Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (239.8 KB).

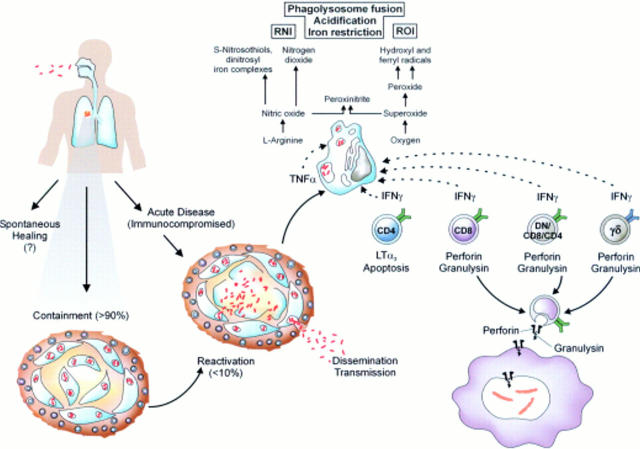

Figure 1 .

Different outcomes of infection with M tuberculosis, different T cell populations involved in protection, and major anti-mycobacterial effector mechanisms of macrophages. This scheme firstly depicts the different outcomes of tuberculosis in healthy and immunocompromised subjects. Secondly, the figure shows the different T cell populations and their major T cell effector mechanisms in the control of disease. Thirdly, the figure shows anti-mycobacterial effector mechanisms of activated macrophages. (Reproduced from Nature Reviews Immunology (vol 1:20–30). Reprinted by permission from Nature Reviews Immunology (2001;1:20–30). Copyright © 2001 Macmillan Magazines Ltd.)

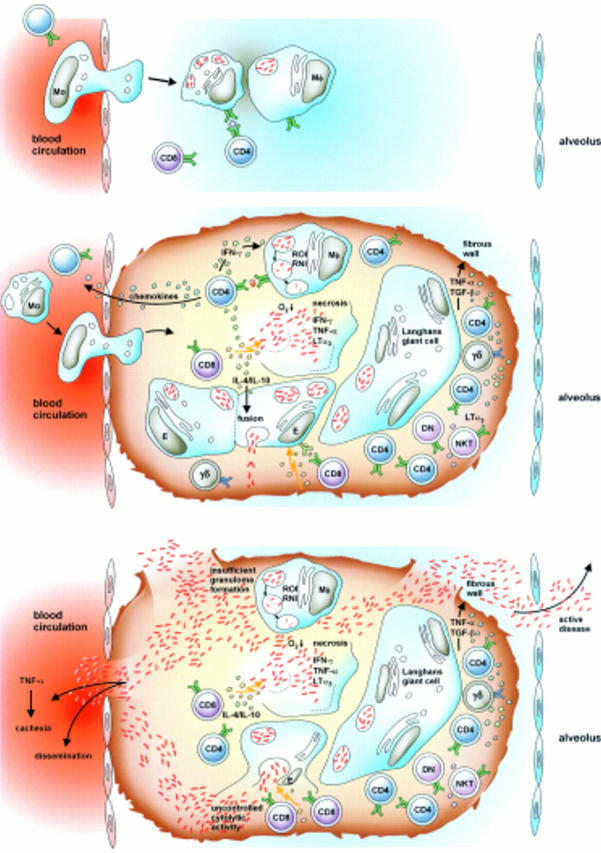

Figure 2 .

Development of granulomatous lesions in tuberculosis. Promptly after infection, T cells and macrophages are attracted to the site of mycobacterial implantation. There, granulomatous lesions develop. As long as the immune response is competent, the lesions will contain bacteria. These productive granulomas represent a focus of highly dynamic interactions between different T cell populations, macrophages of different maturation stages, and dendritic cells. Once immunity weakens, the balance is tipped and the granuloma can no longer contain mycobacteria. Rather, the granulomatous lesion liquefies and bacteria are released to different tissue sites, different organs, and to the environment. Active disease develops and the patient becomes contagious. (For further details see ref 8.)

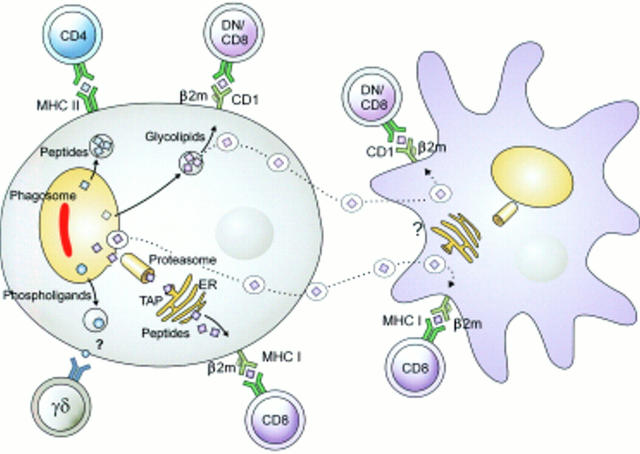

Figure 3 .

Different antigen presentation pathways in tuberculosis. Mycobacterial antigens reside in the early phagosome. There, their proteins have ready access to MHC class II processing, resulting in potent CD4 T cell stimulation. Phospholigands are produced by these mycobacteria, which stimulate γδ T cells in the absence of known antigen presentation molecules. Presentation of proteins by MHC class I and of glycolipids by CD1 is more complex and probably requires cross priming. Mycobacteria infected macrophages undergo apoptosis. Resulting extracellular vesicles carry antigens to bystander dendritic cells. Uptake of these vesicles results in glycolipid presentation through CD1 and protein presentation through MHC class I. This two cell mechanism can explain stimulation of MHC class I restricted CD8 T cells and of CD1 restricted T cells. (Reproduced from Nature Reviews Immunology (vol 1:20–30). Reprinted by permission from Nature Reviews Immunology (2001;1:20–30). Copyright © 2001 Macmillan Magazines Ltd.)

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Flesch I. E., Kaufmann S. H. Role of cytokines in tuberculosis. Immunobiology. 1993 Nov;189(3-4):316–339. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80364-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn J. L., Goldstein M. M., Chan J., Triebold K. J., Pfeffer K., Lowenstein C. J., Schreiber R., Mak T. W., Bloom B. R. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is required in the protective immune response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Immunity. 1995 Jun;2(6):561–572. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann S. H. How can immunology contribute to the control of tuberculosis? Nat Rev Immunol. 2001 Oct;1(1):20–30. doi: 10.1038/35095558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann S. H. Is the development of a new tuberculosis vaccine possible? Nat Med. 2000 Sep;6(9):955–960. doi: 10.1038/79631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maini R., St Clair E. W., Breedveld F., Furst D., Kalden J., Weisman M., Smolen J., Emery P., Harriman G., Feldmann M. Infliximab (chimeric anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody) versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving concomitant methotrexate: a randomised phase III trial. ATTRACT Study Group. Lancet. 1999 Dec 4;354(9194):1932–1939. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)05246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan V. P., Scanga C. A., Yu K., Scott H. M., Tanaka K. E., Tsang E., Tsai M. M., Flynn J. L., Chan J. Effects of tumor necrosis factor alpha on host immune response in chronic persistent tuberculosis: possible role for limiting pathology. Infect Immun. 2001 Mar;69(3):1847–1855. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1847-1855.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach D. R., Briscoe H., Saunders B., France M. P., Riminton S., Britton W. J. Secreted lymphotoxin-alpha is essential for the control of an intracellular bacterial infection. J Exp Med. 2001 Jan 15;193(2):239–246. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.2.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]