Abstract

The molecular mechanisms underlying the generation of the various types of cells in the vertebrate retina are largely unknown. We investigated the possibility that genes belonging to the basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) family of transcriptional factors participate in cell-type specification during retinal neurogenesis. Chick neuroD was isolated from an embryonic cDNA library and its deduced amino acid sequence showed 75% identity with mouse neuroD. In situ hybridization showed that neuroD was expressed in cells located at the outer portion of the developing retinal neuroepithelium, the location where prospective photoreceptors reside. Misexpression of neuroD in retinal neuroepithelium through replication-competent, transformation-deficient retroviruses produced a retina with three, instead of two, layers of photoreceptor cells; the number of cells that express visinin, a marker for cone photoreceptors, increased over 50% compared to control embryos misexpressing the green fluorescent protein. No significant changes were observed in the number of other retinal neurons, including those that express RA4 (ganglion cells), pax6 (ganglion cells and amacrine cells), and chx10 (bipolar cells). Retroviral-driven misexpression of neuroD in monolayer cultures of retinal pigment epithelium yielded de novo production of photoreceptor cells with no other types of retinal neurons detected. We propose that neuroD is important for photoreceptor cell production in the vertebrate retina.

Keywords: photoreceptors, neuroD, transdifferentiation, RPE

The vertebrate retina is a stratified structure of three nuclear layers: the ganglion cell layer (GCL), the inner nuclear layer (INL), and the outer nuclear layer (ONL), separated by two synaptic layers. Residing in these layers are cells that differ functionally and morphologically. Photoreceptors, whose perikarya constitute the ONL, are a group of specialized sensory neurons. Photoreceptor cell degeneration is the basis of several forms of vision loss in humans, including age-related macular degeneration (Allikmets et al., 1997a,b; Sun and Nathans, 1997). Presently, it remains elusive how during retinal neurogenesis photoreceptor precursors are selected from those that differentiate into other cell types, such as ganglion cells, horizontal cells, amacrine cells, bipolar cells, and retinal glia. Various studies which used lineage analysis (Turner and Cepko, 1987) and selective cell killing (Raymond, 1991; Reh, 1991) have suggested that lineage may not be a deterministic factor and that microenviron-mental cues to which multipotent progenitors are exposed play an important role in generating the variety of retinal cells. The notion that retinal lineage is not deterministic, however, has been challenged by experimental observations which showed that the retinal neuroepithelial cells in different developmental stages may be intrinsically different from one another (Reh, 1991), and that some retinal cells clearly demonstrate lineage bias (Huang and Moody, 1997; Alexiades and Cepko, 1997). A recently identified homeobox gene, crx, has been shown to be predominantly expressed in the photoreceptor cells of embryonic and adult retina (Furukawa et al., 1997; Chen et al., 1997). Its protein binds and transactivates photoreceptor cell-specific genes including rhodopsin and interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein (Furukawa et al., 1997; Chen et al., 1997). Functional analysis has shown that crx is required for the formation and maintenance of the outer segment and yet is not sufficient to instruct photoreceptor cell fate (Furukawa et al., 1997). This suggests that while it is necessary for photoreceptor cell differentiation and cytoarchitecture maintenance, crx may not be a determining factor for photoreceptors.

neuroD, which encodes a transcriptional factor belonging to the basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) family, has been demonstrated to act as a neuronal determination and/or differentiation gene (Lee et al., 1995). Its mRNA is capable of inducing premature differentiation of neuronal precursors when microinjected into Xenopus embryos. The injected mRNA can also ectopically produce neurons from presumptive ectodermal cells (Lee et al., 1995). Based on its transient and restricted expression, Lee et al. (1995) proposed that neuroD might be required for the production of certain types of neurons; but which types are unknown. Mice lacking neuroD were reported to have a normally developed nervous system despite its abundant expression in the nervous system during normal development (Naya et al., 1997). This is likely due to compensation by other bHLH genes belonging to the neuroD subfamily (Schwab et al., 1998). Cell-specific transcriptional activity of neuroD has recently been demonstrated by Poulin et al. (1997). We isolated chick neuroD from an embryonic brain, examined the expression of neuroD in developing chick retina, and studied its involvement in retinal cell production under in vivo and in vitro conditions. Here, we report that neuroD contributes to the production of photoreceptor cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning of the Chick neuroD Gene

Based on the published sequence (Lee et al., 1995), we isolated the entire coding region of mouse neuroD by reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from first-strand cDNA of embryonic day 14 (E14) mouse brain. The mouse neuroD fragment was verified by sequencing and used as probes to isolate chick neuroD from an E8 brain cDNA library (Yan and Wang, 1998). Six cDNA clones were analyzed, and they contained inserts ranging from 2.0 to 2.6 kilobases (kb). The variations in length appeared to result from cDNA synthesis, since they covered different portions of the coding or 5′-noncoding sequence, while sharing a 1.4-kb 3′-noncoding region. Two were full-length clones containing 5′-noncoding sequences of 74 base pairs (bp) and 185 bp, respectively. The nucleotide sequence was determined from both strands at the Core Sequence Facility of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

In Situ Hybridization

In situ mRNA hybridization on cryosections (8 μm) of retinal tissues was performed essentially as previously described (Wang and Adler, 1994) with the following modifications: A proteinase K digestion was included during pretreatment and a final stringent wash was done at 70°C with 0.1× SSC for 1 h. Without the latter modification, false-positive signals were abundant. Digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes against neuroD were 450 bp in length and represented the middle of the coding sequence. The RNA probe against chick visinin covered the entire coding region (580 bp), which was PCR amplified based on published sequence information (Yamagata et al., 1990) from a first-strand cDNA pool from E18 retinas. The anti-chx10 RNA probe was 600 bp from the 3′-untranslated sequence (Belecky-Adams et al., 1997). The anti-pax6 RNA probe covered a 560-bp sequence at the 3′ end of the cloned fragment (Li et al., 1994). The DNA fragments used to make the chx10 and pax6 probes were amplified from a first-strand cDNA pool from E8–10 retinas.

Retinal Cell Culture

For comparison of the endogenous expression of neuroD and visinin, E7 retinas were dissected free from other ocular tissues, and the cells were dissociated with trypsin digestion. After passing the cell suspension through a cell strainer with a 35-μM pore size, cells (1–2 × 106) were seeded onto a polyornithine-treated 35-mm dish and cultured for 24 h with medium 199 plus 10% fetal calf serum in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and processed for either in situ hybridization or immunocytochemistry with monoclonal antibodies against Islet-1 (Yamada et al., 1993) obtained from the Developmental Studies of Hybridoma Bank at the University of Iowa.

To quantitate the cell populations in retinas transduced with retroviruses, we disassociated E9 retina cells in the same manner as above, but seeded at lower density to facilitate counting. Retinal tissues were dissected and pooled from the right eyes of six embryos injected with retroviruses expressing either neuroD or GFP as a control. Disassociated retinal cells were seeded on a number of 35-mm dishes and allowed to attach to polyornithinetreated dishes for 4 hat 37°C before fixation for immunocytochemical or in situ hybridization analysis. Six dishes were used for each label/marker: RA4 (a generous gift from S. McLoon) for ganglion cells (Waid and McLoon, 1995); visinin for photoreceptor cells (Yamagata et al., 1990); and chx10 for bipolar cells and pax6 for amacrine cells (Belecky-Adams et al., 1997). Student's t test was used to calculate the p value, and p < .05 was considered to be significant.

Generation of Viruses Expressing neuroD or the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP)

The coding region of GFP was enzyme digested out of plasmid pRCGFP-C1 (Clontech, Palo Alta, CA), inserted into Cla12Nco shuttle vector (Hughes et al., 1987) at the NcoI site, and subcloned into provirus RCAS (B/P) at the ClaI site. The coding region of mouse neuroD was cloned into the provirus in a similar manner. To generate retroviruses expressing chick neuroD, a SmaI–BglII fragment, which covers the entire coding region plus 179 bp of 5′-untranslated sequence and 87 bp of 3′-untranslated sequence, was first inserted into the shuttle vector at the XbaI site. A ClaI cassette was then digested out of the shuttle vector and inserted into RCAS (B/P). After transfection of the recombinant provirus into chicken embryonic fibroblast cells, retrovirus particles which were replication competent and transformation deficient were harvested from the medium and concentrated as described (Fekete and Cepko, 1993), except that cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 5000 × g for 10 min. The titer of the virus stock was usually between 5 × 107 and 1 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL. The synthesis of GFP was verified by immunocytochemistry with anti-GFP antibody from Clontech (data not shown).

Microinjection of Retroviruses

Fertilized, pathogen-free chicken (White Leghorn) eggs were purchased from Spafas (Preston, CT), incubated, and used throughout the study. Concentrated virus, in medium 199, was microinjected at a site ventral to the optic cup [see Fig. 3(A)] into the neural tube, from which the injected fluid could fill the “subretinal” space of the optic cup. The flow of injected viral suspension into the subretinal space was visualized by inclusion of Fast green (Fekete and Cepko, 1993). Microinjections were carried out through a micromanipulated micropipette attached to a pneumatic pump with a positive pressure delivery system. The first injection was performed when the embryo was between stage 14 and 15 (Hamburger and Hamilton, 1951), and two subsequent injections were given at 3-h intervals. We routinely checked the infection by immunocytochemistry with specific antibodies against a viral protein P27 (Spafas).

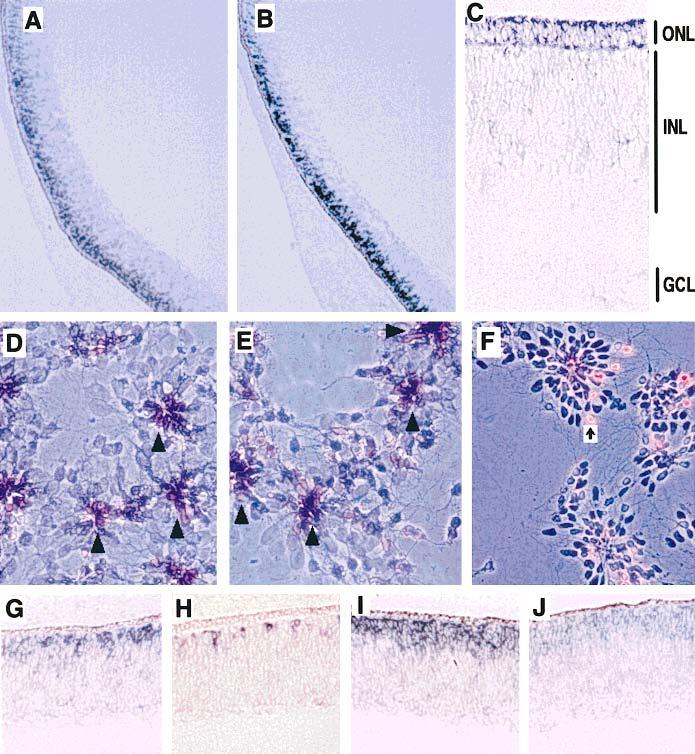

Figure 3.

Misexpression of neuroD in the retinal neuroepithelium produced a neural retina with a thickened ONL. Concentrated virus expressing neuroD or GFP was microinjected into the neurotube at a site ventral to the optic cup [arrow in (A)] at E2, and the neural retina harvested for histological analysis at E8.5. Although the virus can spread innocuously throughout a population of dividing cells, we found that a single injection often resulted in partial infection of the retina (B) when assayed with specific antiviral P27 antibodies, and a thorough infection (C) could be reliably obtained with repeated injections. The ONL in embryos microinjected with viruses expressing GFP, like that in normal chick embryos not subjected to microinjection, is composed of two layers of cells (D). Embryos microinjected with viruses expressing neuroD have neural retinas having an ONL with three layers of photoreceptor cells (E). Shown (D,E) are comparable, inferior regions on sagittal sections of E8.5 retinas stained with Hoechst 33342. Magnifications: (B,C) ×150; (D,E) ×1100.

Cell Cultures of Retinal Pigment Epithelium (RPE)

E6 or E8 RPE was isolated in the following manner. Eyes were enucleated and mesenchyme outside the RPE was removed. A circular incision was made posterior to the ciliary epithelium to remove the anterior portion, including the lens, ciliary epithelium and pigment epithelium, and associated retina tissue. The RPE was then readily separated from the retina. For each experiment, RPE from 26 E6 eyes were collected, trypsinized and seeded onto 78 dishes (35 mm in diameter), and the cells were cultured in medium 199 plus 10% fetal calf serum at 37°C under 5% CO2. The medium was changed every other day. After 3 days, when the culture became 50–70% confluent, 2 μL of concentrated viral stock (retroviruses expressing either GFP or neuroD) was added to each 35-mm dish. A set of dishes was taken out at various time points and processed for immunocytochemical or in situ analysis to assess the number of cells positive for various retinal cell markers. Labels for immunocytochemical analysis included HNK-1/N-CAM (clone VC1.1; Sigma), RA4, and monoclonal antibodies against a microtubule-associated protein, MAP2 (a, b, and c; clone HM-1; Sigma). Probes for in situ hybridization included digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA to visinin, chx10, and pax6. Three dishes were used for each label at a single time point and data were collected from at least three independent experiments. Viral infection of the culture was monitored using anti-P27 antibody, and > 70% infection was achieved on day 4.

RESULTS

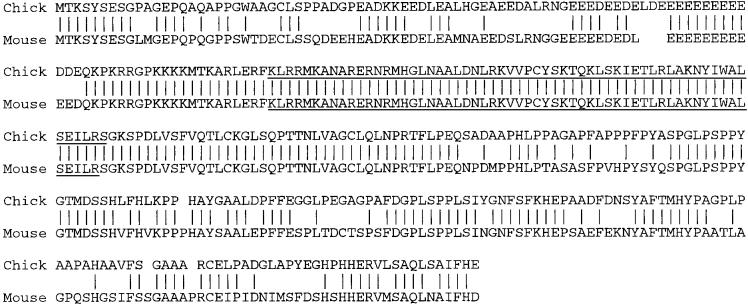

Deduced Amino Acid Sequence of Chick neuroD

Chick neuroD was isolated from a cDNA library of E8 brain. Its deduced amino acid sequence shares 75% identity with mouse NeuroD (Fig. 1). The bHLH region and regions adjacent to it are 100% identical to mouse NeuroD. This high degree of sequence identity suggests that the isolated gene is the true chick ortholog of neuroD.

Figure 1.

The deduced amino acid sequence of chick neuroD. Chick neuroD is highly homologous to mouse neuroD (Lee et al., 1995) at the amino acid level, with an overall identity of 75%. The bHLH regions (underlined) show 100% identity between the two sequences. Vertical lines indicate identical residues. Gaps were introduced to maximize homology. The GenBank accession number for chick neuroD is AF060885.

Expression of neuroD in the Developing Chick Retina

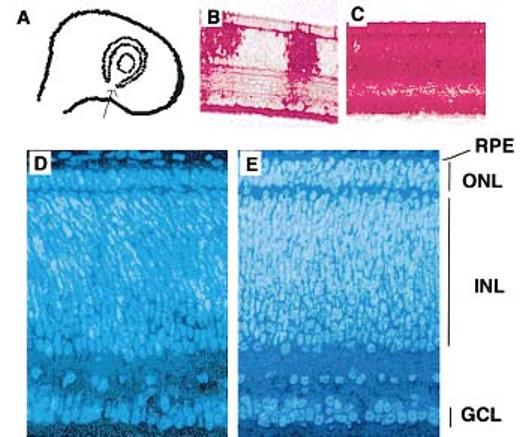

In situ hybridization with a very high stringency wash (see Methods) revealed that cells expressing neuroD were mostly confined to the outer portion of the E7 retinal neuroepithelium [Fig. 2(A)]. This location closely matches the expression of visinin [Fig. 2(B)], a gene encoding a calcium-binding protein in cone cells (Yamagata et al., 1990), which are the predominant photoreceptor cell type in the chick retina (Morris and Shorey, 1967). This suggests that neuroD may be expressed in young photoreceptors or their precursor cells.

Figure 2.

Expression pattern of neuroD in developing chick retina (bright field) and in disassociated retinal cells (phase contrast) examined using in situ hybridization. neuroD expression was detected in the outer portion of E7 retinal neuroepithelium (A). The expression of visinin, a specific marker for photoreceptor cells, was also detected at the same spatial location (B). By E9, neuroD expression was weakly detected in the ONL (C). In cultures of disassociated retinal cells, both neuroD mRNA (D) and visinin mRNA (E) were detected in cells at the center of the rosettes (arrowheads). Purple indicates positive signals, while background cells appeared light blue under phase contrast. Islet-1 immunopositive cells [arrow in (F)], which were mainly ganglion cells (Austin et al., 1995), were excluded from the center of the rosettes. At E5, expression of neuroD was substantial (G), while that of visinin was minimal (H). A down-regulation of neuroD expression appeared as cells established their identities, since fewer mRNA were detected at the fundus (J) where development is more advanced than the peripheral region (I) of an E7 retina. Magnifications: (A,B) ×25; (C–F) 100; (G,H) ×150.

However, an E7 retina is not a stratified structure and includes both proliferating and differentiating cells; other retinal cells may also be found at the outer portion of the retinal epithelium at this stage of development. Therefore, the distribution of cells expressing neuroD was examined in older retinas with stratified nuclear layers. At E9, some cells still expressed neuroD, although expression at this stage was weak, and the expressing cells were confined to the newly formed ONL, which is composed of photoreceptor cells [Fig. 2(C)]. Cells in the INL and GCL appeared to be negative for neuroD expression.

The expression of neuroD was also compared with that of visinin in retinal cell cultures, taking advantage of the fact that under middle- to high-density culturing conditions, retinal cells aggregate into rosettes with young photoreceptor cells typically at the center (Kelley et al., 1994). Indeed, as with visinin [Fig. 2(E)], the expression of neuroD was detected in cells primarily located at the center of the rosettes [Fig. 2(D)], while Islet-1 immuno-positive cells (ganglion cells) were found to be scattered around [Fig. 2(F)].

High levels of neuroD expression were evident in retinas at E5 [Fig. 2(G)], when only a few cells were positive for visinin mRNA [Fig. 2(H)]. The expression of neuroD remained high up to E7, when a decrease was observed at the fundus region [Fig. 2(J)], where development is more advanced than peripheral regions [Fig. 2(I)]. At E9, a low level of neuroD mRNA was detected in cells of the newly formed ONL [Fig. 2(C)] and no signals were obtained in retinas older than E10.

Misexpression of neuroD in Retinal Neuroepithelium

The apparent concurrence of neuroD expression with the genesis of photoreceptor cells in the developing chick retina prompted an investigation of the participation of neuroD in photoreceptor cell production. A replication-competent, transformation-deficient retrovirus, RCAS (B/P) (Hughes et al., 1987), was used to misexpress neuroD in retinal neuroepithelium [Fig. 3(A)]. RCAS (B/P) expressing GFP was used as a control. Expression of GFP in transduced chick cells was confirmed by immunocytochemistry using specific anti-GFP antibodies (data not shown). The retroviral suspension was delivered into the optic cup through microinjection [Fig. 3(A)]. Although a single injection at stage 14–17 has been reported to produce extensive infection of the retina (Fekete and Cepko, 1993), we found that a near-complete infection [Fig. 3(C)] was reproducibly achieved if the initial injection was carried out at stage 14–15 with two subsequent injections at 3-h intervals.

Viral-driven neuroD misexpression in the retinal neuroepithelium increased the number of cells expressing visinin throughout retinal neurogenesis (see below; data not shown). At E8.5, the photoreceptor cell layer (i.e., ONL) became conspicuous except at the very periphery. The ONL of retinas from embryos not subjected to microinjection (normal embryos) or from embryos injected with retroviruses expressing GFP (n = 8 embryos) was composed of two layers of photoreceptor nuclei or cells [Fig. 3(D)]. However, in embryos injected with viruses expressing chick neuroD (n = 4 embryos) it was composed of three layers of cells [Fig. 3(E)]. The mouse neuroD gene was equally powerful in producing a thickened ONL with an extra layer of cells when misexpressed in the chick retinal neuroepithelium in the same manner (n = 4 embryos; data not shown). No significant changes were observed in the thickness of the INL or GCL [Fig. 3(E) vs. (D)].

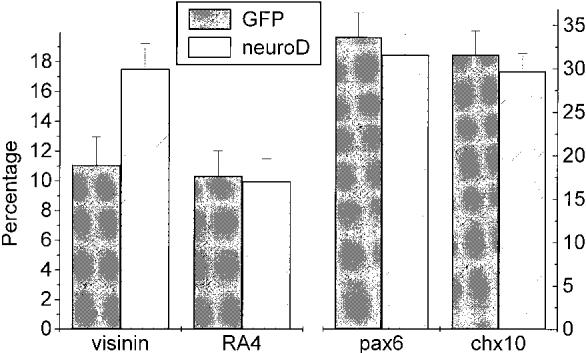

Disassociated cells from E9 retinas were analyzed to quantify the population change as a result of misexpression of neuroD. Cells expressing visinin accounted for 11.1 ± 1.85% of the total cells in embryos misexpressing GFP (n = 6), and 17.5 ± 1.71% in embryos misexpressing neuroD (n = 6; p = .0001) (Fig. 4). This represents an increase of 57.7% in the number of cells expressing visinin and is consistent with the histological observation of an extra layer of cells in the ONL. The number of ganglion cells, which were labeled by RA4 (Waid and McLoon, 1995), did not show a significant change (9.96 ± 1.52% vs. 10.32 ± 1.69%;p = .699) (Fig. 4 . There appeared to be very slight reductions in two major subpopulations of INL cells: those expressing pax6 (amacrine cells; Belecky-Adams et al., 1997) dropped from 33.6 ± 2.8% in the embryos misexpressing GFP to 31.6 ± 2.4% in embryos mis-expressing neuroD; cells expressing chx10 (bipolar cells; Belecky-Adams et al., 1997) dropped from 31.6 ± 2.7% to 29.7 ± 2.1%. However, the reductions were not statistically significant (p = .208 and p = .212, respectively) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison of major retinal cell types in embryos misexpressing either neuroD or GFP. The percentage of cells expressing visinin increased from 11.1% in embryos (n = 6) misexpressing GFP to 17.5% in embryos (n = 6) misexpressing neuroD (p.0001). There were no significant changes (p = .699) in the number of RA4-positive ganglion cells. There seemed a very slight, statistically insignificant reduction in the number of cells expressing pax6 (p = .208) or chx10 (p = .212) in embryos misexpressing neuroD compared with that in the embryos misexpressing GFP. The number of positive cells is shown as the mean (±S. D.) obtained from six dishes (per marker), each with countedmore than 1300 cells counted.

De Novo Photoreceptor Cell Production from RPE Cell Cultures

The hypothesis that neuroD plays an important role in photoreceptor cell production was further tested in vitro with cultured RPE cells, taking advantage of the fact that these cells can undergo transdifferentiation with proper stimulation (Zhao et al., 1997). We reasoned that if neuroD was capable of producing extra photoreceptor cells when misexpressed in the retina, it might induce de novo generation of photoreceptor cells from cultured RPE cells. Monolayer cultures of RPE cells were infected at 50–70% confluence with retroviruses expressing neuroD or GFP. Infection was monitored by anti-P27 immunocytochemistry, which showed that 4 days after the inoculation with viruses (day 4), more than 70% of the cells had become positive for the viral protein.

Change in gene expression as a result of expression of neuroD was initially monitored with antibodies against HNK-1/N-CAM, an early marker for many neuronal cell types (Nordlander, 1989) and a marker for RPE transdifferentiation (Zhao et al., 1997). At day 4 after infection, cells in cultures infected with retrovirus expressing GFP remained negative [Fig. 5(A)]; however, when infected with viruses expressing neuroD, a large number of cells became positive [Fig. 5(B)]. At day 2 after infection, very few cells were positive for HNK-1/N-CAM. The morphology of most cells positive for HNK-1/N-CAM in younger cultures (such as at day 4) appeared to be nonneuronal—large and flat [Fig. 5(B)]. In older cultures, however, more cells became neuron-like with compact cell bodies and small processes.

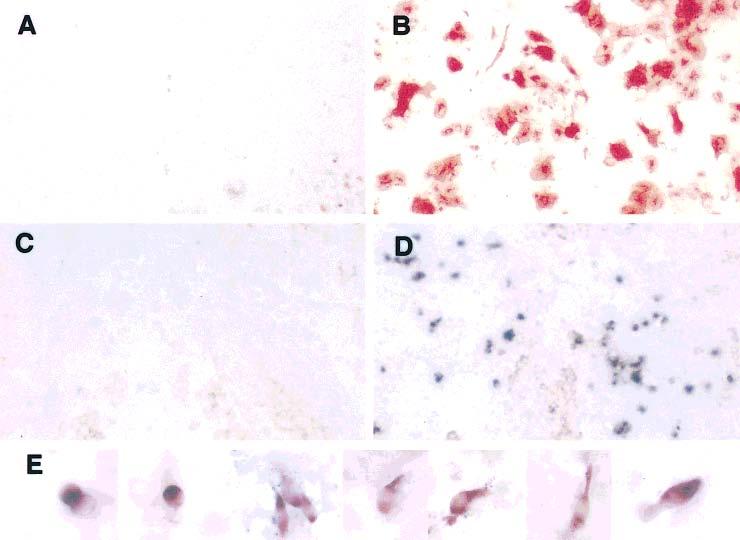

Figure 5.

Changes in gene expression and cell morphology in RPE cell cultures infected with retroviruses expressing neuroD. Forced expression of neuroD in RPE cell cultures yielded HNK-1/N-CAM–positive cells (B) and visinin mRNA-positive cells (D), both of which were absent from the corresponding controls [(A) and (C), respectively]. While cells positive for HNK-1/N-CAM appeared to be nonneural, with flat cell bodies in young cultures, cells expressing visinin clearly took up various morphologies of immature photoreceptor cells (E), from immediately after terminal mitosis (far left) progressing toward developing of an inner segment (middle and right), which are highlighted by in situ hybridization signals. Some even have an outer segment-like process apical to the inner segment. Magnifications: (A–D) ×25; (E) ×100.

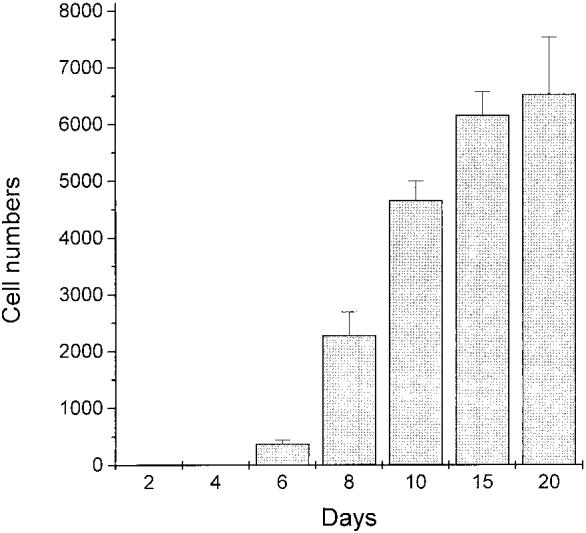

Retinal pigment epithelium cell cultures were directly examined for the presence of photoreceptor cells through in situ hybridization with an antisense RNA probe against visinin. Starting from day 6 after infection, cells expressing visinin became detectable [Figs. 5(D) and 6]. No such positive cells were detected at day 2 or 4 after infection (Fig. 6). This indicates that the visinin mRNA-positive cells did not result from retinal contamination, but were produced de novo. The number of cells expressing visinin increased from day 6 to day 20 after infection (Fig. 6). No visinin mRNA-positive cells were detected in control cultures infected with viruses expressing GFP [Fig. 5(C) and Table 1]. Cells expressing visinin exhibited morphologies typical of photoreceptor cells at different developmental stages under culture conditions (Madreperla et al., 1989), from an oval shape [Fig. 5(E), far left] to an elongated cell body with an inner segment compartment highlighted by visinin in situ hybridization signals [Fig. 5(E), middle and right]. Apical to the inner segment, an outer segment-like process which did not contain much of the hybridization signal was present in some cells [Fig. 5(E)].

Figure 6.

The number of cells expressing visinin detected at various time points after the administration of viruses expressing neuroD to E6 RPE cultures. Expression of neuroD produced visinin-expressing cells, which were first detected at day 6, but were absent at days 2 and 4. More visinin-expressing cells were detected in older cultures up to day 20, the last time point in this study. The number of cells expressing visinin per 22 mm2 is given as mean (±S.E.M.) derived from at least three independent experiments, each with three dishes counted at each time point.

Table 1.

Markers, Their Specificity in the Retina, and the Numbers of Cells (per 22 mm2) They Labeled in E6 RPE Cultures Infected with Viruses Expressing GFP or neuroD

| Visinin* | MAP2† | RA4‡ | chx10§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photoreceptor | + | + | – | – |

| Horizontal | – | + | – | – |

| Bipolar | – | – | – | + |

| Amacrine | – | + | – | – |

| Ganglion | – | + | + | – |

| GFP | ||||

| Day 8 | 0 | 36 ± 6 | 52 ± 27 | 0 |

| Day 20 | 0 | 46 ± 5 | 70 ± 14 | ND |

| neuroD | ||||

| Day 8 | 2285 ± 413 | 2234 ± 338 | 100 ± 23 | 0 |

| Day 15 | 6164 ± 408 | 5706 ± 540 | 94 ± 15 | 0 |

| Day 20 | 6532 ± 1006 | 5109 ± 192 | 74 ± 19 | ND |

Mean (±S.E.M.) were calculated from data obtained from at least three independent experiments, each with three dishes used for a single marker. ND = not determined.

Tucker and Matus (1987); our unpublished observations.

To address whether photoreceptor cells were the primary products of neuroD-induced transdifferentiation, different markers (Table 1) were used to examine the presence of other neural cells. They included (a) RA4; (b) monoclonal antibody against MAP2, which labels all major types of retinal cells except bipolar cells (Tucker and Matus, 1987; Tucker et al., 1988; our unpublished data); and (c) chx10, which is expressed in young bipolar cells (Belecky-Adams et al., 1997). No chx10 mRNA-positive cells were detected in any of the cultures expressing either neuroD or GFP (Table 1). A small number of cells (≤100 ± 23 cells/22-mm2 area) were positive for RA4 in cultures infected with viruses expressing either neuroD or GFP (Table 1). While < 100 cells were stained with anti-MAP2 antibody in the control, the number jumped to thousands in cultures infected with viruses expressing neuroD (Table 1). Notably, the number of cells labeled with anti-MAP2 was very close to, but never exceeded that expressing visinin (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Expression of neuroD and the Genesis of Photoreceptor Cells

The retinal neuroepithelium is a pseudo-stratified structure containing proliferating neuroblasts and differentiating neurons. During retinal neurogenesis, accumulation of postmitotic, differentiating retinal cells takes place at different anatomical locations for different cell types. For example, the first group of cells born, the ganglion cells, accumulates along the vitreal surface, whereas the photoreceptor cells, which are born later, accumulate on the opposite side of the retinal neuroepithelium adjacent to the RPE. The last group of dividing progenitor cells may be found inside the INL (Sharma and Ehinger, 1997). In light of this, the restricted expression of neuroD detected at the outer portion of the retinal neuroepithelium, an anatomical location where young, visinin-expressing photoreceptor cells are found, suggests that cells expressing neuroD may be young photoreceptor cells or their precursors. This speculation is supported by the evidence that cells expressing neuroD were primarily located at the center of rosettes in a retinal cell culture or were confined to the ONL in a retina with stratified structure.

A high level of neuroD expression was detected in the retina at E5, when the expression of visinin was minimal. This suggests that the expression of neuroD precedes that of visinin and is consistent with the notion that cell fate determination precedes cell differentiation. A decrease in neuroD expression was first noticed in the central region of E7 retina. This temporal pattern of expression suggests a concurrence of neuroD expression and the genesis of photoreceptor cells, reported to be born on E6 (Belecky-Adams et al., 1996), and implies that the gene may be involved in photoreceptor genesis.

Previous reports by different groups described various patterns of neuroD expression in the retina of different species (Acharya et al., 1997; Roztocil et al., 1997; Kanekar et al., 1997). While many factors (such as differences between species) may be responsible for the discrepancy, the specificity of in situ hybridization may play a role. We have found that a high-stringency final wash (0.1 × SSC for 1 h at 70°C) after RNase A treatment is necessary to obtain specific in situ hybridization signals. Otherwise, false-positive signals prevail, particularly if the probes include the entire bHLH region [as was the case in Roztocil et al., 1997]. This region is highly conserved among members of the neuroD subfamily, and homology in this region extends to other bHLH proteins. The specificity of the in situ hybridization may also contribute to the difference in the distribution of neuroD mRNA described in this report from that of Acharya et al. (1997); their signals highlighted the nucleus, not the cytoplasm.

Role of neuroD in Photoreceptor Cell Production

Indiscriminate expression of neuroD through replication-competent, transformation-deficient retroviruses in retinal neuroblasts produced a retina with an extra layer of cells in the ONL. Quantitative analyses of disassociated retina cells revealed that the number of cell expressing visinin increased by 57.7%. Both histological analysis and quantitative analysis revealed no significant changes in the number of ganglion cells, even though misexpression of neuroD in ganglion precursors was evident, as revealed by double-labeling with anti-P27 antibody and RA4 (data not shown). In addition, the number of INL neurons that express either pax6 or chx10 was not changed. This suggests that neuroD either (a) transdifferentiated some RPE cells into photoreceptor cells; (b) increased the proliferation of progenitors belonging to the photoreceptor lineage; (c) increased the survival of young photoreceptor cells; (d) recruited some multipotent progenitors into a photoreceptor cell fate; or (e) switched the fate of some precursors, which otherwise would differentiated into retinal cells other than photoreceptors. Further studies will be required to distinguish among these possibilities. Nevertheless, our observation that expression of neuroD in RPE cells led to the production of cone photoreceptors but not other cell types argues for a dramatic role of neuroD in establishing cell identity. This model of neuroD function as a determination factor for a certain cell type is consistent with what has been proposed by Lee et al. (1995). Unlike the dramatic effect on photoreceptor cell production observed with neuroD overexpression, studies with retrovirus-driven misexpression of crx in mouse suggested that crx is not sufficient to instruct the rod photoreceptor cell fate (Furukawa et al., 1997). This and the expression pattern argue that neuroD may act upstream of crx and other genes involved in the unfolding of photoreceptor cell differentiation programs. It should be pointed out that because of heterodimerization among bHLH proteins, it is possible that additional bHLH proteins may be relevant to photoreceptor fate selection process, and the effect of neuroD overexpression we have observed might be a result of perturbing a complex equilibrium of hetero- and homodimeric species.

RPE Transdifferentiation Triggered by neuroD

The vertebrate retina and RPE originate from the same neuroepithelial tissue—the optic vesicle. Un like retinal neurons, RPE cells can reenter the cell cycle if stimulated, and their progeny can adopt a fate other than presumptive retinal pigment cells (Coulombre and Coulombre, 1965; Park and Hollenberg, 1989; Pittack et al., 1991; Opas and Dziak, 1994). We explored the possibility of using RPE cell cultures to test the hypothesis that neuroD expression increases the probability that a cell will ensure a photoreceptor fate. In E6 RPE cells in fected with the neuroD retrovirus, anti-HNK-1/N-CAM immunoreactivity was detected at day 4 after addition of virus. Subsequently, cells expressing visinin emerged at day 6, but not before, and their numbers increased from day 6 to day 20, suggesting a continuous generation of photoreceptor cells in the culture. In addition to expressing visinin, the transdifferentiated cells also underwent morphological changes such that they resembled young photo-receptor cells with elongated cell bodies and inner segment compartments. Some showed outer segment–like processes.

Analysis of neuronal populations in transdiffer entiated RPE cultures revealed no cells positive for chx10 mRNA, suggesting that bipolar cells are un likely to be present in the transdifferentiated culture.All cultures, including controls, contained a small number of RA4-positive cells, which might be generated as a result of growth factors, such as basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), in the fetal calfserum. bFGF promotes transdifferentiation into RA4-positive cells (our unpublished data). Anti-MAP2 antibody, which labels amacrine cells, horizontal cells, ganglion cells, and photoreceptor cells, labeled a significant number of cells in the transdifferentiated RPE cell cultures. However, nonphotoreceptor cells are unlikely to be present in significant numbers, because the number of MAP2 positive cells approached, but never exceeded, that of visinin-positive cells at three time points (days 8, 15, and 20) (Table 1). The absence of other retinal cell types is unlikely to be due to a nonpermissive culturing condition, since they were detected in RPE cultures transduced with retroviruses expressing a bHLH gene belonging to the neurogenin subfamily (our unpublished observations). Together, these observations imply that photoreceptor cells may be the major, if not the only, type of retinal neurons generated from RPE cell transdifferentiation induced by neuroD. Unlike bFGF, which induces RPE transdifferentiation through dedifferentiation into proliferative blast cells from which different types of retinal cells are then derived, neuroD alone can change a cell from an RPE phenotype to a cone phenotype. This raises the possibility of employing neuroD as a molecular trigger to regenerate photoreceptor cells in vivo or in vitro aiming at visual rescue in various animal models for human retinal degenerations (Bennett et al., 1996).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Stephen Hughes for retroviral vector, RCAS (B/P), and shuttle vector Cla12Nco; Dr.Steven McLoon for RA4 antibody; Dr. Ray Dacheux for instructions on microinjection; and Dr. Christine Curcio and Dr. Kent Keyser for comments and suggestions on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH Grant EY11640 and by a pilot project grant from the Vision Science Research Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Footnotes

Contract grant sponsor: NIH; contract grant number: EY11640

Contract grant sponsor: Vision Science Research Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham

REFERENCES

- Acharya HR, Dooley CM, Thoreson WB, Ahmad I. cDNA cloning and expression analysis of NeuroD mRNA in human retina. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;233:459–463. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexiades M, Cepko CL. Subsets of retinal progenitors display temporally regulated and distinct biases in the fates of their progeny. Development. 1997;124:1119–1131. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.6.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allikmets R, Shroyer NF, Singh N, Seddon JM, Lewis RA, Bernstein PS, Peiffer A, Zabriskie NA, Li Y, Hutchinson A, Dean M, Lupski JR, Leppert M. Mutation of the Stargardt disease gene (ABCR) in age-related macular degeneration. Science. 1997a;277:1805–1807. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5333.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allikmets R, Singh N, Sun H, Shroyer NF, Hutchinson A, Chidambaram A, Gerrard B, Baird L, Stauffer D, Peiffer A, Rattner A, Smallwood P, Li Y, Anderson KL, Lewis RA, Nathans J, Leppert M, Dean M, Lupski JR. A photoreceptor cell-specific ATP-binding transporter gene (ABCR) is mutated in recessive Stargardt macular dystrophy. Nat. Genet. 1997b;15:236–246. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belecky-Adams T, Cook B, Adler R. Correlations between terminal mitosis and differentiated fate of retinal precursor cells in vivo and in vitro: analysis with the “window-labeling” technique. Dev. Biol. 1996;178:304–315. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belecky-Adams T, Tomarev S, Li HS, Ploder L, McInnes RR, Sundin O, Adler R. Pax-6, Prox 1, and Chx10 homeobox gene expression correlates with phenotypic fate of retinal precursor cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1997;38:1293–1303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J, Tanabe T, Sun D, Zeng Y, Kjeldbye H, Gouras P, Maguire A. Photoreceptor cell rescue in retinal degeneration (rd) mice by in vivo gene therapy. Nat. Med. 1996;2:649–654. doi: 10.1038/nm0696-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Wang Q-L, Nie Z, Sun H, Lennon G, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Kenkins NA, Zack D. Crx, a novel otx-like paired-homeodomain protein, binds to and transactivates photoreceptor cell-specific genes. Neuron. 1997;19:1017–1030. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80394-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulombre JL, Coulombre AJ. Regeneration of neural retina from the pigmented epithelium in the chick embryo. Dev. Biol. 1965;12:79–92. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(65)90022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete, Cepko CL. Replication-competent retroviral vectors encoding alkaline phosphatase reveal spatial restriction of viral gene expression/transduction in the chick embryo. Mol. Cell Biol. 1993;13:2604–2613. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa Y, Morrow EM, Cepko CL. Crx, a novel otx-like homeobox gene, shows photoreceptor-specific expression and regulates photo-receptor differentiation. Cell. 1997;91:531–541. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger V, Hamilton HL. A series of normal stages in the development of the chick embryo. J. Morphol. 1951;88:49–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Moody SA. Three types of serotonin-containing amacrine cells in tadpole retina have distinct clonal origins. J. Comp. Neurol. 1997;387:42–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes SH, Greenhouse JJ, Petropoulos CJ, Sutrave P. Adaptor plasmids simplify the insertion of foreign DNA into helper-independent retroviral vectors. J. Virol. 1987;61:3004–3012. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.10.3004-3012.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanekar S, Perron M, Dorsky R, Harris WA, Jan LY, Jan YN, Vetter ML. Xath5 participates in a network of bHLH genes in the developing Xenopus retina. Neuron. 1997;19:981–994. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80391-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley MW, Turner JK, Reh TA. Retinoic acid promotes differentiation of photoreceptors in vitro. Development. 1994;120:2091–2102. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.8.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JE, Hollenberg SM, Snider L, Turner DL, Lipnick N, Weintraub H. Conversion of Xenopus ectoderm into neurons by NeuroD, a basic helix–loop–helix protein. Science. 1995;268:836–844. doi: 10.1126/science.7754368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H-S, Yang J-M, Jacobson RD, Pasko D, Sundin O. pax6 is first expressed in a region of ectoderm anterior to the early neural plate: implications for stepwise determination of the lens. Dev. Biol. 1994;162:181–194. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madreperla SA, Edidin M, Adler R. Na+, K+-adenosine triphosphatase polarity in retinal photoreceptors: a role for cytoskeletal attachments. J. Cell Biol. 1989;109:1483–1493. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.4.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris VB, Shorey CD. An electron microscope study of types of receptor in the chick retina. J. Comp. Neurobiol. 1967;129:313–340. doi: 10.1002/cne.901290404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naya FJ, Huang HP, Qiu Y, Mutoh H, DeMayo FJ, Leiter AB, Tsai MJ. Diabetes, defective pancreatic morphogenesis, and abnormal enteroendocrine differentiation in BETA2/neuroD-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2323–2334. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordlander RH. HNK-1 marks earliest axonal outgrowth in Xenopus. Dev. Brain Res. 1989;50:147–153. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(89)90135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opas M, Dziak E. bFGF-induced transdifferentiation of RPE to neuronal progenitors is regulated by the mechanical properties of the substratum. Dev. Biol. 1994;161:440–454. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CM, Hollenber MJ. Basic fibro-blast growth factor induces retinal regeneration in vivo. Dev. Biol. 1989;134:201–205. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittack C, Jones M, Reh TA. Basic fibroblast growth factor induces retinal pigment epithe lium to generate neural retina in vitro. Development. 1991;113:577–588. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.2.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin G, Turgeon B, Drouin J. NeuroD1/beta2 contributes to cell-specific transcription of the proopiomelanocortin gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;117:6673–6682. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond PA. Cell determination and positional cues in the teleost retina: development of photo-receptors and horizontal cells. In: Lam D-K, Shatz CJ, editors. Development of the Visual System. MIT Press; Cambridge: 1991. pp. 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Reh TA. Determination of cell fate during retinal histogenesis: Intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms. In: Lam D-K, Shatz CJ, editors. Development of the Visual System. MIT Press; Cambridge: 1991. pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Roztocil T, Matter-Sadzinski L, Alliod C, Ballivet M, Matter JM. NeuroM, a neural helix–loop–helix transcription factor, defines a new transition stage in neurogenesis. Development. 1997;124:3263–3272. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.17.3263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab MH, Druffel-Augustin S, Gass P, Jung M, Klugmann M, Bartholomae A, Rossner MJ, Nave KA. Neuronal basic helix–loop–helix proteins (NEX, neuroD, NDRF): spatio-temporal expression and targeted disruption of the NEX gene in transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:1408–1418. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-04-01408.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma RK, Ehinger B. Mitosis in developing rabbit retina: an immunohistochemical study. Exp. Eye Res. 1997;64:97–106. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Nathans J. Stargardt's ABCR is localized to the disc membrane of retinal rod outer segments. Nat. Genet. 1997;17:15–16. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker RP, Binder LI, Matus AI. Differential location of the high- and low-molecular weight variants of MAP2 in the developing retina. Dev. Brain Res. 1988;38:313–318. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(88)90059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker RP, Matus AI. Developmental regulation of two microtubule-associated proteins (MAP2 and MAP5) in the embryonic avian retina. Development. 1987;101:535–546. doi: 10.1242/dev.101.3.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner DL, Cepko CL. A common progenitor for neurons and glial persists in rat retina late in development. Nature. 1987;328:131–136. doi: 10.1038/328131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waid DK, McLoon SC. Immediate differentiation of ganglion cells following mitosis in the developing retina. Neuron. 1995;14:117–124. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90245-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S-Z, Adler R. A developmentally regulated basic-leucine zipper-like gene and its expression in embryonic retina and lens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:1351–1355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T, Pfaff SL, Edlund T, Jessell TM. Control of cell pattern in the neural tube: motor neuron induction by diffusible factors from notochord and floor plate. Cell. 1993;73:673–686. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90248-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata K, Goto K, Kuo CH, Kondo H, Miki N. Visinin: a novel calcium binding protein expressed in retinal cone cells. Neuron. 1990;4:469–476. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90059-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan R-T, Wang S-Z. Identification and characterization of tenp, a gene transiently expressed before overt cell differentiation during neurogenesis. J. Neurobiol. 1998;34:319–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, Rizzolo LJ, Barnstable CJ. Differentiation and transdifferentiation of the retinal pigment epithelium. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1997;171:225–265. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62589-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]