Abstract

Objective: To assess the prognostic impact of autonomic activity, as reflected by catecholamines and heart rate variability (HRV), in patients with stable angina pectoris.

Design: Double blind, randomised treatment with metoprolol or verapamil. 24 hour ambulatory ECG, used for frequency domain analyses of HRV, and symptom limited exercise tests at baseline and after one month of treatment. Catecholamine concentrations were measured in plasma (rest and exercise) and urine.

Setting: Single centre at a university hospital.

Patients: 641 patients (449 men) with stable angina pectoris.

Main outcome measures: Cardiovascular (CV) death, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI).

Results: During follow up (median 40 months) there were 27 CV deaths and 26 MIs. Patients who died of CV causes had lower total power and high (HF), low (LF), and very low (VLF) frequency components of HRV. HRV was not altered in patients who suffered non-fatal MI. Catecholamines did not differ between patients with and those without events. Metoprolol increased HRV. Verapamil decreased noradrenaline (norepinephrine) excretion. Multivariate Cox analyses showed that total power, HF, LF, and VLF independently predicted CV death (also non-sudden death) but not MI. LF:HF ratios and catecholamines were not related to prognosis. Treatment effects on HRV did not influence prognosis.

Conclusions: Low HRV predicted CV death but not non-fatal MI. Neither the LF:HF ratio nor catecholamines carried any prognostic information. Metoprolol and verapamil influenced LF, HF, and catecholamines differently but treatment effects were not related to prognosis.

Keywords: heart rate variability, catecholamines, prognosis, angina pectoris

Myocardial ischaemia and autonomic nerve activity are closely related. Sympathetic activation may precipitate ischaemia and ischaemia may lead to neurohormonal activation with increased release of noradrenaline (norepinephrine) from cardiac sympathetic nerves,1 thus setting the scene for a vicious circle. β Blockade is beneficial for patients after myocardial infarction (MI),2 supporting the idea that sympathetic activity exerts a negative influence on prognosis. Reduced heart rate variability (HRV), which is mainly related to reduced cardiac vagal activity,3–5 confers a worsened prognosis after myocardial infarction.6 β Blockade increases HRV,7–9 but it is not known whether this may be related to the improvement of prognosis.

Sympathetic nerve activity may be assessed by measuring noradrenaline in various ways.10,11 In large patient populations, we are restricted to analyses in plasma or urine, since measurements of cardiac noradrenaline spillover require invasive techniques. Noradrenaline concentrations in venous plasma or urine reflect overall sympathetic nerve activity, which may correlate poorly with cardiac sympathetic nerve activity.10 Adrenaline concentrations may reflect cardiac sympathetic nerve activity during stress.10 Low adrenaline and high noradrenaline concentrations in venous plasma were found to confer a poor prognosis in elderly men,12 and venous plasma noradrenaline concentrations are inversely related to prognosis in patients with congestive heart failure.13–15 Prognostic implications of catecholamines in stable angina pectoris have not been evaluated.

Autonomic influences on the sinus node may be studied by analyses of HRV, which reflects the cardiac sympathovagal balance. High frequency (HF) variability is related to vagal nerve activity, whereas low frequency (LF) variability contains components generated by both sympathetic and vagal nerve activity.4,16–18 Adverse prognostic implications of low HRV have been found after MI,6,19,20 in unstable angina,21 and among elderly people without a specific cardiac diagnosis.22 Recently, two studies investigated prognostic implications of HRV in stable angina pectoris23,24 but information on hard end points was limited.

APSIS (Angina Prognosis Study in Stockholm) is a prospective, randomised, single centre study involving double blind treatment of patients with stable angina pectoris with metoprolol or verapamil. Its design and main results have been presented.25 We are evaluating prognostic implications of HRV in the frequency domain, and catecholamines in plasma and in urine. End points were cardiovascular (CV) death and non-fatal MI. We also studied prognostic implications of treatment effects of metoprolol or verapamil on these markers of autonomic activity.

METHODS

Patients

Altogether 1276 patients with a presumed diagnosis of stable angina pectoris were examined at the Heart Research Laboratory at Danderyd Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden. On the basis of medical history and physical examination, 809 patients (561 men) were considered to have stable angina pectoris and were included in the study. This report concerns 641 patients (449 men) with ambulatory ECGs allowing measurement of HRV in the frequency domain at baseline; urinary catecholamine concentrations were measured concomitantly in 551 (386 men) of these patients. The main reason for missing catecholamine data was a freezer breakdown. Results from catecholamine analyses, ambulatory ECG recordings, and exercise tests have been reported in detail elsewhere.26

The ethics committee of the Karolinska Institute approved the study and all participants gave informed consent before participating.

Inclusion criteria were age < 70 years and a history of chronic stable angina pectoris. Chest pain may have been induced by effort or at rest. Patients with mixed angina were included, but not those with unstable angina. Episodes of chest pain or discomfort should have persisted longer than a few seconds but less than 15 minutes. Sublingual nitrates should typically have been providing prompt relief. When there was any doubt that the symptoms were of cardiac origin, additional examinations (perfusion scintigraphy, and radiological or gastrointestinal investigations) were performed. A positive exercise test was not required but could be used for diagnosis. Exclusion criteria were MI within the last three years, anticipated need for revascularisation within one month, significant valvar disease, or severe congestive heart failure (New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class ≥ III).

Because of the risk of rebound phenomena or severe deterioration, patients already being treated with β blockers or calcium antagonists received low dose metoprolol (25–50 mg daily, mean 48 mg) or verapamil (40 mg twice daily) during a two week run-in phase. Thus, 50% were taking metoprolol and 15% were taking verapamil during the baseline investigations. Patients were randomly assigned to double blind treatment irrespective of run-in treatment. The target dose for metoprolol (Seloken ZOC, Astra Hässle, Gothenburg, Sweden) was 200 mg once daily and for verapamil (Isoptin SR, Knoll AG, Ludwigshafen, Germany) 240 mg twice daily, if tolerated. At the end of study, the mean daily doses were 148 mg and 350 mg, respectively.

Catecholamine analyses in plasma and urine

Plasma

Blood was drawn through an indwelling antecubital venous catheter after 15 minutes of supine rest and immediately after exercise. Catecholamines were analysed by high performance liquid chromatography, as previously described and validated.27

Urine

Urine was collected during ambulatory ECG monitoring in separate canisters for day and night and stored at −80°C as previously described.26 Urinary catecholamines were analysed by methods similar to those for plasma analyses.28 To avoid confounding by incomplete urinary sampling, catecholamine excretion was adjusted for creatinine excretion.26 Mean 24 hour catecholamine excretions were calculated as:

|

Ambulatory ECG recordings

Ambulatory ECGs were recorded over 24 hours with the Oxford Medilog system (Oxford Medical Equipment Ltd, Abington, UK) and analysed for ST segment depression as described previously.26 Registrations covering 17–24 hours were adjusted to 24 hours.26 Patients with left bundle branch block (n = 33) or who were being treated with digoxin (n = 21) were excluded.

HRV in the frequency domain was determined by an autoregressive method described by Kay and Marple.29 The ambulatory ECG registrations were divided into five minute epochs. Epochs with more than 4% non-normal RR intervals were excluded. The model order and number of coefficients in the polynomial describing the time series was constantly set to 18. A model order of 12 instead of 18 did not alter the calculations. The mean RR interval of each time series was subtracted and then detrended by applying linear regression.30 The power spectrum of the frequency domain was divided into four frequency bands: total power (≤ 0.4 Hz), very low frequency power (VLF; 0.003–0.04 Hz), LF (0.04–0.15 Hz), and HF (0.15–0.40 Hz), as generally recommended.17 The normalised VLF, LF, and HF were calculated by dividing VLF, LF or HF by (VLF + LF + HF).

Exercise testing

A symptom limited exercise test was carried out on an electrically braked bicycle, starting at 30 W and with 10 W increments every minute, as described previously.26 The test was stopped if there was a fall in systolic blood pressure (≥ 20 mm Hg once or ≥ 10 mm Hg in two consecutive measurements), severe ST segment depression (4–5 mm in at least three leads), or a severe ventricular arrhythmia.

Follow up and definition of end points

Examinations were repeated after patients were taking study drugs for one month. Follow up varied from 6–76 (median 40) months. CV death was defined as death from acute MI, sudden death (within two hours of onset of symptoms), or death from other vascular causes. Criteria for MI were a typical clinical presentation and a significant rise in cardiac enzymes or development of a new Q wave on the ECG (with or without hospitalisation).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean (SD) or median (interquartile range), as appropriate. Continuous variables were compared by Student's t test. HRV data were logarithmically transformed because of skewed distributions. Two factor (time and treatment) analysis of variance or non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney U, Wilcoxon) were also used. Correlations were analysed with Spearman's rank order test. STATISTICA software version 5.1 (StatSoft, Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA) was used. A probability value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Associations between measured variables and events were investigated by univariate proportional hazard (Cox) analyses and Kaplan-Meier plots with χ2 tests and log rank statistics. Since revascularisation (percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting) may influence the proportional risk of an event, patients were censored at the actual dates of procedures. In a second step, variables that showed some relation to events were further evaluated with adjustments for known risk factors (sex, previous MI, hypertension, or diabetes) using the multivariate Cox proportional hazard model. Since signs of ischaemia during exercise testing and ambulatory ECG registration had prognostic importance,31,32 these variables were also included as covariates in our model. Analyses were done according to the principle of intention to treat. Treatment effects were analysed in the same multivariate model using treatment (study drug) and treatment effects (changes in HRV from baseline to one month) as covariates.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows patient characteristics and risk factors. Sixteen of 328 patients in the metoprolol group suffered CV death and 15 a non-fatal MI; corresponding figures for the verapamil group (n = 313) were 11 and 11. Tables 2 and 3 show results of exercise testing, ambulatory ECG, and determinations of plasma and urinary catecholamines concentrations and HRV. Patients who suffered CV death had shorter exercise duration, lower maximal heart rate during exercise, more signs of ischaemia, and lower HRV. However, catecholamine concentrations did not differ.

Table 1.

Risk factors among patients who had an adequate (minimum 17 hours recorded) ambulatory ECG suitable for heart rate variability calculation at baseline, excluding patients treated with digoxin or with left bundle branch block

| No CV death or MI (n=588) | CV death (n=27) | p Value* | Non-fatal MI (n=26) | p Value† | |

| Men (%) | 402 (68) | 25 (93) | 0.008 | 22 (85) | |

| Median age in years (interquartiles) | 60 (54;65) | 61 (58;66) | 64 (60;67) | 0.009 | |

| Current smokers (%) | 130 (21) | 10 (37) | 6 (23) | ||

| Former smokers (%) | 248 (42) | 7 (26) | 10 (38) | ||

| Hypertension (%) | 146 (25) | 14 (52) | 0.002 | 8 (31) | |

| MI (%) | 82 (15) | 10 (37) | 0.001 | 6 (23) | |

| Congestive heart failure (%) | 28 (5) | 4 (15) | 0.022 | 3 (12) | |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 43 (7) | 6 (22) | 0.005 | 5 (23) | 0.027 |

*Comparison between patients suffering cardiovascular (CV) death and patients without CV death or myocardial infarction (MI). †Comparison between patients with a non-fatal MI and patients without CV death or MI. χ2 and Mann-Whitney tests.

Table 2.

Exercise test results and plasma catecholamine concentrations among patients who performed an exercise test and had results from all plasma catecholamine measurements at baseline, excluding those treated with digoxin or with left bundle branch block

| No CV death or MI (n=528) | CV death (n=24) | p Value* | Non-fatal MI (n=21) | p Value† | |

| Adrenaline (nmol/l) | |||||

| Before exercise | 0.17 (0.13) | 0.19 (0.13) | 0.14 (0.10) | ||

| After exercise | 0.68 (0.61) | 0.67 (0.51) | 0.49 (0.34) | ||

| Noradrenaline (nmol/l) | |||||

| Before exercise | 2.43 (1.13) | 2.24 (1.22) | 2.93 (1.39) | ||

| After exercise | 13.55 (7.68) | 14.23 (15.25) | 13.58 (7.79) | ||

| Exercise test results | |||||

| Exercise duration (s) | 617 (219) | 526 (181) | 0.033 | 549 (183) | |

| Heart rate at maximal workload (beats/min) | 135 (23) | 125 (19) | 0.021 | 124 (16) | 0.016 |

| Maximal ST depression (mm) | 1.3 (1.2) | 2.0 (2.0) | 1.6 (1.0) | ||

| ST depression 2 minutes postexercise (mm) | 0.6 (0.7) | 1.4 (1.5) | 0.003 | 0.8 (0.7) |

Data are mean (SD). *Comparison between patients suffering CV death and those without CV death or MI. †Comparison between patients with non-fatal MI and those without CV death or MI. Mann-Whitney test and t test (catecholamines) on log transformed variables.

Table 3.

Urinary catecholamine excretion, signs of ischaemia, and heart rate variability in patients with an ambulatory ECG registration suitable for heart rate variability measurements and with results from all urine catecholamine measurements at baseline, excluding those treated with digoxin or with left bundle branch block

| No CV death or MI (n=503) | CV death (n=23) | p Value* | Non-fatal MI (n=25) | |

| Adrenaline (nmol/mmol creatinine), mean (SD) | ||||

| Daytime | 4.11 (3.42) | 3.56 (2.23) | 3.78 (2.07) | |

| Night time | 1.17 (1.89) | 1.60 (2.37) | 0.87 (0.66) | |

| Calculated 24 hour mean | 3.14 (2.74) | 2.91 (1.91) | 2.81 (1.57) | |

| Noradrenaline (nmol/mmol creatinine), mean(SD) | ||||

| Daytime | 35.11 (13.38) | 31.91 (13.62) | 32.96 (11.63) | |

| Night time | 18.46 (8.18) | 16.29 (8.84) | 17.46 (7.75) | |

| Calculated 24 hour mean | 29.56 (11.03) | 26.70 (11.61) | 27.79 (9.69) | |

| Ambulatory ECG results, median (first and third quartiles) | ||||

| Number of epochs with ST segment depression | 1 (0;7) | 5 (1;19) | 0.016 | 4 (0;9) |

| Duration of ST segment depression (min) | 5 (0;40) | 24 (2;227) | 0.009 | 10 (0;58) |

| Minimal heart rate (beats/min) | 47 (44;52) | 52 (48;58) | 0.002 | 48 (46;52) |

| Heart rate variability, median (first and third quartiles) | ||||

| Mean RR interval (ms) | 845 (769;924) | 804 (741;903) | 865 (799;893) | |

| Total power (ms2) | 1234 (799;1926) | 958 (447;1288) | 0.007 | 1225 (657;1666) |

| VLF (ms2) | 613 (399;876) | 499 (254;843) | 0.057 | 580 (406;849) |

| LF (ms2) | 415 (244;650) | 241 (95;449) | 0.003 | 391 (221;562) |

| HF (ms2) | 172 (99;301) | 81 (59;174) | <0.001 | 137 (108;240) |

| LF:HF ratio | 2.3 (1.7;3.2) | 2.3 (1.7;3.4) | 2.4 (1.6;3.0) | |

| Normalised VLF | 0.47 (0.42;0.52) | 0.53 (0.49;0.58) | <0.001 | 0.48 (0.44;0.53) |

| Normalised LF | 0.35 (0.30;0.39) | 0.30 (0.25;0.37) | 0.004 | 0.34 (0.31;0.36) |

| Normalised HF | 0.17 (0.14;0.21) | 0.16 (0.12;0.19) | 0.088 | 0.17 (0.14;0.21) |

Urinary excretion of catecholamines was measured in nmol/l and adjusted for creatinine excretion. *Comparison between patients suffering CV death and those without CV death or MI. Mann-Whitney U test and t test (catecholamines) on log transformed values.

HF, high frequency power; LF, low frequency power; VLF, very low frequency power.

Effects of treatment on autonomic markers

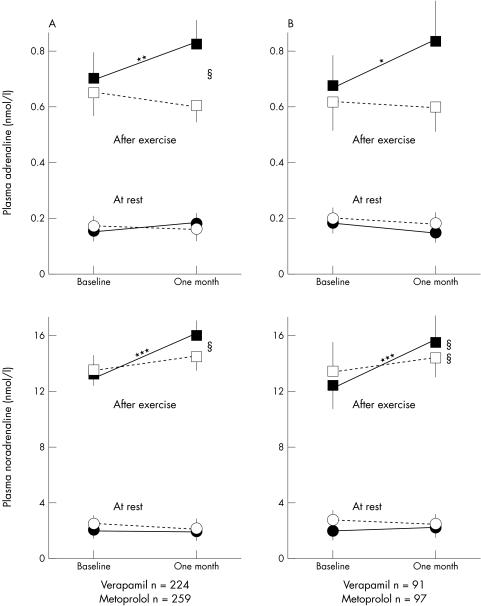

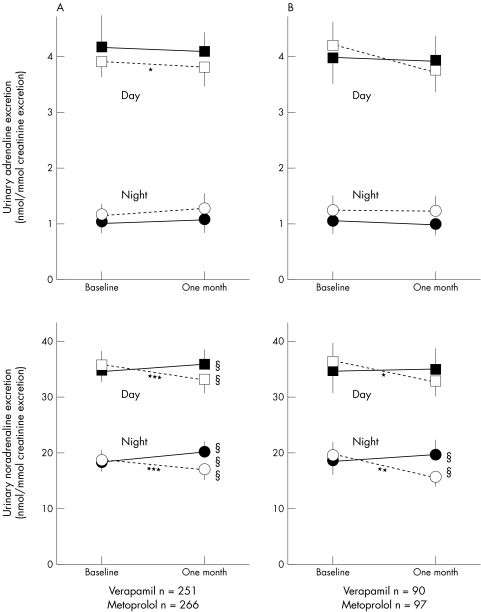

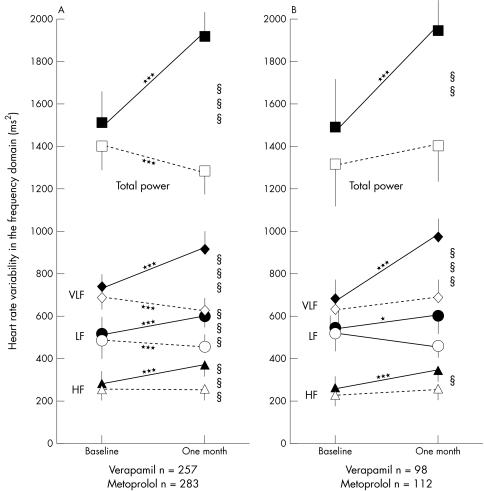

Plasma catecholamine concentrations were higher after exercise with metoprolol than with verapamil treatment (fig 1). Verapamil reduced the urinary excretion of noradrenaline (fig 2). Metoprolol increased total power, VLF, LF, and HF (fig 3). Verapamil did not influence HRV when previously untreated patients were studied (fig 3B). During treatment, total power, VLF, LF, and HF were higher in metoprolol than in verapamil treated patients (fig 3). Both treatments reduced the LF:HF ratio but the effect of metoprolol was significantly greater (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Treatment effects on venous plasma catecholamine concentrations at rest and after exercise for patients who performed an exercise test and had plasma catecholamines measured at baseline and after one month on study drugs. All patients are shown in panel A, and patients without run-in treatment are shown in panel B. Values are mean and 95% confidence interval of the mean. Plasma catecholamines at rest (circles) and after exercise (squares). Open symbols indicate verapamil treated patients and closed symbols metoprolol treated. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 for differences within treatment groups from baseline to one month. §p < 0.05, §§p < 0.01 for differences between treatment groups after one month of study drug treatment.

Figure 2.

Treatment effects on urinary catecholamine excretion during the day and at night for patients with a minimum of 17 hours of ambulatory ECG registration and urinary catecholamine measurements at baseline and after one month on study drugs. All patients are shown in panel A, and patients without run-in treatment in panel B. Values are mean and 95% confidence interval of the mean. Urine catecholamine excretion during the day (squares) and at night (circles). Open symbols indicate verapamil treated patients and closed symbols metoprolol treated. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 for differences within treatment groups from baseline to one month. §§p < 0.01, §§§p < 0.001 for differences between treatment groups after one month on study drug treatment.

Figure 3.

Treatment effects on heart rate variability in the frequency domain for patients with adequate ambulatory ECG registrations both at baseline and after one month on study drugs. All patients are shown in panel A, and patients without run-in treatment are shown in panel B. Values are mean and 95% confidence interval of the mean. Total power (squares); very low frequency (VLF) (diamonds); low frequency (LF) (circles); high frequency (HF), (triangles). Open symbols indicate verapamil treated patients and closed symbols metoprolol treated. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 for differences within treatment groups from baseline to one month. §p < 0.05, §§p < 0.01, §§§p < 0.001 for differences between treatment groups after one month of study drug treatment.

Relation between HRV, ischaemia, and urinary catecholamines

The duration of ambulatory ST segment depression (divided as follows: no ST segment depression, 1–30 minutes, and ≥ 30 minutes) was not related to HRV. Urinary noradrenaline excretion was inversely correlated with all frequency components of HRV (r values between –0.20 and –0.26; p < 0.001) but not with the LF:HF ratio. Adrenaline excretion was not related to HRV.

Prognostic evaluation of catecholamines and HRV

Univariate Cox proportional hazard analyses and Kaplan-Meier plots with χ2 tests and log rank statistics showed no prognostic importance of any catecholamine variable.

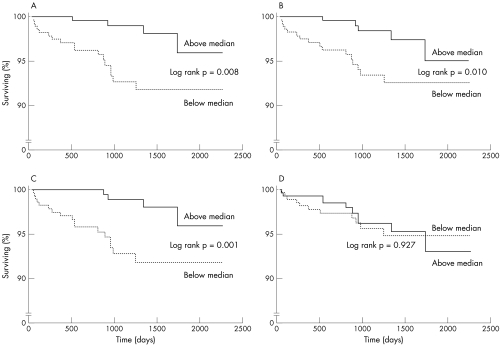

As illustrated by Kaplan-Meier plots (fig 4), all frequency components of HRV at baseline, except the LF:HF ratio, were related to CV death in univariate analyses. Twenty one of 319 patients (7%) with total power below the median (the same applies for LF and HF) suffered CV death compared with 6 of 322 (2%) above the median. No relations were found for non-fatal MI (data not shown). Total power and LF significantly predicted the combined end point (CV death plus MI) but this was due to the relations with CV death alone.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier plots illustrating the risk for cardiovascular death in patients above or below the median for the different frequency domains of heart rate variability measured at baseline. Panel A shows the result for total power, panel B for low frequency (LF), panel C for high frequency (HF), and panel D for the LF:HF ratio. Please note the scale break on the y axis. Solid line = above the median; dotted line = below the median.

Subgroup analyses of patients without prior MI, clinically diagnosed heart failure (NYHA I–II), or diabetes showed that HF was related to CV death. However, only 14 CV deaths occurred in this subgroup. Seven of the 27 CV deaths in the study were sudden. Univariate analyses indicated that patients below the median of the HRV variables, except LF:HF ratio, also had a significantly worsened prognosis for non-sudden CV death.

To evaluate the independent prognostic importance of findings from univariate analyses, we performed multivariate Cox proportional hazard analyses. All frequency components of HRV, but not the LF:HF ratio, carried significant independent prognostic information regarding CV death or CV death plus MI but not regarding MI alone. When mean RR intervals were entered, the frequency domain variables still carried prognostic information. Neither signs of ischaemia during exercise testing or ambulatory ECG registration nor clinically diagnosed congestive heart failure influenced the prognostic importance of any HRV variable. Age and smoking did not influence our findings. Exclusion of patients with prior MI, heart failure, or diabetes gave similar results. Thus, we could not identify important confounding factors for the prognostic information in HRV. Exclusion of patients with angina at rest (presumably vasospastic angina; n = 49) did not alter the results of Kaplan-Meier or Cox analyses.

To avoid confounding effects of “run-in” treatment, data obtained after one month of study drug treatment were also analysed. The results were similar. Treatment and treatment effects (differences in HRV from baseline to one month, the study drug given, and the interaction between these two variables) were also added to our Cox model. Neither the drug given nor the short term effect of treatment carried any independent prognostic information.

DISCUSSION

HRV in all frequency domains, whether obtained at baseline or during treatment, was clearly related to prognosis in the present study of stable angina pectoris. Thus, total power and the HF, LF, and VLF components of HRV independently predicted CV death but not non-fatal MI. Our HRV results agree with previous results in patients after MI6,19,20 and suggest that the prognostic importance of low HRV can be extended to stable ischaemic heart disease.

Interestingly, HF was the HRV variable that appeared to be most strongly related to CV death, whereas neither the LF:HF ratio nor catecholamines, whether assessed in venous plasma or in urine, carried any prognostic significance. There are, however, limitations to catecholamine concentrations in plasma and urine as measures of cardiac sympathetic activity.10 HRV reflects complex interactions and a distinct sympathetic component cannot be distinguished. On the other hand, vagal activity has been shown to influence all measurements of HRV.3,4,17,18 Despite these limitations, it would have been possible to observe some prognostic influence of the LF:HF ratio if cardiac sympathetic activity had been of equal or greater importance.

HRV studies of patients following MI have focused on all cause or cardiac mortality.6,19,20 It is therefore of interest that prediction in the present study was restricted to CV death and did not include non-fatal MI. Van Boven and colleagues23 found that patients with stable angina with events, mainly revascularisations, had lower HRV. Weber and associates24 found a trend towards more combined events (death, non-fatal MI, hospitalisation for unstable angina, revascularisation) in patients with low HRV in the TIBBS study (total ischemic burden bisoprolol study). We used revascularisation as end point in our analyses but found no relations (data not shown), whereas CV death (also non-sudden death) was predicted by HRV. Since we obtained similar results among patients without a prior MI, clinically diagnosed heart failure, or diabetes, our findings appear to be valid for patients with stable angina pectoris regardless of comorbidity.

We found significant, inverse, and moderately strong relations between all frequency domains of HRV and the urinary excretion of noradrenaline but not the excretion of adrenaline or plasma concentrations of either catecholamine. Correlations between HRV and noradrenaline spillover into coronary sinus33,34 or arterial35 plasma have been variable. However, differences may be explained by several factors, such as altered β adrenoceptor sensitivity caused by increased sympathetic drive in congestive heart failure and differences in the sympathetic influence on the sinus node and the rest of the heart (the cardiac sympathetic innervation is more widespread). Furthermore, the vagal components of LF fluctuations of HRV may be important, as discussed above. However, our results are compatible with the view that high overall sympathetic activity is associated with low HRV.

HRV was increased by metoprolol but not by verapamil treatment. Increases in HRV, especially the HF component, have been shown with several β blockers7–9,24,36 and have been attributed mainly to influences on vagal activity.37 The importance of increased cardiac vagal activity in relation to attenuation of sympathetic influences on the sinus node are difficult to assess, as noted above. Postexercise concentrations of catecholamines in plasma were enhanced by metoprolol treatment. However, this probably reflects reduced catecholamine clearance from plasma rather than increased release.38,39 In agreement with this, urinary catecholamine excretion was essentially unchanged during metoprolol treatment. Thus, there was no indication that metoprolol treatment altered overall sympathoadrenal activity in the present study.

Calcium antagonists are a heterogeneous group of drugs and calcium antagonist treatment has yielded variable results with regard to HRV, depending on the drug used.7,24 A study in patients after MI found that verapamil increased the HF component of HRV40 but we could not confirm this. The vasoselective dihydropyridines tend to increase sympathetic activity, measured as noradrenaline concentrations in and spillover to plasma, whereas verapamil tends to lower plasma and urinary noradrenaline.41,42 In a substudy of our patients,43 verapamil lowered plasma noradrenaline by approximately 20%. We found reduced urinary noradrenaline excretion during verapamil treatment but a smaller effect on plasma noradrenaline. This slight discrepancy may be related to more careful attention to methodological aspects in the substudy. Taken together, our results suggest that verapamil treatment slightly reduces whole body sympathetic nerve activity.

Even though treatment with metoprolol and verapamil influenced the autonomic markers in the present study differently, we found no independent prognostic impact of such treatment effects. However, the number of events in our study limits the statistical power of this analysis. Furthermore, the fact that about half of the patients were on low dose metoprolol at baseline may have masked positive relations between treatment effects and outcome. It is of interest that the prognostic information in HRV measurements at one month (during treatment) was similar to that measured at baseline. Still, further research in larger patient groups is needed before definite conclusions regarding the prognostic importance of treatment effects on HRV can be drawn.

Conclusions

HRV in the frequency domain carried important prognostic information regarding the risk for CV death but not for non-fatal MI among patients with stable chronic angina pectoris, which extends previous findings in patients after MI. Thus, low HRV, reflecting alterations in autonomic balance, are also of prognostic importance in patients with stable angina pectoris. A novel finding is that catecholamine concentrations in plasma or urine carried no prognostic information. Treatment with metoprolol or verapamil affected HRV and catecholamine concentrations differently but we were unable to show that these treatment effects have any prognostic significance.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for all help and support from our research nurses Inger Bergbom, Ewa Billing, Ann-Marie Ekman, and Britt Rydén, our laboratory technicians Ann-Katrin Kjerr, Margareta Ring, Maud Daleskog, Maj-Christina Johansson, and Christina Perneby, and Sven V Eriksson MD PhD. We are also grateful to Margret Lundström for data management and Ulf Brodin PhD, Department of Medical Informatics, Karolinska Institutet, for valuable statistical advice.

The study was supported by grants from the Swedish Heart Lung Foundation, the Swedish Medical Research Council (5930), the Foundation of the Serafimer Hospital, the Swedish Society of Medicine, the Karolinska Institute, the Kock Foundation, Trelleborg, Knoll AG, Ludwigshafen, Germany, and Astra Hässle, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Abbreviations

APSIS, Angina Prognosis Study in Stockholm

CV, cardiovascular

HF, high frequency

HRV, heart rate variability

LF, low frequency

MI, myocardial infarction

NYHA, New York Heart Association

TIBBS, total ischemic burden bisoprolol study

VLF, very low frequency

REFERENCES

- 1.Remme WJ. The sympathetic nervous system and ischemic heart disease. Eur Heart J 1998;19(suppl F):F62–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cruickshank JM. The adrenergic system and prevention of myocardial damage by β-blockade: a clinical overview. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1989;14(suppl 9):S20–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akselrod S, Gordon D, Madwed JB, et al. Hemodynamic regulation: investigation by spectral analysis. Am J Physiol 1985;249:H867–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayano J, Sakakibara Y, Yamada A, et al. Accuracy of assessment of cardiac vagal tone by heart rate variability in normal subjects. Am J Cardiol 1991;67:199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huikuri HV. Heart rate variability in coronary artery disease. J Intern Med 1995;237:349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleiger RE, Miller JP, Bigger JT jr, et al and the Multicenter Post-Infarction Research group. Decreased heart rate variability and its association with increased mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1987;59:256–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook JR, Bigger JT jr, Kleiger RE, et al. Effects of atenolol and diltiazem on heart rate variability in normal persons. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991;17:480–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandrone G, Mortara A, Torzilli D, et al. Effects of beta-blockers (atenolol or metoprolol) on heart rate variability after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1994;74:340–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niemelä MJ, Airaksinen KEJ, Huikuri HV. Effects of beta-blockade on heart rate variability in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994;23:1370–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hjemdahl P. Plasma catecholamines: analytical challenges and physiological limitations. Bailléres Clin Endocrinol Metab 1993;7:307–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grassi G, Esler M. How to assess sympathetic activity in humans. J Hypertens 1999;17:719–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen NJ, Schultz-Larsen K. Resting venous plasma adrenaline in 70-year-old men correlated positively to survival in a population study: the significance of the physical working capacity. J Intern Med 1994;235:229–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohn JN, Levine B, Olivari MT, et al. Plasma norepinephrine as a guide to prognosis in patients with chronic congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 1984;311:819–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Francis GS, Benedict C, Johnstone DE, et al for the SOLVD investigators. Comparison of neuroendocrine activation in patients with and without congestive heart failure: a substudy of the studies on left ventricular dysfunction (SOLVD). Circulation 1990;82:1724–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vantrimport P, Rouleau JL, Ciampi A, et al for the SAVE investigators. Two-year time course and significance of neurohormonal activation in the survival and ventricular enlargement (SAVE) study. Eur Heart J 1998;19:1552–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lombardi F. Heart rate variability: a contribution to a better understanding of the clinical role of heart rate. Eur Heart J 1999;1(suppl H):H44–51. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Heart rate variability: standards of measurements, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Circulation 1996;93:1043–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malliani A, Pagani M, Lombardi F, et al. Cardiovascular neural regulation explored in the frequency domain. Circulation 1991;84:482–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bigger JT jr, Fleiss JL, Rolnitzky LM, et al. Frequency domain measurements of heart period variability to assess risk late after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993;21:729–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanza GA, Guido V, Galeazzi N, et al. Prognostic role of heart rate variability in patients with a recent acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1998;82:1323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lanza GA, Pedrotti P, Rebuzzi AG, et al. Usefulness of the addition of heart rate variability to Holter monitoring in predicting in-hospital cardiac events in patients with unstable angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol 1997;80:263–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsuji H, Venditti FJ jr, Manders ES, et al. Reduced heart rate variability and mortality risk in an elderly cohort. The Framingham heart study. Circulation 1994;90:878–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Boven AJ, Jukema JW, Haaksma J, et al on behalf of the REGRESS Study Group. Depressed heart rate variability is associated with events in patients with stable coronary artery disease and preserved left ventricular function. Am Heart J 1998;135:571–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber F, Schneider H, von Arnim T, et al for the TIBBS Investigator Group. Heart rate variability and ischemia in patients with coronary heart disease and stable angina pectoris: influence of drug therapy and prognostic value. Eur Heart J 1999;20:38–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rehnqvist N, Hjemdahl P, Billing E, et al. Effects of metoprolol vs verapamil in patients with stable angina pectoris. The angina prognosis study in Stockholm (APSIS). Eur Heart J 1996,17:76–81. Erratum 1996;17:483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forslund L, Hjemdahl P, Held C, et al. Ischemia during exercise and ambulatory monitoring in patients with stable angina pectoris and healthy controls: gender differences and relationships to catecholamines. Eur Heart J 1998;19:578–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hjemdahl P. Catecholamine measurements in plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. Methods Enzymol 1987;142:521–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hjemdahl P, Larsson T, Bradley T, et al. Catecholamine measurements in urine by high-performance liquid chromatography with amperometric detection: comparison with an autoanalyser fluorescence method. J Chromatogr 1989;494:53–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kay SM, Marple SL. Spectrum analysis: a modern perspective. Proc IEEE 1981;69:1380–419. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jensen-Urstad K, Storck N, Bouvier F, et al. Heart rate variability in healthy subjects is related to age and gender. Acta Physiol Scand 1997;160:235–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forslund L, Hjemdahl P, Held C, et al. Prognostic implications of results from exercise testing in patients with chronic stable angina pectoris treated with metoprolol or verapamil. Eur Heart J 2000;21:901–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forslund L, Hjemdahl P, Held C, et al. Prognostic implications of ambulatory myocardial ischemia and arrhythmias and relations to ischemia on exercise in chronic stable angina pectoris (the angina prognosis study in Stockholm [APSIS]). Am J Cardiol 1999;84:1151–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurita A, Takase B, Hikita H, et al. Frequency domain heart rate variability and plasma norepinephrine levels in the coronary sinus during handgrip exercise. Clin Cardiol 1999;22:207–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kingwell BA, Thompson JM, Kaye DM, et al. Heart rate spectral analysis, cardiac norepinephrine spillover, and muscle sympathetic nerve activity during human sympathetic nervous activation and failure. Circulation 1994;90:234–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adamopoulos S, Piepoli M, McCance A, et al. Comparison of different methods for assessing sympathovagal balance in chronic congestive heart failure secondary to coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 1992;70:1576–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tuininga YS, Crijns HJGM, Brouwer J, et al. Evaluation of importance of central effects of atenolol and metoprolol measured by heart rate variability during mental performance tasks, physical exercise, and daily life in stable postinfarct patients. Circulation 1995;92:3415–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pousset F, Copie X, Lechat P, et al. Effects of bisoprolol on heart rate variability in heart failure. Am J Cardiol 1996;77:612–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hjemdahl P, Åkerstedt T, Pollare T, et al. Influence of beta-adrenoceptor blockade by metoprolol and propranolol on plasma concentrations and effects of noradrenaline and adrenaline during i.v. infusion. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl 1983;515:45–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCance AJ, Forfar JC. Plasma noradrenaline as an index of sympathetic tone in coronary arterial disease: the confounding influence of clearance of noradrenaline. Int J Cardiol 1990;26:335–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pinar E, García-Alberola A, Llamas C, et al. Effects of verapamil on indexes of heart rate variability after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1998;81:1085–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grossman E, Messerli FH. Effects of calcium antagonists on plasma norepinephrine levels, heart rate and blood pressure. Am J Cardiol 1997;80:1453–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hjemdahl P, Wallén NH. Calcium antagonist treatment, sympathetic activity and platelet function. Eur Heart J 1997;18(suppl A):A36–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wallén NH, Held C, Rehnqvist N, et al. Platelet aggregability in vivo is attenuated by verapamil but not by metoprolol in patients with stable angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol 1995;75:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]