Abstract

Objective: To evaluate how well patients with non-valvar atrial fibrillation (NVAF) were maintained within the recommended international normalised ratio (INR) target of 2.0–3.0 and to explore the relation between achieved INR control and clinical outcomes.

Design: Record linkage study of routine activity records and INR measurements.

Setting: Cardiff and the Vale of Glamorgan, South Wales, UK.

Participants: 2223 patients with NVAF, no history of heart valve replacement, and with at least five INR measurements.

Main outcome measures: Mortality, ischaemic stroke, all thromboembolic events, bleeding events, hospitalisation, and patterns of INR monitoring.

Results: Patients treated with warfarin were outside the INR target range 32.1% of the time, with 15.4% INR values > 3.0 and 16.7% INR values < 2.0. However, the quartile with worst control spent 71.6% of their time out of target range compared with only 16.3% out of range in the best controlled quartile. The median period between INR tests was 16 days. Time spent outside the target range decreased as the duration of INR monitoring increased, from 52% in the first three months of monitoring to 30% after two years. A multivariate logistic regression model showed that a 10% increase in time out of range was associated with an increased risk of mortality (odds ratio (OR) 1.29, p < 0.001) and of an ischaemic stroke (OR 1.10, p = 0.006) and other thromboembolic events (OR 1.12, p < 0.001). The rate of hospitalisation was higher when INR was outside the target range.

Conclusions: Suboptimal anticoagulation was associated with poor clinical outcomes, even in a well controlled population. However, good control was difficult to achieve and maintain. New measures are needed to improve maintenance anticoagulation in patients with NVAF.

It has been estimated that 470 000 patients received oral anticoagulation in 2001 in the UK.1 This number is likely to increase as the number of people in the elderly population increases.2 Furthermore, there are plans to identify all patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) through primary care screening as part of a national stroke prevention strategy implemented in 2004.3

Long term anticoagulation treatment of patients with non-valvar atrial fibrillation (NVAF) can reduce the annual risk of stroke by two thirds.4,5 Such treatment compares favourably with the alternative, aspirin treatment.6 However, the pharmacokinetic profile of warfarin is complex,7 and monitoring is required to avoid both thromboembolic events associated with low intensity anticoagulation and haemorrhagic complications associated with higher intensity. Target levels of oral anticoagulation are disease specific and measured with the international normalised ratio (INR). In the case of NVAF, the range is 2.0–3.0. To attain INR values within this range, patients are routinely monitored and their doses are adjusted when necessary. In practice, it is recognised that long term stability is difficult to achieve because of unexpected fluctuations of the INR values in patients, which can be attributed to numerous factors including change in diet, poor compliance with medication, alcohol consumption, seasonal variation, and drug to drug interactions.7–9

The objective of the study was to evaluate how well patients with NVAF were maintained within the recommended INR target of 2.0–3.0 and to explore the relation between achieved INR control and clinical outcome.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

Data sources

Three sets of data routinely collected in the UK were used: inpatient data from April 1995 to March 2000 containing a range of information including discharge diagnosis (International classification of diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10)), length of stay and operative procedures (Office of Population, Censuses and Surveys); haematology laboratory reports dating from June 1995 to January 2002 containing details of INR monitoring test results (including any initiated by a primary care source); and mortality data derived from the UK Office of National Statistics from January 1995 containing information on cause of death (ICD-9). These data underwent a process of record linkage to identify those records relating to the same patient both within and between the contributory datasets by using probability matching algorithms.10 The epidemiology of stroke11 and heart disease12 has been described previously in this same population with virtually identical methods.

Participants

The study was conducted in Cardiff and the Vale of Glamorgan, a largely urban area of South Wales with a population of 424 000 (2001 census). Patients were those identified during the period with a diagnosis of AF (ICD-10 code I48) recorded on inpatient admission and a minimum of five INR recordings before and after their initial NVAF admission. These patients were assumed to be taking oral anticoagulation in the form of warfarin, although no direct data on drugs or dosage were available. Patients were excluded if they had any record of heart valve procedures (appendix 1) before the first recorded AF diagnosis because the target INR range is higher for this indication.7

Linear interpolation and target range

To estimate the proportion of time that a patient was within the normal range, we assumed that the actual difference in INR between any two consecutive measurements was linear, and the data were interpolated accordingly.13 Time in target range for each patient was assessed by the percentage of interpolated INR values within the target range of 2.0–3.0.

Statistical analyses

The patterns of INR testing were analysed by calculating the time in days between consecutive INR tests for each patient. The relation between the intensity of INR and duration of warfarin treatment was investigated by plotting the average percentage of time in range versus the time in months after initial warfarin treatment. Patients who had an INR reading within six weeks of the earliest available data were omitted from this analysis, as it was not possible to determine whether an INR value was a first reading or a subsequent reading.

Multivariate logistic regression was applied to the data to assess whether poor control was associated with mortality and post-AF clinical events—namely, bleeding, thromboembolic events, and ischaemic stroke (appendix 2). All the models included age, sex, and hospital length of stay at first recorded AF admission (an indicator of morbidity at baseline), with the models for clinical events including a term for any pre-AF occurrences of the event. Regression models were then constructed through the individual inclusion of terms relating to different aspects of INR control. The mean INR and the standard deviation of INR terms were related to the raw INR data, with the odds ratios constructed for 0.1 unit changes in INR. We constructed odds ratios for the percentage time in and out of range variables where there was a 10% change in the variable of interest.

RESULTS

From the 222 398 patients hospitalised during the study period we identified 6247 patients with AF and excluded 139 (2.2%) on the basis of a history of heart valve surgery. The remainder, 6108, had NVAF; of these patients, 2828 (46.3%) had any INR reading and 2223 (36.4%) had more than four INR readings. These 2223 patients constituted the study group, for whom there were 135 149 actual INR readings and 2 118 881 follow up days for which values were calculated. This group had a crude population prevalence of 0.53% and an age specific prevalence of 4.5% in those older than 75 years; 53.1% were men with a mean (SD) age of 69.8 (11.0) years at the time of the first recorded AF event (table 1). The corresponding mean (SD) age for women was 75.6 (9.0) years. No clear relation was evident between age at first recorded AF diagnosis and mean INR; however, average length of hospital stay and the proportion of deaths within three months of the first recorded AF event increased noticeably with increasing age (table 1).

Table 1.

Key summary statistics for the non-valvar atrial fibrillation (AF) study group

| Sex | Age group (years) | Number of patients | Mean INR | Mean LOS (days) | Death* (%) | Emergency readmission† (%) |

| Men | <60 | 171 | 2.5 | 8.0 | 1.8 | 5.8 |

| 60–64 | 150 | 2.5 | 9.2 | 4.7 | 5.3 | |

| 65–70 | 242 | 2.5 | 8.2 | 3.7 | 5.0 | |

| 71–75 | 240 | 2.5 | 10.3 | 4.2 | 5.8 | |

| >75 | 376 | 2.5 | 12.4 | 9.0 | 3.5 | |

| All ages | 1179 | 2.5 | 10.1 | 5.3 | 4.8 | |

| Women | <60 | 57 | 2.6 | 7.6 | 0.0 | 8.8 |

| 60–64 | 53 | 2.7 | 7.3 | 1.9 | 7.5 | |

| 65–70 | 138 | 2.6 | 10.3 | 5.1 | 5.8 | |

| 71–75 | 217 | 2.6 | 11.2 | 5.5 | 6.5 | |

| >75 | 578 | 2.6 | 15.2 | 8.1 | 4.0 | |

| All ages | 1043 | 2.6 | 12.9 | 6.4 | 5.2 |

*Death within three months of the first recorded AF event.

†Return as inpatients with an emergency admission code within a week of the first recorded AF event.

INR, international normalised ratio; LOS, length of hospital stay at the time of the first recorded AF.

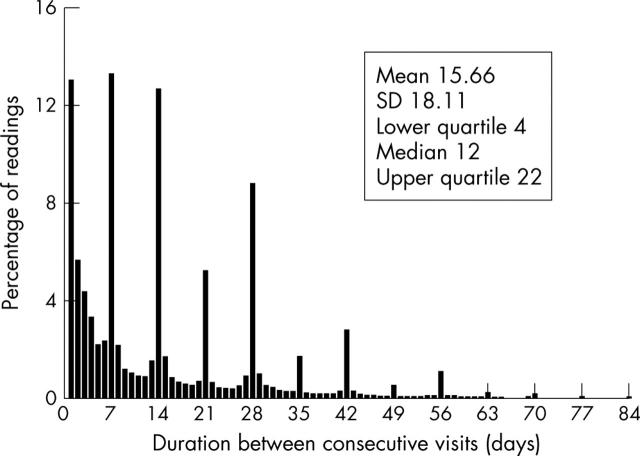

There was a clear pattern of consecutive clinic visits occurring either weekly (13.3%), bi-weekly (12.7%), or monthly (8.8%) (fig 1). The mean (SD) time between consecutive visits was 15.7 (18.1 days), with a median of 12 days and an interquartile range of 4–22 days. Of the 137 507 INR measurements, 46.6% were outside the target range.

Figure 1.

Percentage of international normalised ratio (INR) readings versus time between consecutive INR readings.

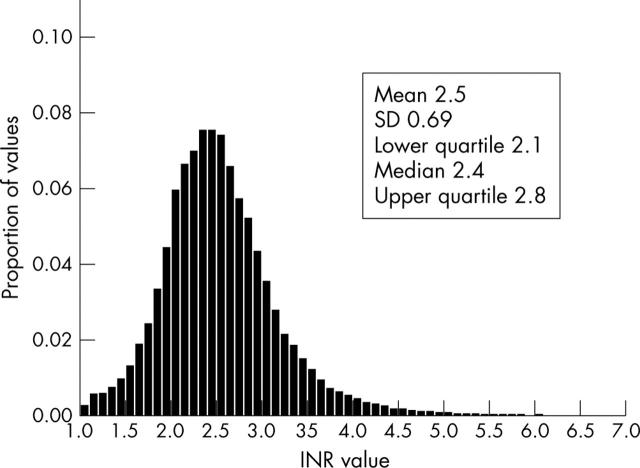

In a plot of interpolated INR values, the distribution of INR intensity is asymmetrical and positively skewed (fig 2). Under these conditions, the mean (SD) INR value was 2.5 (0.69), with a median of 2.4 and an interquartile range of 2.4–2.8. In a plot of interpolated data, patients were outside the target range 32.1% of the time, with 15.4% of INR values > 3.0 and 16.7% of INR values < 2.0. However, division of the patients into quartiles based on proportion of time spent in target range highlighted that these average figures disguised a wide variation in the time spent out of target range. On average, patients in the quartile with worst control were out of target range for 71.6% of the time, as compared with 16.3% in the best controlled quartile.

Figure 2.

Distribution of interpolated INR values.

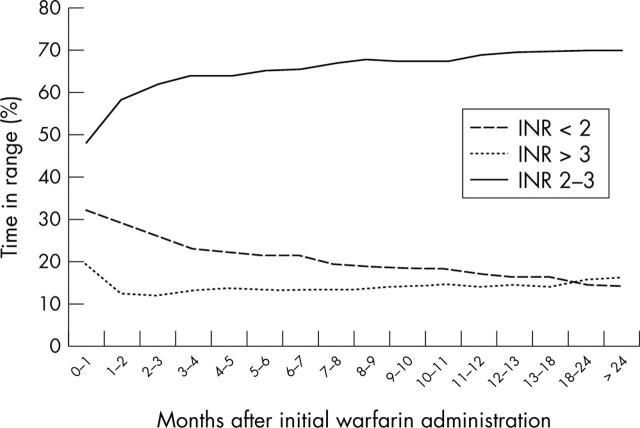

Figure 3 shows the relation between the proportion of results within, above, and below the desired INR range of 2.0–3.0 by duration of treatment. The proportion of INR results outside the desired target range decreased as the duration of warfarin treatment increased, ranging from 52% outside the target range in the first month and decreasing to 30% after two years of monitoring.

Figure 3.

Interpolated INR values in target range (2–3) versus time after start of warfarin treatment.

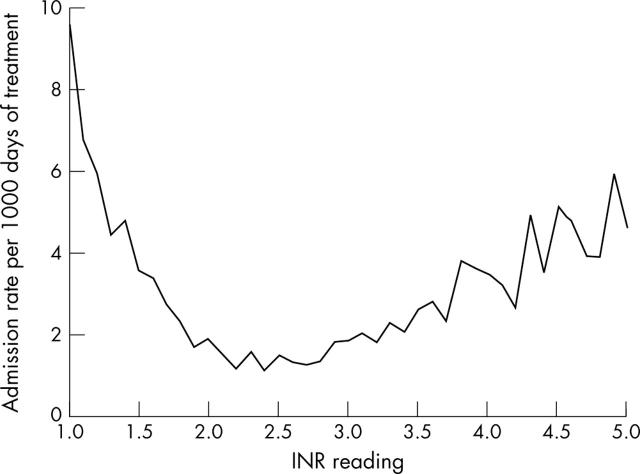

There were 5350 hospital admissions for patients from the study group after the initial admission with a diagnosis of NVAF. The rate of hospitalisation increased the further the INR value deviated from the target range (fig 4). The rates of admission were lowest when the INR value for the day before admission was towards the midpoint of the target range.

Figure 4.

Hospital admission rate as a function of INR level.

Multivariate logistic regression models showed that an increased risk of all cause mortality, ischaemic stroke, and all post-AF thromboembolic events was associated with poor warfarin control measured in various ways (table 2) after adjustment for age, sex, and morbidity at baseline. For example, a 10% increase in the time out of range was associated with an increase in the risk of mortality of 29% (odds ratio (OR) 1.29, p < 0.001), an increase of 10% in the risk of an ischaemic stroke (OR 1.15, p = 0.006), and an increase of 12% for all thromboembolic events (OR 1.12, p < 0.001). The risk of an admission for a bleeding related event was also associated with a prior bleeding event and with greater variability in INR values as measured by the standard deviation of the INR readings (OR 1.04, p = 0.017).

Table 2.

Logistic regression models evaluating the relation between post-AF clinical outcomes and anticoagulation control

| Variable | All cause mortality | Bleeding events | Thromboembolic events | Ischaemic strokes | ||||

| OR(75% CI) | p Value | OR(75% CI) | p Value | OR(75% CI) | p Value | OR(75% CI) | p Value | |

| Age | 1.057(1.045 to 1.070) | 0.000* | 1.029(1.008 to 1.051) | 0.017* | 1.026(1.012 to 1.040) | 0.000* | 1.020(1.003 to 1.037) | 0.001* |

| Sex | 0.842(0.689 to 1.029) | 0.158 | 0.593(0.394 to 0.893) | 0.008* | 0.976(0.754 to 1.263) | 0.882 | 1.071(0.780 to 1.470) | 0.727 |

| Length of stay | 1.015(1.009 to 1.021) | 0.000* | 1.007(0.996 to 1.017) | 0.262 | 1.008(1.001 to 1.015) | 0.036* | 1.012(1.004 to 1.019) | 0.003* |

| Pre-AF bleeding | NA | NA | 2.571(1.186 to 5.573) | 0.031* | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Pre-AF thromboembolic event | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.501(1.017 to 2.214) | 0.048* | NA | NA |

| Pre-AF stroke | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3.397(2.063 to 5.594) | 0.000* |

| + Mean INR† | 1.049(1.025 to 1.073) | 0.000* | 1.017(0.974 to 1.061) | 0.460 | 0.955(0.924 to 0.987) | 0.004* | 0.942(0.904 to 0.982) | 0.003* |

| + SD INR† | 1.087(1.064 to 1.110) | 0.000* | 1.040(1.010 to 1.072) | 0.017* | 1.004(0.980 to 1.029) | 0.747 | 1.002(0.973 to 1.033) | 0.879 |

| + % in target range‡ | 0.774(0.738 to 0.811) | 0.000* | 0.945(0.865 to 1.033) | 0.218 | 0.891(0.842 to 0.942) | 0.000* | 0.905(0.844 to 0.970) | 0.006* |

| + % irregular (<2.0)‡ | 1.172(1.119 to 1.228) | 0.000* | 1.008(0.917 to 1.107) | 0.876 | 1.148(1.088 to 1.212) | 0.000* | 1.146(1.074 to 1.223) | 0.000* |

| + % irregular (>3.0)‡ | 1.217(1.143 to 1.296) | 0.000* | 1.097(0.977 to 1.232) | 0.134 | 0.948(0.867 to 1.036) | 0.229 | 0.903(0.802 to 1.017) | 0.079 |

| + % out of target range‡ | 1.293(1.233 to 1.355) | 0.000* | 1.058(0.968 to 1.156) | 0.218 | 1.123(1.061 to 1.188) | 0.000* | 1.105(1.031 to 1.184) | 0.006* |

*Significant at the 5% level; †0.1 unit change in the actual INR value; ‡10% change in specified range.

CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

DISCUSSION

In the general population, only a minority of patients with NVAF were treated with warfarin, despite its proven efficacy in reducing stroke and other vascular events. There are conflicting guidelines about the use of anticoagulant treatment.14 For many patients—for example, those under 65 years without any other complicating factors such as diabetes, hypertension, or previous cerebrovascular event—warfarin treatment is not considered necessary.15 In addition, there are practical barriers to safe warfarin treatment such as the need for constant monitoring of INR values, individual risk of haemorrhage, and patient preferences.16

Within the group of patients who were routinely monitored with INR readings—assumed to result from warfarin treatment—almost a third of the treatment time and close to half of the raw INR readings were outside the target range. Even so, this result was rather low compared with those found in other published data,17,18 possibly reflecting that the centre where this study took place is a university teaching hospital. Patients treated in other, non-academic settings may not achieve this level of control. The quality of care may also relate to the frequency of testing. The patients in our population had INR tests 23 times a year on average, whereas monitoring rates as high as 13 times within three months and as low as six times over a year have been reported.19,20 The frequency of testing appears to depend on the local model of anticoagulation and, in addition to the quality of control provided, has direct consequences on the cost of AF management.21

The overall figure for the study group also conceals wide variation in the actual time spent in range by any individual patient. The quartile of patients with the poorest control spent, on average, almost three times as long out of range as the group with the best control. Patients were least likely to die or be admitted to hospital when their INR values were near to the midpoint of the target range. Although, in view of the influence of illness and changes in medication, it would be overly simplistic to assume a direct relation between a point INR result and overall outcomes, this may tend to confirm the target range as the optimal level of anticoagulation in NVAF.

Because of the inherent difficulty in maintaining control at the individual level, characterising what we mean by poor control in these patients was in itself difficult from a mathematical perspective. We investigated measurement of poor control through a number of alternative parameters in multivariate analysis, standardising for age, sex, and baseline morbidity. All of the selected measurements were associated with poor outcome.

Even in this group of patients, who at a population level appear to have good control, instability of INR values has significant implications for mortality and other clinical outcomes. We have shown an association between INR values outside the target range and increased rate of hospitalisation. In addition we have shown that a 10% increase in the amount of time out of range is associated with an increase in the likelihood of death of 29.3% and increased the probability of a thromboembolic event by 12.4%, confirming previous findings.1,2 Since INR control was worst during the first three months after the initiation of warfarin and poor control was linked to an increased risk of events, it was likely that patients were at higher risk of events during their first months of treatment while an appropriate dose of warfarin was being established. However, some patients were anticoagulated after an index stroke event, which in itself predicts future stroke events.13 The improvements in time spent in range that occur over time may in part be caused by the withdrawal from treatment of patients who have the greatest difficulty with warfarin treatment, either in control or adverse events.

There were limitations to this study. No data were available describing medication including warfarin or warfarin dosage. Because of this we assumed that only patients who had some degree of continuous monitoring (> 4 INR observations) were treated with warfarin. We were unable to control for confounding factors including other medications and co-morbidities where that information was primarily held in primary care records. The lack of primary care health records also prevented us stratifying patients by their underlying risk of stroke, although it has been calculated that as few as 6% of patients with AF are at low risk of stroke.22 Furthermore, only patients who had an inpatient diagnosis of NVAF were included. Patients with AF diagnosed in primary care could not be identified; therefore, the patients included in the study may have greater morbidity than a sample selected from both the hospital and community. There are also methodological issues when attempting to estimate the proportion of time a patient is within or outside the target INR range.1 The assumption that INR values change in a linear fashion is unlikely to be the case. Values may change sharply soon after a reading has been taken as a result of treatment management or before a reading that has been initiated by a clinical event. As a result extreme values of INR may lead to a bias, as the time spent at either extreme is overestimated. However, the proportion of measurements at these extreme values would be small13 and linear interpolation has been shown to be the simplest and most valid technique compared with other methods.23 Given these limitations, these data describe the care and monitoring of a large cohort of patients, with a very large number of INR values over a lengthy study period.

To conclude, suboptimal anticoagulation was associated with poor clinical outcomes; however, good control is difficult to achieve and maintain. New measures are needed to improve maintenance anticoagulation in patients with NVAF.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by AstraZeneca UK.

Abbreviations

AF, atrial fibrillation

ICD, International classification of diseases

INR, international normalised ratio

NVAF, non-valvar atrial fibrillation

APPENDIX 1

Table ta1.

Office of Population, Censuses and Surveys (OPCS) codes used to identify the heart valve procedures in the study

| OPCS code | Description |

| Heart valve procedures | |

| K25 | Plastic repair of mitral valve |

| K26 | Plastic repair of aortic valve |

| K27 | Plastic repair of tricuspid valve |

| K28 | Plastic repair of pulmonary valve |

| K29 | Plastic repair of unspecified valve of heart |

| K30 | Revision of plastic repair of valve of heart |

| K31 | Open incision of valve of heart |

| K32 | Closed incision of valve of heart |

| K34 | Other open operations on valve of heart |

| K35 | Therapeutic transluminal operations on valve of heart |

| K37 | Removal/obstruction from structure adjacent/valve heart |

| K38 | Other operations on structure adjacent to valve of heart |

APPENDIX 2

Table ta2.

International classification of diseases, 10 revision (ICD-10) codes used to identify the serious adverse events in this study

| ICD-10 code | Description |

| Myocardial infarction | |

| I210 | Acute transmural myocardial infarction of anterior wall |

| I211 | Acute transmural myocardial infarction of inferior wall |

| I212 | Acute transmural myocardial infarction of other sites |

| I213 | Acute transmural myocardial infarction of unspecified site |

| I214 | Acute subendocardial myocardial infarction |

| I219 | Acute myocardial infarction, unspecified |

| I220 | Subsequent myocardial infarction of anterior wall |

| I221 | Subsequent myocardial infarction of inferior wall |

| I228 | Subsequent myocardial infarction of other sites |

| I229 | Subsequent myocardial infarction of unspecified site |

| Deep vein thrombosis | |

| I802 | Phlebitis/thrombophlebitis of other deep vessels low extremities |

| Pulmonary embolism | |

| I260 | Pulmonary embolism with mention of acute cor pulmonale |

| I269 | Pulmonary embolism without mention of acute cor pulmonale |

| Bleeding | |

| K226 | Gastro-oesophageal laceration-haemorrhage syndrome (Mallory-Weiss syndrome) |

| K250 | Gastric ulcer, acute with haemorrhage |

| K252 | Gastric ulcer, acute with both haemorrhage and perforation |

| K254 | Gastric ulcer, chronic or unspecified with haemorrhage |

| K260 | Duodenal ulcer, acute with haemorrhage |

| K262 | Duodenal ulcer, acute with both haemorrhage and perforation |

| K264 | Duodenal ulcer, chronic or unspecified with haemorrhage |

| K270 | Peptic ulcer, acute with haemorrhage |

| K272 | Peptic ulcer, acute with both haemorrhage and perforation |

| K274 | Peptic ulcer, chronic or unspecified with haemorrhage |

| K280 | Gastrojejunal ulcer, acute with haemorrhage |

| K284 | Gastrojejunal ulcer, chronic or unspecified with haemorrhage |

| K922 | Gastrointestinal haemorrhage, unspecified |

| M250 | Haemarthrosis |

| R040 | Epistaxis |

| R041 | Haemorrhage from throat |

| R042 | Haemoptysis |

| R048 | Haemorrhage from other sites in respiratory passages |

| R049 | Haemorrhage from respiratory passages, unspecified |

| R58X | Haemorrhage, not elsewhere classified |

| T792 | Traumatic secondary and recurrent haemorrhage |

| N026 | Recurrent and persistent haematuria, dense deposit disease |

| N028 | Recurrent and persistent haematuria, other |

| N029 | Recurrent and persistent haematuria, unspecified |

| R31X | Unspecified haematuria |

| I610 | Intracerebral haemorrhage in hemisphere, subcortical |

| I611 | Intracerebral haemorrhage in hemisphere, cortical |

| I612 | Intracerebral haemorrhage in hemisphere, unspecified |

| I613 | Intracerebral haemorrhage in brain stem |

| I614 | Intracerebral haemorrhage in cerebellum |

| I615 | Intracerebral haemorrhage, intraventricular |

| I616 | Intracerebral haemorrhage, multiple localised |

| I618 | Other intracerebral haemorrhage |

| I619 | Intracerebral haemorrhage, unspecified |

| I620 | Subdural haemorrhage (acute) (non-traumatic) |

| I621 | Non-traumatic extradural haemorrhage |

| I629 | Intracranial haemorrhage (non-traumatic), unspecified |

| Stroke | |

| G450 | Vertebrobasilar artery syndrome |

| G451 | Carotid artery syndrome (hemispheric) |

| G452 | Multiple and bilateral precerebral artery syndromes |

| G453 | Amaurosis fugax |

| G454 | Transient global amnesia |

| G458 | Other transient cerebral ischaemic attacks and related syndromes |

| G459 | Transient cerebral ischaemic attack, unspecified |

| G460A | Middle cerebral artery syndrome |

| G461A | Anterior cerebral artery syndrome |

| G462A | Posterior cerebral artery syndrome |

| G463A | Brain stem stroke syndrome |

| G464A | Cerebellar stroke syndrome |

| G465A | Pure motor lacunar syndrome |

| G466A | Pure sensory lacunar syndrome |

| G467A | Other lacunar syndromes |

| G468A | Other vascular syndromes of brain in cerebrovascular diseases |

| I630 | Cerebral infarction due to thrombosis of precerebral arteries |

| I631 | Cerebral infarction due to embolism of precerebral arteries |

| I632 | Cerebral infarction due to unspecified occlusion or stenosis of precerebral arteries |

| I633 | Cerebral infarction due to thrombosis of cerebral arteries |

| I634 | Cerebral infarction due to embolism of cerebral arteries |

| I635 | Cerebral infarction due to unspecified occlusion or stenosis of cerebral arteries |

| I636 | Cerebral infarction due to cerebral venous thrombosis, non-pyogenic |

| I638 | Other cerebral infarction |

| I639 | Cerebral infarction, unspecified |

| I64X | Stroke, not specified as haemorrhage or infarction |

| I650 | Occlusion and stenosis of vertebral artery |

| I651 | Occlusion and stenosis of basilar artery |

| I652 | Occlusion and stenosis of carotid artery |

| I653 | Occlusion and stenosis of multiple and bilateral precerebral arteries |

| I658 | Occlusion and stenosis of other precerebral artery |

| I659 | Occlusion and stenosis of unspecified precerebral artery |

| I660 | Occlusion and stenosis of middle cerebral artery |

| I661 | Occlusion and stenosis of anterior cerebral artery |

| I662 | Occlusion and stenosis of posterior cerebral artery |

| I663 | Occlusion and stenosis of cerebellar arteries |

| I664 | Occlusion and stenosis of multiple and bilateral cerebral arteries |

| I668 | Occlusion and stenosis of other cerebral artery |

| I669 | Occlusion and stenosis of unspecified cerebral artery |

| I678 | Other specified cerebrovascular diseases |

| I688A | Other cerebrovascular disorders in diseases classified elsewhere |

| I693 | Sequelae of cerebral infarction |

Although all of the authors have academic appointments, this work was commissioned in their university spinout company, Cardiff Research Consortium Limited. CRC undertakes applied research for the pharma industry and has worked for a wide range of companies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fitzmaurice DA, Machin SJ. Recommendations for patients undertaking self management of oral anticoagulation. BMJ 2001;323:985–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chatap G, Giraud K, Vincent JP. Atrial fibrillation in the elderly: facts and management. Drugs Aging 2002;19:819–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health. National framework for older people. Standard 5: stroke. London: Stationery Office, 2001.

- 4.EAFT Study Group. Secondary prevention in non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation after transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke. EAFT (European atrial fibrillation trial) Study Group. Lancet 1993;342:1255–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Risk factors for stroke and efficacy of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation: analysis of pooled data from five randomised controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:1449–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Walraven C, Gart RG, Singer DE, et al. Oral anticoagulants vs. aspirin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: an individual patient meta-analysis. JAMA 2002;288:2441–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirsh J, Fuster V, Ansell J, et al. American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation guide to anticoagulation therapy. Circulation 2003;107:1692–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hylek EM, et al. Acetaminophen and other risk factors for excessive warfarin anticoagulation. JAMA 1998;279:657–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salobir B, Sabovic M, Peternel P. Intensity of long-term treatment with warfarin is influenced by seasonal variations. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb 2002;32:151–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gill L, Goldacre M, Simmons H, et al. Computerised linking of medical records: methodological guidelines. J Epidemiol Commun Health 1993;47:316–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Currie CJ, Morgan CL, Gill L, et al. The epidemiology and costs of acute hospital care for cerebrovascular disease in diabetic and non-diabetic populations. Stroke 1997;28:1142–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Currie CJ, Morgan CL, Peters JR. Patterns and costs hospital care for coronary heart disease relate and not related to diabetes. Heart 1997;78:544–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, van der Meer FJM, et al. A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thomb Haemost 1993;69:236–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomson R, McElroy, Sudlow M. Guidelines on the anticoagulant treatment in atrial fibrillation in Great Britain: variation in content and implication s for treatment. BMJ 1998;316:509–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lip GYH, Hart RG, Conway DSG. ABC of antithrombotic therapy: antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation. BMJ 2002;325:1022–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buckingham TA, Hatala R. Anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation: why is the treatment rate so low? Clin Cardiol 2002;25:447–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cromheeke ME, Levi M, Colly LP, et al. Oral anticoagulation self-management and management by specialist anticoagulation clinic: a randomised cross-over comparison. Lancet 2000;356:97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahlra L, Yu G, Perez I, et al. Prospective cohort study to determine if trial efficacy of anticoagulation for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation translates into clinical effectiveness. BMJ 2000;320:1236–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzmaurice DA, Murray ET, Gee KM, et al. Does the Birmingham model of oral anticoagulation management in primary care work outside trial conditions? Br J Gen Pract 2001;51:828–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson SJA, Wells PS, Kovacs MJ, et al. Comparing the quality of oral anticoagulation clinics and by family physicians: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 2003;169:293–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart S, Murphy N, Walker A, et al. Cost of an emerging epidemic: an economic analysis of atrial fibrillation in the UK. Heart 2004;90:286–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang TJ, Massaro JM, Levy D, et al. A risk score for predicting stroke or death in individuals with new-onset atrial fibrillation in the community: the Framingham heart study. JAMA 2003;290:1049–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hutten BA, Prins MH, Redekop WK, et al. Comparison of three methods to assess therapeutic quality control of treatment with vitamin K antagonists. Thromb Haemost 1999;82:1260–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]