Abstract

Background: Despite an overall decline in age adjusted mortality from coronary heart disease in developed countries, the number of patients with heart failure may be increasing.

Objective: To project the future burden of heart failure in Scotland from contemporary epidemiological data.

Methods: Scotland, like many industrialised countries, has an aging though numerically stable population (5.1 million). Current estimates of prevalence, general practice (GP) consultation rates, and hospital admission rates related to heart failure were applied to the whole Scottish population. These estimates were then projected over the period 2000 to 2020, on an age and sex specific basis, using expected changes in the age structure of the Scottish population.

Results: There are currently estimated to be 40 000 men and 45 000 women aged ≥ 45 years with heart failure in Scotland. On the basis of population changes alone, these figures will rise in men and women by 2300 (6%) and 1500 (3%) by year 2005, and by 12 300 (31%) and 7800 (17%) in the longer term (2020), respectively. On the same basis, the annual number of male and female GP visits is likely to rise by 6400 (6%) and 2500 (2%) by year 2005, and by 35 200 (40%) and 17 300 (16%) in the longer term (124 000 and 126 000 visits), respectively. In the year 2000 about 3500 men and 4300 women in Scotland had an incident hospital admission for heart failure. By the year 2020 these figures are likely to increase by 52% (1800 more) and 16% (717 more) in men and women, respectively. If recent trends in short term case fatality rates continue to improve, the number of men who survive this event will increase by 59% (1700 more). Overall, by 2020 the annual number of male and female hospital admissions associated with a principal diagnosis of heart failure is expected to increase by 34% (from 5500 to 7500) and by 12% (from 7800 to 8500), respectively.

Conclusions: Unless rapid and major changes occur in the incidence of heart failure, the burden of this disorder will continue to increase in both primary and secondary care over the next two decades. The greatest increase is likely to occur in men. Future health service planning must take this into account.

Keywords: heart failure, epidemiology, prevalence, trends

Despite an overall decline in age adjusted mortality from coronary artery disease in developed countries, there is evidence to suggest that the number of patients with chronic symptomatic heart disease is increasing.1–3 This is principally the result of two separate trends. First, the proportion of elderly people in the population is rising rapidly and these individuals have the highest incidence of coronary heart disease and hypertension.1–3 Second, survival in those patients with coronary heart disease is improving. For example, we and others have recently shown that survival after acute myocardial infarction has increased notably over the past decade, at least in part because of better medical treatment.4–7 As myocardial infarction is the most powerful risk factor for heart failure, it is likely that the these trends will lead to an increase in the future prevalence of heart failure. It may, therefore, become a more common manifestation of chronic heart disease and an increasing cause of death in such patients.1–3

We have used comprehensive data, routinely collected by the National Health Service (NHS) in Scotland, along with contemporary epidemiological data from elsewhere in the UK, to project the future burden of heart failure in Scotland.

METHODS

Study aims

Our aim in the study was to calculate the current (year 2000), short term (2005), medium term (2010), and longer term (2020) burden of heart failure in Scotland using unique population based data from that country and from other parts of the UK. These data include accurate and contemporary estimates of the population prevalence of heart failure8–10 in addition to rates of heart failure related general practitioner (GP) consultations11 and hospital admissions.12,13

On the basis of projected changes in the demographic structure of the Scottish population, these data were used to estimate the future burden of heart failure in both the community and the hospital sector. As heart failure is essentially confined to older individuals, we studied only those aged ≥ 45 years. On this basis we examined four key variables:

population prevalence of individuals with heart failure (both with and without associated left ventricular systolic dysfunction)

GP consultations per annum related to heart failure

annual total of incident (“first ever”) hospital admissions for heart failure (principal diagnosis) and the proportion of men and women who survive such an admission

annual total of all hospital admissions associated with a principal diagnosis of heart failure.

Data sources

Projected changes in the Scottish population

Age and sex specific mid-year population estimates for Scotland dating from 1980 and projected to 2020 were obtained from official figures published by the registrar general’s office for Scotland.14

Population prevalence of heart failure

Age and sex specific estimates of the population prevalence of individuals with symptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction (one form of chronic heart failure) were derived from two comparable cross sectional studies undertaken by McDonagh and colleagues (Scottish data involving 1640 individuals aged 45–75 years)8 and Morgan and colleagues (English data involving 817 individuals aged 70–84 years).9 Both studies were done in the early 1990s and used echocardiography to determine the presence/absence of left ventricular systolic dysfunction, as well as recording each individual’s symptoms. Importantly, the reported prevalence of heart failure was similar among individuals aged 70–74 years (the only overlap in respect to the age of the two study cohorts). A more recent study from the midlands of England is consistent with these working estimates.10

As many studies have suggested that a third to a half of the patients with symptomatic chronic heart failure have preserved left ventricular systolic dysfunction15 and have comparable morbidity rates to those with impaired systolic function,16,17 we have added an additional one third of cases to the estimated number of cases of symptomatic systolic dysfunction.

General practitioner consultations

Age and sex specific rates of GP consultations per 1000 population were obtained from the Information and Statistics Division of the NHS in Scotland. This division routinely collates data from general practices serving a representative sample of the Scottish population (51 at the time of this analysis). These data are used to compile the Scottish continuous morbidity record.11 All GPs involved in this scheme routinely collect information on each patient consultation, providing a list of diagnoses (including heart failure) relevant to that particular consultation. Recorded information is regularly audited and validated before official entry into the dataset.11 As the current dataset only provides the major cause of consultation, we used relevant Scottish data12 and applied the same ratios observed for primary versus secondary hospital admissions for heart failure (on an age and sex specific basis) to estimate the additional number of GP consultations where heart failure was likely to be a contributory factor.

Scottish hospital admission and survival data

As described previously, the Information and Statistics Division of the NHS in Scotland collects and collates data on all hospital discharges using the Scottish morbidity record scheme.18 Data from patient case records are used to code diagnoses at the time of hospital discharge according to the World Health Organization International classification of disease (ICD) criteria.19 The term “discharge” includes both live discharges and deaths. These data are also linked to information held by the General Register Office for Scotland relating to all deaths within the UK and permit analyses of trends in hospital admission on both a patient and an episode basis, in addition to case fatality rates.12,13,20

Projected burden of heart failure

In order to estimate the current and future burden of heart failure in Scotland all four variables of interest were applied, on an age and sex specific basis, to the projected Scottish population for the period 2000 to 2020.14

In estimating the burden of heart failure within the community, the contemporary rates used to calculate the population prevalence of heart failure and the total number of related GP consultations per annum were held constant. All projected changes in these two variables therefore simply reflect the anticipated changes in the Scottish population over the next 20 years alone.

In estimating the number of “first ever” (incident) hospital admissions, and the total number of admissions associated with a principal diagnosis of heart failure, we assumed that the previously observed trends in hospital rates associated with these types of admission in Scotland for the period 1990 to 199612,13 would remain constant. For example, in Scottish women aged ≥ 45 years there was a relative overall increase of 6% in “first ever” hospital admissions (from 3.3 to 3.5/1000) and in men aged ≥ 45 years a similar 6% overall increase (from 3.5 to 3.7/1000) during this period. Similarly, in order to estimate the number of subjects per annum who survive such an incident heart failure admission and most probably require longer term management within the community, we assumed that the previously observed trends in 30 day case fatality would also continue. For example, during the same period, the proportion of Scottish women aged ≥ 45 years surviving this type of hospital admission beyond 30 days increased by 6% overall (from 3.2 to 3.4/1000). In Scottish men there was an equivalent 3% increase overall (from 3.0 to 3.1/1000).12

RESULTS

The changing structure of the Scottish population

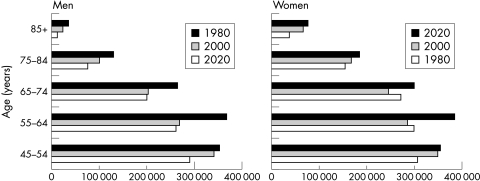

Figure 1 shows the changing structure of the Scottish population (aged ≥ 45 years) between 1980 and 2020.

Figure 1.

An aging population: demographic profile of Scottish men and women aged ≥ 45 years during the period 1980 to 2020.

The number of individuals aged 45–54 years has increased substantially since 1980, with approximately 43 000 (14%) more men and 54 000 (19%) more women in this age group. This largely reflects the impact of the early “baby boomer” population born in the decade following the second world war. Owing to their progressive aging and the likely increased longevity of older individuals, the number of persons ≥ 65 years will increase dramatically in the next 20 years. There will be approximately 105 000 (33%) and 122 000 (28%) more men and women, respectively, aged ≥ 65 years, though the overall size of the population will not change (that is, it will remain approximately 5.1 million).

Projected burden of heart failure within the community

Population prevalence of individuals with heart failure

We estimated that there were approximately 30 000 men and 34 000 women within the Scottish population in the year 2000 who had symptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction (one form of chronic heart failure) requiring medical treatment.8–10 Assuming an additional one third of patients with other forms of heart failure, particularly that associated with preserved left ventricular systolic dysfunction, we estimated that there were an additional 10 000 men and 11 000 women with chronic heart failure in Scotland, giving a total of approximately 40 000 men and 45 000 women aged ≥ 45 years requiring treatment for heart failure in 2000.

With adjustment for expected changes in the demographic structure of the Scottish population but little or no change in the prevalence of heart failure, we estimated that the numbers of men will rise by 2300 (6%), 4900 (12%), and 12 300 (31%) in the short (2005), medium (2010), and longer term (2020), respectively; similarly, we estimated that the numbers of women with heart failure will rise by 1500 (3%), 3100 (7%), and 7800 (17%) in the short, medium, and longer term. In the year 2020, therefore, we estimated that there will be approximately 105 000 individuals in Scotland requiring treatment for heart failure, with almost equal numbers of men and women affected (compared with 85 000 in 2000, a 24% increase).

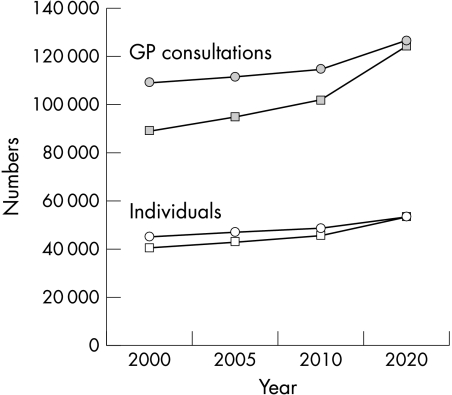

General practice consultations

We estimated that in all there were 89 000 male and 109 000 female GP consultations relating to heart failure in Scotland in the year 2000.11 On the basis of population changes alone, the annual number of male consultations is likely to rise by 6400 (7%), 12 200 (14%), and 35 200 (40%) in the short term (year 2005), medium term (2010), and longer term (2020), respectively. Similarly, we estimated that the annual number of female consultations will increase by 2500 (2%), 5500 (5%), and 17 300 (16%) in the short, medium, and longer term. Owing to the relatively greater increase in older men, the number of GP consultations for heart failure in men will become equivalent to that in women (fig 2).

Figure 2.

Projected population prevalence and annual number of general practitioner (GP) consultations for heart failure in Scotland, 2000 to 2020. Number of individuals with heart failure and number of GP consultations for heart failure (men, squares; women, circles).

Projected burden of heart failure on the hospital sector

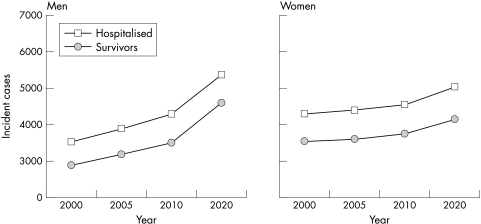

Incident hospital admissions for heart failure

Figure 3 shows the projected number of incident hospital admissions for heart failure (principal diagnosis). By the year 2020 these figures are likely to increase by 52% (1800 more) and by 16% (717 more) in men and women, respectively (from 3500 in men and 4300 in women in the year 2000). Importantly, if at the same time trends in short term case fatality rates remain constant (that is, there is a continued decline in case fatality, particularly in younger age groups), the number of men who survive an incident hospital admission, and therefore probably require longer term medical care, will increase by a greater relative margin of 59% (1700 more). In women, there is likely to be an equivalent increase in those who survive this type of hospital admission (17%; 619 more).

Figure 3.

Estimated number of Scottish men and women who experience an incident hospital admission for heart failure and survive in the short term, 2000 to 2020.

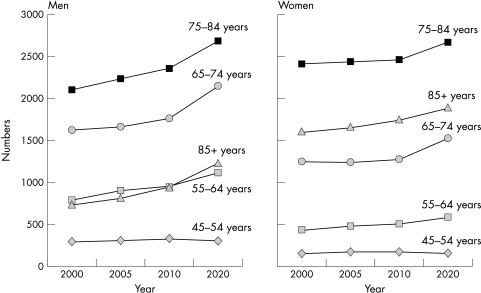

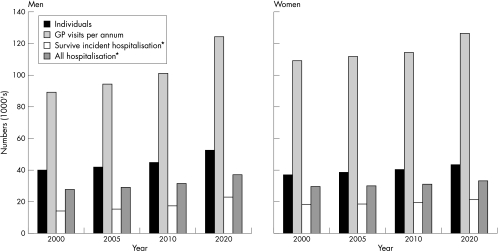

All hospital admissions associated with a principal diagnosis of heart failure

Figure 4 shows the estimated annual number of all hospital admissions (including “first ever”) associated with a principal diagnosis of heart failure, on an age and sex specific basis. The overall number of admissions will increase by 3.5% (468 more), 8.4% (1118 more), and 21% (2864 more) in the short (2005), medium (2010), and longer term (2020), respectively. Owing to greater increases in both the numbers and hospital admission rates in older men relative to older women, the greatest increase will occur in Scottish men—particularly in those aged ≥ 65 years. The total number of male hospital admissions is expected to increase by 34% (from 5500 to 7500 per annum during this period) compared with a 12% increase (from 7800 to 8500) in female admissions.

Figure 4.

Age and sex specific estimates of the annual total of hospital admissions associated with a principal diagnosis of heart failure, 2000 to 2020.

Figure 5 summarises the projected burden of heart failure in Scotland from 2000 to 2020.

Figure 5.

Summary of the projected burden of heart failure in Scotland, 2000 to 2020. Estimated individuals with heart failure and general practitioner visits specific to year.* Figures reflect accumulated number in the previous five years (for example, total number of patients who survived an incident hospital admission 2006 to 2010). “All hospitalisation” refers to incident (“first ever”) and other hospital discharges with heart failure as the principal coding.

DISCUSSION

Our aim in the present analysis was to project the burden of heart failure over the next 20 years. There are several good reasons for attempting such an exercise. First, substantial changes in the population age structure are anticipated in most developed countries, with large increases in the number of very elderly people who are those at greatest risk of developing heart failure.14,21–24 Second, the survival of patients with heart failure has, finally, started to improve13 and hospital admission rates are levelling off.12 Third, there are remarkable changes in the epidemiology of myocardial infarction, the single most powerful predictor of future heart failure.1,4–7 While the incidence of first myocardial infarction is falling, associated survival is increasing.1,4–7 All of these trends have recently been demonstrated in Scotland, as elsewhere.1,4–7 Lastly, contemporary epidemiological studies have also given recent estimates of the prevalence of left ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure in Scotland and England.8–10 Consequently, by bringing together all of these existing analyses relating to the most important public health manifestations of heart failure and risk factors for the development of heart failure, we have been able to project the future burden of this problem (both from a community and secondary care perspective) over the next 20 years.

Our major intention was simply to project the burden of hospital admission 20 years hence by applying recent age and sex specific rates to the expected demographic changes in the Scottish population. Though earlier trends of increasing numbers and rates of hospital admission have slowed recently,12,25 the present analysis still predicts a 21% increase in the number of admissions for heart failure (as the principal discharge diagnosis) by the year 2020. The projected increase is much larger in men (34%) than in women (12%)—reflecting the fact that older men have recently shown greater increases in hospital admission rates and will appear in greater numbers within the overall population relative to older women.

Examination of incident (“first ever”) hospital admissions (that is, factoring out readmissions, which are on the increase12), shows similar trends, namely a 52% increase in men and a 16% increase in women. Clearly, these predictions can be influenced by many factors, including the size of the prevalence pool from which heart failure admissions arise (itself in turn influenced by the incidence of new cases and survival), thresholds for hospital admission, and treatments affecting the need for admission (either first ever admissions or readmissions).

The effect of each of these factors is potentially complex. For example, a treatment may increase survival and reduce the frequency of hospital admission in a given period, but by prolonging life it may increase the overall number of admissions for a given patient. It is also obvious from this example that these different factors interact.

We have, however, attempted to look at one of the most important of these factors—that is, the prevalence pool of patients with heart failure in the community, predominantly those with symptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction (the most common form of heart failure and the type of heart failure for which there is evidence based treatment15). Using the same simple analysis of projecting current rates according to age and sex changes in the population structure, we predict a substantial increase of about one third in the number of men and about one fifth in the number of women with heart failure in the community. Once again, this “prevalence pool” of subjects will be influenced by changes in the survival of existing cases and in the number of incident new cases. Here there are relevant data to factor in. Short term inpatient and longer term (postdischarge) case fatality is falling in patients admitted to hospital with heart failure in Scotland.12,13 This is a credible finding, given the emergence of many new treatments increasing survival in patients with heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction in particular.15

Not only is survival of existing cases of heart failure increasing but the incidence of new cases may not be falling. While the incidence of myocardial infarction (the major precursor of heart failure) is falling, survival is increasing. The overall number of survivors from myocardial infarction in the population is unlikely to change because these two opposing effects cancel each other out.6,7 We believe that it can be further assumed that the incidence of heart failure will not change greatly, as there is no good evidence to show that the proportion of myocardial infarction survivors with left ventricular systolic dysfunction is falling.23 There are, however, other precursors of heart failure such as hypertension, and we have not been able to factor in the influence of changes in prevalence and control of this condition on its future incidence.26 Better treatment of hypertension should reduce the risk of subsequent heart failure (as might better primary and secondary prevention). However, increased survival because of a reduced risk of stroke, renal failure, and myocardial infarction might have the opposite effect in the longer term. The competing risk of other illnesses, especially cancer, in these “extra” long term survivors makes prediction even more difficult.

In addition to the uncertainties already outlined there are other limitations to our analysis. For example, our focus when projecting the future burden of heart failure as the principal discharge coding does not reflect the true burden of heart failure. The number of hospital admissions with heart failure coded in other positions is at least as large as that for admissions with heart failure coded in the primary position. Rates for hospital admission with a secondary coding for heart failure have been rising faster than those with a primary coding—that is, the future number of “secondary admissions” might rise by an even greater amount than primary ones.12,25

Conclusion

In summary, though surrounded by inevitable uncertainty, our projections, based on the best available data, do suggest the burden of heart failure will continue to increase substantially over the next two decades. Future health service planning must take this into account.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from Chief Scientist’s Office, Scottish Executive. SS is supported by the National Heart Foundation of Australia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonneux L, Barendregt MA, Meeter K, et al. Estimating clinical morbidity due to ischemic heart disease and congestive heart failure: the future rise of heart failure. Am J Public Health 1994;84:20–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly DT. Disease burden of cardiovascular disease in the elderly. Coron Artery Dis 1997;8:667–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lampe FC, Morris RRW, Whincup PH, et al. Is the prevalence of coronary heart disease falling in British men? Heart 2001;86:499–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tunstall-Pedoe H, Kuulasmaa K, Mahonen M, et al. Contribution of trends in survival and coronary-event rates to changes in coronary heart disease mortality: 10-year results from 37 WHO MONICA project populations. Monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease. Lancet 1999;353:1547–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg RJ, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, et al. A two-decades (1975 to 1995). Long experience in the incidence, in-hospital and long-term case-fatality rates of acute myocardial infarction: a community-wide perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33:1533–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capewell S, Livingston BM, MacIntyre K, et al. Trends in case-fatality in 117,718 patients admitted with acute myocardial infarction in Scotland. Eur Heart J 2000;21:1883–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capewell S, MacIntyre K, Stewart S, et al. Age, sex and social trends in out-of-hospital cardiac deaths in Scotland 1986–95: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2001;358:1213–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonagh TA, Morrison CE, Lawrence A, et al. Symptomatic and asymptomatic left-ventricular systolic dysfunction in an urban population. Lancet 1997;350:829–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan S, Smith H, Simpson I, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of left ventricular dysfunction among elderly patients in general practice setting: cross sectional survey. BMJ 1999;318:368–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies M, Hobbs F, Davis R, et al. Prevalence of left-ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure in the echocardiographic heart of england screening study: a population based study. Lancet 2001;358:439–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.http://www.show.scot.nhs.uk/isd/primary_care

- 12.Stewart S, MacIntyre K, McCleod ME, et al. Trends in heart failure hospitalisations in Scotland, 1990–1996: an epidemic that has reached its peak? Eur Heart J 2001;22:209–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacIntyre K, Capewell S, Stewart S, et al. Evidence of improving prognosis in heart failure: trends in case fatality in 66 547 patients hospitalized between 1986 and 1995. Circulation 2000;102:1126–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.General Register Office for Scotland. Registrar General’s annual report for 1996. Edinburgh: HSMO, 1997.

- 15.Petrie M, McMurray J. Changes in notions about heart failure. Lancet 2001;358:432–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vasan RS, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, et al. Congestive heart failure in subjects with normal versus reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: prevalence and mortality in a population-based cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33:1948–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Philbin EF, Rocco TA, Lindenmuth NW, et al. Systolic versus diastolic heart failure in community practice: clinical features, outcomes and the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Am J Med 2000;109:605–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kendrick S, Clarke J. The Scottish record linkage system. Health Bull 1993;51:72–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organisation. Manual of the international statistical classification of diseases, injuries and causes of death, 9th revision. Geneva: WHO, 1977.

- 20.Stewart S, MacIntyre K, Hole DJ, et al. More “malignant” than cancer? Five-year survival following a first admission for heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2001;3:315–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McMurray JJ, Petrie MC, Murdoch DR, et al. Clinical epidemiology of heart failure: public and private health burden. Eur Heart J 1998;suppl:9–16. [PubMed]

- 22.McMurray JJ, Stewart S. Epidemiology, aetiology and prognosis of heart failure. Heart 2000;5:596–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guidry UC, Evans JC, Larson MG, et al. Temporal trends in event rates after Q-wave myocardial infarction: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1999;100:2054–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Batchelor WB, Jollis JG, Friesinger GC. The challenge of health care delivery to the elderly patient with cardiovascular disease. Demographic, epidemiologic, fiscal and health policy implications. Cardiol Clin 1999;17:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McMurray J, McDonagh T, Morrison CE, et al. Trends in hospitalization for heart failure in Scotland 1980–1990. Eur Heart J 1993;14:1158–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mosterd A, D’Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, et al. Trends in the prevalence of hypertension, antihypertensive therapy, and left ventricular hypertrophy from 1960 to 1989. N Engl J Med 1999;240:1221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]