Abstract

Primary cardiac tumours are quite rare and most of these tumours are benign. In this report, a patient presented with heart failure symptoms attributable to severe mitral valve stenosis. Echocardiography showed a dense left atrial mass causing functional mitral valve obstruction. The morphological and intraoperative presentation was highly suggestive of a myxoma but histopathological examination found a primary pedunculated cardiac angiosarcoma. The role of two dimensional and transoesophageal echocardiography in the assessment of cardiac masses and tumours is discussed.

Keywords: angiosarcoma, left atrium, transoesophageal echocardiography, Doppler echocardiography, functional mitral stenosis

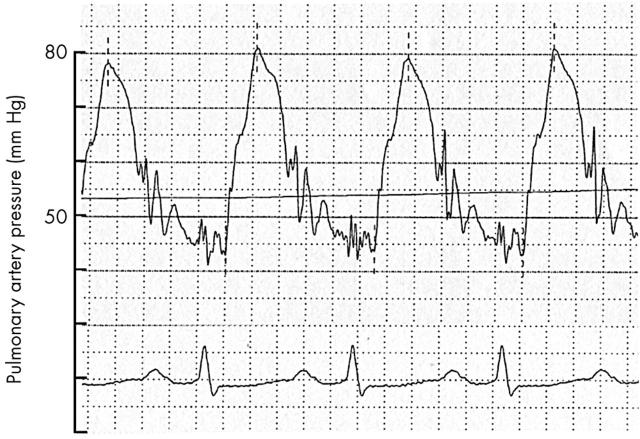

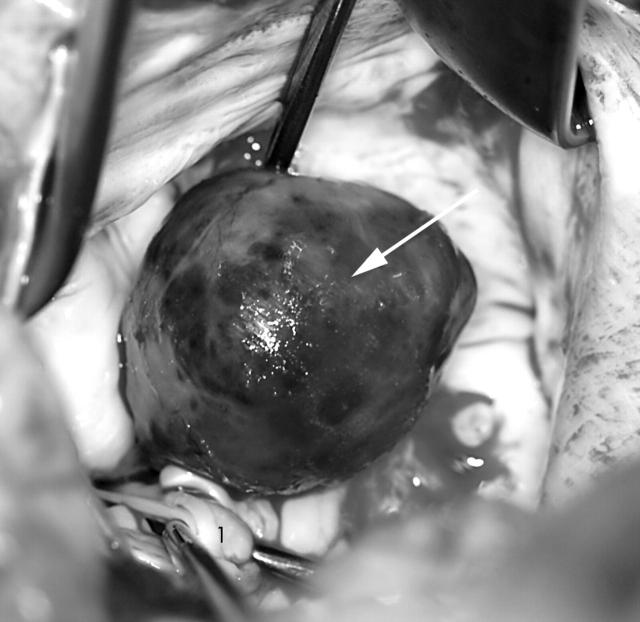

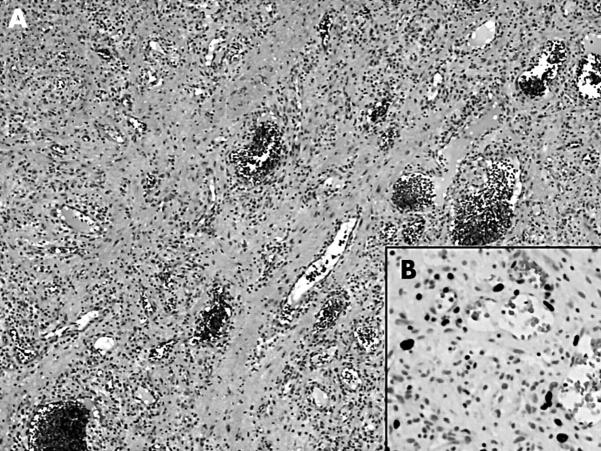

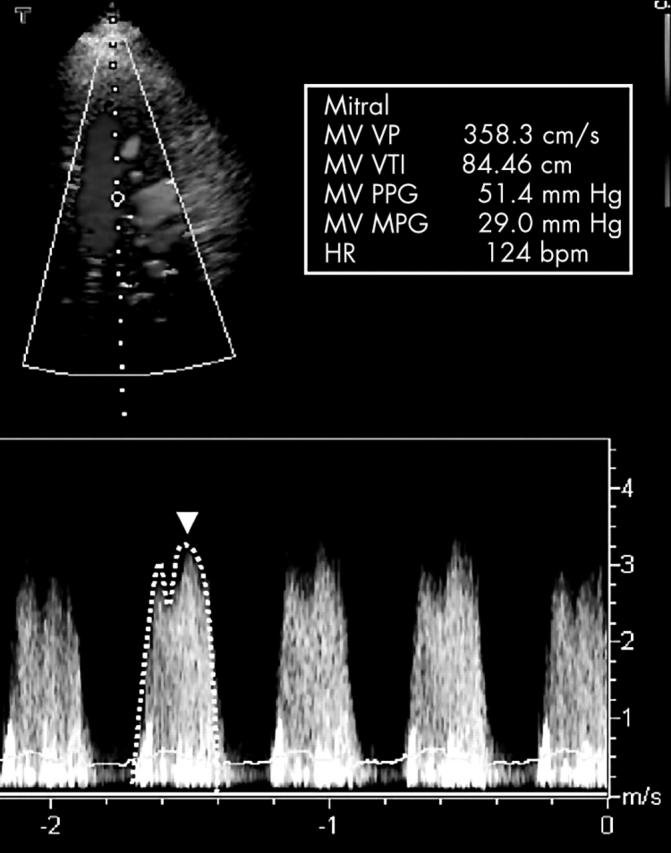

A 63 year old woman was referred to our emergency department with subacute onset of dyspnoea and a 2–3 week history of repeated presyncope and exercise intolerance. Known co-morbidities were chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obstructive sleep apnoea with nasal chronic positive airway pressure treatment at night. No severe cardiovascular diseases were known. On admission, physical examination showed an obese patient (body mass index 31.2 kg/m2) with orthopnoea at rest (New York Heart Association function class IV) and a heart rate of 110 beats/min. Cardiac auscultation showed a diastolic murmur with the maximum point at the fifth intercostal space. Bipulmonary basal rales were present. The ECG showed sinus tachycardia of 110 beats/min with an intermediate heart axis and a slightly broadened bimodal P wave. A transoesophageal echocardiogram showed good systolic function (ejection fraction 70%) and an echo dense homogeneous left atrial mass (21.2 × 18.2 mm) originating from the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve (fig 1). During each diastole, the mass protruded into the left ventricular inflow causing severe functional mitral stenosis. Subsequent transthoracic echocardiography showed turbulent flow across the mitral valve and a mean gradient of 29 mm Hg (fig 2) consistent with severe functional obstruction. From continuous Doppler recordings of the tricuspid valve, a systolic pulmonary artery pressure of 80 mm Hg was estimated. During cardiac catheterisation, relevant stenoses of the epicardial coronary arteries were ruled out. Severe pulmonary hypertension was confirmed with a pulmonary artery pressure of about 80 mm Hg (fig 3). From the morphological aspect, the left atrial mass was highly suggestive of a cardiac myxoma. The patient was scheduled for surgery. During the operation, the tumour was excised through a sternotomy from a transseptal approach (fig 4). Histopathological and immunohistological examinations surprisingly found a highly differentiated angiosarcoma with strong cytoplasmic expression of vimentin of the tumour cells and of factor 8 and CD 34 at the lacunas surrounding the tumour cells (fig 5). No extracardiac manifestations of the tumour were detected. After recovery from surgery, the patient was scheduled for combined chemotherapy and radiation but she preferred to continue the treatment in a hospital close to her home.

Figure 1.

Transoesophageal echocardiogram in the mid oesophageal long axis view with the image plane oriented at 120°. Note an echo dense tumour (TM) in the left atrium (LA) originating from the anterior mitral leaflet protruding into the left ventricular (LV) inflow tract. AO, aorta; RV, right ventricle.

Figure 2.

Transthoracic echocardiogram continuous wave Doppler across the mitral valve (MV) with a peak velocity (VP) of 3.58 m/s and a mean diastolic gradient (MPG) of 29 mm Hg between the LA and the LV. The valve area was not calculated according to the pressure half time method because of the high heart rate (HR) and poor definition of the diastolic deceleration slope in the Doppler pressure tracing. bpm, beats/min; PPG, peak pressure gradient; VTI, velocity time integral.

Figure 3.

Pulmonary artery pressure recording during right heart catheterisation. Note a peak systolic pulmonary artery pressure of nearly 80 mm Hg and a mean pulmonary artery pressure of 55 mm Hg (solid line).

Figure 4.

Intraoperative situs with view through the intra-atrial septum (transseptal access). The arrow marks the roughly 2 cm large tumour originating at the segments A3/P3 of the MV. (1) marks the cordae tendineae of the anterior leaflet of the MV.

Figure 5.

(A) Haematoxylin and eosin stain (5×) displaying a tumour consisting of irregular neoplastic vascular channels surrounded by atypical spindle shaped and epitheloid tumour cells. (B) Immunohistochemical staining (Mib-1) showing moderate mitotic activity of the tumour cells (100×).

DISCUSSION

Primary tumours of the heart are rare. Necropsy studies show incidences between 0.0017–0.28%.1 Most tumours are benign myxomas, which often arise in the left atrium and which are often pedunculated.2,3 Only 10–20% of all primary cardiac tumours are malignant.4,5 The most common histological type of the malignant tumour is angiosarcoma. However, until 1995 fewer than 200 cases had been reported in the English language literature.6 Angiosarcomas almost always originate in the right atrium and are associated with dyspnoea, thoracic pain, general fatigue, or symptoms of right heart failure. However, cardiac tamponade and haemopericardium have also been reported.4 The prognosis of cardiac angiosarcomas is in general poor, ranging from a 6–12 month survival after the diagnosis has been established.7 In the past, most cardiac angiosarcomas were diagnosed at postmortem examination. Modern echocardiography and high resolution tomographic imaging (computed tomography, magnetic resonance tomography) have improved the diagnostic capabilities, facilitating an earlier diagnosis, which may result in an improved prognosis of cardiac angiosarcomas.

The patient described in this case report had a rare left atrial pedunculated angiosarcoma, which has been described only once in the literature.8 However, we are the first to describe a severe functional mitral valve obstruction caused by a cardiac angiosarcoma. In this case, echocardiography was extremely helpful in describing the morphology, size, and origin of the cardiac mass (fig 1). However, echocardiography also provided unique and relevant functional information: detection of a severe gradient across the mitral valve (fig 2) attributable to severe functional obstruction. These findings are in agreement with previous reports, which highlighted the importance of transthoracic and transoesophageal echocardiography in the assessment of cardiac masses.9 Survival time after radical surgery of malignant cardiac tumours can be improved significantly provided that the tumour is diagnosed early.10 In addition, in the case of cardiac tumours echocardiography provides relevant information during serial follow up in that it allows for accurate monitoring after surgery or during radiation therapy or chemotherapy.9

In conclusion, the present case underlines that heart failure symptoms attributable to mitral valve stenosis may also be caused by a cardiac tumour, namely a primary cardiac angiosarcoma. This tumour, which led to a functional valve obstruction, was readily detected by echocardiography. However, histopathological examination is mandatory for the correct diagnosis and initiation of adequate treatment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Griffiths GC. A review of primary tumors of the heart. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 1965;27:465–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rettmar K, Stierle U, Sheikhzadeh A, et al. Primary angiosarcoma of the heart: report of a case and review of the literature. Jpn Heart J 1993;34:667–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorlie D, Myhre ES, Stalsberg H. Angiosarcoma of the heart: unusual presentation and survival after treatment. Br Heart J 1984;51:94–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loffler H, Grille W. Classification of malignant cardiac tumors with respect to oncological treatment. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1990;38 (suppl 2) :173–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwesinger G, Meyer B, von Suchodoletz H. [Incidence of primary heart tumours]. Z Gesamte Inn Med 1984;39:368–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makhoul N, Bode FR. Angiosarcoma of the heart: review of the literature and report of two cases that illustrate the broad spectrum of the disease. Can J Cardiol 1995;11:423–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vander Salm TJ. Unusual primary tumors of the heart. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000;12:89–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ormerod OJ, Spratt PM, Lewis NP, et al. Primary angiosarcoma of the heart mimicking a left atrial myxoma. Thorax 1984;39:798–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheitlin MD, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, et al. ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline update for the clinical application of echocardiography: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASE committee to update the 1997 guidelines for the clinical application of echocardiography). Circulation 2003;108:1146–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmeier A, Deiters S, Schmidt C, et al. Radical resection of cardiac sarcoma. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2004;52:77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]