Summary

Listeria monocytogenes grows in the cytosol of mammalian cells and spreads from cell to cell without exiting the intracellular milieu. During cell–cell spread, bacteria become transiently entrapped in double-membrane vacuoles. Escape from these vacuoles is mediated in part by a bacterial phospholipase C (PC-PLC), whose activation requires cleavage of an N-terminal peptide. PC-PLC activation occurs in the acidified vacuolar environment. In this study, the pH-dependent mechanism of PC-PLC activation was investigated by manipulating the intracellular pH of the host. PC-PLC secreted into infected cells was immunoprecipitated, and both forms of the protein were identified by SDS–PAGE fluorography. PC-PLC activation occurred at pH 7.0 and lower, but not at pH 7.3. Total amounts of PC-PLC secreted into infected cells increased several-fold over controls within 5 min of a decrease in intracellular pH, and the active form of PC-PLC was the most abundant species detected. Bacterial release of active PC-PLC was dependent on Mpl, a bacterial metalloprotease that processes the proform (proPC-PLC), and did not require de novo protein synthesis. The amount of proPC-PLC released in response to a decrease in pH was the same in wild-type and Mpl-minus-infected cells. Immunofluorescence detection of PC-PLC in infected cells was performed. When fixed and permeabilized infected cells were treated with a bacterial cell wall hydrolase, over 97% of wild-type and Mpl-minus bacteria stained positively for PC-PLC, in contrast to less than 5% in untreated cells. These results indicate that intracellular bacteria carry pools of proPC-PLC. Upon cell–cell spread, a decrease in vacuolar pH triggers Mpl activation of proPC-PLC, resulting in bacterial release of active PC-PLC.

Introduction

Listeria monocytogenes is a Gram-positive, facultative intracellular bacterium that causes sepsis and infections of the central nervous system in susceptible individuals and abortion in pregnant women. As a food-borne pathogen, the bacterium has emerged as a significant public health problem and has caused several outbreaks in the USA and Europe (Farber and Peterkin, 1991; Schlech, 1997; CDC, 1999).

L. monocytogenes multiplies in the cytosol of mammalian cells and subverts host cell biological pathways to spread from cell to cell without leaving the intracellular milieu. The morphological steps of intracellular growth and cell–cell spread of L. monocytogenes have been characterized (Tilney and Portnoy, 1989; Mounier et al., 1990). After uptake, the bacterium rapidly mediates lysis of the vacuolar membrane and immediately initiates intracytosolic multiplication. Asymmetric polymerization of host actin at the bacterial surface results in actin-based motility, facilitating direct cell–cell spread (Tilney and Portnoy, 1989; Dabiri et al., 1990; Mounier et al., 1990; Theriot et al., 1992). During cell–cell spread, bacteria become transiently entrapped in double-membrane vacuoles, also called secondary vacuoles, from which they must escape to begin a new intracellular growth cycle. The specialized strategy by which L. monocytogenes spreads from cell to cell facilitates propagation of the bacterial infection without exposure to the host's humoral immune response, and could be the mechanism by which bacteria gain access to the central nervous system. Indeed, primary cultures of spinal neurons can be effectively infected only when co-cultivated with infected macrophages, and the infection process is dependent on ActA, the bacterial surface protein mediating actin polymerization, indicating that infection occurs by direct cell–cell spread (Dramsi et al., 1998).

Among bacterial factors mediating escape from double-membrane vacuoles are two phospholipases of the C type (PLC) and a metalloprotease (Mpl). PI-PLC is a phosphatidylinositol-specificc PLC encoded by plcA and PC-PLC is a broad-range PLC encoded by plcB. The two PLCs and Mpl are clearly important in the spread of an infection because mutants lacking either of the PLCs, Mpl or both PLCs form small plaques in confluent monolayers of murine fibroblasts, presumably because they are less efficient in escaping from secondary vacuoles (Vazquez-Boland et al., 1992; Camilli et al., 1993; Smith et al., 1995; Marquis et al., 1997). In the mouse macrophage-like cell line J774, a plcB mutant accumulates in double-membrane vacuoles, emphasizing the importance of PC-PLC in bacterial escape from secondary vacuoles (Vazquez-Boland et al., 1992). PC-PLC is also required for heterologous cell–cell spread from macrophages to endothelial cells (Greiffenberg et al., 1998). More recently, the role of PC-PLC in bacterial cell–cell spread was tested in vivo using a mouse model of cerebral listeriosis. In that model, a plcB mutant showed a significantly delayed intra-cerebral spread, indicating that PC-PLC was required for efficient and fulminant cerebral infection (Schlüter et al., 1998).

PC-PLC is secreted as an inactive enzyme (proPC-PLC), and activation requires cleavage of a 24-amino-acid N-terminal peptide (Raveneau et al., 1992; Niebuhr et al., 1993). ProPC-PLC processing is mediated by Mpl (Poyart et al., 1993), although in infected J774 cells proPC-PLC processing can also be mediated by a thiol protease presumably of host origin (Marquis et al., 1997). Intracellular processing of proPC-PLC by either pathway is dependent on localization of the bacterium to a secondary vacuole and on vacuolar acidification (Marquis et al., 1997). In the absence of bacterial cell–cell spread, a small amount of proPC-PLC is secreted in the cytosol of infected host cells, and is rapidly degraded by the proteasome. Proteolytic activation of cytosolic proPC-PLC is not observed even in the absence of protea-some activity (Marquis et al., 1997). These results strongly emphasize a role for pH in the intracellular activation of PC-PLC.

In the present study, we aimed at defining the pH-dependent mechanism of PC-PLC activation during intracellular growth. We report that during intracellular infection bacteria multiplying in the host cytosol carry pools of proPC-PLC, suggesting that proPC-PLC is initially sorted to a bacterial compartment that is as yet unidentified. Acidification of the host compartment in which the bacteria are confined triggers rapid Mpl-mediated activation and release of active PC-PLC. PC-PLC was cytotoxic when prematurely activated and released in the host cytosol as opposed to in secondary vacuoles. The significance of these findings with regard to the cell biology of L. monocytogenes intracellular life may be very important.

Results

The effect of pH on release of bacteria-associated PC-PLC

Bacterial cell–cell spread and vacuolar acidification is a prerequisite to proPC-PLC proteolytic activation during intracellular infection. We have previously shown that cytosolic bacteria secrete small amounts of proPC-PLC that are rapidly degraded by the proteasome, and that active PC-PLC is only generated by bacteria located in acidified secondary vacuoles (Marquis et al., 1997). An experimental approach was designed to define the pH at which proPC-PLC becomes activated. Infected J774 cells were pulse labelled with [35S]-methionine and were chased in buffer containing nigericin (10 μM), cold methio-nine (2 mM) and chloramphenicol (20 μgml−1). Nigericin is a potassium ionophore that allows equilibration of pH across all membranes. At the end of the chase, infected cells were lysed and both forms of PC-PLC were immuno-precipitated as has been previously described (Marquis et al., 1997). Remarkably, the total amount of PC-PLC detected during the chase increased several-fold with a decrease in cytosolic pH, suggesting either that intracellular bacteria carried pools of PC-PLC or that modification of host intracellular pH triggered a burst of bacterial protein synthesis before inhibition by chloramphenicol. If the former is correct, it would indicate that pH regulates release of bacteria-associated PC-PLC.

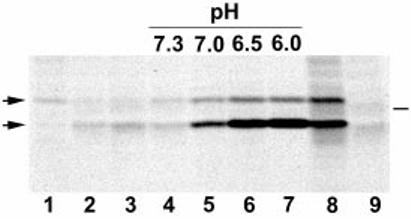

To address whether intracellular pH regulates release of bacteria-associated PC-PLC, infected J774 cells were pulse labelled for 10 min and chased with cold methionine and chloramphenicol to block bacterial protein synthesis. Fifteen minutes into the chase, the medium was replaced with nigericin-containing buffer solutions adjusted at pH 7.3, pH 7.0, pH 6.5 or pH 6.0 and supplemented with chloramphenicol and cold methionine. The cytosol of mammalian cells is normally at pH 7.2 (Alberts et al., 1994). The results show that, as the pH decreased from pH 7.0 to pH 6.0, the amount of PC-PLC immunoprecipitated from infected cell lysates increased, and the active form of PC-PLC was the most abundant species detected (Fig. 1). A minor increase in the amount of the proform, but no increase in the amount of the active form, was detected in nigericin-treated infected cells perfused with buffer pH 7.3, indicating that nigericin itself did not have a significant effect on bacterial release of PC-PLC. These results strongly suggest that intracellular bacteria carry pools of PC-PLC and that pH controls the release of bacteria-associated PC-PLC.

Fig. 1.

pH-regulated release of L. monocytogenes PC-PLC during intracellular infection. Infected J774 cells were pulse labelled with [35S]-methionine for either 10 (lanes 1–7) or 40 min (lanes 8–9) at 4 h after infection and chased with cold methionine and chloramphenicol for 15 (lane 2) or 30 min (lanes 3–7). Samples 2 and 3 were chased in tissue culture medium. Samples 4–7 were initially chased for 15 min in tissue culture medium, then perfused with nigericin-containing buffer adjusted to various pH levels for 15 min. Samples 8 and 9 were not chased. PC-PLC was immunoprecipitated using affinity-purified antibodies, and proteins were fractionated using SDS–PAGE. PC-PLC was detected by fluorography. Lanes 1–8, cells infected with wild-type L. monocytogenes (10403S); Lane 9, cells infected with an isogenic plcB deletion mutant, DP-L1935. Left side, arrows point at proPC-PLC (upper band) and active PC-PLC (lower band). Right side, bar indicates the migration point of the 31 kDa protein marker.

Kinetics of pH-regulated release of PC-PLC

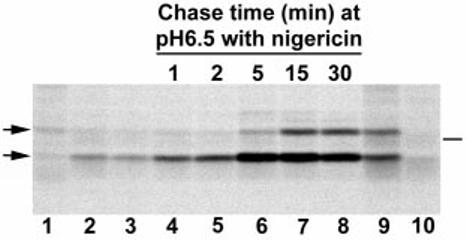

A time-course experiment was performed to determine the kinetics of PC-PLC release in response to acidification. The experiment was performed as described above with some modifications. Fifteen minutes into the chase, samples were perfused with nigericin-containing buffer adjusted to pH 6.5 for periods of 1, 2, 5, 15 or 30 min. The results, shown in Fig. 2, demonstrate that at pH 6.5 increased amounts of active PC-PLC were observed within 1 min of a decrease in pH, and that maximum amounts were released within 5 min of a decrease in pH. The proform was secreted at a much slower rate, suggesting either that the proform is not as competent as the active form for secretion at pH 6.5 or that the enzymatic activity of the proPC-PLC-processing enzymes decreases with time, allowing the proform to accumulate. The latter could be the result of a short half-life of the PC-PLC-activating proteases.

Fig. 2.

Kinetics of bacterial release of PC-PLC in response to a decrease in intracellular pH. Infected J774 cells were pulse labelled with [35S]-methionine for either 10 (lanes 1–8) or 30 min (lanes 9–10) at 4 h after infection and were chased with cold methionine and chloramphenicol. Samples 2 and 3 were chased in tissue culture medium for 15 and 30 min respectively. Samples 4–8 were initially chased for 15 min in tissue culture medium, then perfused with nigericin-containing buffer adjusted to pH 6.5 for various periods of time. Samples 9 and 10 were not chased. PC-PLC was immunoprecipitated using affinity-purified antibodies, and proteins were fractionated using SDS–PAGE. PC-PLC was detected by fluorography. Lanes 1–9, cells infected with wild-type L. monocytogenes (10403S). Lane 10, cells infected with an isogenic plcB deletion mutant, DP-L1935. Left side, arrows point at proPC-PLC (upper band) and active PC-PLC (lower band). Right side, bar indicates the migration point of the 31 kDa protein marker.

PC-PLC association with intracellular bacteria

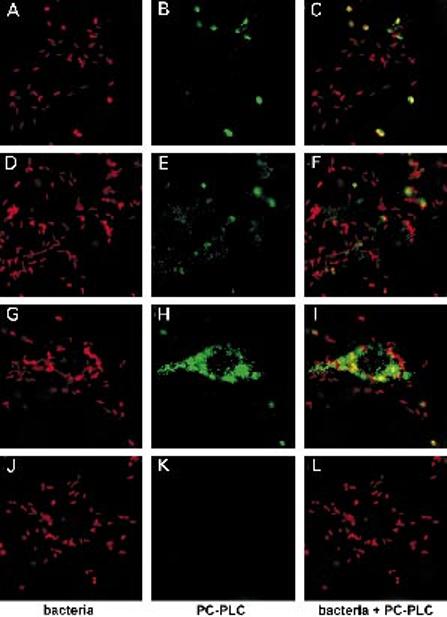

Immunofluorescence microscopy studies have revealed that PC-PLC associates only with bacteria in secondary vacuoles, which account for ≤ 10% of the total number of intracellular bacteria at 5–5.5 h after infection (Marquis et al., 1997) (Fig. 3A-C). Based on the results reported above, we hypothesized that all intracellular bacteria carry pools of PC-PLC sequestered in a bacterial compartment inaccessible to antibodies. To test that hypothesis, infected cells were treated for 5 min with nigericin-containing buffer adjusted to pH 6.5, fixed and stained for detection of PC-PLC by immunofluorescence. This treatment resulted in massive release of PC-PLC in the host cell cytosol (Fig. 3G-I). Massive cytosolic release of PC-PLC was not an indirect result of the nigericin treatment because cells treated with nigericin buffer pH 7.3 showed little increase in cytosolic staining for PC-PLC (Fig. 3D-F). Interestingly, PC-PLC appears to be absent from the periphery of infected cells treated with nigericin/pH 6.5 buffer (Fig. 3H-I). As shown in a following experiment, release of active PC-PLC in the host cytosol affects the integrity of the cell membrane. Perhaps, PC-PLC is partially lost when the cells are washed before fixation.

Fig. 3.

Immunofluorescence staining of L. monocytogenes and PC-PLC in infected J774 cells. At 5.5 h after infection, infected cells were perfused for 5 min with nigericin-containing buffer adjusted to pH 7.3 (D–F) or pH 6.5 (G–L). Cells were fixed in formalin and were permeabilized with saponin. Bacteria and PC-PLC were detected with specific antibodies, as described in Experimental procedures, and were counterstained with rhodamine (bacteria) or fluorescein (PC-PLC) conjugates.

A–C. Untreated wild-type infected J774 cells.

D–F. pH 7.3 treated wild-type infected cells.

G–I. pH 6.5 treated wild-type infected cells.

J–L. pH 6.5 treated plcB-minus infected cells.

Each image represents a deconvolved 0.5 μm section; 10 μm bar in C.

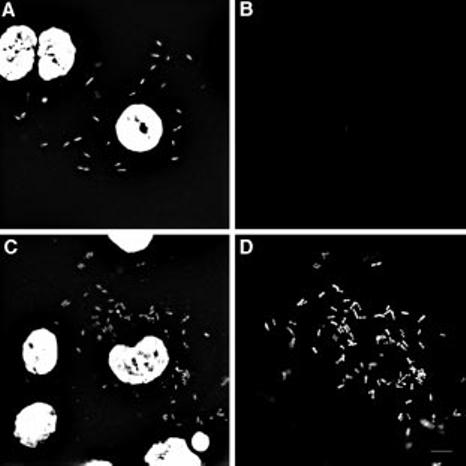

Definitive confirmation that intracellular bacteria carried pools of PC-PLC is shown in Fig. 4. In this experiment, infected cells were fixed 4 h after infection, permeabilized, treated with mutanolysin to digest the bacterial cell wall and stained for PC-PLC. Results, shown in Fig. 4, confirmed that intracellular bacteria carry pools of PC-PLC. Quantification data from three independent experiments revealed that 97.2 ± 1.5% (SD) of the bacteria stained positive for PC-PLC after the mutanolysin treatment, in contrast to less than 5% before treatment. Cells infected with the plcB mutant and treated with mutanolysin did not stain for PC-PLC. These results suggested that, during intracellular bacterial growth, PC-PLC is synthesized and sorted to an undetermined bacterial compartment until a decrease in pH triggers its release.

Fig. 4.

Intracellular bacteria have pools of PC-PLC. At 4 h after infection with L. monocytogenes, infected cells were fixed in acetone/methanol. Samples were reacted for 30 min at 37°C with (C and D) or without (A and B) mutanolysin as described in Experimental procedures. Bacteria and host cell nuclei were detected by staining DNA with bisBenzimide (Hoechst 33258) (A and C) and PC-PLC was detected with affinity-purified antibodies and counterstained with a fluorescein conjugate (B and D). Each image represents a deconvolved 0.5 mm section; 10 mm bar in D.

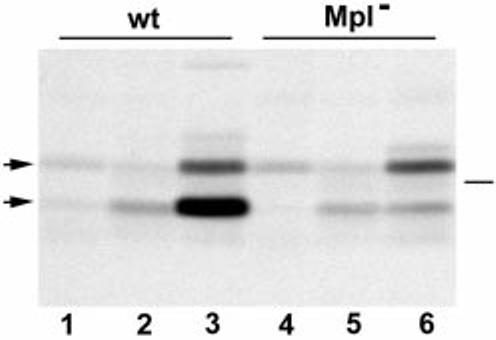

The role of Mpl in pH-regulated release of PC-PLC

We have previously shown that intracellular activation of proPC-PLC can be mediated by Mpl and by a cysteine protease, which we speculate is of lysosomal origin (Marquis et al., 1997). In that study, active PC-PLC was immuno-precipitated from J774 cells infected with either wild-type strain or the Mpl-minus mutant strain, and inhibition of proPC-PLC activation by an inhibitor of lysosomal thiol cathepsins was observed only in cells infected with the Mpl-minus strain. Therefore, if the nigericin/acid pH treatment triggers release of active PC-PLC from cytosolic bacteria, we would expect that under these conditions PC-PLC activation would be dependent on Mpl, as the large majority (≥ 90%) of intracellular bacteria were in the cytosol at the time the cells were treated. The role of Mpl in the bacterial release of active PC-PLC in response to pH was investigated. J774 cells were infected with either wild-type L. monocytogenes or an isogenic mpl deletion mutant, pulse labelled for 10 min and chased with cold methionine and chloramphenicol to block bacterial protein synthesis. Fifteen minutes into the chase, the cells were perfused with nigericin-containing buffer adjusted to pH 6.5 and both forms of PC-PLC were immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates. The results showed that release of active PC-PLC after acidification of the entire host cell is Mpl dependent (Fig. 5). The increased amount of proform detected was similar in cells infected with either bacterial strain and was several-fold less than the amount of active form detected in wild-type infected cells. This result suggested either that proteolytic activation of proPC-PLC is a prerequisite to efficient bacterial release of PC-PLC in response to a decrease in pH or that Mpl-minus bacteria do not carry a pool of proPC-PLC. To address that point, Mpl-minus-infected cells were fixed 4 h after infection, permeabilized, treated with mutanolysin to digest the bacterial cell wall and stained for PC-PLC. Results indicated that Mpl-minus bacteria carry pools of proPC-PLC. Quantification data from two independent experiments revealed that 4 h after infection 98.4% (100% and 96.5%) of the intracellular bacteria stained positive for PC-PLC after the mutanolysin treatment, in contrast to less than 5% before treatment. These results confirmed that intracellular bacteria carry pools of proPC-PLC and that Mpl-mediated activation of proPC-PLC is the pH-dependent rate-limiting step for efficient bacterial release of PC-PLC.

Fig. 5.

Mpl-dependent release of L. monocytogenes PC-PLC in infected J774 cells. Infected cells were pulse labelled with [35S]-methionine for 10 min (lanes 1–6) at 4 h after infection and chased with cold methionine and chloramphenicol. Samples 2 and 5 were chased for 15 min in tissue culture medium. Samples 3 and 6 were initially chased for 15 min in tissue culture medium, then perfused with nigericin-containing buffer adjusted to pH 6.5 during the last 15 min of the chase. PC-PLC was immunoprecipitated using affinity-purified antibodies, and proteins were fractionated using SDS–PAGE. PC-PLC was detected by fluorography. Lanes 1–3, cells infected with L. monocytogenes 10403S. Lanes 4–6, cells infected with an isogenic mpl deletion mutant DP-L2296. Left side, arrows point at proPC-PLC (upper band) and active PC-PLC (lower band). Right side, bar indicates the migration point of the 31 kDa protein marker.

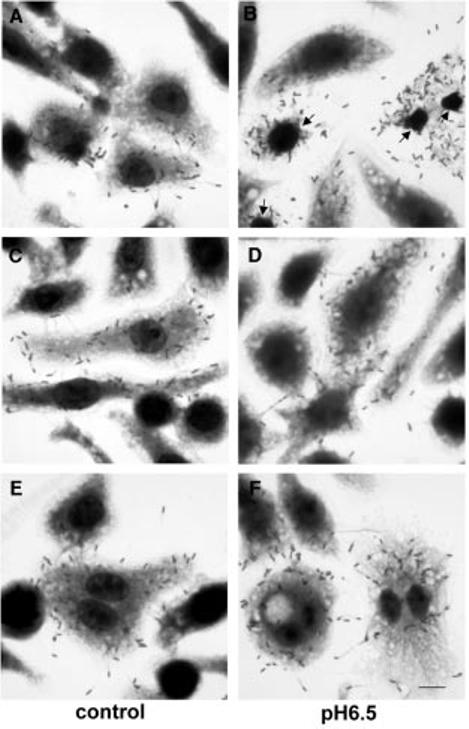

Importance of the pH-regulated release of PC-PLC during bacterial infection

Our observations indicated that intracellular bacteria carry pools of proPC-PLC and that release of active PC-PLC from bacteria is tightly regulated by pH. We investigated the consequences of releasing active PC-PLC in the cytosol of infected cells. Infected cells were treated for 5 min with nigericin-containing buffer adjusted to pH 6.5, fixed and stained for bright-field microscopy. The release of active PC-PLC in the host cytosol was cytotoxic, as defined by the appearance of pycnotic nuclei and an apparent decrease in cytosolic density (Fig. 6B). In addition, protrusions formed by bacteria in movement were no longer apparent, as if membranes had been dissolved and actin tails depolymerized. This cytotoxic effect was not due to the treatment with nigericin buffer pH 6.5, as uninfected surrounding cells were not affected. Quantification of four independent experiments indicated a 50-fold increase in cytotoxicity as a result of a decrease in pH in wild-type infected cells, as opposed to three- and fivefold increases in cytotoxicity for Mpl-minus- and PC-PLC-minus-infected cells respectively (Table 1). These results further emphasize the importance of the mechanism regulating activation and release of PC-PLC in infected cells.

Fig. 6.

PC-PLC cytotoxicity for J774 cells. Infected cells were perfused for 5 min with nigericin-containing buffer adjusted to pH 6.5, fixed and stained with Diff-Quick (Dade Diagnostics). Cells were infected with wild-type L. monocytogenes (A and B), an isogenic plcB deletion mutant DP-L1935 (C and D) and an isogenic mpl deletion mutant DP-L2296 (E and F).

A, C and E. Untreated controls.

B, D and F. Acidified samples.

Arrows in B point at pycnotic nuclei. Notice that uninfected cells in B look normal; 10 μm bar in F

Table 1.

Quantification of PC-PLC cytotoxicity for J774 cells.

| Strain | Controla | Treatedb |

|---|---|---|

| WT | 1.25 ± 0.96c | 63.75 ± 13.72 |

| Δ plcB | 3.75 ± 3.30 | 11.25 ± 6.60 |

| Δ mpl | 1.75 ± 0.96 | 9.00 ± 2.94 |

Infected J774 cells were evaluated for signs of cytotoxicity at 5 h after infection as described in Experimental procedures. A minimum of 100 primary infected cells were evaluated per sample per experiment. The percentage of infected cells with loss of cytosol density, loss of bacterial protrusions and nucleus condensation was determined.

Infected J774 cells were perfused with nigericin-containing buffer pH 6.5 for 5 min at 5 h after infection and evaluated for signs of cytotoxicity.

Data are reported in percentages; means of four experiments ± standard deviations.

Discussion

The results of this study show that, during intracellular growth of L. monocytogenes, bacteria contain pools of PC-PLC and that a decrease in pH triggers bacterial release of the enzyme, primarily in its active form. pH-regulated release of active PC-PLC occurred within 5 min of a decrease in pH of less than one pH unit and was dependent on Mpl, a bacterial protease known to activate proPCPLC. Release of the proform in response to a decrease in pH was slower and to a much lesser extent than that of the active form. Two major conclusions can be drawn from these results. First, proPC-PLC is bacteria-associated during intracellular growth. Second, during bacterial cell–cell spread, a decrease in vacuolar pH triggers Mpl activation of proPC-PLC and bacterial release of active PC-PLC.

L. monocytogenes spreads from cell to cell without exposure to the extracellular milieu (Tilney and Portnoy, 1989). In the process of spreading, bacteria become transiently confined to double-membrane vacuoles, also called secondary vacuoles. The molecular and cellular mechanisms that govern bacterial escape from double-membrane vacuoles are just beginning to be defined. PC-PLC, a bacterially secreted phospholipase C, is capable of hydrolysing all of the phospholipids found in mammalian cells (Geoffroy et al., 1991; Goldfine et al., 1993) and is required for efficient bacterial escape from secondary vacuoles (Vazquez-Boland et al., 1992). PC-PLC is secreted as a proenzyme and activation requires proteolytic cleavage of an N-terminal peptide (Raveneau et al., 1992; Niebuhr et al., 1993). Recently, we have shown that intracellular activation of proPC-PLC is mediated by Mpl, a bacterial metalloprotease, and by a cysteine protease presumably of host lysosomal origin (Marquis et al., 1997). This activation process occurs during cell–cell spread when bacteria are located in vacuoles and is dependent on vacuolar acidification. In this study, we have begun to investigate the intracellular pH-dependent mechanism of PC-PLC activation.

PC-PLC is encoded by the plcB gene, which is part of an operon and located immediately downstream of the actA gene (Vazquez-Boland et al., 1992). The actA promoter is strongly activated in the host cell cytosol and translation of actA occurs as early as 15 min after infection (Freitag and Jacobs, 1999; Moors et al., 1999). Results from the present investigation are consistent with plcB gene expression being co-regulated with actA. During intracytosolic bacterial growth, a pool of proPC-PLC remains associated with the bacteria. Bacteria-associated proPC-PLC was not immunoprecipitated from lysates of infected cells, presumably because the protein was confined within the bacterial cells, which are very resistant to lysis.

We have previously observed that in the absence of bacterial cell–cell spread a small amount of proPC-PLC is secreted into the cytosol of infected cells and rapidly degraded by the proteasome. In the absence of protea-some activity, cytosolic proPC-PLC is stable, yet proteolytic activation of the phospholipase is not observed (Marquis et al., 1997). We speculated that proPC-PLC-activating proteases are either not present or not active in the cytosol of infected cells. Results from this investigation indicate that the lack of cytosolic activation of proPC-PLC was not due to the absence of Mpl but rather to environmental conditions that were not permissive for Mpl activity. Using the potassium ionophore nigericin, we have manipulated the cytosolic pH in order to mimic the acidified environment of the vacuole. Acidifying the cytosol of infected cells triggered release of active PC-PLC from cytosolic bacteria in an Mpl-dependent manner. This activation process was rapid and did not require de novo protein synthesis, suggesting that Mpl activation was the pH-dependent rate-limiting step for bacterial release of active PC-PLC. The absence of proPC-PLC activation by the Mpl-independent pathway was not surprising as this alternative pathway is believed to be mediated by a host lysosomal protease, which would not be present in the cytosol of mammalian cells.

Mpl and PC-PLC are predicted to be secreted as proenzymes by the general secretion pathway (Mengaud et al., 1991; Raveneau et al., 1992). Mpl activation presumably occurs by autocatalysis, as demonstrated for homologous bacterial metalloproteases (Van Wart and Birkedal-Hansen, 1990; Hase and Finkelstein, 1993), whereas proPC-PLC activation is mediated by Mpl (Poyart et al., 1993). Results from the present study suggested that Mpl and proPC-PLC are bacteria-associated and that Mpl-mediated activation of proPC-PLC is a prerequisite for efficient release of the protein. In the absence of Mpl, a decrease in cytosolic pH resulted in release of a relatively small amount of the bacteria-associated pool of proPC-PLC compared with the amount of active PC-PLC released in wild-type infected cells. However, previous results have shown that intracellular activation of proPC-PLC can also be mediated by a cysteine protease, presumably of host origin, suggesting that the proform must be secreted before activation by this mammalian protease. Indeed, the proform is secreted by intracellular bacteria, but in a very small amount (Marquis et al., 1997). Perhaps efficient bacterial release of the proform requires a more acidic pH than that tested in these experiments. Future studies will analyse the effects of a wider pH range on the bacterial release of proPC-PLC.

The bacterial compartments to which Mpl and proPC-PLC are initially sorted remain to be determined. An analysis of Mpl amino acid primary sequence revealed that Mpl could be cell wall anchored. Cell wall-anchored proteins of Gram-positive bacteria have common features at their C-terminus: a LPXTG sequence motif followed by a hydrophobic domain and a tail rich in positively charged amino acid residues (Schneewind et al., 1992; Navarre and Schneewind, 1999). The Mpl protein of L. monocytogenes has an imperfect LPXTG motif, LPITE, followed by a potential membrane-spanning domain of 20 amino acids and a positively charged C-terminal tail. On the contrary, PC-PLC has none of the characteristics of a cell wall-anchored protein. Interestingly, a chimeric construct of the L. monocytogenes PC-PLC leader sequence and propeptide fused to the Bacillus cereus orthologue does not seem to be retained by L. monocytogenes as large amounts of the proform can be immunoprecipitated from infected cells (Zuckert et al., 1998). This result suggests that neither the propeptide nor the N-terminus of the active form are necessary or sufficient to maintain the protein as bacteria associated. Perhaps proPC-PLC interacts with other proteins after secretion, preventing secretion through the dense cell wall structure of Gram-positive bacteria. Alternatively, proPC-PLC may interact with cytosolic chaperones, as shown for other bacterially secreted proteins (Lecker et al., 1989; Wattiau et al., 1996), in which case secretion through the bacterial membrane would also be regulated. The bacterial compartments in which proPC-PLC and Mpl are sorted during intracellular growth are being investigated. This information will be instrumental in determining the specific mechanisms regulating proPC-PLC activation during intracellular infection.

Successful spread of an infection relies largely on the ability of L. monocytogenes to remain intracellular and to escape rapidly from the vacuoles formed during cell–cell spread. PC-PLC is an important factor involved in vacuo-lar lysis during bacterial cell–cell spread. The results reported here indicate that vacuolar acidification triggers rapid Mpl-mediated activation and release of active PC-PLC, suggesting that PC-PLC acts within minutes of the formation of a secondary vacuole. Accordingly, Robbins et al. (1999) have recently shown by video microscopy that vacuoles formed upon bacterial cell–cell spread lyse within 5 min of their formation. The importance of this regulated release mechanism was further emphasized by the observation that premature release of active PC-PLC in the cytosol of mammalian cells is cytotoxic. Therefore, regulated release of PC-PLC is a mechanism that is essential to the pathogenicity of L. monocytogenes. There is a precedence for the regulated release of a protein in a Gram-positive bacterium. The β-d-fructosyltransferase of oral streptococci, which polymerizes fructose into extracellular fructans, is cell wall-associated and released from the bacterial cell only when its substrate is present in the medium (Milward and Jacques, 1990; Rathsam et al., 1993). The mechanism regulating release of this enzyme is also unknown. Future studies will elucidate what appears to be a novel mechanism regulating release of secreted proteins in Gram-positive bacteria and the importance of this regulation for the pathogenesis of L. monocytogenes.

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Wild-type L. monocytogenes strain 10403S (Portnoy et al., 1988) and isogenic deletion mutants DP-L1935 (ΔplcB) (Smith et al., 1995) and DP-L2296 (Δmpl) (Marquis et al., 1995) were used for this study. All strains were grown in brain heart infusion broth (BHI; Difco Laboratories) and were maintained on BHI agar. Stock cultures were stored at −808C.

Infection of J774 cells and metabolic labelling of PC-PLC

Infection of J774 cells and metabolic labelling were performed as previously described with some modifications (Marquis et al., 1997). For [35S]-methionine protein labelling, 106 J774 cells in 35 mm tissue culture dishes were infected with 4 – 8 × 106 bacteria grown overnight at 30°C, achieving an initial infection of approximately one or two bacteria per cell. At 30 min after infection, the cells were washed three times with PBS and gentamicin (10 μg ml−1) was added 1 h after infection. At 3.5 h after infection, cells were washed once with PBS and methionine-free DMEM supplemented with 10% dialysed FBS (Hyclone) and gentamicin was added. Cells were pulse labelled for the indicated period of time at 4 h after infection with 200 μl of the same medium, containing 90 μCi [35S]-methionine (Express [35S] protein labelling mix, NEN). Infected labelled cells were chased in medium supplemented with unlabelled methionine (2 mM) and chloramphenicol (20 μg ml−1) to prevent further incorporation of labelled methionine. The chasing medium is as specified in the figure legends. Host cell protein synthesis was not blocked at any time. Bacterial counts were determined in triplicate for each strain in each experiment as has been described previously (Portnoy et al., 1988).

pH modification of intracellular pH

The intracellular pH was modified using nigericin, a potassium ionophore that allows equilibration of pH across all membranes (Alpuche Aranda et al., 1992). Infected cells were perfused with a potassium buffer (133 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 15 mM Mes, 15 mM Hepes) adjusted to pH 7.3, pH 7.0, pH 6.5 or pH 6.0 and supplemented with nigericin (10 μM) for the indicated period of time. When used as chasing medium in a pulse chase experiment, the buffer was supplemented with cold methionine (2 mM) and chloramphenicol (20 μg ml−1).

For immunofluorescence microscopy, J774 cells were grown on 12 mm square coverslips and infected with bacteria grown overnight at 30°C, achieving an initial infection of approximately one bacterium per 5–10 cells. At 5.5 h after infection, infected cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 3.3% formaldehyde of EM grade (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in PBS. Alternatively, infected cells were washed with PBS, perfused for 5 min with potassium buffer pH 6.5 or pH 7.3 supplemented with nigericin (10 μM), washed again with PBS and fixed as described above. The samples were washed and processed for immunofluorescence staining as described below.

Immunoprecipitation of PC-PLC from infected J774 cells

Immunoprecipitation was performed as has been previously described (Marquis et al., 1997). Briefly, cell lysates and slurries of protein A Sepharose CL-4B beads (Sigma Chemical Co.) were prepared in RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1% NP-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Sigma Chemical Co.): 10 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 0.3 μM aprotinin, 1 μM leupeptin and 1 μM pepstatin. The affinity-purified antibody (20 μl per reaction) was preadsorbed with a lysate of uninfected unlabelled cells (2 × 106 J774 cells per reaction in 500 μl of RIPA buffer) for 1 h at 4°C. The lysate of infected labelled cells (106) was mixed with the adsorbed antibody for 1–1.5 h at 4°C, then with a slurry of protein A sepharose beads (10 mg per lysate) for 1 h at 4°C. Antigen–antibody complexes adsorbed on protein A sepharose beads were recovered by boiling in 2× SDS sample buffer, and resolved on a 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, the gel was processed for fluorography (En3hance, NEN). Equivalent numbers of bacteria were loaded per lane of an 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel.

Mutanolysin treatment of intracellular bacteria

J774 cells were grown on 12 mm square coverslips and infected with bacteria grown overnight at 30°C, achieving an initial infection of approximately one bacterium per 20–40 cells. At 4 h after infection, infected cells were washed with PBS and fixed in methanol/acetone (1:1 v/v) for 2 min. Fixed samples were washed with PBS and dried. The samples were rehydrated in PBS/0.1% saponin and reacted for 30 min at 37°C with or without mutanolysin (Sigma) at 10 units ml−1 in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.0. The samples were washed and processed for immunofluorescence staining as described below. For quantification analysis, a minimum of 100 bacteria distributed over 6–10 fields were counted per sample.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

The samples were blocked with 1% BSA in PBS/0.1% saponin and all of the antibodies were diluted in the same buffer. PC-PLC was detected by reacting the samples successively with affinity-purified rabbit anti-PC-PLC antibodies, donkey anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with biotin, and fluorescein streptavidin (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories). L. monocytogenes staining was performed last with a rabbit anti-L. monocytogenes antibody (Difco Laboratories) followed by rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Jackson Immunore-search Laboratories,). Between each reaction, the coverslips were extensively washed with PBS/saponin. The coverslips were mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) and sealed on glass slides. Alternatively, bacteria were detected by staining DNA with BisBenzimide (Hoechst 33258).

Immunofluorescence images were acquired using a Leica DMR XA microscope equipped with a CCD camera and controlled by the slidebook image processing software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations). Images were acquired in stacks of 0.5 μm, and deconvolved using the nearest-neighbour algorithm of slidebook. The exposure times and intensity settings were kept constant for all samples tested within an experiment.

Cytotoxicity assay and bright-field microscopy

J774 cells were grown on 12 mm square coverslips and infected with bacteria grown overnight at 30°C, achieving an initial infection of approximately one bacterium per 10–20 cells. At 5 h after infection, infected cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 3.3% formaldehyde of EM grade in PBS. Alternatively, infected cells were washed with PBS, perfused for 5 min with potassium buffer pH 6.5 supplemented with nigericin (10 μM), washed again with PBS and fixed as described above. Fixed cells were stained with Diff-Quick (Dade Diagnostics). The coverslips were mounted with Per-mount (Fisher Scientific).

Bright-field images were acquired using a Leica DMR XA microscope equipped with a CCD camera and controlled by theslidebook image processing software. Primary infected cells containing between 20 and 40 bacteria were analysed for signs of cytotoxicity after the nigericin treatment at pH 6.5. Cytotoxic effects were determined by a loss of cytosol density and of bacteria-containing protrusions, presumably as a result of plasma membrane lysis, accompanied in most cases by a condensation of the cell nucleus. One hundred infected cells were analysed per sample and the experiment was repeated four times. For each experiment, wild-type L. monocytogenes (strain 10403S) and isogenic mutants DPL1935 (ΔplcB) and DP-L2296 (Δmpl) were tested in parallel.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Anirban Banerjee from the Department of Surgery at UCHSC for the use of the immunofluorescence microscope and image analysis software. We are grateful to Daniel A. Portnoy for helpful comments and critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by US Public Health Services grant AI-42800 (to H. M.).

References

- Alberts B, Bray D, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Watson JD. Molecular Biology of the Cell. Garland Publishing; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Alpuche Aranda CM, Swanson JA, Loomis WP, Miller SI. Salmonella typhimurium activates virulence gene transcription within acidified macrophage phagosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10079–10083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilli A, Tilney LG, Portnoy DA. Dual roles of plcA in Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:143–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC Multistate outbreak of listeriosis – United States, 1998–99. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;281:317–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabiri GA, Sanger JM, Portnoy DA, Southwick FS. Listeria monocytogenes moves rapidly through the host–cell cytoplasm by inducing directional actin assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6068–6072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dramsi S, Leévi S, Triller A, Cossart P. Entry of Listeria monocytogenes into neurons occurs by cell-to-cell spread – an in vitro study. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4461–4468. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4461-4468.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber JM, Peterkin PI. Listeria monocytogenes, a food-borne pathogen. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:476–511. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.3.476-511.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag NE, Jacobs KE. Examination of Listeria monocytogenes intracellular gene expression by using the green fluorescent protein of Aequorea victoria. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1844–1852. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1844-1852.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geoffroy C, Raveneau J, Beretti J-L, Lecroisey A, Vazquez-Boland J-A, Alouf JE, Berche P. Purification and characterization of an extracellular 29-kilodalton phospholipase C from Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2382–2388. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2382-2388.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfine H, Johnston NC, Knob C. Nonspecific phospholipase C of Listeria monocytogenes: activity on phospholipids in Triton X-100-mixed micelles and in biological membranes. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4298–4306. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.14.4298-4306.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiffenberg L, Goebel W, Kim KS, Weiglein I, Bubert A, Engelbrecht F, et al. Interaction of Listeria monocytogenes with human brain microvascular endothelial cells: InlB-dependent invasion, long-term intracellular growth, and spread from macrophages to endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5260–5267. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5260-5267.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haäse CC, Finkelstein RA. Bacterial extracellular zinc-containing metalloproteases. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:823–837. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.4.823-837.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecker S, Lill R, Ziegelhoffer T, Georgopoulos C, Bassford PJ, Jr, Kumamoto CA, Wickner W. Three pure chaperone proteins of Escherichia coli – SecB, trigger factor, and GroEL – form soluble complexes with precursor proteins in vitro. EMBO J. 1989;8:2703–2709. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08411.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquis H, Doshi V, Portnoy DA. The broad-range phospholipase C and a metalloprotease mediate listeriolysin O-independent escape of Listeria monocytogenes from a primary vacuole in human epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4531–4534. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4531-4534.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquis H, Goldfine H, Portnoy DA. Proteolytic pathways of activation and degradation of a bacterial phospholipase C during intracellular infection by Listeria monocytogenes. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1381–1392. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengaud J, Geoffroy C, Cossart P. Identification of a new operon involved in Listeria monocytogenes virulence: its first gene encodes a protein homologous to bacterial metalloproteases. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1043–1049. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.3.1043-1049.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milward CP, Jacques NA. Secretion of fructosyltransferase by Streptococcus salivarius involves the sucrose-dependent release of the cell-bound form. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:165–169. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-1-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moors MA, Levitt B, Youngman P, Portnoy DA. Expression of listeriolysin O and ActA by intracellular and extracellular Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1999;67:131–139. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.131-139.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounier J, Ryter A, Coquis-Rondon M, Sansonetti PJ. Intracellular and cell-to-cell spread of Listeria monocytogenes involves interaction with F-actin in the enterocyte-like cell line Caco-2. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1048–1058. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.1048-1058.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarre WW, Schneewind O. Surface proteins of gram-positive bacteria and mechanisms of their targeting to the cell wall envelope. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:174–229. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.174-229.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niebuhr K, Chakraborty T, Koöllner P, Wehland J. Production of monoclonal antibodies to the phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C of Listeria monocytogenes, a virulence factor for this species. Med Microbiol Lett. 1993;2:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Portnoy DA, Jacks PS, Hinrichs DJ. Role of hemolysin for the intracellular growth of Listeria monocyto-genes. J Exp Med. 1988;167:1459–1471. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.4.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poyart C, Abachin E, Razafimanantsoa I, Berche P. The zinc metalloprotease of Listeria monocytogenes is required for maturation of phosphatidylcholine phospholipase C: direct evidence obtained by gene complementation. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1576–1580. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1576-1580.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathsam C, Giffard PM, Jacques NA. The cell-bound fructosyltransferase of Streptococcus salivarius: the carboxyl terminus specifies attachment in a Streptococcus gordonii model system. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4520–4527. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.14.4520-4527.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raveneau J, Geoffroy C, Beretti J-L, Gaillard J-L, Alouf JE, Berche P. Reduced virulence of a Listeria monocytogenes phospholipase-deficient mutant obtained by transposon insertion into the zinc metalloprotease gene. Infect Immun. 1992;60:916–921. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.916-921.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins JR, Barth AI, Marquis H, de Hostos EL, Nelson WJ, Theriot JA. Listeria monocytogenes exploits normal host cell processes to spread from cell to cell. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:1333–1349. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.6.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlech WF., III Listeria gastroenteritis – old syndrome, new pathogen. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:130–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701093360211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlüter D, Domann E, Buck C, Hain T, Hof H, Chakraborty T, Deckert-Schlüter M. Phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C from Listeria monocytogenes is an important virulence factor in murine cerebral listeriosis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5930–5938. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5930-5938.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneewind O, Model P, Fischetti VA. Sorting of protein A to the staphylococcal cell wall. Cell. 1992;70:267–281. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90101-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GA, Marquis H, Jones S, Johnston NC, Portnoy DA, Goldfine H. The two distinct phospholipases C of Listeria monocytogenes have overlapping roles in escape from a vacuole and cell-to-cell spread. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4231–4237. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4231-4237.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theriot JA, Mitchison TJ, Tilney LG, Portnoy DA. The rate of actin-based motility of intracellular Listeria monocytogenes equals the rate of actin polymerization. Nature. 1992;357:257–260. doi: 10.1038/357257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilney LG, Portnoy DA. Actin filaments and the growth, movement, and spread of the intracellular bacterial parasite, Listeria monocytogenes. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:1597–1608. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.4.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wart HE, Birkedal-Hansen H. The cysteine switch: a principle of regulation of metalloproteinase activity with potential applicability to the entire matrix metalloproteinase gene family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5578–5582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.14.5578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Boland J-A, Kocks C, Dramsi S, Ohayon H, Geoffroy C, Mengaud J, Cossart P. Nucleotide sequence of the lecithinase operon of Listeria monocytogenes and possible role of lecithinase in cell-to-cell spread. Infect Immun. 1992;60:219–230. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.1.219-230.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wattiau P, Woestyn S, Cornelis GR. Customized secretion chaperones in pathogenic bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:255–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckert WR, Marquis H, Goldfine H. Modulation of enzymatic activity and biological function of Listeria monocytogenes broad-range phospholipase C by amino acid substitutions and by replacement with the Bacillus cereus ortholog. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4823–4831. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4823-4831.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]