associated autophagy mediates nonselective bulk degradation of cytoplasmic constituents, the possibility of organelle-targeted autophagy has been less studied. In yeast, pexophagy, or selective degradation of peroxisomes is orchestrated by both a common set of autophagy genes and exquisitely specific regulatory mechanisms that prevent destruction of the last peroxisome.63,64 The yeast Atg 1 kinase has been implicated in selective and nonselective autophagy in yeast, but its substrates are still unknown, and kinases that serve similar roles have not yet been established in mammalian systems.65 In pathological states, apparently selective destruction of the entire mitochondrial complement occurs after several apoptotic stimuli.66 Although this was observed in the context of experimentally arrested apoptosis, mechanisms that target organelles for degradation may differ under physiological and pathological situations. In this regard, it is interesting to note that 3-MA/WT-resistant autophagy has also been observed in another model of organelle-targeted injury (María Isabel Colombo, Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, Mendoza, Argentina, personal communication).

The involvement of the ERK pathway in stimulating MPP+-induced AV responses is interesting, because ERK has been reported to localize to mitochondria (reviewed in Ref. 67), and activated ERK is observed ultrastructurally in abnormal mitochondria and AVs within degenerating substantia nigra neurons.8 This granular, cytoplasmic pattern of phospho-ERK accumulation is observed not only in Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia patient brains (reviewed in Ref. 68) but also in asymptomatic individuals showing postmortem pathological evidence of early synucleinopathy.69 ERK is also involved in promoting autophagy elicited by amino acid deprivation and by soyasaponins in intestinal carcinoma cells,58,70 and the JNK subfamily of MAPKs has been implicated in cell death-associated autophagy.7 Taken together, the data implicate a potential role for MAPKs in regulating autophagic responses and mitochondrial degradation during neuronal cell death.

Although autophagy plays beneficial roles in homeostatic maintenance and clearance of aggregate-prone proteins, including those observed in neurodegenerative diseases,6,12,71 a growing number of studies also implicate autophagy-related processes in mechanisms of cell death.23,26,27,29,72–76 The data summarized in Table 2 demonstrate a close relationship between changes in AV content and subsequent cell death. Moreover, time course, ultrastructural, and siRNA studies directed at the core Atg machinery all suggest that the protective effects of MEK/ERK pathway inhibitors are mediated at least in part by changes in the mitochondrial autophagic response, rather than by preventing the initiating injury. The magnitude of protection conferred by siRNA studies was less than that conferred by UO126, however, suggesting that MEK inhibitors may also play additional roles. This is not surprising because multiple adaptive and death-promoting pathways are activated under pathological situations. On the other hand, it is possible that autophagy was only inhibited in a subset of cells and that stable short hairpin siRNA cell lines are needed to optimize knockdown further. Nevertheless, the data suggest that autophagy contributes to MEK/ERK-dependent toxicity in MPP+-treated cells.

It has been proposed that the degree of autophagy elicited may play a role in cell fate decisions, with low levels serving a homeostatic role and high levels promoting cell death, either directly or indirectly. Beclin 1 was originally identified as a Bcl-2-interacting protein, and competition for limiting amounts of beclin 1 has been shown to prevent harmful overactivation of autophagy.36 It is interesting to note that autophagic responses induced in several pathological contexts including MPP+ toxicity (Figures 4, 5, and 10; Table 2) and viral replication77 are resistant to inhibitors of this pathway. Thus, either the beclin 1/PI3K pathway is not involved in regulating autophagy in these pathological situations, or alternative mechanisms exist that can complement or bypass this pathway. Furthermore, beclin 1 independence implies the possibility of escape from regulatory feedback mechanisms, contributing to stress/injury when excessive autophagic demand cannot be balanced by cellular reserves.75

To summarize, increased autophagic stress75 is observed in aging and many disease states, most likely in response to protein or organelle damage.78,79 Although this may initially represent a compensatory response, recent studies also suggest that autophagy can play a pathogenic role, particularly when overstimulated.14,15,66 Whichever the case, the current data indicate that regulation of autophagy elicited by MPP+ injury differs from that of starvation-induced autophagy. Differences in upstream regulation of autophagic responses in situations of organelle damage versus general deprivation stress, inefficient completion of degradative recycling, and/or loss of feedback mechanisms to prevent excessive activation of degradative systems may underlie divergent effects of autophagy in different contexts.

Acknowledgments

We thank Noboru Mizushima (Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science, Tokyo, Japan) for the Atg5 antibody and helpful discussion, William Dunn (University of Florida, Gainesville, FL) for the Atg7/HsGSA7 antibody, and Xiao-Ming Yin (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) for Atg 5 and Atg 8 siRNA sequences. We thank David Sulzer (Columbia University, New York), Patrice Codogno (INSERM), and María Isabel Colombo (Universidad Nacional de Cuyo) for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Charleen T. Chu, M.D., Ph.D., Division of Neuropathology, Room A-516 UPMC Presbyterian, 200 Lothrop St., Pittsburgh, PA 15213. E-mail: ctc4@pitt.edu or chuct@post.harvard.edu.

Related Commentary on page 16

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant NS40817), by a pilot grant from the University of Pittsburgh Center for the Environmental Basis of Human Disease, and in part by the Pathology Postdoctoral Research Training Program at the University of Pittsburgh.

References

- Ross CA, Poirier MA. Protein aggregation and neurodegenerative disease. Nat Med. 2004;10(Suppl):S10–S17. doi: 10.1038/nm1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CT, Caruso JL, Cummings TJ, Ervin J, Rosenberg C, Hulette CM. Ubiquitin immunochemistry as a diagnostic aid for community pathologists evaluating patients who have dementia. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:420–426. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaught KS, Olanow CW, Halliwell B, Isacson O, Jenner P. Failure of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in Parkinson’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:589–594. doi: 10.1038/35086067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada H, Kohno R, Kihara T, Izumi Y, Sakka N, Ibi M, Nakanishi M, Nakamizo T, Yamakawa K, Shibasaki H, Yamamoto N, Akaike A, Inden M, Kitamura Y, Taniguchi T, Shimohama S. Proteasome mediates dopaminergic neuronal degeneration, and its inhibition causes alpha-synuclein inclusions. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10710–10719. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen KE, Fon EA, Hastings TG, Edwards RH, Sulzer D. Methamphetamine-induced degeneration of dopaminergic neurons involves autophagy and upregulation of dopamine synthesis. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8951–8960. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-08951.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo AM, Stefanis L, Fredenburg R, Lansbury PT, Sulzer D. Impaired degradation of mutant alpha-synuclein by chaperone-mediated autophagy. Science. 2004;305:1292–1295. doi: 10.1126/science.1101738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Santos C, Ferrer I, Santidrian AF, Barrachina M, Gil J, Ambrosio S. Dopamine induces autophagic cell death and alpha-synuclein increase in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. J Neurosci Res. 2003;73:341–350. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J-H, Guo F, Shelburne J, Watkins S, Chu CT. Localization of phosphorylated ERK/MAP kinases to mitochondria and autophagosomes in Lewy body diseases. Brain Pathol. 2003;13:473–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2003.tb00478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon RA, Wegiel J, Kumar A, Yu WH, Peterhoff C, Cataldo A, Cuervo AM. Extensive involvement of autophagy in Alzheimer disease: an immuno-electron microscopy study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:113–122. doi: 10.1093/jnen/64.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu WH, Cuervo AM, Kumar A, Peterhoff CM, Schmidt SD, Lee JH, Mohan PS, Mercken M, Farmery MR, Tjernberg LO, Jiang Y, Duff K, Uchiyama Y, Naslund J, Mathews PM, Cataldo AM, Nixon RA. Macroautophagy: a novel beta-amyloid peptide-generating pathway activated in Alzheimer’s disease. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:87–98. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin ZH, Wang Y, Kegel KB, Kazantsev A, Apostol BL, Thompson LM, Yoder J, Aronin N, DiFiglia M. Autophagy regulates the processing of amino terminal huntingtin fragments. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:3231–3244. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersén A, Larsen KE, Behr GG, Romero N, Przedborski S, Brundin P, Sulzer D. Expanded CAG repeats in exon 1 of the Huntington’s disease gene stimulate dopamine-mediated striatal neuron autophagy and degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1243–1254. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.12.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B, Vacher C, Berger Z, Davies JE, Luo S, Oroz LG, Scaravilli F, Easton DF, Duden R, O’Kane CJ, Rubinsztein DC. Inhibition of mTOR induces autophagy and reduces toxicity of polyglutamine expansions in fly and mouse models of Huntington disease. Nat Genet. 2004;36:585–595. doi: 10.1038/ng1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell. 2004;6:463–477. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum JJ, DeBerardinis RJ, Thompson CB. Autophagy in metazoans: cell survival in the land of plenty. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:439–448. doi: 10.1038/nrm1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergamini E, Cavallini G, Donati A, Gori Z. The role of macroautophagy in the ageing process, anti-ageing intervention and age-associated diseases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2392–2404. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo AM. Autophagy: many paths to the same end. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;263:55–72. doi: 10.1023/B:MCBI.0000041848.57020.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadelmann C, Deckwerth TL, Srinivasan A, Bancher C, Bruck W, Jellinger K, Lassmann H. Activation of caspase-3 in single neurons and autophagic granules of granulovacuolar degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for apoptotic cell death. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1459–1466. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65460-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo AM, Barnett JL, Berman SA, Li J, Quarless S, Bursztajn S, Lippa C, Nixon RA. Gene expression and cellular content of cathepsin D in Alzheimer’s disease brain: evidence for early up-regulation of the endosomal-lysosomal system. Neuron. 1995;14:671–680. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglade P, Vyas S, Javoy-Agid F, Herrero MT, Michel PP, Marquez J, Mouatt-Prigent A, Ruberg M, Hirsch EC, Agid Y. Apoptosis and autophagy in nigral neurons of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Histol Histopathol. 1997;12:25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornai F, Lenzi P, Gesi M, Soldani P, Ferrucci M, Lazzeri G, Capobianco L, Battaglia G, De Blasi A, Nicoletti F, Paparelli A. Methamphetamine produces neuronal inclusions in the nigrostriatal system and in PC12 cells. J Neurochem. 2004;88:114–123. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inbal B, Bialik S, Sabanay I, Shani G, Kimchi A. DAP kinase and DRP-1 mediate membrane blebbing and the formation of autophagic vesicles during programmed cell death. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:455–468. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue L, Fletcher GC, Tolkovsky AM. Autophagy is activated by apoptotic signalling in sympathetic neurons: an alternative mechanism of death execution. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999;14:180–198. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockshin RA, Zakeri Z. Apoptosis, autophagy, and more. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2405–2419. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama Y. Autophagic cell death and its execution by lysosomal cathepsins. Arch Histol Cytol. 2001;64:233–246. doi: 10.1679/aohc.64.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Alva A, Su H, Dutt P, Freundt E, Welsh S, Baehrecke EH, Lenardo MJ. Regulation of an ATG7-beclin 1 program of autophagic cell death by caspase-8. Science. 2004;304:1500–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.1096645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florez-McClure ML, Linseman DA, Chu CT, Barker PA, Bouchard RJ, Le SS, Laessig TA, Heidenreich KA. The p75 neurotrophin receptor can induce autophagy and death of cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4498–4509. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5744-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baehrecke EH. Autophagic programmed cell death in Drosophila. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:940–945. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu S, Kanaseki T, Mizushima N, Mizuta T, Arakawa-Kobayashi S, Thompson CB, Tsujimoto Y. Role of Bcl-2 family proteins in a non-apoptotic programmed cell death dependent on autophagy genes. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1221–1228. doi: 10.1038/ncb1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyo JO, Jang MH, Kwon YK, Lee HJ, Jun JI, Woo HN, Cho DH, Choi B, Lee H, Kim JH, Mizushima N, Oshumi Y, Jung YK. Essential roles of Atg5 and FADD in autophagic cell death: dissection of autophagic cell death into vacuole formation and cell death. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20722–20729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413934200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doh-Ura K, Iwaki T, Caughey B. Lysosomotropic agents and cysteine protease inhibitors inhibit scrapie-associated prion protein accumulation. J Virol. 2000;74:4894–4897. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.10.4894-4897.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu WH, Kumar A, Peterhoff C, Shapiro Kulnane L, Uchiyama Y, Lamb BT, Cuervo AM, Nixon RA. Autophagic vacuoles are enriched in amyloid precursor protein-secretase activities: implications for beta-amyloid peptide over-production and localization in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2531–2540. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. Autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. Cell Struct Funct. 2002;27:421–429. doi: 10.1247/csf.27.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassa A, Roux MP, Attaix D, Bechet DM. Class III phosphoinositide 3-kinase-Beclin1 complex mediates the amino acid-dependent regulation of autophagy in C2C12 myotubes. Biochem J. 2003;376:577–586. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petiot A, Pattingre S, Arico S, Meley D, Codogno P. Diversity of signaling controls of macroautophagy in mammalian cells. Cell Struct Funct. 2002;27:431–441. doi: 10.1247/csf.27.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattingre S, Tassa A, Qu X, Garuti R, Liang XH, Mizushima N, Packer M, Schneider MD, Levine B. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell. 2005;122:927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fall CP, Bennett JP., Jr Characterization and time course of MPP+-induced apoptosis in human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. J Neurosci Res. 1999;55:620–628. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990301)55:5<620::AID-JNR9>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie YX, Bezard E, Zhao BL. Investigating the receptor-independent neuroprotective mechanisms of nicotine in mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32405–32412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504664200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulich SM, Chu CT. Sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation by 6-hydroxydopamine: implications for Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem. 2001;77:1058–1066. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike M, Shibata M, Waguri S, Yoshimura K, Tanida I, Kominami E, Gotow T, Peters C, Figura KV, Mizushima N, Saftig P, Uchiyama Y. Participation of autophagy in storage of lysosomes in neurons from mouse models of neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses (Batten disease). Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1713–1728. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61253-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CT, Everiss KD, Batra S, Wikstrand CJ, Kung H-J, Bigner DD. Receptor dimerization is not a factor in the signalling activity of a transforming variant epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFRvIII). Biochem J. 1997;324:855–861. doi: 10.1042/bj3240855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulich SM, Chu CT. Role of reactive oxygen species in ERK phosphorylation and 6-hydroxydopamine cytotoxicity. J Biosci. 2003;28:83–89. doi: 10.1007/BF02970136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callio J, Oury TD, Chu CT. Manganese superoxide dismutase protects against 6-hydroxydopamine injury in mouse brains. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18536–18542. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413224200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munafó DB, Colombo MI. A novel assay to study autophagy: regulation of autophagosome vacuole size by amino acid deprivation. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3619–3629. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.20.3619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CT, Zhu JH, Cao G, Signore A, Wang S, Chen J. Apoptosis inducing factor mediates caspase-independent 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium toxicity in dopaminergic cells. J Neurochem. 2005;94:1685–1695. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederbick A, Kern HF, Elsasser HP. Monodansylcadaverine (MDC) is a specific in vivo marker for autophagic vacuoles. Eur J Cell Biol. 1995;66:3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemann A, Takatsuki A, Elsasser HP. The lysosomotropic agent monodansylcadaverine also acts as a solvent polarity probe. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48:251–258. doi: 10.1177/002215540004800210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sou YS, Tanida I, Komatsu M, Ueno T, Kominami E. Phosphatidylserine in addition to phosphatidylethanolamine is an in vitro target of the mammalian Atg8 modifiers, LC3, GABARAP, and GATE-16. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3017–3024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505888200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma K, Tanida I, Shirato I, Ueno T, Takahara H, Nishitani T, Kominami E, Tomino Y. MAP-LC3, a promising autophagosomal marker, is processed during the differentiation and recovery of podocytes from PAN nephrosis. FASEB J. 2003;17:1165–1167. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0580fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T, Kominami E, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000;19:5720–5728. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanida I, Minematsu-Ikeguchi N, Ueno T, Kominami E. Lysosomal turnover, but not a cellular level, of endogenous LC3 is a marker for autophagy. Autophagy. 2005;1:84–91. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.2.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto A, Tagawa Y, Yoshimori T, Moriyama Y, Masaki R, Tashiro Y. Bafilomycin A1 prevents maturation of autophagic vacuoles by inhibiting fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes in rat hepatoma cell line, H-4-II-E cells. Cell Struct Funct. 1998;23:33–42. doi: 10.1247/csf.23.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shacka JJ, Klocke BJ, Shibata M, Uchiyama Y, Datta G, Schmidt RE, Roth KA. Bafilomycin A1 inhibits chloroquine-induced death of cerebellar granule neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1125–1136. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.018408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulin-Levasseur M, Chen G, Lariviere C. The 2G2 antibody recognizes an acidic 110-kDa human mitochondrial protein. Histochem J. 1998;30:617–625. doi: 10.1023/a:1003577609799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seglen PO, Gordon PB, Grinde B, Solheim A, Kovacs AL, Poli A. Inhibitors and pathways of hepatocytic protein degradation. Acta Biol Med Ger. 1981;40:1587–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blommaart EF, Krause U, Schellens JP, Vreeling-Sindelarova H, Meijer AJ. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors wortmannin and LY294002 inhibit autophagy in isolated rat hepatocytes. Eur J Biochem. 1997;243:240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.0240a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petiot A, Ogier-Denis E, Blommaart EF, Meijer AJ, Codogno P. Distinct classes of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinases are involved in signaling pathways that control macroautophagy in HT-29 cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:992–998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattingre S, Bauvy C, Codogno P. Amino acids interfere with the ERK1/2-dependent control of macroautophagy by controlling the activation of Raf-1 in human colon cancer HT-29 cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16667–16674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210998200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Santos C, Ferrer I, Reiriz J, Vinals F, Barrachina M, Ambrosio S. MPP+ increases alpha-synuclein expression and ERK/MAP-kinase phosphorylation in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Brain Res. 2002;935:32–39. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Matsui M, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. In vivo analysis of autophagy in response to nutrient starvation using transgenic mice expressing a fluorescent autophagosome marker. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:1101–1111. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X, Yu J, Bhagat G, Furuya N, Hibshoosh H, Troxel A, Rosen J, Eskelinen EL, Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, Cattoretti G, Levine B. Promotion of tumorigenesis by heterozygous disruption of the beclin 1 autophagy gene. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1809–1820. doi: 10.1172/JCI20039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Z, Jin S, Yang C, Levine AJ, Heintz N. Beclin 1, an autophagy gene essential for early embryonic development, is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15077–15082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2436255100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farre JC, Subramani S. Peroxisome turnover by micropexophagy: an autophagy-related process. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:515–523. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leão AN, Kiel JA. Peroxisome homeostasis in Hansenula polymorpha. FEMS Yeast Res. 2003;4:131–139. doi: 10.1016/S1567-1356(03)00070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair U, Klionsky DJ. Molecular mechanisms and regulation of specific and nonspecific autophagy pathways in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41785–41788. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolkovsky AM, Xue L, Fletcher GC, Borutaite V. Mitochondrial disappearance from cells: a clue to the role of autophagy in programmed cell death and disease? Biochimie. 2002;84:233–240. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(02)01371-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horbinski C, Chu CT. Kinase signaling cascades in the mitochondrion: a matter of life or death. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CT, Levinthal DJ, Kulich SM, Chalovich EM, DeFranco DB. Oxidative neuronal injury: the dark side of ERK1/2. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:2060–2066. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J-H, Kulich SM, Oury TD, Chu CT. Cytoplasmic aggregates of phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase in Lewy body diseases. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:2087–2098. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64487-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellington AA, Berhow MA, Singletary KW. Inhibition of Akt signaling and enhanced ERK1/2 activity are involved in induction of macroautophagy by triterpenoid B-group soyasaponins in colon cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:298–306. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsztein DC, DiFiglia M, Heintz N, Nixon RA, Qin Z-H, Ravikumar B, Stefanis L, Tolkovsky A. Autophagy and its possible roles in nervous system diseases, damage and repair. Autophagy. 2005;1:11–22. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.1.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Yuan J. Autophagy in cell death: an innocent convict? J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2679–2688. doi: 10.1172/JCI26390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debnath J, Baehrecke EH, Kroemer G. Does autophagy contribute to cell death? Autophagy. 2005;1–2:66–74. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.2.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codogno P, Meijer AJ. Autophagy and signaling: their role in cell survival and cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12(Suppl 2):1509–1518. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CT. Autophagic stress in neuronal injury and disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:423–432. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000229233.75253.be. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa H, Miyashita T, Nakano Y, Yamamoto D. HSpin1, a transmembrane protein interacting with Bcl-2/Bcl-xL, induces a caspase-independent autophagic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:798–807. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice E, Jerome WG, Yoshimori T, Mizushima N, Denison MR. Coronavirus replication complex formation utilizes components of cellular autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10136–10141. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306124200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller JN, Dimayuga E, Chen Q, Thorpe J, Gee J, Ding Q. Autophagy, proteasomes lipofuscin, and oxidative stress in the aging brain. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2376–2391. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunk UT, Terman A. The mitochondrial-lysosomal axis theory of aging: accumulation of damaged mitochondria as a result of imperfect autophagocytosis. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:1996–2002. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baris O, Mirebeau-Prunier D, Savagner F, Rodien P, Ballester B, Loriod B, Granjeaud S, Guyetant S, Franc B, Houlgatte R, Reynier P, Malthiery Y. Gene profiling reveals specific oncogenic mechanisms and signaling pathways in oncocytic and papillary thyroid carcinoma. Oncogene. 2005;24:4155–4161. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]