Abstract

The British Cardiac Society commissioned this report to help address inconsistencies in the terminology for acute coronary syndromes and wide variations in the threshold for the diagnosis of myocardial infarction (MI) depending on the assay performed, the precision, and the sensitivity. In addition, several publications have highlighted potential problems with the application of the European Society of Cardiology(ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC) consensus document published in 2000. A revision process has been initiated under the guidance of the ESC, the ACC, and the American Heart Association (AHA). The purpose of this report is to help inform the next revision of the ESC/ACC/AHA guidelines for the diagnosis of MI.

Keywords: creatine kinase, ST elevation myocardial infarction, myocardial infarction, non-ST myocardial infarction, troponin

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) describes a spectrum of clinical manifestations that result from a common pathophysiological process. After rupture or erosion of an atheromatous coronary plaque, intraluminal thrombosis partially or completely obstructs the coronary artery. The process is complicated by encroachment of the disrupted coronary plaque into the vessel lumen, by embolisation of fragments of thrombus into the distal coronary circulation, and by changes in vascular tone.

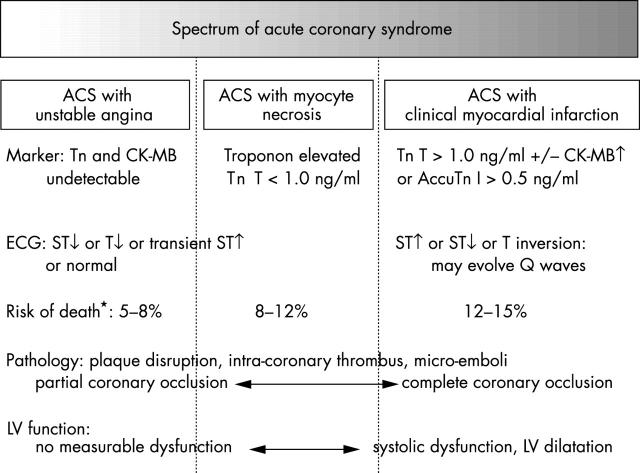

The clinical manifestations depend on the volume of myocardium affected and by the severity of ischaemia or myocardial necrosis. Thus, the spectrum ranges from unstable angina with ischaemia, but without detectable myocyte necrosis, to ACS with variable degrees of myocyte necrosis. The latter encompasses patients with a typical clinical syndrome accompanied by ECG changes and increased cardiac markers (troponins or creatine kinase (CK) MB) through to those with extensive infarction complicated by haemodynamic compromise and other major complications (fig 1).

Figure 1.

Spectrum of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). CK, creatine kinase; LV, left ventricular; Tn, troponin. *Risk of death is from hospitalisation to six months.

Patients with erosion or rupture of an atheromatous coronary plaque may or may not go on to develop myocardial infarction (MI). Whether detectable infarction occurs depends on several pathophysiological features such as the extent and locus of plaque rupture, the nature of thrombotic consequences, the presence of collateral vessels, and the effectiveness and timing of reperfusion. MI confers particular risks as a result of impairment of left ventricular function and mechanical and arrhythmic complications. The label MI has important implications for a patient’s occupation, disability claims, and insurance. Thus, an accurate and consistent diagnosis of infarction is critically important to guide patient management and to provide robust reference data in epidemiological studies, clinical trials, and the coding of disease definitions (International classification of diseases, Read, SNOMED). An international group, led by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), American College of Cardiology (ACC), and American Heart Association (AHA), are further revising the proposals published in 2000 for the definition of MI. The input from the British Cardiac Society (BCS) Working Group will help to inform the revision.

The remit of the British Cardiac Society Working Group on MI is:

To establish a nomenclature for acute coronary syndromes to meet current treatment and prognostic needs of patients

To recommend a diagnostic threshold to distinguish patients with MI from patients with acute coronary syndromes with minor but prognostically important increases of troponin concentrations

To recommend a strategy for establishing a reference standard for troponin assays.

World Health Organization definition of MI

Traditionally, MI has been diagnosed according to the 1971 World Health Organization (WHO) criteria (table 1) based on the clinical syndrome, ECG changes, and increase of relatively non-specific markers of myocardial damage such as CK. The commonly accepted diagnostic threshold of a twofold increase in CK above the laboratory upper limit was not based on the absence of histological evidence of infarction below this arbitrary threshold but on the limited diagnostic accuracy of the assay (wide interindividual and intraindividual variation due the effects of physical activity, ethnicity, and other factors).

Table 1.

Criteria of the World Health Organization and the Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology

| World Health Organization criteria for MI |

Definite acute MI

|

| Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology criteria |

Criteria for acute, evolving, or recent MI—one of the following:

|

Criteria for established MI—any of the following:

|

MI, myocardial infarction.

ESC/ACC redefinition of MI

In 2000, a joint ESC/ACC committee published a redefinition of MI1 (table 1) based on more sensitive and specific markers of myocyte necrosis (troponins or CK-MB mass). The consequence is that a substantially increased proportion of patients with ACS will be classified as having had an MI by the new ESC/ACC definition compared with the WHO criteria. Both sets of criteria include ST elevation and non-ST elevation MIs.

Prognosis in ACS and the need for consistent definitions in ACS

Clinical trials and large scale registry programmes have shown that the outcome for non-ST elevation MI is not benign (12–13% death rate at six months in GRACE (global registry of acute coronary events) and PRAIS-UK (prospective registry of acute ischaemic syndromes in the UK)) and is similar to the six month survival of patients with ST elevation MI who reach hospital alive.2,3 However, the time course and nature of the cardiac consequences differ substantially.

Furthermore, patients with non-ST elevation MI at higher risk may benefit particularly from acute interventional strategies and certain pharmacological treatment (glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, low molecular weight heparin) compared with patients with ACS who do not have increased markers or other features of higher risk. Patients with a clinical syndrome of ACS and an abnormal ECG but no marker increase (“unstable angina”) do not have a benign prognosis when the diagnosis is supported by evidence of underlying ischaemic heart disease (5% death at six months).2,3 Thus, more accurate delineation of risk by sensitive cardiac markers is to be welcomed. However, the inclusion within the classification “myocardial infarction” of patients with a lesser volume of myocardial damage than was previously detectable will affect comparisons with previous reference studies and epidemiological cohorts.4 For example, the impact of a lesser proportion of patients with MI with Q wave infarctions will need to be defined in longitudinal studies. Larger infarctions are particularly susceptible to the long term hazards of ventricular remodelling and heart failure. This has important implications for patients who may unjustifiably be given prognostic information based on historical comparisons, are barred from certain occupations, and are inappropriately penalised or rewarded by financial and insurance institutions. Ongoing epidemiological studies will need also to take account of the new threshold for diagnosis of MI.

The advent of more sensitive assays of myocyte necrosis has given rise to a confusion of terminology to describe patients with ACS with a troponin increase but no ST elevation or bundle branch block: “non-ST elevation MI”, “troponin positive ACS”, “minor myocardial damage”, “prognostically important unstable angina”, “necrosette”, or even “troponitis”. Clarification and consistency of terminology are required.

Stratification of risk in ACS

Binary approaches to stratifying risk in patients with ACS lack sufficient precision: simply separating patients into troponin positive or negative groups as the sole method of determining higher or lower risk is insufficiently sensitive.

Troponin increase should be regarded as only one of the independent predictors of risk in patients with ACS.

More reliable and extensively tested predictors include the TIMI (thrombolysis in myocardial infarction) risk score (table 2)5 and the GRACE risk score (table 3).6

Table 2.

Components of the TIMI (thrombolysis in myocardial infarction) risk score

|

Each characteristic qualifies for one point in the risk score.

Data from Antman et al.5

Table 3.

GRACE (global registry of acute coronary events) risk score: independent predictors of death among patients presenting with the spectrum of ACS based on widely available clinical and biological markers

|

Each characteristic is included in the nomogram (or PDA programme) and a numerical risk of death (or death/MI) is provided.

C index for death 0.84 (Granger et al,6www.outcomes.org/grace).

CK, creatine kinase.

The GRACE risk model was derived from 12 500 patients across the spectrum of ACS and validated externally. It accurately predicts death (or death/MI) in hospital and at six months.6 The TIMI and GRACE risk scores show that a marker increase is only one of several multivariate predictors of adverse outcomes.

More robust risk prediction requires the integration of all of the key risk predictors.

Variations in diagnostic accuracy of assay systems

An important issue to be considered in the ESC/ACC diagnosis of MI concerns the differences in sensitivity and diagnostic accuracy between troponin assays. Thus, in two laboratories in the same city (or even the same institution when “point of care” and laboratory assays are both used) a patient’s condition may satisfy the diagnosis of MI in one assay system but not the other. The more sensitive and precise the assay system, the larger the proportion of patents who will fulfil the ESC/ACC definition of MI.7 A robust reference standard for troponin assays and a defined and consistent threshold and nomenclature for those with marker increases are needed. Experimental studies of coronary artery occlusion show that troponin concentrations 96 hours after occlusion accurately reflect infarct size (p = 0.001, r = 0.74).8

PROPOSED NOMENCLATURE FOR ACS

While recognising the common pathophysiological mechanisms across the spectrum of ACS, we determine the clinical and cardiac marker manifestations by the volume of myocardium affected and the severity of ischaemia. Despite the similarities in disease mechanism the time course and severity of cardiac complications vary substantially across the spectrum of ACS. Similarly, treatment patterns differ.

The Working Group proposes that the spectrum of ACS should be subdivided as follows:

ACS with unstable angina

ACS with myocyte necrosis

ACS with clinical MI.

The Working Group recommends that the term “unstable angina” should be reserved for patients with a clinical syndrome, but with undetectable troponin or CK-MB markers. Unstable angina requires supporting evidence of coronary disease (abnormal ECG or prior documented coronary disease).

The term “clinical myocardial infarction” should be reserved for patients in the context of a typical clinical syndrome and a marker increase above the diagnostic threshold. The Working Group proposes that the threshold for defining clinical MI be set at 1.0 ng/ml for troponin T or 0.5 ng/ml for AccuTnI (or equivalent threshold with other troponin I methods). This recommendation is made on the basis that the risk of death is similar to that seen with CK increase of 400 U/l (troponin T) and comparison with WHO definitions (AccuTnI troponin I, see below). The extent of left ventricular dysfunction is also similar to that seen with a CK increase of ⩾ 400 U/l (C Knight and A Timmis, personal communication). A troponin T increase > 2.8 ng/ml predicts a left ventricular ejection fraction of < 40% after MI (sensitivity 100%, confidence interval 84.6 to 100).14 The specificity is 92.9% (confidence interval 76.5 to 89.1). These finding were irrespective of whether or not thrombolysis was used.

An analysis has been performed of 804 patients admitted with ACS with both troponin T and CK results (A Timmis et al, personal communication, 2004). Patients classified as having had an MI according to traditional criteria (CK > 400 U/l) had an inpatient mortality of 8.4% with a combined incidence of death and left ventricular failure of 27.2%. Risk stratification of the entire cohort of patients according to the troponin T concentration showed a gradient of risk ranging from an inpatient mortality of 1.8% for patients with a normal troponin to 8% for patients with a troponin concentration in the highest tertile (⩾ 1.1 ng/ml). As table 4 shows, in this group a troponin concentration ⩾ 1.1 ng/ml approximates to the traditional definition of MI in terms of in-hospital outcome.

Table 4.

Complication rates by cardiac troponin tertile

| Cardiac troponin T (ng/ml) | CK >400 U/l | ||||

| ⩽0.01 (n = 338) | Tertile 1: ⩽0.26 (n = 159) | Tertile 2: ⩽1.1 (n = 156) | Tertile 3: ⩾1.1 (n = 151) | ||

| LVF | 33 (9.9%) | 24 (15.1%) | 29 (18.6%) | 6 (23.8%) | 61 (24.5%) |

| Death | 6 (1.8%) | 2 (1.3%) | 6 (3.9%) | 12 (8%) | 21 (8.4%) |

| Death/LVF | 36 (10.7%) | 24 (15.1%) | 30 (19.2%) | 41 (27.2%) | 68 (27.2%) |

For the upper tertile of cardiac troponin T the risk of left ventricular failure (LVF), death, and combined death/LVF was significantly greater than in all the other groups.

All p<0.003.

The decision value for AccuTnI is based on a multicentre study of 328 patients, of whom 74 had AMI defined by WHO criteria. The use of troponin I > 0.5 ng/ml gave optimal sensitivity (96%) and specificity (94%) (R Rossington, Beckman Coulter, personal communication, 2003).

The term “ACS with myocyte necrosis” should be reserved for patients with a typical clinical syndrome plus an increased troponin concentration below the diagnostic threshold (that is, troponin T < 1.0 ng/ml or AccuTnI < 0.5 ng/ml). It is recognised that such patients have an adverse prognosis including increased risk of death compared with patients with unstable angina without an increased marker. Nevertheless, the distribution of their subsequent coronary events differs from that of patients with a clinical MI: the events continue over time resulting in further hospitalisation and infarction, whereas after clinical MI there is a clustering of events around the initial presentation including risk of death, ventricular arrhythmias, and heart failure.

The Working Group recommends that in the context of a typical ACS clinical myocardial infarction should be diagnosed when the maximum troponin T increase is > 1.0 ng/ml or AccuTnI > 0.5 ng/ml (and/or new Q waves develop on the ECG). Individual laboratories that use other troponin I assays will need to estimate an equivalent troponin I concentration.

The Working Group recommends that patients with an ACS and myocyte necrosis as evident by detectable troponin (that is, troponin T < 1.0 ng/ml or AccuTnI < 0.05 ng/ml) should be deemed to have ACS with myocyte necrosis.

A REFERENCE STANDARD FOR TROPONIN ASSAYS

There are insufficient data to compare measurements accurately between troponin assays. It is anticipated that this will change when a robust reference standard for the troponin assays is prepared. The International Federation for Clinical Chemistry is addressing this issue and hopes to report reference standards for troponins in 2004. The Working Group recommends that the BCS adopt this international reference standard when it becomes available.

TROPONIN INCREASE IN PATIENTS WITHOUT ACS

False positive results

False positive results may be found when the true troponin concentration lies close to the diagnostic threshold, but the assay lacks sufficient precision. If the assay precision is poor (that is, the coefficient of variation is large), then by the play of chance a number of true negative results will appear “positive” and vice versa.

This problem may be resolved by using later generations of troponin assays with sufficient precision at the decision making points (that is, < 10% coefficient of variation at the 99th centile upper limit for normal). This will ensure greater confidence in the diagnostic threshold, which will be well separated from the upper limit for normal.8–12 Many of the earlier generation assays do not meet this level of predictive accuracy yet may still be used in current practice (A Reid SEQAS, personal communication, 2003).

The Working Group recommends that all British hospital laboratories should review their troponin assays to ensure that they meet the ESC/ACC recommendations for precision.

Other causes of myocyte necrosis

Patients with pulmonary embolism, myocarditis, or heart failure may have increased troponin concentrations but without other features of ACS. Nevertheless, studies have shown that the extent of myocyte necrosis in such patients predicts adverse outcome. In patients with renal insufficiency increased troponins are also associated with adverse outcome but the mechanisms are complex and include altered clearance of troponins.

A variety of conditions cause myocyte necrosis and this may be reflected accurately by troponin increase, despite the fact that such patients have not experienced an ACS.

DIAGNOSIS OF MI WITH NUCLEAR IMAGING TECHNIQUES

Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) myocardial perfusion imaging is an established procedure for the diagnosis for infarction but has relatively limited spatial resolution of about 10 × 10 × 10 mm (full width half maximum resolution). In contrast, cardiac magnetic resonance with late gadolinium enhancement is more sensitive than SPECT, especially for the detection of smaller subendocardial infarctions representing 1–10% of left ventricular volume.12–14 The spatial resolution of cardiac magnetic resonance is about 60-fold greater than SPECT (1.4 × 1.9 × 6.0 mm). Nevertheless, neither of these imaging techniques can distinguish recent from prior infarction.

TROPONIN INCREASES IN PATIENTS UNDERGOING REVASCULARISATION PROCEDURES

Percutaneous coronary intervention

It is well recognised that the myocardium can be damaged after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and cardiac markers may increase in up to a third of patients.10–13 In the majority of cases this is of a minor degree. Causes include side branch occlusion and microembolisation. It is important to bear in mind, just as with spontaneous MI, that cardiac enzyme release after PCI should be integrated with clinical, angiographic, and ECG data to assess prognosis properly. Troponin concentrations should not be considered in isolation.

However, it is clear from several studies that patients with increased cardiac markers after PCI have an adverse short term prognosis and that the risk of adverse events increases with the degree of marker increase.15–24 The longer term significance of small increases of cardiac enzymes after PCI are less certain, whereas marker release of a greater degree is known to have an adverse impact on long term prognosis.23,24 Given this evidence there is no obvious reason why there should be different thresholds for cardiac enzyme release for spontaneous and periprocedural MI. A definition of MI independent of whether the myocardial damage occurred spontaneously or after PCI will also allow a better comparison to be made between medical, interventional, and surgical treatments for coronary artery disease. The impact of cardiac enzyme release after PCI on prognosis reinforces the importance of regular, protocol driven measurement of cardiac markers after these procedures. In many cases, detection of an increased marker will not require specific treatment, but without recognition of the phenomenon proper audit is not possible and advances in preventing myocardial damage during revascularisation procedures are unlikely to be made.

The Working Group recommends systematic measurement of troponins after PCI (> 6 hours) as part of quality control standards.

CORONARY ARTERY BYPASS GRAFTING

After major vascular surgery about 3% of patients experience clinically evident MI based on WHO criteria, but with routine monitoring of troponin or CK-MB, MI is detected in about 12% of patients.23 Similar findings are likely to apply with coronary artery bypass grafting, but the situation is complicated by the release of cardiac markers caused by surgical instrumentation of coronary vessels. Nevertheless, a direct relation exists between the extent of enzyme and marker release and subsequent mortality. In a study from the Mid America Heart Institute, CK-MB increase after coronary artery bypass grafting was an independent predictor of long term mortality, but there appears to be a threshold at about four times the upper limit of normal for CK-MB.25 On the basis of these and other publications routine evaluation of the ECG and cardiac markers after coronary artery bypass grafting is likely to provide useful information on longer term prognosis and on improvement in quality control standards.

DETECTION OF REINFARCTION

Reinfarction and coronary reocclusion after initially successful reperfusion are underrecognised on account of the reduced sensitivity of the ECG in the context of a recent acute infarction and the possibility that enzymes and cardiac markers have not returned to baseline values. Within the first 12–24 hours of an infarction the detection of reinfarction relies on clinical symptoms plus re-elevation of the ST segments in the affected territory of the ECG. Subsequently, a rise in cardiac markers to > 50% above a previous peak concentration has been used in clinical trials as an objective criterion of reinfarction. The long half life of troponins reduces their sensitivity for the detection of reinfarction in the days after an index MI. Shorter half life markers (CK-MB, myoglobin, or cardiac fatty acid binding protein) and agreed thresholds are required to allow consistent and more sensitive detection of reinfarction. CK is less specific but may be used to detect reinfarction before more specific markers are tested.

CONCLUSIONS

The Working Group recommends that patients with an ACS should be categorised as being either without detectable increases in cardiac troponins (ACS with unstable angina) or with myocyte necrosis but troponin increases less than the diagnostic threshold for clinical infarction (troponin T < 1.0 ng/ml, AccuTnI < 0.5 ng/ml, or equivalent other troponin I concentrations), or they should be categorised as having clinical MI when the ECG signs are accompanied by troponin (and or CK-MB) increases above the diagnostic threshold for infarction.

On initial presentation, a working diagnosis of suspected ST elevation infarction is important and urgent, as such patients require emergency reperfusion. Initial presentation with ST elevation is highly specific for subsequent MI but if reperfusion occurs very promptly or spontaneously, infarction may be attenuated and in a small proportion of patients may not be detectable.

Outside of the context of ACS, troponin increase may nevertheless reflect myocyte necrosis and may provide prognostic information. Such conditions should not be confused with ACS.

In the context of ACS, a continuous relation exists between the extent of troponin increase and the extent of MI. Nevertheless, the Working Group recognises that identification of clinically evident MI is useful, as it identifies patients with increased risks of death and more notable evidence of left ventricular dysfunction. The Working Group suggests a threshold of troponin T > 1.0 ng/ml or AccuTnI > 0.5 ng/ml (or equivalent concentrations in other troponin assays) for recognising clinical MI.

The Working Group recommends that all hospital laboratories should ensure that troponin assays meet accuracy standards set out in the ESC/ACC recommendations.1,11 Further, the Working Group strongly recommends that British hospitals should adopt the international reference standard for comparing troponin assays as soon as this becomes available.

Table 5.

Bayer ACS180 versus Roche Elecsys 1010: data from Morrow et al26

| Troponin assay and concentration (ng/ml) | Death at 30 days | Death at 6 and 12 months |

| Elecsys TnT >0.01 | 2.6% | 4.0% |

| Elecsys TnT >0.1 | 2.9% | 4.3% |

| ACS 180 TnI >0.1 | 2.4% | 3.9% |

| ACS 180 TnI >1.5 | 2.6% | 3.8% |

TnI, troponin I; TnT, troponin T.

Table 6.

Data from Morrow et al27

| Troponin assay and concentration (ng/ml) | Death at 30 days | Death/MI at 6 and 12 months |

| BC AccuTnI <0.04 | 0.5% | 3.3% |

| BC AccuTnI >0.04 | 2.0% | 9.0% |

Table 7.

Data from Morrow et al28

| Troponin assay and concentration (ng/ml) | Death at 43 days | Death/MI at 43 days |

| Dimension RxL TnI >0.1 | 5.1% | 13.3% |

| ACS180 TnI >0.1 | 5.4% | 13.7% |

| Immuno 1 TnI >0.1 | 4.7% | 12.9% |

Table 8.

Data from Venge et al29

| Troponin assay and concentration (ng/ml) | Death with marker less than indicated in column 1 at 1 year | Death at 1 year |

| BC AccuTnI >0.02 | 0.7% | 4.5% |

| BC AccuTnI >0.03 | 1.1% | 4.5% |

| AxSym TnI >0.6 | 3.2% | 4.1% |

| AxSym TnI >0.10 | 2.8% | 4.3% |

| Elecsys TnT >0.01 | 1.7% | 4.7% |

| Elecsys TnT >0.03 | 2.6% | 4.4% |

| AxSYM <1.0 ng/ml | AxSYM >1.0 ng/ml | |

| BC AccuTnI <0.03 | 1.2% death at 1 year | Insufficient data |

| BC AccuTnI >0.03 | 5.5% death at 1 year | 4.4% death at 1 year |

Table 9.

Data from Venge et al30

| Troponin assay and concentration (ng/ml) | Liaison cTnI <0.041 ng/ml | Liaison cTnI >0.041 ng/ml |

| BC AccuTnI <0.04 | 5.6% | 9.1% |

| BC AccuTnI >0.04 | 13.2% | 14.0% |

Acute MI or death at six months, n = 3456.

cTnI, cardiac troponin I.

Table 10.

Data from Uettwiller-Geiger et al31

| Troponin assay equivalencies | r | Number |

| AccuTnI = 0.932 (±0.029) Dade RxL−1.039 | 0.980 | 147 |

| AccuTnI = 1.109 (±0.031) Vitros ECi−0.473 | 0.968 | 316 |

| AccuTnI = 0.183 (±0.010) AxSYM+0.062 | 0.946 | 128 |

Poorer correlations are seen if only low concentrations (AccuTnI <1.5 ng/ml) are used.

Table 11.

Data from Lewis et al32

| Troponin assay and concentration (ng/ml) | AxSYM <0.6 ng/ml | AxSYM >0.6 ng/ml |

| ACS:180 <0.12 | NA | 20 |

| ACS:180 >0.12 | 10 | 130 |

163 samples identified with low troponin—selection was biased as no negatives were included; NA, data not available.

Table 12.

Data from Venge et al29

| Troponin assay and concentration (ng/ml) | AxSYM <1.0 ng/ml | AxSYM >1.0 ng/ml |

| BC AccuTnI <0.03 | 1.2% death (6.4% AMI/death) | n = 3 |

| BC AccuTnI >0.03 | 5.5% death (13.8% AMI/death) | 4.4% death (17% AMI/death) |

| Elecsys TnT <0.03 ng/ml | Elecsys TnT >0.03 ng/ml | |

| BC AccuTnI <0.03 | 1.2% death (5.8% AMI/death) | n = 2 |

| BC AccuTnI >0.03 | 5.1% death (14.3% AMI/death) | 4.5% death (16.8% AMI/death) |

Clinical events at 1 year, n = 879.

Table 13.

Data compared by Deming regression: data from Kao et al33

| Troponin assay equivalencies | r | p Value |

| Immulite = 1.505 Vitros−0.154 | 0.99 | <0.0001 |

| Immulite = 0.288 AxSYM−0.475 | 0.97 | <0.0001 |

| Immulite = 0.933 Opus−1.359 | 0.85 | <0.0001 |

| AxSYM = 3.508 Opus − 6.511 | 0.90 | <0.0001 |

| Vitros = 0.191 AxSYM − 0.203 | 0.97 | <0.0001 |

| Vitros = 0.591 Opus − 0.411 | 0.88 | <0.0001 |

Table 14.

UK National External Quality Assessment Service between laboratory comparisons34; lowest concentrations at which between laboratory coefficients of variation are ⩽10%

| Assay | Concentration (ng/ml) |

| TnI | |

| Abbott AxSYM | 4.4 |

| Bayer Immuno 1 | NA |

| Bayer Advia Centaur | 1 |

| Beckman Coulter AccuTnI | 0.65 |

| Dade Dimension | 1.75 |

| Dade Stratus | 1.25 |

| DPC Immulite | NA |

| DPC Immulite 2000 | 2.75 |

| Ortho CD Vitros ECi | 2.0 |

| Tosoh Bioscience AIA | 7.5 |

| TnT | |

| Roche Elecsys 1010 | 0.25 |

| Roche Elecsys 2010 | 0.33 |

Note that many manufacturers are changing and improving their assay methods.

NA, not available.

NB: CV data on the Abbott AxSYM, Vitros Eci, and Tosoh AIA systems are derived from <10 data points.

Abbreviations

ACC, American College of Cardiology

BCS, British Cardiac Society

CK, creatine kinase

ESC, European Society of Cardiology

FRISC, fast revascularisation during instability in coronary artery disease

GRACE, global registry of acute coronary events

MI, myocardial infarction

PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention

PRAIS-UK, prospective registry of acute ischaemic syndromes in the UK

SPECT, single photon emission computed tomography

TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction

WHO, World Health Organization

APPENDIX 1

WORKING GROUP OF THE BRITISH CARDIAC SOCIETY

Keith AA Fox (Chair)

John Birkhead

Robert Wilcox

Charles Knight

Julian Barth

APPENDIX 2

REVIEW OF STUDIES COMPARING TROPONIN ASSAYS IN RELATION TO OUTCOME

The problem with the interpretation of troponin assays is due to many factors including the lack of standardisation and variable analytical performance by the different methods. These factors have led to confusion over the use of a value that can be universally used as a decision point.

Troponin T assays are made by only a single manufacturer and therefore all values are comparable. However, troponin I assays are made by many different manufacturers and, as they use different formulations and standards, results obtained by different methods cannot be compared.

The International Federation of Clinical Chemistry is developing a standard that can be used to help harmonise methods. Until this preparation is available, each method needs to be evaluated. One option for this is to examine the outcome. This is probably the best option despite the current rapid change in treatment regimens.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anon, Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee. Myocardial infarction redefined: a consensus document of the Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2000;21:1502–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox KAA, Goodman SG, Klein W, et al. Management of acute coronary syndromes. Variations in practice and outcome: findings from the global registry of acute coronary events (GRACE). Eur Heart J 2002;23:1177–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collinson J, Flather MD, Fox KAA, et al. Clinical outcomes, risk stratification and practice patterns of unstable angina and myocardial infarction without ST elevation: prospective registry of acute ischaemic syndromes in the UK (PRAIS-UK). Eur Heart J 2000;21:1450–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alpert JS. The not so obvious truth. Eur Heart J 2000;21:180–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJLM, et al. The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: a method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making. JAMA 2000;284:835–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christopher B, Granger, Robert J, et al. Predictors of hospital mortality in the global registry of acute coronary events. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2345–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferguson JL, Beckett GJ, Stoddart M, et al. Myocardial infarction redefined: the new ACC/ESC definition, based on cardiac troponin, increases the apparent incidence of infarction. Heart 2002;88:343–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apple FS. Clinical and analytical standardization issues confronting cardiac troponin I. Clin Chem 1999;45:18–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Apple F, Wu A, Jaffe A. European Society of Cardiology and American College of Cardiology guidelines for redefinition of myocardial infarction: how to use existing assays clinically and for clinical trials. Am Heart J 2002;144:981–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thygesen KA, Alpert JS. The definitions of acute coronary syndrome, myocardial infarction and unstable angina. Curr Cardiol Rep 2002;3:268–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Apple FS, Quist HE, Doyle PJ, et al. Plasma 99th percentile reference limits for cardiac troponin and creatine kinase MB mass for use with European Society Cardiology/American College of Cardiology consensus recommendations. Clin Chem 2003;49:1331–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner A, Mahrholdt H, Holly TA, et al. Contrast-enhanced MRI and routine single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) perfusion imaging for detection of subendocardial myocardial infarcts: an imaging study. Lancet 2003;361:374–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Remppis A, Ehlermann P, Giannitsis E, et al. Cardiac troponin T levels at 96 hours reflect myocardial infarct size: a pathoanatomical study. Cardiology 2000;93:249–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao ACR, Collinson PO, Canepa-Anson R, et al. Troponin T measurement after myocardial infarction can identify left ventricular ejection of less than 40%. Heart 1998;80:223–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akkerhuis KM, Alexander JH, Tardiff BE, et al. Minor myocardial damage and prognosis: are spontaneous and percutaneous coronary intervention-related events different? Circulation 2002;105:554–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simoons ML, van den Brand M, Lincoff M, et al. Minimal myocardial damage during coronary intervention is associated with impaired outcome. Eur Heart J 1999;20:112–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrmann J, von Birgelen C, Haude M, et al. Prognostic implication of cardiac troponin T increase following stent implantation. Heart 2002;87:549–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cantor WJ, Newby LK, Christenson RH, et al. for the SYMPHONY and 2nd SYMPHONY Cardiac Markers Substudy Investigators. Prognostic significance of elevated troponin I after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:1738–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nallamothu BK, Chetcuti S, Mukherjee D, et al. Prognostic implication of troponin I elevation after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2003;91:1272–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuchs S, Kornowski R, Mehran R, et al. Prognostic value of cardiac troponin I levels following catheter-based interventions. Am J Cardiol 2000;85:1077–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saucedo JF, Mehran R, Dangas G, et al. Long-term clinical events following creatine kinase myocardial band isoenzyme elevation after successful coronary stenting. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:1134–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellis SG, Chew D, Chan A, et al. Death following creatine kinase-MB elevation after coronary intervention. Circulation 2002;106:1205–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landesberg G, Shatz V, Akopnik I, et al. Association of cardiac troponin, CK-MB, and postoperative myocardial ischemia with long-term survival after major vascular surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1547–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panteghini M, Pagani F, Yeo K-TJ, et al. Evaluation of imprecision for cardiac troponin assays at low-range concentration. Clin Chem 2004;50:327–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marso SP, Bliven BD, House JA, et al. Myonecrosis following isolated coronary artery bypass grafting is common and associated with an increased risk of long-term mortality. Eur Heart J 2003;24:1323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrow DA, Cannon CP, Rifait N, et al. Ability of minor elevations of troponins I and T to predict benefit from an early invasive strategy in patients with unstable angina and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction: results from a randomized trial. JAMA 2001;286:2405–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morrow DA, Rifai N, Sabatine MS, et al. Evaluation of the AccuTnI cardiac troponin I assay for risk assessment in acute coronary syndromes. Clin Chem 2003;49:1396–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morrow DA, Rifai N, Tanasijevic MJ, et al. Clinical efficacy of three assays for cardiac troponin I for risk stratification in acute coronary syndromes: a thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) 11B substudy. Clin Chem 2000;46:453–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venge P, Lagerqvist B, Diderholm E, et al. Clinical performance of three cardiac troponin assays in patients with unstable coronary artery disease (a FRISC II substudy). Am J Cardiol 2002;89:1035–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venge P, Johnston N, Lagerqvist B, et al. Clinical and analytical performance of the Liaison cardiac troponin I assay in unstable coronary artery disease, and the impact of age on the definition of reference limits. A FRISC-II substudy. Clin Chem 2003;49:880–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uettwiller-Geiger D, Wu AH, Apple FS, et al. Multicentre evaluation of an automated assay for troponin I. Clin Chem 2002;48:869–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis JS Jr, Taylor JF, Miklos AZ, et al. Clinical significance of low-positive troponin I by AxSYM and ACS:180. Am J Clin Pathol 2001;116:396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kao JT, Wong IL, Lee JY, et al. Comparison of Abbott AxSYM, Behring Opus Plus, DPC Immulite and Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics Vitro ECi for measurement of cardiac troponin I. Ann Clin Biochem 2001;38:140–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anon. Annual report April 2002 to March 2003. Bristol: UK NEQAS for Antibiotic Assays, 2003.