Abstract

Medical expulsion therapy has been shown to be a useful adjunct to observation in the management of ureteral stones. Alpha-1-adrenergic receptor antagonists have been studied in this role. Alpha-1 receptors are located in the human ureter, especially the distal ureter. Alpha-blockers have been demonstrated to increase expulsion rates of distal ureteral stones, decrease time to expulsion, and decrease need for analgesia during stone passage. Alpha-blockers promote stone passage in patients receiving shock wave lithotripsy, and may be able to relieve ureteral stent-related symptoms. In the appropriate clinical scenario, the use of α-blockers is recommended in the conservative management of distal ureteral stones.

Key words: Alpha-blockers, Ureteral stones, Kidney stones

Recent advances in endoscopic stone management have allowed kidney stones to be treated using minimally invasive techniques, which have increased success rates and decreased treatment-related morbidity. These advances include shock wave lithotripsy (SWL), ureteroscopy, and percutaneous nephrostolithotomy. Although these approaches are less invasive than traditional open surgical approaches, they are expensive and have inherent risks. Consequently, observation has been advocated for small ureteral stones with a high probability to pass that do not have absolute indications for surgical intervention. The rate of spontaneous passage with no medical intervention for a stone of 5 mm or smaller in the proximal ureter is estimated to be 29% to 98%, and in the distal ureter, 71% to 98%. The most important factors in predicting the likelihood of spontaneous stone passage are stone location and stone size.1

Recently, medical expulsion therapy (MET) has been investigated as a supplement to observation in an effort to improve spontaneous stone passage rates, which can be unpredictable. Because ureteral edema and ureteral spasm have been postulated to affect stone passage, these effects have been targeted for pharmacologic intervention. Therefore, the primary agents that have been evaluated for MET are calcium channel blockers, steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and α1-adrenergic receptor antagonists. A recent meta-analysis was performed, looking at studies that compared stone passage rates in patients who were given calcium channel blockers or α1-adrenergic receptor antagonists versus controls who did not receive these medications. The analysis demonstrated a 65% greater chance of passing a ureteral stone in patients who received either medication.2 The use of these drugs for the purposes of facilitating stone passage, however, is investigational and off label. This article will focus on the use of α-blockers in the management of stone disease and other stone-related processes.

Physiology

The human ureter contains α-adrenergic receptors along its entire length, with the highest concentration in the distal ureter.3,4 Stimulation of the α receptors increases the force of ureteral contraction and the frequency of ureteral peristalsis, whereas antagonism of the receptors has the opposite effects. Malin and colleagues first demonstrated the presence of α-adrenergic receptors in the human ureter in 1970.3 These investigators obtained specimens containing all levels of the human ureter. In the lower third of the ureter, exposure to adrenaline or noradrenaline increased the tone and frequency of contractions, whereas exposure to isoproterenol decreased the amplitude and frequency of contractions. Similar results were seen when the entire length of the ureter was exposed to adrenaline and noradrenaline. This demonstrated the presence of α-adrenergic receptors along the entire length of the ureter, as well as the physiologic response of increased tone and frequency of contractions in the ureter when exposed to α-adrenergic agonists.3

In a study using dog and rabbit ureters, Weiss and associates demonstrated that α-adrenergic agonists have a stimulatory effect on the ureteral smooth muscle, whereas β-adrenergic agonists have an inhibitory affect. Phenylephrine was found to significantly increase the contractile force of ureteral segments. This effect was blocked by pretreatment of the segment with phentolamine, an α-adrenergic antagonist. Additionally, when rabbit ureters were exposed to electrical stimuli in the presence of phentolamine, there was a decrease in maximum force generated.5 When dog ureters were exposed to different compounds, including α agonists and antagonists, phentolamine caused a 67% prolongation of ureteral peristaltic discharge intervals, an 84% increase in ureteral fluid bolus volume, and an 18% increase in the rate of fluid transportation.6

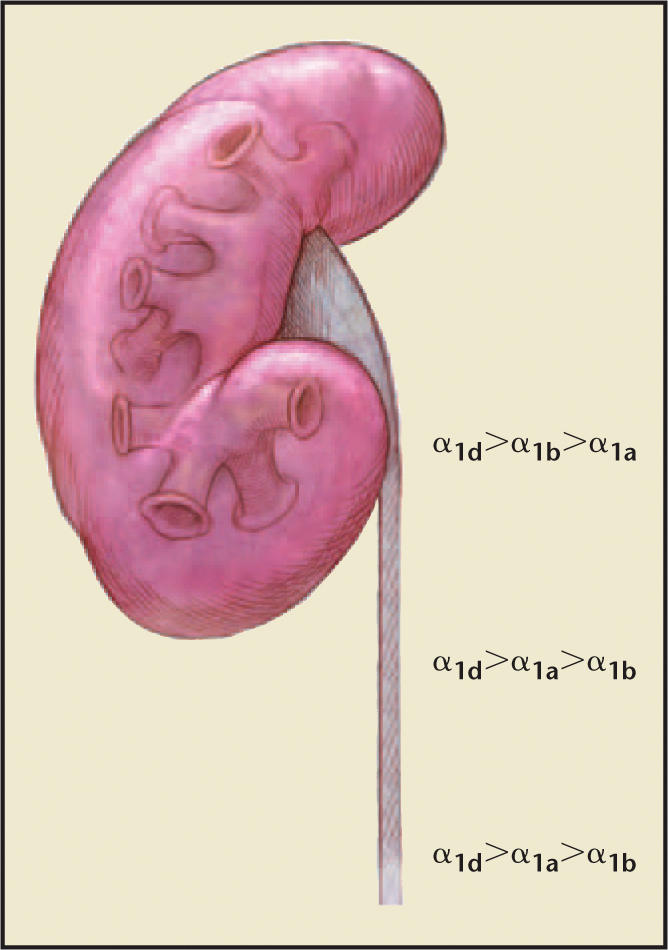

More recently, Sigala and colleagues4 studied α1-adrenergic receptor gene and protein expression in the proximal, middle, and distal ureter. They demonstrated that the distal ureter expressed the greatest quantity of α1 messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA). The α1d mRNA was expressed in all portions of the ureter, and it was expressed in significantly greater amounts than the α1a or α1b receptor subtype in both the proximal and distal ureter. Using ligand binding, they were able to show that the distal ureter had the highest density of α receptors, and α1d was the most common receptor present in all portions of the ureter (Figure 1). An in vitro study comparing the effects of nifedipine, a calcium channel blocker; diclofenac, an NSAID; and 5-methylurapidil (5-MU), an α1a antagonist, demonstrated that both nifedipine and 5-MU decreased the force of contraction in ureteral segments. The predominant affect of 5-MU was found to be in the distal ureter.7

Figure 1.

Representation of the kidney and ureter with density of α receptors as studied by Sigala et al.4 Alpha-1d receptor is the most common in all segments of the ureter. The highest overall density of α1 receptors is in the distal ureter.

Treatment of Distal Ureteral Stones

MET has been aimed at modifiable factors that can affect stone passage. These factors are mucosal edema/inflammation, infection, and ureteral spasm. Several agents have been studied as potential MET. Steroids have been used to reduce mucosal edema and aid in stone passage. A recent study by Porpiglia and associates8 failed to demonstrate that steroids alone promote stone passage. However, Dellabella and colleagues9 did show that steroids are a useful adjunct to induce more rapid stone expulsion. They found similar expulsion rates when tamsulosin was used alone or with deflazacort (90% vs 96.7%), but found significantly reduced time to expulsion in the group of patients who also received steroids (120 hours vs 72 hours; P = .036). NSAIDs also have the potential to decrease inflammation and mucosal edema and are useful for analgesia during stone passage, but have not been proven to be successful in stone passage when used alone.10 Nifedipine is the most studied calcium channel blocker used to treat ureteral spasm and promotes stone passage.11–13

Alpha-1-adrenergic receptor antagonists have some degree of selectivity for the detrusor and the distal ureter and have therefore been the next agents investigated for their potential to promote stone expulsion and decrease pain. The likely mechanism that α-blockers use in stone passage has been to reduce ureteral spasm, increase pressure proximal to the stone, and relax the ureter in the region of and distal to the stone.14 The rationale in using α1 antagonists in MET has been that they are capable of decreasing the force of ureteral contraction, decreasing the frequency of peristaltic contractions, and increasing the fluid bolus volume transported down the ureter.5–7

In 1972, Kubacz and Catchpole15 compared the effectiveness of treating ureteral colic with meperidine, phentolamine, and propanolol. They found that 85.5% of patients receiving meperidine, 63.5% of patients receiving phentolamine, and only 6% of patients receiving propanolol had significant relief of pain. Interestingly, they found that in 4 patients receiving phentolamine, their renal obstruction was corrected, as depicted by intravenous pyelography, as was their pain. The investigators concluded that α-adrenergic blockade may have the advantage of relieving obstruction as well as pain.

Tamsulosin has been the most commonly studied α1-blocker in the treatment of ureteral stones; however, the data have been extrapolated and clinically tested on other α-blockers as well. Tamsulosin has equal affinity for α1a and α1d receptors.16 The α1d receptor is the most common receptor in the ureter and is most concentrated in the distal ureter.4 Cervenakov and associates17 performed one of the first double-blind, randomized studies comparing their standard MET with and without tamsulosin (Table 1). Their standard therapy included an injection of a narcotic and diazepam on presentation, followed by a daily NSAID. They found that the spontaneous passage rates with and without tamsulosin were 80.4% versus 62.8%, respectively. The majority of patients receiving tamsulosin passed their stone within 3 days. There were fewer instances of recurrent colic with tamsulosin, and the tamsulosin was well tolerated.

Table 1.

Rates of Stone Expulsion for Distal Ureteral Stones in Patients Treated With Alpha-1-Blocker Versus Patients Treated With Standard Medical Expulsion Therapy Without Alpha-1-Blocker

| Distal Ureteral Stone Expulsion Rates (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| With Alpha-1- | Without Alpha-1- | ||

| Study | Blocker | Blocker | P Value |

| Cervenakov I et al17 | 80.4 | 62.8 | N/A |

| Dellabella M et al18 | 100 | 70 | .001 |

| Resim S et al19 | 86.6 | 73.3 | .196 |

| De Sio M et al20 | 90 | 58.7 | .01 |

| Yilmaz E et al21 | 79.31 (tamsulosin) | 53.57 | .03 |

| 78.57 (terazosin) | 53.57 | .03 | |

| 75.86 (doxazosin) | 53.57 | .04 | |

| Porpiglia F et al22 | 85 | 43 | <.001 |

| Dellabella M et al23 | 97.1 | 64.3 | <.0001 |

Tamsulosin increases rates of spontaneous stone expulsion and decreases the time to stone expulsion (Tables 1 and 2). Importantly, it decreases the amount of pain patients suffer while passing their stones (Table 3). Dellabella and colleagues18 evaluated 60 patients with symptomatic ureterovesical junction stones. They compared 2 groups of 30 patients each: 1 group received tamsulosin and the other received floroglucine-trimetossibenzene, a spasmolytic used in Italy. All patients received an oral steroid (deflazacort) for 10 days, clotrimoxazole for 8 days, and diclofenac as needed. The expulsion rate was 100% for patients receiving tamsulosin, compared with 70% in the other group. The time to expulsion was significantly less in the tamsulosin group, 65.7 hours compared with 111.1 hours in the group not using tamsulosin. Patients receiving tamsulosin required significantly fewer injections of diclofenac, 0.13 compared with 2.83. One third of the patients who did not receive tamsulosin needed to be hospitalized, 3 for uncontrollable pain and 7 for failure to pass their stone in 28 days. Mean stone size was significantly greater in the group receiving tamsulosin, 6.7 mm versus 5.8 mm in those who received floroglucine, which further points to the effectiveness of α-blockers.

Table 2.

Time to Stone Expulsion for Distal Ureteral Stones in Patients Treated With Alpha-1-Blocker Versus Patients Treated With Standard Medical Expulsion Therapy Without Alpha-1-Blocker

| Distal Ureteral Stone Expulsion Times |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | With Alpha-1 Blocker | Without Alpha-1 Blocker | P Value |

| Dellabella M et al18 | 65.7 h | 111.1 h | .02 |

| De Sio M et al20 | 4.4 d | 7.5 d | .005 |

| Yilmaz E et al21 | 6.31 d (tamsulosin) | 10.54 d | .04 |

| 5.75 d (terazosin) | 10.54 d | .03 | |

| 5.93 d (doxazosin) | 10.54 d | .03 | |

| Porpiglia F et al22 | 7.9 d | 12 d | .02 |

| Dellabella M et al23 | 72 h | 120 h | <.0001 |

Table 3.

Diminished Pain During Stone Passage With Alpha-1 Blocker

| Pain Measure | |

|---|---|

| Significantly | |

| Improved With | |

| Study | Alpha-1-Blocker* |

| Dellabella M et al18 | Yes |

| Resim S et al19 | Yes |

| De Sio M et al20 | Yes |

| Yilmaz E et al21 | Yes |

| Porpiglia F et al22 | Yes |

| Dellabella M et al23 | Yes |

Various measures were used to quantify pain in the above studies, including visual analogue scale, dose of diclofenac in milligrams, number of injections of diclofenac used, and number of episodes of colic.

Patients with distal ureteral stones given tamsulosin reported decreased pain using a visual analogue scale (VAS). Resim and colleagues19 studied 60 patients with lower ureteral stones who were divided into 2 groups, 1 of which received tenoxicam, an NSAID, and another group that received tamsulosin in addition to tenoxicam. The stones ranged in size from 5 to 12 mm in the group without tamsulosin and from 5 to 13 mm in the group receiving tamsulosin. Patients receiving tamsulosin reported significantly less pain using a VAS scoring from 1 to 10 (5.70 vs 8.30; P < .0001). Patients receiving tamsulosin reported fewer instances of colic. The spontaneous passage rates were 86.6% for patients receiving tamsulosin, compared with 73.3% for those who did not. There were minimal side effects reported from the tamsulosin, and none of the patients had to stop taking tamsulosin secondary to a side effect.

In a more recent prospective study, De Sio and associates20 showed similar results. They enrolled 96 patients with distal ureteral stones smaller than 10 mm. The patients were randomized into 2 groups: 1 group receiving diclofenac and aescin, an anti-edema extract from horse chestnuts, and the second group receiving tamsulosin in addition to diclofenac and aescin. The stone expulsion rate was 90.0% with tamsulosin and 58.7% without tamsulosin. The time to expulsion was significantly less with tamsulosin: 4.4 days versus 7.5 days. Patients receiving tamsulosin required significantly less analgesia. The rate for rehospitalization for patients receiving tamsulosin was 10%, and none of the patients required an endoscopic procedure, whereas in the group who did not receive tamsulosin, 27.5% were rehospitalized and 13% underwent an endoscopic procedure.

Although tamsulosin has been the most commonly studied α1-blocker in the treatment of ureteral stones, other α1 antagonists have been shown to be equally effective. In a prospective randomized study, tamsulosin was compared with terazosin and doxazosin. A total of 114 patients with distal ureteral stones of 10 mm or smaller were divided into 4 treatment groups: those who received either no α1-blocker (control group), tamsulosin 0.4 mg, terazosin 5 mg, or doxazosin 4 mg. All the patients were given diclofenac to take as needed for pain. In the control group, only 53.57% passed their stones, whereas the rates for the groups receiving tamsulosin, terazosin, and doxazosin were 79.31%, 78.57%, and 75.86%, respectively. The patients treated with α1-blockers also reported significantly decreased pain and need for analgesia when compared with the control group. Finally, the mean times to passage for the control group, and the groups receiving tamsulosin, terazosin, and doxazosin were 10.54 days, 6.31 days, 5.75 days, and 5.93 days, respectively. The mean time to passage was significantly lower in the groups receiving α1-blockers compared with the control group. Of note, there were no instances of hypotension in any of the patients receiving α1-blockers, and the patients receiving terazosin and doxazosin were started on their therapeutic doses upon entrance into the study rather than being titrated to those doses.21

Alpha-1-Blockers Compared With Calcium Channel Blockers

In 1994, Borghi and colleagues demonstrated the efficacy of the calcium channel blocker nifedipine in the treatment of ureteral stones in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study.11 They enrolled 86 patients to receive methylprednisolone with placebo or nifedipine. The patients receiving nifedipine had a significantly higher rate of stone passage compared with the placebo group, 87% versus 65%. Studies comparing nifedipine with tamsulosin have shown that both are effective in aiding in stone passage, but that tamsulosin may be more efficacious.22,23

In a study of 86 patients with distal ureteral stones smaller than 1 cm, Porpiglia and associates22 compared the effectiveness of nifedipine and tamsulosin. All 86 patients received 10 days of deflazacort. The 86 patients were broken down into 3 groups: 1 group received only deflazacort (control group), 1 group received tamsulosin 0.4 mg daily, and the third group received 30 mg nifedipine slow release daily. All patients received diclofenac as needed for pain. The expulsion rates for the control group, tamsulosin group, and nifedipine group were 43%, 85%, and 80%, respectively. Both tamsulosin and nifedipine significantly increased stone passage rates. Only tamsulosin had a significantly shorter time to stone passage when compared with the control group. The mean time to passage for the control group, tamsulosin group, and nifedipine group was 12 days, 7.9 days, and 9.3 days, respectively. Both tamsulosin and nifedipine significantly reduced the need for diclofenac when compared with the control group. The investigators concluded that tamsulosin was superior to nifedipine because of the decreased time to expulsion and slightly higher rate of expulsion, even though the stone size in the tamsulosin group was larger, although not statistically significantly so (5.42 mm vs 4.7 mm).

Dellabella and colleagues also recently compared tamsulosin, nifedipine, and phloroglucinol, a spasmolytic agent, in 210 patients with distal ureteral stones larger than 4 mm.23 The patients were randomly assigned to receive either tamsulosin 0.4 mg, nifedipine slow release 30 mg, or phloroglucinol. All patients received 10 days of deflazacort 30 mg and 8 days of cotrimoxazole, as well as diclofenac as needed. The percentage of stones passed was significantly greater in the group receiving tamsulosin (97.1%) when compared with both the group receiving nifedipine (77.1%) and the group receiving phloroglucinol (64.3%). The median time in hours to stone passage was 72 hours for the group receiving tamsulosin, and this was significantly less than the 120 hours for the groups receiving nifedipine or phloroglucinol. None of the patients receiving tamsulosin required hospitalization during the study, whereas 15.7% of the patients receiving phloroglucinol and 4.3% of the patients receiving nifedipine required hospitalization during the study. The group receiving tamsulosin required significantly fewer endoscopic procedures, required less analgesia, and lost fewer workdays when compared with the groups receiving nifedipine or phloroglucinol. At the conclusion of the study, patients filled out a EuroQuol questionnaire to evaluate quality of life, and tamsulosin was shown to have significantly improved quality of life variables such as mobility, capacity to perform usual activities, pain and discomfort, and anxiety. Of note, the median stone size in the tamsulosin group was significantly larger, 7 mm compared with 6 mm in the other 2 groups.

Alpha-1-Blockers and SWL

SWL has been established as an effective therapy for the treatment of ureteral and renal stones. Tamsulosin has been studied as an adjunct therapy along with SWL. One study compared the stone-free rate in 48 patients who received SWL for distal ureteral stones of 6 mm to 15 mm.24 After the patients underwent SWL, they were randomized to receive either oral hydration and diclofenac, or oral hydration and diclofenac with tamsulosin 0.4 mg. The mean stone size for those receiving tamsulosin was 8.6 mm, compared with 8.2 mm for those not receiving tamsulosin. Patients were evaluated 15 days after receiving SWL with abdominal radiography to evaluate for residual stone burden. The stone-free rate was 70.8% for patients who received tamsulosin, compared with 33.3% for those who did not (P = .019). Only 1 patient receiving tamsulosin experienced slight dizziness. The investigators concluded that tamsulosin could improve stone-free rates after SWL of distal ureteral stones with minimal side effects.

Gravina and colleagues studied the efficacy of tamsulosin as an adjunctive therapy after SWL for renal stones.25 They included 130 patients who underwent renal stone SWL, excluding patients with lower pole stones. The stones ranged in size from 4 mm to 20 mm. After SWL, patients were randomized to either receive standard medical therapy, which was methylprednisolone, 16 mg twice daily for 15 days and diclofenac as needed, or standard therapy plus tamsulosin 0.4 mg. Patients were evaluated with renal ultrasound, radiography, and/or intravenous urography at 4, 8, and 12 weeks. Clinical success was defined as stone-free status or the presence of clinically insignificant stone fragments, which were defined as asymptomatic fragments 3 mm or less. At 12 weeks, clinical success was achieved in 78.5% of patients receiving tamsulosin and 60% of patients not receiving tamsulosin (P = .037). Tamsulosin had a greater effect when compared with the control group for larger stones. In stones 4 mm to 10 mm, the clinical success rates with and without tamsulosin were 75% versus 68% (P = .05), and for stones 11 mm to 20 mm the success rates were 81% versus 55% (P = .009). Tamsulosin significantly reduced the amount of diclofenac used and reduced the occurrence of flank pain after SWL. Patients receiving tamsulosin required ureteroscopy or a second SWL less often compared with those who did not receive tamsulosin, but the difference was not statistically significant. The mechanism of action of how α-blockers help clear renal stone burden has yet to be elucidated and requires further investigation; however, their ability to assist in the passage of stone fragments when they pass through the ureter is intuitive, based on previous work as reported.

Steinstrasse is an accumulation of stone fragments in the ureter typically after SWL, which can lead to obstruction. It is estimated to occur in 2% to 10% of cases, and there is increased risk with increasing stone burden.26 Resim and colleagues27 studied the effect of tamsulosin on the resolution of steinstrasse. Patients were included in the study if they had steinstrasse in the lower ureter and if the column of stone fragments was obstructing the ureter, as determined with radiography and renal ultrasound. A total of 67 patients were included and were randomized to receive hydration and tenoxicam, an NSAID, with or without tamsulosin 0.4 mg. Patients were followed for 6 weeks. The stone passage rates were determined by patient report and by imaging with radiography and renal ultrasound. The passage rates were 75% with tamsulosin and 65.7% without, which did not reach statistical significance. The time to passage was also not significantly different. However, patients receiving tamsulosin did have significantly fewer episodes of colic and had significantly lower pain scores on a VAS. Approximately 40% of patients receiving tamsulosin experienced minor side effects from the medication, but none were significant enough for the patient to stop taking the tamsulosin. Although α-blockers did not reach statistical significance in the previous study, they may be a useful adjunct in the management of steinstrasse because there is a trend toward improved resolution of the steinstrasse and there is the potential benefit of improved analgesia.

Alpha-1-Blockers and Ureteral Stents

Ureteral stents are often used in the treatment of renal and ureteral stones. The stents can be associated with some morbidity, including pain and urinary symptoms. Deliveliotis and colleagues studied whether these symptoms could be improved using the α1-blocker alfuzosin.28 Double-J stents were placed in 100 patients for the treatment of ureteral stones smaller than 10 mm. Patients were randomized after stent placement to receive either alfuzosin 10 mg daily or placebo for 4 weeks. At the end of the 4-week study, all patients were assessed for stone-free status and filled out the validated Ureteral Stent Symptom Questionnaire (USSQ). The mean urinary symptom score, as assessed by the USSQ, was significantly lower in the group receiving alfuzosin, 21.6 versus 28.1 (P < .001). Patients receiving alfuzosin reported less stent related pain, 66% versus 44% (P = .027) and also reported a lower mean pain index score, 8 versus 11.4 (P < .001). Both the mean general health index score and mean sexual matters score were significantly better in patients taking alfuzosin. Spontaneous stone passage was similar between the 2 groups. Albeit a single small study, the potential benefits of α-blockers is demonstrated in reducing stent-related symptoms and should be investigated further.

Current Recommendations

When conservative management of a ureteral stone is being considered and the patient has no associated signs of infection, uncontrollable pain, or renal failure, adjuvant pharmacologic intervention has proven efficacious in improving spontaneous stone passage rate and time interval, and in reducing analgesic requirements. Many of the studies have administered the drugs in conjunction with steroids and/or NSAIDs, which may reduce ureteral edema and improve the ability for a patient to spontaneously pass a ureteral stone. However, several of the more recent studies have shown benefit to both α-blockers and calcium channel blockers without the adjunctive use of steroids; furthermore, tamsulosin, in a randomized trial, has been shown to be more efficient than nifedipine with a decreased time to expulsion and slightly higher rate of expulsion.17–23

Our current treatment regimen for conservative management of ureteral stones, particularly distal ureteral stones, is to start an α-adrenergic receptor antagonist, prescribe analgesics as needed, and follow the patient clinically with serial imaging and laboratory studies if needed. However, the combination of corticosteroids with a calcium channel blocker or an α-blocker can also be used with precautions to prevent steroid-related complications.

Summary

Alpha-1-adrenergic receptors are located throughout the human ureter. The physiologic response to antagonism of these receptors is decreased force of contraction, decreased peristaltic frequency, and increased fluid bolus volume transported down the ureter. These responses are likely how α-blockers assist in ureteral stone passage. Alpha-blockers, specifically α1 antagonists, are highly effective in increasing the expulsion rate of distal ureteral stones, reducing the time to stone passage, and decreasing the amount of pain medication needed during passage stones (see Tables 1–3). Alpha blockers may also be a useful adjunct in the treatment of both ureteral and renal stones with SWL. They may also reduce the urinary symptoms and pain associated with double-J ureteral stents. Further investigation is necessary to define the role of α-blockers in the treatment of proximal ureteral and renal stones, and to elucidate the potential mechanisms of renal stone clearance after surgical stone intervention.

Although success has been shown with calcium channel blockers with or without steroids and/or NSAIDs, α-blockers, with their high success rates, excellent safety profile, low side effect profile, and ease of use, have become the leading candidate in MET and should be used as first-line therapy in any appropriate candidate on an observation protocol during the passage of a distal ureteral stone. Additionally, α-adrenergic receptor antagonists may be considered during the conservative treatment of proximal and mid-ureteral stones, and after surgical intervention of renal stones.

Main Points.

Medical expulsion therapy is a useful adjunct to observation in the conservative management of ureteral stones.

Alpha-1 receptors are located in the human ureter, especially the distal ureter; α-blockers increase expulsion rates of distal ureteral stones, decrease time to expulsion, and decrease need for analgesia during stone passage.

In the appropriate clinical scenario, the use of α-blockers is recommended in the conservative management of distal ureteral stones.

References

- 1.Segura JW, Preminger GM, Assimos DG, et al. Ureteral stones clinical guidelines panel summary report on the management of ureteral calculi. J Urol. 1997;158:1915–1921. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)64173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hollingsworth JM, Rogers MAM, Kaufman SR, et al. Medical therapy to facilitate urinary stone passage: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2006;368:1171–1179. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69474-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malin JM, Deane RF, Boyarsky S. Characterisation of adrenergic receptors in human ureter. Br J Urol. 1970;42:171–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1970.tb10018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sigala S, Dellabella M, Milanese G, et al. Evidence for the presence of alpha1 adrenoceptor subtypes in the human ureter. Neurourol Urodynamics. 2005;24:142–148. doi: 10.1002/nau.20097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss RM, Bassett AL, Hoffman BF. Adrenergic innervation of the ureter. Invest Urol. 1978;16:123–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morita T, Wada I, Saeki H, et al. Ureteral urine transport: changes in bolus volume, peristaltic frequency, intraluminal pressure and volume of flow resulting from autonomic drugs. J Urol. 1987;137:132–135. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)43904-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davenport K, Timoney AG, Keeley FX. A comparative in vitro study to determine the beneficial effect of calcium-channel and alpha(1)-adrenoceptor antagonism on human ureteric activity. BJU Int. 2006;98:651–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Porpiglia F, Vaccino D, Billia M, et al. Corticosteroids and tamsulosin in the medical expulsive therapy for symptomatic distal ureter stones: single drug or association? Eur Urol. 2006;50:339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dellabella M, Milanes G, Muzzonigro G. Medical-expulsive therapy for distal ureterolithiasis: randomized prospective study on role of corticosteroids used in combination with tamsulosin-simplified treatment regimen and health-related quality of life. Urology. 2005;66:712–715. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laerum E, Ommundsen OE, Gronseth JE, et al. Oral diclofenac in the prophylactic treatment of recurrent renal colic. A double-blind comparison with placebo. Eur Urol. 1995;28:108–111. doi: 10.1159/000475031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borghi L, Meschi T, Amato F, et al. Nifedipine and methylprednisolone in facilitating ureteral stone passage: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Urol. 1994;152:1095–1098. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32511-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porpiglia F, Destefanis P, Fiori C, Fontanta D. Effectiveness of nifedipine and deflazacort in the management of distal ureter stones. Urology. 2000;56:579–582. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00732-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porpiglia F, Destefanis P, Fiori C, et al. Role of adjunctive medical therapy with nifedipine and deflazacort after extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy of ureteral stones. Urology. 2002;59:835–838. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01553-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss RM. Physiology and pharmacology of the renal pelvis and ureter. In: Walsh PC, Retik AB, Vaughan Jr, Wein AJ, editors. Campbell’s Urology. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002. pp. 399–400. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubacz GJ, Catchpole BN. The role of adrenergic blockade in the treatment of ureteral colic. J Urol. 1972;107:949–951. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)61178-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richardson CD, Donatucci CF, Page SO, et al. Pharmacology of tamsulosin: saturation-binding isotherms and competition analysis using cloned alpha 1-adrenergic receptor subtypes. Prostate. 1997;33:55–59. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19970915)33:1<55::aid-pros9>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cervenakov I, Fillo J, Mardiak J, et al. Speedy elimination of ureterolithiasis in lower part of ureters with the alpha 1-blocker tamsulosin. Int Urol Nephrol. 2002;34:25–29. doi: 10.1023/a:1021368325512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dellabella M, Milanese G, Muzzonigro G. Efficacy of tamsulosin in the medical management of juxtavesical ureteral stones. J Urol. 2003;170:2202–2205. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000096050.22281.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Resim S, Ekerbicer H, Ciftci A. Effect of tamsulosin on the number and intensity of ureteral colic in patients with lower ureteral calculus. Int J Urol. 2005;12:615–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2005.01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Sio M, Autorino R, Di Lorenzo G, et al. Medical expulsive treatment of distal-ureteral stones using tamsulosin: a single-center experience. J Endourol. 2006;20:12–16. doi: 10.1089/end.2006.20.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yilmaz E, Batislam E, Basar MM, et al. The comparison and efficacy of 3 different alpha1-adrenergic blockers for distal ureteral stones. J Urol. 2005;173:2010–2012. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000158453.60029.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porpiglia F, Ghignone G, Fiori C, et al. Nifedipine versus tamsulosin for the management of lower ureteral stones. J Urol. 2004;172:568–571. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000132390.61756.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dellabella M, Milanese G, Muzzonigro G. Randomized trial of the efficacy of tamsulosin, nifedipine and phloroglucinol in medical expulsive therapy for distal ureteral calculi. J Urol. 2005;174:167–172. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000161600.54732.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kupeli B, Irkilata L, Gurocak S, et al. Does tamsulosin enhance lower ureteral stone clearance with or without shock wave lithotripsy? Urology. 2004;65:1111–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gravina GL, Costa AM, Ronchi P, et al. Tamsulosin treatment increases clinical success rate of single extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy of renal stones. Urology. 2005;66:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lingeman JE, Lifshitz DA, Evan AP. Surgical management of urinary lithiasis. In: Walsh PC, Retik, Vaughan ED , Jr, Wein AJ., editors. Campbell’s Urology. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002. pp. 3432–3433. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Resim S, Ekerbicer HC, Ciftci A. Role of tamsulosin in treatment of patients with steinstrasse developing after extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. Urology. 2005;66:945–948. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deliveliotis C, Chrisofos M, Gougousis E, et al. Is there a role for alpha1-blockers in treating double-J stent-related symptoms? Urology. 2006;67:35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]