Summary

Calorie restriction (CR) and late-onset CR enhance longevity in many organisms. Resource allocation theory suggests that longevity is enhanced by increasing somatic storage, at the expense of current reproduction. Phytophagous insects accumulate amino acids as hemolymph storage proteins for major developmental events. We hypothesized that protein storage is involved in life extension from CR. In a longitudinal experiment, we tested whether CR altered protein storage in female grasshoppers. Individuals on CR (60% or 70%) or late-onset CR had at least 60% greater longevity than ad libitum individuals. Age at first oviposition, dry mass of the first clutch, or lifetime fecundity were not affected by CR, but CR did increase the number of clutches produced. Most important, females on life-extending CR and late-onset CR did not differ in the concentration of hemolymph storage of proteins in comparison to ad libitum females. Protein storage changed with time in all groups, demonstrating sufficient sensitivity in our methods. Previous experiments have shown that severe CR (~30% of ad libitum) can reduce hemolymph storage. Therefore, the reduction in intake needed to extend lifespan is not sufficient to reduce protein storage in the hemolymph. These results do not support the hypothesis that protein storage is involved in life extension from CR.

Keywords: Nutrient storage, storage proteins, hexamerins, phenotypic plasticity, life history

Introduction

Resource allocation theory suggests that longevity can be enhanced by increasing somatic storage at the expense of development or current reproduction (e.g., Kirkwood 1987; 2002). Longevity can be extended by artificial selection, genetic engineering, or calorie restriction, and evidence from all three of these treatments generally has supported resource allocation theory. The increased storage due to genetic differences has been quantified in lines of fruit flies artificially selected for delayed fecundity and increased lifespan (Rose 1991). Lines of flies selected for greater lifespan had lower fecundity (as number of eggs) but greater whole body carbohydrate and lipid storage than did control lines (Djawdan et al. 1996). Similarly, long-lived mutants can show enhanced longevity and storage. For example, an insulin-like receptor mutation results in female flies with an 85% increase in lifespan and 4-fold higher fat storage (Tatar et al. 2001).

The effects of calorie restriction (CR) on nutrient storage are not completely understood. Calorie restriction enhances longevity in yeast, worms, fruit flies, mice, and other organisms (Longo and Finch 2003; Tatar et al. 2003). Late-onset CR can also enhance longevity (e.g., Weindruch and Walford 1988; Pugh et al. 1999) and has been shown to reduce mortality rate within 48 h in flies (Mair et al. 2003) and to rapidly alter gene expression in mice (Cao et al. 2001; Dhahbi et al. 2004). Late-onset CR provides an additional means for testing the role of nutrient storage on longevity.

Calorie restriction in insects is generally thought to enhance nutrient storage. Simmons and Bradley (1997) studied the effects of dietary protein on storage in Drosophila by feeding female flies different levels of live yeast. Availability of yeast was positively associated with fecundity, body weight and metabolic rate, but negatively associated with whole body carbohydrates and lipids (Simmons and Bradley 1997). Together, the studies by Djawdan et al. (1996) and Simmons and Bradley (1997) suggest that long-lived insects increase storage of carbohydrates and lipids. However, insects are well known to store proteins as well as carbohydrates and lipids (e.g., Haunerland 1996). Further, proteins are the limiting nutrient for development in many insects. Despite this, we know of no tests on the potential role of stored protein in longevity. To address this gap in our knowledge, in this paper we test the role of protein storage in long-lived insects. We test the hypothesis that protein storage is altered when food availability is reduced sufficiently to extend lifespan.

Protein is the limiting nutrient for both development to the next molt and egg production in phytophagous insects (Chapman 1998). In contrast to most vertebrates, insects can store high numbers of amino acids. This ability to store amino acids is particularly critical for phytophagous insects on limiting diets such as CR. Insects store amino acids as hexamerins, a conserved superfamily of storage proteins, usually made of six ~75kDa subunits (Haunerland 1996). The main depot for proteins in insects is the hemolymph (Chapman 1998). The hemolymph is an important storage organ in arthropods; hemolymph is ~30% of the body mass of insects, while blood is ~10% of the body mass in mammals (Marieb 2005). Hexamerins are produced in the fat body and then secreted in the hemolymph for storage. The role of hemolymph protein stores in long-lived insects is unknown.

Many insects have the ability to resorb developing oocytes when the diet is limited (Stauffer and Whitman 1997; Chapman 1998). Because oocytes are nearly half vitellin, this redistribution of protein could result in an increase in protein storage in the hemolymph, which could potentially be used for longevity. This serves as a conceivable mechanism by which somatic protein storage could be increased upon CR, at the cost of reproduction. Grasshoppers are model organisms that are large enough (up to 15 g) to be individually tracked and sampled throughout adulthood, yet short-lived enough (~80 d) for practical experiments. In addition, because grasshoppers in experiments are reared singly, the exact amount of food consumption can be quantified. Neither tracking the hemolymph of individuals nor measuring consumption is easily possible in the common invertebrate models of aging, namely Drosophila and C. elegans. Hence, we have begun examining effects of CR on longevity and protein storage in the Eastern lubber grasshopper, Romalea microptera.

The effects of diet quantity on egg production in the lubber grasshoppers, and in particular the physiology underlying the first clutch, have been well studied. A severe adult CR (post-hoc estimated to be ~30% of ad libitum feeding) approximately doubles the time until first oviposition (Hatle et al. 2000). Through the early fecundity vs. longevity trade-off, this delayed reproduction could be predicted to be associated with greater longevity.

Hemolymph protein level is a strong predictor of the number of eggs produced. About 80% of total hemolymph protein is held in three hexameric storage proteins (Hatle et al. 2001). In previous experiments we analyzed single hemolymph protein samples by two methods: native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with subsequent densitometry of each storage protein, and simple total hemolymph protein determination by the Bradford dye assay (1976). These two types of analysis always produced the same qualitative conclusions (MJ Hathaway, JD Hatle, and DW Borst, in preparation). During production of the first clutch, storage protein levels rise monotonically to a peak ~12 days before oviposition, then levels fall steadily until laying. In concert with the pattern of oocyte growth, this protein profile suggests amino acids are stored in the hemolymph proteins and later invested in egg production. On severe CR (~30%), the peak level of hemolymph protein is reduced by ~40%, and the peak is greatly delayed (Hatle et al. 2001; 2004). Peak titers of the major gonadotropins, juvenile hormone and ecdysteroids (Hatle et al. 2000; 2003b), and the egg-yolk precursor protein vitellogenin (Hatle et al. 2001), are similarly delayed.

In the present longitudinal experiment, we address the hypothesis that protein storage is involved in the extension of lifespan by CR or late-onset CR. We test whether CR and late-onset CR in adult females enhances longevity or increases hemolymph protein storage in the hemolymph of lubber grasshoppers.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animals and rearing

We collected juvenile Romalea microptera in Jacksonville, FL, USA, and reared them in the lab to adulthood en masse at room temperature. These wild caught grasshoppers were used in the main experiment reported here. They were fed Romaine lettuce ad libitum, and green beans and green onions occasionally. On the day an individual molted to adult it was transferred to a 500 cc ventilated plastic container at a 14L:10D photoperiod with a corresponding 32ºC:24ºC thermocycle. R. microptera are univoltine, so all animals in this experiment were in approximate developmental synchrony, with all adults appearing within a 2 week timeframe. We ran parallel experiments with both males and females, but because only 8 males had died when the experiment was terminated, we report data only for females.

Diet regimens

We tested four diet regimens on longevity and protein storage: ad libitum, 60% diet, 70% diet, and late-onset CR (Table 1). The diet reduction in the late-onset CR group was chosen to occur after laying the first clutch and during the yolking of the second clutch. The amount of food consumed by female grasshoppers fed ad libitum, and therefore the amount to offer for 60% and 70% diets, was not known prior to this study. Hence, as the experiment progressed, we measured the amount consumed by the ad libitum group and used these data to calculate the amount to offer the CR groups. Because the amount of food consumed by female lubber grasshoppers during adulthood is variable (see Fig. 1), this required constant adjustment of the amount offered to the CR groups. We had four, planned pairwise comparisons within the four diets: ad libitium vs. each of the other three diets, and 60% diet vs. late-onset CR.

Table 1.

Romaine lettuce diet treatments offered to adult female lubber grasshoppers. Females were also offered ~5 oatmeal flakes daily. Day 50 was chosen as the start date for late-onset CR because it is after the production of the first clutch but well before the age of median death in ad libitum fed females.

| Diet treatment | Romaine lettuce offered |

|---|---|

| Ad libitum | Constant, free access to lettuce |

| 60% diet | Calorie restriction at 60% of that consumed by the ad libitum group |

| 70% diet | Calorie restriction at 70% of that consumed by the ad libitum group |

| Late-onset CR | Constant, free access to lettuce for the first 49 days of adulthood, then the 60% diet from day 50 until death |

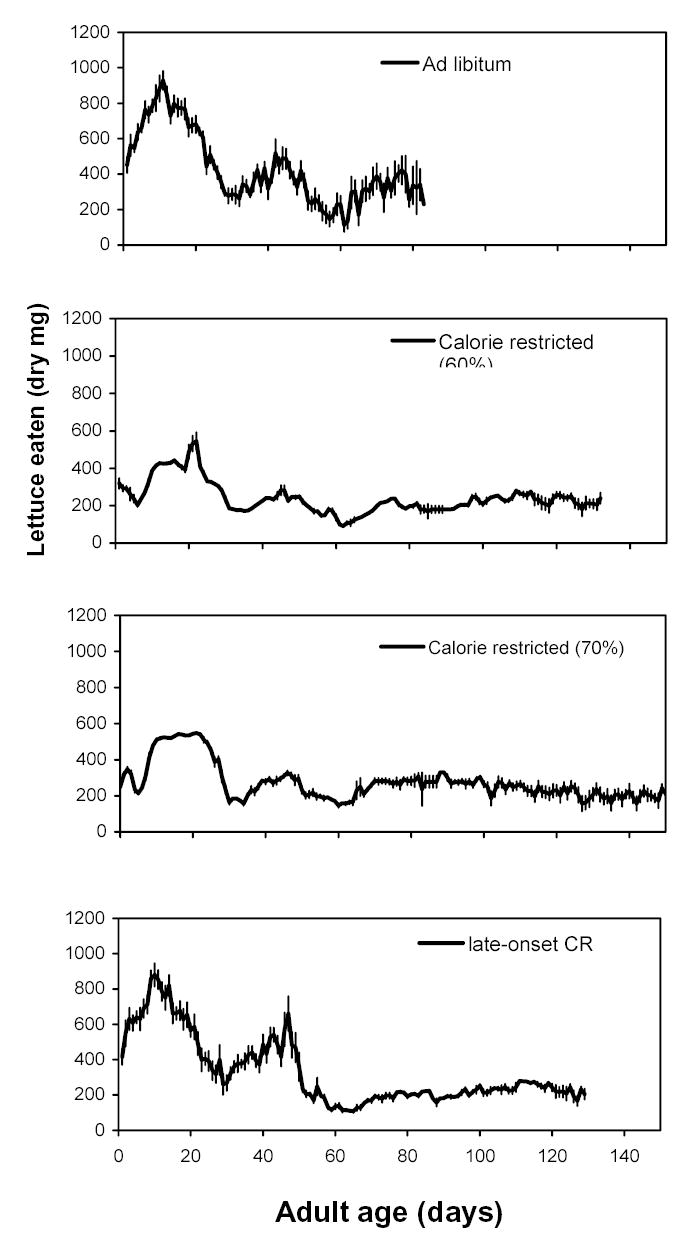

Figure 1.

Romaine lettuce consumed by female lubber grasshoppers on four diet treatments. Lettuce weights are presented as dry mass consumed per day. Diet treatments were effective in manipulating the amount of lettuce consumed. The late-onset CR group was offered free access to lettuce the first 49 days, then fed identically to the calorie restricted (60%) group from day 50 until death. The plot line for each group ends at the median age at death for that group.

Assignment to treatment groups

Individuals were assigned to the 4 feeding treatments by a counterbalanced method. That is, half of the ad libitum group were placed, then all individuals in the other groups were placed, then the remaining half the ad libitum group was placed. This method of assignment was necessary because the amount consumed by the ad libitum group determined the amount of food to offer other groups, so at least part of this group had to be in place first. Our sample sizes were 10–12 grasshoppers in each feeding treatment.

Body masses

We measured wet masses of the live grasshoppers immediately before feeding each day. Because we have observed lubber grasshoppers consume 1.5 g lettuce meals in 20 min without defecating, we know that they can hold up to 1.5 g of wet lettuce in their gut. Our anecdotal observations suggest this is near the maximum meal size. Much of this 1.5 g of freshly consumed lettuce is ultimately defecated, and not absorbed. Because individuals from the ad libitum group might have eaten immediately before weighing, but the calorie restricted groups were without food immediately before weighing, the comparison of body masses across treatment groups is potentially biased. Nonetheless, these measures of body masses are estimates of the growth trajectories of the feeding groups, and differences greater than 2 g could be important.

Reproductive tactics

Typically, CR acts in part by delaying or reducing investment in reproduction, through a trade-off between early fecundity and longevity (Rose 1991). Hence, we quantified reproductive output. All females were unmated, which does not delay oocyte development or oviposition in this species (Walker et al. 1999). We did not place females on oviposition substrate; Mefferd et al. (2005) showed that this delays laying ~6 days, but does not appear to delay the yolking of the subsequent clutch. When a female laid, the age of oviposition was recorded, the egg pod was collected and dried overnight at 55°C, and the dry weight of the egg pod was measured. Lifetime fecundity was estimated as the cumulative mass of egg pods laid by an individual female. Samples sizes for reproductive tactics were 8 – 11 per group.

Hemolymph samples

From half of the individuals, we collected serial hemolymph samples (see Hatle et al. 2000 for methods) for determination of total proteins and lipids. Samples were collected every 7 days, beginning at median day 15 (range 14 – 18). They were stored in hemolymph buffer (see Hatle et al. 2001) at −20ºC until analysis. Total hemolymph protein levels were determined using the Bradford (1976) assay with bovine serum albumin standards.

After proteins had been determined, we extracted the samples for lipid quantification. Lipids are an important store in female phytophagous insects, because their diet is high in carbohydrates and low in lipid and protein (Behmer and Nes 2003), and nearly half of an insect egg is lipids (Chapman 1998). Lipids are stored as triglycerides in the fat body and transported as diglycerides through the hemolymph. Only hemolymph lipids can be tested serially in the same individual, so we measured total hemolymph lipids as a snapshot of the amount of lipid being transported by an individual. To measure lipids from the hemolymph samples in buffer, we added acetone, vigorously mixed to extract the lipids from the sample, and removed an aliquot containing 1 μl hemolymph equivalents. The aliquot was tested for total lipids by the phosphovanillin assay, using vegetable oil standards (e.g., Hatle and Spring 1999).

Storage of protein in hemolymph and fat body

Mair et al. (2003) found that mortality rates of fruit flies were reduced after only 48 h on late-onset CR. Hence, we further tested the dynamics of protein storage in response to late-onset CR in two separate experiments. First, we raised grasshoppers on ad libitum (n=15), CR (n=8) and late-onset CR started at day 50 (n=13) diets as before. We collected hemolymph samples from all grasshoppers at days 45, 48, 52 and 55 (± 1 day for each sample) and measured total hemolymph protein. In this experiment, the CR diet was 2.1 g lettuce / day, which was ~60% of that consumed by the ad libitum group.

Second, we tested the effects of short-term diet restriction on total protein in the fat body. Fat body protein is best seen as an index of total protein production. Previous experiments incubating fat body with radiolabeled amino acids have shown that most of the protein produced by the fat body is hexameric storage protein (Hathaway, Hatle, and Borst, in preparation). Hence, total fat body protein can be seen as an estimate of future storage. Grasshoppers were reared on ad libitum diets until day 50, then kept on ad libitum, starvation (water only) or severe CR (1.5 g lettuce / day) diets for the next 48 h. An additional group was kept on the ad libitum diet throughout, and then heat shocked at 48°C for 60 min immediately before dissection; this heat shock group served as a positive control for the experiment, because heat shock is well known to rapidly decrease fat body total protein. Grasshoppers were then dissected, all the abdominal fat body was removed and homogenized in buffer with protease inhibitor, and total protein content of the fat body was measured. A parallel experiment was run in which treatments were begun at day 20, when these grasshoppers are in mid-vitellogenesis for the first clutch. The median number of grasshoppers in each diet group was 7 or 8, while the number of grasshoppers in each heat shock group was 4.

Experimental Results

Amounts eaten

Female lubber grasshoppers given free access to lettuce increased consumption from adult molt until day 11, decreased consumption until day 31, and then increased consumption again to day 41 (Fig. 1). This fluctuation seems to vary with the preparation for production of clutches. Feeding rates are highest during the first half of clutch production and lowest about a week before the oocytes are chorionated and ready to lay.

Our methods were successful in manipulating the amounts consumed by each treatment group. Through the median age at death for the ad libitum group (day 83), the 60% diet group ate 58.8% of the lettuce eaten by the ad libitum group and the 70% diet group ate 71.2% of that eaten by the ad libitum group. The late-onset CR group ate 99.8% of that eaten by the ad libitum group before the diet switch (days 0 – 50), but only 61.7% of that eaten by the ad libitum group after the diet switch (days 51 – 81).

Body masses

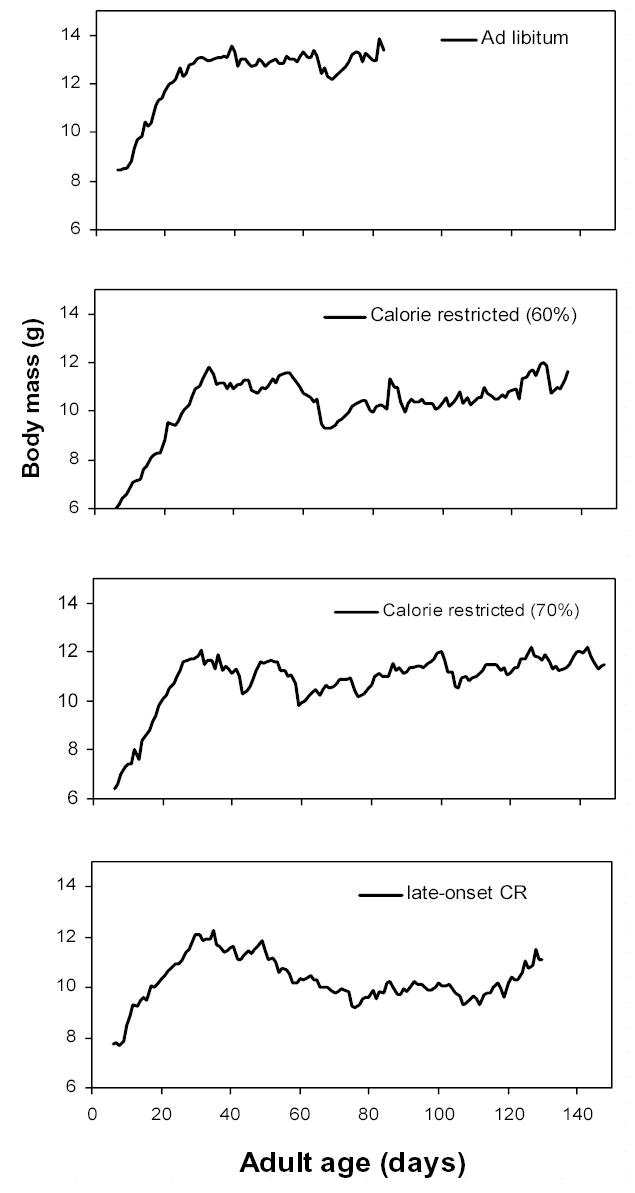

The ad libitum group appears to have grown more rapidly than the 60% diet group (Fig. 2). Body masses may be biased by unabsorbed food held in the gut, so only differences of at least 2 g were considered. From days 6 – 10, a major somatic growth phase for these grasshoppers (Sundberg et al. 2001), body masses of the ad libitum group average > 2 g more than the 60% diet group. Similarly, mean body masses of the ad libitum group were > 2 g more than the 60% diet during production of the second clutch (~days 45 – 65). These data weakly suggest that calorie restriction reduces growth and body size in lubber grasshoppers.

Figure 2.

Wet body mass immediately before feeding female lubber grasshoppers on four diet treatments. The late-onset CR group began on a reduced diet at day 50. See Table 1 for further descriptions of diets. Calorie restriction may have slightly reduced body mass.

Survivorship

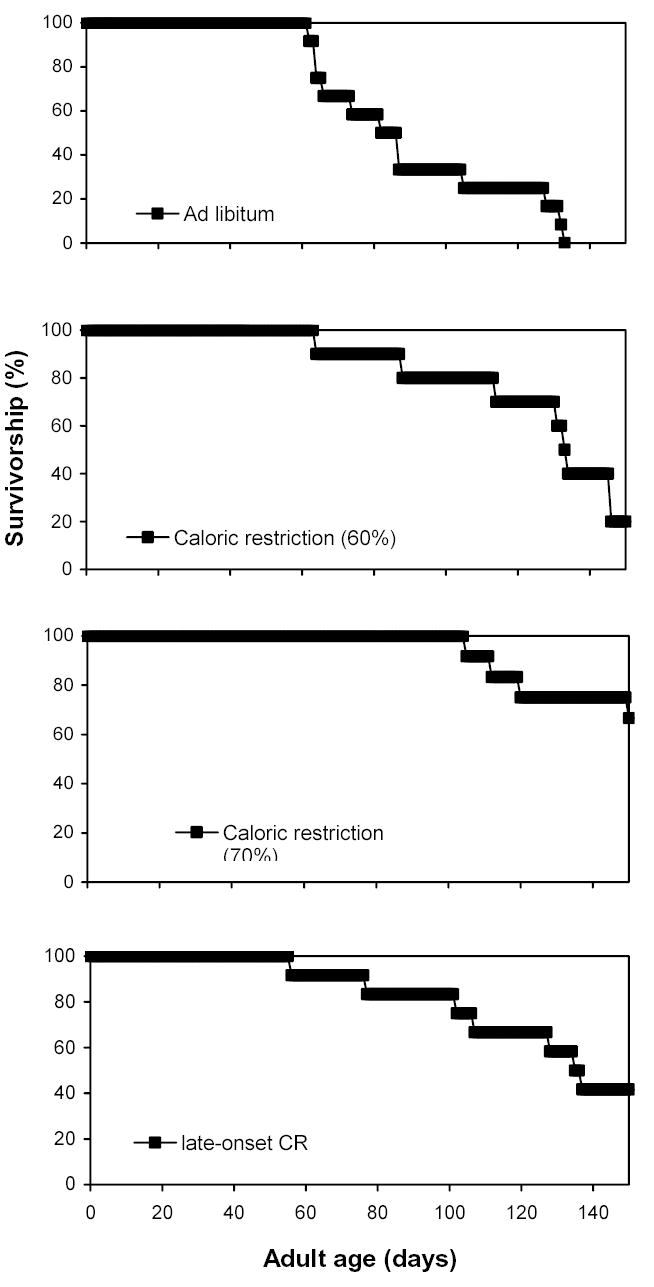

Median ages at death were compared using the Kaplan-Meier time-failure analysis (SAS Proc LifeTest; SAS Institute Inc., 1999). The median ages at death, in days, were: ad libitum – 83; 60% diet – 135; 70% diet – greater than 165; late-onset CR – 136 (Fig. 3). The medians were significantly different (Wilcoxon χ2 = 22.5; df = 4; P = 0.0002). We conducted the four planned, pairwise post-tests (Bonferroni-corrected α = 0.01): ad libitum vs. each of the other three diets, and 60% diet vs. late-onset CR. The 60% diet (χ2 = 1863; P << 0.001), the 70% diet (71%; χ2 = 3096; P << 0.001), and late-onset CR diet (χ2 = 1739; P << 0.001) all had much greater longevity than the ad libitum group (pairwise Kaplan-Meier time-failure analyses; all df = 1). The late-onset CR group had greater longevity than the 60% diet (χ2 = 28; P < 0.001). While the sample sizes were not large enough for demographic statistics and determination of mortality rates, the diet treatments used in the present experiment had strong effects on the median ages at death across groups.

Figure 3.

Survivorship of female lubber grasshoppers kept on four diet treatments. The late-onset CR group began on a reduced diet at day 50. See Table 1 for further descriptions of diets. The calorie restriction (60%), calorie restriction (70%), and the late-onset CR groups all had greater longevity than the ad libitum group.

Reproductive tactics

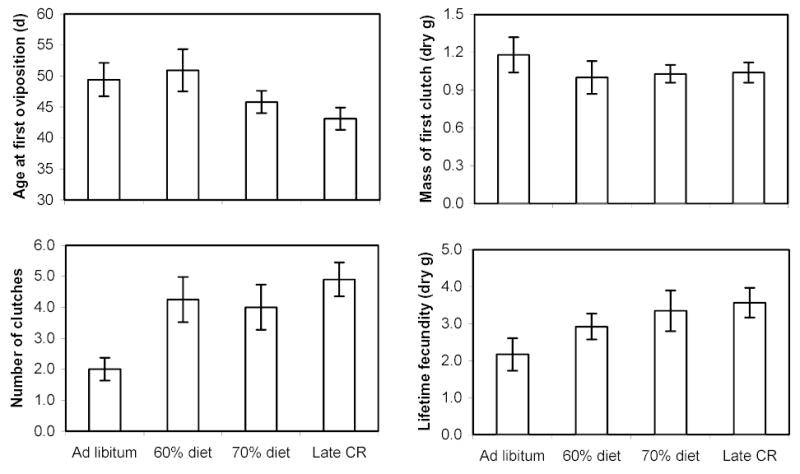

We tested the effects of diet on the age at first oviposition, dry mass of the first clutch, number of clutches, and lifetime fecundity (as cumulative dry mass of eggs laid). Calorie restriction did not delay the age at first oviposition (MANOVA; P = 0.133; F3,37 = 2.00; Fig. 4), reduce the mass of the first clutch (P = 0.846; F3,37 = 0.27), or alter lifetime fecundity (P = 0.133; F3,37 = 2.00). However, CR significantly increased the number of clutches laid (P = 0.007; F3,37 = 4.78). The ad libitum group laid significantly fewer clutches than the late-onset CR group (P = 0.005) and the 60% diet (P = 0.047), but not the 70% diet (P = 0.102).

Figure 4.

Reproductive tactics of female lubber grasshoppers on four diet treatments. See Table 1 for descriptions of diets. Age at first oviposition, mass of first clutch, and lifetime fecundity did not differ across diets. Number of clutches was significantly reduced in the ad libitum group when compared to the 60% diet and late-onset CR.

Hemolymph storage profiles

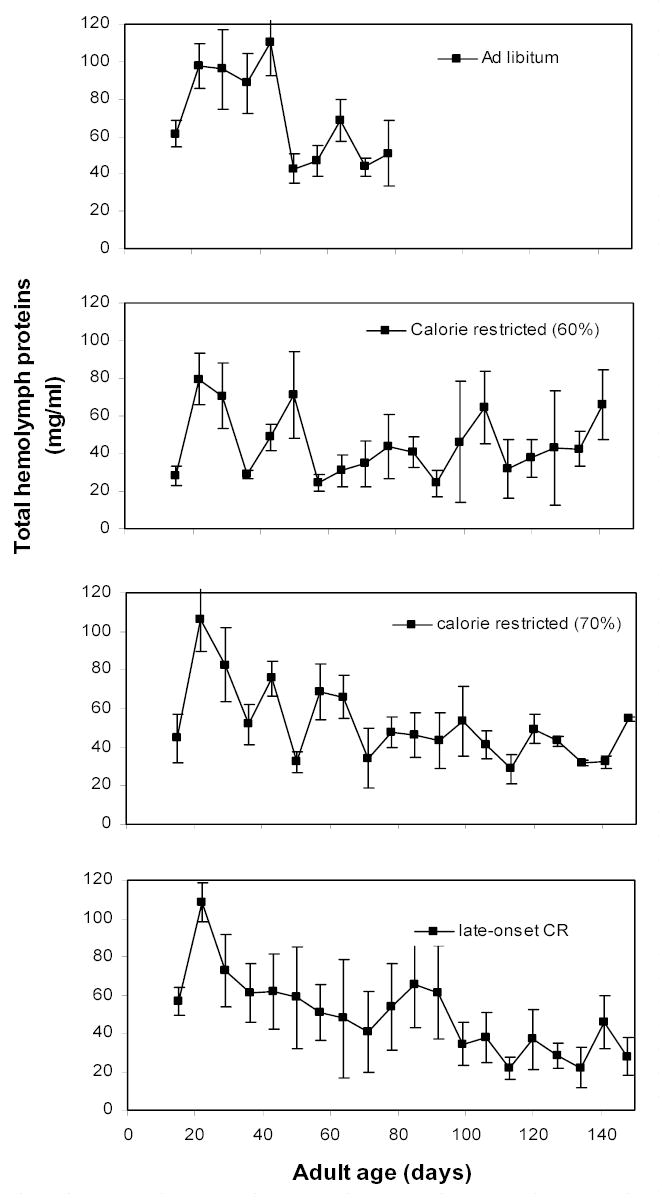

Total hemolymph protein levels were compared across the four diets during the first seven sampling dates (i.e., once weekly from median days 15 to 57), after which samples sizes decreased due to attrition. We used MANOVA, with time as a dependent variable. Sampling age strongly affected the hemolymph protein levels (Fig. 5; Pillai’s Trace; F6,21 = 39.1; P < 0.0001), as has been shown previously (e.g., Hatle et al. 2001). There was also a significant interaction of diet and sampling age (F18,69 = 1.96; P = 0.031), suggesting that the diets responded differently to the passage of time.

Figure 5.

Developmental profiles of total hemolymph protein levels in female grasshoppers kept on four different diets. See Table 1 for descriptions of diets. Total hemolymph proteins serve as an estimate of the main store of proteins in insects. Diets differed little in hemolymph protein levels. The calorie restricted (60%) group had lower protein levels than the ad libitum group on days 36 (P = 0.022) and 43 (P = 0.019). No other comparisons of diets on a specific day were significantly different. In particular, protein levels in the calorie restriction (70%) group never differed from protein levels in the ad libitum group. Data are plotted as median, chronological ages (see Hemolymph samples in Methods for details).

There were only minor differences in total hemolymph protein concentrations among diets on the same sampling day (Fig. 5). Only on days 36 (F3,23 = 4.34; P = 0.017) and 43 (F3,23 = 3.63; P = 0.031) did diet significantly affect protein levels. Specifically, the 60% diet had lower hemolymph protein levels than the ad libitum group on day 36 (P = 0.010) and on day 43 (P = 0.025). Adding day 64 to the model (tested separately because attrition reduced the sample sizes) showed that diet treatments did not effect protein levels on day 64 (F3,19 = 1.00; P = 0.417). No other comparisons of diets on a specific day were significantly different. Because we measured protein concentrations in the hemolymph, and hemolymph volume likely correlates with body mass, these estimates of protein storage are probably adjusted for body size. Remarkably, the ad libitum and 70% diet groups did not differ at any point.

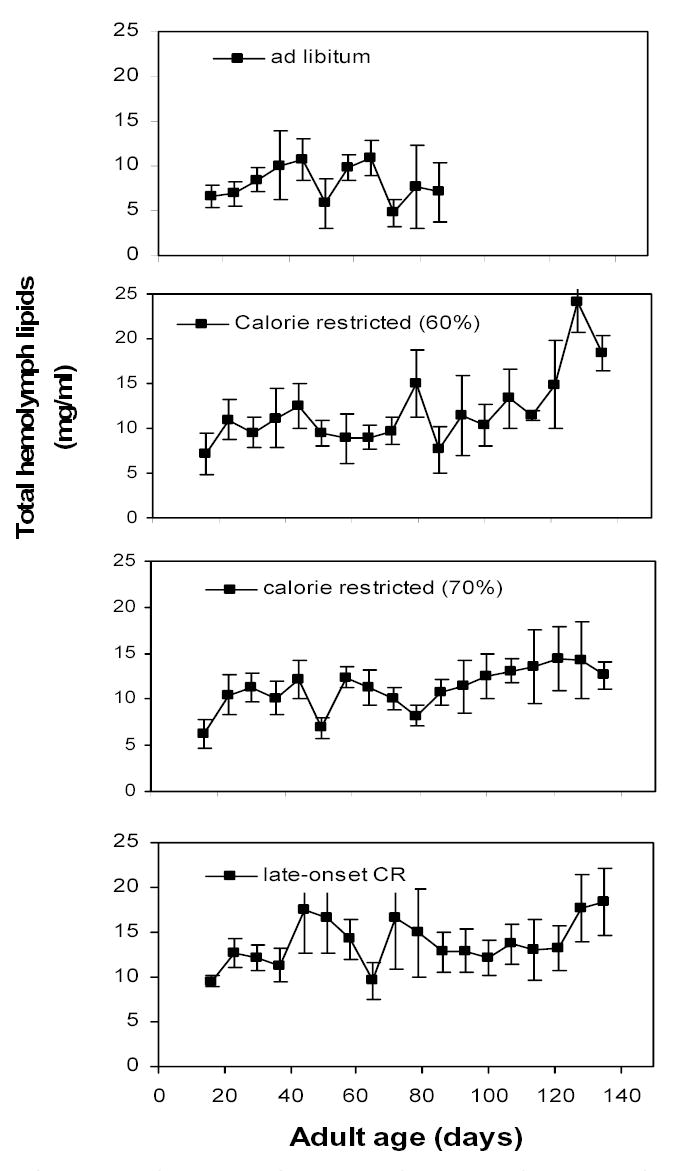

Hemolymph lipids levels rose steadily through the first 57 days in all diets (Fig. 6; MANOVA; Pillai’s Trace; F6,21 = 4.46; P = 0.009). There was no significant interaction of diet and sampling day (F18,69 = 1.58; P = 0.102). Within sampling days, there was only a single statistical difference; on day 50 the late-onset CR group had significantly higher lipid levels than the ad libitum group (P = 0.034). Because the late-onset CR group was fed ad libitum for the first 50 days, this difference is likely an artifact. Adding day 64 to the model (tested separately because attrition reduced the sample sizes) showed that diet treatments did not effect lipid levels on day 64 (F3,21 = 0.33; P = 0.805). No other comparisons of lipid levels across diets were significantly different. Hence, hemolymph lipids do not appear to contribute to the enhanced longevity of grasshoppers on CR.

Figure 6.

Developmental profiles of total hemolymph lipid levels in female grasshoppers kept on four different diets. See Table 1 for descriptions of diets. Hemolymph lipids estimate the amount of lipid transport occurring in an individual, while the fat body is the primary depot for lipids. Diets differed little in hemolymph lipid levels. Data are plotted as median, chronological ages (see Hemolymph samples in Methods for details).

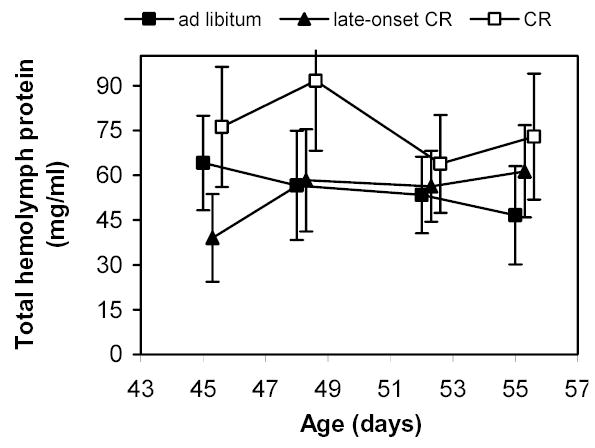

In a separate experiment on total hemolymph protein, we focused more closely on the 10 days surrounding the diet reduction in late-onset CR grasshoppers. In this experiment, there was no effect of age (Fig. 7; MANOVA; Pillai’s Trace F3,31 = 0.59; P = 0.627), no diet effects within ages (all P > 0.30), and no interaction of age and diet (F6,64 = 0.88; P = 0.518).

Figure 7.

Total hemolymph proteins before and after diet reduction at day 50 in late-onset CR female grasshoppers. Total hemolymph proteins serve as an estimate of the main store of proteins in insects. Serial hemolymph samples were collected from grasshoppers on three different diets. Neither chronic- nor late-CR altered hemolymph levels of total proteins. See text for details of diets.

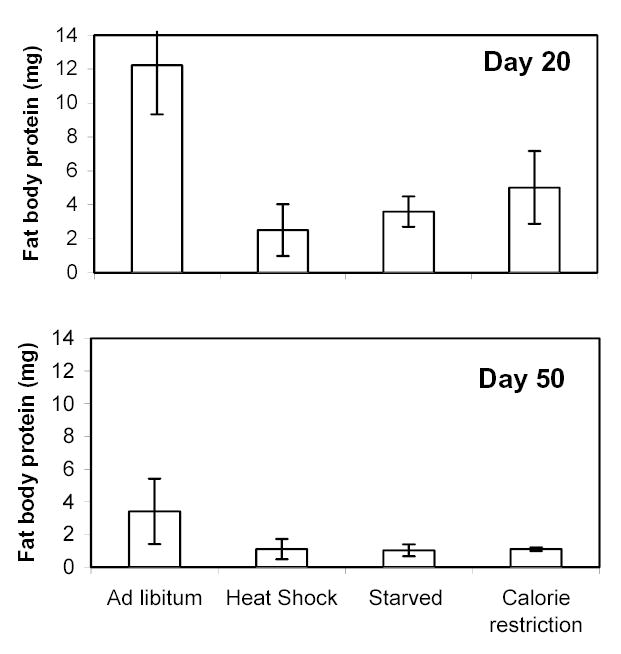

Fat body protein

Total fat body protein is best interpreted as an index of current protein synthesis and therefore future storage. Treatments strongly effected the amount of total fat body protein (Fig. 8; 2-way ANOVA; F7,53 = 6.53; P < 0.0001). Both age (F1,7 = 20.6; P < 0.0001) and diet or temperature (F3,7 = 6.06; P = 0.0014) strongly affected total fat body protein. The interaction did not affect fat body protein (F3,7 = 0.59; P = 0.624). Post-tests (Ryan-Einot-Gabriel-Welsch Multiple Range test) indicated that day 20 grasshoppers had greater fat body protein than the day 50 grasshoppers. Post-tests also indicated that the ad libitum group had greater fat body protein than all three other diet or temperature treatments.

Figure 8.

Total fat body protein of female lubber grasshoppers on diet and temperature treatments. All individuals were fed ad libitum until the treatment date (i.e., day 20 or day 50) and then were subjected to the diet or temperature treatments for 48 h before dissection of fat body. Total fat body protein is best interpreted as an estimate of current protein synthesis, and therefore future protein storage. Day 20 females had higher levels of fat body protein than day 50 females. At day 20, but not at day 50, ad libitum-fed females had higher levels of fat body protein than CR, starved, or heat shocked females. See text for details of diets.

Because we had previously tested the effects of late-onset CR starting at day 50 on longevity (see Fig. 3), this time point was of particular importance. Therefore, to avoid a possible Type I error, we used an ANOVA to directly test whether the ad libitum group had greater fat body protein than the other groups at day 50. When this time point was isolated, the ad libitum group did not have greater fat body protein than other groups (F3,25 = 2.00; P = 0.143).

Discussion and Conclusions

These data do not support the hypothesis that CR or late-onset CR enhance longevity by augmenting protein storage. This study was not a comprehensive analysis of storage but focused on the hemolymph and proteins. Nonetheless, because protein is the limiting resource for phytophagous insects, and the hemolymph is the greatest depot for proteins in insects, the present study suggests that changes in the storage of proteins are not central to the enhanced longevity produced by CR or late-onset CR.

Calorie restriction during the entire adult period, or after day 50 of adulthood, can enhance longevity in female lubber grasshoppers. Median life spans of grasshoppers on 60%, 70%, and late-onset CR diets were 62%, >98%, and 64% longer than ad libitum grasshoppers, respectively. Because of the wealth of previous data on CR slowing aging in other organisms (e.g., Weindruch and Walford 1988; Tatar et al. 2003), the most probable explanation is that CR also slows aging in female lubber grasshoppers.

The conclusion that late-onset CR extends lifespan is slightly weakened by data on body masses. From adult molt through day 50, the ad libitum group and the late-onset CR group were fed identically, and their consumption was identical (see Results, second paragraph). However, the ad libitum group reached a higher maximum weight. Our estimates of body masses are biased by the possible presence of unabsorbed food in the gut, but this bias is unlikely in groups fed identical diets, on a similar schedule. Therefore, the extension of lifespan by late-onset CR should be retested with a larger sample size. This hesitant result does not greatly affect our more important conclusion on protein storage (see below), because protein storage was compared only from days 15 – 57, including only one day on which ad libitum and late-onset CR groups were fed differently.

Calorie restriction typically acts through a trade-off with reproductive output. Lubber grasshoppers have the ability to adjust reproductive output and protein allocation in response to diet; lubbers resorb about 20% of the oocytes when fed ad libitum, and they can resorb up to 75% of their oocytes when on severe CR (~30% of ad libitum, Hatle et al. 2000; Sundberg et al. 2001). However, reproductive tactics early in life in lubber grasshoppers were not altered by life-extending CR (60% and 70% diets). This is consistent with the result that dietary restriction increased lifespan in sterile females of Drosophila (Mair et al. 2004) and the notion that the life extending effects of calorie restriction do not absolutely depend on reducing reproduction. The 60% and 70% diets used in the present study tended to increase the total number of clutches produced. Because age at first oviposition did not differ across the diets used here, this increase in number of clutches appears to be due to the greater lifespan of grasshoppers on CR and continued egg production at older ages, and not due to a higher rate of production of clutches during any given period.

Lubber grasshoppers are univoltine and have an obligate egg diapause as their overwintering stage (Chladny and Whitman 1997; Stauffer and Whitman 1997). In the lab, hatching date seems to be unrelated to oviposition date, as long as temperature is controlled. Because of this, the cumulative number of eggs laid by a female may be more important than the date at which these eggs are laid. If this is true, CR may produce a greater reproductive output. Certainly, living longer in the wild (compared to surviving in the laboratory) has the added challenges of avoiding predation and disease. That said, lubber grasshoppers have an impressive array of chemical and behavioral defenses (Whitman 1990; Hatle et al. 2002), and mark-recapture studies suggest survival in the wild is high (DW Whitman, unpublished data). Further experiments are needed to test whether this reproductive output on CR observed in the laboratory may translate to the wild.

Neither age at first clutch nor size of first clutch were altered by CR. In previous studies with this same species, our colleagues have shown strong effects of diet on age at first clutch and size of first clutch, and their study had smaller samples sizes (n=5) than the present study (Moerhlin and Juliano 1998; see also Hatle et al. 2000, n=8). The low diet used by Moehrlin and Juliano (1998) was 2.0 wet g / day; consumption by grasshoppers fed ad libitum was not measured. In the present study, the 60% diet was 3.3 wet g / day and the 70% diet was 4.0 wet g / day (through age at death for the ad libitum group). These percentages of ad libitum feeding were predetermined, but the actual amount to offer individuals was calculated as the experiment progressed and the feeding rate of ad libitum females was observed. These CR diets significantly increased longevity but did not alter tactics of the first clutch. This interesting result calls for further studies to determine if these patterns of longevity and reproductive output hold in the wild, and whether other storage parameters, such as fat body mass (shown to be most important in reproductive plasticity by Hatle et al. 2006), are affected by these diets.

The most important conclusion of the present paper is that the level of diet reduction needed to extend longevity was not sufficient to reduce protein storage. Grasshoppers on the 70% diet had similar hemolymph protein profiles to the ad libitum group, yet had greater longevity. Results for the 60% diet were similar. More severe food limitation in this grasshopper (30 – 40% of ad libitum) reduced hemolymph protein levels by 40%, without halting reproduction; this result was highly statistically significant and was repeatable across two experiments (Hatle et al. 2001; 2004). That life-extending CR did not alter protein storage is particularly surprising for a phytophagous insect, because they are protein limited during major life history transitions (e.g., Hatle et al. 2003a; Hatle et al. 2006). Hence, the present results do not support the hypothesis that protein storage is involved in life extension by CR.

Late-onset CR grasshoppers also had greater longevity but no alteration in protein storage in comparison to the ad libitum group. This result is due in part to the fact that the ad libitum group reduced hemolymph storage protein during the second clutch (see Fig. 5, top panel, days 50–80). This may be due to the ad libitum group reducing consumption after day 50. As a result, the protein profile of the ad libitum group was similar to the profiles for the CR groups after day 50, despite substantial differences in food availability. Curiously, the natural reduction in consumption by the ad libitum group was appropriately timed but insufficient to extend lifespan.

While the samples sizes used in this paper may seem small to conclude a lack of differences due to treatments, we were clearly able to detect differences in both protein and lipid levels over time. This demonstrates the sufficient sensitivity of our approach and strengthens our conclusion of the lack of effect of life-extending CR on hemolymph protein storage. In addition, we have easily detected significant differences in prior experiments with similar samples sizes (Hatle et al. 2001; n = 8 / group). Previous work has shown it is far better to sample single individuals repeatedly than to sample large numbers of individuals once. For example, hemolymph levels of gonadotropic hormones (i.e., juvenile hormone) and vitellogenin vary 10-fold across individuals of the same age, but the shape of the developmental profiles of these factors is consistent across individuals (cf. Hatle et al. 2000; 2001; 2003a,b; 2004 to Hatle et al. 2006).

The maintenance of protein storage levels while on CR likely comes at the expense of other storage. It may be that grasshoppers on CR are preferentially storing protein, the limiting resource, at the expense of storing other nutrients, such as fat body lipids.

Short-term severe CR reduced total fat body protein levels (i.e., future storage) at day 20, but not day 50, in female grasshoppers. At the same time, late-onset CR started at day 50 was able to extend longevity. This further supports our conclusion that altering storage of ingested proteins is not the mechanism by which CR increases longevity.

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of North Florida’s Undergraduate Academic Enrichment Office and Department of Biology for funding, Doria Bowers, Mike Lentz, and Dan Moon for sharing equipment, Thomas Flatt, Dan Hahn and Doug Whitman for critiquing the manuscript, two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments, Steven Juliano for advice on statistics, and Raime Fronstin and friends for helping acquire experimental animals.

References

- Arking R. Biology of Aging. Sinauer Associates, Inc.; Sunderland, MA, USA.: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Behmer ST, Nes WD. Insect sterol nutrition and physiology: a global overview. Adv Insect Physiol. 2003;31:1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao SX, Dhahbi JM, Mote PL, Spindler SR. Genomic profiling of short- and long-term caloric restriction effects in the liver of aging mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10630–10635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191313598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman RF. The Insects: Structure and Function. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chladny T, Whitman DW. A simple method to culture grasshopper eggs with long egg diapause. J Orthop Res. 1997;6:82. [Google Scholar]

- Dhahbi JM, Kim HJ, Mote PL, Spindler SR. Temporal linkage between the physiologic and genomic responses to caloric restriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5524–5529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305300101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djawdan M, Sugiyama TT, Schlaeger LK, Bradley TJ, Rose MR. Metabolic aspects of the trade-off between fecundity and longevity in Drosophila melanogaster. Physiol Biochem Zool. 1996;69:1176–1195. [Google Scholar]

- Hatle JD, Spring JH. Tests of potential adipokinetic hormone precursor related peptide (APRP) functions: lack of responses. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 1999;42:163–166. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6327(199910)42:2<163::AID-ARCH6>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatle JD, Andrews AL, Crowley MC, Juliano SA. Interpopulation variation in developmental titers of vitellogenin, but not storage protein, in lubber grasshoppers. Physiol Biochem Zool. 2004;77:631–640. doi: 10.1086/420946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatle JD, Borst DW, Eskew ME, Juliano SA. Maximum titers of vitellogenin and total hemolymph protein occur during the canalized phase of grasshopper egg production. Physiol Biochem Zool. 2001;74:885–893. doi: 10.1086/324475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatle JD, Borst DW, Juliano SA. Plasticity and canalization in the control of reproduction in the lubber grasshopper. Integ Comp Biol. 2003a;43:635–645. doi: 10.1093/icb/43.5.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatle JD, Juliano SA, Borst DW. Juvenile hormone is a marker of the onset of canalized reproduction in lubber grasshoppers. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;30:821–827. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(00)00054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatle JD, Juliano SA, Borst DW. Hemolymph ecdysteroids do not affect vitellogenesis in the lubber grasshopper. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 2003b;52:45–57. doi: 10.1002/arch.10067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatle JD, Salazar BA, Whitman DW. Survival advantage of sluggish individuals in aggregations of aposematic prey, during encounters with ambush predators. Evol Ecol. 2002;16:415–431. [Google Scholar]

- Hatle JD, Waskey TJ, Juliano SA. Plasticity of grasshopper vitellogenin production in response to diet is primarily a result of changes in fat body mass. J Comp Physiol B. 2006;176:27–34. doi: 10.1007/s00360-005-0028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haunerland NH. Insect storage proteins: gene families and receptors. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;26:755–76. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(96)00035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano SA, Olson JR, Tillman EG, Hatle JD. Plasticity and canalization of insect reproduction: Testing alternative models of life history transitions. Ecology. 2004;85:2986–2996. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood TBL. Immortality of the germ-line versus the disposability of the soma. In: Finch CE, Schneider EL, editors. Handbook of the Biology of Aging. 2nd ed. Van Nostrand Reinhold; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood TBL. Evolution of ageing. Mech Age Dev. 2002;123:737–745. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00419-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo VD, Finch CE. Evolutionary medicine: from dwarf model systems to healthy centenarian? Science. 2003;299:1342–1346. doi: 10.1126/science.1077991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mair W, Goymer P, Pletcher SD, Partridge L. Demography of dietary restriction and death in Drosophila. Science. 2003;301:1731–1733. doi: 10.1126/science.1086016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mair W, Sgrò CM, Johnson AP, Chapman T, Partridge L. Lifespan extension by dietary restriction in female Drosophila melanogaster is not caused by a reduction in vitellogenesis or ovarian activity. Experimental Gerontology. 2004;39:1011–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marieb EN. Anatomy and Physiology. 2nd ed. Benjamin Cummings; San Francisco: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mefferd CL, Hatch W, Burries RL, Whitman DW. Plasticity in the length of the ovulation-oviposition interval in the lubber grasshopper Romalea microptera. J Orthop Res. 2005;14:31–32. [Google Scholar]

- Moerhlin GS, Juliano SA. Plasticity of insect reproduction: testing models of flexible and fixed development in response to different growth rates. Oecologia. 1998;115:492–500. doi: 10.1007/s004420050546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhout HF. Insect Hormones Princeton University Press; Princeton: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pugh TD, Oberley TD, Weindruch R. Dietary intervention at middle age: caloric restriction but not dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate increases lifespan and lifetime cancer incidence in mice. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1642–1648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose MR. Evolutionary Biology of Aging. Oxford University Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT User's Guide, Version 8, Volumes 1–5. SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC, USA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons FH, Bradley TJ. An analysis of resource allocation in response to dietary yeast in Drosophila melanogaster. J Insect Physiol. 1997;43:779–788. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(97)00037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer TW, Whitman DW. Grasshopper oviposition. In: Gangwere S, editor. The Bionomics of Grasshoppers. CABI; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg SV, Luong-Skovmand MH, Whitman DW. Morphology and development of oocyte and follicle resorption bodies in the lubber grasshopper, Romalea microptera (Beauvois) J Orthop Res. 2001;10:39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Tatar M, Kopelman A, Epstein D, Tu MP, Yin CM, Garofalo RS. A mutant Drosophila insulin receptor homolog that extends life-span and impairs neuroendocrine function. Science. 2001;292:107–110. doi: 10.1126/science.1057987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatar M, Bartke A, Antebi A. The endocrine regulation of aging by insulin-like signals. Science. 2003;299:1346–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1081447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker MP, Lewis CJ, Whitman DW. Effects of males on the fecundity and fertility of female Romalea microptera grasshoppers. J Orthop Res. 1999;8:277–283. [Google Scholar]

- Weindruch R, Walford RL. The retardation of aging and disease by dietary restriction. Charles C. Thompson; Springfield, IL, USA: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Whitman DW. Grasshopper chemical communication. In: Chapman R, Joern A, editors. Biology of Grasshoppers. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1990. pp. 357–391. [Google Scholar]