The 2006 edition of the Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) is available online (at www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/std-mts/sti_2006/sti_intro2006_e.html) and in hard copy from the Canadian Public Health Association. For this edition, revision and chapter review followed an even more rigorous process, including literature review, STI expert rewrite and at least 4 rounds of blinded expert review — 3 rounds within the expert working group and another by 2 or more reviewers external to that group. Moreover, this edition indicates the level of recommendation and the quality of evidence for treatment options.

Over the past decade, increases have been reported in the incidences of 3 nationally reported STIs: chlamydia, gonorrhea and infectious syphilis. The 2006 guidelines emphasize that both primary and secondary STI prevention strategies are needed if incidences are to decrease. Primary prevention is aimed at preventing exposure by identifying at-risk individuals, performing a thorough assessment accompanied by patient-centred counselling and education, and immunization (e.g., for human papillomavirus infections, hepatitis A or B), when appropiate. Secondary prevention is aimed at preventing or limiting further spread by decreasing the prevalence of STIs through detection in at-risk populations, counselling, conducting partner notification and treating infected individuals and contacts. Front-line clinicians have key roles in both primary and secondary prevention.

The 2006 edition includes 3 new chapters. The one on primary care and STIs outlines practices for primary care professionals for STI prevention, counselling, screening, diagnosis, clinical management, reporting to public health and partner notification. A chapter on specific STIs includes descriptions of chancroid and lymphogranuloma venereum. Another discusses increased risks in specific populations such as immigrants and refugees, inmates and offenders, sex workers, men who have sex with men, women who have sex with women, and substance users.

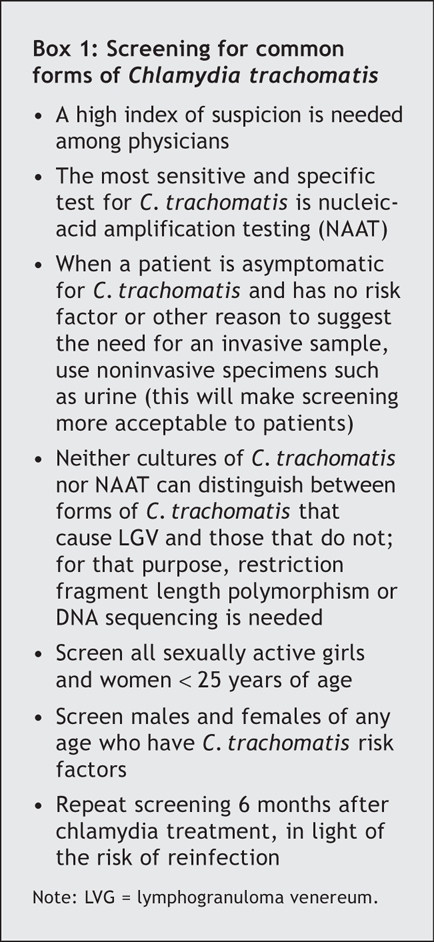

Highlights for specific STIs are also included in the new edition. For HIV, for example, the risks of transmission and acquisition are increased many times over when any of several other STIs such as syphilis and herpes simplex are present. For routine Chlamydia trachomatis infections, the guidelines emphasize the importance of screening all sexually active females under 25 years of age and all people (either sex, any age) who have risk factors for chlamydia infection (Box 1). The value of repeat screening 6 months after chlamydia treatment in light of the risk of reinfection is also highlighted.1,2

Box 1.

The serotypes of C. trachomatis that cause lymphogranuloma venereum (serotypes or serovars L1, 2 and 3) have until recently been relatively rare in Canada. These infections had been limited to sexual acquisition in the tropics, but there have been recent outbreaks of this rare form of C. trachomatis in Canada, as well as in Western Europe and the United States, with endemic transmission primarily among men who have sex with men who also have proctocolitis and inguinal or femoral lympadenopathy. Such outbreaks among men who have sex with men have been associated with concurrent infection with HIV, other STIs and acute hepatitis C, and with traumatic anal sex.

In Neisseria gonorrhoeae, the rate of quinolone resistance has been rising in many parts of the world, including the United States and parts of Canada. Quinolone therapy is not recommended, even in cases of pelvic inflammatory disease, whenever gonorrhea cases or contacts are epidemiologically linked to areas where the incidence of quinolone-resistant N. gonorrhoeae is above 3%– 5%. Repeat screening 6 months after gonorrhea treatment is recommended because of the high risk of reinfection.3,4

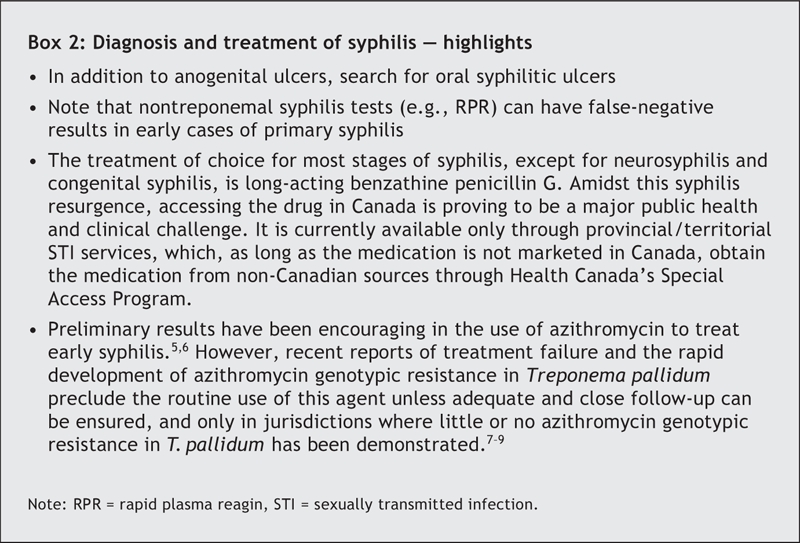

Of particular note for syphilis, there have been multiple outbreaks in different parts of Canada during the past decade. Physicians need a higher index of suspicion than previously (Box 2).5–9

Box 2.

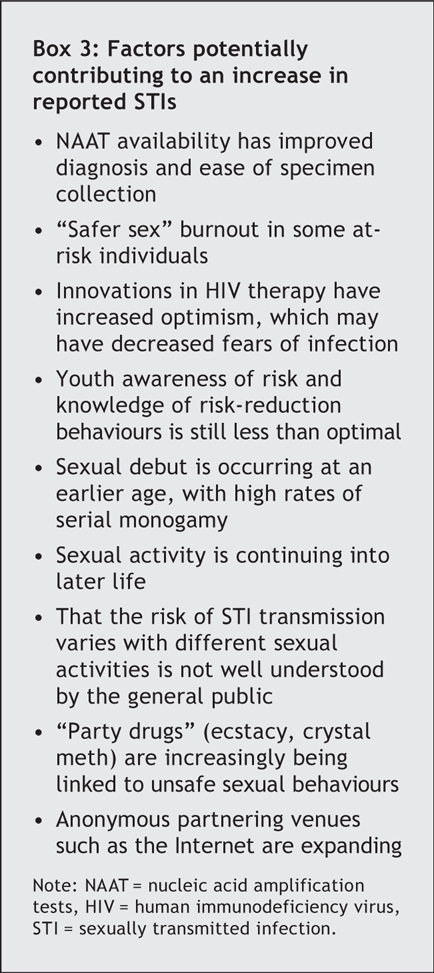

Rates of reported STIs have not decreased since the late 1990s; the need to strengthen STI prevention is clear. Box 3 lists potential factors that have been suggested for the increases in chlamydia, gonorrhea and infectious syphilis. Primary health care providers are strategically placed to play an important role in the prevention, detection and management of STIs.

Box 3.

Given the increases in reported STIs with resurgence of old foes such as syphilis and escalating problems with chlamydia and HIV infections, this is an opportune time for public health and clinical professionals to join together in the fight to get the STI epidemic under control.

Noni MacDonald Division of Infectious Diseases IWK Health Centre Halifax, NS Tom Wong Division of Community Acquired Infections Public Health Agency of Canada Ottawa, Ont.

Figure.

Photo by: iStockphoto

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rietmeijer CA, Van BR, Judson FN, et al. Incidence and repeat infection rates of Chlamydia trachomatis among male and female patients in an STD clinic: implications for screening and rescreening. Sex Transm Dis 2002;29:65-72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Whittington WL, Kent C, Kissinger P, et al. Determinants of persistent and recurrent Chlamydia trachomatis infection in young women: results of a multicenter cohort study. Sex Transm Dis 2001;28:117-23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Bernstein KT, Zenilman J, Olthoff G, et al. Gonorrhea reinfection among sexually transmitted disease clinic attendees in Baltimore, Maryland. Sex Transm Dis 2006;33:80-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.De P, Singh AE, Wong T, et al. Predictors of gonorrhea reinfection in a cohort of sexually transmitted disease patients in Alberta, Canada, 1991–2003. Sex Transm Dis DOI: 10.1097/01.olq.0000230485.85132.e9. Epub 2006 Jul 27 ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Riedner G, Rusizoka M, Todd J, et al. Single-dose azithromycin versus penicillin G benzathine for the treatment of early syphilis. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1236-44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Hook EW 3rd, Martin DH, Stephens J, et al. A randomized, comparative pilot study of azithromycin versus benzathine penicillin G for treatment of early syphilis. Sex Transm Dis 2002;29:486-90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Lukehart SA, Godornes C, Molini BJ, et al. Macrolide resistance in Treponema pallidum in the United States and Ireland. N Engl J Med 2004;351:154-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Mitchell SJ, Engelman J, Kent CK, et al. Azithromycin-resistant syphilis infection: San Francisco, California, 2000–2004. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:337-45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Morshed MG, Jones HD. Treponema pallidum macrolide resistance in BC. CMAJ 2006;174(3):349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]