Abstract

This report illustrates a magnetic resonance image of aborted myocardial infarction after primary angioplasty. Myocardial oedema in the absence of late enhancement seems to be the magnetic resonance marker of the myocardium at risk of infarction that has been reperfused within 30 minutes and aborted in the clinic.

Keywords: myocardial infarction, aborted myocardial infarction, angioplasty, magnetic resonance imaging, myocardial oedema

A 71 year old man with previous inferior myocardial infarction (MI) was referred to our university hospital because of non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome.

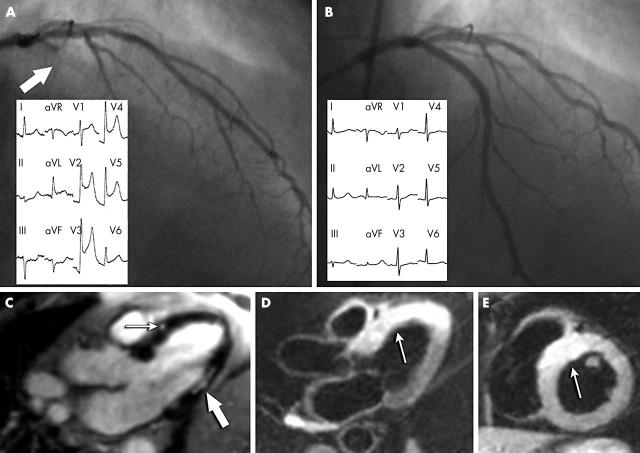

He was treated with aspirin, tirofiban, and nitrates and underwent coronary angiography 24 hours later. The angiography showed a moderate stenosis of the dominant right coronary artery and a severe stenosis of the proximal left descending artery. This last lesion was successfully treated by stent implantation after an oral load of 600 mg clopidogrel. One hour later, the patient had recurrence of angina with ST segment elevation. Immediate coronary angiography showed acute intrastent thrombosis (fig 1A). A new angioplasty was performed 30 minutes after the onset of symptoms with prompt restoration of TIMI (thrombolysis in myocardial infarction) flow grade 3, relief of angina, and ST segment resolution (fig 1B). Peak creatine kinase (CK) was 230 UI/l (upper normal limit 190 UI/l) and troponin I was 7 μg/l. Three days later, cardiovascular magnetic resonance (Harmony, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) (fig 1C) accurately detected an area of late enhancement in inferolateral wall compatible with the old MI. Only minimal hyperenhancement (“necrosette”) was detectable in the mid-segment of the anterior septum. In this region, however, T2 weighted images detected a significant ischaemia related myocardial oedema (fig 1D, E), without evidence of wall motion abnormalities (see video footage—supplemental file posted online).

Figure 1.

Coronary angiographies (main pictures) and 12 lead ECG (windows) (A) showing acute intrastent thrombosis of the left descending artery (arrow) and (B) after percutaneous coronary intervention. (C) magnetic resonance imaging three days after the acute event in long axis view shows an area of late enhancement in the inferolateral wall compatible with the old myocardial infarction (thick arrow) and a spot of minimal hyperenhancement (“necrosette”) in the mid-segment of the anterior septum (thin arrow). A significant area of oedema is visible in T2 weighted images in the (D) long axis and (E) short axis.

DISCUSSION

The expression “aborted infarction” was first used to describe patients treated very early in the MITI (myocardial infarction triage and intervention) trial and who had no evidence of MI after the treatment.1 Lamfers et al2 further characterised the population of patients with aborted MI in a study of 475 patients with suspected ST elevation MI treated with pre-hospitalisation thrombolysis. In this study, a rise in cardiac enzymes (CK, CK MB isoenzyme, aspartate aminotransferase) of less than twice the upper reference concentration was used as the biochemical marker threshold for aborted MI in patients with more than 50% ST deviation resolution within two hours after the treatment. In the ASSENT-3 (assessment of the safety of a new thrombolytic 3) study, the definition of aborted MI considered only the CK peak and evolutionary changes in both the QRS complex and the ST segment.3 Thus, there is no standardised definition of aborted acute MI based on ECG and enzymatic measurements. To the best of our knowledge, our report is the first to provide a magnetic resonance image of a clinically aborted MI because of early reperfusion by primary angioplasty. Myocardial oedema in the absence of late enhancement seems to be the magnetic resonance marker of the myocardium at risk of infarction4 that has been reperfused within 30 minutes and aborted in the clinic. Moreover, as described by others,5 myocardial oedema may persist during the first week, probably because of the intracellular sodium accumulation without loss of integrity of myocardial cells. The discrete region of hyperenhancement (necrosette) close to the implanted stent likely is due, in the absence of minor side branch occlusion, to microvascular obstruction by distal embolisation of plaque material6 after mechanical manipulation during percutaneous coronary intervention. We cannot rule out, however, that it is related in part to the non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome episode because magnetic resonance was not performed between the two ischaemic episodes.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

ASSENT-3, assessment of the safety of a new thrombolytic 3

CK, creatine kinase

MI, myocardial infarction

MITI, myocardial infarction triage and intervention

TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction

None of the authors has financial associations or other involvements that may pose a conflict of interest in connection with the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weaver WD, Cerqueira M, Hallstrom AP, et al. Prehospital-initiated vs hospital-initiated thrombolytic therapy: the myocardial infarction triage and intervention trial. JAMA 1993;270:1211–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamfers EJP, Hooghoudt THE, Hertzberger DP, et al. Abortion of acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction after reperfusion: incidence, patients’ characteristics and prognosis. Heart 2003;89:496–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taher T, Fu Y, Wagner GS, et al. Aborted myocardial infarction in patients with ST-segment elevation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shultz-Menger J, Gross M, Messroghli D, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance of acute myocardial infarction at a very early stage. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:513–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nilsson JC, Nielsen G, Groenning BA, et al. Sustained postinfarction myocardial edema in humans visualized by magnetic resonance imaging. Heart 2001;85:639–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramondo A, Tarantini G, Napodano M, et al. Relationship between pattern of slow reflow and tissue level of perfusion after coronary stenting: a single patient report. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2004;61:221–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.