The Soret effect, also known as thermodiffusion, is a classic example of coupled transport (1) in which directed motion of a particle or macromolecule is driven by flow of heat down a thermal gradient. Generally, a particle moves from hot to cold, but the reverse is also seen under some conditions. Although it has been known for >150 years, the microscopic explanation of the Soret effect has remained unclear. In a recent issue of PNAS, Duhr and Braun (2) shed important light on the molecular mechanisms of the Soret effect by using a technique of single-particle tracking, which allows very sensitive measurements of how thermo-diffusion can be influenced by changes in the environment, as well as how the effect scales with parameters such as particle size and surface charge. Although there are numerous examples (3, 4) of exciting possibilities for technological uses of thermodiffusion, the importance of understanding the mechanism of the Soret effect goes beyond the practical applications. Ultimately, similar coupled processes in which a chemical reaction drives directed motion of a protein may lie at the heart of the mechanism of the biological motors and pumps essential for life. Detailed understanding of a variety of coupled transport processes, including the Soret effect, may lead to important advances in our ability to influence biological molecules and to use the insight gained from natural systems to help design synthetic nanoscale machines.

The Soret effect can be characterized in terms of two parameters: the thermal diffusion coefficient DT, defined by the assumed linear relationship between the velocity and the thermal gradient v = −DT∇T, and the Soret coefficient, ST = DT/D, which is the ratio between DT and the scalar diffusion coefficient D. To unravel the molecular mechanism for thermodiffusion, it is essential to understand how the parameters DT and ST depend on the properties of the solvent and solute (or colloidal particles) and to determine the general mechanisms by which particles move along a thermal gradient.

There are two generic classes of mechanisms by which thermodiffusion can occur: one based on fluid dynamics and the other based on thermodynamics. In the class based on hydrodynamics (5), the temperature gradient leads directly to some imbalance over the surface of the molecule that results in a net mechanical force F that drives the particle motion. A similar mechanism, although not involving a thermal gradient, has been proposed as a description of a self-propelled molecular motor driven by a chemical reaction catalyzed by the motor that creates an osmotic gradient that pushes the motor along (6). In the second type of mechanism, the local thermodynamic environment of the particle is effectively isotropic (7). The chemical potential of the particle depends on temperature and hence on space, but gently, in comparison with the radius of the particle itself. The particle moves preferentially to the colder regions, in which it is thermodynamically more stable, by random diffusion that is biased by the increasing stabilization in the colder regions, similar to a Brownian motor mechanism for molecular motors (8). The relative importance of these two types of mechanisms for a given particle of radius a depends on the ratio of the time to diffusively explore a region as large as itself, Δtdiff ∼ a2/D, vs. the time to move the same distance by deterministic thermodiffusion, ΔtT ∼ a/v = a/DT∇T. These two times are approximately equal when ∇T = (aST)−1, so for aST∇T > 1, we expect the motion to be governed by the deterministic component of the velocity and the mechanical force mechanism to be operative, whereas for aST∇T < 1, the particle has time to diffusively explore its environment, and the second, Brownian-type mechanism is probably operative. The experiments of Duhr and Braun (2) were carried out in the diffusive regime, where the particle is always in local equilibrium. Their results are consistent with a mechanism in which the dominant factor governing the Soret coefficient is the temperature dependence of the entropy change associated with hydration and with ionic shielding, resulting in the expression

where A is the surface area of the particle, shyd is the specific entropy of hydration, σeff is the effective surface charge density, and λDH is the Debye length. The coefficient β captures the effect of the temperature dependence of the Debye length and the dielectric coefficient. Under most conditions, the ionic shielding term dominates and the Soret coefficient is positive, but the charge density and Debye length can be manipulated by changing the temperature and the ionic environment to suppress this shielding term, leading to a negative Soret coefficient: particles move toward warmer regions. Brenner (9), based on an entirely different perspective, suggested that DT is proportional to the thermal expansion coefficient. This model predicts that in water, the sign reversal of ST should occur near 4°. It does so for DNA but not for colloidal particles in the experiments of Duhr and Braun (2). The results are also consistent with the theoretical prediction based on the equality between the Soret coefficient and the negative solvation entropy divided by thermal noise that ST should be proportional to the surface area of the particles over a wide range of particle sizes. This size dependence is in strong contrast to previous theoretical models based on hydrodynamics (5, 10, 11) that suggest that DT should be independent of the particle size, and hence ST should be proportional to the radius. Thermodiffusion is patently a thermodynamically nonequilibrium effect, driven by the energetically downhill flow of heat from hot to cold. It thus is surprising that the relative concentration of particles at two arbitrary positions αi and αj obeys an equilibrium-like exponential relationship at steady state over a very wide range of conditions (7) css(αj)/css(αi) = exp{−ST[T((αj) − T(αi)]}. This equilibrium-like behavior perhaps can be understood in the context of a generalized fluctuation dissipation theorem (12),

that states that even under strongly thermodynamically nonequilibrium conditions, the ratio of the probability of a transition to the probability of the reverse of that transition is the exponent of the change in the internal energy of the system due to the transition. In Eq. 2, α is a generalized position (and hence α̇ is a generalized velocity), X is a generalized force, P[X, α̇] is the probability density for a trajectory or sequence of values α̇ and X, and the change in internal energy of the system ΔE = ∫ Xα̇dt = ∫ Xdα is the integral of the generalized force times generalized displacement. The striking relation 〈exp(−ΔE/kBT)〉 = 1 for the change in internal energy averaged over many trajectories follows immediately from Eq. 2 (12).

For overdamped systems such as those studied by Duhr and Braun (2), the generalized fluctuation–dissipation relation can be easily derived by using a Langevin equation for particle motion (13),

where the temperature is an explicit function of position and R is the coefficient of viscous friction. Diffusion is viewed as thermally activated hopping on a corrugated (but macroscopically flat) energy landscape U(α). We can eliminate the position dependence of the coefficient of the noise by multiplying both sides of the equation with , where T0 is an arbitrary reference temperature; i.e., we make the transformation {T, U, α} → {κT, κU, α} (14). The resulting equation describes simple equilibrium isothermal Brownian motion on a rescaled energy surface. The effects of the energy dissipation (thermodynamic disequilibrium) show up only in the transformation that maps the system onto the new coordinates. Because ξ(t) can be well modeled as Gaussian noise [arising from the ≈1021 collisions between the particle or DNA molecule with water molecules each second (15)], the probability for a given sequence of Brownian kicks in a time interval Δt is (16)

|

The argument of the second exponent is the thermodynamic action proposed by Onsager and Machlup (16) in their least-dissipation theory for stochastic processes.

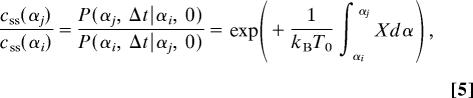

For every trajectory that takes a particle from the arbitrary position αi at t = 0 to αj at t = Δt, there is a reverse trajectory with opposite sign velocity at every instant that takes a particle from αj at t = 0 to αi at t = Δt. Consequently, by dividing the second integral in the above equation by itself but with the sign of α̇ reversed, we obtain the much simpler generalized fluctuation–dissipation relation (12),

|

where X = −κU′ is the rescaled local force acting on the particle. We used the steady-state condition css(αi) P(αj, Δt|αi, 0) = css(αj)P(αi, Δt|αj, 0), where P(αj, Δt|αi, 0) is the conditional probability density that a particle is at αj at Δt, given that it started at αi at t = 0. For a simple potential [e.g., U(α)= α4−α2 as treated in Landauer's blowtorch model (17) for thermally induced directed transport] and for small linear thermal gradient, the integral is an approximately linear function of ΔT. The equation is valid, however, even when the integral is a strongly nonlinear function of ΔT.

There is some confusion of the use of the term “linear” in the literature. Clearly, the Onsager/Machlup theory, based on the relation α̇ = X, is a linear theory and requires “that the fluxes depend linearly on the forces that ‘cause' them” (16). Because of strong viscous damping and very rapid velocity relaxation, this condition is met for the mechanical motion of almost any micro- or nanoscale system in water, even when under the influence of strong external forces or large thermal gradients. Indeed, it is almost impossible to imagine an experimentally attainable thermal gradient where this would not be the case for a particle in solution. A second use of the term linear appears in the context of Linear Response Theory, which focuses on the response of a system to some external perturbation. It is relatively easy to apply thermal gradients large enough that the net effective force and hence the velocity are not a linear function of the thermal gradient. Even so, the generalized fluctuation–dissipation relation holds (12).

In general, for particles smaller than a few micrometers in solution, the viscous drag force is equal to and opposite the mechanical and thermodiffusive forces, and there is no acceleration (18). This force balance holds even if the source-driving motion is far from equilibrium with the bath in which the particle moves. Thus, the particle is itself in mechanical equilibrium (13) and undergoes equilibrium fluctuations, as described in a suitable coordinate system. The particle simply serves as a “conduit” for energy to flow from the source of the mechanical force or thermal gradient to the bath. A molecular motor can be viewed as a molecule or nanoscale device that couples two external sources to a heat bath in such a way that the flow of energy from the stronger source can rectify the occasional reversal of the flow of energy between the bath and the weaker source, allowing energy to be pumped from the bath to do work on the weaker source. The energy for the reversal is provided by the stronger source, but the mechanism takes advantage of the omnipresent fluctuations in the energy flows due to thermal or other sources of noise. These fluctuation-driven molecular motors (19) share far more in common with the coupled transport processes (1) discussed by Duhr and Braun (2) than they do with the macroscopic motors and pumps. It seems likely that further investigation to resolve the many remaining questions concerning the molecular mechanism of the Soret effect will lead to further insight into a general understanding of coupled transport processes, with far-reaching consequences in many fields.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 19678. in issue 52 of volume 103.

References

- 1.Onsager L. Phys Rev. 1931;37:405–426. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duhr S, Braun D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19678–19682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603873103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braun D, Libchaber A. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;89:188103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.188103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang M, Muller-Plathe F. J Chem Phys. 2006;125:124903. doi: 10.1063/1.2356469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parola A, Piazza R. Eur Phys J E. 2004;15:255–263. doi: 10.1140/epje/i2004-10065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golestanian R, Liverpool TB, Ajdari A. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;94:220801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.220801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duhr S, Braun D. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;96:168301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.168301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Astumian RD, Hanggi P. Phys Today. 2002;55:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenner H. Phys Rev E. 2006;74:036306. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.74.036306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morozov KI. J Exp Theor Phys. 1999;88:944–946. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bielenberg JR, Brenner H. Physica A. 2005;356:279–293. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bochkov GN, Kuzovlev YE. Physica A. 1981;106:443–479. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Astumian RD. Am J Phys. 2006;74:683–688. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Derenyi I, Astumian RD. Phys Rev E. 1999;59:R6219–R6222. doi: 10.1103/physreve.59.r6219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandrasekhar S. Rev Mod Phys. 1949;21:383–388. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Onsager L, Machlup S. Phys Rev. 1953;91:1505–1512. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landauer R. J Stat Phys. 1988;53:233–248. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Purcell E. Am J Phys. 1977;45:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reimann P. Phys Rep. 2002;361:57–265. [Google Scholar]