The management of patients with ST segment elevation acute myocardial infarction has evolved considerably during the last decades. Restoration of coronary flow can be achieved pharmacologically by the administration of thrombolytic or fibrinolytic drugs, which are widely available and easy to administer, or mechanically by means of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) with or without antecedent drug treatment, which is less available and more complex to implement and carry out. The two strategies are currently subject of a vivid debate by protagonists and antagonists of the two approaches. This paper summarises the available evidence with emphasis on the randomised comparisons of direct PTCA with thrombolysis. These studies and findings are open for interpretation. They are reviewed and discussed, and a rational and pragmatic approach is proposed.

SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is a frequent clinical condition associated with a high immediate and short term mortality and long term morbidity. The pre-hospital case fatality rate is approximately 32%, and is most often caused by malignant arrhythmias.1 In-hospital mortality of those patients who reach the hospital alive is 8–15%.1w1 In case of survival, the patient may become severely incapacitated because of heart failure as a result of the loss of normal functioning myocardium and ventricular remodelling.w2

In almost all patients, AMI is caused by an acute thrombotic coronary occlusion following the rupture of the cap of an atherosclerotic plaque.w3 The associated ischaemic injury and subsequent myocardial necrosis spreads from the subendocardial to the subepicardial myocardium in a time span of several hours.w4 Irreversible loss of subendocardial cardiomyocytes occurs after 30 minutes while subepicardial cardiomyocytes may survive for up to six hours. Therefore, to save the patient from sudden death and to save the ventricle, thus preventing heart failure, early diagnosis and treatment are imperative.

Myocardial salvage depends on the prompt, complete, and sustained restoration of myocardial perfusion. At present, this can only be obtained by re-establishing coronary flow, although coronary reperfusion does not necessarily imply myocardial perfusion.w5 In practice, the choice between thrombolysis and PTCA depends on, among others, physician preferences, availability of infrastructure, economic factors, and time of admission, rather than clinical evidence.2w1 w6

THE CASE FOR THROMBOLYTIC TREATMENT

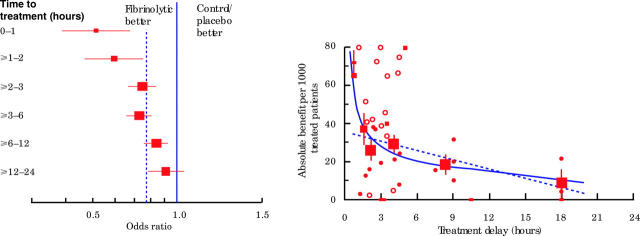

A vast number of trials have consistently and unequivocally proven that thrombolysis reduces infarct size and mortality and improves long term outcome.3 The benefit of treatment is observed in patients with different levels of risk. Patients who present early and who receive treatment within two hours after onset of symptoms benefit the most (fig 1).3,4 Thrombolytic drugs can now be administrated by a single bolus; thus, this approach is applicable in almost all circumstances and can be started in the very early phase of AMI, even before hospital admission. Pre-hospital initiation of treatment may save one hour in comparison to the in-hospital administration and is associated with a fourfold higher incidence of aborted infarction (17.1% v 4.5%) and an absolute reduction of 2.0% (relative 17%) in hospital mortality.5w7 On-site initiation of treatment is the unsurpassed opportunity of early management since public education has failed to make patients seek help earlier.w8

Figure 1.

Left panel: Proportional 35 day mortality reduction is highest in patients treated within one hour (48%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 31% to 61%) and within two hours (44%, 95% CI 32% to 53%) versus those treated later (20%, 95% CI 15% to 25%). Right panel: Relation between absolute benefit of thrombolytic treatment and treatment delay described by a linear and a non-linear function. There is a reduction in benefit of approximately 1.6 (0.5) lives per 1000 patients per hour treatment delay. Benefit of fibrinolytic treatment was (mean (SD)) 65 (14), 37 (9), 26 (6), and 29 (5) lives saved per 1000 treated patients in the 0–1, 1–2, 2–3, and 3–6 hour intervals, respectively. Reproduced from Boersma et al,4 with permission.

Thrombolysis, nonetheless, has a number of limitations that affects its application and efficacy. It fails to induce complete restoration of coronary flow (TIMI (thrombolyis in myocardial infarction) grade 3) in 30–40% of the patients, and early reocclusion occurs in 5–6% of the patients.w9 Because of the inherent risk of bleeding, thrombolysis cannot be used in patients with bleeding disorders, those receiving anticoagulant drugs, or patients who have undergone recent surgery or trauma. Intracranial haemorrhage is the most extreme complication. It occurs in approximately 1% of patients but may exceed 2% depending on the number of risk factors present.w10 Thrombolysis does not resolve the underlying plaque and stenosis. The residual stenosis may cause ischaemia that may hamper ventricular recovery. These limitations have stimulated the (re)appraisal of mechanical reperfusion.

WHY DIRECT OR PRIMARY PTCA?

The first comparisons of PTCA without previous or concomitant thrombolytic treatment (direct or primary PTCA) with in-hospital thrombolysis revealed that direct PTCA is associated with a higher proportion of patients reaching TIMI 3 flow (90%), and a better left ventricular function, lower incidence of mortality, reinfarction, stroke, recurrent ischaemia, and bleeding complications.6,7 Analysis of 23 randomised studies confirmed the superiority of direct PTCA in the reduction of death, reinfarction, and stroke at 30 days, even when the patient is transferred from one hospital to the other (table 1).8 As a result, direct PTCA became embraced as the first choice treatment of AMI. It is in line with the proposal of the National Heart Attack Alert Program to send patients with an AMI to a PTCA centre, similar to trauma patients, and not to the nearest hospital.w11 It dissents, however, with the opinion of the NRMI investigators who found a similar in-hospital and 90 day mortality rate in more than 305 000 patients, irrespective of the admission to a community or tertiary referral center (table 2).2 They proposed to treat patients with AMI at the closest medical facility, rather than sending them to a regional centre with specialised facilities.

Table 1.

Short term clinical outcome after direct PTCA and thrombolytic treatment

| PTCA | Thrombolysis | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Absolute risk difference | Number to treat | |

| Patients (n) | 3717 | 3720 | |||

| Death | 5.0 | 7.0 | 0.70 (0.6 to 0.9) | 2.0 | 50 |

| Non-fatal reinfarction | 3.0 | 7.0 | 0.35 (0.3 to 0.5) | 4.0 | 25 |

| Stroke | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.46 (0.3 to 0.7) | 1.0 | 100 |

| Intracranial haemorrhage | 0.05 | 1.0 | 0.05 (0.006 to 0.35) | 0.95 | 105 |

| Composite | 8.0 | 14.0 | 0.5 (0.45 to 0.6) | 6.0 | 16 |

Events are expressed in relative numbers (%).

Patients with AMI complicated by cardiogenic shock are not included in this analysis.w20

Modified from Keeley et al,8 with permission.

Table 2.

In-hospital events of patients with AMI admitted in different types of hospitals

| Non-invasive | Cath capable No PTCA | PTCA capable | PTCA and CABG capable | |

| Patients (n) | 57252 | 76956 | 24451 | 147153 |

| Death | 10.2 | 10.4 | 10.0 | 11.3 |

| Reinfarction | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.7 |

| Stroke | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.6 |

| Major bleeding | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 3.0 |

Events are expressed in relative numbers (%).

Modified from Rogers et al,2 with permission.

ARGUMENTS IN FAVOUR FOR REFERRING EVERY PATIENT FOR DIRECT PTCA

The strongest argument for referring every patient for direct PTCA is the better clinical outcome after direct PTCA (table 1).8 An even better outcome after PTCA may have occurred in these studies if state of the art PTCA techniques had been used. Stents were used to a varying degree in only 50% of the studies and a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blocker in only 25%, despite the superiority of stents over balloon angioplasty to prevent restenosis, and the recognised value of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockers to prevent thrombotic complications.w12 w13 This contrasts with the use of the most powerful thrombolytic drug in patients assigned to thrombolysis. Accelerated tissue plasminogen activator (acc t-PA), which is associated with a higher TIMI 3 rate and survival benefit than streptokinase, was used in most of the studies and patients (69%).8w14 Of note is the superiority of PTCA when patients were transported from a community hospital to a PTCA centre, despite a delay in the onset of treatment of approximately 40 minutes (tables 3 and 4).8–10

Table 3.

Study design and use of reperfusion strategies in studies with interhospital or direct transport of patients to PTCA centre

| Study | Patients | Randomisation | Thrombolysis | PTCA |

| PRAGUE-2 | ST ↑ AMI <12 h | In community hospital without PTCA facility to: | Streptokinase | Stents used in 63% |

| Thrombolysis or direct PTCA | ||||

| provided start interhospital transport | ||||

| possible within 30 mins and distance <120 km | ||||

| DANAMI-2 | ST ↑ AMI <12 h | In community hospitalor PTCA centre to: | Accelerated (acc) t-PA | Stents used in 81% |

| Thrombolysis or direct PTCA | Glycoprotein IIb/IIIA blocker in 39% | |||

| if admitted in community hospital: | ||||

| provided transport to PTCA centre completed within 3 hours | ||||

| CAPTIM | ST ↑ AMI <6 h | On site to: | Pre-hospital acc t-PA | Stents used in 81% |

| thrombolysis or direct PTCA + transport to PTCA centre, provided transport duration <1 hour | With rescue PTCA strategy | Glycoprotein IIb/IIIA blocker in 39% |

Use of rescue PTCA: in DANAMI-2 study 1.9%, CAPTIM study 26%, PRAGUE-2 study 6.4%. Any PTCA at 30 days: in DANAMI-2 study 16.5%, CAPTIM study 70.4%.

Table 4.

Clinical events at 30 days in studies with interhospital or direct transport of patients to a PTCA centre

| PRAGUE-2 | DANAMI-2 | CAPTIM | |||||

| Lysis | PTCA | Lysis | PTCA | Lysis | PTCA | ||

| Patients (n) | 421 | 429 | 782 | 790 | 419 | 421 | |

| Death | 10.0 | 6.2 | 7.8 | 6.6 | 3.8 | 4.3 | |

| Reinfarction | 3.1 | 1.4 | 6.3 | 1.6* | 3.7 | 1.7 | |

| Stroke | 2.1 | 0.2* | 2.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.0 | |

| Composite | 15.2 | 8.4* | 13.7 | 8.0* | 8.2 | 6.2 | |

| Rescue PTCA | 6.4 | 1.9 | 26.0 | ||||

| Any PTCA at 30 days | NR | 16.5 | 70.4 | ||||

All values are expressed as relative numbers (%).

*Outcomes which reached the level of significance.

NR, not recorded.

Similarly, the outcome in the thrombolytic treated patients may have been better with a more liberal use of rescue PTCA. Rescue PTCA was applied in a minority of the patients, except for those in the CAPTIM study (tables 3 and 4).9–11 The role of systematic PTCA rather than rescue PTCA is unclear. The first randomised studies failed to show an additional benefit of systematic PTCA after thrombolysis, while a recent study reported a better outcome when stent implantation was performed within six hours after thrombolysis in comparison to a delayed elective intervention at two weeks.12–15

COMMENTS AND UNRESOLVED ISSUES

The patients enrolled in the randomised studies may not be representative of those seen in daily practice. In general, they have a lower baseline risk because of the inclusion and exclusion criteria (for example, eligibility for both thrombolysis and PTCA) and selection bias. The open design, physician preferences or prejudices, and logistical aspects dictated by, for example, time of presentation may explain the latter. In both the NRMI registry and the C-PORT study, most patients underwent PTCA during the office hours.2,16 The initiation of treatment takes longer during out-of-office hours, in particular for more complex treatments such as PTCA. This may affect outcome since time to treatment is a main determinant of outcome. This has been clearly established for thrombolysis (fig 1) but is less apparent in the case of PTCA.3,4,17w15 w16 An increasing door-to-balloon time was related to an increased mortality in one study, but was not confirmed by two other analyses.17w15 w16 Other data suggest that direct PTCA is superior to thrombolysis provided the added delay is less than 60–90 minutes.w17 Longer delays are associated with increased mortality.w18 The established relation between time and outcome in the thrombolytic studies but discrepant findings in the PTCA studies may be explained by the fact that few patients in the PTCA studies were enrolled in the (very) early phase of AMI when most of the salvage may be achieved.

Also, the results of the randomised studies may not be repeated in less ideal settings. The NRMI investigators found that the mortality at discharge was 3.4% after direct PTCA compared with 5.4% after thrombolysis in high volume PTCA centres (4.5% v 5.9% in intermediate volume centres, and 6.2% v 6.0% in low volume centres).18 With adequate preparation and training, direct PTCA may be superior to thrombolytic treatment in less experienced centres. The C-PORT study compared direct PTCA with thrombolysis in 541 patients admitted to hospitals without on-site surgical back up or a pre-existing PTCA programme.16 A significant and sustained reduction in the incidence of the composite adverse outcome of death (5.3% v 7.1%), recurrent infarction (4.9% v 8.8%), and stroke (1.3% v 3.5%) was observed after PTCA.

The incidence of mortality and reinfarction in the randomised trials is lower than in population based surveys and, despite a large relative reduction in events after direct PTCA, the absolute difference in outcome between thrombolysis and PTCA is much smaller (tables 1 and 2).1,2w1 The latter provides the estimate of the number of patients who need to be treated to save one from a particular event and can be used to evaluate treatment (table 1). Despite the small absolute differences, the direction of benefit for all outcome measures favours direct PTCA. This is especially true for reinfarction, which is associated with a high mortality and further deterioration of the ventricular function.

Costs and logistics need to considered as well. The costs of direct PTCA increase considerably in hospitals without full existing resources or with a low annual caseload.w19 In addition, a lack of infrastructure may impede delivery of care. Less than 10% and 25% of hospitals in Europe and the USA, respectively, have PTCA facilities.w9 An acute PTCA programme implies an availability of a dedicated medical and paramedical team on a 24 hour/seven day a week basis. Because of practical limitations, it is expected that the short door-to-balloon times reported in the randomised trials will not be repeated in the real world.w9

A PRAGMATIC APPROACH

There is no evidence that every patient with an evolving AMI should be referred for direct PTCA. The choice of treatment should be based upon an assessment of the baseline risk of the individual patient, and a risk/benefit evaluation of the possible treatment modalities and logistics. Some patients (the elderly, patients with antecedents of heart failure, diabetes, stroke or bypass surgery, patients with an anterior infarction and/or signs of heart failure or shock at admission) are at increased risk.6 They benefit more from direct PTCA than from thrombolytic treatment, although it should be appreciated that this information stems from post-hoc subgroup analyses.w20–22

The time interval from onset of symptoms to presentation should have a central role in the selection of treatment. None of the randomised comparisons fully took advantage of the possibility of early diagnosis and initiation of treatment on site, before transportation or admission, except for the CAPTIM study.11 Patients were randomised at the site of initial management, most often at home or the workplace, to either pre-hospital thrombolysis or transport for direct PTCA. Patients randomised to pre-hospital thrombolysis were also transported to a PTCA centre for rescue PTCA. The latter was decided upon at the discretion of the attending physician. The median time delay between onset of symptoms and initiation of treatment was 130 minutes for pre-hospital thrombolysis and 190 minutes for direct PTCA. Rescue PTCA was performed in 26% of the thrombolytic patients. At variance with all other studies, direct PTCA was not better than the pre-hospital thrombolysis strategy (tables 1 and 4). More interestingly, a subgroup analysis disclosed a strong trend toward a lower mortality and less cardiogenic shock in patients treated with pre-hospital thrombolysis within two hours after onset of symptoms (table 5).19 In patients presenting later than two hours after onset of symptoms, there was a trend of superiority of direct PTCA.

Table 5.

Incidence of events after direct PTCA and thrombolytic treatment according to time between onset of symptoms and randomisation

| <2 hours | ⩾2 hours | |||||

| Pre-hospital lysis | Direct PTCA | Pre-hospital lysis | Direct PTCA | |||

| Time to therapy (mins) | 95 (40–175) | 150 (82–260) | <0.0001 | 195 (120–570) | 258 (150–1275) | <0.0001 |

| Death | 2.2 | 5.7 | 0.06 | 5.9 | 3.7 | NS |

| Reinfarction | 4.0 | 1.4 | NS | 3.4 | 2.2 | NS |

| Stroke | 1.3 | 0.0 | NS | 0.6 | 0.0 | NS |

| Cardiogenic shock | 1.3 | 5.3 | 0.03 | 3.9 | 4.4 | NS |

Events are expressed in relative numbers (%), median time with interquartile range.

NS, not significant.

Modified from Steg et al,19 with permission.

This was also found in a subgroup analysis of the PRAGUE-2 study that revealed a similar 30 day mortality with in-hospital thrombolysis with streptokinase and direct PTCA in patients presenting within three hours (7.3% v 7.4%); however, if treated after three hours, 30 day mortality with thrombolysis rose considerably compared to PTCA (15.3% v 6.0%, respectively).9

Such an effect was not observed in the DANAMI-2 study.10 In this study 1572 patients were randomised to direct PTCA or acc t-PA. In total, 1129 patients (72%) were randomised in a community hospital, and 567 were subsequently transported to a PTCA centre for direct PTCA. The median interhospital transport time was 32 minutes. No pharmacological treatment aimed at the restoration of flow was started before transport. The median door-to-balloon time of patients directly admitted to the PTCA centre was 26 minutes, while for those patients initially admitted to a community hospital it was 93 minutes. The main study finding was a 40% relative reduction in the composite outcome (30 day death, reinfarction, stroke) in patients enrolled in the community hospitals and 45% in patients enrolled in the PTCA centres in favour of direct PTCA. The benefit of direct PTCA was driven by a 75% relative reduction in reinfarction (1.6% v 6.3%), whereas there was no difference in death and stroke. At variance with the CAPTIM and PRAGUE study, direct PTCA was also superior to thrombolysis in patients admitted within two hours. This discrepancy is unclear. A subgroup effect cannot be excluded and may have biased the results. The advantage of thrombolysis over direct PTCA in patients presenting and being treated early is, nonetheless, plausible. These patients have a fresh thrombus, which is easily dissolved by a thrombolytic drug, especially when administered very early.

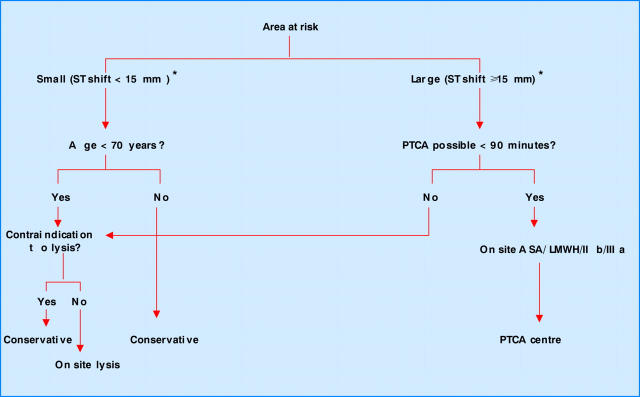

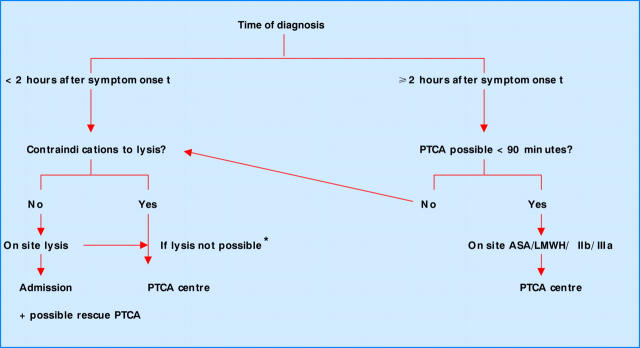

Rather than referring every single patient with an AMI for direct PTCA, an integrated approach as proposed previously and by others appears to be more appropriate.20w23 w24 It is based upon the assessment of: (1) time interval from onset of symptoms to presentation; (2) baseline risk derived from clinical examination and ECG; (3) risk/benefit assessment of treatment (bleeding and intracranial bleeding, in particular; and (4) availability and estimated time from presentation to PTCA which includes transportation and door-to-balloon time.

Two algorithms have been proposed (figs 2 and 3) The first uses the estimated myocardial area at risk (total ST shift and number of leads with shift) as the primary selection criterion.w23 The other takes the time interval between symptom onset and presentation as the starting point.20w24 In both algorithms, pre-hospital thrombolysis is advocated for patients seen very early in the course of an infarct. The choice of the algorithm may depend on regional and institutional issues such as population density and geography, infrastructure, agreements with ambulance services, health insurance companies, and policymakers.

Figure 2.

Management of patients with ST segment elevation acute myocardial infarction and presentation ⩽ 6 hours. ASA, aspirin; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty.

Figure 3.

Management of patients with ST segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. *Consider PTCA if on site lysis not possible.

While there is consensus that thrombolysis should comprise the pre-hospital administration of the lytic drug, preferably as a single bolus, in combination with aspirin and weight adjusted low molecular weight heparin, the initial pharmacology strategy in patients referred for direct PTCA is the subject of investigation.w25 The objective is to induce the TIMI 3 flow before the patient arrives in the catheterisation laboratory without the risk of major bleeding. Abciximab before but not at the time of PTCA has been shown to improve outcome.w13

SUMMARY

All randomised comparisons have shown that direct PTCA is superior to thrombolysis in patients with AMI. Yet the choice of treatment strategy should depend on the careful evaluation of the risk/benefit of treatment. Issues unrelated to this assessment will most likely influence the selection of treatment in daily practice. Two algorithms have been proposed which differ in the primary selection or triage criterion (area at risk versus time interval). Based upon local and regional factors, one or the other may be chosen.

The role of rescue and systematic PTCA after thrombolysis needs further elucidation. At present, it cannot be proposed as a standard treatment.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Chambless L , Keil U, Dobson A, et al. Population versus clinical view of case fatality from acute coronary heart disease. Results from the WHO Monica Project 1985–1990. Circulation 1997;96:3849–59. ▸ World Health Organization MONICA project providing detailed information of case fatality rate during various phases of AMI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers W , Canto J, Barron H, et al. Treatment and outcome of myocardial infarction in hospitals with and without invasive capability. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:371–9. ▸ Large US registry reporting treatment and outcome of more than 300 000 patients with AMI admitted in more than 1500 hospitals with different infrastructure. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fibrinolytic Therapy Trialists’ (FFT) Collaborative Group. Indications for fibrinolytic therapy in suspected acute myocardial infarction: collaborative overview of early mortality and major morbidity results from all randomised trials more than 1000 patients. Lancet 1994;343:311–22. ▸ Landmark review of the effect of thrombolysis in placebo controlled randomised studies with more than 1000 patients. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boersma E , Maas AC, Deckers JW, et al. Early thrombolytic treatment in acute myocardial infarction: reappraisal of the golden hour. Lancet 1996;348:771–5. ▸ Meta-analysis of placebo controlled randomised studies underscoring the key role of time in AMI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrison LJ, Verbeek PR, McDonald AC, et al. Mortality and prehospital thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2000;283:2686–92. ▸ Meta-analysis of the randomised studies comparing pre- and in-hospital thrombolysis. Time reduction saves the myocardium. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grines C , Browne K, Marco J, et al. A comparison of immediate angioplasty with thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1993;328:673–9. ▸ One of three randomised studies published at the same time in the same journal comparing PTCA and thrombolysis, which boosted direct PTCA and a new era of infarct management. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zijlstra F , de Boer MJ, Hoorntje J, et al. A comparison of immediate coronary angioplasty with intravenous streptokinase in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1993;328:680–4. ▸ See reference 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet 2003;361:13–20. ▸ Analysis of 23 randomised comparisons summarising the superiority of direct PTCA in comparison to in-hospital thrombolysis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Widimsky P , Budesinsky T, Vorac D, et al. Long distance transport for primary angioplasty vs immediate thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction. Prague-2 Study. Eur Heart J 2003;24:94–104. ▸ Immediate transfer for PTCA is safe and lowers mortality in comparison to streptokinase. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson H , Nielsen T, Rasmussen K, et al. A comparison of coronary angioplasty with fibrinolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2003;349:733–42. ▸ Transfer for direct PTCA is superior to in-hospital thrombolysis provided transfer is within ⩽2 hours. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonnefoy E , Lapostolle F, Leizorowicz A, et al. Primary angioplasty versus prehospital fibrinolysis in acute myocardial infarction: a randomised study. Lancet 2002;360:825–9. ▸ Transfer for direct PTCA is not better than pre-hospital thrombolysis with a rescue PTCA option. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Topol E , Califf R, George B, et al. Randomized trial of immediate versus delayed elective angioplasty after tissue plasminogen activator in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1987;317:581–8. ▸ Randomised comparison reporting absence of benefit after a systematic invasive strategy in comparison to a delayed invasive strategy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simoons M , Arnold A, Betriu A, et al. Thrombolysis with tissue plasminogen activator in acute myocardial infarction: no additional benefit from immediate PTCA. Lancet 1988;i:197–203. ▸ Randomised study reporting absence of benefit after immediate PTCA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.TIMI Study Group. Comparison of invasive and conservative strategies after tissue plasminogen activator in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1989;320:618–27. ▸ Largest randomised study disclosing no benefit of a systematic invasive strategy compared to an ischaemia guided invasive strategy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scheller B , Hennen B, Hammer B, et al. Beneficial effects of immediate stenting after thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:634–41. ▸ At variance with the early studies, this randomised study revealed the benefit of routine stenting after thrombolysis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aversano T , Aversano L, Passamani E, et al. Thrombolysis vs primary percutaneous coronary intervention for myocardial infarction in patients presenting to hospitals without on-site cardiac surgery. JAMA 2002;287:1943–51. ▸ Randomised study reporting that direct PTCA is superior to thrombolysis in centres without a PTCA programme or surgical standby provided adequate preparation, training, organisation, and monitoring of procedures. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schomig A , Ndrepepa G, Mehilli J, et al. Therapy-dependent influence of time-to-treatment interval on myocardial salvage in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with coronary artery stenting or thrombolysis. Circulation 2003;108:1084–8. ▸ Clinical pathophysiological study revealing that PTCA is less time sensitive than thrombolysis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magid D , Calonge B, Rumsfeld J, et al. Relation between hospital primary angioplasty volume and mortality for patients with acute MI treated with primary angioplasty vs thrombolysis. JAMA 2000;284:3131–8. ▸ Substudy of the NRMI registry revealing the relation between outcome after direct PTCA and experience, case load, and organisation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steg PG, Bonnefoy E, Chabaud S, et al. Impact of time to treatment on mortality after prehospital fibrinolysis or primary angioplasty. CAPTIM randomized clinical trial. Circulation 2003;108:2851–6. ▸ Subanalysis of the CAPTIM study indicating that thrombolysis is superior to direct PTCA in case of early presentation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armstrong PW, Collen D, Antmann E. Fibrinolysis for acute myocardial infarction. The future is here and now. Circulation 2003;107:2533–7. ▸ Objective point of view on both thrombolysis and direct PTCA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.