Abstract

Background

Auricular acupuncture is a promising method for postoperative pain relief. However, there is no evidence for its use after ambulatory surgery. Our aim was to test whether auricular acupuncture is better than invasive needle control for complementary analgesia after ambulatory knee surgery.

Methods

One hundred and twenty patients undergoing ambulatory arthroscopic knee surgery under standardized general anesthesia were randomly assigned to receive auricular acupuncture or a control procedure. Fixed indwelling acupuncture needles were inserted before surgery and retained in situ until the following morning. Postoperative rescue analgesia was directed to achieve pain intensity less than 40 mm on a 100-mm visual analogue scale. The primary outcome measure was the postoperative requirement for ibuprofen between surgery and examination the following morning.

Results

Intention-to-treat analysis showed that patients from the control group (n = 59) required more ibuprofen than patients from the auricular acupuncture group (n = 61): median (interquartile range) 600 (200–800) v. 200 (0–600) mg (p = 0.012). Pain intensity on a visual analogue scale was similar in both groups at all time points registered. The majority of patients in both groups believed that they had received true acupuncture and wanted to repeat it in future.

Interpretation

Auricular acupuncture reduced the requirement for ibuprofen after ambulatory knee surgery relative to an invasive needle control procedure.

Almost 70% of operative procedures in North America are currently performed in an ambulatory setting.1 Despite advances in surgical techniques and modern methods of analgesia, 45% of patients suffer pain at home after ambulatory surgery,2 and moderate to severe pain intensity at home is reported by 30% of ambulatory patients.3 Inadequate relief of pain after ambulatory surgery increases morbidity and health care costs and reduces patients' quality of life.4,5 To improve postoperative pain relief, an integrative approach combining pharmacologic methods and various complementary nonpharmacologic analgesic techniques has been recommended.6 Auricular acupuncture holds promise, as it is an easily performed technique that might be effective for treatment of both preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain in patients undergoing ambulatory surgery.7,8 However, there are reasonable doubts in the scientific community concerning the specificity of acupuncture,9 because the large randomized trials on auricular acupuncture for treatment of cocaine and alcohol dependence have found no difference between treatment and invasive needle control.10,11

Thus, after refining the methodology in a pilot study,12 we performed a randomized controlled trial to compare the postoperative analgesic effect of auricular acupuncture with invasive needle control in patients after ambulatory knee surgery.

Methods

This prospective, patient-and evaluator-blinded, controlled study was performed between August 2003 and September 2004 at the Ambulatory Orthopedic Surgery Center of the Ernst Moritz Arndt University, Greifswald, Germany. The study was approved by the university's ethics committee. Consecutive patients scheduled for arthroscopic ambulatory knee surgery under general anesthesia (without premedication) were enrolled in the study. Exclusion criteria were age younger than 18 years or older than 70 years; American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status III (severe systemic disease with functional limitation); history of opioid, sedative or hypnotic medication or excess alcohol use; inability to understand the consent form or how to use a visual analogue scale for pain measurement; local auricular infection or significant auricular deformation; or presence of prosthetic cardiac valves. Patients were withdrawn from the study if it was necessary to change the perioperative analgesia scheme, if the arthroscopic procedure was turned into open knee surgery or if the patient was unexpectedly admitted to hospital after the procedure.

On the day before surgery the patients were told that they would receive auricular acupuncture at specific points or nonacupuncture points in addition to standard postoperative analgesia, and they provided informed consent. On the day of surgery, before induction of anesthesia, the acupuncturist randomly assigned the patients into 2 groups, using the sealed-envelope method. After the acupuncture, the acupuncturist had no further personal contact with the study patients. The group allocation was unblinded after data analysis was completed.

Auricular acupuncture was performed by 1 of 3 certified acupuncturists, including T.I.U. and T.W. (each with more than 5 years of clinical practice). Disposable fixed indwelling steel auricular acupuncture needles (0.22 mm diameter and 1.5 mm long) were inserted before surgery, fixed with skin-coloured adhesive tape and retained in situ until the following morning. The auricular acupuncture group received acupuncture at 3 acupuncture points ipsilateral to the surgery site: knee joint, shenmen and lung. Three nonacupuncture points of the helix ipsilateral to the site of surgery were used for the invasive needle control. The choice of points for auricular acupuncture and sham control has been described in detail previously.12,13

The operations were conducted in the morning. Total intravenous anesthesia was performed according to a previously described standardized protocol,12 with monitoring of the depth of anesthesia (specifically, the bispectral index and core temperature). Incremental boluses of the weak opioid agonist piritramide (0.02 mg/kg) were administered in the anesthesia recovery room to keep the patients' reported pain intensity at less than 40 mm on a 100-mm visual analogue scale (VAS-100, where 0 = no pain and 100 = worst pain imaginable). The patients were discharged from the anesthesia recovery room according to standard discharge criteria after ambulatory surgery.14 Each patient received ibuprofen (single-dose, 200-mg tablets) and tramadol (50-mg tablets) for postoperative pain relief and written instructions on how to take the analgesics at home. The patients were encouraged to stimulate the needles every time they experienced more pain than on discharge from the anesthesia recovery room. If the pain persisted, the patients were instructed to take single doses of ibuprofen at intervals of at least 1 hour, to a maximum of 1400 mg, until the follow-up examination. If, after taking the maximal dose, the patient was still experiencing more pain than on discharge, tramadol at 1-hour intervals, to a maximum of 200 mg, was allowed. During the follow-up examination at 8 am the next day, the physician-in-charge withdrew the auricular acupuncture needles and registered the amount of ibuprofen and tramadol, reported by the patient as a tablet count. The patients, the medical staff managing the patients during surgery and the physicians involved in the data collection were blinded to group allocation and had no expertise in auricular acupuncture.

The primary outcome measure was the ibuprofen requirement during the period between surgery and the follow-up examination. A variety of secondary outcome measures were also assessed. Heart rate and blood pressure were recorded before and after acupuncture, 30 minutes after tracheal intubation, 30 minutes after the end of general anesthesia and before discharge.

All statistical analyses were intention-to-treat analyses. Normally distributed numeric data were analyzed with t tests and are reported as mean and standard deviation (SD). Variables measured at multiple time points were analyzed using the repeated-measures analysis of variance. Non-normally distributed or ordinal data were compared with the Mann–Whitney test and are reported as median and interquartile range (IQR). Dichotomous data were analyzed using the χ2 test and are reported as counts with percentages. Statistical significance was assessed at p < 0.05. The sample size was estimated to detect a 30% difference in postoperative ibuprofen requirement, using data from the pilot study.12 The sample size of 46 patients for each of the 2 groups was calculated to provide 90% power with α = 0.05. Anticipating a dropout rate of 15%, we adjusted the sample size to 60 patients per group. In an additional (sensitivity) analysis, missing values for the primary outcome measure were replaced by the median of the sample.

Results

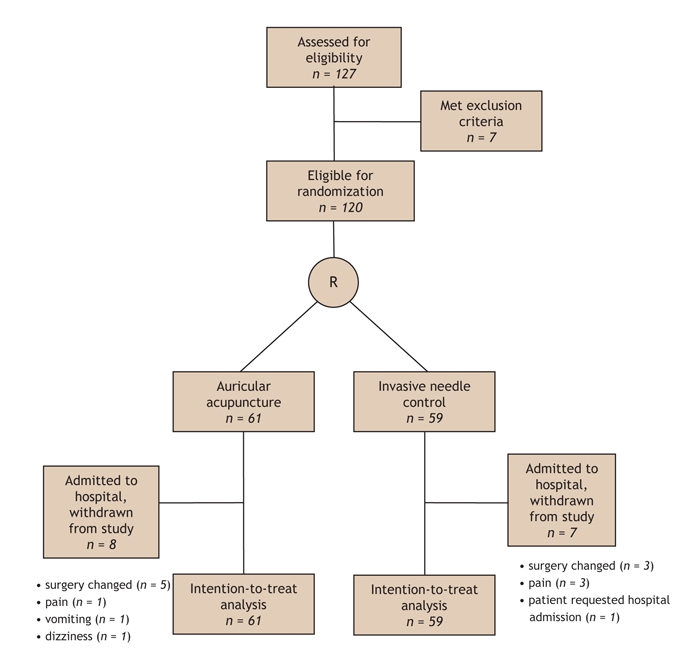

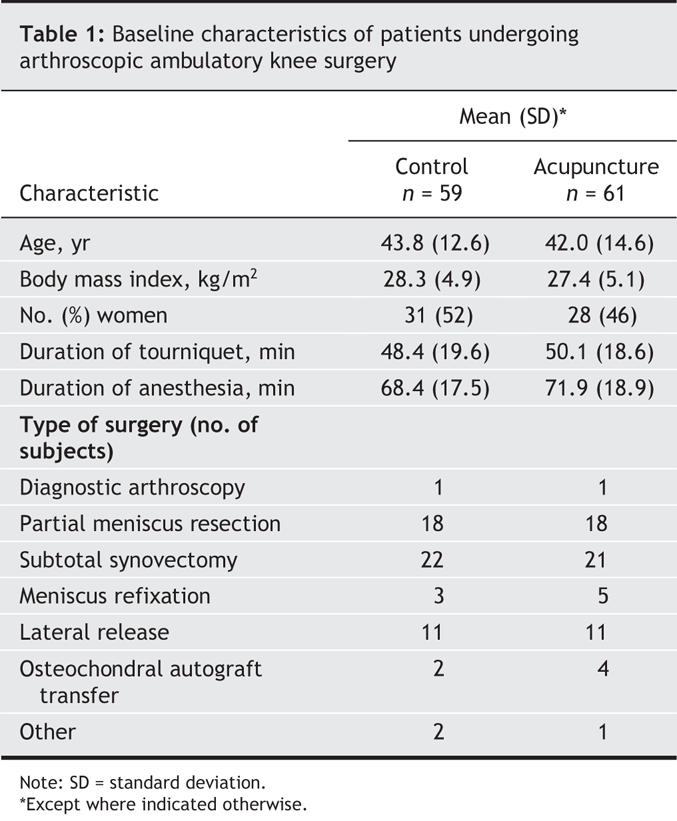

None of the patients in this study had previously received auricular acupuncture. Seven of the 127 patients who gave informed consent did not meet the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). There were no differences between the study groups in demographic characteristics, duration of tourniquet application and general anesthesia, type of surgery and withdrawal rate (Table 1). Unanticipated inpatient admission (7 patients in the control group and 8 in the treatment group) caused a withdrawal rate of 12% (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Flow diagram of the study. The primary unequal allocation of 61 v. 59 (rather than 60 v. 60) represents an error during preparation of the sealed envelopes before the study. For patients who were admitted to hospital and withdrawn from the study, the reasons for admission are provided. R = randomization.

Table 1

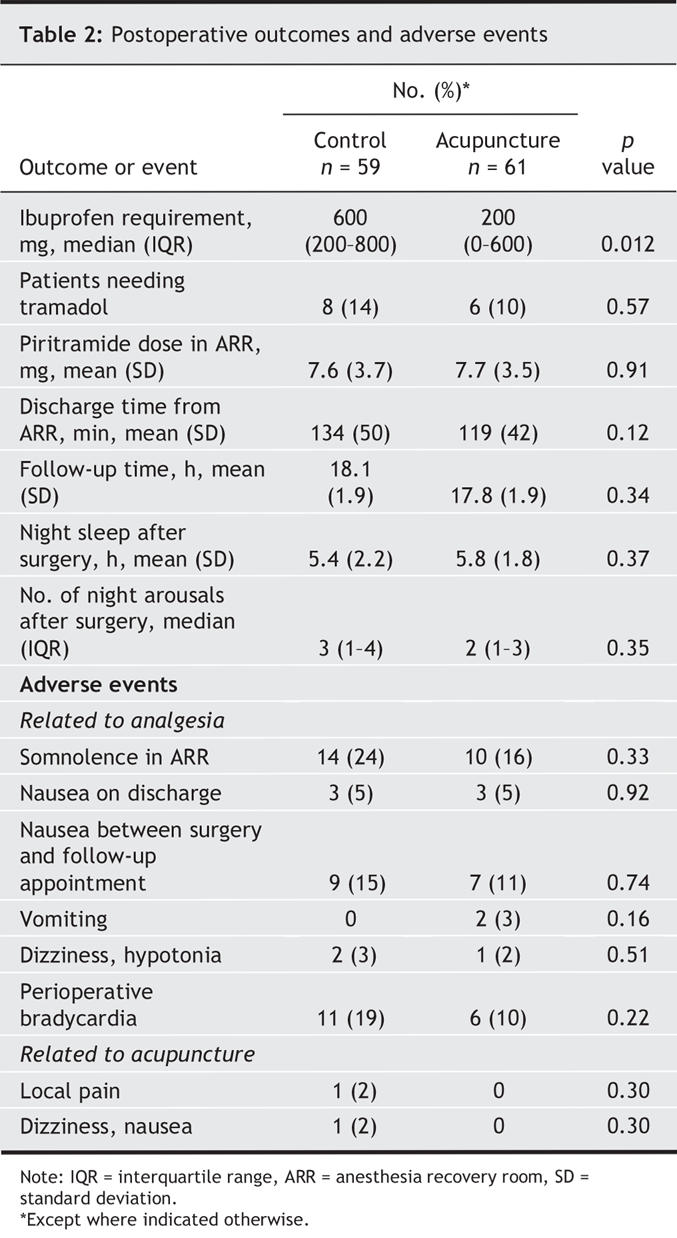

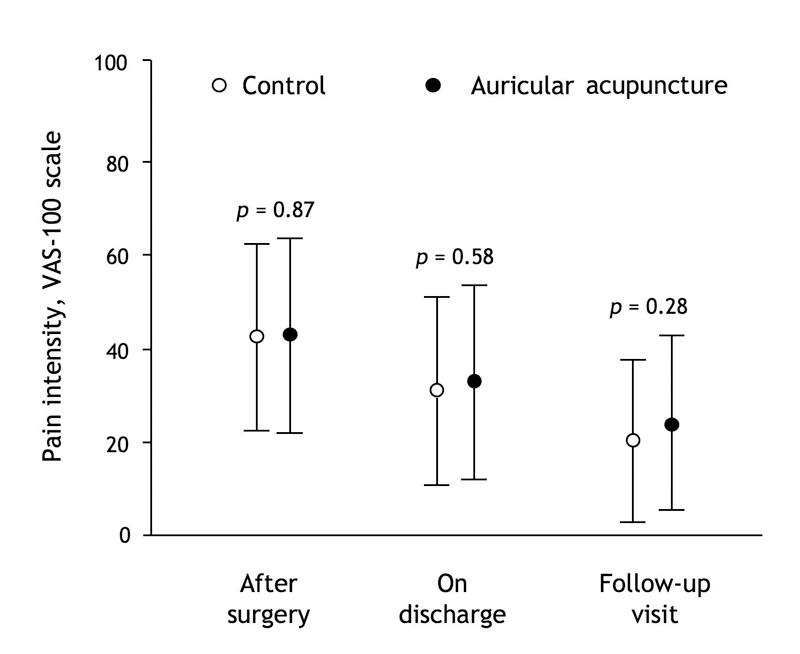

To achieve the target pain intensity of less than 40 mm on the VAS-100 during follow-up, the control patients required more ibuprofen than the patients who received acupuncture (median 600 mg v. 200 mg; p = 0.012) (Table 2). However, postoperative pain intensity scores were similar in the 2 groups at all time points registered (Fig. 2). More of the patients in the acupuncture group than in the control group required no postoperative analgesia with ibuprofen (20/52 [38%] v. 10/52 [19%], excluding patients with missing data; p = 0.025). Eight of the patients in the control group and 6 of those in the acupuncture group who reached the maximum daily ibuprofen dose also used tramadol (p = 0.57). There was a trend to discharge the patients in the acupuncture group earlier than the patients in the control group (mean difference in discharge time 15 minutes [95% confidence interval –4 to 33 minutes; p = 0.12) (Table 2). The amount of piritramide administered after surgery, the time from discharge until the follow-up appointment at 8 am the next day, the duration of night sleep and the number of arousals during the night after surgery were comparable (Table 2). Heart rate and blood pressure were similar in the 2 groups at all time points (data not shown). A sensitivity analysis in which the missing values for the primary outcome measure were replaced by the median of the sample yielded the comparable statistical results.

Table 2

Fig. 2: Mean pain intensity scores (and standard deviation) after ambulatory arthroscopic knee surgery on a 100-mm visual analogue scale.

Differences in patients' opinion concerning the success of blinding between the groups were not significant. Most patients in both groups believed that they had received true acupuncture and wanted to receive this type of therapy in the future (data not shown).

The incidence of analgesia-related side effects was similar in the 2 groups (Table 2). The incidence of perioperative bradycardia requiring atropine was higher in the control group, although this difference was not statistically significant (11 v. 6 patients; p = 0.22). One patient in the control group associated postoperative dizziness and nausea with acupuncture. Ten minutes after withdrawal of the needles the symptoms disappeared and the patient was discharged. Another patient in the control group reported that the needles produced localized pain at the sites of insertion and disturbed sleep. Both patients believed that they had received true acupuncture and, despite the reported problems, wanted to repeat it for perioperative complementary analgesia in the future.

Interpretation

We found that auricular acupuncture reduced the requirement for ibuprofen relative to invasive needle control after ambulatory arthroscopic knee surgery. The patients in both groups reported adequate pain relief, so the difference in ibuprofen requirement confirms the analgesic effect of auricular acupuncture, suggested earlier.15 Since invasive needle control produces weak analgesia,16 the genuine clinical effect of auricular acupuncture might have been greater than reported here. The overall incidence of nausea (16/120 [13%]) was consistent with that reported in a systematic review of postdischarge symptoms (17%).2 The auricular acupuncture procedure was easily performed and was safe, although some patients had minor transitory complaints.

This trial confirms the findings of 2 small studies suggesting the superiority of auricular acupuncture over invasive needle control for analgesia after ambulatory surgery.8,12 Interestingly, in our pilot study12 the ibuprofen requirement in both groups was higher than in the present investigation, probably because of a higher rate of painful arthroscopic procedures. A potentially painful lateral release procedure was performed in 7 (39%) of 18 patients in the pilot study12 but only 22 (18%) of 120 in the present investigation. The withdrawal rate of 12% in the present study can be explained by the time of randomization, before general anesthesia. This rate is at the lower limit of the withdrawal rates for other acupuncture studies for postoperative pain relief (11% to 25%).12,13,17 To avoid dropouts due to change in type of surgery, it would be expedient to perform randomization after the surgical procedure, in the recovery room. However, we chose not to perform acupuncture after surgery, because of experimental and clinical reports indicating that administration of anesthetic before acupuncture weakens or annuls the effects of acupuncture.18,19

The study protocol was based on expert recommendations,20 which follow CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines with specific requirements for acupuncture studies. The routine general anesthesia procedure, with monitoring of depth of anesthesia and patients' core temperature, was performed to minimize the influence of intraoperative factors on postoperative pain.21 Patients, perioperative medical staff and evaluators were blinded to group allocation to minimize potential bias. The patients had similar lesions and operative procedures and hence were expected to have a similar level of pain; we were therefore able to use standardized instead of individualized auricular acupuncture, which assured the methodological quality of the trial.22

The requirement for analgesia during a period of at least 24 hours after surgery, which has been recommended as one of the optimal measures for acute pain,23 was the primary outcome measure in the present study. If all patients receive analgesic medication ad libitum and report adequate pain relief, this is a reliable and ethical method to assess pain relief. Although the patients were successfully blinded to group assignment, self-reporting of the amount of analgesics taken (the primary outcome measure) may represent a study limitation.

The specificity of the acupuncture points has for decades been a crucial question in trials examining the effectiveness of acupuncture.9 The standard control procedure — intradermal insertion of needles in non-acupuncture (sham) points — stimulates the neural pathways of diffuse noxious inhibitory control.24 Under clinical conditions, invasive needle control was reported to have an analgesic effect in 40% to 50% of patients, whereas true acupuncture had this effect in 70% of patients.16 We restricted our study to 2 groups, true acupuncture and sham acupuncture, and questions about the extent of the genuine clinical and placebo (purely psychological) effects of auricular acupuncture remain beyond the scope of our study. Given the cost of treating the side effects of commonly used nonopioid analgesics,25 determining the cost-effectiveness of auricular acupuncture might be an interesting question for a future trial.

In conclusion, this study has shown that auricular acupuncture applied to specific acupuncture points reduced the requirement for ibuprofen relative to invasive needle control after ambulatory arthroscopic knee surgery. To assess the genuine clinical effectiveness of auricular acupuncture, this method must now be compared with standard therapy.

@ See related article page 193

Acknowledgments

We thank Martina Groth and Claudia Scheltz for help in developing the study design and for perioperative management of patients, Dagmar Edinger and Gerd Plock for recruitment of patients and Vasyl Gizhko for statistical advice (all from the Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine Department, Ernst Moritz Arndt University, Greifswald, Germany). The German Medical Society of Acupuncture supported the acquisition and analysis of the data and the writing of the manuscript with a grant to the Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine Department, Ernst Moritz Arndt University. Philips Medical Systems, Boeblingen, Germany, provided the system for monitoring depth of anesthesia, including the disposable sensors.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All authors participated in developing the study design and revising the manuscript and gave final approval for its publication. In addition, Drs. Kuchling and Hofer participated in acquisition of data; Drs. Witstruck, Hofer and Merk provided orthopedic expertise; Drs. Usichenko and Witstruck provided acupuncture expertise; Drs. Pavlovic, Lehmann and Wendt assisted with the statistical analysis and interpretation of data; and Drs. Usichenko, Kuchling, Zach and Wendt provided study supervision.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Taras I. Usichenko, Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, Ernst Moritz Arndt University, Greifswald, Friedrich Loeffler Strass 23b, 17487 Greifswald, Germany; fax +49 3834865802; taras@uni-greifswald.de

REFERENCES

- 1.Pregler J, Kapur P. The development of ambulatory anesthesia and future challenges. Anesthesiol Clin North Am 2003;21:207-28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Wu CL, Berenholtz SM, Pronovost PJ, et al. Systematic review and analysis of postdischarge symptoms after outpatient surgery. Anesthesiology 2002;96:994-1003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.McGrath B, Elgendy H, Chung F, et al. Thirty percent of patients have moderate to severe pain 24 hr after ambulatory surgery: a survey of 5,703 patients. Can J Anesth 2004;51:886-91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Coley KC, Williams BA, DaPos SV, et al. Retrospective evaluation of unanticipated admissions and readmissions after same day surgery and associated costs. J Clin Anesth 2002;14:349-53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Pavlin DJ, Chen C, Penaloza DA, et al. Pain as a factor complicating recovery and discharge after ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg 2002;95:627-34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Shang AB, Gan TJ. Optimising postoperative pain management in the ambulatory patient. Drugs 2003;63:855-67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Wang SM, Peloquin C, Kain ZN. The use of auricular acupuncture to reduce preoperative anxiety. Anesth Analg 2001;93:1178-80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Vorobiev VV, Dymnikov AA. [The effectiveness of auricular microneedle acupuncture at the early postoperative period under conditions of the day surgical department.] Vestn Khir im II Grek 2000;159:48-50. Russian. [PubMed]

- 9.Moore A, McQuay H. Acupuncture: Not just needles? Lancet 2005;366:100-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Margolin A, Kleber HD, Avants SK, et al. Acupuncture for the treatment of cocaine addiction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;287:55-63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Bullock ML, Kiresuk TJ, Sherman RE, et al. A large randomized placebo controlled study of auricular acupuncture for alcohol dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat 2002;22:71-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Usichenko TI, Hermsen M, Witstruck T, et al. Auricular acupuncture for pain relief after ambulatory knee arthroscopy — a pilot study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2005;2:185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Usichenko TI, Dinse M, Hermsen M, et al. Auricular acupuncture for pain relief after total hip arthroplasty — a randomized controlled study. Pain 2005;114:320-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Chung F, Chan VW, Ong D. A post-anesthetic discharge scoring system for home readiness after ambulatory surgery. J Clin Anesth 1995;7:500-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Alimi D, Rubino C, Pichard-Leandri E, et al. Analgesic effect of auricular acupuncture for cancer pain: a randomized, blinded, controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:4120-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Lewith GT, Machin D. On the evaluation of the clinical effects of acupuncture. Pain 1983;16:111-27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Sakurai M, Suleman MI, Morioka N, et al. Minute sphere acupressure does not reduce postoperative pain or morphine consumption. Anesth Analg 2003;96:493-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Eriksson SV, Lundeberg T, Lundeberg S. Interaction of diazepam and naloxone on acupuncture induced pain relief. Am J Chin Med 1991;19:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Vickers AJ. Can acupuncture have specific effects on health? A systematic review of acupuncture antiemesis trials. J R Soc Med 1996;89:303-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.MacPherson H, White A, Cummings M, et al. Standards for reporting interventions in controlled trials of acupuncture: the STRICTA recommendations. Complement Ther Med 2001;9:246-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Doufas AG. Consequences of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2003;17:535-49. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Patel M, Gutzwiller F, Paccaud F, et al. A meta-analysis of acupuncture for chronic pain. Int J Epidemiol 1989;18:900-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Barden J, Edwards JE, Mason L, et al. Outcomes in acute pain trials: systematic review of what was reported? Pain 2004;109:351-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Le Bars D, Dickenson AH, Besson JM. Diffuse noxious inhibitory controls (DNIC). I. Effects on dorsal horn convergent neurones in the rat. Pain 1979;6:283-304. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Sturkenboom MC, Romano F, Simon G, et al. The iatrogenic costs of NSAID therapy: a population study. Arthritis Rheum 2002;47:132-40. [DOI] [PubMed]