Abstract

Both hereditary and environmental factors contribute to inter-individual variability in drug response. The considerable interest in the role of genes has to be balanced with the contribution of external influences. Warfarin provides a useful case study of the need to integrate both genetic and non-genetic information when selecting the right dose for a patient. This article discusses the latest data on genotype and warfarin sensitivity and the efforts to incorporate this information into normograms. Exploring the genetics of warfarin response will lead not only to safer prescribing but elucidate the mechanism of action of warfarin and enable the development of new anticoagulant drugs.

Keywords: genetic susceptibility, pharmacogenetics, warfarin

Pharmacogenetics—the use of genetic information to inform the prescribing of drugs—has caught the imagination of clinicians, scientists, and patients alike. It promises greater precision in prescribing, where treatment is tailored to the individual, improving the chances of therapeutic response and reducing the risk of harm. While this is highly desirable, it is important not to lose sight of the fact that environment and behaviour also influence the effect of a drug. At best, genotype will be only one of a number of factors that need to be considered when prescribing for a patient. Warfarin provides a good illustration of the complex interplay between genes and environment in determining patient response and the practical issues in delivering on personalised medicines.

Warfarin is currently the most widely used oral anticoagulant in the world.1 Individual response to the drug is highly variable. In a given population, prescribed doses can vary from 1–40 mg or more daily. Importantly, the therapeutic index in any one patient is very narrow. Patients are monitored closely using the international normalised ratio (INR) for prothrombin time but this adds expense and the incidence of bleeding complications, estimated at 7.6 to 16.5 per 100 patient years, remains high. The period of highest risk of bleeding complications is around the start of warfarin treatment.2,3 In an ideal setting, the physician would like to predict the dose required for each patient without the need for trial and error.

WARFARIN SENSITIVITY

As any medical student will recall, many clinical and behavioural factors influence the response to warfarin and need to be considered when prescribing the drug. These include diet, alcohol intake, body mass, concomitant drug treatment, co-existing disease, and patient compliance. Genes are also important. The first gene affecting warfarin sensitivity to be identified was CYP2C9. This gene encodes the enzyme (CYP2C9) responsible for metabolising the pharmacologically more potent S-enantiomer of warfarin to inactive metabolites.4 A least six single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of CYP2C9 have been found which may influence enzyme activity.5 Studies show that the 2C9*2 and 2C9*3 variants have 12% and 5% of the enzyme activity of the wild-type allele, 2C9*1,6,7 and that patients with these variant alleles require significantly lower doses of warfarin than patients with the wild-type gene, with evidence of a gene–dose effect (such that homozygotes are more sensitive than heterozygotes).8,9,10,11 These variants are associated with a significantly increased risk of bleeding during induction of anticoagulation with warfarin,12,13 but not during maintenance.9

WARFARIN RESISTANCE

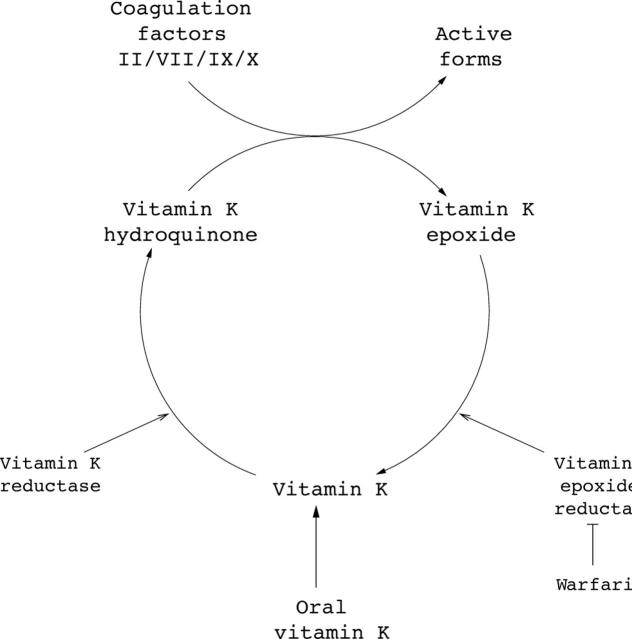

At the other end of the spectrum, inherited resistance to warfarin is well recognised in rats, mice, and humans.14 Warfarin acts by inhibiting the enzyme vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR). This enzyme recycles vitamin K epoxide to reduced vitamin K (fig 1). The latter is oxidised back to vitamin K epoxide in a coupled reaction that causes carboxylation and activation of the coagulation factors II, VII, IX, and X (the so called “vitamin K dependent clotting factors” which make up the intrinsic coagulation pathway). Until this year, little was known about VKOR as it had been only partially purified and its gene had not been identified. In an elegant series of experiments using family linkage studies and rodent genetics, two groups have identified a gene (termed vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1 or VCORC1) with a central role in determining VKOR activity.15,16 VKOR was thought to be a large multicomplex protein, but expressing the product of VKORC1 alone bestowed VKOR activity in insect cells that did not have it while targeted inhibition of VCORC1 expression with small interfering RNAs notably reduced VKOR activity. Thus, this molecule alone may be responsible for recycling vitamin K. Missense mutations in this gene appear to explain inherited warfarin resistance in humans and rats.15,16

Figure 1.

Cyclical reduction and oxidation of vitamin K is inhibited by warfarin. Dietary vitamin K is reduced to vitamin K hydroquinone by vitamin K reductase. Vitamin K hydroquinone is then oxidised to vitamin K epoxide in a coupled reaction which results in the activation of coagulation factors II, VII, IX, and X. Vitamin K epoxide is then reduced back to vitamin K by vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR). This enzyme is inhibited by warfarin, leading to a block in the cycle, which results in a depletion in activated clotting factors.

IMPLICATIONS FOR WARFARIN PRESCRIBING

How might this genetic information influence our use of warfarin? In general terms, the value of genotyping a patient for a given variant depends upon the frequency of the allele, the mode of effect (autosomal dominant/recessive), the size of the gene effect, and cost.17 Inactivating CYP2C9 alleles are not uncommon, being found in 35% of the white population.9,11,18 At least three studies have explored the contribution of genotype alone and together with demographic and clinical factors to determining the maintenance dose of warfarin.10,11,19 In univariate analyses, CYP2C9 genotype alone appears to account for between 10–20% of the variability in maintenance dose of warfarin. Taking genotype along with factors such as age, body surface area, sex, and concomitant drug use, explained between 29–39% of the variability in warfarin dose. Gage and colleagues10 have devised a normogram, using genotype and other factors available at the time of starting treatment with warfarin, to estimate warfarin requirements before commencing treatment and argue that its use would reduce the risk of bleeding around the time of initiating anticoagulation with the drug. They concede that it would not eliminate the need for INR monitoring and recognise that use of the normogram needs to be evaluated for cost effectiveness in a prospective study.

Conversely, heredity resistance to warfarin is rare. Whether there are common polymorphisms of VKORC1 with significant effects on warfarin sensitivity in the general population is now the subject of further study.20 For the present, routine genotyping for VKORC1 variants is not indicated. It would be of diagnostic value when a patient appears to require a particularly high dose of warfarin; the demonstration that the patient had genetically determined resistance would indicate the need for an anticoagulant with a different mode of action.

DEVELOPING BETTER DRUGS

But there is more than one gain from pharmacogenetic studies of this sort. Pharmacology can inform disease genetics and genetic strategies can lead to the development of better drugs. In this case, VKORC1 allelic variants are not only responsible for warfarin resistance but can also give rise to hereditary deficiency of vitamin K dependent clotting factors.15 Meanwhile, clarifying the molecular target for warfarin permits more detailed study of the structure and function of this enzyme and the possibility of new pharmacological inhibitors, ideally with different kinetics and less inter-individual variability.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hirsh J, Fuster V, Ansell J, et al. American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation guide to warfarin therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:1633–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landefeld CS, Beyth RJ. Anticoagulant-related bleeding: clinical epidemiology, prediction, and prevention. Am J Med 1993;95:315–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Douketis JD, Foster GA, Crowther MA, et al. Clinical risk factors and timing of recurrent venous thromboembolism during the initial 3 months of anticoagulant therapy. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:3431–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scordo MG, Pengo V, Spina E, et al. Influence of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms on warfarin maintenance dose and metabolic clearance. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2002;72:702–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gage BF, Eby CS. Pharmacogenetics and anticoagulant therapy. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2003;16:73–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rettie AE, Wienkers LC, Gonzalez FJ, et al. Impaired (S)-warfarin metabolism catalysed by the R144C allelic variant of CYP2C9. Pharmacogenetics 1994;4:39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haining RL, Hunter AP, Veronese ME, et al. Allelic variants of human cytochrome P450 2C9: baculovirus-mediated expression, purification, structural characterization, substrate stereoselectivity, and prochiral selectivity of the wild-type and I359L mutant forms. Arch Biochem Biophys 1996;333:447–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aithal GP, Day CP, Kesteven PJ, et al. Association of polymorphisms in the cytochrome P450 CYP2C9 with warfarin dose requirement and risk of bleeding complications. Lancet 1999;353:717–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taube J, Halsall D, Baglin T. Influence of cytochrome P-450 CYP2C9 polymorphisms on warfarin sensitivity and risk of over-anticoagulation in patients on long-term treatment. Blood 2000;96:1816–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gage BF, Eby C, Milligan PE, et al. Use of pharmacogenetics and clinical factors to predict the maintenance dose of warfarin. Thromb Haemost 2004;91:87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hillman MA, Wilke RA, Caldwell MD, et al. Relative impact of covariates in prescribing warfarin according to CYP2C9 genotype. Pharmacogenetics 2004;14:539–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Margaglione M, Colaizzo D, D’Andrea G, et al. Genetic modulation of oral anticoagulation with warfarin. Thromb Haemost 2000;84:775–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higashi MK, Veenstra DL, Kondo LM, et al. Association between CYP2C9 genetic variants and anticoagulation-related outcomes during warfarin therapy. JAMA 2002;287:1690–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kohn MH, Pelz HJ. A gene-anchored map position of the rat warfarin-resistance locus, Rw, and its orthologs in mice and humans. Blood 2000;96:1996–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rost S, Fregin A, Ivaskevicius V, et al. Mutations in VKORC1 cause warfarin resistance and multiple coagulation factor deficiency type 2. Nature 2004;427:537–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li T, Chang CY, Jin DY, et al. Identification of the gene for vitamin K epoxide reductase. Nature 2004;427:541–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cardon LR, Idury RM, Harris TJ, et al. Testing drug response in the presence of genetic information: sampling issues for clinical trials. Pharmacogenetics 2000;10:503–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scordo MG, Caputi AP, D’Arrigo C, et al. Allele and genotype frequencies of CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 in an Italian population. Pharmacol Res 2004;50:195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wadelius M, Sorlin K, Wallerman O, et al. Warfarin sensitivity related to CYP2C9, CYP3A5, ABCB1 (MDR1) and other factors. Pharmacogenomics J 2004;4:40–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D’Andrea G, D’ambrosio RL, Di Perna P, et al. A polymorphism in VKORC1 gene is associated with an inter-individual variability in the dose-anticoagulant effect of warfarin. Blood 2004; epub (9 September). [DOI] [PubMed]