Abstract

Objective: To investigate whether a shorter health status instrument, the short form (SF)-12, is comparable with its longer version, the SF-36, for measuring health related quality of life of patients with coronary heart disease.

Design: Prospective cohort study with follow up at six and 12 months.

Setting: 18 cardiac rehabilitation centres in Germany.

Patients: Patients were enrolled at admission to the rehabilitation centres after myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass grafting, and percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty.

Analyses: Correlation coefficients were calculated between SF-12 and SF-36 physical component summary (PCS-12/-36) and mental component summary (MCS-12/-36) scores and the respective change scores. Responsiveness to change was determined with the standardised response mean.

Main results: 2441 patients were enrolled (78% men, mean (SD) age 60 (10) years; 22% women, 65 (10) years). Baseline PCS-12 and PCS-36 scores were highly correlated (r = 0.96, p < 0.001), as were baseline MCS-12 and MCS-36 scores (r = 0.96, p < 0.001). Similarly, change scores between baseline and 12 months were highly correlated (PCS-12/-36: r = 0.94, p < 0.001; MCS-12/-36: r = 0.95, p < 0.001). There was no difference in standardised response means between the SF-12 and SF-36 scales.

Conclusions: The SF-12 summary measures replicate well the SF-36 summary measures and show similar responsiveness to change. The SF-12 appears to be an efficient alternative to the SF-36 for the assessment of health related quality of life of patients with coronary heart disease.

Keywords: health related quality of life, SF-12, SF-36, coronary disease, responsiveness

The short form (SF)-36 questionnaire is one of the most widely used generic health status instruments to assess health related quality of life (HRQoL).1,2 It has been used extensively with cardiac patient populations, and some studies have investigated longitudinal changes in HRQoL.3–10 Dempster and Donnelly11 compared the validity, reliability, and sensitivity of the SF-36 with other generic questionnaires such as the Nottingham health profile and the sickness impact profile for patients with coronary heart disease. They came to the conclusion that the SF-36 is the most appropriate generic instrument to assess HRQoL of cardiac patient populations. However, the SF-36 contains 36 items and thus places a considerable burden on both patients and investigators.12

Ware and colleagues,13 therefore, decided to develop a substantially shorter questionnaire—the SF-12—reducing the number of items from 36 to 12. About 80% of adults tested in a pilot test completed the SF-12 in less than two minutes requiring only a third of the usual time for completion of the SF-36.14 Ware and colleagues13,14 tested the SF-12 in the general US population and in the medical outcomes study, an observational study of patients with chronic conditions such as hypertension, congestive heart failure, and recent myocardial infarction. They showed that the SF-12 summary measures were highly correlated with the SF-36 summary measures and that the SF-12 items explained about 90% of the variation of the SF-36 summary measures. Compared with the widespread use of the SF-36, however, few studies have used the SF-12 to assess HRQoL of patients with coronary heart disease and most have been cross sectional studies.13–17 The objective of the present study was, therefore, to compare the SF-12 with the SF-36 in a large longitudinal study of patients with coronary heart disease and, in particular, to compare the respective responsiveness to change in HRQoL.

METHODS

Design and patient population

The post infarction care study was a prospective multicentre study that examined HRQoL, coronary risk factors, medication, and clinical events after inpatient cardiac rehabilitation. Details of the study design and results in regard to clinical events and risk factors have been published.18 Briefly, study patients were consecutively enrolled at admission to one of the 18 participating rehabilitation centres. Inclusion criteria were myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), and percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) as the primary indication for admission. Exclusion criteria were refusal by the patient, language or intellectual barriers, and medical conditions leading to direct readmission to acute care. In Germany, patients usually stay for about three weeks in inpatient cardiac rehabilitation. Follow up questionnaires were sent to the patients by mail six and 12 months after discharge from the rehabilitation centre. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of Charité University Medical Center. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

SF-36 and SF-12 questionnaires

The SF-36 is a generic health status instrument with 36 items, eight subscales that aggregate 2–10 items each, and two summary measures that aggregate the subscales.1,2 The two summary measures of the SF-36 will be referred to as physical component summary 36 (PCS-36) and mental component summary 36 (MCS-36) scales. Compared with the SF-36, the SF-12 has only one or two items from each of the eight health concepts of the SF-36.13 The SF-12 items allow the calculation of the PCS (PCS-12) and MCS (MCS-12) scales but not of the subscales. The items selected for the SF-12 and the scoring algorithms for the summary measures were cross validated in nine countries.19 The German version of the SF-12 was translated and validated according to the methods developed by the International Quality of Life Assessment Group.20 We calculated the SF-12 scores from items embedded in the SF-36, which has been shown to be equivalent to calculating the SF-12 scores from the stand alone SF-12 items.13,21 As SF-12 items are relatively heterogeneous, internal consistency estimates of reliability underestimate the reliability of SF-12 measures and are not applicable to single item measures.13 Higher SF-12 and SF-36 scores indicate better HRQoL, a positive change in SF-12 and SF-36 scores indicates improvement in HRQoL, and a negative change indicates deterioration.

For the calculation of the SF-36 scales, missing data were imputed according to the recommendations of the SF-36 user’s manual.1 In the recommended algorithm, a person specific estimate for any missing item is substituted when the respondent answered at least 50% of the items of a subscale. The summary scales are then calculated from the subscales and are set as missing if the respondent is missing any one of the eight SF-36 subscales. The SF-12 summary scales, on the other hand, are calculated directly from the 12 items. It is recommended that the SF-12 summary scales be set as missing if the respondent is missing any one of the SF-12 items in the survey.13

Responsiveness to change

Responsiveness to change was compared between the SF-12 and the SF-36. Indices of responsiveness are the responsiveness statistic, effect sizes, relative efficiency, and the standardised response mean (SRM).22 There is no consensus on which is the most appropriate index. We chose the SRM, as it is one of the most commonly used indices of responsiveness and takes the variation of change into account.23–26 The SRM is calculated by dividing the mean change in scores by the standard deviation of the change. It can be easily interpreted by Cohen’s interpretation of effect sizes with SRMs of at least 0.2 being regarded as small, SRMs of at least 0.5 as moderate, and SRMs of 0.8 or greater as large.27

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the PCS-12 and MCS-12 scores and for the PCS-36 and MCS-36 scores at baseline and during follow up. The correlation between baseline PCS-12/-36 and MCS-12/-36 scores and the correlation between PCS-12/-36 and MCS-12/-36 change (12 months – baseline) scores were estimated by the Pearson correlation coefficient. Responsiveness to change was analysed as described above. Linear regression analysis was used to determine how much of the variation in PCS-36 and MCS-36 scores is explained by the respective PCS-12 and MCS-12 scores. The models were adjusted for age and sex. To test whether there was any significant effect modification by age or sex, the interaction terms PCS-12/MCS-12*age and PCS-12/MCS-12*sex were used. All tests for significance were two sided; the significance level was α = 0.05. Statistical analyses were done with SPSS version 10.0 for windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

RESULTS

Study population

A total of 2441 patients were enrolled between January and July 1997. Of all study patients, 78% (n = 1907) were men, with a mean (SD) age of 60 (10) years, and 22% women (n = 534), with a mean (SD) age of 65 (10) years. Primary indications for admission were myocardial infarction (56%, n = 1379), CABG (38%, n = 916), and PTCA (6%, n = 141). The response rates of patients to the questionnaires were 92% (n = 2233) after six months and 85% (n = 2069) after 12 months.

Baseline SF-12 and SF-36 summary scores

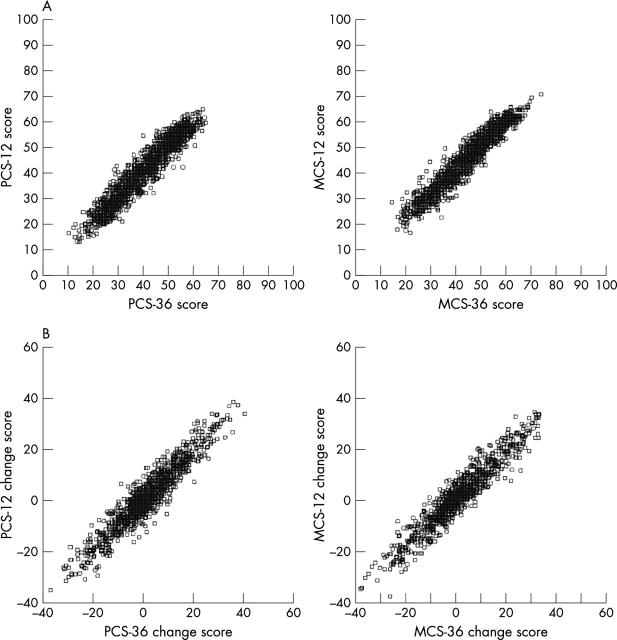

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the PCS and MCS scales of the SF-12 and SF-36. Normative data of a disease specific US population are given for comparison. Means and standard deviations of the SF-12 and SF-36 summary scores at baseline were similar. Strong correlations existed between baseline PCS-12 and PCS-36 (r = 0.96; p < 0.001) and between baseline MCS-12 and MCS-36 (r = 0.96; p < 0.001) (fig 1A).

Table 1.

Baseline scores of the SF-12 and SF-36 summary measures

| PCS-12 | PCS-36 | MCS-12 | MCS-36 | |

| Mean (SD) | 40 (12) | 41 (12) | 47 (11) | 46 (12) |

| Range | 12–63 | 10–66 | 16–71 | 10–74 |

| Missing | 27% | 25% | 27% | 25% |

| Mean disease specific US norm population* | 42 | 43 | 52 | 52 |

Figure 1.

Correlation between SF-12 and SF-36 summary scores. (A) Correlation between baseline physical component summary 12 (PCS-12) and PCS-36 scores and baseline mental component summary 12 (MCS-12) and MCS-36 scores. (B) Correlation between PCS-12 and PCS-36 change scores and between MCS-12 and MCS-36 change scores (12 months – baseline).

Variation in SF-36 scores

About 92% of the variation in PCS-36 scores at baseline was explained by the model (table 2). There was no significant interaction between the PCS-12 scores and either age or sex. About 93% of the variation in MCS-36 scores at baseline was explained by the model (table 2). There was no significant interaction between the MCS-12 scores and either age or sex.

Table 2.

Variation in SF-36 summary scales scores at baseline

| Regression coefficient | 95% confidence interval | p Value | |

| PCS-36 scale† | |||

| PCS-12 | 0.938 | 0.833 to 1.043 | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.276 | −1.403 to 1.956 | 0.747 |

| Age | −0.049 | −0.133 to 0.033 | 0.240 |

| PCS-12*age | 0.001 | −0.001 to 0.002 | 0.553 |

| PCS-12*sex | −0.009 | −0.051 to 0.034 | 0.698 |

| MCS-36 scale‡ | |||

| MCS-12 | 0.948 | 0.851 to 1.046 | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.606 | −1.157 to 2.369 | 0.500 |

| Age | −0.032 | −0.115 to 0.052 | 0.459 |

| MCS-12*age | 0.001 | −0.001 to 0.003 | 0.257 |

| MCS-12*sex | −0.008 | −0.047 to 0.031 | 0.701 |

†R2 = 0.92; ‡R2 = 0.93.

Change and responsiveness to change

PCS-12 and PCS-36 change scores (12 months – baseline) were strongly correlated (r = 0.94; p < 0.001) (fig 1B). Similarly, MCS-12 and MCS-36 change scores were strongly correlated (r = 0.95; p < 0.001). Table 3 shows mean SF-12 and SF-36 summary scores at baseline, six months, and 12 months for patients with complete follow up data, as well as the respective change scores (12 months – baseline).

Table 3.

PCS and MCS scores of the SF-12 and SF-36 at baseline and during follow up according to indication*

| Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | Change† | SRM | |

| Myocardial infarction | |||||

| PCS-12 (n = 637) | 46 (10) | 43 (10) | 44 (10) | −1.9 (11) | −0.18 |

| PCS-36 (n = 673) | 46 (10) | 44 (11) | 45 (10) | −1.7 (11) | −0.15 |

| MCS-12 (n = 637) | 50 (11) | 49 (11) | 49 (11) | −0.5 (11) | −0.05 |

| MCS-36 (n = 673) | 49 (11) | 48 (11) | 48 (11) | −0.5 (11) | −0.04 |

| CABG | |||||

| PCS-12 (n = 391) | 35 (11) | 42 (10) | 43 (10) | 7.7 (12) | 0.63 |

| PCS-36 (n = 412) | 36 (11) | 42 (10) | 43 (11) | 7.3 (12) | 0.60 |

| MCS-12 (n = 391) | 46 (12) | 51 (10) | 51 (10) | 4.8 (13) | 0.37 |

| MCS-36 (n = 412) | 45 (12) | 50 (11) | 50 (11) | 4.3 (13) | 0.33 |

| PTCA | |||||

| PCS-12 (n = 64) | 35 (11) | 39 (10) | 39 (11) | 4.6 (10) | 0.48 |

| PCS-36 (n = 69) | 36 (11) | 40 (10) | 41 (11) | 4.2 (9) | 0.47 |

| MCS-12 (n = 64) | 44 (11) | 47 (11) | 48 (10) | 3.5 (12) | 0.29 |

| MCS-36 (n = 69) | 43 (12) | 46 (11) | 46 (11) | 2.9 (12) | 0.25 |

Data are mean (SD).

*Numbers refer to patients with complete data at baseline and follow up; †change between 12 months and baseline. Values may not add up due to rounding.

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; SRM, standardised response mean.

Responsiveness to change as measured by the SRM was greatest in the PCS-12 and PCS-36 scales of patients after CABG and PTCA followed by the respective MCS-12 and MCS-36 scales (table 3). SRMs were smallest for change after myocardial infarction. Overall, SRMs were similar for PCS-12 and PCS-36 scales, as well as for MCS-12 and MCS-36 scales.

Missing values

The percentage of missing values for the calculation of PCS and MCS scores was 25% (n = 599) for the SF-36 summary scales and 27% (n = 667) for the SF-12 summary scales (table 1). There were no differences between patients with missing SF-12 and those with missing SF-36 values regarding socioeconomic variables such as age (62 (10) v 63 (10) years), sex (both 72% men) and education (both 10% > 10 years), nor in the result of the exercise ECG (87 (32) v 86 (32) W). Table 4 shows the percentage of missing values for the 12 items used to score the SF-12 summary scales. Missing values were highest for the items belonging to the role-physical and role-emotional health concepts.

Table 4.

Missing values for items of the SF-12

| Item* | Number missing |

| In general, would you say your health is... | 20 (0.8%) |

| Moderate activities | 181 (7.4%) |

| Climbing several flights of stairs | 126 ((5.2%) |

| Accomplished less than you would like (physical) | 310 (12.7%) |

| Limited in the kind of activities (physical) | 376 (15.4%) |

| Pain interferes with normal work | 56 (2.3%) |

| Have a lot of energy | 253 (10.4%) |

| Health interferes with social activities | 56 (2.3%) |

| Accomplished less than you would like (emotional) | 285 (11.7%) |

| Didn’t do activities as carefully as usual (emotional) | 371 (15.2%) |

| Felt calm and peaceful | 207 (8.5%) |

| Felt downhearted and blue | 233 (9.5%) |

*Abbreviated description of items.13

DISCUSSION

The SF-12 summary scores were highly correlated with the SF-36 summary scores for patients with coronary heart disease in our study. High correlations between the SF-12 and the SF-36 have been described for both general populations and for patients with certain diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and stroke.13,19,24,28,29 For patients with coronary heart disease, high correlations between the SF-12 and SF-36 summary measures (r > 0.9) were described in a small subsample of the medical outcomes study of patients after recent myocardial infarction.13 Our analyses confirm the findings of the medical outcomes study in a larger sample of patients with coronary heart disease.

In our study, responsiveness to change of the SF-12 and SF-36 summary measures was similar in patients with coronary heart disease. Other studies of patients with different conditions such as congestive heart failure, sleep apnoea, inguinal hernia, and low back pain also reported a similar responsiveness to change of the SF-12 and SF-36 summary scales.26,29,30 A slightly lower responsiveness to change of the SF-12 compared with the SF-36 summary measures was reported for patients with rheumatoid arthritis and epilepsy.24,25 For patients with coronary heart disease, responsiveness to change of the SF-12 and SF-36 summary measures has not been compared. One small longitudinal study investigated responsiveness to change of the SF-12 summary measures for patients after myocardial infarction.23 The authors reported large to moderate SRMs for the physical SF-12 summary measure during the first six weeks and small SRMs for the mental SF-12 summary measure during the total 24 week follow up period.

The SF-12 summary measures replicate the SF-36 summary measures well. However, a criticism of the SF-12 is that it allows only the calculation of the summary scales but not of the subscales. The summary scales may conceal important information contained in the subscales of the SF-36.23,30 Here, investigators have to trade off between the additional information of the subscales and longer questionnaires or interviews. In clinical trials, for example, the effect of a treatment and the difference between the intervention and control groups may be assessed sufficiently by the physical and mental summary measures. It is, therefore, at the investigators’ discretion to decide whether the use of the summary measures is appropriate for their respective study design.

A cause for concern are the high percentages of missing values in both the SF-12 and the SF-36 summary measures. The Australian study validating the SF-12 in a heart and stroke population reported a similar percentage of missing values (22%) to that in our study.17 Patients who did not complete the questionnaire were more likely to be female, older, and less educated and to have stayed longer in hospital and been admitted to emergency.17 Missing rates for the SF-12 summary measures—if reported—of other studies have been between 10–20%.15,16 The high percentage of missing values is, however, not a problem specific to the SF-12 summary measures but also to the SF-36 summary measures. Despite different scoring algorithms and the imputation of missing data for the SF-36 subscales, missing rates were similar for the SF-12 and SF-36 summary scales in our study. An explanation is that the imputation of missing data is not possible for certain subscales if more than 50% of the items are missing. Missing rates in our study were highest for items of the health concepts role-physical and role-emotional, which has been reported elsewhere as well.31–34 It seems that some items prevent both direct calculation of the SF-12 summary scales and calculation of the SF-36 subscales and subsequently of the SF-36 summary scales. However, missing rates in our study should be interpreted with care, since we used SF-12 items embedded in the much longer SF-36 questionnaire. Missing rates might have been different if the SF-12 items had been administered alone (unembedded). Also, a “context effect” of the embedded form with the remaining 24 items of the SF-36 causing responses to the SF-12 items to be different cannot be excluded. Ware and colleagues13 compared the mean scores of SF-12 items embedded in the SF-36 in a sample of 525 employees with the mean scores of the SF-12 items unembedded in the same sample a year later. They found a very high (r = 0.999) product–moment correlation between embedded and unembedded SF-12 item means. We therefore assume that the results of the present study are not compromised by the use of the embedded SF-12 items.

Conclusion

The SF-12 appears adequate in replacing the SF-36 in large studies assessing HRQoL of patients with coronary heart disease. The use of the SF-12 may reduce respondent burden and save resources.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by a grant from MSD Sharp and Dohme GmbH, Germany. It was conducted in cooperation with the German Society for Prevention and Rehabilitation and the German Society for Cardiology.

Abbreviations

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting

HRQoL, health related quality of life

MCS, mental component summary

PCS, physical component summary

PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty

SF, short form

SRM, standardised response mean

REFERENCES

- 1.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, et al. SF-36 health survey. Manual and interpretation guide. Boston: New England Medical Center, The Health Institute, 1993.

- 2.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 physical and mental summary scales: a user’s manual. Boston: New England Medical Center, The Health Institute, 1994.

- 3.Rumsfeld JS, MaWhinney S, McCarthy M, et al. Health-related quality of life as a predictor of mortality following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. JAMA 1999;281:1298–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosworth HB, Siegler IC, Olsen MK, et al. Social support and quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease. Qual Life Res 2000;9:829–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown N, Melville M, Gray D, et al. Quality of life four years after acute myocardial infarction: short form 36 scores compared with a normal population. Heart 1999;81:352–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jette DU, Downing J. Health status of individuals entering a cardiac rehabilitation program as measured by the medical outcomes study 36-item short-form survey (SF-36). Phys Ther 1994;74:521–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krumholz HM, McHorney CA, Clark L, et al. Changes in health after elective percutaneous coronary revascularization: a comparison of generic and specific measures. Med Care 1996;34:754–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Covinsky KE, Chren MM, Harper DL, et al. Differences in patient-reported processes and outcomes between men and women with myocardial infarction. J Gen Intern Med 2000;15:169–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lalonde L, Clarke AE, Joseph L, et al. Health-related quality of life with coronary heart disease prevention and disease. J Clin Epidemiol 2001;54:1011–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bengtsson I, Hagman M, Wedel H. Age and angina as predictors of quality of life after myocardial infarction. Scand Cardiovasc J 2001;35:252–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dempster M, Donnelly M. Measuring the health related quality of life of people with ischaemic heart disease. Heart 2000;83:614–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iglesias C, Torgerson D. Does length of questionnaire matter? A randomised trial of response rates to a mailed questionnaire. J Health Serv Res Policy 2000;5:219–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-12: how to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales, 3rd edn. Lincoln: QualityMetric Incorporated, 1998.

- 14.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey. Med Care 1996;34:220–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Consoli SM, Guize L, Ducimetière P, et al. Characteristics and predictive value of quality of life in a French cohort of patients suffering from angina pectoris. Arch Mal Coeur 2001;94:1357–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crilley JG, Farrer M. Impact of first myocardial infarction on self-perceived health status. Q J Med 2001;94:13–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim LLY, Fisher JD. Use of the 12-item short-form (SF-12) health survey in an Australian heart and stroke population. Qual Life Res 1999;8:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willich SN, Müller-Nordhorn J, Kulig M, et al. Cardiac risk factors, medication, and recurrent clinical events after acute coronary disease: a prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J 2001;22:307–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 health survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA project. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1171–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bullinger M, Kirchberger I. Der SF-36 Fragebogen zum Gesundheitszustand. Handbuch für die deutschsprachige Fragebogenversion. Göttingen: Hogrefe Verlag für Psychologie, 1998.

- 21.Scholfield MJ, Mishra G. Validity of the SF-12 compared with the SF-36 health survey in pilot studies of the Australian longitudinal study on women’s health. J Health Psychol 1998;3:259–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright JG, Young NL. A comparison of different indices of responsiveness. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:239–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubenach S, Shadbolt B, McCallum J, et al. Assessing health-related quality of life following myocardial infarction: Is the SF-12 useful? J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:306–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hurst NP, Ruta DA, Kind P. Comparison of the MOS short form-12 (SF12) health status questionnaire with the SF36 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 1998;37:862–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birbeck GL, Kim S, Hays RD, et al. Quality of life measures in epilepsy: how well can they detect change over time? Neurology 2000;54:1822–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bessette L, Sangha O, Kuntz KM, et al. Comparative responsiveness of generic versus disease-specific and weighted versus unweighted health status measures in carpal tunnel syndrome. Med Care 1998;36:491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988.

- 28.Pickard AS, Johnson JA, Penn A, et al. Replicability of SF-36 summary scores by the SF-12 in stroke patients. Stroke 1999;30:1213–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riddle DL, Lee KT, Stratford PW. Use of the SF-36 and SF-12 health status measures. Med Care 2001;39:867–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jenkinson C, Layte R, Jenkinson D, et al. A shorter form health survey: can the SF-12 replicate results from the SF-36 in longitudinal studies. J Public Health Med 1997;19:179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mallinson S. The short-form 36 and older people: some problems encountered when using postal administration. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52:324–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayes V, Morris J, Wolfe C, et al. The SF-36 health survey questionnaire: is it suitable for use with older adults? Age Ageing 1995;24:120–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andresen EM, Bowley N, Rothenberg BM, et al. Test-retest performance of a mailed version of the medical outcomes study 36-item short-form health survey among older adults. Med Care 1996;34:1165–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loge JH, Kaasa S, Hjermstad MJ, et al. Translation and performance of the Norwegian SF-36 health survey in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. I. Data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability, and construct validity. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1069–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]