Abstract

Background: Mitral annular calcification has been associated with various systemic and cardiac diseases, with a higher prevalence in women and patients over 70. A possible association between mitral annular calcification and coronary artery disease has recently been suggested.

Objective: To determine the prevalence of severe coronary artery disease in younger patients with mitral annular calcification.

Methods: Consecutive patients aged ≤ 65 years with and without mitral annular calcification as detected by echocardiography were identified from a prospective clinical database. Only patients with a coronary angiogram done within one year of their qualifying echocardiogram were analysed. Severe coronary artery disease was defined as ≥ 70% stenosis of at least one major epicardial coronary artery.

Patients: 17 735 patients were screened. Of these, 6207 (35%) had mitral annular calcification and 885 (5%) were also ≤ 65 years old; coronary angiography was done in 100 of the latter (64 men; 36 women), mainly for anginal symptoms or a positive stress test. A control group (n = 121; 88 men, 33 women) was identified from 2840 consecutive patients screened. There was no significant difference between the groups in patient characteristics, indication for angiography, or atherosclerotic risk factors.

Results: Angiography showed a higher prevalence of severe coronary artery disease in patients with mitral annular calcification than in those without (88% v 68%, p = 0.0004), and a higher prevalence of left main coronary artery disease (14% v 4%, p = 0.009) and triple vessel disease (54% v 33%, p = 0.002). The positive predictive value of mitral annular calcification for finding severe coronary artery disease was 92%.

Conclusions: In patients aged ≤ 65 years, mitral annular calcification is associated with an increased prevalence of severe obstructive coronary artery disease. It may serve as a useful echocardiographic marker for the presence of obstructive coronary artery disease, especially when associated with anginal symptoms.

Keywords: mitral annular calcification, coronary angiography, echocardiography

Mitral annular calcification is a chronic degenerative process, progressing with advancing age. It is more common in women and in people over 70 years old.1–3 As previously reported,4,5 mitral annular calcification may result in mitral stenosis, mitral regurgitation, infective endocarditis, atrial arrhythmias, and heart block. It is one of the known independent risk factors for systemic embolism and stroke, and its severity—as measured by the thickness of the valve in M mode—is linearly correlated with the risk of stroke.5

An increased prevalence of mitral annular calcification has also been found in patients with systemic hypertension, increased mitral valve stress, mitral valve prolapse, raised left ventricular systolic pressure, aortic valve stenosis, chronic renal failure, secondary hyperparathyroidism, and atrial fibrillation.3–5 Along with other calcific valvar processes, mitral annular calcification is associated with a high prevalence of risk factors for the development of coronary atherosclerosis.3–11 As such, it may also be a manifestation of generalised atherosclerosis in the elderly population.3,12 However, age is more closely related to this condition and to other forms of valvar calcification than any other factors, and this may strengthen its association with coronary artery disease in a younger population.3,10,13 Recently, Adler and colleagues found that mitral annular calcification was a marker of a high prevalence and severity of coronary artery disease in patients with a mean age of 70 years undergoing coronary angiography.7

The clinical significance of mitral annular calcification in a selected population of younger patients has not yet been defined. Our aim in this study was to determine whether there is a correlation between the presence of mitral annular calcification on echocardiography and the finding of significant obstructive coronary artery disease on cardiac catheterisation in patients aged less than 65 years. In such a relatively young group of patients, mitral annular calcification may serve as an important and specific marker of severe coronary artery disease.

METHODS

The Institutional Review Board of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center approved the study.

We screened the computer database of the echocardiography laboratory from January 1995 to December 1998 for patients with a diagnostic code of mitral annular calcification and from these we selected patients aged ≤ 65 years. We then studied only patients who had a coronary angiography within one year of the qualifying echocardiogram. A control group (patients without mitral annular calcification) was selected from the same database using the same methods. In the selection procedure, the absence of mitral annular calcification was the only criterion that differed between the groups.

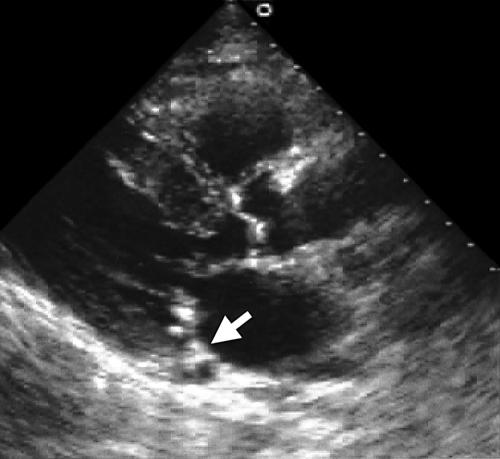

The diagnosis of mitral annular calcification was by M mode and cross sectional transthoracic echocardiography. Three highly experienced echocardiologists interpreted the echocardiograms. On M mode echocardiography the diagnosis depended on the appearance of an echo-dense band throughout systole and diastole, which was easily distinguishable from the posterior mitral leaflet and was located behind the posterior leaflet and anterior to the left ventricular posterior wall. On cross sectional echocardiography (fig 1), the diagnosis was made by the presence of an intense echo producing structure located at the junction of the atrioventricular groove and posterior mitral valve leaflet on the parasternal long axis, apical four chamber, or parasternal short axis views.

Figure 1.

Cross sectional echocardiography of patient with mitral annular calcification, showing presence of an intense echo producing structure located at the junction of the atrioventricular groove and posterior mitral valve leaflet.

The presence of coronary artery disease was determined by coronary angiography. Cardiologists trained in coronary angiography and unaware of the echocardiographic results interpreted the studies visually. “Significant coronary artery disease” was defined as any stenosis of ≥ 70% in at least one major epicardial coronary artery, or ≥ 50% in the left main coronary artery.

The demographic and clinical data were obtained from the patients’ records. Patients were considered to have diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia, and hypertension if they were currently on specific medical or pharmacological treatment. They were defined as smokers if they were currently smoking or had quit smoking within the previous five years.

Statistical analysis

Numerical values are reported as mean (SD) or as a proportion of the sample size. Comparisons between the group with mitral annular calcification (index group) and the control group were made with the χ2 test for categorical data and Student’s t test for continuous data. Multivariate analysis was used to identify predictors for coronary artery disease. The following variables were entered into the model: age ≥ 60, sex, mitral annular calcification, chest pain, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, and smoking.

RESULTS

Of 17 735 patients screened, 6207 (35%) were diagnosed as having mitral annular calcification. Of those, 885 (5%) were aged ≤ 65 years. One hundred patients (36 women, 64 men; mean (SD) age 59 (7) years, range 28–65 years, median 62 years) had mitral annular calcification, were ≤ 65 years old, and underwent angiography within one year of the diagnostic transthoracic echocardiography. These patients comprised the study group.

The control group comprised 121 consecutive patients from the same database. These patients (33 women, 88 men; mean age 56 (8) years, range 29–65 years, median 58 years) had no mitral annular calcification, were ≤ 65 years old, and underwent angiography within one year of the diagnostic transthoracic echocardiography.

The patients’ clinical characteristics are presented in table 1. There were no significant differences between the groups in risk factors or clinical presentation (71% of the control group and 79% of the index group had angina pectoris as an indication for angiography, p = 0.18). Other indications for angiography (evaluation of heart failure and cardiomyopathy and assessment before valvar or major vascular surgery) were not different between the two groups.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients with and without mitral annular calcification

| MAC (n=100) | No MAC (n=121) | p Value | |

| Age (years) (mean (SD)) | 59 (7) | 56 (8) | 0.22 |

| Male sex | 64 (64) | 88 (73) | 0.16 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 34 (34) | 30 (25) | 0.13 |

| Hypertension | 42 (42) | 58 (48) | 0.38 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 37 (37) | 54 (45) | 0.25 |

| Smoking | 18 (18) | 31 (26) | 0.17 |

| CRF | 9 (9) | 6 (5) | 0.23 |

| CABG | 39 (39) | 42 (35) | 0.51 |

| PCI | 26 (26) | 49 (40) | 0.024 |

| Chest pain | 79 (79) | 86 (71) | 0.18 |

Values are n (%) unless specified.

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CRF, chronic renal failure; MAC, mitral annular calcification; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Thirty five patients in the control group had undergone angiography for indications other than chest pain or unstable angina, compared with 21 patients in the index group. Only six of the asymptomatic control patients (15%) had obstructive coronary artery disease, compared with 15 (72%) in the index group (p < 0.0001). Moreover, 99 of 111 patients with angina (89%) had mitral annular calcification, compared with only 71 of 110 without angina (64%) (p < 0.0001). Patients in the control group had undergone significantly more percutaneous coronary interventions than patients in the index group (40% v 24%, p = 0.024).

Angiographic findings

We found significantly more obstructive coronary artery disease in patients in the index group than in the control group (88% v 68%, p = 0.0004). As shown in table 2, patients in the index group had a higher prevalence of significant left main coronary artery stenosis (14% v 4%, p = 0.009) and a higher prevalence of triple vessel coronary artery disease (54% v 33%, p = 0.002). The prevalence of double and single vessel disease was not different between the two groups.

Table 2.

Angiographic findings in patients with and without mitral annular calcification

| MAC (n=100) | No MAC (n=121) | p Value | |

| LM stenosis | 14 (14) | 5 (4) | 0.009 |

| TVD | 54 (54) | 40 (33) | 0.002 |

| DVD | 17 (17) | 12 (10) | 0.12 |

| SVD | 17 (17) | 30 (25) | 0.16 |

| No significant CAD | 12 (12) | 39 (32) | 0.0004 |

Values are n (%).

DVD, double vessel disease; LM, left main coronary artery; MAC, mitral annular calcification; SVD, single vessel disease; TVD, triple vessel disease.

Mitral annular calcification according to sex

We analysed our data according to sex and did not find that mitral annular calcification was a predictor of significant coronary artery disease in men. There were 34 women in the index group, and of those only six (18%) had non-significant coronary stenosis or angiographically normal coronary arteries, compared with 18 of 33 women in the control group (54%) (p = 0.002). Thus the absence of mitral annular calcification was a significant marker for the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease in women but not in men. There were no significant differences between the two groups of women with regard to age or risk factor profile.

Multivariate analysis

As presented in table 3, we found on multivariate analysis that hyperlipidaemia (p = 0.002), mitral annular calcification (p = 0.02), chest pain (p = 0.02), smoking (p = 0.05), age ≥ 60 (p = 0.04), and male sex (p = 0.02) were independent predictors of the presence of significant coronary artery disease. The presence of mitral annular calcification on transthoracic echocardiography was found to have a 92% positive predictive value for the presence of significant coronary artery disease, while the absence of mitral annular calcification had a 49% negative predictive value.

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of the factors associated with the presence of significant coronary artery disease

| Factor | p Value | OR | 95% CI |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 0.004 | 3.56 | 1.03 to 8.36 |

| Male sex | 0.01 | 2.95 | 1.28 to 6.80 |

| MAC | 0.02 | 2.92 | 1.14 to 7.47 |

| Smoking | 0.05 | 2.87 | 0.98 to 8.41 |

| Chest pain | 0.025 | 2.79 | 1.14 to 6.83 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.11 | 2.19 | 0.83 to 5.78 |

| Age ≥60 years | 0.03 | 2.14 | 1.02 to 4.47 |

| CRF | 0.27 | 0.42 | 0.09 to 1.96 |

CI, confidence interval; CRF, chronic renal failure; MAC, mitral annular calcification; OR, odds ratio

DISCUSSION

The main finding of our study is that mitral annular calcification is an independent predictor of the presence of severe stenosis (≥ 70% diameter stenosis) in at least one major epicardial coronary artery on angiography in patients presenting with chest pain under the age of 65. Moreover, mitral annular calcification is an indicator of a higher prevalence of triple vessel disease or significant left main coronary artery stenosis in this specific group of patients. In women under 65 years of age, the absence of mitral annular calcification was an indicator of the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease.

The prevalence of both mitral annular calcification and coronary artery disease is known to increase with age.3 In 1992, Benjamin and colleagues first reported an increased incidence of coronary artery disease from the Framingham database.5 They found that patients with mitral annular calcification had a higher prevalence of coronary artery disease than a control group (28.8% v 17.4%, p = 0.006). Subsequently, it was shown that patients with mitral annular calcification had a significantly higher prevalence of aortic atheroma than matched controls.6,7 Protruding atheromas and an atheroma thickness > 4 mm were also more prevalent in individuals with mitral annular calcification. These findings may in part explain the increased risk of stroke in the presence of mitral annular calcification. It was then hypothesised that various calcification processes (for example, aortic valve calcification, mitral annular calcification, coronary artery calcification, and aortic atheroma) may all be a part of the spectrum of atherosclerosis.8 Later, Khoury and colleagues correlated the presence of aortic plaques and coronary artery disease.9

Boon and colleagues found an association of both mitral annular calcification and aortic valve calcification with age and vascular risk factors.10 Age, female sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hypercholesterolaemia were strongly associated with both mitral annular calcification and aortic valve calcification, with odd ratios varying between 2.2 and 2.8. Thus a significant association of mitral annular calcification with known major risk factors for coronary disease may partly explain the association of mitral annular calcification with significant obstructive coronary artery disease on angiography in our study.

Our angiographic findings on the extent and severity of obstructive coronary artery disease are similar to those reported by Adler and associates.11 Both studies show that mitral annular calcification is a marker and independent predictor of the presence of extensive coronary artery disease—that is, triple vessel disease or ≥ 50% left main coronary artery stenosis. However, the mean age of the patients in Adler’s study was 70 years, whereas the mean age of our patients was 57. The strong association of mitral annular calcification with obstructive coronary artery disease in this relatively young group of patients significantly increases the specificity of this condition as a marker of coronary artery disease. In contrast to our results, Nair and colleagues did not find a correlation between mitral annular calcification and coronary heart disease in patients younger than 60 years.12 However, the patients in Nair’s study did not undergo coronary angiography, and the diagnosis of coronary artery disease was based solely on clinical data.

Current evidence indicates that both coronary and aortic valvar calcification progress more rapidly in patients with a low density lipoprotein concentration above 130 g/l.13 It has been suggested that the cells responsible for valvar and vascular calcification are from the same precursor cells, and in vitro vascular and cardiac valvar calcification have several similarities. Nonetheless, whether mitral annular calcification is only a marker for the presence of significant coronary artery disease or is involved in the atherosclerotic process remains to be elucidated.14 It is, however, likely that calcific processes are part of the spectrum of arteriosclerosis. The strong association between mitral annular calcification and extensive coronary artery disease in our study and Adler’s11 suggests that this mitral valve pathology becomes more common when atherosclerosis is extensive and involves all three major epicardial coronary arteries.

Study limitations

Our study was done in patients who had both echocardiography and coronary angiography for various indications. This may have caused a bias in selecting patients with a high pre-test likelihood of having coronary artery disease. However, both groups were selected in the same way and were similarly affected by the selection bias, yet showed a highly significant difference in their angiographic findings. Nonetheless, our results are only preliminary and should be confirmed in population based studies.

Clinical implications

The finding of mitral annular calcification on echocardiography in patients under 65 years of age may be used as a marker for the presence of significant obstructive coronary artery disease. In symptomatic patients, this may support the need for an invasive evaluation of the patient’s complaints. In asymptomatic patients younger than 65, the finding of mitral annular calcification may warrant an aggressive modification of risk factors. The absence of mitral annular calcification in women under 65 appears to indicate a low probability of significant coronary artery disease. Whether mitral annular calcification is a useful marker for screening young patients for the presence of severe coronary artery disease needs to be determined in a large prospective study.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that in patients aged 65 years or less, mitral annular calcification is associated with an increased prevalence of severe and extensive obstructive coronary artery disease. In women, the absence of mitral annular calcification seems to infer a lower risk of obstructive coronary artery disease. Mitral annular calcification may be an easily detected echocardiographic marker of the presence of obstructive coronary artery disease, especially when associated with anginal symptoms.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the statistical support of Idit Lavi.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fulkerson PK, Beaver BM, Auseon JC, et al. Calcification of the mitral annulus: aetiology, clinical associations, complications and therapy. Am J Med 1979;66:967–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korn D, DeSanctis RW, Sell S. Massive calcification of the mitral annulus: a clinicopathological study of fourteen cases. N Engl J Med 1962;267:900–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savage DD, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP, et al. Prevalence of submitral (annular) calcium and its correlates in a general population-based sample (the Framingham study). Am J Cardiol 1983;51:1375–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nestico PF, Depace NL, Morganroth J, et al. Mitral annular calcification: clinical, pathophysiology, and echocardiographic review. Am Heart J 1984;107:989–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benjamin EJ, Plehn JF, D’Aagostino RB, et al. Mitral annular calcification and the risk of stroke in an elderly cohort. N Engl J Med 1992;327:374–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsumura Y, Takata J, Yabe T, et al. Atherosclerotic aortic plaque detected by transesophageal echocardiography: its significance and limitation as a marker of coronary artery disease in the elderly. Chest 1997;112:81–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adler Y, Zabarski RS, Vaturi M, et al. The association between mitral annulus calcium and aortic atheroma as detected by transesophageal echocardiographic study. Am J Cardiol 1998;81:784–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wexler L, Brundage B, Crouse J, et al. Coronary artery calcification: pathophysiology, epidemiology, imaging methods and clinical implications. A statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 1996;94:1175–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khoury Z, Gottlieb S, Stern S, et al. Frequency and distribution of aortic plaques in the thoracic aorta as determined by transesophageal echocardiography in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 1997;79:23–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boon A, Cheriex E, Lodder J, et al. Cardiac valve calcification: characteristics of patients with calcification of the mitral annulus or aortic valve. Heart 1997;78:472–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adler Y, Herz I, Vaturi M, et al. Mitral annular calcium detected by transthoracic echocardiography is a marker for high prevalence and severity of coronary artery disease in patients undergoing coronary angiography. Am J Cardiol 1998;82:1183–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nair CK, Sudhakaran C, Aronow WS, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients younger than 60 years with mitral annular calcium: comparison with age- and sex-matched control subjects. Am J Cardiol 1984;54:1286–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pohle K, Mäffert R, Ropers D, et al. Progression of aortic valve calcification: association with coronary atherosclerosis and cardiovascular risk factors. Circulation 2001;104:1927–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demer LL. Cholesterol in vascular and valvular calcification. Circulation 2001;104:1881–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]