Abstract

In the setting of acute myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiogenic shock in patients with significant unprotected left main coronary artery (LMCA) disease, treatment options are limited. In this report of a patient presenting in cardiogenic shock secondary to acute MI with critical LMCA stenosis, percutaneous coronary intervention with intra-aortic balloon pump support proved life saving.

Keywords: stenting, acute myocardial infarction, cardiogenic shock, stenosis, intra-aortic balloon pump

Cardiogenic shock in the setting of acute myocardial infarction (MI) carries a grave prognosis. Patients with acute left main coronary artery (LMCA) occlusion are particularly vulnerable to life threatening complications, as a large area of myocardium is put in jeopardy by such a lesion.

We report on a patient transferred to our centre in cardiogenic shock secondary to acute MI with critical LMCA stenosis. With little further scope for medical treatment, and with the patient being in a very high risk category for surgical revascularisation, percutaneous revascularisation and stenting with intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) support proved an effective life saving intervention.

CASE REPORT

A 66 year old female smoker with no known history of ischaemic heart disease presented to a local hospital with a three hour history of sudden onset, severe central chest pain radiating to the neck and left arm, and associated sweating, nausea, and dyspnoea. She could recall no prior chest pain or shortness of breath and had no other identifiable risk factors for ischaemic heart disease.

Aspirin 300 mg was given in the ambulance. On arrival the patient was clammy, tachycardic (pulse 105 beats/min), and hypotensive (blood pressure 93/66 mm Hg), with normal heart sounds and fine right basal inspiratory lung crepts. Initial ECG showed sinus tachycardia with left axis deviation, partial left bundle branch block, and T wave changes in leads I and aVL. Laboratory findings showed a creatine kinase concentration of 247 U/l, lactate dehydrogenase 310 U/l, and random total cholesterol 5.0 mmol/l. All other blood tests were normal. Non-ST elevation MI was diagnosed, confirmed by a cardiac enzyme series (peak creatine kinase concentration 1243 U/l at 12 hours).

Symptoms initially settled with glyceryl trinitrate and diamorphine 2.5 mg but recurred three hours later. A bolus of a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa platelet antagonist (tirofiban) and heparin was administered, followed by a continuous infusion of both drugs. The patient remained unstable with further chest pain and progressive dyspnoea. ECG progressed to show pronounced ST depression in leads I, aVL, II, III, aVF, and V3–V6 in the background of left bundle branch block. Echocardiography at 24 hours displayed anterior, septal, lateral, and inferior akinesia and severely impaired left ventricular function.

The patient was transferred to a tertiary cardiac centre for supportive management and possible intervention, with a diagnosis of cardiogenic shock secondary to presumed extensive left coronary artery territory infarct and pump failure. She arrived moribund, peripherally shut down, and oliguric, despite receiving large doses of intravenous diuretics and renal dose inotropes in the interim period. She was taken directly to the catheter suite where angiography with an intra-aortic balloon pump support showed a critically stenosed ostial left coronary artery lesion with diffuse left anterior descending artery disease, a mild right coronary artery proximal lesion, and normal circumflex artery (fig 1). The decision was made to stabilise her with IABP support overnight with a possible review by cardiothoracic surgical colleagues. A decision to proceed to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was taken, as the surgical option seemed rather unpragmatic with the patient’s background of a recent cardiac event and a medical history of severe disabling rheumatoid arthritis. Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty to the LMCA was performed under abciximab and heparin cover. A 6 French right femoral approach with a JL 3.5 SH guiding catheter and a BMW J guidewire was used. The lesion was crossed without much difficulty (fig 2). Incremental balloon sizes were used beginning from 2.5 to 4 mm. There was significant recoil following balloon inflations in the left main stem. Finally a 4.0 mm × 13 mm Zeta stent was deployed with a good post-stent angiographic result and TIMI (thrombolysis in myocardial infarction) grade III flow (fig 3). A single dose of clopidogrel 300 mg was administered along with once daily clopidogrel 75 mg, aspirin 150 mg, and simvastatin 20 mg.

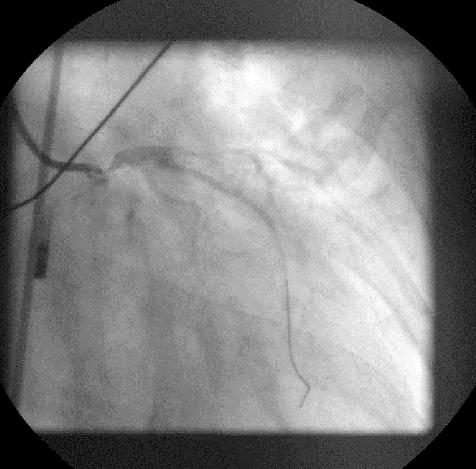

Figure 1.

Angiogram showing a critically stenosed ostial left coronary artery lesion with diffuse left anterior descending artery disease, a mild right coronary artery proximal lesion, and normal circumflex artery.

Figure 2.

Angiogram during balloon inflation in LMS.

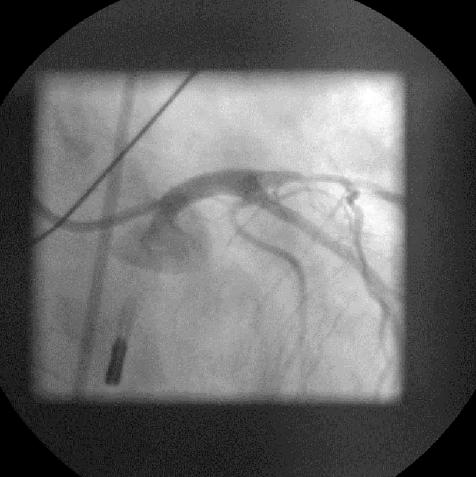

Figure 3.

Final angiographic result following stent implantation.

The patient was weaned off IABP support (day 3) and inotropes (day 6), achieving major improvement in respiratory status and a reasonable urine output with regular diuretics. Recovery was complicated by a chest infection. She tolerated low dose angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor with no deterioration in renal function. She was discharged in a stable state in New York Heart Association functional class II and with no symptoms of angina.

DISCUSSION

Significant LMCA stenosis carries a particularly sinister prognosis but occurs in only 2.5–10% of patients with coronary artery disease.1,2 With medical treatment alone, mortality is 21% at one year and 50% at three years.1,3–5

Unprotected LMCA stenosis (where none of the distal arteries are protected by a graft or good collaterals) poses specific management problems. The success of elective PCI in treating these lesions has been limited by potentially catastrophic complications including abrupt vessel closure and high restenosis rates.6,7 Before the introduction of coronary stents, balloon angioplasty of unprotected LMCA stenosis produced unacceptably high mortality rates.6,8 Although newer technologies have led to renewed interest in elective PCI, no randomised trials have yet compared it with surgery, which remains the ideal procedure.9

Acute LMCA occlusion leads to massive MI and a high incidence of cardiogenic shock, arrhythmias, and sudden death. The extensive area of compromised myocardium is reflected in the typical ECG pattern associated with LMCA obstruction, as observed in our patient. It has been suggested that ECGs can aid early identification of such patients, who should be prioritised for coronary angiography.10

At present relatively few patients with cardiogenic shock complicating acute MI undergo emergency PCI or surgery. Few hospitals have adequate facilities, and there has been conflicting evidence as to the value of early revascularisation. The SHOCK (should we emergently revascularize occluded coronaries for cardiogenic shock) trial11 randomly assigned such patients to emergency revascularisation (PCI 64%, coronary artery bypass grafting 36%) or intensive medical treatment. IABP support was given to 86% of both groups and 21% of the medically treated arm had delayed revascularisation procedures. There was no significant reduction in 30 day mortality with emergency revascularisation, but at six months it conferred a significant survival advantage. Analysis of the SHOCK trial registry12 showed lower in-hospital mortality rates in patients who underwent PCI than in those treated medically (46.4% v 78%), regardless of the timing of the procedure. Mortality was highest if LMCA was the culprit lesion,12 a finding supported by other groups.13 In one report of 16 patients with acute MI and unprotected LMCA stenosis who underwent PCI, technical success was achieved in 75% but only 31% survived to hospital discharge.9

In the high risk setting of acute MI and cardiogenic shock in patients with significant unprotected LMCA stenosis, treatment options are limited and revascularisation is difficult. Given the almost universally bleak outcome without intervention, PCI with IABP support may prove life saving.

Abbreviations

IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump

LMCA, left main coronary artery

PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention

SHOCK, should we emergently revascularize occluded coronaries for cardiogenic shock

TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction

REFERENCES

- 1.Cohen MV, Cohn PF, Herman MV, et al. Diagnosis and prognosis of main left coronary artery obstruction. Circulation 1972;45(suppl 1):57–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Proudfit WL, Shirey EK, Stones FM Jr. Distribution of arterial lesions demonstrated by selective cinecoronary arteriography. Circulation 1967;36:54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conley MJ, Ely RL, Kisslo J, et al. The prognostic spectrum of left main stenosis. Circulation 1978;57:947–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavine P, Kimbiris D, Segal BL, et al. Left main coronary artery disease: clinical, arteriographic and haemodynamic appraisal. Am J Cardiol 1972;30:791–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim JS, Proudfit WL, Sones FM. Left main coronary arterial obstruction: long term follow up of 141 non-surgical cases. Am J Cardiol 1975;36:131–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Keefe JH Jr, Hartzler GO, Rutherford BD, et al. Left main coronary angioplasty: Early and late results of 127 acute and elective procedures. Am J Cardiol 1989;64:144–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stertzer SH, Myler RK, Insel H, et al. Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty in left main coronary stenosis: a five year appraisal. Int J Cardiol 1985;9:149–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gruentzig AR, Senning A, Siegenthaler WE. Nonoperative dilatation of coronary-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 1979;301:61–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellis SG, Tamai H, Nobuyoshi M, et al. Contemporary percutaneous treatment of unprotected left main coronary stenosis: initial results from a multicenter registry analysis 1994–1996. Circulation 1997;96:3867–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorgels A, Vos MA, Mulleneers R, et al. Value of the electrocardiogram in diagnosing the number of severely narrowed coronary arteries in rest angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol 1993;72:999–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, Webb JG, et al. Early revascularization in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med 1999;341:625–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Webb JG, Sanborn TA, Sleeper LA, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention for cardiogenic shock in the SHOCK trial registry. Am Heart J 2001;141:964–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shihara M, Tsutsui H, Tsuchihashi M, et al. In-hospital and one-year outcomes for patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2002;90:932–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]