Abstract

College students overestimate other students’ drinking behavior (descriptive norms) and attitudes (injunctive norms). This study explored the effects of demographics, norm type, and reference group on the magnitude of self-other differences (SODs). Participants (N = 1611; 64% women) completed surveys assessing demographics, drinking patterns, and perceived norms. A subset of 122 students provided consumption data one month later to test predictors of changes in drinking. Overall, women and non-Greeks reported larger SODs for both norm types compared to men and Greeks. Heavier drinkers reported smaller SODs. Gender-by-reference group interactions revealed that women had larger SODs for reference groups increasingly distal to them; for men, the largest SODs occur for close friends versus more distal groups. Larger SODs for descriptive norms predicted increases in drinking, consistent with Social Norms Theory.

Patterns and Importance of Self-Other Differences in College Drinking Norms

Over the past decade, excessive alcohol use has become recognized as the most important health hazard for college students (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2001). Approximately 40% of college students (nearly 50% of males) drink heavily at least once every 2 weeks (O’Malley & Johnston, 2002; Wechsler et al., 2002). Heavy (or binge) drinking has been defined as having 5 or more drinks in a single occasion (4 or more drinks for women; Wechsler et al., 1998). Heavy alcohol use tends to be associated with in negative consequences that include damage to self, others, and property (see Perkins, 2002 for a review).

The frequency and consequences of drinking among college students has prompted research on hypothesized moderators of excessive drinking, including perceived drinking norms (Borsari & Carey, 2001, 2003; Perkins 1997, 2002, 2003). Both descriptive and injunctive norms are assessed frequently in the college drinking environment. Descriptive norms refer to the perception of other’s quantity and frequency of drinking, and are based largely on behavioral observations of how people consume alcohol in discrete drinking situations. Injunctive norms, on the other hand, refer to the perceived approval of or attitudes about drinking, and represent perceived moral rules of the peer group. Injunctive norms assist an individual in determining acceptable and unacceptable social behaviors (Cialdini, Kallgren, & Reno, 1991). Students tend to overestimate both descriptive and injunctive norms; students often believe that peers drink more than they do (e.g., Perkins, 1997) and are more approving of alcohol use than they really are (e.g., Prentice & Miller, 1993). This finding has been observed internationally, both in Ireland (Agostinelli, Grube, & Morgan, 2003) and New Zealand (Kypri & Langley, 2003).

Attribution theory can help to explain the origins of norm overestimation (Perkins, 1997; 2003). Because students have limited knowledge about the actual behaviors and attitudes of other students, three social-cognitive processes may contribute to the perception that heavy drinking is common and approved of by others. First, when a student observes others drinking heavily, s/he assumes that such excessive use is representative of their personal dispositions (the so-called “fundamental attribution error”). This error is enhanced to the extent that a student is not a member of the target group (Miller & Prentice, 1994; Perkins, 1997). Second, exemplars of heavy drinking tend to be salient in the collegiate social environment. Drunken individuals are more memorable than students who were drinking moderately. In addition, students tend to discuss incidents of drunkenness, rather than sober or responsible behaviors. Thus, exemplars of excessive drinking are more easily recalled than exemplars of moderation (the “availability heuristic;” Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). Third, the media often depict college students as heavy drinkers in films (e.g., Animal House, Old School) and headlines describe the latest alcohol-related injury or fatality. Thus, the cultural stereotype of college students reinforces the perception that they are heavy drinkers. It is likely that these factors facilitate the overestimation of other students’ alcohol use and approval of drinking.

Exaggerated perceptions of normative behavior are linked to personal drinking behavior, such that heavier drinkers endorse more permissive attitudes about drinking behavior and higher drinking norms (e.g., Perkins & Berkowitz, 1986; Perkins & Wechsler, 1996). These perceptions may remain unchallenged, because heavy drinkers tend to associate with other heavy drinkers (Aas & Klepp, 1992; Perkins & Wechsler, 1996). Such perceptions can create a permissive environment for students to act in ways consistent with the perceived group norm. Students may feel pressures to match the drinking they perceive other students doing (descriptive norm) and approving of (injunctive norm). Both cross sectional (Baer, Stacy & Larimer, 1991; Wood, Read, Palfai & Stevenson, 2001) and longitudinal (Kahler, Read, Wood & Palfai, 2003; Larimer, Turner, Mallet, & Geisner, 2004; Read, Wood, Kahler, Maddock & Palfai, 2003) surveys reveal positive relationships between perceived norms and both alcohol use and problems.

Because of exaggerated perceptions of norms, students tend to rate their own behaviors and attitudes as less extreme than those of their peers. (e.g., Baer & Carney, 1993; Baer, Stacy & Larimer, 1991; Bourgeois & Bowen, 2001; Perkins & Berkowitz, 1986). A recent meta-analysis of 23 studies (Borsari & Carey, 2003) revealed that the average student perceives that others drink more heavily and hold more favorable attitudes towards drinking than s/he does. This misperception can be referred to as a positive self-other difference, or a positive SOD.

Although perceived drinking norms correlate strongly with drinking behaviors, this correlation is not perfect; both estimates of the norm (other) and personal behavior/attitudes (self) introduce variability in the size of SODs. Thus, factors that increase or decrease the norm estimate, or raise or lower the individual’s drinking behavior and/or attitudes, should affect the size of SODs. Borsari and Carey (2003) identified several factors that predicted the size of SODs in perceived norms. Larger SODs were observed for injunctive norms compared to descriptive norms, for women compared to men, for non-Greeks compared to Greeks, and for more distal reference groups (all college students) compared to more proximal groups (close friends).

Social norms theorists hold that higher perceived norms predict higher levels of drinking, and positive SODs may “draw up” the alcohol use of light-moderate drinkers and/or buffer heavier drinking students from realization of their extreme drinking (Perkins, 2002). Based on this assumption, prevention efforts often attempt to correct exaggerated norms perception, and SODs may be incorporated into feedback-based interventions. Group (Fromme & Corbin, 2004), individual (Borsari & Carey, 2000; 2005) and mailed (Collins et al. 2002) prevention interventions have included feedback on student estimates of norms, real norms data, and the students’ self-reported drinking patterns. The goals of providing this feedback include (a) replacing exaggerated perceived norms with the accurate norm, and in doing so (b) creating new, more accurate, SODs. This process may reduce the pressure on lighter drinking students to conform to elevated descriptive and injunctive norms (Perkins 1997, 2003). Also, feedback that the true SOD is negative (i.e., the recipient of the feedback is actually drinking more than peers) may prompt some heavier drinkers to reevaluate their drinking patterns. The effectiveness of social norms interventions has been demonstrated using feedback for both injunctive (Schroeder & Prentice, 1998) and descriptive (Haines & Barker, 2003; Perkins & Craig, 2003) norms. Indeed, recent controlled studies have demonstrated that short-term drinking reductions are mediated by reductions in perceived drinking norms (Borsari & Carey, 2000; Neighbors, Larimer, & Lewis, 2004). Because SODs play an implicit role in normative feedback interventions, it is important to understand the sources of variation in SODs.

The purpose of the present study is to further specify factors that contribute to the magnitude of SODs, and to evaluate the influence of SODs on subsequent drinking behavior. Our previous meta-analysis could not address several issues about variation in SODs among college drinkers. For example, studies included in the meta-analyses often reported either injunctive or descriptive norms, but not both, precluding direct comparisons in the same sample using the same reference group (the “other” in the SOD). In addition, an independent assessment of the association of Greek status and SOD norm type was not possible, because all Greek-only studies evaluated descriptive norms and all non-Greek only studies evaluated injunctive norms. Thus, the first three hypotheses are:

SODs will be greater for injunctive norms compared to descriptive norms. The current study will provide a direct test of the magnitude of injunctive and descriptive norms using the same reference group (i.e., other students at this university).

Women, and non-Greeks will produce larger SODs for injunctive norms relative to men and Greeks. Testing this hypothesis extends our previous findings by evaluating the effect of Greek status on injunctive norms.

Women, and non-Greeks will produce larger SODs for descriptive norms relative to men and Greeks. In addition, descriptive SODs will be greater for more distal reference groups (students in US vs. students on campus vs. close friends). The test of this hypothesis extends or knowledge by exploring the effects of gender and Greek status on SODs of various reference groups.

Our next hypothesis addressed the associations between drinking behaviors and the magnitude of SODs. The Borsari and Carey (2003) meta-analysis could not evaluate the relationship of SODs and alcohol use because of a reliance on group means. If larger SODs are found for women and non-Greeks, as suggested by previous research, one can hypothesize that lower drinking patterns may be associated with larger SODs. Perkins and Berkowitz (1986) reported a negative relationship between drinking level and SODs for injunctive norms. However, a direct test of the relationship of drinking level and magnitude of SODs for descriptive norms has not been done. Thus, we hypothesize that:

4. Drinking quantity will be negatively related to SODs for both injunctive and descriptive norms. That is, as drinking levels increase, SODs will decrease.

Lastly, this study will test the hypothesis, consistent with social norms theory (Perkins, 2003) that large SODs lead to increases in drinking. Evidence from norms-based interventions supports the causal link between reducing perceived norms and drinking reduction. However, there is no direct evidence to support the assumption that large SODs set the stage for increased drinking. We hypothesize that the perception that the norm is greater than one’s own drinking behavior (i.e., a large SOD) will have a disinhibiting effect on subsequent drinking that is independent of the effect of the norm on drinking. Thus, we predict that:

5. Larger SODs will result in an increase in drinking in prospective analyses.

Method

Participants

Participants were 1611 undergraduates (64% women) attending a large private university in the northeastern United States, who were enrolled in an introductory psychology course. The sample was recruited over 5 semesters as follows: Fall 2001, n = 288; Spring 2002, n = 252; Fall 2002, n = 217; Spring 2003, n = 397; Fall 2003, n = 457. All received course credit for their participation. The sample was mostly freshmen (53%) or sophomores (33%); most were white (81%), living in on-campus housing (81%); only 17% were members of fraternities or sororities, consistent with the University policy of delaying rush to the second semester of freshman year.

A subset of 122 participants repeated the survey one month after the original survey date. These participants were eligible for a prevention intervention study because they reported a heavy drinking episode at least 4 times in the last month, and were subsequently randomized into an assessment-only condition (Carey, Carey, Maisto, & Henson, 2005). This subset was similar demographically to the larger sample: 64% were women; 60% were freshmen and 29% were sophomores; 84% were white; 81% lived on campus; and 20% were members of fraternities or sororities (Greeks).

Measures

Measures were assembled into a scannable packet, and addressed demographics, drinking patterns, descriptive and injunctive drinking norms, and personality constructs.

Demographics. Participants provided information regarding gender, age, race/ethnicity, residence, and Greek affiliation. They also reported their weight to allow calculation of blood alcohol concentrations.

Drinking patterns. All drinking assessments used the last month as a uniform time frame. A modified version of the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Dimeff et al., 1999) was used to record days in a typical week (over the last month) on which alcohol was consumed, and the number of standard drinks consumed on each drinking day. For this and all subsequent assessments, a drink was defined as a 10-12 oz. can or bottle of 4-5% beer; 4 oz. glass of 12% table wine; 12 oz. bottle or can of wine cooler; 1.25 oz. shot of 80 proof liquor either straight or in a mixed drink. A similar grid assessed the number of drinks per day consumed in the heaviest drinking week of the last month. The DDQ allows calculation of drinks per typical week, mean drinks per drinking day, and drinks consumed in the heaviest week of the last month. One-month stability coefficients for these derived variables in the subset of 122 participants providing longitudinal data are .52, .45, and .59, respectively. In addition, participants estimated the daily number of standard drinks consumed, and the typical hours spent drinking (allowing calculation of typical BAC) and the maximum number of drinks consumed in a single day in the last month, and the number of hours from first to last drink on that day (allowing calculation of peak BAC).

Drinking norms. Descriptive norms were assessed using a modification of the procedure described by Baer, Stacy, and Larimer (1991). The DDQ grid was used to assess average daily estimates for the following reference groups: (a) participant’s close friends of the same gender, (b) the typical student of the same gender at their university, and (c) the typical college student of the same gender in the U.S. Thus, estimated frequency and quantity of peers’ drinking can be calculated across three reference groups that varied in proximity to the participant. Gender-specific descriptive norm estimates were obtained because of data that suggest that they are more strongly associated with heavy drinking than gender-nonspecific norms (Lewis & Neighbors, 2004). One-month stability coefficients (N= 122) for these norm estimates were .75, .63, and .65, respectively.

Injunctive norms were assessed using five statements described by Perkins and Berkowitz (1986). Students first selected the statement that they agreed with most and then selected the one that best represented the attitude of other students at their university. The statements ranged from “drinking is never a good thing” to “frequently getting drunk is okay if that’s what the individual wants to do.” The one-month stability coefficient for injunctive norm estimates was significant (kappa = .35, p < .0001; N= 122); 88% of the retest estimates of others’ approval of drinking were within 1 point of the original.

Social Desirability. The 13-item version of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (Reynolds, 1982) was administered to assess social desirability bias. The short social desirability scale correlates highly with the original version r = .93, and is internally consistent (alpha = .76 in original study; .67 in this study).

Procedure

Students enrolled in Introductory Psychology were recruited to a “College Health Study.” All provided written informed consent prior to completing the surveys. The measures were administered in groups that met in classrooms on campus. Research staff provided instructions for completing the booklet, and provided additional orientation to the weekly grids to ensure that participants understood the task. All forms were labeled with a unique code number, and consent information was separated from the booklets when the students turned them in.

Students who reported four or more heavy drinking episodes in the last month were invited to participate in an alcohol abuse prevention study. Of these, 122 students were randomly assigned to the assessment-only control condition and provided the longitudinal data for the present study. One month after the initial survey assessment, these students completed a second survey packet, which included all drinking outcome measures. Nearly all (97%) of the students randomized into the prevention study provided one-month follow-up data for course credit.

Data Analysis Strategy

Self-other differences for injunctive norms were created by subtracting attitudes towards drinking behaviors endorsed by the participant from the perceived attitude held by others. A positive SOD reflects more permissive attitudes held by others whereas a negative score reflects more permissive attitudes held by the participants. Similarly, SODs for descriptive norms were created by subtracting the participants’ drinks per week from the estimated drinks per week for close friends, other students at this university, and all college students in the U.S. (all gender-matched to participant). Thus, a positive SOD represents perceptions that the reference group drank more per week than did the participant. Because injunctive and descriptive norms used different metrics (0-4 scale vs. drinks/week), SODs were standardized for direct comparisons.

Paired sample t-tests were used to compare the magnitude of SODs across norm type. Comparisons of injunctive SODs across gender and Greek status were achieved with independent sample t-tests. Pearson correlations were calculated to evaluate strength and directionality of relationships among drinking, norms and SODs. Comparisons of descriptive SODs across reference groups, gender, and Greek status were achieved using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM; Singer & Willett, 2003). In these models, both main effects of gender, Greek status, and reference group, and interactions of the two between-subjects factors with reference group were also investigated. We performed this analysis in three steps. First, each predictor variable and all possible interactions were entered into the model. In these analyses, we used dummy-codes for gender and Greek status, and included a term representing the linear effect of repeated estimates of the drinking of the other reference groups. Second, non-significant interactions and predictors were dropped. Third, we added baseline drinks per week (centered around the group mean) to the final model. For the final model, two different types of covariance structures (compound symmetry and unstructured covariance) were compared, following procedures described in Snijders and Bosker (1999). Maximum likelihood ratio tests revealed that the unstructured covariance matrix provided the better fitting model. Denominator degrees of freedom were determined using the Satterthwaite approximation method.

Finally, the effect of SODs on changes in drinking (n = 122) was evaluated with multiple regression. The criterion variable consisted of a difference score created by subtracting baseline drinks per week from follow-up drinks per week. Thus positive scores represented increases in average drinking during the intervening month whereas negative scores represented decreases. The model was created in three steps. In the first step, gender, Greek status, and baseline social desirability were entered to predict changes in alcohol use. The second step added baseline injunctive and descriptive norms. In the third step, descriptive and injunctive SODS were added.

Results

Sample Description

Most (89%) of the sample reported at the first assessment that they had consumed alcohol at least once in the last month. The mean number of drinks per week for the sample was 12.5 (SD = 12.8), typical BAC was .088% (SD = .11), and peak BAC was .164% (SD = .11). As shown in the last columns of Table 1, estimates of number of drinks per week for close friends of the same gender, others of the same gender on campus, and U.S. college students of the same gender ranged from 18.6 to 21.4, all exceeding the self-reported consumption of this sample.

Table 1.

Means, SDs, and Correlations Among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Injunctive – self | 1.00 | .18** | -.61** | .44** | .33** | .14** | .12** | -.06** | -.31** | -.29** | .34** | 1.92 | 0.82 |

| 2. Injunctive – campus | 1.00 | .67** | -.05* | .03 | .07* | .10* | .10** | .12** | .13** | .03 | 2.71 | 0.87 | |

| 3. SOD – injunctive | 1.00 | -.37** | -.22** | -.05* | -.02 | .13.** | .33** | .33** | -.27** | .78 | 1.1 | ||

| 4. Drinks/week for self | 1.00 | .70** | .55** | .41** | -.18** | -.54** | -.52** | .51** | 12.5 | 12.8 | |||

| 5. Drinks/week for friend | 1.00 | .57** | .49** | .57** | -.15** | -.19** | .35** | 18.6 | 14.8 | ||||

| 6. Drinks/week for campus | 1.00 | .82** | .24** | .48** | .33** | .20** | 20.5 | 12.4 | |||||

| 7. Drinks/week for U.S. | 1.00 | .21** | .37** | .57** | .19** | 21.4 | 13.2 | ||||||

| 8. SOD – friend | 1.00 | .41** | .35** | -.11** | 6.36 | 10.7 | |||||||

| 9. SOD – campus | 1.00 | .85** | -.31** | 7.88 | 12.8 | ||||||||

| 10. SOD – U.S. | 1.00 | -.29** | 8.87 | 14.0 | |||||||||

| 11. RAPI | 1.00 | 5.04 | 5.8 |

Note: N = 1601; SOD = self-other difference; U.S. = United States; RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Hypothesis 1: SODs for injunctive versus descriptive norms

The standardized SODs of perceived injunctive norms and descriptive norms of typical students at the university were compared. A t-test revealed no difference in the magnitude of SODs in descriptive and injunctive norms (t = .02, 1598 df, p = .99).

Hypothesis 2: Injunctive Self-Other Differences by Gender and Greek Status

A t-test comparing injunctive SODs for men and women indicated that the women had significantly larger injunctive SODs than did men (Ms = .91 vs. .57; t = -6.05, 1587 df, p < .001). A t-test comparing injunctive SODs for non-Greeks and Greeks revealed that non-Greeks had larger SODs than did Greek members (Ms = .83 vs. .56; t = 3.88, 1598 df, p < .001).

Hypothesis 3: Descriptive Self-Other Differences by Gender, Greek Status, and Reference Group

Students in this sample perceived others as drinking more than themselves; such perceptions produced consistently positive SODs across four different reference groups (see Table 2). HLM analyses reveal that Greek status, gender, and reference group all were significantly associated with the size of perceived SODS. First, members of the Greek system had lower SODs than non-members (F = 7.36, 1/1578 df, p = 0.0068), shown in rows 4 and 5 of Table 2. Second, women perceived higher SODs than men (F = 29.83, 1/1578 df, p < .0001), shown in rows 2 and 3 of Table 2. However, a significant interaction was found between gender and reference group (F = 14.06, 2/1574 df, p < .0001). This indicates that women tended to see their female friends as drinking somewhat more than they do (smaller SODs), but perceived the typical female student on campus and the typical female student in the U.S. as drinking much more than they do (larger SODs). In contrast, men perceived the largest SODs with their male friends and relatively smaller SODs with the typical students on campus and in the US.

Table 2.

Gender and Greek Comparisons on Self-Reported Drinks per Week and Self-Other Differences Across Reference Groups.

| Self-Other Differences Across Reference Groups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Self-Reported Drinks/Week | Close Friend | Member of Fraternity/Sorority | SU Student | U.S. Student | |

| Total | 1599 | 12.5 (12.8) | 6.4 (10.8) | n/a | 7.9 (12.8) | 8.9 (14.0) a |

| Male | 574 | 17.3 (14.9) | 8.2 (13.8) | n/a | 6.8 (15.0) | 6.6 (15.5) b |

| Female | 1026 | 9.8 (10.3) | 5.2 (8.5) | n/a | 8.5 (11.4) | 10.1 (13.0) a |

| Non-Greek | 1330 | 11.2 (11.8) | 6.1 (10.5) | n/a | 8.7 (12.6) | 9.4 (13.8) b |

| Greek | 264 | 19.0 (14.6) | 7.9 (11.7) | 12.2 (17.6) | 3.7 (13.1) | 5.7 (14.8) c |

Note: All targets “of same gender”; positive self-other differences represent increases from self-reported drinks per week. Only members of the Greek system made estimates for drinks per week “of a typical member of your fraternity/sorority.”

= self < close friend < student on campus < student U.S., at p < .001

= self < close friend < student on campus = student in U.S. , at p < .05

= self < close friend < member of fraternity/sorority > student on campus = student in U.S., at p < .001

Hypothesis 4: Negative Relationships between SODs and Drinking Patterns

Pearson correlations among all variables are provided in Table 1. As seen there, self-reported drinks per week (row 4) are positively correlated with perceived descriptive norms (columns 5-7). The strongest relationship is between drinks per week for self and close friends of the same gender (r = .70), and the magnitude of the associations decreases the more distal the target (.55 for students at the university, .41 for all US college students). In contrast, drinks per week are negatively correlated with SODs, indicating that lower levels of drinking are associated with larger discrepancies between personal alcohol use and the perceived drinking of others (rs = -.18 for friends, -.54 for students at the university, -.52 for all US college students). A similar negative relationship was seen between drinks per week and injunctive SODS (r = -.37).

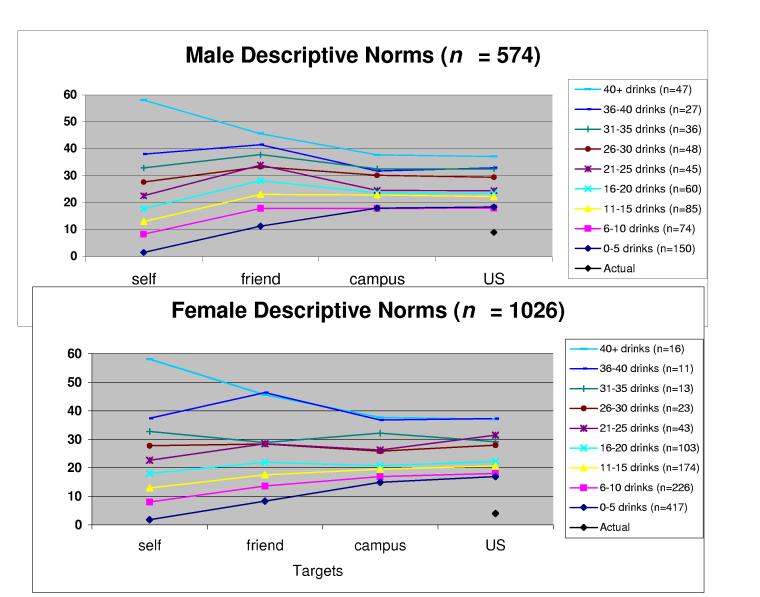

Because descriptive SODs are negatively associated with personal alcohol use, we explored whether level of alcohol use might moderate the effect of reference group on the magnitude of descriptive SODs. Therefore, we conducted exploratory HLM analyses to evaluate the effect of increasing levels of average consumption and reference group on SODs (see Figure 1). These analyses revealed that drinks per week is highly associated with SODs (F = 586.56, 1/1604 df, p < 0.0001); when personal alcohol use was entered as a covariate into the model described earlier for hypothesis 3, the main effect for reference group was no longer significant (p = .83). Specifically, SODs appeared to decrease as the level of personal alcohol use increased; for each drink per week the student consumed, SODs decreased by one-half drink. Furthermore, a significant reference group x alcohol use interaction (F = 113.98, 2/1608 df, p < 0.0001) indicates that as alcohol use increased, the significant differences among the SODs of different reference groups diminished. Figure 1 illustrate this interaction between drinking level and reference group for men (panel a) and women (panel b). The Figure also shows that positive SODs for campus and/or U.S. student comparisons can only be expected for light-moderate drinkers. At the higher drinking levels (e.g., > 30 drinks per week for men and > 25 for women), SODs approached zero or became negative. Thus, even though the heaviest drinkers reported the most exaggerated norms, they recognize that they drink more than other students, so their SODs do not fit the pattern seen for the majority of light-moderate drinkers.

Figure 1.

Mean drinks per week for self, friend, other students on campus, and U.S. students, by baseline drinking pattern. Panel 1 presents data for males and Panel 2 presents the same data for females.

Hypothesis 5: Large, Positive SODs Predict Changes in Drinking over Time.

Among the 122 participants who provided 30-day follow-up data, alcohol consumption decreased significantly, from a mean of 18 to 15.6 standard drinks per week (M change = -2.62, SD = 7.59, range -31 to 35 drinks; one-sample t = -3.8, 120 df, p < .001). A series of regression analyses were performed to predict 30-day changes in alcohol consumption from perceived norms and SODs (Table 3). In the first model, gender, Greek membership, and social desirability were entered as a block to predict changes in alcohol use; of these, only social desirability was a significant predictor. Specifically, those with higher social desirability scores at baseline tended to report greater reductions in alcohol use.

Table 3.

Prediction of Changes in Alcohol Use from Descriptive and Injunctive Norms and Corresponding Self-Other Differences.

| Variables | B | SEB | β | p | R2 | Adj. R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | .07* | .05* | ||||

| Gender | 2.56 | 2.04 | .11 | .212 | ||

| Greek Membership | 0.45 | 2.45 | .02 | .856 | ||

| Social Desirability | -0.92 | 0.33 | -.25 | .005 | ||

| Model 2 | 09* | .05* | ||||

| Gender | 1.88 | 2.19 | .08 | .392 | ||

| Greek Membership | -0.20 | 2.50 | -.01 | .936 | ||

| Social Desirability | -0.94 | 0.34 | -.26 | .006 | ||

| Descriptive Norm | -1.75 | 2.34 | -.07 | .456 | ||

| Injunctive Norm | 1.08 | 1.16 | .08 | .357 | ||

| Model 3 | .16** | .12** | ||||

| Gender | 2.15 | 1.98 | .09 | .280 | ||

| Greek Membership | 1.05 | 2.42 | .04 | .666 | ||

| Social Desirability | -1.04 | 0.32 | -.28 | .002 | ||

| Descriptive SOD | 0.32 | 0.09 | .30 | .001 | ||

| Injunctive SOD | -0.26 | 1.00 | -.02 | .798 |

Note. n = 120. SOD = self-other differences.

p < .05

p < .001

In the second model, we added a second block of predictor variables to the set of covariates, consisting of baseline descriptive norms (“how much do you think the typical student of your gender at this university drinks”) and injunctive norms (the attitudes of the typical student at their university). First-order correlations between the criterion (changes in drinks/week) and the norms variables were low (r = -.10 for descriptive norms and r = .10 for injunctive norms). For the 5 predictors in the second model, the tolerances (or percent of variance in each predictor unexplained by other predictors) ranged from .87 to .99, indicating that singularity is not a problem. Neither type of norms predicted changes in alcohol use (ΔR2 = .02). We had originally planned to enter the descriptive and injunctive SODs into the same model as the norms variables. However, there was evidence of suppression in the full model with regard to the descriptive norm and the descriptive SOD. Furthermore, the norms and SODs were significantly correlated (r = .52 for descriptive norms and r = .81 for injunctive norms with their respective SODs), indicating that the regression coefficients may be unstable due to multicollinearity. Hence we elected to build two parallel models predicting change in drinking: one with the covariates and the norms variables (model 2) and one with the covariates and the SOD variables (model 3). For each of these parallel models, we conducted diagnostics to rule out concerns regarding overlap between the two primary predictors and the criterion, and among all the predictors.

In the third model, both descriptive and injunctive SODs were added to the set of covariates. Correlations between the two predictors and the drinking change score were not high (r = .31 for descriptive SOD and r = .13 for injunctive SOD). For the 5 predictors in the third model, the tolerances ranged from .90 to .99, again confirming lack of singularity. In this model (ΔR2 = .09), both social desirability and descriptive SODs significantly predicted changes in alcohol use. Descriptive SODs demonstrated a significant positive relationship with changes in drinking: the larger the difference between the student’s personal use and the perceived use of the typical student, the more likely to be an increase between baseline and 30-day drinking.

Discussion

This study addressed patterns and correlates of SODs for descriptive and injunctive norms among college students. Consistent with prior research, our findings revealed positive SODs for both type of norms in the whole sample. This study extended knowledge by (a) simultaneously measuring descriptive and injunctive norms (b) in a large sample of undergraduates, and (c) systematically testing five hypotheses about variability within SODs.

With regard to the first hypothesis, we did not find evidence that injunctive SODs are greater than descriptive SODs. Although this finding was unexpected, methodological features of this study differed from those on which the original prediction was based. Uncontrolled sampling and measurement differences may have contributed to the meta-analytic finding that SODs for injunctive norms were larger than SODs for descriptive norms (Borsari & Carey, 2003). Often the studies included in the meta-analysis assessed only one type of norm; rarely did the same sample contribute data for both types of norms. In addition, assessment of injunctive norms varied considerably in the studies included in the meta-analysis. We acknowledge a potential limitation in our assessment approach. Specifically, the injunctive norms as measured in this study used “typical student at your university” as the reference group, whereas the descriptive norms used “typical student of your gender at your university.” We do not know if participants interpreted the typical student to be of their gender or not. However, the failure to find differences in SODs even with this slight mismatch in reference groups supports the conclusion that the relative magnitudes of SODs for injunctive and descriptive norms do not appear to vary when sample characteristics are held constant.

Our second and third hypotheses were supported; it appears that SODs vary within the sample in predictable ways. Women’s SODs for injunctive norms exceeded those of men, and injunctive SODs of non-Greeks exceed those of Greeks. Consistent with our previous findings (Borsari & Carey, 2003), women are more likely than men to perceive other students as being more approving of excessive drinking, relative to themselves. Furthermore, non-Greeks perceive others as being more approving of excessive drinking, relative to themselves, than do Greeks. Because members of Greek organizations generally perceive heavy drinking as more acceptable than nonmembers, they are more likely to have smaller SODs (Larimer et al., 1997). Our data are consistent with the interpretation that heavier drinkers (men and Greeks) have smaller SODs because the “self” component tends to be higher, whereas lighter drinkers (women and non-Greeks) have larger SODs because their “self” component tends to be lower. The risk for lighter drinkers stems from the process known as pluralistic ignorance (Prentice & Miller, 1993), or the incorrect belief that one’s attitudes or behaviors are different from others. The implication is that many students hold private misgivings about excessive drinking but assume that they are in the minority. Such a cognitive error can set the stage for students who are engaging in healthy behavior to conform to a false extreme norm. We propose that there is risk in perceiving an elevated norm, but also in perceiving that one’s current attitudes or behavior is far from that elevated norm - i.e., having a large SOD.

As hypothesized, descriptive SODs for distal reference groups were larger than those for more proximal reference groups, consistent with our previous meta-analysis (Borsari & Carey, 2003). Thus, as students compare themselves with other groups of the same gender, they tend to perceive more familiar groups (close friends) as more similar to them in drinking patterns than less familiar groups (U.S. students). More importantly, however, the current study extends knowledge by revealing a significant moderation by gender. That is, women reported the largest SODs for more distal groups, whereas men reported the largest SODs for their close male friends. Agostinelli, Grube and Morgan (2003) reported a similar interaction of reference group and gender for descriptive norms among high school students. These authors interpreted this finding as a social distancing effect, a motivated desire to see oneself as more conservative than increasingly distal others. Agostinelli et al. suggested that adolescent girls may be more prone to demonstrate social distancing by ascribing more extreme drinking behaviors to others. Even if social distancing is a self-protection strategy, it may nonetheless contribute to a perception of a permissive environment for drinking.

This gender by reference group interaction has implications for the use of normative feedback. That is, use of normative feedback with the intention of reducing SODs may be most effective for women and non-Greeks. Providing norms for distal comparison groups may not have as great an impact for men and Greek members because such norms result in smaller SODs. It may be informative to determine the accuracy of men’s perceptions of the elevated drinking of their close friends. It is possible that among men’s drinking companions, heavy drinking exemplars are quite salient, leading to greater use of the availability heuristic (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974) among men than among women. We hypothesize that use of more locally derived norms in personalized feedback would be more effective for heavier male drinkers.

Our fourth hypothesis was that how much a person drinks would be related to SODs. In general, the data from this and other studies (e.g., Kypri & Langley, 2003) show that the more one drinks the higher the perceived use of others. Estimates provided by heavier drinkers regarding all other reference groups were greater than those of lighter drinkers. However, the more one drinks, the smaller the SOD for both injunctive and descriptive norms. We were able to test this hypothesis directly by evaluating the relationship between self-reported drinking level and SODs. The results of this analysis confirmed the interpretation that men and Greeks have smaller SODs because these groups tend to be heavier drinkers. Although heavier drinkers may also be overestimating others’ drinking, their own drinking (the self component) is likely to be closer to the perceived norm (the other component), resulting in a smaller SOD. Thus the results of the previous analyses showing demographic correlates of SOD magnitude for descriptive norms should be reinterpreted in light of differences in drinking patterns rather than demographic characteristics per se.

Exploratory analyses revealed that the main effect of reference group on SODs is also moderated by personal drinking level. Positive SODs for distal reference groups were found only for lighter-moderate drinkers. In contrast, at the highest levels of drinking, the SODs became zero or negative; that is, among heavier drinkers, perceived norms could be lower than the self-reported drinking. An implication of this finding is that normative feedback will have a qualitatively different effect for very heavy drinkers versus light-moderate drinkers. On the one hand, providing correct normative information can result in a downward adjustment of norms (e.g. Borsari & Carey, 2000; Neighbors et al., 2004). For lighter drinkers, the mechanism of change in this case might be correction of perceived norms that are exaggerated, and the resultant reduction of social pressure to conform to the norm. This process may be described in part as correction of pluralistic ignorance (Prentice & Miller, 1993). On the other hand, providing correct normative information to very heavy drinkers will reveal that they are indeed drinking more than the real norm and perhaps confirm their assumptions that most other students drink less than they themselves do. It might be hypothesized in this case that a mechanism of change is the correction of false consensus (the inaccurate assumption that others are like you; Ross, Greene, & House, 1977) and a resulting discomfort with exceeding norms for drinking behavior. Greater awareness of this heterogeneity among college drinkers may help to inform how norms feedback and SODs are used in prevention interventions. Indeed, norms-based interventions may not be effective for all students. Some studies suggest that heavy drinking Greek members are less responsive to norms-based interventions (Barnett et al., 1996; Carter & Kahnweiler, 2000). At the very least, how norms feedback is provided must be adapted to the baseline level of drinking of the recipient.

Our final hypothesis addressed the relevance of SODs for future drinking behavior. We found that descriptive SODs predicted changes in drinking. These findings support the notion that students who perceive the drinking norm to be greater than their own drinking are vulnerable to increases in drinking (Perkins, 1997, 2003). Other researchers have also demonstrated prospective relationships between estimates of friends’ drinking and subsequent reports of high-risk drinking (Andrews, Tildesley, Hops, & Li, 2002). Due to the presence of suppression among variables that represented or contained norms, we could not directly assess the independent variance explained by SODs versus norms in the same model. However, we built alternate models that eliminated concerns about multicollinearity and ruled out excessive overlap between predictors and criterion variables. In these models, the additional variance accounted for by the SODs was statistically significant and greater than that of perceived norms; thus, our findings support the need for further attention to the construct of SOD in the study of college drinking.

Our findings must be considered in light of the limitations of this study. First, we relied on self-report data, which can be subject to bias and problems related to recall. Although we were able to control for the influence of social desirability bias, self-report provides only an approximation of drinking behavior. Second, our measure of injunctive norms may have limited the potential variation in the injunctive SOD variable. Because the current study used a 5-point scale, the SOD could only range from -4 to +4. In contrast, the SODs produced by comparisons of drinks per week had a much larger range of possible values. Third, our measure of injunctive norms did not allow comparisons across reference groups. This lack of parallelism prevents us from comparing norm type (injunctive versus descriptive SODs) with regard to the interactive effects of reference group, gender, and drinking levels. Given the relevance of reference group for descriptive SODs, future research should be designed to evaluate this influence on both injunctive and descriptive SODs in the same study. Finally, the sample is limited to primarily white students attending a private university in the northeastern U.S. Generalization to other populations of students must be done with caution.

In spite of these limitations, this study contributes to the drinking norms literature in several ways. Overall, positive SODs were observed, indicating that the average student believes that other students (a) drink more and (b) are more approving of drinking in excess. Importantly, our findings also show that this general pattern must be qualified. Larger injunctive and descriptive SODs were observed for traditionally lighter-drinking groups: women and students not involved in the Greek system. In the case of descriptive norms, the size of the SOD depends on the reference group selected to generate the “other” estimates. In addition, both gender and baseline drinking level interact with reference group in slightly different ways to determine the size of the SOD. Better understanding of the correlates of SOD has implications for our ability to predict future drinking behavior, as larger SODs predict larger increases in drinking. Thus, this study supports assertions of social norms theorists that students who perceive exaggerated drinking norms that exceed their own drinking are at risk for increasing their alcohol consumption.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01-AA12518 to Kate B. Carey. B. Borsari is now at Brown University, Providence, RI. S. A. Maisto is also affiliated with the Syracuse VA Center for Integrated Health Care. The authors thank Tanesha Cameron, James Henson, John Hustad, Carrie Luteran, Stephanie Martino, Dan Neal, Kalyani Subbiah, Dawn Sugarman, and Andrea Weber for their assistance with this project.

References

- Aas H, Klepp K-I. Adolescents’ alcohol use related to perceived norms. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 1992;33:315–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.1992.tb00920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agostinelli G, Grube JW, Morgan M. Social distancing in adolescents’ perceptions of alcohol use and social disapproval: The moderating roles of culture and gender. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2003;11:2354–2372. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Tildesley E, Hopps H, Li F. The influence of peers on young adult substance use. Health Psychology. 2002;21:349–357. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Carney MS. Biases in perceptions of the consequences of alcohol use among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:54–60. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Stacy A, Larimer M. Biases in perception of drinking norms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52:580–586. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett LA, Far JM, Mauss AL, Miller JA. Changing perceptions of peer norms as a drinking reduction program for college students. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 1996;41:39–62. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Effects of a brief motivational intervention with college student drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:428–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences in college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Two brief alcohol interventions for referred students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:296–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois MJ, Bowen A. Self-organization of alcohol-related attitudes and beliefs in a campus housing complex: An initial investigation. Health Psychology. 2001;20:434–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CA, Kahnweiler WM. The efficacy of the social norms approach to substance abuse prevention applied to fraternity men. Journal of American College Health. 2000;49:66–71. doi: 10.1080/07448480009596286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Kallgren CA, Reno RR. A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and re-evaluation of the role of norms in human behaviors. In: Zanna M, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 24. Academic Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Collins SE, Carey KB, Sliwinski M. Mailed personalized normative feedback as a brief intervention for at-risk college drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:559–567. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief alcohol screening and intervention for college students: A harm reduction approach. Guilford Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Corbin W. Prevention of heavy drinking and associated negative consequences among mandated and voluntary college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:1038–1049. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines MP, Barker GP. The Northern Illinois University experiment: A longitudinal case study of the social norms approach. In: Perkins HW, editor. The social norms approach to preventing school and college age substance abuse. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2003. pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Read JP, Wood MD, Palfai TP. Social environmental selection as a mediator of gender, ethnic, and personality effects on college student drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:226–234. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K, Langley JD. Perceived social norms and their relation to university student drinking. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2003;64:829–834. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Irvine D, Kilmer J, Marlatt GA. College drinking and the Greek system: Examining the role of perceived norms for high-risk behavior. Journal of College Student Development. 1997;38:587–598. [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Mallett KA, Geisner IM. Predicting drinking behavior and alcohol-related problems among fraternity and sorority members: Examining the role of descriptive and injunctive norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:203–212. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Gender-specific misperceptions of college student drinking norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:334–339. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DT, Prentice DA. Collective errors and errors about the collective. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1994;20:541–550. [Google Scholar]

- Miller DT, Prentice DA. The construction of social norms and standards. In: Higgins FT, Kruglanski AW, editors. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. Guilford; New York: 1996. pp. 799–829. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism What we know and what we need to learn [on-line] 2001. Available: http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/about/college [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lewis MA. Targeting misperceptions of desriptive drinking norms: Efficacy of a computer delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:434–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;Suppl. 14:23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. College student misperceptions of alcohol and other drug norms among peers: Explaining causes, consequences and implications for prevention programs. The Higher Education Center for Alcohol and Other Drug Prevention. U.S. Department of Education; 1997. pp. 177–206. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Surveying the damage: A review of research on consequences of alcohol misuse in college populations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;Suppl. 14:91–100. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. The social norms approach to preventing school and college age substance abuse. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW, Berkowitz AD. Perceiving the community norms of alcohol use among students: Some research implications for campus alcohol education programming. International Journal on Addictions. 1986;21:961–976. doi: 10.3109/10826088609077249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW, Craig DW. The Hobart and William Smith Colleges experiment: A synergistic social norms approach using print, electronic media and curriculum infusion to reduce collegiate problem drinking. In: Perkins HW, editor. The social norms approach to preventing school and college age substance abuse. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2003. pp. 35–64. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW, Wechsler H. Variation in perceived college drinking norms and its impact on alcohol abuse: A nationwide study. Journal of Drug Issues. 1996;26:961–974. [Google Scholar]

- Prentice DA, Miller DT. Pluralistic ignorance and alcohol use on campus: Some consequences of misperceiving the social norm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64:243–256. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Davidoff OJ, McLacken J, Campbell JF. Making the transition from high school to college: The role of alcohol-related social influence factors in students’ drinking. Substance Abuse. 2002;23:53–65. doi: 10.1080/08897070209511474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1982;38:119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ross L, Greene D, House P. The “false consensus effect”: An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1977;13:279–301. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder CM, Prentice DA. Exposing pluralistic ignorance to reduce alcohol use among college students. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1998;28:2150–2180. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis. Oxford University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel analysis. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science. 1974;185:1124–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4157.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Dowdall GW, Maenner G, Gledhill-Hoyt J, Lee H. Changes in binge drinking and related problems among American college students between 1993 and 1997. Journal of American College Health. 1998;47:57–68. doi: 10.1080/07448489809595621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Read JP, Palfai TP, Stevenson JF. Social influence processes and college student drinking: The mediational role of alcohol outcome expectancies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:32–43. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]