Abstract

Objectives: To investigate the relation between coronary flow reserve (CFR), coronary zero flow pressure (Pzf), and residual myocardial viability in patients with acute myocardial infarction.

Designs: Prospective study.

Setting: Primary care hospital.

Patients: 27 consecutive patients with acute anterior myocardial infarction.

Main outcome measures:18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) was used in 27 patients who underwent successful intervention within 12 hours of onset of a first acute anterior myocardial infarction. Within three days before discharge they had < 25% stenosis in the culprit lesion as determined by angiography 24 (3) days after acute myocardial infarction. Pzf and the slope index of the flow-pressure relation (SIFP) were calculated from the simultaneously recorded aortic pressure and coronary flow velocity signals at peak hyperaemia.%FDG was quantified by comparing FDG uptake in the infarct myocardium with FDG uptake in the normal myocardium.

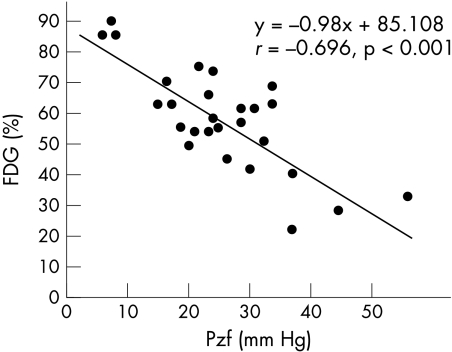

Results: There was a correlation between %FDG and CFR, where y = −1.477x + 62.517, r = −0.072 (NS). There was also a correlation between %FDG and SIFP, where y = −0.975x + 60.542, r = −0.045 (NS), and a significant correlation between %FDG and Pzf, where y = −0.98x + 85.108, r = −0.696 (p < 0.001).

Conclusions: CFR does not correlate with FDG-PET at the time of postreperfusion evaluation of residual myocardial viability. The parameter that correlates best with residual myocardial viability is Pzf and this may be a useful index for predicting patient prognosis.

Keywords: myocardial infarction, blood flow, pressure, myocardial viability

It has previously been reported that, while no improvement in left ventricular function can be detected immediately following reperfusion for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), subsequently left ventricular function does gradually recover.1–4 For this reason, evaluation of residual myocardial viability following reperfusion provides important clues for predicting patient prognosis. The use of positron emission tomography (PET) permits evaluation of the metabolic condition of the infarct myocardium and is the yardstick for assessing myocardial viability.5–10 However, the number of institutions that are able to install and use PET is limited by maintenance cost and other local considerations. Thus, in practice, dobutamine stress echocardiography11,12 and 201thallium reinjection or rest redistribution imaging5,6,11 are used to assess myocardial viability. The relation between gradual recovery of coronary flow reserve (CFR) and improvement in cardiac function in AMI has been described previously13–15 but it is unclear whether CFR also correlates with quantitative evaluation by PET. Also, zero flow pressure (Pzf) may reflect microvascular tone and may increase after AMI.16 However, its exact relation with residual myocardial viability following reperfusion is unclear. In this study, we used quantitative 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET to investigate the relation between CFR, Pzf, and residual myocardial viability following successful angioplasty.

METHODS

Patient enrolment

Our patient population comprised 29 patients admitted to our hospital between September 1999 and April 2001 for a first time acute anterior myocardial infarction and who underwent emergent coronary angiography within 12 hours of the onset of symptoms followed by successful coronary intervention. Under predischarge angiography, all patients also had ≤ 25% stenosis at the culprit lesion and underwent FDG-PET within three days of angiography. Diagnosis of AMI was based on chest pain lasting > 30 minutes, > 1 mm elevation on two or more consecutive leads on ECG, increased creatine kinase concentrations > 2 times the normal value, and MB fraction increase. The following were excluded from the study: patients who had had coronary artery bypass surgery; patients with significant stenosis in a coronary artery other than the infarct related artery; patients whose final TIMI (thrombolysis in myocardial infarction) flow grade was 2 or below; patients who had valve disease symptoms exceeding New York Heart Association functional class II; patients with cardiogenic shock; patients with cardiac hypertrophy on echocardiography; patients with anaemia; patients with insulin dependent diabetes mellitus; and patients who responded suboptimally to treatment for diabetes or hyperlipidaemia. Two patients in whom it was impossible to record coronary flow were also ultimately excluded, leaving a final total of 27. Table 1 shows the findings of clinical and initial angiographic evaluation of these AMI patients. The Osaka City University Hospital Research and Ethics Committee approved the protocol for the study and all patients gave informed written consent before participation.

Table 1.

Clinical and initial angiographic findings of the 27 patients who underwent successful angioplasty

| Patient | Age (years) | Sex | LAD infarct portion | Stenosis severity (%) | Time to angioplasty (hours) | Peak CK (IU/l) | LV global ejection fraction (%) |

| 1 | 48 | M | Mid | 99 | 3.5 | 1080 | 54 |

| 2 | 50 | M | Proximal | 100 | 6 | 8377 | 31 |

| 3 | 75 | M | Mid | 99 | 5.5 | 1789 | 56 |

| 4 | 56 | M | Proximal | 90 | 3 | 1820 | 55 |

| 5 | 50 | M | Mid | 90 | 2 | 536 | 77 |

| 6 | 32 | M | Mid | 100 | 4 | 2240 | 50 |

| 7 | 68 | M | Mid | 100 | 4 | 7480 | 51 |

| 8 | 64 | M | Proximal | 100 | 8 | 4727 | 45 |

| 9 | 66 | M | Proximal | 100 | 3 | 1791 | 57 |

| 10 | 57 | M | Proximal | 90 | 5 | 1680 | 73 |

| 11 | 49 | M | Mid | 100 | 8 | 4530 | 56 |

| 12 | 75 | F | Proximal | 99 | 3 | 1254 | 75 |

| 13 | 77 | M | Proximal | 99 | 6 | 2136 | 55 |

| 14 | 70 | M | Proximal | 100 | 4.5 | 3875 | 56 |

| 15 | 65 | M | Proximal | 90 | 4 | 3540 | 55 |

| 16 | 68 | M | Proximal | 100 | 6 | 8790 | 30 |

| 17 | 67 | F | Proximal | 100 | 4 | 4045 | 54 |

| 18 | 59 | M | Mid | 99 | 4 | 4367 | 53 |

| 19 | 62 | M | Proximal | 100 | 3 | 3867 | 52 |

| 20 | 64 | M | Mid | 99 | 3 | 2569 | 68 |

| 21 | 50 | M | Mid | 90 | 2 | 1021 | 72 |

| 22 | 74 | M | Mid | 99 | 4 | 3475 | 54 |

| 23 | 45 | M | Mid | 100 | 5 | 3560 | 52 |

| 24 | 53 | M | Proximal | 99 | 3 | 2390 | 57 |

| 25 | 65 | M | Proximal | 100 | 3 | 4015 | 54 |

| 26 | 67 | M | Proximal | 100 | 5 | 7230 | 28 |

| 27 | 66 | F | Mid | 90 | 3 | 824 | 75 |

| Mean (SD) | 61 (11) | 4.2 (2.5) | 3445 (2288) | 55 (12) |

CK, creatine kinase; F, female; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LV, left ventricular; M, male.

Coronary intervention

For all patients, we used the femoral artery approach with a 7 or 8 French gauge guiding catheter, an initial bolus of 10 000 U of intravenous heparin, and intracoronary injection of 5 mg isosorbide dinitrate into the culprit coronary artery. In all patients, the culprit lesion was identified in the left anterior descending artery, proximal or mid-portion, before intervention. All patients underwent primary stenting, preceded by balloon predilatation and the use of intravascular ultrasound to measure vessel diameter (media to media) distal to the culprit lesion. A Multi-Link stent (ACS, Santa Clara, California, USA) was then sized to 90% of this diameter and dilated at 14 atm. If residual stenosis was not reduced to ≤ 25%, we selected the next balloon size up and redilated, not concluding the procedure until TIMI 3 flow was obtained. All patients were started on a post-treatment regimen of aspirin 88 mg/day and ticlopidine hydrochloride 200 mg/day.

Predischarge coronary angiography and flow velocity measurement

All patients underwent predischarge angiography by the brachial approach, 24 (3) days after AMI. All medication was stopped at least 24 hours before catheterisation for angiography. An initial intravenous bolus of 3000 U of heparin was followed by intracoronary injection of 5 mg of isosorbide dinitrate into the culprit coronary artery through a 6 French guiding catheter (Brite Tip 0.067 inch, Cordis, Miami, Florida, USA). After confirming that residual stenosis was ≤ 25% and that there was no collateral flow, we began to measure flow velocity. A 0.014 inch coronary Doppler guidewire (FloWire, JOMED, Rancho Cordova, California, USA) was inserted into the left anterior descending coronary artery and its tip inserted to beyond the culprit lesion in a position distal to all septal branches and diagonals. Continuous coronary blood flow velocity profiles were obtained by a 15 MHz pulsed Doppler velocimeter (FloMap, JOMED) along with simultaneous ECG and arterial pressure. After stable signals of coronary blood flow were obtained, 30 μg of intracoronary ATP was administered over 10 seconds and measurements were recorded for five minutes. CFR was calculated as the ratio of mean coronary blood flow velocity obtainable during the peak response to ATP (maximal hyperaemia) to mean coronary blood flow velocity at the basal state.

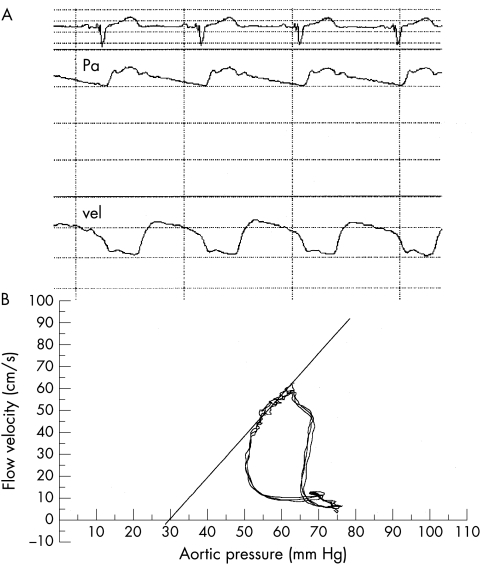

Instantaneous assessment of the flow–velocity relation

We calculated Pzf and the slope index of the flow–pressure relation (SIFP) using the method previously described by de Bruyne and colleagues.17 Figure 1 illustrates how the various indices were derived from pressure and flow velocity recordings. Pzf and SIFP were calculated from the simultaneously recorded aortic pressure and coronary flow velocity signals at peak hyperaemia. The aortic pressure tracing and instantaneous peak coronary blood flow velocity were digitalised with a sample frequency of 125 Hz. The instantaneous relation between coronary flow velocity and coronary pressure during one cardiac cycle was displayed as a velocity–pressure loop calculated by specially designed software. For each beat, the slope of the diastolic portion of the loop was calculated and expressed in cm/s/mm Hg. Pzf was taken as the value where flow on the SIFP line was zero. The diastolic interval of the velocity–pressure loop to be analysed was selected manually from the maximal diastolic velocity to the onset of rapid decline of coronary flow velocity caused by myocardial contraction. The slope values were accepted only when the correlation coefficient of the linear regression between velocity and pressure during the selected diastolic interval was > 0.96, thus eliminating major pressure or velocity tracing distortion. The values reported in this study are the mean values of three consecutive cycles selected during peak hyperaemia.

Figure 1.

Simultaneous pressure and flow velocity tracings during maximal hyperaemia (A) and superimposed instantaneous velocity–pressure loops for three beats (B). The instantaneous hyperaemic diastolic velocity–pressure loop represents the slope of the linear portion of this loop. Pa, aortic pressure; vel, Doppler coronary flow velocity.

PET imaging

A Shimadzu SET 1400 W-10 PET scanner (HEADTOME IV, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) was used for PET Imaging. This scanner can obtain seven slices simultaneously with a 13 mm interval, slice thickness of 11 mm full width at half maximum, and spatial resolution of 4.5 mm full width at half maximum. Axial 6.5 mm interval Z motion of the scanner provided 14 contiguous transverse slices of the myocardium. A 10 minute transmission scan was performed using a rotating germanium 68 rod source. The acquired data were used to correct emission images of FDG for body attenuation. The patient was injected intravenously with 259–370 MBq of FDG 30–60 minutes after the patient’s meal supplemented with a 50 g glucose solution. Forty to 50 minutes was allowed for cardiac uptake of FDG. Static imaging of glucose utilisation at rest was then performed for 10 minutes. Images were collected in 256 × 256 matrices and reconstructed by a computer system (Dr View, Asahi-Kasei Joho System) using Butterworth and ramp filters along the short axis of the heart.

Quantitative analysis of relative uptake of FDG

Each short axis slice was divided into 36 sectors of 10° each and a bull’s eye polar map was reconstructed from the short axis slices extending from the base to the apex. The maximum count in the left ventricle was selected and the value of each pixel was normalised to a maximum count of 100. The left ventricle was divided into nine segments and the mean of normalised counts of each segment was calculated. The mean normalised counts of FDG of apical segment were defined as %FDG. We quantified %FDG by comparing FDG uptake in the infarct myocardium with FDG uptake in the normal myocardium.5,18–21

Wall motion analysis by echocardiography

Regional wall motion was examined one month and six months after the coronary intervention by echocardiography. The left ventricular wall was divided into 16 segments and the regional wall motion of each segment was examined and scored according to a modification of the recommendation of the American Society of Echocardiography,22 which assigns 1 for normal, 2 for hypokinesis, 3 for akinesis, and 4 for dyskinesis.

Statistical analysis

Qualitative data are expressed as frequencies. Continuous variables are expressed as mean (SD). The relation between %FDG of PET and Pzf or other variables was assessed by linear regression analysis. To determine cut off points of Pzf, %FDG, CFR, and SIFP as predictors of left ventricular wall motion recovery, receiver operating characteristic analyses were performed. A χ2 test was used to detect differences between categorical variables. Calculations were made with the use of the Stat View version 5.0 statistical software. Differences were considered significant if p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Wall motion score index

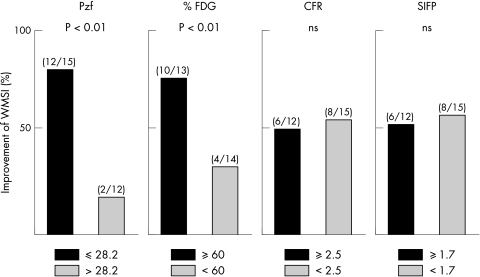

Cut off points of Pzf, %FDG, CFR, and SIFP for left ventricular wall motion recovery, determined by receiver operative characteristic analysis, were 28.2, 60, 2.5, and 1.7, respectively. These cut off points were used, respectively, to divide patients into two groups and to calculate wall motion score index (WMSI) from echocardiograms recorded one month and six months after onset. In the Pzf < 28.2 group, 12 of 15 patients (80%) had improved WMSI six months later, while in the Pzf > 28.2 cohort, 2 of 12 (17%) had improved WMSI (p < 0.01). Of patients with %FDG > 60%, 10 of 13 (77%) had improved WMSI six months later, while only 4 of 14 patients with %FDG < 60% (29%) improved over the same period (p < 0.01). For patients with CFR > 2.5, 6 of 12 (50%) had improved WMSI six months after onset, while 8 of 15 (53%) patients with CFR < 2.5 improved over the same period (NS). For SIFP, of patients with SIFP > 1.7, 6 of 12 (50%) had improved WMSI six months after onset, as did 8 of 15 (53%) patients with SIFP < 1.7 (NS; fig 2).

Figure 2.

Improvement of wall motion score index (WMSI) between one month and six months after coronary intervention. CFR, coronary flow reserve; FDG, 18F-fluorodeoxy-glucose; Pzf, zero flow pressure; SIFP, slope index of the flow–pressure relation.

Correlation between %FDG, CFR, SIFP, and Pzf

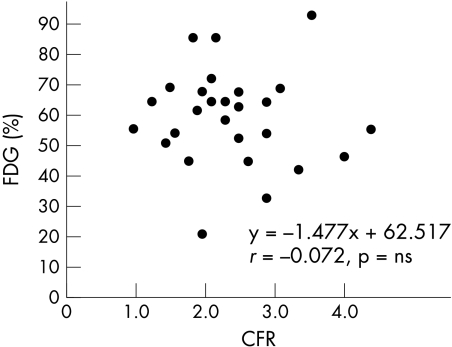

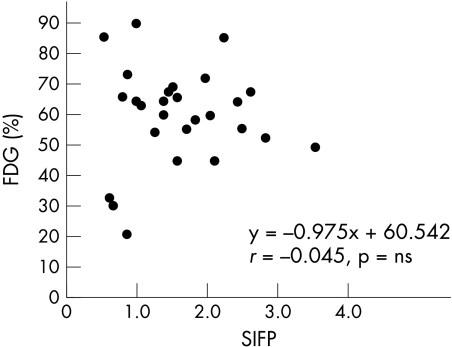

The final patient population was 27, after exclusion of the two patients for whom good coronary flow patterns could not be obtained. We recorded good aortic pressure–flow velocity tracings for all 27 patients. Figure 3 shows the correlation between %FDG and CFR where y = −1.477x + 62.517, r = −0.072 (NS). Figure 4 shows the correlation between %FDG and SIFP, where y = −0.975x + 60.542, r = −0.045 (NS). Figure 5 shows the correlation between %FDG and Pzf, where y = −0.98x + 85.108, r = −0.696, p < 0.001, which is a significant correlation. Pzf alone was significantly correlated with quantitative FDG-PET; CFR and SIFP were not.

Figure 3.

Correlation between the ratio of the maximum count of left ventricular to mean normalised count of infarction area (%FDG) and coronary flow reserve (CFR).

Figure 4.

Correlation between %FDG and the slope index of the flow–pressure relation (SIFP).

Figure 5.

Correlation between %FDG and zero flow pressure (Pzf).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we successfully intervened during the acute phase in 27 consecutive patients with acute anterior myocardial infarction, reducing residual stenosis to 0%. We quantitatively evaluated residual myocardial viability one month after onset with the use of FDG-PET. The parameter derived from the aortic pressure–flow relation that correlated most closely with %FDG was Pzf. CFR and SIFP did not correlate.

CFR and myocardial viability

Several reports suggest that CFR is low immediately after intervention, even in the absence of epicardial artery stenosis. It is similarly reported that CFR may be increased 24 hours or even two weeks after intervention and that it correlates better with other evidence of improved wall motion and myocardial contrast echocardiography.13–15 The possible causes of this may be distal embolisation caused by thrombus or a variety of mechanisms attributable to reperfusion injury, such as compression by tissue oedema,23 platelet plugging,24 neutrophil adhesion,25 damage from free radicals,26 or inappropriate vasoconstriction. The combination of two or more of these factors immediately after acute phase intervention may result in reduced CFR. For this reason, CFR does not accurately reflect the viability of intervention salvaged myocardium immediately after intervention and for about one month. The high CFR observed in some patients in our study, despite almost no myocardial viability, may be attributed to CFR’s lack of correlation with %FDG. Following reperfusion, the infarct territory is a mix of viable and non-viable tissue, with the relative degree of each determining viability.27,28 When there is no stenosis in the epicardial artery, CFR is determined by the response of the microvasculature.

According to Chilian and colleagues, the microvasculature response is as follows: the 120–150 μm pre-arterioles cause the flow dependent vascular dilatory response and the 30–60 μm arterioles produce the myogenic and metabolic response.29,30 Viable myocardium is the aggregate of these flow regulating units. The degree of viability correlates with the total mass of the flow regulating units still working normally. Even in cases where there is very little viable myocardium, if there is no epicardial stenosis, CFR may appear normal because a certain number, however small, of these flow regulating units are functioning normally. In contrast, as CFR is not affected by perfusion bed mass, CFR may correlate closely with simple measures of stenosis severity. Suryapranata and colleagues31 previously reported that CFR assessed immediately after recanalisation is a good predictor of left ventricular wall motion recovery. However, their patient population had a mean peak creatine phosphokinase concentration of 995 IU/l, which is much lower than the mean of 3455 IU/l of our own myocardial infarction population. Ten days after onset, 20 of 22 patients in the study of Suryapranata and colleagues had improved wall motion, whereas in our study this was true of only 14 of 27 patients at six months. It may well be that in patients with this degree of residual viability, CFR correlates well with myocardial viability. Another very important factor is that CFR is heavily influenced by haemodynamic factors at the time it is measured, such as blood pressure and heart rate.32

SIFP, Pzf, and myocardial viability

Experimental studies have shown that the SIFP is superior to CFR for the assessment of directional changes in coronary conductance because of its independence of haemodynamic conditions at the time of assessment.33 However, unlike CFR, SIFP is influenced and altered by perfusion bed mass. In our study, we found no correlation between SIFP and infarct myocardial viability. Very few reports have dealt with the clinical significance of Pzf immediately after AMI. We believe this is the first report of an investigation of the relation between Pzf and myocardial viability. Increased Pzf may reflect accentuation of microvascular tone and decreased perfusion bed mass caused by non-viable tissue may be a cause of accentuation of microvascular tone. It has also been reported that the no reflow phenomenon in patients with AMI following reperfusion may be associated with improvement in wall motion and left ventricular remodelling.34,35 Recent attention has focused on treatments that reduce, even slightly, the incidence of no reflow.36,37 Terai and colleagues have even suggested in their study detailing significantly increased Pzf in no reflow patients that increased Pzf is the mechanism of the no reflow phenomenon.16 We have not touched on this in our study but suspect that the no reflow area may correlate with Pzf and %FDG.

Study limitations

Our study may be said to have the following limitations:

Our patient population comprised only 27 subjects; a larger number is required to confirm the clinical usefulness of our results.

It is not clear whether FDG-PET study one month after onset of AMI fully reflects residual myocardial viability. Additional long term PET study may be required to confirm the accuracy of these results.

We used aortic pressure at the guiding catheter to obtain Pzf and SIFP but it is not clear whether this pressure is the same as coronary perfusion pressure.

We extrapolated from a straight line to determine Pzf. The segment of the diastolic pressure–flow velocity loop from which this line has been extrapolated is very short, making the chance of error very large.

Ideally, we should have extrapolated Pzf after induction of a very long diastole as described by Di Mario and colleagues.38 However, Nanto and associates39 have shown that Pzf calculated from the coronary pressure–flow relation during a normal cardiac cycle under vasodilatation correlated well with that during the long diastole (r = 0.75, p < 0.01).For patients who have had an AMI, however, causing a long pause in the subacute phase entails a risk of cerebral infarction and could not be considered for all patients in our population. We believe that this method is safe in the clinical setting.

In North America and Europe, patients are largely expected to be discharged within 10 days of an AMI. From the point of view of clinical usefulness, Pzf must be calculated immediately after intervention but, as has been said, the acute phase of AMI is often characterised by distal embolisation caused by thrombus or a variety of other mechanisms caused by reperfusion injury, such as compression by tissue oedema, platelet plugging, neutrophil adhesion, damage from free radicals, or inappropriate vasoconstriction. The combination of two or more of these factors immediately after acute phase intervention may result in reduced CFR or increased Pzf. In this study, we tried as much as possible to exclude the influence of these factors from our results to elucidate the correlation between myocardial viability, CFR, and Pzf.

Conclusions

Pzf is easily extrapolated and calculated in the catheterisation laboratory with the use of a Doppler guidewire and is not greatly influenced by haemodynamics. In patients successfully reperfused for AMI, CFR does not correlate with FDG-PET at the time of relatively early postreperfusion evaluation of residual myocardial viability. The parameter that correlates best with residual myocardial viability is Pzf and this may be a useful index for predicting patient prognosis following AMI.

Abbreviations

AMI, acute myocardial infarction

CFR, coronary flow reserve

FDG, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose

PET, positron emission tomography

Pzf, zero flow pressure

SIFP, slope index of the flow-pressure relation

TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction

REFERENCES

- 1.Touchstone DA, Beller GA, Nygaard TW, et al. Effects of successful intravenous reperfusion therapy on regional myocardial function and geometry in humans: a tomographic assessment using two-dimensional echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 1989;13:1506–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stack RS, Phillips HR 3d, Grierson DS, et al. Functional improvement of jeopardized myocardium following intracoronary streptokinase infusion in acute myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest 1983;72:84–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheehan FH, Doerr R, Schmidt WG, et al. Early recovery of left ventricular function after thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: an important determinant of survival. J Am Coll Cardiol 1988;12:289–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reduto LA, Freund GC, Gaeta JM, et al. Coronary artery reperfusion in acute myocardial infarction: beneficial effects of intracoronary streptokinase on left ventricular salvage and performance. Am Heart J 1981;102:1168–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonow RO, Dilsizian V, Cuocolo A, et al. Identification of viable myocardium in patients with chronic coronary artery disease and left ventricular dysfunction. Comparison of thallium scintigraphy with reinjection and PET imaging with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose. Circulation 1991;83:26–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamaki N, Ohtani H, Yamashita K, et al. Metabolic activity in the areas of new fill-in after thallium-201 reinjection: comparison with positron emission tomography using fluorine-18-deoxyglucose. J Nucl Med 1991;32:673–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kambara H, Nohara R, Tamaki N, et al. Positron emission tomography: usefulness in assessing myocardial viability. Jpn Circ J 1992;56:608–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunken R, Schwaiger M, Grover-McKay M, et al. Positron emission tomography detects tissue metabolic activity in myocardial segments with persistent thallium perfusion defects. J Am Coll Cardiol 1987;10:557–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czernin J, Porenta G, Brunken R, et al. Regional blood flow, oxidative metabolism, and glucose utilization in patients with recent myocardial infarction. Circulation 1993;88:884–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamaki N, Kawamoto M, Tadamura E, et al. Prediction of reversible ischemia after revascularization. Perfusion and metabolic studies with positron emission tomography. Circulation 1995;91:1697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takagi T, Yoshikawa J, Yoshida K, et al. Detection of hibernating myocardium in patients with myocardial infarction by low-dose dobutamine echocardiography: comparison with thallium-201 scintigraphy with reinjection. J Cardiol 1995;25:155–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cigarroa CG, deFilippi CR, Brickner ME, et al. Dobutamine stress echocardiography identifies hibernating myocardium and predicts recovery of left ventricular function after coronary revascularization. Circulation 1993;88:430–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishihara M, Sato H, Tateishi H, et al. Time course of impaired coronary flow reserve after reperfusion in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1996;78:1103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lepper W, Hoffmann R, Kamp O, et al. Assessment of myocardial reperfusion by intravenous myocardial contrast echocardiography and coronary flow reserve after primary percutaneous transluminal coronary angiography in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2000;101:2368–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neumann FJ, Kosa I, Dickfeld T, et al. Recovery of myocardial perfusion in acute myocardial infarction after successful balloon angioplasty and stent placement in the infarct-related coronary artery. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;30:1270–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terai K, Ito H, Sugimoto K, et al. Mechanism of no reflow phenomenon in patients with acute myocardial infarction: its impact on coronary zero flow pressure and flow pressure slope index [abstract]. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:351A. [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Bruyne B, Bartunek J, Sys SU, et al. Simultaneous coronary pressure and flow velocity measurements in humans. Feasibility, reproducibility, and hemodynamic dependence of coronary flow velocity reserve, hyperemic flow versus pressure slope index, and fractional flow reserve. Circulation 1996;94:1842–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sawada SG, Allman KC, Muzik O, et al. Positron emission tomography detects evidence of viability in rest technetium-99m sestamibi defects. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994;23:92–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossetti C, Landoni C, Lucignani G, et al. Assessment of myocardial perfusion and viability with technetium-99m methoxyisobutylisonitrile and thallium-201 rest redistribution in chronic coronary artery disease. Eur J Nucl Med 1995;22:1306–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan RK, Lee KJ, Calafiore P, et al. Comparison of dobutamine echocardiography and positron emission tomography in patients with chronic ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cadiol 1996;27:1601–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baer FM, Voth E, Deutsch HJ, et al. Predictive value of low dose dobutamine transesophageal echocardiography and fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography for recovery of regional left ventricular function after successful revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;28:60–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shiller NB, Shah PM, Crawford M, et al. Recommendations for quantitation of the left ventricle by two-dimensional echocardiography: American Society of Echocardiography committee on standards, subcomitte on quantitation of two-dimensional echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1989;2:358–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tranum JJ, Janse MJ, Fiolet WT, et al. Tissue osmolality, cell swelling, and reperfusion in acute regional myocardial ischemia in the isolated porcine heart. Circ Res 1981;49:364–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feinberg H, Rosenbaum DS, Levitsky S, et al. Platelet deposition after surgically induced myocardial ischemia. An etiologic factor for reperfusion injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1982;84:815–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chatelain P, Latour JG, Tran D, et al. Neutrophil accumulation in experimental myocardial infarcts: relation with extent of injury and effect of reperfusion. Circulation 1987;75:1083–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ambrosio G, Becker LC, Hutchins GM, et al. Reduction in experimental infarct size by recombinant human superoxide dismutase: insights into the pathophysiology of reperfusion injury. Circulation 1986;74:1424–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schofer J, Mathey DG, Montz R, et al. Use of dual intracoronary scintigraphy with thallium-201 and technetium-99m pyrophosphate to predict improvement in left ventricular wall motion immediately after intracoronary thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1983;2:737–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson LL, Seldin DW, Keller AM, et al. Dual isotope thallium and indium antimyosin SPECT imaging to identify acute infarct patients at further ischemic risk. Circulation 1990;81:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chilian WM. Coronary microcirculation in health and disease. Summary of an NHLBI workshop. Circulation 1997;95:522–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chilian WM, Kuo L, DeFily DV, et al. Endothelial regulation of coronary microvascular tone under physiological and pathophysiological conditions. Eur Heart J 1993;14:55–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suryapranata H, Zijlstra F, MacLeod DC, et al. Predictive value of reactive hyperemic response on reperfusion on recovery of regional myocardial function after coronary angioplasty in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 1994;89:1109–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klocke-FJ. Measurements of coronary flow reserve: defining pathophysiology versus making decisions about patient care. Circulation 1987;76:1183–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cleary RM, Moore NB, DeBoe SF, et al. Sensitivity and reproducibility of the instantaneous hyperemic flow versus pressure slope index compared to coronary flow reserve for the assessment of stenosis severity. Am Heart J 1993;126:57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brochet E, Czitrom D, Karila CD, et al. Early changes in myocardial perfusion patterns after myocardial infarction: relation with contractile reserve and functional recovery. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;32:2011–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ito H, Okamura A, Iwakura K, et al. Myocardial perfusion patterns related to thrombolysis in myocardial infarction perfusion grades after coronary angioplasty in patients with acute anterior wall myocardial infarction. Circulation 1996;93:1993–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Assali AR, Sdringola S, Ghani M, et al. Intracoronary adenosine administered during percutaneous intervention in acute myocardial infarction and reduction in the incidence of “no reflow” phenomenon. Cathet Cardiovasc Interv 2000;51:27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ito H, Taniyama Y, Iwakura K, et al. Intravenous nicorandil can preserve microvascular integrity and myocardial viability in patients with reperfused anterior wall myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33:654–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Mario C, Krams R, Gil R, et al. Slope of the instantaneous hyperemic diastolic coronary flow velocity-pressure relation. Circulation 1994;90:1215–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nanto S, Masuyama T, Takano Y, et al. Determination of coronary zero flow pressure by analysis of the baseline pressure-flow relationship in humans. Jpn Circ J 2001;65:793–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]