Abstract

Aim: To review 66 children with obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) for whom a trial of nasal continuous positive airway pressure (nCPAP) was proposed.

Methods: Baseline sleep studies were performed to assess OSA severity; a trial of nCPAP was performed where moderate to severe OSA, not relieved by adenotonsillectomy, was found. The nCPAP trial was considered either technically successful (ST), if the child accepted the mask for sufficient time to determine nCPAP efficacy, or a technical failure (FT) if otherwise. Patients with an initial FT were offered a period of home acclimatisation to familiarise them with wearing the mask during sleep. ST patients in whom nCPAP was effective were established on long term therapy.

Results: Nasal CPAP trials were successful (ST) in 49/66 (74%) patients. Nasal CPAP efficacy could not be determined in the remaining 17 FT patients (26%), generally because of their poor nCPAP tolerance. These patients were subsequently considered for other treatment. A total of 42/49 (86%) ST patients were established on long term nCPAP therapy, 2/49 (4%) derived no benefit from nCPAP, while 5/49 (10%) refused long term nCPAP therapy. Of patients on long term nCPAP, the most frequently reported side effects were skin irritation and nasal dryness; however, these were not serious enough to require any patients to discontinue therapy. A period of home acclimatisation was found to be effective in increasing nCPAP acceptance, with 26% of FT children being subsequently successfully reassessed for nCPAP.

Conclusion: The use of nCPAP was feasible in a significant proportion of a paediatric OSA population. Failure was usually because of the child's intolerance of the nCPAP equipment. Nasal CPAP was an effective treatment in the majority of patients where it could be assessed, and was adopted as a long term therapy in most cases. We have successfully used nCPAP to treat OSA across a wide range of ages. Motivated parents and skilled support staff have proved essential for the success of nCPAP in a paediatric setting.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (202.1 KB).

Figure 1 .

An infant undergoing a sleep study with nasal CPAP. The CPAP mask consists a rigid plastic frame with a soft silicone nasal cushion. The mask is held in place over the nose by a set of headgear with a three-point fixing to the mask frame using adjustable Velcro straps. The CPAP pressure is applied from a flow generator located at the cot side (out of picture) via the corrugated tubing, seen to the patient's right. Mask pressure is monitored during the CPAP trial via the narrow manometer tubing connected to the CPAP mask. The respiband monitoring respiratory movements is evident round the chest, an oximeter probe is attached to the right foot, and the ECG leads can be seen exiting from the child's clothes.

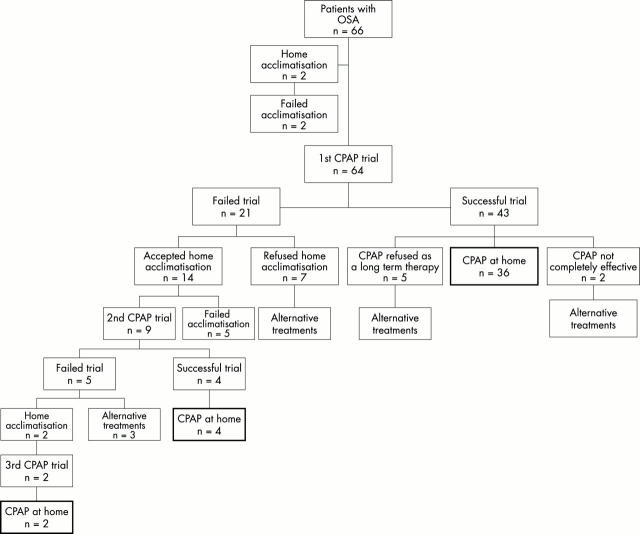

Figure 2 .

Flow diagram showing the history of 66 patients with OSA in which an nCPAP trial was suggested. The outlined boxes indicate the patients that were established on nCPAP therapy at home. For children that failed to be treated with nCPAP, alternative treatments such as nasopharyngeal prong, supplemental oxygen, and craniofacial surgery were used. One child underwent tracheostomy for acute respiratory failure and was subsequently ventilated with BiPAP via tracheostomy. One child underwent adenotonsillectomy after a period of stabilisation with CPAP.

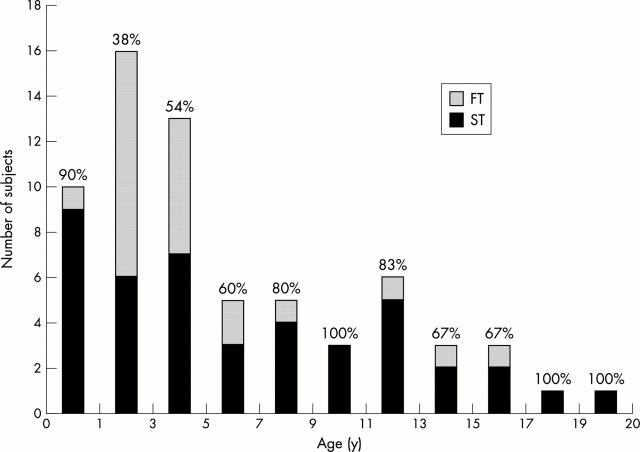

Figure 3 .

Number of children with successful nCPAP trials (ST) and with failed trials (FT), broken down by the age at outset of their nCPAP trial. Percentages represent success rate for each age group.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Downey R., 3rd, Perkin R. M., MacQuarrie J. Nasal continuous positive airway pressure use in children with obstructive sleep apnea younger than 2 years of age. Chest. 2000 Jun;117(6):1608–1612. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.6.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonsalez S., Thompson D., Hayward R., Lane R. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea using nasal CPAP in children with craniofacial dysostoses. Childs Nerv Syst. 1996 Nov;12(11):713–719. doi: 10.1007/BF00366156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilleminault C., Nino-Murcia G., Heldt G., Baldwin R., Hutchinson D. Alternative treatment to tracheostomy in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: nasal continuous positive airway pressure in young children. Pediatrics. 1986 Nov;78(5):797–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilleminault C., Pelayo R., Clerk A., Leger D., Bocian R. C. Home nasal continuous positive airway pressure in infants with sleep-disordered breathing. J Pediatr. 1995 Dec;127(6):905–912. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui S., Wing Y. K., Kew J., Chan Y. L., Abdullah V., Fok T. F. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in a family with Crouzon's syndrome. Sleep. 1998 May 1;21(3):298–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K. K., Riley R. W., Guilleminault C. An unreported risk in the use of home nasal continuous positive airway pressure and home nasal ventilation in children: mid-face hypoplasia. Chest. 2000 Mar;117(3):916–918. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.3.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus C. L. Advances in management of sleep apnea syndromes in infants and children. Pediatr Pulmonol Suppl. 1999;18:188–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus C. L. Management of obstructive sleep apnea in childhood. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 1997 Nov;3(6):464–469. doi: 10.1097/00063198-199711000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus C. L., Omlin K. J., Basinki D. J., Bailey S. L., Rachal A. B., Von Pechmann W. S., Keens T. G., Ward S. L. Normal polysomnographic values for children and adolescents. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992 Nov;146(5 Pt 1):1235–1239. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.5_Pt_1.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus C. L., Ward S. L., Mallory G. B., Rosen C. L., Beckerman R. C., Weese-Mayer D. E., Brouillette R. T., Trang H. T., Brooks L. J. Use of nasal continuous positive airway pressure as treatment of childhood obstructive sleep apnea. J Pediatr. 1995 Jul;127(1):88–94. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara F., Sullivan C. E. Obstructive sleep apnea in infants and its management with nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Chest. 1999 Jul;116(1):10–16. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper A. J., Stewart D. A. An overview of nasal CPAP therapy in the management of obstructive sleep apnea. Ear Nose Throat J. 1999 Oct;78(10):776-8, 781-2, 784-90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rains J. C. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in pediatric patients. Behavioral intervention for compliance with nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1995 Oct;34(10):535–541. doi: 10.1177/000992289503401005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen C. L., D'Andrea L., Haddad G. G. Adult criteria for obstructive sleep apnea do not identify children with serious obstruction. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992 Nov;146(5 Pt 1):1231–1234. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.5_Pt_1.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C. F., Lowe A. A., Fleetham J. A. Nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy for obstructive sleep apnea in Hallermann-Streiff syndrome. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1990 Feb;29(2):122–124. doi: 10.1177/000992289002900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Nowara W. W. Continuous positive airway pressure for long-term treatment of sleep apnea. Am J Dis Child. 1984 Jan;138(1):82–84. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1984.02140390070021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan C. E., Issa F. G., Berthon-Jones M., Eves L. Reversal of obstructive sleep apnoea by continuous positive airway pressure applied through the nares. Lancet. 1981 Apr 18;1(8225):862–865. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)92140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan C. E., McNamara F., Waters K. A., Harris M., Everett F., Seton C., Bruderer J. Nasal CPAP: use in the management of infantile apnea. Sleep. 1993 Dec;16(8 Suppl):S108–S113. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.suppl_8.s108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirosh E., Tal Y., Jaffe M. CPAP treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea and neurodevelopmental deficits. Acta Paediatr. 1995 Jul;84(7):791–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1995.tb13758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters K. A., Everett F. M., Bruderer J. W., Sullivan C. E. Obstructive sleep apnea: the use of nasal CPAP in 80 children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995 Aug;152(2):780–785. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.2.7633742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters K. A., Everett F., Bruderer J., MacNamara F., Sullivan C. E. The use of nasal CPAP in children. Pediatr Pulmonol Suppl. 1995;11:91–93. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950191145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters K., Everett F., Harris M. A., Sullivan C. E. Use of nasal mask CPAP instead of tracheostomy for palliative care in two children. J Paediatr Child Health. 1994 Apr;30(2):179–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]