Cancer treatment has been based on the implicit assumption that human cancer populations are homogeneous. According to this model, every cell in a tumour has equal tumorigenic potential, the culmination of a Darwinian process that selects for an increasingly tumorigenic phenotype. Genetic dissection of the oncogenic process has provided a satisfying molecular explanation of this evolutionary phenomenon: there is now compelling evidence that cancer is a multistage process involving the accumulation of genetic and epigenetic changes in genes involved in the regulation of cell growth, DNA repair and metastasis. These molecular and cellular perspectives on oncogenesis are supported by elegant experiments carried out by Philip Fialkow and his colleagues in the 1960s and 1970s that demonstrated that cancer cell populations as they present in the clinic are clonal; that is, they are all descended from a single cell, presumably as the culmination of a rigorous evolutionary selection.

Modern strategies for cancer drug development therefore follow from these 2 powerful paradigms: First, as cancer populations are apparently homogeneous and clonal, the most successful cancer treatments will be those that kill the largest number of cells in the tumour. And second, the most powerful and least toxic treatments will be those that exploit the molecular differences between tumour cells and their normal counterparts.

Recent experiments, however, much of it led by Canadian researchers, suggest that human tumours may not in fact be functionally homogeneous and that only a very small percentage of cells in a tumour actually have true tumorigenic potential. It follows that these cells, so-called cancer stems cells, should be the targets for drug development, not the vast majority of cells in the tumour that are merely the nontumorigenic daughter cells of cancer stem cells.1

Much of our current thinking about stem cells come from research on the cellular organization of the hematopoietic and immune systems. Landmark research initiated by Till and McCulloch in the 1960s in Toronto demonstrated that all of our blood and immune cells arise from a common hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) in the bone marrow.2 The HSC is present at a frequency of about 1 in 10 000 cells and can be functionally distinguished from the vast majority of hematopoietic cells by 2 defining characteristics: the unique ability to self-renew (i.e., to give rise to more stem cells) and the ability to divide and differentiate into large numbers of mature, differentiated progeny.

Stem cells with similar properties have now been identified in the brain, gut, mesenchynal skin tissue, breast and prostate.

If our tissues are organized into stem cell hierarchies ranging from stem cells with extensive proliferative and self-renewal capacity to mature cells with little or no capacity for cell division, it is not a great leap to imagine that cancer cell populations might also be organized in stem cell hierarchies, ranging from a small number of cells that are responsible for fuelling the uncontrolled growth of the tumour and the daughter, largely nondividing cells.

Experimental evidence for this hypothesis slowly accumulated in the last century and has accelerated over the past 5 years with recent reports on human leukemias, CNS tumours, breast cancer, multiple myeloma, and prostate and, most recently, colon cancer.1,3 Again Canadian researchers, including John Dick1 and Peter Dirks,4,5 have been pioneers in this exciting area of cancer research.

The implications of a stem cell model for human cancer are significant. If this view of human cancer continues to gain experimental support, it is likely that our current strategies may have emphasized the wrong cells. We have targeted therapy to the bulk of the cells in the tumour — the pawns. But to win the cancer game, this model suggests we have to reorient our energies to capturing the King — the rare stem cells in a tumour.

How can this be accomplished? Again, the study of normal HSCs is instructive. Based on work by Irv Weissman at Stanford, we know that the biological differences between HSCs and their differentiated progency are the result of differences in the expression of a small number of cell-surface markers (and other proteins). These molecular differences can be exploited to isolate and characterize essentially pure populations of HSCs.

It seems not unreasonable to suggest that the differences in biological properties of cancer stem cells and the bulk of a tumour also are accompanied by changes in gene expression and that these changes can be exploited to purify cancer stem cells.

Once purified, these calls can be characterized in the most intimate detail, by the modern tools of gene expression profiling and informatics. The ultimate goal of this exercise would be both to understand what makes cancer stem cells do what they do, but also to use this information to design drugs that will truly target the King by disrupting the molecular pathways that are altered in cancer stem cells.

Now that the true cellular targets are in our sights, the convergence of many experimental approaches — stem cell biology, functional genomics, combinational chemistry, imaging technologies and clinical trials — promises to herald an important new era in cancer research and treatment. There are several lessons to be learned from this still unfolding story: First, the importance of excellence, time and fundamental research. Second, the importance of an environment that values and encourages young talent. Many of those who have contributed to this research are direct descendants of Till and McCulloch (e.g., John Dick who trained with the author, who in turn trained with Jim Till). Third, the importance of critical mass. As noted above, future progress in this area will likely depend on a variety of disparate disciplines, working as a team. Fourth, the importance of a strong cadre of clinician scientists who serve as the essential link between fundamental science and clinical application. Fifth, the recognition that clinical research is not simply bench to bedside. Rather, it is bedside to bench to bedside to bench to bedside.

And finally, the cancer stem cell story beautifully illustrates the centrality of research to the understanding of human health and disease. From this understanding, new opportunities are unfolding that hold great promise for translating understanding into entirely new approaches to therapy.

Alan Bernstein President Canadian Institutes of Health Research Ottawa, Ont.

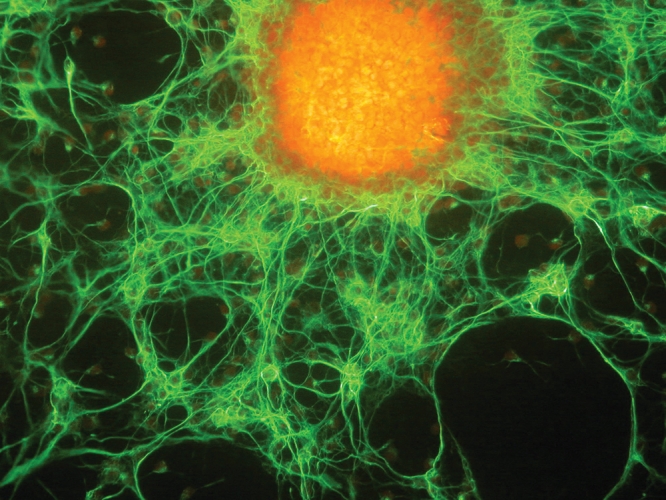

Figure. Mouse neural stem cell. Photo by: Image courtesy of R. Erickson, I. Nakano and H.I. Kornblum, Neural Stem Cell Research Center

Footnotes

Published at www.cmaj.ca on Dec. 13, 2006.

Competing interests: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.O'brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, Dick JE. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature 2006; DOI: 10.1038/nature05372. Epub 2006 Jul 27 ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.McCulloch EA, Till JE. Perspectives on the properties of stem cells [review]. Nat Med 2005;11:1026-8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, et al. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer– initiating cells. Nature. DOI:10.1038/nature05384. Epub 2006 Nov 19 ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Dirks PB. Stem cells and brain tumours. Nature 2006;444:687-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Dirks PB. Brain tumor stem cells [review]. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2005;11(2 Suppl 2):12-3. [DOI] [PubMed]