In 2000, the European Society of Cardiology and the American College of Cardiology presented new diagnostic criteria for myocardial infarction (MI) which placed a greater emphasis on cardiac markers by stating that any elevation in cardiac troponin T (cTnT) or cardiac troponin I (cTnI) above the 99th centile of normal was sufficient to diagnose a MI.1 Recent studies since then have shown that the wholesale adoption of these new criteria would lead to a substantial increase in MI incidence.2

As a separate issue, it has been repeatedly shown that women diagnosed as having had an MI tend to be managed less aggressively and have a poorer prognosis compared to men. However, since women tend to present when they are older it has been disputed that age rather than sex bias may be the reason.3

This study therefore aimed to establish the extent to which the new criteria for MI were being applied to patients admitted to a busy UK teaching hospital and to determine whether any age or sex bias may exist when making this diagnosis.

METHODS

Six thousand one hundred and seventy two samples of cTnT were collected during 5343 non-elective admissions on 4828 patients; 2505 were men, median age 66 years, interquartile range (IQR) 54–78 years, 2323 were women, median age 74 years, IQR 63–84 years, attending Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust in 2002. These figures excluded patients with heart failure, pulmonary embolism, or with the likelihood of significant renal impairment (creatinine > 200 μmol/l). The cTnT values were compared with the International classification of disease (ICD) 10 discharge diagnosis recorded by the trust. Local policy recommended a single cTnT measurement 12 hours after the onset of chest pain, but if patients had multiple cTnT requests on the same admission, the highest result was used. A cTnT value > 0.05 μg/l was regarded as indicating significant myocardial damage. The troponin service in the hospital was exclusively limited to acute admissions with non-traumatic chest pain.

Before the introduction of the cTnT service in October 2001, the diagnosis of MI was based on the World Health Organization criteria4 of persistent chest pain, ECG changes and/or a rise in cardiac markers which, in Hull, was using creatine kinase (CK) and CK-MB.

RESULTS

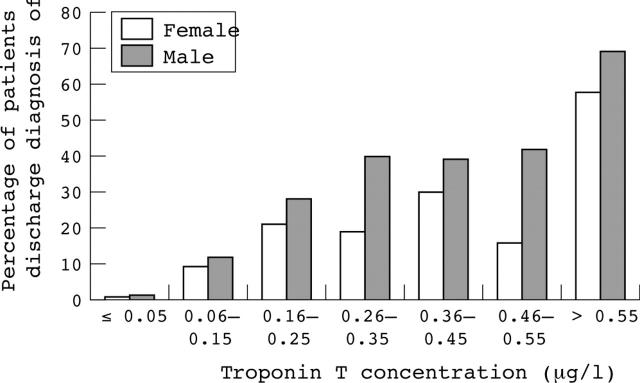

Of 561 recorded MIs during 2002 in patients with a full dataset, 521 (93%) had raised cTnT values. However, only 521/1304 (40%) of admissions with raised cTnT concentrations were discharged with a MI diagnosis. Furthermore, this comprised 326/713 (46%) of males and just 197/591 (33%) of females (χ2 = 20.14, p < 0.0001) (fig 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of male and female patients discharged with a diagnosis of myocardial infarction according to cardiac troponin T value.

Multiple logistic regression showed sex to still be a separate predictor of MI diagnosis (female v male odds ratio 0.61, p < 0.0001) but patient age not so (p = 0.10), independently of a raised cTnT value (p < 0.0001).

Of the 40 patients without raised cTnT values but an MI diagnosis, 14 had a detectable but ⩽ 0.05 μg/l cTnT rise, eight patients developed ECG changes (although not usually classical) during their admission, seven patients were incorrectly coded as having had an MI, four patients had suffered an MI during their admission, three patients were transferred from other hospitals long after their MI, in two patients it appeared the cTnT sample had been taken too early, while in one the diagnosis of MI on the discharge letter seemed incorrect, and in one other the set of notes could not be traced.

DISCUSSION

In the hospital studied, the anticipated rise in MI incidence because of the new diagnostic criteria has yet to be fully realised since the majority of patients (60%) with raised cTnT values were not recorded as having had an infarct; this is despite a full calendar year having elapsed between the guidelines being published and the start of this study. Variation in the adoption of these criteria between centres is likely to lead to inconsistencies in the way many patients are treated or subsequently investigated, and may also result in inaccurate comparisons in clinical care standards between hospitals.5

Until now, sex bias has only been identified in the management of females after a diagnosis of MI has already been made. This study has now provided the first evidence that women seem less likely to be diagnosed with an MI in the first place, despite a raised cTnT value being a completely objective finding available to the clinician.

The reasons for this bias must remain speculative. However, from this data, the finding appears to be independent of the older age at which the females were affected. Thus, other factors, such as the perception that women have a lower pre-test probability of infarction, must influence the clinician’s discharge decision.

In conclusion, this study has shown that the new diagnostic criteria for MI are not being applied methodically in the hospital studied, and that males with raised cTnT values are more likely to be discharged as having had an MI than females. Since we know that cTnT is at least as useful a prognostic indicator in women as in men,6 this lack of systematic use of new criteria appears to disadvantage females more than males.

REFERENCES

- 1.European Society of Cardiology, American College of Cardiology. Myocardial infarction redefined—a consensus document of the joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2000;21:1502–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pell JP, Simpson E, Rodger JC, et al. Impact of changing diagnostic criteria on incidence, management, and outcome of acute myocardial infarction: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2003;326:134–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams JN, Jamieson M, Rawles JM, et al. Women and myocardial infarction: agism rather than sexism? Br Heart J 1995;73:87–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization Expert Committee. Hypertension and coronary heart disease: classification and criteria for epidemiological studies. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1959, (Technical Report Series No 168.). [PubMed]

- 5.Pell ACH, Pell JP. Variations in access to and interpretation of troponin assays are wide. BMJ 2002;324:1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safstrom K, Lindahl B, Swahn E. Risk stratification in unstable coronary artery disease—exercise test and troponin T from a gender perspective. FRISC study Group. Fragmin during instability in coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:1791–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]