Patent foramen ovale (PFO) is a common finding in the healthy population, with a prevalence of 27% in one necropsy study of 965 normal hearts from patients with no history of cardioembolic events.1 It is also the most common cardiac finding in young patients (< 55 years of age) with an unexplained cerebrovascular event, presumably caused by paradoxical emboli.2 The presumed mechanism is the migration of a thrombus (or less commonly air or fat) from the venous system to the left atrium via a PFO, with subsequent systemic embolisation. Determining whether paradoxical embolism has occurred through a PFO ideally requires the presence of the PFO “triad”, which combines raised right atrial pressure, venous source of thrombosis, and the presence of PFO. The larger size of a PFO and greater number of microbubbles passing through a shunt during echocardiography has also been associated with an increased incidence of cerebrovascular events3,4

WHEN TO DIAGNOSE A PFO

Although PFO is becoming increasingly recognised as a cause for cryptogenic cerebrovascular events, there are other situations in which documenting a right to left shunt is important. The presence of a large PFO has been associated with severe unexplained decompression sickness caused by paradoxical gas embolism.5 Torti and colleagues showed in 250 scuba divers that the presence of a PFO was related to a low absolute risk of suffering five major decompression illness (DCI) events per 10 000 dives, the odds of which were five times as high as in divers without PFO.6 In addition they showed that the risk of suffering a major DCI parallels PFO size. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations are frequently a manifestation of hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia.7 The presence of PFO has also been associated with persistent hypoxaemia in patients with elevated right heart pressures of various causes.8

HOW TO DIAGNOSE A PFO

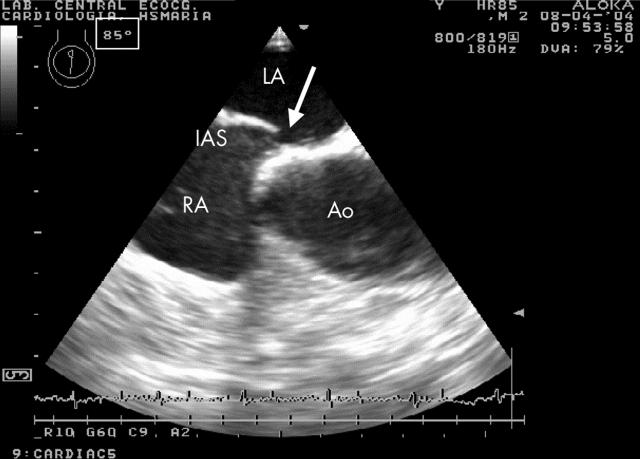

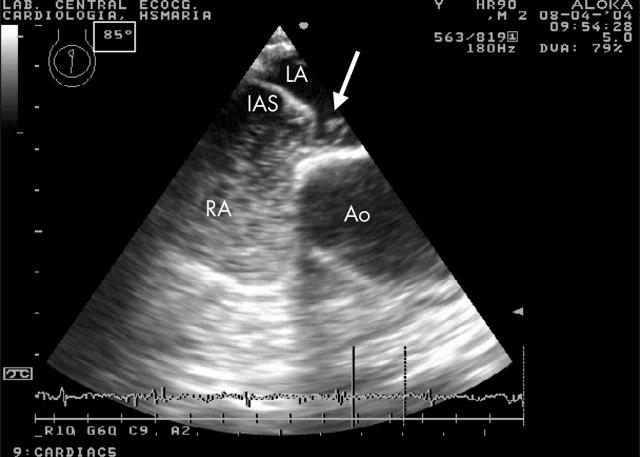

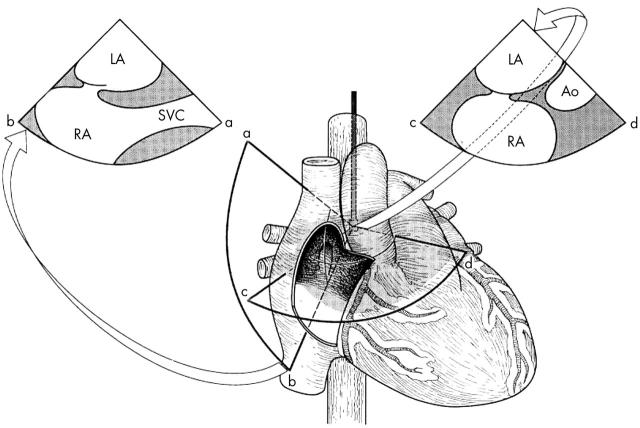

Transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) is superior to transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) for the diagnosis of a PFO and delineation of its morphologic details (figs 1 and 2). Hence, TOE is regarded as the imaging procedure of choice in adult patients with suspected paradoxical embolism.9–11 For the detection of right-to-left shunting across a PFO, agitated saline contrast medium is typically injected into a peripheral vein during the strain phase of the Valsalva manoeuvre and the atrial septum is imaged during the release phase of this manoeuvre. The best angle for visualisation is around 90° corresponding to a more vertical plane. This is most likely due to the PFO orientation, which has a higher probability to affect the more cranial portion of the fossa ovalis where the lack of fusion of the septum primum and the septum secundum is expected11 (fig 3).

Figure 1.

Transoesophageal echocardiography of a patient with a patent foramen ovale (PFO), obtained at 85°, showing a wide separation in the inter-atrial septum (arrow). Ao, aortic root; IAS, inter-atrial septum; LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium.

Figure 2.

The same patient during release of Valsalva and with injected agitated saline, showing the presence of several bubbles across the inter-atrial septum (IAS) into the left atrium (arrow).

Figure 3.

Schematic drawing demonstrating the anatomy of the interatrial septum and the potential superiority of using a more vertical plane (sector image to the left). See text for details. Ao, aorta; LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium; SVC, superior vena cava. Adapted from Chenzbraun et al. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1993;6:417.

Although TOE is considered to be the “gold standard” technique for the diagnosis of right-to-left shunts, the use of sedation makes the performance of the Valsalva manoeuvre more difficult. Kuhl and colleagues12 looked at 111 patients with a cerebral event using a polygelatin contrast agent rather than agitated saline. In this selected group of patients the TTE was performed immediately following the TOE and hence the patient was still sedated, which may have limited their ability to perform a satisfactory Valsalva manoeuvre. Despite this they showed similar positive TTE and TOE for PFOs. Camp and colleagues13 studied 109 consecutive patients and detected 24 patients (22%) with a shunt by both TTE and TOE. Again in this study the TOE was performed first which potentially could result in an unsatisfactory Valsalva manoeuvre. Ha and colleagues14 in their study of 136 consecutive stroke patients detected 40 patients with PFO. They found the sensitivity and specificity of TTE with harmonic imaging to be 62.5% and 100%, respectively, when compared to TOE as the “gold standard”, with no TTE positive/TOE negative patients. More recently Clarke and colleagues15 have shown in a group of 110 patients that TTE with Valsalva manoeuvre was as good as TOE in diagnosing shunts, concluding that Valsalva manoeuvre increases the size of the shunt.15

There is also a need for standardisation of PFO identification and quantification, which at present does not exist. In the French PFO-ASA study, a PFO was defined to be present if at least three contrast bubbles appeared in the left atrium. The degree of shunting was defined to be small if 3–9 contrast bubbles appeared, it was moderate if 10–30 contrast bubbles appeared, and large if more than 30 contrast bubbles appeared in the left atrium.16 In this study sonographers disagreed on the presence of PFO in 13.9% of patients and on the degree of shunting in 26.6%.17 In the patent foramen ovale in cryptogenic stroke study (PICSS) a PFO was considered to be present if > 1 contrast bubble appeared in the left atrium, and the authors used a cut off point for a large shunt if more than 10 bubbles could be demonstrated in the left atrium.18 Very recently it was nicely shown that for a given PFO, the amount of right-to-left contrast shunting is a matter of expiratory pressure during the Valsalva manoeuvre.19 Previously, it was shown that in any PFO right-to-left shunting varies considerably and that the magnitude of contrast shunting does not necessarily correlate with the true anatomical size of the PFO.20–22 Because of the orientation of the inferior vena cava blood (which potentially contains an embolus arising from pelvic or deep vein thrombi) to the fossa ovalis, even a large PFO may be missed if contrast agent is administered through a cubital vein, as these bubbles may be redirected from the fossa ovalis by this blood flow.20,23 These flow patterns are aggravated by a Eustachian valve which directs the blood from the inferior vena cava preferentially to the area of the fossa ovalis and can be studied by contrast administration into the foot vein.21,23,24 As a note, the Eustachian valve is frequently seen in patients with PFO.24,25 Moreover, there are reports showing that transthoracic contrast echocardiography with harmonic imaging mode may be too sensitive at the expense of a decreased specificity for PFO detection.26 Furthermore, the time to appearance of contrast bubbles in the left atrium, which is used as one of the distinguishing features between intracardiac and (physiological) intrapulmonary shunts, has shown to be unreliable.27–30

Transcranial Doppler is an alternative method for detecting a PFO and is considered by some to be superior to the use of two dimensional echocardiographic imaging of the atrial septum after intravenous injection of saline contrast medium.31

CONCLUSION

PFO became an important clinical condition to rule out in certain settings, particularly in young patients with cryptogenic stroke, although not confined only to this condition. The use of echocardiography, particularly of TOE with saline contrast, has been of paramount importance in the diagnosis of PFO. It is, however, important to understand the anatomy and physiology of the interatrial septum and related flow, as well as the potential limitations related with the use of this technique, in order that the likelihood of error is significantly reduced.

Abbreviations

DCI, decompression illness

PFO, patent foramen ovale, TOE, transoesophageal echocardiography

TTE, transthoracic echocardiography

REFERENCES

- 1.Hagen PT, Scholz DG, Edwards WD. Incidence and size of patent foramen ovale during the first 10 decades of life: an autopsy study of 965 normal hearts. Mayo Clin Proc 1984;59:17–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lechat P, Mas JL, Lascault G, et al. Prevalence of patent foramen ovale in patients with stroke. N Engl J Med 1988;318:1148–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Homma S, Di Tullio MR, Sacco RL, et al. Characteristics of patent foramen ovale associated with cryptogenic stroke. A biplane transesophageal echocardiographic study. Stroke 1994;25:582–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stone DA, Godard J, Corretti MC, et al. Patent foramen ovale: association between the degree of shunt by contrast transesophageal echocardiography and the risk of future ischemic neurologic events. Am Heart J 1996;131:158–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Germonpre P, Dendale P, Unger P, et al. Patent foramen ovale and decompression sickness in sports divers. J Appl Physiol 1998;84:1622–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torti SR, Billinger M, Schwerzmann M, et al. Risk of decompression illness among 230 divers in relation to the presence and size of patent foramen ovale. Eur Heart J 2004;25:1014–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barzilai B, Waggoner AD, Spessert C, et al. Two-dimensional contrast echocardiography in the detection and follow-up of congenital pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. Am J Cardiol 1991;68:1507–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Movsowitz C, Podolski LA, Meyerowitz CB, et al. Patent foramen ovale: a non-functional embryological remnant or a potential cause of significant pathology? J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1992;5:259–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pearson AC, Labovitz AJ, Tatineni S, et al. Superiority of transesophageal echocardiography in detecting cardiac source of embolism in patients with cerebral ischemia of uncertain etiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991;17:66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee RJ, Bartzokis T, Yeoh TK, et al. Enhanced detection of intracardiac sources of cerebral emboli by transesophageal echocardiography. Stroke 1991;22:734–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chenzbraun A, Pinto FJ, Schnittger I. Biplane transesophageal echocardiography in the diagnosis of patent foramen ovale. J Am Soc Ecgocardiogr 1993;6:417–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuhl HP, Hoffmann R, Merx MW, et al. Transthoracic echocardiography using second harmonic imaging: diagnostic alternative to transesophageal echocardiography for the detection of atrial right to left shunt in patients with cerebral embolic events. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;34:1823–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Camp G, Franken P, Melis P, et al. Comparison of transthoracic echocardiography with second harmonic imaging with transesophageal echocardiography in the detection of right to left shunts. Am J Cardiol 2000;86:1284–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ha JW, Shin MS, Kang S, et al. Enhanced detection of right-to-left shunt through patent foramen ovale by transthoracic contrast echocardiography using harmonic imaging. Am J Cardiol 2001;87:669–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clarke NRA, Timperley J, Kelion AD, et al. Transthoracic echocardiography using second harmonic imaging with Valsalva manoueuvre for the detection of right to left shunts. Eur J Echocardiogr 2004;5:176–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mas JL, Arquizan C, Lamy C, et al. Recurrent cerebrovascular events associated with patent foramen ovale, atrial septal aneurysm, or both. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1740–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Homma S, Sacco RL, Di Tullio M, et al. Effect of medical treatment in stroke patients with patent foramen ovale. Circulation 2002;105:2625–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cabanes L, Coste J, Derumeaux G, et al. Interobserver and intraobserver variability in detection of patent foramen ovale and atrial septal aneurysm with transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2002;15:441–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devuyst G, Piechowski-Jozwiak B, Karapanayiotides T, et al. Controlled contrast transcranial Doppler and arterial blood gas analysis to quantify shunt through patent foramen ovale. Stroke 2004;35:859–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schuchlenz HW, Weihs W, Horner S, et al. The association between the diameter of a patent foramen ovale and the risk of embolic cerebrovascular events. Am J Med 2000;109:456–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuchlenz HW, Weihs W, Beitzke A, et al. Transesophageal echocardiography for quantifying size of patent foramen ovale in patients with cryptogenic cerebrovascular events. Stroke 2002;33:293–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agmon Y, Khandheria BK, Meissner I, et al. Comparison of frequency of patent foramen ovale by transesophageal echocardiography in patients with cerebral ischemic events versus in subjects in the general population. Am J Cardiol 2001;88:330–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gin KG, Huckell VF, Pollick C. Femoral vein delivery of contrast medium enhances transthoracic echocardiographic detection of patent foramen ovale. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993;22:1994–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schuchlenz HW, Saurer G, Weihs W, et al. Persisting eustachian valve in adults: relation to patent foramen ovale and cerebrovascular events. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2004;17:231–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Homma S, Sacco RL, Di Tullio M, et al. Atrial anatomy in non-cardioembolic stroke patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1066–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madala D, Zaroff JG, Hourigan L, et al. Harmonic imaging improves sensitivity at the expense of specificity in the detection of patent foramen ovale. Echocardiography 2004;21:33–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naqvi TZ, Nagai T, Atar S, et al. Early appearance of echo-contrast simulating an intracardiac shunt in a patient with liver cirrhosis and intrapulmonary shunting. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2002;15:379–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jauss M, Zanette E, for the consensus conference. Detection of right–to-left shunts with ultrasound contrast agent and transcranial doppler sonography. Cerebrovasc Dis 2000;10:490–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nanthakumar K, Graham AT, Robinson TI, et al. Contrast echocardiography for detection of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. Am Heart J 2001;141:243–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed S, Nanda NC, Nekkanti R, et al. Contrast transesophageal echocardiographic detection of a pulmonary arteriovenous malformation draining into left lower pulmonary vein. Echocardiography 2003;20:391–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blersch WK, Draganski BM, Holmer SR, et al. Transcranial duplex sonography in the detection of patent foramen ovale. Radiology 2002;225:693–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]