Hypertension is the most common medical problem encountered in pregnancy and remains an important cause of maternal, and fetal, morbidity and mortality. It complicates up to 15% of pregnancies and accounts for approximately a quarter of all antenatal admissions. The hypertensive disorders of pregnancy cover a spectrum of conditions, of which pre-eclampsia poses the greatest potential risk and remains one of the most common causes of maternal death in the UK.

NORMAL PHYSIOLOGICAL CHANGE IN BLOOD PRESSURE DURING PREGNANCY

Early in the first trimester there is a fall in blood pressure caused by active vasodilatation, achieved through the action of local mediators such as prostacyclin and nitric oxide. This reduction in blood pressure primarily affects the diastolic pressure and a drop of 10 mm Hg is usual by 13–20 weeks gestation.1 Blood pressure continues to fall until 22–24 weeks when a nadir is reached. After this, there is a gradual increase in blood pressure until term when pre-pregnancy levels are attained. Immediately after delivery blood pressure usually falls, then increases over the first five postnatal days.w1 Even women whose blood pressure was normal throughout pregnancy may experience transient hypertension in the early post partum period, perhaps reflecting a degree of vasomotor instability.

DEFINITION OF HYPERTENSION IN PREGNANCY AND BLOOD PRESSURE MEASUREMENT

Hypertension in pregnancy is diagnosed either from an absolute rise in blood pressure or from a relative rise above measurements obtained at booking. The convention for the absolute value is a systolic > 140 mm Hg or a diastolic > 90 mm Hg. However, it should be recognised that blood pressure is gestation related. A diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg is 3 standard deviations (SD) above the mean for mid pregnancy, 2 SD at 34 weeks, and 1.5 SD at term.w2 The definition for a relative rise in blood pressure incorporates either a rise in systolic pressure of > 30 mm Hg or rise in diastolic pressure of > 15 mm Hg above blood pressure at booking. Blood pressure must be elevated on at least two occasions and measurements should be made with the woman seated and using the appropriate cuff size. Late in the second trimester and in the third trimester, venous return may be obstructed by the gravid uterus and, if supine, blood pressure should be taken with the woman lying on her side.

Korotkoff phase I and V (disappearance) should be used, rather than phase IV (muffling), since it is more reproducible2 and shows better correlation with true diastolic blood pressure in pregnancy.3 If phase V is not present, phase IV should be recorded. Automated systems for blood pressure measurement have been shown to be unreliable in severe pre-eclampsiaw3–4 and tend to under record the true value.

CLASSIFICATION OF HYPERTENSIVE DISORDERS OF PREGNANCY

There are three types of hypertensive disorders:

chronic hypertension

gestational hypertension

pre-eclampsia

Chronic hypertension

Chronic hypertension complicates 3–5% of pregnancies4 although this figure may rise, with the trend for women to postpone childbirth into their 30s and 40s. The diagnosis of chronic hypertension is based on a known history of hypertension pre-pregnancy or an elevated blood pressure ⩾ 140/90 mm Hg before 20 weeks gestation.5 However, there are several caveats to this diagnosis. Undiagnosed hypertensive women may appear normotensive in early pregnancy because of the normal fall in blood pressure, commencing in the first trimester. This may mask the pre-existing hypertensionw5 w6 and when hypertension is recorded later in the pregnancy it may be interpreted as gestational. Sometimes the diagnosis is only made several months post partum, when the blood pressure fails to normalise as would be expected with gestational hypertension. Furthermore, pre-eclampsia can rarely present before 20 weeks gestation and may be misinterpreted as chronic hypertension.w7

The presence of mild pre-existing hypertension approximately doubles the risk of pre-eclampsia but also increases the risk of placental abruption and growth restriction in the fetus.w8 In general, when blood pressure is controlled, such women do well and have outcomes not dissimilar to normal women.w6 However, when chronic hypertension is severe (a diastolic blood pressure > 110 mm Hg before 20 weeks gestation) the risk of pre-eclampsia is as high as 46%6 with resultant raised maternal and fetal risks.

Gestational hypertension

Hypertension occurring in the second half of pregnancy in a previously normotensive woman, without significant proteinuria or other features of pre-eclampsia, is termed gestational or pregnancy induced hypertension. It complicates 6–7% of pregnancies7 and resolves post partum. The risk of superimposed pre-eclampsia is 15–26%,8 but this risk is influenced by the gestation at which the hypertension develops. When gestational hypertension is diagnosed after 36 weeks of pregnancy, the risk falls to 10%.8 With gestational hypertension, blood pressure usually normalises by six weeks post partum.

Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Pre-eclampsia usually occurs after 20 weeks gestation and is a multi-system disorder. It was classically defined as a triad of hypertension, oedema, and proteinuria, but a more modern definition of pre-eclampsia concentrates on a gestational elevation of blood pressure together with > 0.3 g proteinuria per 24 hours. Oedema is no longer included because of the lack of specificity.5 Pre-eclampsia may also manifest, with few maternal symptoms and signs, as isolated intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). Eclampsia is defined as the occurrence of a grand mal seizure in association with pre-eclampsia, although it may be the first presentation of the condition.

The incidence of pre-eclampsia is very much influenced by the presence of existing hypertension, although other risk factors are recognised (table 1).9 Overall pre-eclampsia complicates 5–6% of pregnancies,w9 but this figure increases to up to 25% in women with pre-existing hypertension.w6 w9 Eclampsia complicates 1–2% of pre-eclamptic pregnancies in the UK. An estimated 50 000 women die annually from pre-eclampsia worldwide9 and morbidity includes placental abruption, intra-abdominal haemorrhage, cardiac failure, and multi-organ failure. In the last confidential enquiry into maternal deaths there were 15 confirmed deaths from pre-eclampsia or eclampsia, the majority as a result of intracerebral haemorrhage.10 The risks to the fetus from pre-eclampsia include growth restriction secondary to placental insufficiency, and premature delivery. Indeed, pre-eclampsia is one of the most common causes of prematurity (accounting for 25% of all infants with very low birth weight, < 1500 g).

Table 1.

Risk factors for developing pre-eclampsia

| • Nulliparity |

| • Multiple pregnancy |

| • Family history of pre-eclampsia |

| • Chronic hypertension |

| • Diabetes |

| • Increased insulin resistance |

| • Increased body mass index |

| • Hypercoagulability (inherited thrombophilia) |

| • Renal disease even without significant impairment |

| • Low socioeconomic status |

| • Antiphospholipid syndrome (acquired thrombophilia) |

| • Previous pre-eclampsia |

| • Hydatidiform mole |

| • Black race |

Pathogenesis of pre-eclampsia

The pathogenesis and manifestations of pre-eclampsia can be considered in a two stage model. The primary stage involves abnormal placentation. In the first trimester, in a healthy pregnancy, the trophoblast invades the uterine decidua and reaches the inner layer of the myometrium. This migration transforms the small, musculo-elastic spiral arteries into large (fourfold increase in diameter) sinusoidal vessels resulting in a high capacitance, low resistance blood supply to the intervillous space. Although commencing in the first trimester, the change is completed in the second trimester when another wave of trophoblast migration alters the myometrial segments of the arteries.w10 In pre-eclampsia, these vascular alterations do not occur or they are limited to vessels in the decidua.w11 w12 In addition to the failure of demuscularisation, the arteries maintain their response to vasomotor influencesw13 and undergo accelerated atherosclerosis, which further impairs perfusion to the intervillous space.

The secondary stage of pre-eclampsia involves the conversion of this uteroplacental maladaption to the maternal systemic syndrome, which has protean manifestations (table 2). Failure of the normal cardiovascular changes of pregnancy to take place results in hypertension, reduction in plasma volume, and impaired perfusion to virtually every organ of the body. There is vasospasm and activation of platelets and the coagulation system, resulting in microthrombi formation. The link between the placenta and the systemic disorder appears to involve endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress.11–13w14 The management of pre-eclampsia essentially focuses on recognition of the condition and ultimately the delivery of the placenta, which is curative. Since pre-eclampsia may arise with few symptoms, all women are screened during pregnancy through regular antenatal care. Those women who are recognised to be at increased risk have additional screening and more intensive monitoring.

Table 2.

Symptoms and signs of severe pre-eclampsia

| • Left upper quadrant/epigastric pain due to liver oedema ± hepatic haemorrhage |

| • Headache ± visual disturbance (cerebral oedema) |

| • Occipital lobe blindness |

| • Hyperreflexia ± clonus |

| • Convulsions (cerebral oedema) |

MANAGEMENT OF HYPERTENSION IN PREGNANCY

Pre-pregnancy counselling

Up to 50% of pregnancies in the UK are unplanned and thus pre-pregnancy counselling may not be feasible. In women with chronic hypertension, assessment before conception permits exclusion of secondary causes of hypertension (for example, renal/endocrine), evaluation of their hypertensive control to ensure it is optimal, discussion of the increased risks of pre-eclampsia, and education about any drug alterations which would need to be made in the first trimester should they become pregnant. The majority of women with controlled chronic hypertension will, under close supervision and appropriate management, have a successful outcome. Poorly controlled hypertension in the first trimester will significantly increase maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. It must be stressed that none of the many antihypertensive agents used in routine practice have been shown to be teratogenic and women can safely conceive while taking medication. However, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) need to be withdrawn in the first trimester since they are fetotoxic (see below). Women who have experienced poor obstetric outcomes in previous pregnancies because of severe pre-eclampsia, or those at particular risk, need to be counselled about the condition and offered prophylactic treatment with low dose aspirin.14 Since pre-eclampsia involves endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress, there is interest in supplementation, with antioxidant vitamins C and E, in the second trimester. A preliminary trial of antioxidant vitamins, in high risk women, has reported improvements in biochemical markers of endothelial activation together with a reduction in pre-eclampsia15 and a large, nationwide, randomised trial is underway.

Antenatal care

General maternal care

Blood pressure assessment and the search for proteinuria form the cornerstone of antenatal screening of all pregnant women for pre-eclampsia. If “white coat” hypertension is suspected, ambulatory monitoring can be helpful, as in the non-pregnant population.w15 Those women who have been defined as at increased risk of pre-eclampsia are monitored more closely, often in a specialised obstetric clinic. Part of the risk assessment includes Doppler ultrasound evaluation of the uterine arteries around the time of the fetal anomaly scan at 20–22 weeks (see below) and blood analysis (so called “PET bloods”—table 3). Rising blood pressure, deranged blood results, and/or the development of significant proteinuria requires enhanced surveillance. Greater than 1+ proteinuria on dip sticks needs to be formally quantified with a 24 hour urine collection or protein:creatinine ratios. The onset of significant proteinuria, in the absence of renal disease, is among the best indicators of superimposed pre-eclampsia. Depending on the severity of maternal symptoms and clinical findings and on the fetal growth pattern, a woman may be referred to a day assessment unit to permit regular outpatient review, or be admitted. Many women are initially asymptomatic, or present with non-specific signs of malaise. However, headache, visual disturbance, or abdominal pain are well recognised signs of severe pre-eclampsia (table 2).

Table 3.

Laboratory tests during pregnancy

| • Urinalysis: If >1+ proteinuria on dipstick arrange for 24 hour collection to quantify proteinuria |

| • Pre-eclampsia (“PET”) bloods: |

| - FBC: thrombocytopenia &/or haemoconcentration suggest severe pre-eclampsia |

| - U&Es: urea and creatinine are reduced in uncomplicated pregnancy, “normal” values may indicate renal impairment |

| - LFTs: transaminase concentrations increase in the HELLP syndrome (a variant of pre-eclampsia) |

| - Urate: levels are gestation related but rise in pre-eclampsia, largely due to reduced renal excretion |

| - Clotting screen: when the platelet count <100×109/l |

| - Blood film: microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia may occur in severe pre-eclampsia |

FBC, full blood count; HELLP, haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets; LFT, liver function test; U&E, urea and electrolytes.

Doppler assessment of uterine arteries

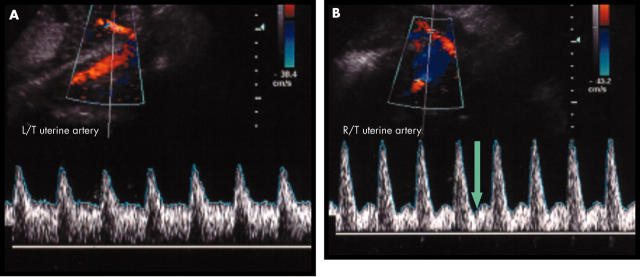

Pulsed wave and colour flow Doppler ultrasound examination of the uterine arteries can demonstrate the increased placental vascular resistancew16 which results from complete or partial failure of trophoblast invasion of the spiral arteries. In addition to a measurement of the resistance index, the presence of an abnormal uterine artery waveform is also sought (fig 1). Uterine artery “Dopplers” are offered to high risk women at between 20–24 weeks of pregnancy and have useful predictive power. A woman with normal uterine Doppler assessment at 20–24 weeks can be considered to be at low risk, whereas those with abnormal Dopplers have approximately a 20% chance of developing pre-eclampsia and require increased vigilance.w17

Figure 1.

Doppler uterine artery assessment showing (A) normal flow velocity waveform with low resistance, and (B) abnormal flow velocity waveform with an early diastolic notch (arrow) and a high resistance index.

Fetal surveillance

Women with both chronic hypertension and pre-eclampsia are at risk of IUGR. Such women are offered regular fetal ultrasound scans to assess fetal growth, liquor volume, and umbilical artery blood flow. When pre-eclampsia is severe, and there is a significant risk of delivery before 34 weeks gestation, intramuscular steroids (dexamethasone or betamethasone) are given to the mother to enhance fetal lung maturity in anticipation of a premature delivery.

WHEN TO TREAT HYPERTENSION DURING PREGNANCY

Significant hypertension must be treated in its own right, regardless of the assumed underlying pathology, largely to reduce the risk of maternal intracranial haemorrhage. The level at which antihypertensive treatment is initiated for non-severe hypertension remains controversial, depending on whether treatment is focused on maternal or fetal wellbeing.16,17 Most physicians commence antihypertensive medication when the systolic blood pressure > 140–170 mm Hg or diastolic pressure > 90–110 mm Hg. Treatment is mandatory for severe hypertension when the blood pressure is ⩾ 170/110 mm Hg. Once treatment is started, target blood pressure is also controversial, but many practitioners would treat to keep the mean arterial pressure < 125 mmHg—for example, a blood pressure 150/100 mm Hg. Overzealous blood pressure control may lead to placental hypoperfusion, as placental blood flow is not autoregulated, and this will compromise the fetus. Unfortunately there is no evidence that pharmacological treatment of chronic or gestational hypertension protects against the development of pre-eclampsia. Changes in diet or bed rest have not been shown to provide maternal or fetal benefit.w18–20

DRUG TREATMENT

All antihypertensive drugs have either been shown, or are assumed, to cross the placenta and reach the fetal circulation. However, as previously stated, none of the antihypertensive agents in routine use have been documented to be teratogenic, although ACE inhibitors and ARBs are fetotoxic. The objective of treating hypertension in pregnancy is to protect the woman from dangerously high blood pressure and to permit continuation of the pregnancy, fetal growth and maturation.

Mild to moderate hypertension

The evidence base for treatment of mild to moderate chronic hypertension in pregnancy resides in maternal benefit rather than clear evidence of an enhanced perinatal outcome for the baby.4 Some women with treated chronic hypertension are able to stop their medication in the first half of pregnancy, because of the physiological fall in blood pressure during this period. However, this is usually temporary, and women are monitored and treatment resumed as soon as necessary.

First line agent

Methyldopa

Methyldopa is a centrally acting agent and remains the drug of first choice for treating hypertension in pregnancy. It has been the most frequently assessed antihypertensive in randomised trials and has the longest safety track record. Long term use has not been associated with fetal or neonatal problems1 and there are safety data for children exposed in utero.18 Women should be warned of its sedative action and this can limit up titration. The drug may result in an elevation of liver transaminases (in up to 5% of women) or a positive Coomb’s test (although haemolytic anaemia is uncommon). Methyldopa should be avoided in women with a prior history of depression, because of the increased risk of postnatal depression.

Second line agents

These agents should be used when monotherapy with methyldopa is insufficient or when women are unable to tolerate methyldopa.

Nifedipine

Nifedipine is popular for the treatment of hypertension in pregnancy and is widely used. It is safe at any gestation.4 The use of sublingual nifedipine, however, should be avoided to minimise the risk of sudden maternal hypotension and fetal distress, caused by placental hypoperfusion. Abrupt hypotension is potentiated with concomitant magnesium sulfate (used as a treatment or prophylactic agent against eclamptic seizures with severe pre-eclampsia).w21 w22 Amlodipine has been used in pregnancy but safety data are lacking.5

Oral hydralazine

Hydralazine is safe throughout pregnancy, although the occurrence of maternal and neonatal lupus-like syndromes have been reported.19 Hydralazine is more frequently used as an infusion for the treatment of acute severe hypertension.

Third line agents

α and β Adrenergic blockers

In the past, β adrenergic blockers have been highlighted as a class of antihypertensives associated with an increased risk of IUGR.w23 Atenolol in particular has often been singled out. However, in a recent meta-analysis of published data from randomised trials, the presence of IUGR appeared not to be related to the antihypertensive used.16 Nevertheless, β adrenergic blockers are still avoided in the first half of pregnancy because of concerns about growth restriction and are viewed as third line agents for the treatment of hypertension in pregnancy. β Blockers are safe throughout pregnancy and there is wide experience with oxprenolol and labetalol. The safety and efficacy of prazosin in pregnancy has been demonstrated.w24 Doxazosin appears to be safe, although data are limited.

Thiazide diuretics

Thiazide diuretics are used infrequently in pregnancy. The drugs do not appear to be teratogenic19 and although such drugs abbreviate the plasma volume expansion associated with normal pregnancy,w25 this has not been proven to impair fetal growth.w26 The obstetric community remains reluctant to use these antihypertensive agents because of concern about potentiating the plasma volume contraction, which occurs with pre-eclampsia. However, women with chronic hypertension who, before conception, responded well to a thiazide diuretic, could have the drug reinstituted in pregnancy but it should be withdrawn if pre-eclampsia develops.w27

Drug treatment of severe hypertension

The mortality and morbidity of women with severe hypertension (> 170/110 mm Hg), usually secondary to severe pre-eclampsia, remain considerable. Because of the circulating plasma volume contraction, women may be very sensitive to relatively small doses of antihypertensive agents (and diuretics), risking abrupt reductions in blood pressure. Good control of hypertension in severe pre-eclampsia does not halt the progression of the disease, only delivery can do this, but it can reduce the incidence of complications such as cerebral haemorrhage. Management of severe hypertension involves adequate blood pressure control, often using parenteral agents, and “expectant” management by trying to prolong the pregnancy without unduly risking the mother or fetus. In severe cases, only hours or days may be gained. Different units have their preferences for either parenteral hydralazine or labetalol, and some use oral nifedipine. Hydralazine should be given after a colloid challenge to reduce the reflex tachycardia, and abrupt hypotension, precipitated by vasodilatation of a volume contracted circulation. These women are high risk and should be managed in a high dependency unit setting. They are very sensitive to fluid overload and are at risk of developing non-cardiac pulmonary oedema, through capillary leak.w28 Severe forms of pre-eclampsia require admission to intensive care, frequently for respiratory failure or the development of a severe systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).w29 Seizure prophylaxis, with intravenous magnesium sulfate, may be required in these cases.

ANTIHYPERTENSIVE DRUGS TO AVOID IN PREGNANCY

Both ACE inhibitors and ARBs are fetotoxic but there are no data to support teratogenicity.w30 w31 Women can thus be reassured that conceiving while taking such agents, particularly ACE inhibitors where the data are strongest, appears to be safe. However, all women of childbearing age treated with these drugs must be informed of the need for drug discontinuation within the first trimester should they become pregnant. The greatest risk to the fetus appears to be associated with exposure in the third trimester, but the earlier the discontinuation the better hence the need for patient education. A variety of malformations and adverse events have been reported for both ACE inhibitors and ARBs19w32 w33 including:

oligohydramnious

IUGR

joint contractures

pulmonary hypoplasia

hypocalvaria (incomplete ossification of the fetal skull)

fetal renal tubular dysplasia and neonatal renal failure.

ANTIHYPERTENSIVE TREATMENT POST PARTUM AND DURING BREASTFEEDING

Post partum hypertension is common. Blood pressure typically rises after delivery over the first five days.w1 Thus women who experienced hypertension during pregnancy may be normotensive immediately after the birth, but then become hypertensive again in the first postnatal week. The need to obtain hypertensive control may delay discharge. Methyldopa should be avoided post partum because of the risk of postnatal depression. Our first line agent is atenolol, plus nifedipine or an ACE inhibitor if another agent is required. Women with gestational hypertension, or pre-eclampsia, are usually able to stop all antihypertensives within six weeks post partum. Those with chronic hypertension can resume their pre-pregnancy drugs. Diuretics, however, are usually avoided if the woman wishes to breast feed because of increased thirst. Proteinuria in pre-eclamptic women will usually remit by three months post partum, in the absence of any underlying renal abnormality.w34 Persistent proteinuria requires further renal investigation.

Managing hypertension in pregnancy: key points.

Main categories of hypertensive disease in pregnancy: chronic, gestational, pre-eclampsia

Pre-eclampsia remains an important cause of maternal death in the UK

No antihypertensive has been shown to be teratogenic, but angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are fetotoxic

First line antihypertensive during pregnancy: methyldopa

First line antihypertensive post partum: atenolol

Pregnancy induced hypertension increases the risk of cerebrovascular disease and ischaemic heart disease in later life

An accurate estimation of drug passage into breast milk is difficult to individualise since it is influenced by many factors such as the lipid solubility of the drug, protein binding, ionisation, molecular weight, and the constituency of milk itself (fat, protein versus water content). However, most antihypertensive agents used in routine practice are compatible with breastfeeding,19,20 but safety data for doxazosin, amlodipine, and ARBs are lacking.

RISK OF RECURRENCE OF HYPERTENSIVE DISORDERS IN A SUBSEQUENT PREGNANCY

Women who experience hypertension in a first pregnancy are at increased risk in a subsequent pregnancy.21,22 Certain factors influence this risk. The earlier the onset of hypertension in the first pregnancy, the greater the risk of recurrence22w35 and the type of hypertensive disorder influences recurrence. One study reported a recurrence risk of 19% for gestational hypertension, 32% for pre-eclampsia, and 46% for pre-eclampsia superimposed on pre-existing chronic hypertension.22 In addition, severe isolated IUGR is also a risk factor for developing hypertension in a subsequent pregnancy.22w36

LONG TERM CARDIOVASCULAR SEQUELAE OF PREGNANCY INDUCED HYPERTENSION

Women who develop gestational hypertension or pre-eclampsia are at increased risk of hypertension and stroke in later adult life.23 Furthermore, there is evidence of an increased risk of ischaemic heart disease (IHD) in women who have experienced pre-eclampsia or isolated IUGR,24,25 together with increased death rates from IHD.26 At first an association between pre-eclampsia and an increased risk of IHD in later adult life may appear rather tenuous. However, both conditions are associated with dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance, and endothelial dysfunction.w37–40 It is of interest that the lipid abnormalities which occur in pre-eclampsia (raised low density lipoprotein (LDL), VLDL, free fatty acid, and triglyceride values) pre-date the clinical appearance of the conditionw39 w41 and endothelial dysfunction continues to be impaired post partum.27

Although there are methodological concerns with some of the data in this area, these apparent late sequelae may have important public health implications given the relative frequency of pregnancy induced hypertension and may, in future, dictate screening for cardiovascular disease in previously affected women. At the very least, it would seem prudent for such women to have an annual blood pressure measurement. Interestingly, women who go through a pregnancy without developing hypertension are at a reduced risk of becoming hypertensive in later life, when compared to nulliparous women.25 Pregnancy may offer a window into the future cardiovascular health of women, which is unavailable in men.28

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Sibai BM. Treatment of hypertension in pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1996;335:257–65. ▸ Excellent review article of the management of hypertension in pregnancy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shennan A, Gupta M, Halligan A, et al. Lack of reproducibility in pregnancy of Korotkoff phase IV measured by mercury sphygmomanometry. Lancet 1996;347:139–42. ▸ A well conducted trial evaluating the identification and reproducibility of Korotkoff sounds IV and V in pregnancy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown MA, Reiter L, Smith B, et al. Measuring blood pressure in pregnant women: a comparison of direct and indirect methods. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994;171:661–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magee LA, Ornstein MP, von Dadelszen P. Management of hypertension in pregnancy. BMJ 1999;318:1332–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown MA, Hague WM, Higgins J, et al. The detection, investigation and management of hypertension in pregnancy: full consensus statement. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2000;40:139–55. ▸ Good overview of pregnancy induced hypertension, including drug treatment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCowan LME, Buist RG, North RA, et al. Perinatal morbidity in chronic hypertension. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1996;103:123–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker JJ. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 2000;356:1260–5. ▸ A broad overview of the epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management of pre-eclampsia. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saudan P, Brown MA, Buddle ML, et al. Does gestational hypertension become pre-eclampsia? Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998;105:1177–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broughton Pipkin F. Risk factors for pre-eclampsia. N Engl J Med 2001;344:925–6. ▸ An excellent editorial on the multiple risk factors for developing pre-eclampsia. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Confidential enquiry into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom. Why mothers die. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2001. ▸ Death from cardiac disease is now the joint most common cause of maternal death in the UK. This latest report is highly informative.

- 11.Roberts J. Endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia. Semin Reprod Endocrinol 1998;16:5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts JM, Hubel CA. Is oxidative stress the link in the two-stage model of pre-eclampsia? Lancet 1999;354:788–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dekker GA, Sibai BM. Etiology and pathogenesis of preeclampsia: current concepts. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998;179:1359–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caritis S, Sibai BM, Hauth J, et al. Low-dose aspirin to prevent pre-eclampsia in women at risk. N Engl J Med 1998;338:701–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chappell LC, Seed PT, Briley AL, et al. Effects of antioxidants on the occurrence of pre-eclampsia in women at increased risk: a randomised trial. Lancet 1999;354:810–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Von Dadelszen P, Ornstein MP, Bull SB, et al. Fall in mean arterial pressure and fetal growth restriction in pregnancy hypertension: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2000;355:87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Homuth V, Dechend R, Luft FC. When should pregnant women with an elevated blood pressure be treated? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003;18:1456–7. ▸ An up to date evaluation of the evidence for treatment of hypertension in pregnancy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cockburn J, Moar VA, Ounsted M, et al. Final report of study on hypertension during pregnancy: the effects of specific treatment on the growth and development of the children. Lancet 1982;i:647–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Yaffe SJ. In Mitchell CW, ed. Drugs in pregnancy and lactation: a reference guide to fetal and neonatal risk. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2002. ▸ A comprehensive, up to date text, solely on the safety of drugs in pregnancy and breastfeeding.

- 20.Committee on Drugs, American Academy of Pediatrics. The transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics 1994;93:137–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hargood JL, Brown MA. Pregnancy-induced hypertension; recurrence rate in second pregnancies. Med J Austral 1991;154:376–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Troendle JF, Levine RJ. Risks of hypertensive disorders in the second pregnancy. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2001;15:226–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson BJ, Watson MS, Prescott GJ, et al. Hypertensive diseases of pregnancy and risk of hypertension and stroke in later life: results from cohort study. BMJ 2003;326:845–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith GCS, Pell JP, Walsh D. Pregnancy complications and maternal complications of ischaemic heart disease: a retrospective cohort study of 129 290 births. Lancet 2001;357:2002–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hannaford P, Ferry S, Hirsh S. Cardiovascular sequelae of toxaemia of pregnancy. Heart 1997;77:154–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jonsdottir LS, Arnsgrimsson R, Geirsson RT, et al. Death rates from ischemic heart disease in women with a history of hypertension in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1995;74:772–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chambers JC, Fusi L, Malik IS, et al. Association of maternal endothelial dysfunction with preeclampsia. JAMA 2001;258:1607–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seely EW. Hypertension in pregnancy: a potential window into long-term cardiovascular risk in women. Clin Endo Metab 1999;84:1858–61. ▸ An overview of possible mechanisms involved in the increased cardiovascular risk in women with a prior history of pregnancy induced hypertension. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.