Abstract

Extramedullary haematopoiesis (EMH) is a reactive mechanism by which blood cells are produced outside of the bone marrow to supplement insufficient production or increased destruction of erythrocytes. EMH is uncommon in sickle cell anaemia (SCA). We report the first case of focal intra-hepatic EMH in SCA depicted on MRI occurring in a 32-year-old woman with homozygote SCA and in view of previously published data, highlight the diagnostic features suggesting a differential diagnosis with other focal liver lesions including infectious, inflammatory or primary liver tumors.

Keywords: Liver, extramedullary haematopoiesis, sickle cell anaemia, MRI

Introduction

Extramedullary haematopoiesis (EMH) is a reactive mechanism by which blood cells are produced outside of the bone marrow to supplement insufficient production or increased destruction of erythrocytes. EMH is observed in marrow depletion or infiltration such as lymphoma, leukaemia [1] or with marrow hyperactivity in conditions such as congenital haemolytic anaemia (thalassaemia and hereditary spherocytosis) [2]. Common sites of EMH include the mediastinum, spleen, and lymph nodes [2, 3]. Very little is known about the MR appearance of intra-hepatic EMH. Iron overload is frequent in congenital haemolytic anaemias and is usually related to chronic transfusion [4]. Although unusual, focal intra-hepatic EMH in this setting can mimic other solid lesions of the liver leading to a troublesome differential diagnosis with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [5, 6]. To our knowledge the specific MR features of intra-hepatic EMH have been reported in just four separated case reports [1, 5, 7, 8]. EMH is however uncommon in sickle cell anaemia (SCA) [5]. We report the first case of focal intra-hepatic EMH in SCA depicted on MRI and in view of previously published data, highlight the diagnostic features suggesting a differential diagnosis with HCC.

Case report

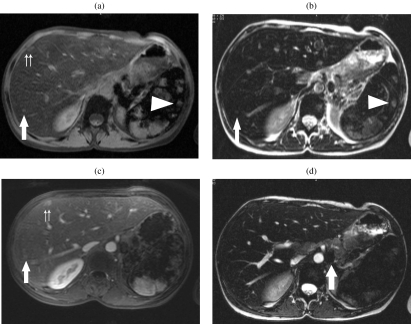

L.F., a 32-year-old woman with homozygote sickle cell disease and a 15-year history of transfusion was referred to our institution in May 1998 with elevated ferritine levels suggesting haemosiderosis. Her past medical history included respiratory infections and cholecystectomy. Biochemical liver tests were normal apart from a two-fold increase in bilirubin levels. Fetoprotein level was normal and hepatitis C serology was positive for chronic infection. Ultrasound examination of the upper abdomen showed a liver size within normal limits without any detectable focal lesions. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the liver was performed for assessment of iron overload. The liver and spleen showed a diffuse low signal intensity compared to that of muscle on all MR imaging sequences (Siemens ® Symphony 1.5 T; Erlangen, Germany) with multiple nodular lesions that were hyperintense to the liver and isointense to the muscle on gradient echo (GE) T1 weighted images (WI) (TR = 178; TE = 3; slice thickness = 7 mm; α=70) with or without selective fat saturation (Fig. 1(a)) and on 3D GE T1 WI (VIBE, volume interpolated breathheld examination; Siemens ®; Erlangen, Germany) (TR = 4; TE = 1.5; slice thickness = 3 mm; α=20) (Fig. 1(a)) and slightly hyperintense to the liver and isointense to the muscle on fast spin echo (TSE) T2 WI (TR = 384; TE = 92; slice thickness = 7 mm) (Fig. 1(b)). These lesions showed absent enhancement on arterial phase and moderate enhancement on the later phases following the injection of 0.1 mmol /kg of Gd-DOTA (Dotarem ®, Guerbert, Aulnay, France) (Fig. 1(c)). Multiple para-aortic nodes showing low signal intensity on T2 WI (Fig. 1(d)) were simultaneously demonstrated. A triple phase computed tomography (CT) scan (5 mm collimation; CT Twin ® Elscint ®; Haifa, Israel) of the liver showed multiple nodular lesions isodense to the liver prior to injection, with absent enhancement on arterial phase and homogeneous enhancement on portal phase imaging following the injection of 90 cm 3 of Iohexol (Omnipaque300 ®; Guerbert, Aulnay, France). The largest lesion located in segment V was 1.5 cm in diameter. CT guided liver biopsy within the lesion showed periportal fibrosis and sinusoid dilatation with megakaryocytes suggesting EMH. MRI control performed 5 years later (not shown) showed similar findings, without any increase in the size of the previously identified liver lesions.

Figure 1.

A 32-year-old woman with homozygote sickle cell disease and a 15-year history of transfusion. The liver shows diffuse low signal intensity on all sequences. (a) Fat saturation GRE images show the presence of multiple nodules hyperintense within the liver and remaining isointense to the muscle (arrow and double arrows). Nodules displaying a similar pattern of signal intensity are identified in the spleen (arrowhead). (b) T2 WI TSE fat saturation images show that the multiple nodes are slightly hyperintense to the adjacent liver, and isointense to the muscle (arrow). (c) Following injection of Gd-DOTA (Dotarem ®, Guerbet, Aulnay, France), previously identified nodes show absent enhancement on arterial phase and moderate enhancement on portal phase imaging (arrow and double arrows). Nodules displaying a similar pattern of signal intensity are identified in the spleen (arrowhead). (d) Multiple para-aortic nodes showing low intensity on TSE T2 WI (arrow) consistent with iron accumulation were discovered incidentally.

Discussion

SCA is a haemolytic anaemia characterised by the presence of abnormally shaped erythrocytes, which are destroyed at increased rates, leading to chronic anaemia [3]. In order to sustain the needs of the organism demands, extramedullary production of erythrocytes can be stimulated. Common sites of EMH include the mediastinum, spleen, and lymph nodes [2, 3]. In the liver, both diffuse microscopic infiltration or focal mass-like lesions have been reported with EMH [2, 9, 10]. Focal nodular intra-hepatic EMH is a rare disorder presenting as well defined, regular shaped focal liver lesions on all imaging modalities [1]. The ultrasound (US) appearance of focal intra-hepatic EMH is however non-specific. Both hypo-echoic, or hyper-echoic generally inhomogeneous nodules have been associated with intra-hepatic EMH [2]. On CT, intra-hepatic EMH lesions are usually hypodense to the liver, frequently hetereogeneous, and can show patchy or no enhancement following contrast injection [2, 11]. Intra-hepatic EMH are generally multiple, but solitary lesions have been reported [9, 12]. Therefore, the number of lesions cannot help in the differential diagnosis. The presence of extra-hepatic EMH can on the other hand provide additional clues. In ten previously reported cases of intra-hepatic EMH, extra-hepatic EMH were present in five cases, absent in two and not evaluated in three cases [1]. The MR features of intra-hepatic EMH have been rarely reported and never in SCA. In addition to our case we reviewed the four previously published literature cases. The results are summarized in Table 1. The baseline signal intensity of intra-hepatic EMH relative to the adjacent liver varies between case reports: (1) according to Elsayes et al., the signal intensity of the mass is primarily related to the presence of active or inactive haematopoiesis. Active lesions show intermediate signal intensity on T1 WI, mild high signal intensity on T2 WI, and some enhancement after intravenous contrast medium injection. Older lesions may show low signal intensity on T1 and T2 WI and may not show any enhancement [10]. (2) In our report, intra-hepatic EMH were isointense to the muscle but hyperintense to the liver on T1 WI because of hepatic iron overload. This confirms that the relative signal intensity of focal intra-hepatic EMH to adjacent liver on MR is influenced by the degree of iron deposits in the liver. Haemosiderosis of the liver is indeed a common finding in patients with chronic haematological impairment requiring repeated transfusions [4] and was present in our case.

Table 1.

Focal intra-hepatic extra-medullary haematopoiesis: review of the literature

| T1 WI | T2 WI | Gd-DTPA | Other location | Underlying | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| condition | |||||

| Warshauer 1991 [1] | Isointense to L and M | Hyper intense to L and M | Heterogeneous | No | Unknown |

| enhancement | |||||

| Kumar 1995 [1] | Hypointense to M, | Hypointense to M, | Not evaluated | Para-vertebral | β-Thalassaemia |

| isointense to L | isointense to L | ||||

| Tamm 1995 [1] | Hypointense to L | Hyperintense to L | No enhancement on | No | Gaucher disease |

| dynamic injection, | |||||

| delayed enhancement | |||||

| Wong 1999 [1] | Hyperintense to L, | Hyperintense to L, | Hetereogeneous | No | β-Thalassaemia |

| isointense to M | isointense to M | enhancement | |||

| Jelali 2006 | Hyperintense to L, | Slightly hyperintense to L, | Absent in arterial phase | Para-aortic and | Sickle cell disease |

| (this paper) | isointense to M | isointense to M | and moderate in later phases | para-spinal | |

L, liver; M, muscle.

It has been demonstrated that liver iron overload leads to progressive fibrosis, which in turn can lead to cirrhosis. The increased risk of HCC in cirrhotic liver is well documented [13]. However, our study suggests that the presence of isointense or very mild hyperintense lesions on T2 WI in patients at risk for EMH is less suggestive of HCC, especially in liver with iron overload [14]. Furthermore, although non-specific, the isointensity or mild hyperintensity of intra-hepatic EMH nodules on T2 WI which we report on MR are not suggestive of cavernous haemangioma [15]. The differential diagnosis of multiple splenic and hepatic lesions such as those we present should also include sarcoidosis and atypical infection. Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous systemic disease of unknown aetiology that can involve numerous sites. Nodular sarcoidosis has been reported to demonstrate low signal intensity on all MR imaging sequences. The lesions are most conspicuous on T2-weighted fat-suppressed or early phase contrast-enhanced images. Sarcoidosis lesions enhance in a minimal and delayed pattern [10, 14]. Candidiasis is the most common infection involving the liver and spleen in immunocompromised patients. The lesions appear as multiple hypointense, ring-enhancing lesions less than 1 cm in diameter on gadolinium-enhanced images [10, 14]. Although seen in patients with competent immune systems, the prevalence of histoplasmosis is greater in immunocompromised patients. MR imaging demonstrates the acute and subacute phases of this disease as scattered hypointense lesions on both T1 and T2 WI, with no significant enhancement following contrast material administration. Old granulomas can be calcified [10, 14]. Thus, clinical, biological and imaging data did not favour sarcoidosis or atypical infections in our patient.

Based on our case and in review of the literature data, we believe that the most distinctive feature of intra-hepatic EMH is progressive and delayed enhancement after Gd-chelates injection. Delayed enhancement following contrast injection was present in our case and was also reported in all but one previously published case where no mention of contrast injection was provided. We believe that this feature could help to differentiate intra-hepatic EMH from HCC in patients with haemolytic anaemia as arterial enhancement of larger than 10 mm nodules in cirrhotic liver is in favour of HCC [16]. Wong reported the first description of stellate scars occurring within intra-hepatic EMH showing low signal intensity on T1 WI, high signal intensity on T2 WI and delayed enhancement [1]. More recently, focal intrahepatic extramedullary haematopoiesis has been reported to contain fat [12]. We did not encounter these patterns in our report. The performance of liver MR was not compared in our case with that of scintigraphic studies. The sensitivity of 99Tcm scintigraphy in detecting intra-hepatic EMH is poor [1]. However, 52Fe imaging could be helpful in confirming the diagnosis [1]. Our study suggests that when in doubt, the diagnosis of intra-hepatic EMH can be confirmed by CT or US guided biopsy [17].

Conclusion

With the increasing use of MR in the evaluation of hepatic masses, EMH should be remembered as a rare cause of focal liver lesion, especially in patients presenting disturbed medullary haematopoiesis, often accompanying congenital haemoglobinopathies. Most intra-hepatic EMH lesions appear as well defined nodules. The presence of isointense or only slightly hyperintense liver nodules on T2 WI, with delayed, enhancement after dynamic contrast injection, possibly associated with other locations of EMH are suggestive of intra-hepatic EMH. Although some of these imaging features may overlap those of focal infections or inflammatory lesions, these findings could help in excluding the diagnosis of primary liver tumors in such patients.

References

- 1.Wong Y, Chen F, Tai KS, et al. Imaging features of focal intrahepatic extramedullary haematopoiesis. Br J Radiol. 1999;72:906–10. doi: 10.1259/bjr.72.861.10645201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navarro M, Crespo C, Perez L, Martinez C, Galant J, Gonzalez I. Massive intrahepatic extramedullary hematopoiesis in myelofibrosis. Abdom Imaging. 2000;25:184–6. doi: 10.1007/s002619910041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lonergan GJ, Cline DB, Abbondanzo SL. Sickle cell anemia. Radiographics. 2001;21:971–94. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.4.g01jl23971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kushner JP, Porter JP, Olivieri NF. Secondary iron overload. Hematology (Am Soc Hematol Educ Program) 2001:47–61. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2001.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar A, Aggarwal S, de Tilly LN. Case of the season. Thalassemia major with extramedullary hematopoiesis in the liver. Semin Roentgenol. 1995;30:99–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aytac S, Fitoz S, Akyar S, Atasoy C, Erekul S. Focal intrahepatic extramedullary hematopoiesis: color Doppler US and CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 1999;24:366–8. doi: 10.1007/s002619900515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warshauer DM, Schiebler ML. Intrahepatic extramedullary hematopoiesis: MR, CT, and sonographic appearance. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1991;15:683–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tamm EP, Rabushka LS, Fishman EK, Hruban RH, Diehl AM, Klein A. Intrahepatic, extramedullary hematopoiesis mimicking hemangioma on technetium-99m red blood cell SPECT examination. Clin Imaging. 1995;19:88–91. doi: 10.1016/0899-7071(94)00037-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dewar G, Leung NW, Ng HK, Bradley M, Li AK. Massive, solitary, intrahepatic, extramedullary hematopoietic tumor in thalassemia. Surgery. 1990;107:704–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elsayes KM, Narra VR, Mukundan G, Lewis Jr JS, Menias CO, Heiken JP. MR imaging of the spleen: spectrum of abnormalities. Radiographics. 2005;25:967–82. doi: 10.1148/rg.254045154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwak HS, Lee JM. CT findings of extramedullary hematopoiesis in the thorax, liver and kidneys, in a patient with idiopathic myelofibrosis. J Korean Med Sci. 2000;15:460–2. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2000.15.4.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta P, Naran A, Auh YH, Chung JS. Focal intrahepatic extramedullary hematopoiesis presenting as fatty lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:1031–2. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.4.1821031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hwang YH, Choi JY, Kim S, et al. Over-expression of c-raf-1 proto-oncogene in liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2004;29:113–21. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elsayes KM, Narra VR, Yin Y, Mukundan G, Lammle M, Brown JJ. Focal hepatic lesions: diagnostic value of enhancement pattern approach with contrast-enhanced 3D gradient-echo MR imaging. Radiographics. 2005;25:1299–320. doi: 10.1148/rg.255045180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vilgrain V, Boulos L, Vullierme MP, Denys A, Terris B, Menu Y. Imaging of atypical hemangiomas of the liver with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2000;20:379–97. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.2.g00mc01379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krinsky GA, Nguyen MT, Lee VS, et al. Dysplastic nodules and hepatocellular carcinoma: sensitivity of digital subtraction hepatic arteriography with whole liver explant correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24:628–34. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200007000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dardi LE, Marzano M, Froula E. Fine needle aspiration cytologic diagnosis of focal intrahepatic extramedullary hematopoiesis. Acta Cytol. 1990;34:567–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]