Abstract

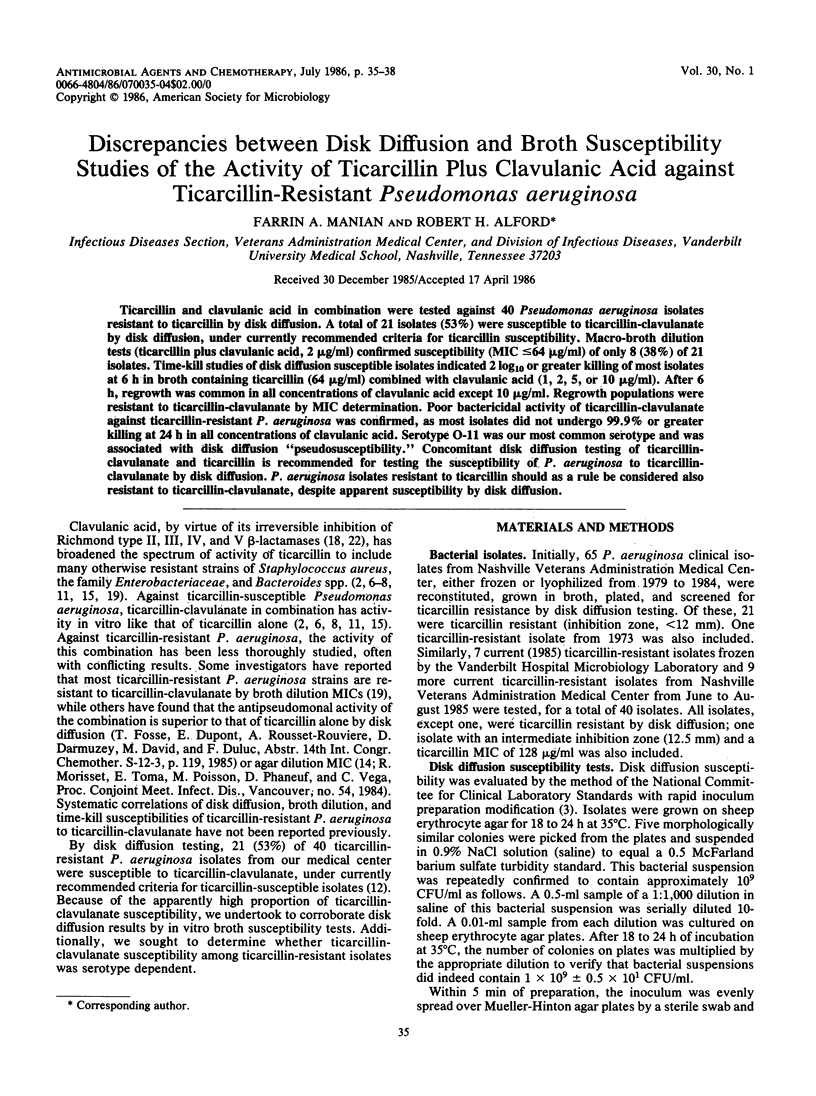

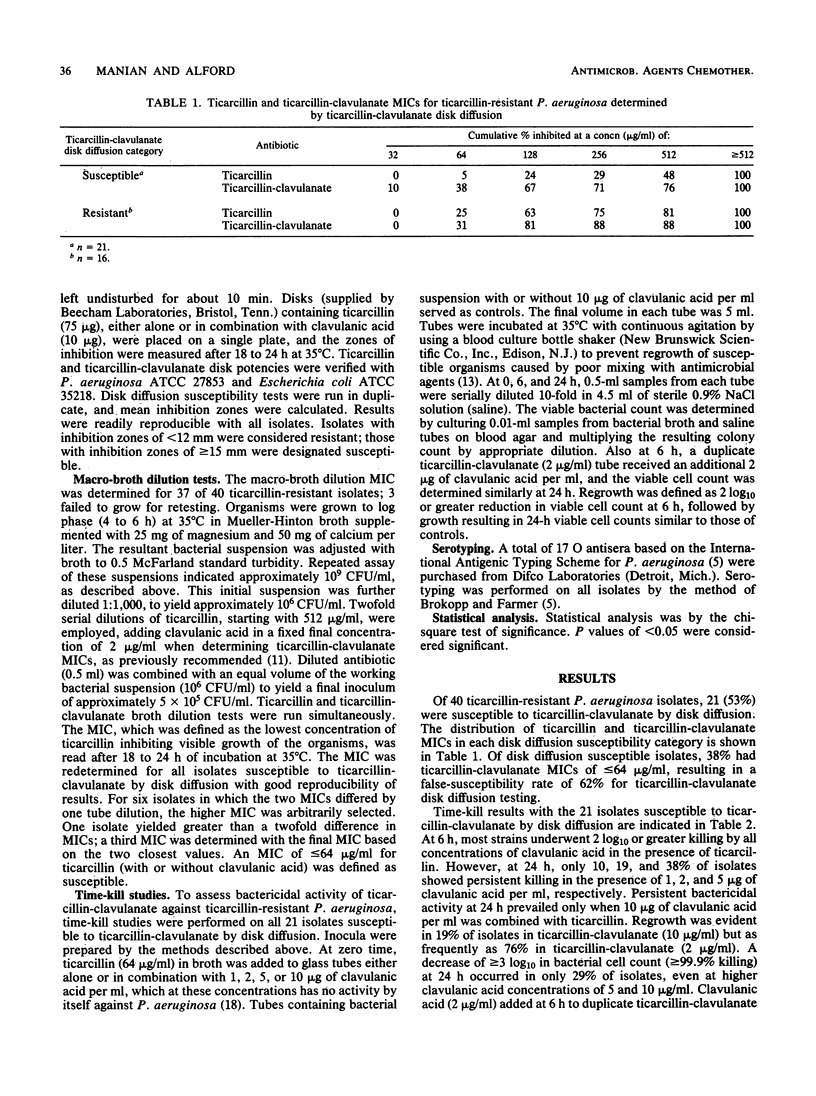

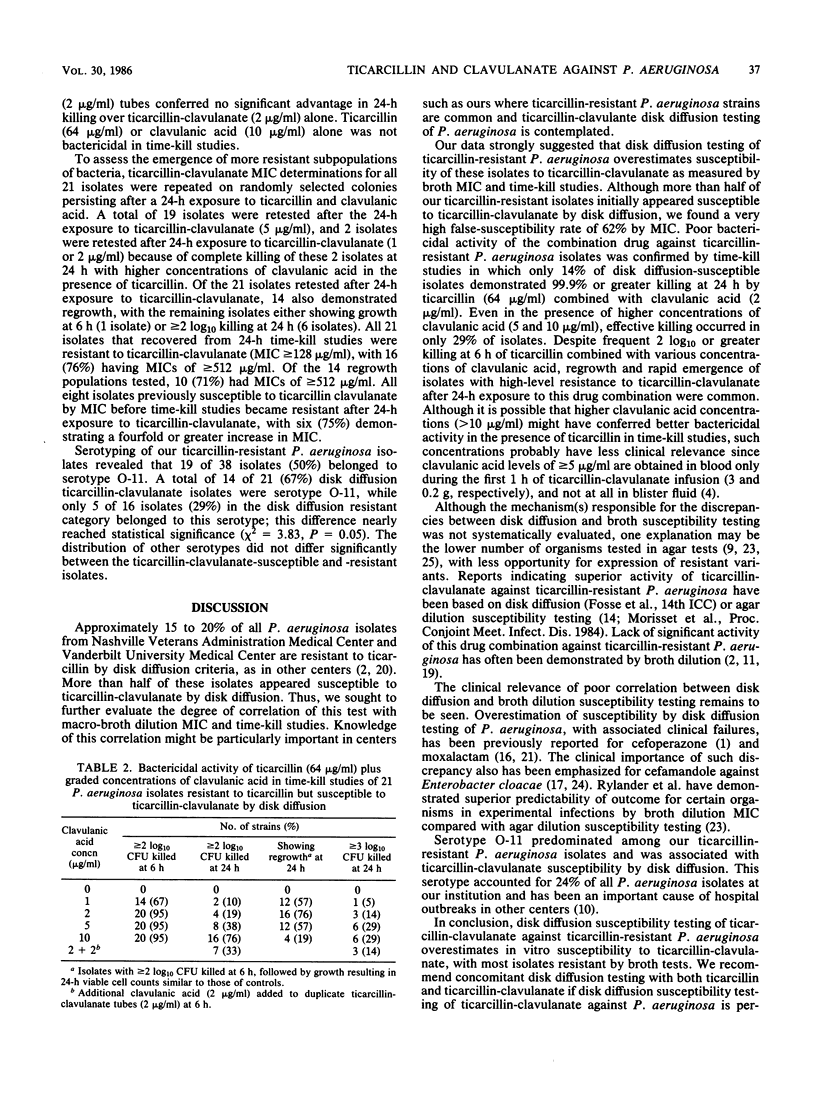

Ticarcillin and clavulanic acid in combination were tested against 40 Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates resistant to ticarcillin by disk diffusion. A total of 21 isolates (53%) were susceptible to ticarcillin-clavulanate by disk diffusion, under currently recommended criteria for ticarcillin susceptibility. Macro-broth dilution tests (ticarcillin plus clavulanic acid, 2 micrograms/ml) confirmed susceptibility (MIC less than or equal to 64 micrograms/ml) of only 8 (38%) of 21 isolates. Time-kill studies of disk diffusion susceptible isolates indicated 2 log10 or greater killing of most isolates at 6 h in broth containing ticarcillin (64 micrograms/ml) combined with clavulanic acid (1, 2, 5, or 10 micrograms/ml). After 6 h, regrowth was common in all concentrations of clavulanic acid except 10 micrograms/ml. Regrowth populations were resistant to ticarcillin-clavulanate by MIC determination. Poor bactericidal activity of ticarcillin-clavulanate against ticarcillin-resistant P. aeruginosa was confirmed, as most isolates did not undergo 99.9% or greater killing at 24 h in all concentrations of clavulanic acid. Serotype O-11 was our most common serotype and was associated with disk diffusion "pseudosusceptibility." Concomitant disk diffusion testing of ticarcillin-clavulanate and ticarcillin is recommended for testing the susceptibility of P. aeruginosa to ticarcillin-clavulanate by disk diffusion. P. aeruginosa isolates resistant to ticarcillin should as a rule be considered also resistant to ticarcillin-clavulanate, despite apparent susceptibility by disk diffusion.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bailey R. R., Peddie B., Blake E., Bishop V., Reddy J. Cefoperazone in the treatment of severe or complicated infections. Drugs. 1981;22 (Suppl 1):76–86. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198100221-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry A. L., Ayers L. W., Gavan T. L., Gerlach E. H., Jones R. N. In vitro activity of ticarcillin plus clavulanic acid against bacteria isolated in three centers. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1984 Jun;3(3):203–206. doi: 10.1007/BF02014879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S., Wise R., Weston D., Dent J. Pharmacokinetics and tissue penetration of ticarcillin combined with clavulanic acid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983 Jun;23(6):831–834. doi: 10.1128/aac.23.6.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey P., Glauser M. Susceptibility of gram-negative bacteria and Staphylococcus aureus to combinations of ticarcillin and clavulanic acid. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1983 Dec;2(6):541–547. doi: 10.1007/BF02016562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay B., Hall I. In vitro activity of ticarcillin plus clavulanic acid (BRL 28500, 'Timentin') against ticarcillin-resistant gram-negative rods. Curr Med Res Opin. 1984;9(3):157–160. doi: 10.1185/03007998409109575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke A. M., Zemcov S. J. Clavulanic acid in combination with ticarcillin: an in-vitro comparison with other beta-lactams. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1984 Feb;13(2):121–128. doi: 10.1093/jac/13.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson H. M., Sherris J. C. Antibiotic sensitivity testing. Report of an international collaborative study. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand B Microbiol Immunol. 1971;217(Suppl):1+–1+. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer J. J., 3rd, Weinstein R. A., Zierdt C. H., Brokopp C. D. Hospital outbreaks caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: importance of serogroup O11. J Clin Microbiol. 1982 Aug;16(2):266–270. doi: 10.1128/jcm.16.2.266-270.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs P. C., Barry A. L., Thornsberry C., Jones R. N. In vitro activity of ticarcillin plus clavulanic acid against 632 clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984 Mar;25(3):392–394. doi: 10.1128/aac.25.3.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs P. C., Jones R. N., Barry A. L., Thornsberry C. Disk diffusion susceptibility testing of ticarcillin plus clavulanic acid. J Clin Microbiol. 1984 Apr;19(4):555–557. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.4.555-557.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwynn M. N., Webb T. L., Rolinson G. N. Regrowth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other bacteria after the bactericidal action of carbenicillin and other beta-lactam antibiotics. J Infect Dis. 1981 Sep;144(3):263–269. doi: 10.1093/infdis/144.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry D., Skidmore A. G., Ngui-Yen J., Smith A., Smith J. A. In vitro activities of enoxacin, ticarcillin plus clavulanic acid, aztreonam, piperacillin, and imipenem and comparison with commonly used antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985 Aug;28(2):259–264. doi: 10.1128/aac.28.2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter P. A., Coleman K., Fisher J., Taylor D. In vitro synergistic properties of clavulanic acid, with ampicillin, amoxycillin and ticarcillin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1980 Jul;6(4):455–470. doi: 10.1093/jac/6.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathisen G. E., Meyer R. D., Thompson J. M., Finegold S. M. Clinical evaluation of moxalactam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982 May;21(5):780–786. doi: 10.1128/aac.21.5.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray P. R., Granich G. G., Krogstad D. J., Niles A. C. In vivo selection of resistance to multiple cephalosporins by enterobacter cloacae. J Infect Dis. 1983 Mar;147(3):590–590. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.3.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neu H. C., Fu K. P. Clavulanic acid, a novel inhibitor of beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1978 Nov;14(5):650–655. doi: 10.1128/aac.14.5.650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paisley J. W., Washington J. A., 2nd Combined activitiy of clavulanic acid and ticarcillin against ticarcillin-resistant, gram-negative bacilli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1978 Aug;14(2):224–227. doi: 10.1128/aac.14.2.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry M. G., Neu H. C. Ticarcillin for treatment of serious infections with gram-negative bacteria. J Infect Dis. 1976 Nov;134(5):476–485. doi: 10.1093/infdis/134.5.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preheim L. C., Penn R. G., Sanders C. C., Goering R. V., Giger D. K. Emergence of resistance to beta-lactam and aminoglycoside antibiotics during moxalactam therapy of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982 Dec;22(6):1037–1041. doi: 10.1128/aac.22.6.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reading C., Cole M. Clavulanic acid: a beta-lactamase-inhiting beta-lactam from Streptomyces clavuligerus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1977 May;11(5):852–857. doi: 10.1128/aac.11.5.852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rylander M., Brorson J. E., Johnsson J., Norrby R. Comparison between agar and broth minimum inhibitory concentrations of cefamandole, Cefoxitin, and cefuroxime. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979 Apr;15(4):572–579. doi: 10.1128/aac.15.4.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders C. C., Moellering R. C., Jr, Martin R. R., Perkins R. L., Strike D. G., Gootz T. D., Sanders W. E., Jr Resistance to cefamandole: a collaborative study of emerging clinical problems. J Infect Dis. 1982 Jan;145(1):118–125. doi: 10.1093/infdis/145.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton C. W. Susceptibility testing revisited. Prog Clin Pathol. 1984;9:65–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]