Fresh leaves from khat trees (Catha edulis Celestrasae) are chewed daily by over 20 million people in Yemen and East African countries. Chewing khat (qat) is a popular social habit which has spread to Yemeni, Somali or East African communities in the USA and UK.1 The pleasure derived from khat chewing is attributed to the euphoric actions of S-(−)-cathinone, a sympathomimetic amine with properties similar to amphetamine.2 Although cathinone is restricted in the UK under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, khat possession and use are not.1 Cathinone increases blood pressure and heart rate through noradrenaline (norepinephrine) release from peripheral neurones similar to amphetamine.2 Controlled studies in human volunteers have shown increases in blood pressure after chewing khat coinciding with raised plasma cathinone concentrations.3 Cardiovascular complications from cathinone abuse may therefore be similar to those of amphetamine. We have noticed increasing numbers of patients presenting with acute heart attack in the evening either during or after a khat chewing session. This prospective study was therefore undertaken to examine whether khat chewing has a role in precipitating acute myocardial infarction.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

One hundred and fifty seven patients of Arabian origin admitted to the intensive care unit of Al-Thawra hospital, Sanaa, Yemen with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) between November 1995 and November 1997 underwent history taking, clinical examination, resting ECG monitoring, and determination of serum concentrations of total cholesterol, triglycerides and the cardiac enzymes, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and creatinine phosphokinase (CPK). Patients unable to provide the precise time of onset of symptoms were excluded. Patients were divided into khat chewers (79%) and non-chewers. Diagnosis of AMI was based on clinical symptoms, recent ECG changes, and a doubling of serum CPK concentrations. The criteria for positive diagnosis from ECG changes were: pathological Q waves, 1 mm ST segment elevation in two or more leads, a new left bundle branch block, or new persisting ST-T changes diagnostic of non-Q wave MI. Serum concentrations of total cholesterol, triglyceride, CPK and LDH were regarded as elevated when they exceeded 5.2 mmol/l, 0.9–1.6 mmol/l, 24–190 u/l, and 230–460 u/l, respectively.

RESULTS

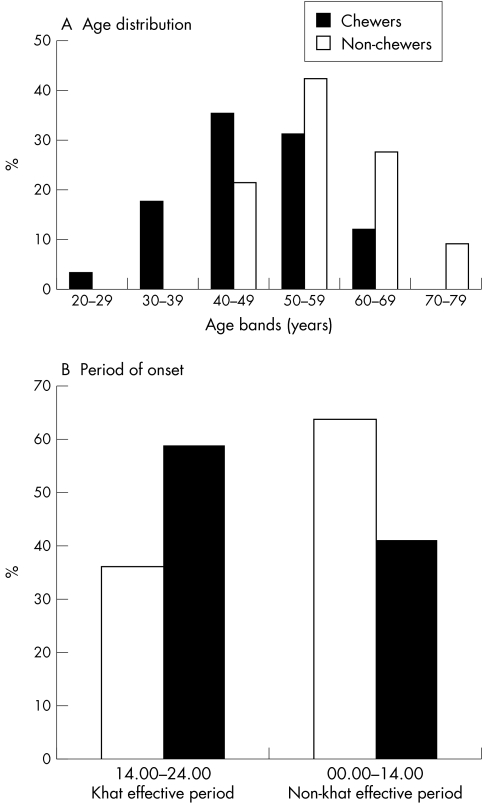

Ninety two per cent of khat chewers consumed khat daily and almost 90% consumed khat for more than three hours daily; 89.8% of patients were male, of which 83% were khat chewers, while 43.7% of female subjects chewed khat. The average age (SEM) and range of khat chewers (47 (9) and 27–60 years) were higher than non-chewers (55 (8) and 40–75 years). Twenty one per cent of khat chewers presenting with AMI were in the 20–29 and 30–39 year age groups, whereas there were none among the non-chewers (fig 1A). The incidence of hypertension or diabetes did not differ between the groups, but more patients had a family history of cardiovascular disease among non-khat chewers (14.8%) than chewers (5.4%). Serum concentrations of CPK and LDH were raised above normal in virtually all patients admitted, confirming the existence of AMI. No differences in the distribution of type of AMI were noted between khat chewers and non-chewers.

Figure 1.

(A) Age band distribution of patients presenting with acute myocardial infarction. Patients were divided into khat chewers (closed histograms) and non-chewers (open histograms). (B) Time of onset of symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. The numbers of patients reporting onset of symptoms during the khat effective period (1400–2400 hours) or non-khat effective period (0000–1330 hours) expressed as a percentage of the total group size.

The most surprising result was a difference in the peak period for presentation with symptoms of AMI between khat chewers and non-chewers. In non-chewers, there was a progressive increase in numbers from 0300 to 0900 hours and after 1500 hours there was a gradual decline until there were none in the last three hours of the day. This confirms the pronounced circadian rhythm in the time of onset of acute myocardial infarction which peaks in the early hours of the day4 and is associated with increased sympathetic outflow and circulating catecholamines producing increases in heart rate, blood pressure, myocardial contractility, and oxygen demand soon after rising. By contrast, in khat chewers the peak period of presentation was during the afternoon, commencing at 1500 hours, continuing until 2100 hours, and then declining towards a trough at 0300 hours. The mean (SEM) time of onset of symptoms was significantly (p < 0.005) later in the khat chewers (1406 (0050) hours) than in the non-chewers (1088 (0092) hours). Since khat chewing sessions usually commence in the early afternoon and may extend into the evening, the khat effective period was defined as 2 pm to 12 midnight. Fifty nine per cent of khat chewers had onset of symptoms during the khat-effective period, compared with only 36.4% of non-khat chewers (fig 1B).

DISCUSSION

Increases in blood pressure and heart rate have been observed in human volunteers after chewing khat which coincide with raised plasma cathinone concentrations,3 the peak occurring at 1.5–3.5 hours.5 Thus, we suggest that the shift in the circadian rhythm is associated with khat chewing. The only other major difference between khat chewers and non-chewers was that 80.6% of khat chewers had an increased desire to smoke tobacco compared with only 15.2% of non-chewers. A uniform pattern of smoking can, however, be assumed throughout the day. The shift in the time of presentation with AMI could not therefore be attributed to the smoking habit but to the khat chewing which occurred only in the afternoon and early evening. The other difference was that serum triglyceride and total cholesterol concentrations were above normal in almost twice the number of non-khat chewers admitted with AMI (27.5% and 24.1%, respectively) than the khat chewers (16.0% and 16.8%). Raised serum lipid concentrations are a recognised risk factor for cardiovascular disease,6 implying that khat chewing and smoking were determinants for precipitating AMI in the khat chewers, while in non-chewers other risk factors such as the raised serum lipids played a role.

Cathinone, the main constituent of khat, is an amphetamine-like substance which releases endogenous catecholamines from peripheral and central neurones. The relation between misuse of amphetamine7 and its analogue, “ecstasy” (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, MDMA),8 and AMI and arrhythmias, respectively, is well documented. Cardiovascular complications from cathinone abuse may therefore be similar to those of amphetamine. AMI could be precipitated by the increased myocardial oxygen demands from cardiac stimulation and peripheral vasoconstriction by cathinone and coronary vasoconstriction. Thus, our study demonstrates that khat chewing is a potential risk factor for AMI, further highlighted by the high proportion of khat chewers with AMI under 45 years of age.

Abbreviations

AMI, acute myocardial infarction

CPK, creatinine phosphokinase

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase

MDMA, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine,

REFERENCES

- 1.Griffiths P. Qat use in London: a study of qat use among a sample of Somalis living in London. Home Office drugs prevention initiative. London: Home Office, 1998.

- 2.Kalix P. Cathinone, a natural amphetamine. Pharmacol Toxicol 1992;70:77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Widler P, Mathys K, Brenneisen R, et al. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of khat: a controlled study. Clin. Pharmacol Ther 1994;55:556–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selwyn AP, Raby K, Vita JA, et al. Diurnal rhythms and clinical events in coronary artery disease. Postgrad Med J 1991;67:S44–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halket JM, Karasu Z, Murray-Lyon IM. Plasma cathinone levels following chewing khat leaves (Catha edulis Forsk.). J Ethnopharmacol 1995;49:111–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shepherd J, Betterridge DJ, Durrington P, et al. Strategies for reducing coronary heart disease and desirable limits for blood lipid concentration: guidelines of the British Hyperlipidaemia Association. BMJ 1987;295:1245–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bashour TT. Acute myocardial infarction resulting from amphetamine abuse: a spasm-thrombus interplay? Am Heart J 1994;128:1237–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henry JA, Jeffries KJ, Dawling S. Toxicity and deaths from 3,4-methylene dioxymethamphetamine (“ecstacy”). Lancet 1992;340:384–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]