Abstract

Dyadic physical aggression in the relationships of 158 young, at-risk couples was examined as a predictor of relationship separation over the course of 6 years. A high prevalence of physical aggression and a high rate of separation were found, with 80% of couples engaging in physical aggression (as reported by either partner or as observed) and 62% separating over time. As predicted, physical aggression significantly increased the likelihood of relationship dissolution even after accounting for psychological aggression, prior relationship satisfaction, and relationship contextual factors (length of relationship, relationship type, and children in the household). Of the contextual factors, relationship type was predictive of relationship dissolution: married couples were least likely to dissolve their relationships compared to cohabiting and dating couples.

Keywords: physical aggression, psychological aggression, relationship satisfaction, relationship separation

Relationship Separation for Young, At-Risk Couples: Prediction from Dyadic Aggression

Physical aggression in couples is associated with poor relationship outcomes, including low relationship satisfaction and high relationship instability. For newly married couples, aggression is associated with lower marital satisfaction and a greater likelihood of separation later in their relationships (DeMaris, 2000; Rogge & Bradbury, 1999; Testa & Leonard, 2001). In one study (Lawrence & Bradbury, 2001), 70% of new marriages involving aggression were considered failed within 4 years, as indexed by dissatisfaction or separation/divorce compared to 38% of nonaggressive marriages, and the severity of the dyadic physical aggression greatly increased the likelihood of failure years later. These longitudinal studies of newlywed couples shed important light on the adverse effects of aggression on marital adjustment. However, findings from these studies have limited generalizability, because these studies were often based on nonrepresentative samples involving news advertising, low recruitment rates, and restricted sample design (e.g., excluding couples with children prior to marriage).

The possible influence of aggression on the longitudinal course of intimate relationships among couples with lower socioeconomic backgrounds has been less examined. Limited studies have indicated that young couples from lower socioeconomic status are more likely to experience higher rates of mutual aggression (Capaldi & Crosby, 1997) and to cohabit with children before marriage (Pears, Pierce, Kim, Capaldi, & Owen, 2005; White & Rogers, 2000). It is possible that couples from deprived backgrounds with fewer resources follow developmental pathways of aggression and relationship adjustment with differing implications for the impact of aggression. Given that low socioeconomic status populations have been underrepresented in research on couples (Karney & Bradbury, 1995), investigating the role of aggression among young couples with such backgrounds has theoretical and clinical significance.

The present study aimed to overcome the limitations in the extant studies and extend our understanding of aggression and the course of intimate relationships by examining young couples from a community sample with at-risk (by virtue of living in neighborhoods with relatively high rates of delinquency) and low socioeconomic backgrounds. The present study, unlike many earlier descriptive studies, sought to contribute to the field by employing a specific theoretical model that helps to understand the role of aggression and the course of couples relationships. Based on a dynamic developmental-systems perspective, we examined the relative influence of aggression (both physical and psychological), contextual factors, and relationship satisfaction on relationship stability.

The dynamic developmental-systems perspective conceptualizes behavior in couples as inherently interactive and responsive to developmental characteristics of each partner and to both broader and more proximal contextual factors (Capaldi, Shortt, & Kim, 2005). This framework was originally developed to explain developmental risks and the course of aggression over time, but it can also provide a framework to examine the effects of aggression on the course of relationship outcomes. The main emphasis of this approach is on the nature of the relationship itself, primarily the interaction patterns within the dyad as they are initially established and as they change over time, as well as proximal contextual factors affecting the interaction patterns. In addition, the dynamic developmental-systems perspective views personal characteristics and intrapersonal processes of both partners as important to a couple’s adjustment. In the present study, we considered (a) contextual factors such as length of relationship, relationship type, and presence of children; (b) the aggressive interaction patterns of the couple (i.e., physical and psychological aggression); and (c) intrapersonal processes (i.e., cognitive appraisals of the relationship assessed as relationship satisfaction).

Prior studies predicting to relationship breakdown frequently did not examine – or control for – key aspects of the relationship context, such as prior length of relationship or presence of children. In newlywed couples, it may be assumed that the couples start relatively equal at marriage for such factors, but relationship length prior to marriage varies considerably, and children are often born prior to marriage, especially in higher risk samples (Pears et al., 2005). Further, cohabitation prior to marriage is much more frequent than in previous cohorts. Thus, to adequately understand adult experiences of relationship aggression and its impacts, study designs that embrace these differing contextual circumstances are needed. A few studies have indicated that longer relationship durations among young couples are associated with higher levels of aggression (Capaldi, Shortt, & Crosby, 2003). Further, the risk of relationship dissolution varies depending on the duration of the relationship; divorce is most common within the first 4 years of marriage (Rogge & Bradbury, 1999). Similarly, cohabitation has been associated with high rates of physical aggression (Stets, 1991), relationship instability, negative problem-solving behavior, and less support (Cohan & Kleinbaum, 2002). Sharing a household in a cohabiting or marital relationship has been associated with higher levels of psychological aggression in young couples (Capaldi et al., 2003). In addition, becoming parents has been described as a normative event that involves many changes for the couple (e.g., Cowan & Cowan, 1992). Whereas having children together can increase the stability of the marriage, children can also decrease relationship satisfaction (e.g., Belsky, Spanier, & Rovine, 1983).

Regarding aggressive interaction patterns, a number of longitudinal studies have examined the association between aggression and marital outcomes. Heyman, O’Leary, and Jouriles (1995) found that wives who experienced premarital husband-to-wife physical aggression were more likely to take steps toward divorce than wives who had not experienced such aggression. Rogge and Bradbury (1999) also found that presence of dyadic physical aggression in early marriage significantly predicted marital dissolution after 4 years of marriage. In addition, psychological aggression has been found to precede incidents of physical aggression in engaged couples (Murphy & O’Leary, 1989), and verbal aggression predicted physical aggression and lower marital satisfaction 1–2 years later in a large sample of couples applying for marriage licenses (Schumacher & Leonard, 2005). Although few studies have examined the relative contribution of different types of aggression to relationship dissolution, it has been suggested that psychological aggression has as great as, or even greater, impact on victims compared to physical aggression (O’Leary, 1999). In fact, Marshall (1999) found that men’s subtle psychological aggression had stronger and more consistent association with women’s self-esteem, coping behavior, perceived physical health, psychological symptoms, and relationship perceptions than did overt psychological, physical, and sexual aggression.

It is possible that, as Rogge and Bradbury (1999) suggested, physical aggression could rapidly accelerate aversive cycles in the dyad, or alternatively, it could be the case that couples with lower socioeconomic at-risk backgrounds have higher tolerance for both psychological and physical aggression; thus, aggression has limited predictive power for relationship stability. Given that there is little research on the role of aggressive behavior in the developmental course of intimate relationship among young couples at risk, examination of the relative importance of psychological and physical aggression for relationship instability is critical for intervention programs to help reduce violence and enhance relationship stability.

The role of intrapersonal process in couples’ relationships has frequently been examined via individual’s appraisals of relationship satisfaction. A number of studies have indicated that relationship satisfaction is closely related to aggression (e.g., O’Leary et al., 1989; Rogge & Bradbury, 1999) and also to relationship outcomes (e.g., Huston, Caughlin, Houts, Smith, & George, 2001). Relationship satisfaction has often been studied as a separate relationship outcome (Kurdek, 2002); however, from the dynamic developmental-systems perspective, how couples view their partner and the relationship is an important feedback loop that is also influenced by several factors other than aggression (e.g., financial situation, social support, number of children). Therefore, ignoring this variable would result in overrepresentation of the importance of aggression or other contextual variables in the course of the relationship. In the present study, we examined to what extent couples view of their partner and the relationship would be predictive of relationship outcomes when considered along with aggression.

Present Study

We hypothesized that physical aggression would be predictive of separation over time for young, at-risk couples in this community sample. The influence of physical aggression on relationship dissolution was examined in the context of psychological aggression and relationship satisfaction. Although we anticipated that levels of physical and psychological aggression would be associated with each other, physical aggression was expected to be corrosive over time and salient for dissolution (Rogge & Bradbury, 1999). Low relationship satisfaction was expected to predict separation, but we expected separation to be predicted by physical aggression in addition to relationship satisfaction.

Prediction models also included relationship contextual factors including (a) duration or length of relationship; (b) relationship type or whether the couple was dating, living together, or married; (c) whether the couple had children (biological or step) in the household. Relationship aggression was primarily expected to account for the association of the contextual factors with relationship dissolution, as the dynamic developmental-systems theory views the impacts of contextual factors on relationship outcomes as largely mediated by relationship processes.

The sample included a range of severity and frequency of aggression. In prior work with the current sample, couples with high frequency aggression in the range of shelter samples were identified (Capaldi & Owen, 2001). We opted to use the entire behavioral distribution of dyadic aggression and not assign the couples to types according to the severity or frequency of aggression. Using continuous measures such as construct scores maximizes power to detect effects and allows for the inclusion of information on both frequency and level or severity of aggression. This decision also reflects the developmental-systems approach in which aggression toward a partner was viewed as a dynamic, relationship process that develops over time, with distinctions between severity or frequency of aggression regarded as one of degree rather than type (Capaldi & Kim, 2005).

Method

Participants were part of the Oregon Youth Study (OYS), a longitudinal study of 206 boys at risk for juvenile delinquency and their families. This community sample was recruited from randomly selected public schools located in neighborhoods with a higher than usual incidence of juvenile delinquency for a medium-sized metropolitan area in the Pacific Northwest. The sampling design was such that the boys had an elevated risk for delinquency (as indexed by the neighborhood). All boys in Grade 4 were invited to participate across a 2-year span to form two cohorts of families. After an initial introduction letter from the school, families were removed from the list if they did not want to be contacted by study staff. The remaining families received a phone call, followed by a home visit to explain the study. The recruitment rate was 74%. Although the majority of the boys did not have conduct problems in Grade 4, over one half of the boys were arrested by young adulthood. The participants were largely European American (90%) and from families that were lower and working class (75%). Participants were compensated for their time. Participation rates in late adolescence and young adulthood averaged about 98%.

Procedure

When the boys were in young adulthood (average age was 21 years, with ages ranging from 20 to 24 years), 158 of them participated in a couple’s assessment (Time 1, T1) with a female romantic partner (average age was 21 years, with ages ranging from 16 to 42 years). The couple’s assessment included interviews, questionnaires, and videotaped discussions. The discussions were 34 minutes in length and included problem solving on topics chosen by each partner. The couple was seated comfortably in chairs close together so that they could touch. The couples completed another couple’s assessment at about 3 years (Time 2, T2) and about 6 years after the initial visit (Time 3, T3). At T2, 50% of the 158 couples were no longer together. At T3, 62% of the 158 couples had separated and 38% were intact.

Safety procedures

The discussion tasks were designed to elicit problem-solving discussions, rather than to cause heated conflict. For example, each partner chose a topic on his/her own from a list that included potentially neutral issues (e.g., where to go on dates) as well as more emotive issues (e.g., your partner puts you down in front of your friends). Couples could also choose a topic not on the list. Project staff were instructed to halt any discussions in which either participant might sustain an injury. A clinical psychologist was available for consultation. Following the discussions, the man and woman were briefly interviewed in separate rooms about how the task went for them, and each was asked if their partner did anything that they did not like during the discussions. None mentioned physical aggression in response to this question. Thus, participation in the discussions did not appear to cause undue distress for the couples. Should that have happened, staff would have brought in the clinical psychologist to meet with the participant, evaluate the situation, and provide assistance in ensuring the participant’s safety. A list of referrals to counseling, including programs dealing with domestic violence, was available to participants upon request.

Measures

The videotaped discussions at the initial T1 and follow-up T2 visits were coded with the Family and Peer Process Code (FPPC; Stubbs, Crosby, Forgatch, & Capaldi, 1998). Coders were research staff who participated in a 3-month training to learn the code and establish reliability. When coding the interactions, the coders assigned each behavior to 1 of 24 interpersonal positive, negative, and neutral content codes and 1 of 6 affective ratings from positive to negative affect. Two observers independently coded a randomly selected 15% of interactions. Coder reliability was regularly monitored. The overall content kappa was .75 and the overall affect kappa was .73 at T1, and the overall content kappa was .76 and the affect kappa was .81 at T2.

Relationship Aggression

To form aggression constructs, indicators for each construct were identified using data from the couples questionnaires, interviews, and observed interactions. Items comprising an indicator or scale needed to be internally consistent or produce an alpha of .6 or higher and an item-total correlation of .2 with a significance level of .05 or better. Indicators or scales were required to converge with the other indicators intended to measure the construct. Indicators were standardized (0–3 scale for physical aggression and 1–5 scale for psychological aggression) and then averaged to produce construct scores.

Physical aggression

The physical aggression construct included self- and partner reports as well as observational data. Observed physical aggression as defined in the FPPC included any aversive physical contact and ranged from light hitting and pinching to punching and slapping. Only aversive physical contact coded in neutral, distressed, hostile, or sad affect was included, excluding physical aggression in positive affect. Rate per minute was used as an index of the frequency of aggression. Kappa for the physical aggression cluster was .65 at T1 and .56 at T2. After viewing and coding the interactions, coders also completed ratings to get the impression of a cultural expert on the behaviors displayed during the interactions. Each partner was rated on the occurrence (yes versus no) of moderate physical aggression (e.g., “participant pushed, grabbed, slapped partner during taping”) and severe physical aggression (e.g., “participant kicked, bit, or hit partner with fist”) and whether there were indications of such behaviors in the past with partner. The coder ratings asked about similar aggressive behavior as indicators of the reported measure (e.g., the Conflict Tactics Scale, Straus, 1979; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). The correlations between the coded physical aggression and the coder ratings ranged from .49 to .59 for men and women across T1 and T2. The coder ratings were combined with the rate per minute of coded physical aggression to create one score from the couple interactions.

Other indicators included self-reported and partner reported items from: (a) interview that solicited detailed information about any physical aggressive behavior occurring in the past year e.g., “How many times has your partner hurt you”; (b) Conflict Tactics Scales – Original Version (Straus, 1979) and Revised Version (Straus et al., 1996; e.g., “How often did your partner hit or tried to hit you with something hard?”); (c) Adjustment with Partner – Short Form (from the National Survey of Health and Stress; Kessler, 1990; e.g., “When you and your partner have a disagreement, how often does your partner push, grab, or shove?”); and (d) Dyadic Social Skills Questionnaire (Capaldi, 1994; “Would you say that when you are with your partner, your partner hurts you, e.g., hits or twists your arm?”). Scale alphas ranged from .46 to .83 for men and women across T1 and T2. The correlations between self-report and partner report for his and her physical aggression ranged from .31 to .40 across T1 and T2.

Regarding the physical aggression construct, it was not possible to strictly adhere to the guiding principles of construct building, as using alpha criteria of .6 would have resulted in acts of physical aggression inappropriately being excluded from the construct. It is not necessarily the case that if one type of physical aggression is present for a couple (e.g., punching) that another is likely to be present (e.g., hitting with an object), although there is no doubt that these two behaviors are both acts of physical aggression. The correlations between men’s and women’s physical aggression construct scores were r (158) = .70, p < .001 at T1 and r (79) = .57, p < .001 at T2, respectively; thus, the scores were combined to create dyadic level of physical aggression. As the observed physical aggression was taken from a relatively short sample of the couples’ behaviors, there was relatively low, although significant, convergence between observed and the reported measure of physical aggression, r (157) = .17, p < .05 at T1 and r (79) = .35, p < .01 at T2. Since each indicator of physical aggression was considered significant and worthy of inclusion in the physical aggression construct, none were dropped.

At T1, the construct scores comprised of observed and reported data identified 80% of 158 couples as having physical aggression in their relationships. Of these 126 aggressive couples, 37% both reported and were observed using physical aggression, 43% reported but were not observed using physical aggression, and 20% were observed but did not report using physical aggression. At T2, the construct scores indicated that 73% of 79 couples that remained intact had some physical aggression in their relationships. Of these 58 aggressive couples, 41% both reported and were observed using physical aggression, 43% reported but were not observed using physical aggression, and 16% were observed but did not report using physical aggression.

Psychological aggression

Indicators for psychological aggression paralleled those for physical aggression and came from observational data and couples questionnaires/interviews. Observed psychological aggression was the rate per minute of content codes negative verbal, verbal attack, and coerce during the problem-solving task. Negative verbal behavior was blaming or disapproving of the partner (e.g., “You really blew that one, didn’t you.”). Verbal attack included name-calling, threats, and humiliation of the partner (e.g., “You’re such a loser.”). Coerce was a demand for behavior change that implied impending physical or psychological harm (e.g., “You’ll shut up if you know what is good for you.”). As with physical aggression, only behaviors coupled with neutral or negative affects were included. Kappa for the psychological aggression cluster was .69 for T1 and .69 at T2. Coders also completed ratings on the occurrence of psychological aggression as was done for physical aggression. The correlations between the coded psychological aggression and the coder ratings ranged from .51 to .62 for men and women across T1 and T2. The coder ratings were combined with the rate per minute of coded psychological aggression to create one score from the couple interactions.

As for physical aggression, both the man and the woman reported on: (a) any psychologically aggressive behavior occurring in the past year between the couple via the interview (e.g., “Did arguments/fights involve your partner name calling, yelling, threats, sulking, or refusing to talk, screaming or cursing, throwing/breaking something not at partner?”); (b) Conflict Tactics Scales – Original Version (Straus, 1979) and Revised Version (Straus et al., 1996; e.g., “How often did your partner yell and/or insult?); (c) Dyadic Social Skills Questionnaire (Capaldi, 1994; e.g., “Would you say that your partner tries to put you down?”); (d) Adjustment with Partner – Short Form (from the National Survey of Health and Stress; Kessler, 1990; e.g., “When you and your partner have a disagreement, how often did your partner insult or swear, sulk or refuse to talk?”); and (e) Partner Interaction Questionnaire (Capaldi, 1991; e.g., “How often has your partner made you feel bad by the things s/he says to you?”). Scale alphas ranged from .80 to .89 for men and women across T1 and T2. The correlations between self-report and partner report for his and her physical aggression ranged from .45 to .54 across T1 and T2. Correlations between observed psychological aggression and reported psychological aggression were r (157) = .50, p < .001 at T1 and r (79) = .35, p < .01 at T2. Similar to physical aggression, psychological aggression scores for the men and women were highly associated, r (158) = .85, p < .001, and r (79) = .77, p < .001 at T1 and T2, respectively, and thus were combined to create index scores of dyadic level of psychological aggression within the dyad.

Contextual Factors

Length of relationship, relationship type, and children in the household

In the couples’ interview, both partners reported on their length of relationship, relationship type, and children in the household. Length of relationship was computed by taking the mean of men and women’s reports. The mean length of relationship was 82.88 weeks, SD = 73.71, range from 4.4 to 364 weeks. Couples reported on whether they were dating, cohabiting, or married. Exploratory analyses established that these relationship types showed a linear association with the outcome of relationship dissolution, with dating couples the most likely and married couples the least likely to separate. Therefore, this variable was coded 1 for dating, 2 for cohabiting, and 3 for married. At T1, 45% of the couples were dating, 37% cohabiting, and 18% married. At T2, 15% of the couples were dating, 32% cohabiting, and 53% married. The children in the household variable was coded 0 for no children and 1 for any children in the household (30% at T1 and 61% at T2).

Relationship satisfaction

Both partners reported on their relationship satisfaction using the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976). The Cronbach alpha for the scale for men and women respectively was .93 and .87 at T1 and .93 and .92 at T2. Men and women’s relationship satisfaction constructs were strongly associated, r (158) = .51, p < .001 at T1 and r (79) = .65, p < .001 at T2; therefore, they were combined to create index scores of dyadic relationship satisfaction.

Analytic Plan

An event history or survival analysis was conducted to predict relationship separation from aggression, contextual factors, and satisfaction and to model the likelihood of the event of dissolution. Thirty-eight percent of the couples did not experience relationship dissolution during the time period of the current study and were right censored. Event history analysis can accommodate such right-censored data and maximize power to detect effects by including both censored and noncensored data. Although large amounts of censoring (i.e., more than one half the sample, which is not the case in this sample) can also reduce power, were the censored data not accounted for in the analysis, estimates of time to relationship dissolution would be biased downward. Event history analysis estimates survival probabilities (i.e., proportions of couples that did not experience relationship dissolution through each successive time period) and hazard probabilities (i.e., proportions of couples still at risk who experienced relationship dissolution at each time period). The possible longest survival time was 6 years, and interval of survival time was set to 1 year.

In the present study, a discrete approach to event history analyses was used to determine the effects of (a) time in years, (b) time-invariant and time-variant predictors, (c) interactions between time and the predictors (i.e., to test whether the effects of predictors on risk for separation were constant or vary over time), and (d) power terms of the predictors. These last two were done to test assumptions of proportionality and linearity, both of which were met. Neither nonlinear effects of the predictors nor interactions between time and the predictors were expected, but it was necessary to test them in order to estimate the models adequately. A person-period data set was created with a separate case for each couple for each wave in which they participated, and a set of dummy variables was created to identify the year of participation for each couple (because waves spanned 2–3 years). The dependent variable was a dichotomous score indicating whether the couple did or did not separate in that year. Once a couple separated, they no longer contributed records to the dataset for future years.

The time-invariant predictor was length of relationship in weeks obtained at T1. The time-varying predictors were levels of physical and psychological aggression and relationship satisfaction, relationship type, and children in the household. Using all available data, for couples that separated by T2, T1 scores were used for the time-varying predictors. For couples that did not separate until T3 and intact couples, T1 and T2 scores were used for the time-varying predictors.

Results

Correlational Analyses

As a first step, associations among predictor constructs were examined for T1 and T2. Physical aggression was positively associated with psychological aggression at T1, r (158) = .58, p < .001, and T2, r (79) = .49, p < .001. Psychological aggression was negatively associated with relationship satisfaction at both time points, r (158) = −.45, p < .001 and r (79) = −.70, p < .001. Physical aggression was negatively associated with relationship satisfaction at T2 only, r (79) = −.27, p < .05. Regarding relationship contextual factors, relationship duration was positively associated with relationship type (dating, cohabiting, married) at T1, r (158) = .32, p < .001, and children in the household at T1 and T2, r (158) = .44, p < .001 and r (79) = .38, p < .001. Relationship type was positively associated with children in the household at both time points, r (158) = .39, p < .001 and r (79) = .27, p < .05. Physical and psychological aggression were positively associated with length of relationship at T1, r (158) = .18, p < .05 and r (158) = .20, p < .05, and children in the household at T1, r (158) = .26, p < .001 and r (158) = .25, p > 001, and T2, r (79) = .25, p < .05 and r (79) = .28, p < .05. For couples at T1, relationship type was positively associated with psychological aggression, r (158) = .33, p < .001. At both time points, couples’ relationship type was positively associated with relationship satisfaction, r (158) = .20, p < .05 and r (79) .36, p < .001.

Discrete Event History Analysis Predicting to Relationship Separation

Hazard and survival curves

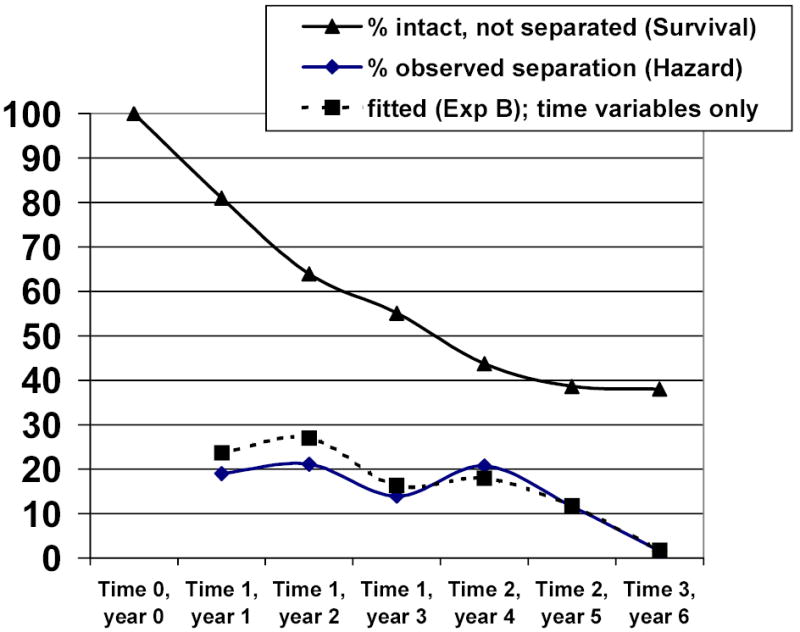

The observed and fitted hazard plots and survival curve are shown in Figure 1. The plots represent the risk for separation and show the percentage of couples who separated in each of the 6 years of the study, given they had not already separated in a prior year. The hazard of relationship separation was highest in the first 4 years of the period and then dropped sharply in Years 5 and 6. The survival rate decreased gradually; by the first year 19% and by the third year 45% of the couples separated. After 6 years of the study period, 62% of the couples had separated (see Table 1).

Figure 1.

Survival plot and hazard function for relationship separation.

Table 1.

Relationship Separation Across the 6-Year Study Period

| Year | Number | % | Cumulative % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | 19 | 19 |

| 2 | 27 | 17 | 36 |

| 3 | 14 | 9 | 45 |

| 4 | 18 | 11 | 56 |

| 5 | 8 | 5 | 61 |

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 62 |

Univariate analyses

To examine the individual effects of each predictor, univariate logistic regressions were first conducted (Table 2, Column 1). The variables representing time were entered first into the logistic regression, followed by one of the independent variables. Length of relationship at T1 was a fixed or time-invariant predictor, whereas the other predictors were time varying, as previously described. As expected, of the contextual factors, relationship length at T1 and relationship type were significantly predictive of relationship dissolution. Couples with longer relationships showed reduced odds of separation by 0.4% per week of relationship length. Compared to cohabiting couples, couples that were married had reduced odds of separation by 2.3%, and cohabiting couples had a similar reduction in odds of separation in comparison to dating couples. Also, as expected, having higher relationship satisfaction significantly reduced the odds of separation by 46%. As predicted, having higher levels of physical aggression significantly increased the odds of separation by 162.5%.

Table 2.

Event History Models Predicting Relationship Separation from Contextual Factors, Aggression, and Satisfaction

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | B | Exp B | p | B | Exp | p |

| Contextual factors | ||||||

| Length of relationship (T1) | −.004 | .996 | .029 | −.003 | .997 | .085 |

| Relationship type | −.023 | .977 | .001 | −.025 | .975 | .009 |

| Child in household | −.254 | .776 | .310 | −.082 | .921 | .789 |

| Aggression | ||||||

| Physical aggression | .965 | 2.625 | .027 | 1.543 | 4.676 | .009 |

| Psychological aggression | .124 | 1.132 | .503 | −.410 | .663 | .170 |

| Satisfaction | ||||||

| Relationship satisfaction | −.617 | .539 | .001 | −.346 | .707 | .093 |

Note. The time variables that were included in the analyses were not included in the table.

Multivariate analyses

Multivariate logistic regressions were then conducted to test the effect of physical aggression in the presence of the contextual factors, psychological aggression, and satisfaction (Table 2, Column 2). Again, the variables representing time were entered first, followed by the contextual factors, aggression, and satisfaction variables. The time variables were significant, and the resulting block χ2 was significant, χ2(590, df = 6) 330.00, p < .001, with a Nagelkerke R2 of .57. When the contextual factors, aggression, and satisfaction variables were entered, the block χ2 was significant, χ2 (590, df = 6) 29.83, p < .001, with a Nagelkerke R2 of .61, and the model total χ2 was significant, χ2 (590, df = 12), 359.83, p < .001. Of the contextual factors, relationship type was a significant predictor for relationship outcome; couples that were married had reduced odds of separation by 2.5% compared to couples that were cohabiting, and cohabiting couples showed a similar reduction in odds of separation compared to dating couples. As originally hypothesized and consistent with the univariate findings, physical aggression was significantly predictive of a higher likelihood of relationship separation, even when the other predictors were included in the model. Physical aggression increased the odds of relationship instability by 368%. Contrary to the univariate findings, in the multivariate analyses, relationship satisfaction and length of relationship were not significantly predictive of a higher probability of the relationship remaining intact.

Discussion

This study examined whether dyadic physical aggression in the romantic relationships of young, at-risk couples had a detrimental influence on their relationship longevity over approximately a 6-year period. By end of Year 3, 45% of the couples separated, and by end of Year 6, 62% of couples dissolved their relationships. Lawrence and Bradbury (2001) reported that by end of first 4 years 70% of the aggressive newlywed couples had experienced failure of marriage assessed by either divorce/separation or low relationship satisfaction. Our findings with aggressive and nonaggressive at-risk couples from a community sample appear to be comparable to those of Lawrence and Bradbury’s.

Based on the dynamic developmental-systems model of the associations of contextual factors and couples’ aggression to relationship outcomes and the findings primarily with newlywed couples that physical aggression predicts divorce, we expected (a) physical aggression, rather than psychological aggression, would be a risk factor for relationship dissolution, (b) physical aggression would have additive predictive power for relationship dissolution in addition to relationship satisfaction, and (c) the effects of contextual factors on dissolution would primarily be accounted for by aggressive interactions. In univariate models, higher levels of physical aggression, relationship contextual factors including shorter relationship durations and relationship type (cohabiting vs. marital and dating vs. cohabiting), and lower relationship satisfaction were each predictive of relationship separation. However, in the multivariate prediction model, only physical aggression and relationship type were significant predictors of relationship dissolution. The effects of prior relationship satisfaction and length of relationship were reduced and no longer significant. Thus, physical aggression and type of relationship predicted relationship separation beyond the effects of an unhappy relationship, psychological aggression, length of relationship, and having children in the household. It is interesting to note that relationship satisfaction was only modestly related to physical aggression in the expected inverse direction at the later time point. This reflects the complicated nature of physical aggression in couples’ relationships; for some couples, physical aggression may not necessarily impact their views of their partner and relationship. To some extent, this is in line with Gottman, Coan, Carrere, and Swanson’s (1998) finding that positive affect (e.g., humor, interest, and affection) observed during problem-solving tasks was the only affective process that was predictive of both relationship stability and satisfaction for newlywed couples. None of the negative affective processes (e.g., reciprocation or escalation of negative affect) were related to relationship satisfaction. The link between physical aggression and relationship satisfaction clearly warrants further investigation.

The likelihood that physical aggression is associated with relationship separation has now been found with newlywed couples (Rogge & Bradbury, 1999) and the present study of couples. It is an important extension of prior work to examine relationship processes and stability in community samples of couples that are representative of differing relationship structures, rather than only marital couples, particularly given the relatively large proportion of adults who cohabit. Consistent with previous work, not being married in the current study was also associated with relationship separation (Cohan & Kleinbaum, 2002). Dissolution rates for premarital cohabiting relationships at 49% were more than double the rate of 20% for first marriages within a 5-year period (National Center for Health Statistics, 2002). Couples that are unmarried may be at an even greater risk for relationship instability if they are also aggressive.

The young couples had a high prevalence of both physical aggression (as observed or reported by either partner) and relationship dissolution, with 80% engaging in physical aggression and 62% separating 6 years later. These rates are comparatively higher than the 48% of newlywed couples that reported physical aggression and the 32% dissolution rate 4 years later (Rogge & Bradbury, 1999), and they likely reflect differences in sample characteristics and methodology for detecting aggression. Couples in the present study were younger, less educated, and more likely to be working class than the couples in the newlywed study. Although some couples were married, others were cohabiting, and many had children in their households. We also had the unique opportunity to observe aggression as it occurred between couples in the moment and found that the observed aggression measure used in this study was able to identify additional couples that were observed as aggressive but did not report aggression in their relationships.

For couples that engage in aggression and do not separate, aggression may continue in their relationships. An important question to address is why couples stay together despite the aggression. Within a developmental-systems framework, understanding relationship erosion involves consideration not only of relationship processes but also the characteristics of the couple. Antisocial behavior in childhood and adolescence predicts later aggression toward a partner in early adulthood (Capaldi & Clark, 1998). Further, assortative partnering by antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms has been associated with increased risk for aggression toward a partner (Kim & Capaldi, 2004). Aggression toward a partner occurs in the context of relationships, yet its association with antisocial behavior indicates that it may be representative of a broader cluster of risk factors such as substance use, psychopathology, and criminal behavior (Leonard & Senchak, 1996). Young adults who engage in such behaviors may be less likely to consider aggression as problematic and, thus, be less likely to separate. However, these associated risk behaviors are also expected to be damaging to intimate relationships.

The generalization of findings regarding the association of physical aggression and relationship dissolution across studies indicates an important reason, in addition to injury prevention, for efforts to prevent physical aggression in the relationships of young couples. The early years of a couple’s relationship are a critical time for establishing interaction patterns. Couples who engage in physical aggression early on in their relationships may set in place negative interaction patterns that are difficult to change and that erode their relationships over time. Couples may need help to become aware of the risk from physical aggression to their future relationship and well being to ensure that they do not minimize or underestimate its impact and also to establish positive processes.

Despite the lack of predictive power of psychological aggression in the prediction model for relationship dissolution, the importance of psychological aggression should not be ignored. Strong correlations of .58 and .49 between psychological and physical aggression indicate that both types of aggression often coexist when the relationship involves aggression. Therefore, it is critical that intervention programs have components to assess and reduce psychological aggression in the relationship (O’Leary, 1999). The high prevalence rates of aggression in this sample indicated that there are a sizeable number of young couples with aggression in their relationships and that many of these couples have children who may also be impacted by the aggression. In light of the far-reaching consequences of aggression, focusing on dyadic relationship processes and individual risk factors is advocated as likely to be most effective in decreasing partner aggression and fostering healthy romantic relationships.

Footnotes

The Couples Study was supported by Grant RO1 HD 46364 from the Cognitive, Social, and Affective Development, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the Division of Epidemiology, Services, and Prevention Branch, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. PHS, with additional support from Grant P30 MH 46690 from the Prevention and Behavioral Medicine Research Branch, Division of Epidemiology and Services Research, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and Office of Research on Minority Health ORMH), U.S. PHS. We thank Jane Wilson and the assessment team for data collection and Sally Schwader for editorial assistance.

References

- Belsky J, Spanier GB, Rovine M. Stability and change in marriage across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1983;45:567–577. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM. Partner Interaction Questionnaire. Oregon Social Learning; Eugene: 1991. Unpublished instrument. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM. Dyadic Social Skills. Oregon Social Learning Center; Eugene: 1994. Unpublished instrument. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Clark S. Prospective family predictors of aggression toward female partners for at-risk young men. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1175–1188. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Crosby L. Observed and reported psychological and physical aggression in young at-risk couples. Social Development. 1997;6:184–206. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Kim HK. Typological approaches in research on violence in couples: The solution or part of the problem? Oregon Social Learning Center; Eugene: 2005. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Owen LD. Physical aggression in a community sample of at-risk, young couples: Gender comparisons for high frequency, injury, and fear. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:425–440. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.3.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Shortt JW, Crosby L. Physical and psychological aggression in at-risk, young couples: Stability and change in young adulthood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2003;49:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A life span developmental systems perspective on aggression toward a partner. In: Pinsof WM, Lebow JL, editors. Family Psychology: The Art of the Science. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 141–167. [Google Scholar]

- Cohan CL, Kleinbaum S. Toward a greater understanding of the cohabitation effect: Premarital cohabitation and marital communication. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:180–192. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CP, Cowan PA. When partners become parents. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- DeMaris A. Till discord do us part: The role of physical and verbal conflict in union disruption. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:683–692. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Coan J, Carrere S, Swanson C. Predicting marital happiness and stability from newlywed interactions. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, O’Leary KD, Jouriles EN. Alcohol and aggressive personality styles: Potentiators of serious physical aggression against wives? Journal of Family Psychology. 1995;9:44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Huston TL, Caughlin JP, Houts RM, Smith SE, George LJ. The connubial crucible: Newlywed years as predictors of marital delight, distress, and divorce. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:237–252. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, method, and research. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. The national comorbidity survey. DIS Newsletter. 1990;7(12):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Capaldi DM. The association of antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms between partners and risk for aggression in romantic relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:82–96. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. Predicting the timing of separation and marital satisfaction: An eight-year prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:163–179. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Bradbury TN. Physical aggression and marital dysfunction: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, . 2001;15:135–154. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Senchak M. Prospective prediction of husband marital aggression within newlywed couples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:369–380. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall LL. Effects of men’s subtle and overt psychological abuse on low–income women. Violence and Victims. 1999;14:69–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, O’Leary KD. Psychological aggression predicts physical aggression in early marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:579–582. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Vital and Health Statistics Series, 23, Number 22. Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.; 2002. Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and remarriage in the U.S. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD. Psychological abuse: A variable deserving critical attention in domestic violence. Violence and Victims. 1999;14:3–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Barling J, Arias I, Rosenbaum A, Malone J, Tyree A. Prevalence and stability of marital aggression between spouses: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:263–268. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pears K, Pierce S, Kim HK, Capaldi DM, Owen LD. The timing of entry into fatherhood in young, at-risk men: Familial, individual, and sexual risk predictors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;64:429–447. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogge RD, Bradbury TN. Til violence does us part: The differing roles of communication and aggression in predicting adverse marital outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:340–351. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Leonard KE. Husbands’ and wives’ marital adjustment, verbal aggression, and physical aggression as longitudinal predictors of physical aggression in early marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:28–37. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Stets JE. Cohabiting and marital aggression: The role of social isolation. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:669–680. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scale. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs J, Crosby L, Forgatch M, Capaldi DM. Family and Peer Process Code: Training manual: A synthesis of three OSLC behavior codes. Oregon Social Learning Center; Eugene: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Leonard KE. The impact of marital aggression on women’s psychological and marital functioning in a newlywed sample. Journal of Family Violence. 2001;16:115–130. [Google Scholar]

- White L, Rogers SJ. The economic context of relationship outcomes: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:1035–1051. [Google Scholar]