Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (183.4 KB).

Figure 1 .

The complement cascade. *Indicates known biologically active complement fragments with the potential to influence the pathophysiology of disease.

Figure 2 .

Inhibiton of C3 convertase ameliorates aPL-IgG induced pregnancy complications. Female BALB/c mice were treated ip with IgG (10 mg) from a patient with APS (aPL), normal human IgG (Cntrl IgG) or saline (Vehicle) on days 8 and 12 of pregnancy. Some of the mice received an inhibitor of C3 convertase, Crry-Ig (3 mg ip) every other day from days 8–12. Mice were killed on day 15 of pregnancy, uteri were dissected, fetuses were weighed, and frequency of fetal resorption calculated (number of resorptions/number of fetuses + number of resorptions). There were six mice in each group. (A) Treatment with aPL-IgG caused an increase in fetal resorptions compared with vehicle or control human IgG (*p<0.05), which was prevented by Crry-Ig (*aPL v aPL + Crry-Ig p<0.05). (B) aPL-IgG caused fetal growth retardation (*aPL v Cntrl IgG p<0.01), which was also prevented by Crry-Ig (*aPL v aPL + Crry-Ig p<0.01). Reproduced from the J Exp Med 2001;195:214 by copyright permission of The Rockefeller Press.

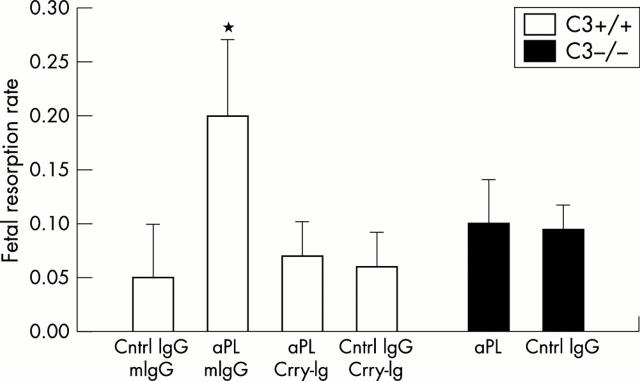

Figure 3 .

C3 deficient mice are protected from aPL antibody induced pregnancy complications. C3+/+ mice (B6/Sv129F1) were treated with aPL-IgG (10 mg ip) (aPL) or normal human IgG (Cntrl IgG) on days 8 and 12 of pregnancy. Half of the mice in each group received Crry-Ig (3 mg ip) every other day from days 8–12 and half received control murine IgG (mIgG). C3-/- mice were treated with either aPL-IgG or normal human IgG. Pregnancy outcomes were assessed as described in the legend for fig 2. There were 10–14 mice in each experimental group. (A) Analysis of the four groups of C3+/+ mice shows that treatment with aPL-IgG caused an increase in frequency of fetal resorptions in this strain (*aPL + mIgG v Cntrl IgG + mIgG p<0.01), while C3-/- were protected from aPL induced pregnancy loss (aPL v Cntrl IgG p=NS). In the C3+/+ mice, Crry-Ig prevented aPL induced fetal resorption (*aPL + mIgG v aPL + Crry-Ig p<0.01). (B) Similarly, aPL treatment caused a decrease in fetal weight in C3+/+ mice (*aPL + mIgG v Cntrl IgG + mIgG p<0.01), which was absent in C3-/- mice, and this was ameliorated by Crry-Ig (*aPL + mIgG v aPL + Crry-Ig p<0.01). Reproduced from the J Exp Med 2001;195:216 by copyright permission of The Rockefeller Press.

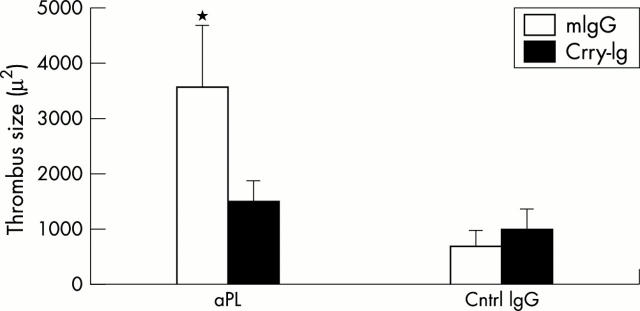

Figure 4 .

C3 activation is required for aPL induced thrombophilia. (A) aPL-IgG induced thrombophilia is inhibited by Crry-Ig. CD-1 mice were injected ip with affinity purified aPL-IgG (aPL) or normal human (Cntrl IgG) at 0 hours and 48 hours. Half the mice in each group received Crry-Ig, and half the mice received control murine IgG (mIgG). At 72 hours after the first injection, surgically induced thrombus formation was measured as described in the text. There were 11–14 mice in each experimental group. Treatment with aPL-IgG caused an increase in thrombus size (*aPL + mIgG v Cntrl IgG + mIgG p<0.05), while Crry-Ig prevented aPL induced enhancement of thrombosis (*aPL + mIgG v aPL + Crry-Ig p<0.05; Cntrl IgG + Crry-Ig v aPL + Crry-Ig, p=NS). In a separate series of experiments, aPL did not significantly increase thrombosis in C3-/- mice (aPL v control IgG 1524 (825) µm v 1083 (443), p=NS). There was no difference in the levels of human aPL activity between C3+/+ mice and C3-/- mice. Reproduced from the J Exp Med 2001;195:217 by copyright permission of The Rockefeller Press.

Figure 5 .

Proposed mechanism for the pathogenic effects of aPL antibodies on pregnancy outcome. aPL antibodies are preferentially targeted to the placenta where they may promote platelet and endothelial cell activation and directly induce procoagulant activity through interaction with elements of the coagulation pathway. This activity, however, does not seem to be sufficient to cause fetal loss or growth restriction; C3-/- are protected. Activation of the complement pathway by aPL-IgG overwhelms the normally adequate inhibitory mechanisms and amplifies these effects by stimulating the generation of further potent mediators of effector cell activation, including C3a, C5a, and the C5b-9 MAC. The addition of these complement activation products causes thrombosis, tissue hypoxia, and inflammation within the placenta, and ultimately leads to fetal injury.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Blank M., Cohen J., Toder V., Shoenfeld Y. Induction of anti-phospholipid syndrome in naive mice with mouse lupus monoclonal and human polyclonal anti-cardiolipin antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Apr 15;88(8):3069–3073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch D. W., Dudley D. J., Mitchell M. D., Creighton K. A., Abbott T. M., Hammond E. H., Daynes R. A. Immunoglobulin G fractions from patients with antiphospholipid antibodies cause fetal death in BALB/c mice: a model for autoimmune fetal loss. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Jul;163(1 Pt 1):210–216. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)90700-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch D. W., Silver R. M., Blackwell J. L., Reading J. C., Scott J. R. Outcome of treated pregnancies in women with antiphospholipid syndrome: an update of the Utah experience. Obstet Gynecol. 1992 Oct;80(4):614–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown E. J. Complement receptors and phagocytosis. Curr Opin Immunol. 1991 Feb;3(1):76–82. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(91)90081-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll M. C. The role of complement and complement receptors in induction and regulation of immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:545–568. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaouat G., Menu E., Clark D. A., Dy M., Minkowski M., Wegmann T. G. Control of fetal survival in CBA x DBA/2 mice by lymphokine therapy. J Reprod Fertil. 1990 Jul;89(2):447–458. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0890447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford K., Rai R., Watson H., Regan L. An informative protocol for the investigation of recurrent miscarriage: preliminary experience of 500 consecutive cases. Hum Reprod. 1994 Jul;9(7):1328–1332. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham D. S., Tichenor J. R., Jr Decay-accelerating factor protects human trophoblast from complement-mediated attack. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1995 Feb;74(2):156–161. doi: 10.1006/clin.1995.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daffern P. J., Pfeifer P. H., Ember J. A., Hugli T. E. C3a is a chemotaxin for human eosinophils but not for neutrophils. I. C3a stimulation of neutrophils is secondary to eosinophil activation. J Exp Med. 1995 Jun 1;181(6):2119–2127. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.6.2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Papa N., Guidali L., Sala A., Buccellati C., Khamashta M. A., Ichikawa K., Koike T., Balestrieri G., Tincani A., Hughes G. R. Endothelial cells as target for antiphospholipid antibodies. Human polyclonal and monoclonal anti-beta 2-glycoprotein I antibodies react in vitro with endothelial cells through adherent beta 2-glycoprotein I and induce endothelial activation. Arthritis Rheum. 1997 Mar;40(3):551–561. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Papa N., Raschi E., Moroni G., Panzeri P., Borghi M. O., Ponticelli C., Tincani A., Balestrieri G., Meroni P. L. Anti-endothelial cell IgG fractions from systemic lupus erythematosus patients bind to human endothelial cells and induce a pro-adhesive and a pro-inflammatory phenotype in vitro. Lupus. 1999;8(6):423–429. doi: 10.1177/096120339900800603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine D. V. The effects of complement activation on platelets. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1992;178:101–113. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-77014-2_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Simone N., Meroni P. L., de Papa N., Raschi E., Caliandro D., De Carolis C. S., Khamashta M. A., Atsumi T., Hughes G. R., Balestrieri G. Antiphospholipid antibodies affect trophoblast gonadotropin secretion and invasiveness by binding directly and through adhered beta2-glycoprotein I. Arthritis Rheum. 2000 Jan;43(1):140–150. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<140::AID-ANR18>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohoe S., Kingdom J. C., Mackie I. J. Affinity purified human antiphospholipid antibodies bind normal term placenta. Lupus. 1999;8(7):525–531. doi: 10.1191/096120399678840756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmon N. L., Safa O., Smirnov M. D., Esmon C. T. Antiphospholipid antibodies and the protein C pathway. J Autoimmun. 2000 Sep;15(2):221–225. doi: 10.1006/jaut.2000.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon D. T., Locksley R. M. The instructive role of innate immunity in the acquired immune response. Science. 1996 Apr 5;272(5258):50–53. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman K. E., Vaporciyan A. A., Bonish B. K., Jones M. L., Johnson K. J., Glovsky M. M., Eddy S. M., Ward P. A. C5a-induced expression of P-selectin in endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1994 Sep;94(3):1147–1155. doi: 10.1172/JCI117430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerard N. P., Gerard C. The chemotactic receptor for human C5a anaphylatoxin. Nature. 1991 Feb 14;349(6310):614–617. doi: 10.1038/349614a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holers V. Michael, Girardi Guillermina, Mo Lian, Guthridge Joel M., Molina Hector, Pierangeli Silvia S., Espinola Ricardo, Xiaowei Liu E., Mao Dailing, Vialpando Christopher G. Complement C3 activation is required for antiphospholipid antibody-induced fetal loss. J Exp Med. 2002 Jan 21;195(2):211–220. doi: 10.1084/jem.200116116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes C. H., Simpson K. L. Complement and pregnancy: new insights into the immunobiology of the fetomaternal relationship. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1992 Sep;6(3):439–460. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3552(05)80005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikematsu W., Luan F. L., La Rosa L., Beltrami B., Nicoletti F., Buyon J. P., Meroni P. L., Balestrieri G., Casali P. Human anticardiolipin monoclonal autoantibodies cause placental necrosis and fetal loss in BALB/c mice. Arthritis Rheum. 1998 Jun;41(6):1026–1039. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199806)41:6<1026::AID-ART9>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imrie H. J., McGonigle T. P., Liu D. T., Jones D. R. Reduction in erythrocyte complement receptor 1 (CR1, CD35) and decay accelerating factor (DAF, CD55) during normal pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol. 1996 Oct;31(3):221–227. doi: 10.1016/0165-0378(96)00977-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaleli B., Kaleli I., Aktan E., Turan C., Akşit F. Antiphospholipid antibodies in eclamptic women. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1998;45(2):81–84. doi: 10.1159/000009930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutteh W. H. Antiphospholipid antibody-associated recurrent pregnancy loss: treatment with heparin and low-dose aspirin is superior to low-dose aspirin alone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996 May;174(5):1584–1589. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70610-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine Jerrold S., Branch D. Ware, Rauch Joyce. The antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2002 Mar 7;346(10):752–763. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra002974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima F., Khamashta M. A., Buchanan N. M., Kerslake S., Hunt B. J., Hughes G. R. A study of sixty pregnancies in patients with the antiphospholipid syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1996 Mar-Apr;14(2):131–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liszewski M. K., Farries T. C., Lublin D. M., Rooney I. A., Atkinson J. P. Control of the complement system. Adv Immunol. 1996;61:201–283. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60868-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockshin M. D., Sammaritano L. R., Schwartzman S. Validation of the Sapporo criteria for antiphospholipid syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2000 Feb;43(2):440–443. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200002)43:2<440::AID-ANR26>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magid M. S., Kaplan C., Sammaritano L. R., Peterson M., Druzin M. L., Lockshin M. D. Placental pathology in systemic lupus erythematosus: a prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Jul;179(1):226–234. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70277-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan B. P., Meri S. Membrane proteins that protect against complement lysis. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1994;15(4):369–396. doi: 10.1007/BF01837366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Out H. J., Kooijman C. D., Bruinse H. W., Derksen R. H. Histopathological findings in placentae from patients with intra-uterine fetal death and anti-phospholipid antibodies. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1991 Oct 8;41(3):179–186. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(91)90021-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattison N. S., Chamley L. W., Birdsall M., Zanderigo A. M., Liddell H. S., McDougall J. Does aspirin have a role in improving pregnancy outcome for women with the antiphospholipid syndrome? A randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Oct;183(4):1008–1012. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierangeli S. S., Colden-Stanfield M., Liu X., Barker J. H., Anderson G. L., Harris E. N. Antiphospholipid antibodies from antiphospholipid syndrome patients activate endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo. Circulation. 1999 Apr 20;99(15):1997–2002. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.15.1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piona A., La Rosa L., Tincani A., Faden D., Magro G., Grasso S., Nicoletti F., Balestrieri G., Meroni P. L. Placental thrombosis and fetal loss after passive transfer of mouse lupus monoclonal or human polyclonal anti-cardiolipin antibodies in pregnant naive BALB/c mice. Scand J Immunol. 1995 May;41(5):427–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1995.tb03588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai R., Cohen H., Dave M., Regan L. Randomised controlled trial of aspirin and aspirin plus heparin in pregnant women with recurrent miscarriage associated with phospholipid antibodies (or antiphospholipid antibodies) BMJ. 1997 Jan 25;314(7076):253–257. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7076.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehrig S., Fleming S. D., Anderson J., Guthridge J. M., Rakstang J., McQueen C. E., Holers V. M., Tsokos G. C., Shea-Donohue T. Complement inhibitor, complement receptor 1-related gene/protein y-Ig attenuates intestinal damage after the onset of mesenteric ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. J Immunol. 2001 Nov 15;167(10):5921–5927. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt B. Z., Colten H. R. Complement: a critical test of its biological importance. Immunol Rev. 2000 Dec;178:166–176. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.17801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simantov R., LaSala J. M., Lo S. K., Gharavi A. E., Sammaritano L. R., Salmon J. E., Silverstein R. L. Activation of cultured vascular endothelial cells by antiphospholipid antibodies. J Clin Invest. 1995 Nov;96(5):2211–2219. doi: 10.1172/JCI118276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson M. D. Frequency of factors associated with habitual abortion in 197 couples. Fertil Steril. 1996 Jul;66(1):24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco F., Narchi G., Radillo O., Meri S., Ferrone S., Betterle C. Susceptibility of human trophoblast to killing by human complement and the role of the complement regulatory proteins. J Immunol. 1993 Aug 1;151(3):1562–1570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir P. E. Immunofluorescent studies of the uteroplacental arteries in normal pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1981 Mar;88(3):301–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1981.tb00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells M., Bennett J., Bulmer J. N., Jackson P., Holgate C. S. Complement component deposition in uteroplacental (spiral) arteries in normal human pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol. 1987 Oct;12(2):125–135. doi: 10.1016/0165-0378(87)90040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetsel R. A. Structure, function and cellular expression of complement anaphylatoxin receptors. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995 Feb;7(1):48–53. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetsel R. A. Structure, function and cellular expression of complement anaphylatoxin receptors. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995 Feb;7(1):48–53. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson W. A., Gharavi A. E., Koike T., Lockshin M. D., Branch D. W., Piette J. C., Brey R., Derksen R., Harris E. N., Hughes G. R. International consensus statement on preliminary classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome: report of an international workshop. Arthritis Rheum. 1999 Jul;42(7):1309–1311. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199907)42:7<1309::AID-ANR1>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C., Mao D., Holers V. M., Palanca B., Cheng A. M., Molina H. A critical role for murine complement regulator crry in fetomaternal tolerance. Science. 2000 Jan 21;287(5452):498–501. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5452.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yetman D. L., Kutteh W. H. Antiphospholipid antibody panels and recurrent pregnancy loss: prevalence of anticardiolipin antibodies compared with other antiphospholipid antibodies. Fertil Steril. 1996 Oct;66(4):540–546. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)58565-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]